Abstract

According to Health Canada (2016), only about 11% of older men meet recommended guidelines for physical activity, and participation decreases as men age. This places men at considerable risk of poor health, including an array of chronic diseases. A demographic shift toward a greater population of less healthy older men would substantially challenge an already beleaguered health-care system. One strategy to alter this trajectory might be gender-sensitized community-based physical activity. Therefore, a qualitative study was conducted to enhance understanding of community-dwelling older men’s day-to-day experiences with physical activity. Four men over age 65 participated in a semistructured interview, three walk-along interviews, and a photovoice project. An interpretive descriptive approach to data analysis was used to identify three key themes related to men’s experiences with physical activity: (a) “The things I’ve always done,” (b) “Out and About,” and (c) “You do need the group atmosphere at times.” This research extends the knowledge base around intersections among older men, physical activity, and masculinities. The findings provide a glimpse of the diversity of older men and the need for physical activity programs that are unique to individual preferences and capacities. The findings are not generalized to all men but the learnings from this research may be of value to those who design programs for older men in similar contexts. Future studies might address implementation with a larger sample of older men who reside in a broad range of geographic locations and of different ethnicities.

Keywords: gerontology, development and aging, healthy aging, masculinity, gender issues and sexual orientation, health promotion and disease prevention, health-care issues, qualitative research, research

As the population ages, the number of older people is expected to increase dramatically. During the upcoming decade, there will be an increase of more than 236 million people aged 65 years and older throughout the world (Wan, Goodkind, & Kowal, 2016). In North America, rising life expectancy has been driven in part by advanced medical interventions that are more readily available and accessible. Health-care systems for many years have been organized around hospital care and treatment of acute health conditions. With the aging demographic shift, health care has begun to shift toward community-based primary health-care services to support older adults living independently for as long as possible (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2015). Tantamount to preserving older adults’ independence, there is an urgent need for community-based health promotion programs.

Given physiological and environmental factors that often accompany aging (i.e., loss of muscle mass and bone, functional decline, decreased mobility, changes in physical and social environments) older people are at significant risk of chronic diseases (Daley & Spinks, 2000). Physical activity can mitigate these risks; however, older men and women are the least physically active Canadians, relative to younger age groups, with high rates of inactivity and declining leisure time expenditure with increasing age (Hirsch et al., 2010). This is true for both men and women, although much less research has focused on men

Aging is a complex process with intersecting personal, societal, and environmental factors that include gender, social, and physical environments (Mazzeo et al., 1998). Gender is a “set of socially constructed relationships which are produced and reproduced through people’s actions…[and] there is very high agreement in society about what [actions] are considered to be typically feminine and typically masculine” (Courtenay, 2000, p. 1387); its relation to men’s physical activity is a key, yet understudied factor. Dominant ideals of masculinity are commonly associated with being White, heterosexual, educated, of European descent, and of middle to upper socioeconomic status (Bennet, 2007; Courtenay, 2000; Verdonk, Seesing, & de Rijk, 2010). Dominance and control along with characteristics of self-reliance, strength, and stoicism are also key to claims of patriarchal views of accepted performances of “manliness” (Smith, Braunack-Mayer, Wittert, & Warin, 2007). Being emotionally restrained, independent, autonomous, capable, and tough in mind and body are highly valued and requisite to breadwinner and protector roles (Courtney, 2000). These expectations may be powerful drivers of men’s health practices and behaviors, including physical activity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Schippers, 2007). However, there is considerable diversity in how men align with and enact these masculine ideals. For example, men may demonstrate masculine qualities of strength and independence, but how they demonstrate these qualities varies based on age, culture, ethnicity, social class, and sexuality (Courtenay, 2000).

As the preponderance of physical activity research has focused on women, there is relatively little known about older men’s experiences of physical activity (Bredland, Magnus, & Vik, 2015). Masculine ideals are often not considered when designing innovative physical activity programs for older men (Bottorff et al., 2015). Few health promotion studies have contextualized older men’s experiences of physical activity, and even fewer have used qualitative methods beyond traditional interviews (Chaudhury, Mahmood, Michael, Campo, & Hay, 2012; Lockett, Willis, & Edwards, 2005; Shumway-Cook et al., 2002; Van Cauwenberg et al., 2012).

The purpose of this study was to shed light upon contexts that influence older men’s involvement in physical activity.1 Specifically, the following question was addressed: How can older men’s day-to-day experiences with physical activity inform the development of targeted physical activity programs?

Methods

An interpretive descriptive approach was used (Thorne, 2016), comprised of photovoice methods, individual interviews, and participant observations using walk-along interviews. From these, themes were distilled across older men’s day-to-day experiences that might inform development of targeted physical activity programs.

Recruitment and Sample

In accordance with University of British Columbia ethics approval, H14-03317, a convenience sample of four community-dwelling older men was recruited for this current study. These men had previously participated in an interview study about physical activity and indicated their willingness to be contacted for further research. Inclusion criteria were broad: they had to self-identify as men age 65 or older; be able to communicate in English; live in the community; and, be able to move about within and outside their homes.

The four participants, ages 70–86, were White, of European background, functionally capable of completing daily activities and chores, and satisfied with their financial status. Within this small sample, there was considerable diversity in their personal and health experiences and social situations (Table 1). Each participant was given a pseudonym to protect their privacy that will be used throughout this research.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics.

| Age | Highest level of education | Marital/social status | Living situation | Health status | Ability to perform activities of daily living | Driver’s license | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Participant #1

Pseudonym: Carl |

86 | University Degree | Widowed | Alone; independent living | Multiple chronic health conditions | Assistance with meals and housekeeping from an outside hired source. | Yes; owns a car |

|

Participant #2

Pseudonym: Craig |

70 | Graduate Degree | Divorced; self-identified as gay | Alone; apartment | Generally healthy; history of back pain and some shortness of breath | Independent in all tasks | Yes; access to car |

|

Participant #3

Pseudonym: Leonard |

78 | Secondary School | Married | Home; single family home with wife | Previous stroke; mild cognitive decline | Assistance with meals, transportation, and housekeeping from his wife | No; has support from wife |

|

Participant #4

Pseudonym: Lee |

80 | Secondary School | Single and never married | Alone; owns his home | Generally healthy; history of leg pain following biking accident as a pedestrian | Independent in all tasks; no walking aids | Yes; owns a car |

Data Collection

Data were gathered through semistructured interviews, walk-along interviews (as a form of participant observation), and photovoice methods. The use of multiple data collection methods provided in-depth and contextual data that reflected participants’ complex experiences with physical activity (Phinney, Dahlke, & Purves, 2013). Questions of an open nature in the semistructured interviews encouraged depth and vitality through the collection of rich data (Doody & Noonan, 2013); through walk-along interviews, researchers were able to gain additional insight through participant observation (Butler & Derrett, 2014); and, photovoice methods allowed researchers to gain insights into participants’ perceptions of their physical activity (Wang & Burris, 1997). Verbal and written consent were obtained prior to beginning data collection. Two trained research assistants facilitated each session and documented their observations in field notes after the sessions.

Each semistructured interview, which took between 21 and 68 min, was audio-recorded and transcribed. Participants were asked about their daily routines and activities, factors that motivated or got in the way of them getting out in their communities, transportation, their most and least favorite ways of being physically active, satisfaction with their physical activity levels, and their thoughts around gender differences in physical activity and aging.

Participants took part in three walk-along interviews, ranging from 30 min to 1 hr, and these were video-taped and/or audio-recorded., allowing for the examination of participants’ experiences, interpretations, and practices as they moved about and engaged in their everyday environments (Carpiano, 2009). These included how the physical environment influenced physical activity, physical function and abilities, safety aspects, and social settings and social interaction. Participants chose activities that they typically engaged in, both inside and outside their home, while describing their experiences and thoughts in the context of this activity. Locations and activities for walk-along interviews included walks around the neighborhood, dog-walking, trips to the grocery store, running errands such as going to the bank or library, conducting house tours, yard work and indoor household chores, and accompanying a participant to a community Senior’s Center.

Participants took photographs to illustrate how elements of the physical and social environment influenced their mobility and physical activity. Instructions were left intentionally broad to allow participants the freedom to take photographs they felt were relevant. These photographs were subsequently used to discuss specific aspects of physical activity in individual interviews which were audio-recorded and transcribed. Permission for use of these photos in this research was obtained through ethics and informed consent of the research participants. The final data set across the four participants included field notes from 20 sessions, 10.17 hr of audio-recorded data, 2.17 hr of video-recorded data, and 54 photographs. As an honorarium, participants received a $10 CAD gift card for a supermarket or coffee shop for each of the 5 sessions they participated in.

Data Analysis

These data were analyzed for themes following principles of interpretive description, in which the main premise is to generate knowledge that can be applied to practice (Thorne, 2016). Data analysis therefore stayed focused on the research question, taking into consideration both what participants stated about their involvement in physical activity programs as well as interpretations around how the men’s experiences can help inform development of targeted physical activity programs. An interpretation framework was developed to guide preliminary analysis for each participant. The framework was laid out as a series of questions. For example: What are his usual physical activities? What does physical activity mean to him? What barriers does he experience? This framework provided a deductive structure for extracting and organizing data in such a way to assure the answering the overall research question. At the same time, it was a useful inductive tool to examine the data from each participant in depth, interpret, and ultimately classify and compare data across the participants, while looking for meaningful commonalities and distinctions in their experiences of physical activity. From this, overarching themes that best portrayed key patterns and meanings within the data and their interconnections were developed.

Findings

The sample of four men provided diversity in their range of experiences, as well as depth in the data generated. Three themes emerged, reflecting commonalities across participants: (a) “The things I’ve always done,” (b) “Out and About,” and (c) “You do need the group atmosphere at times.”

“The Things I’ve Always Done”

Participants tended to reflect on times when they were younger and how their life circumstances and physical health had changed, and how it continued to change with age. It was evident that participants’ past experiences with physical activity resonated with them and significantly influenced the activities they currently engaged in. For example, Carl had spent a significant amount of his life playing tennis. He had multiple chronic health conditions including: bilateral knee replacements, a history of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), prostate cancer, a previous surgery for colon cancer, glaucoma, hypertension, back pain, unbalanced gait, as well as a fall that cracked his pelvic bone. After multiple hospitalizations, the nature of Carl’s physical activity significantly changed and although he had been managing most of his diagnoses, perhaps his biggest challenge was his loss of balance and stability. Ultimately, the participant had to give up tennis, a sport he had participated in for 70 years.

“I was getting bit wobbly on my legs especially with the titanium knees…I hated having to give up tennis, but I didn’t want to fall and break something if I got dizzy or unbalanced on the court.”—Carl

Through his multiple health transitions, the participant continued to go back to the tennis club to visit and socialize with his friends. He shared that he went “down there about half a dozen times a week,” demonstrating the importance of the tennis club to his weekly activities and a routine he had been following for decades.

Leonard provided another example of how the past can significantly contribute to current patterns of physical activity. This participant was generally healthy until he suffered from a stroke about a year prior to his interview. Since then he had some short-term memory loss, loss of peripheral vision, and some cognitive impairment. Aside from the cognitive impairment, Leonard was able to almost fully recover from his stroke in terms of regaining strength and balance. His motivation for recovery was inspiring in that he was able to resume almost all his pre-stroke activities. He spent a great deal of time at his local seniors’ recreation center, in which he participated in multiple activities several times a week. Leonard appeared to be motivated by being able to do the activities he had always done in the past, possibly reflecting the importance of strength and resilience to this participant. When asked what motivated him to recover from his stroke, he said,

“I don’t know where that comes from, but I guess just the things I’ve always done, you know.”—Leonard

This statement reflected meaning, purpose, and adhering to routines that the participant had become accustomed to, allowing him to continue being as physically active as possible given his circumstances and reflecting masculine ideals of ability and strength.

Additionally, Courtenay (2000) and Donaldson (1993) have argued that as men age it is likely that they will become more conservative and perhaps dependent on others for certain tasks and activities; however, a desire to be self-reliant in completing routine activities may be meaningful to the men in positioning themselves as strong, independent, and capable men. Their decisions to continue doing what they have always done may be perceived as “risky” due to the physical changes associated with aging, but these tasks are also a part of who these men are. For example, as part of his daily walks, Leonard took his dog down a steep creek located nearby his home, shown in Figure 1. The participant’s willingness to engage in this activity might be argued as risky. However, there was also something about completing this task that was meaningful to him, perhaps representing ideals of routine, purpose, and doing, or the masculine virtue of providing for another—his dog.

Figure 1.

Leonard going for a walk with his dog in his neighborhood. He captioned this photo “I took this picture because… It’s what we try to do daily and it was a beautiful day; the dog needs exercise too.”

As another example, Lee lived independently in a home he had owned for about 30 years. He engaged in various chores around the house including gardening, landscaping, painting, cleaning gutters, and other minor repairs. In doing these tasks, he carried all of his supplies from his backyard to his front yard; the supplies were quite large and heavy, and his stairs were steep with no railings (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The stairs the participant used to carry his yard tools to the front yard.

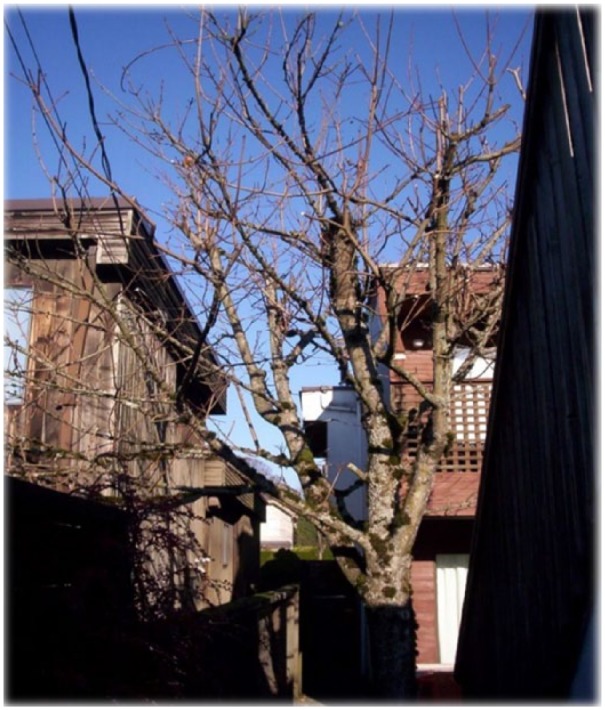

Further, this participant also trimmed the branches of a tree in his backyard using a 16-foot ladder (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The tree that the participant climbs on a 16-foot ladder to trim.

“Okay, I’m on the 16-foot ladder at the top. The ladder’s propped against the tree. I’m right up at the top of a ladder using a hedge clipper to trim the tree. As long as I’m careful, you know, no problem.”—Lee

This task seemed to give Lee a sense of accomplishment and independence in remaining capable of an activity that he had probably engaged in all his life:

“Things can happen, but so far I’ve been able to do it and I feel it’s positive for my overall mental health… It means that I’m not completely out of it yet, given [my] age.”—Lee

This participant’s actions are perhaps more overtly risky, in that an element of performativity in both the doing, and the sharing of the story with others, may offer assurances of independence and manly risk taking.

As a final example, Carl continued to drive regularly to complete his daily tasks and chores. This 86-year-old man had significant health challenges that impaired his ability to drive safely, specifically a history of TIAs and vision problems. However, this man relied heavily on his car, Figure 4, for transportation.

Figure 4.

The picture taken by Carl of his car. Losing his license would be a very significant transition for this participant due to his heavy reliance on his car.

He explained,

“I’d be lost without my car. Because I’m, you know, I don’t think I’d be very good getting on a bus, on and off a bus, especially if I’ve got any shopping or something like that. Yeah, I’d be terribly lost without a car. I’d have to be taking taxis.”—Carl

Behaviors are often framed as actions that older men should or should not partake in for their well-being. However, for the men in this study, it was about balancing rights, risks, and responsibilities. From a societal point of view, their actions may be considered a safety risk, but the men may have also been seeking to maintain familiar routines and activities at a time when they were experiencing multiple losses to prevent losing a part of themselves. Remaining physically and functionally able with advancing age is a key contributor to quality of life, and specifically for men, this quality may reflect masculine values of independence, self-reliance, strength, and control. The photographs shared here tended to reflect factors that supported the participants’ independence, reiterating the importance of this ideal.

“Out and About”

Aspects of the environment exerted a direct effect on physical activity, which was especially important to consider for those who use walking for transportation. Getting out and about in their communities was a key component of physical activity for these men, as they engaged in a fair amount of walking and moving around in the context of their day-to-day lives. The men discussed the importance of the physical environment in motivating their levels of physical activity, as well as the convenience of amenities and facilities in contributing to their daily routines and activities.

For Craig and Lee, walking was the most common method of transportation. A key factor in these two participants’ high frequency of walking was the convenience of their neighborhoods. Both men had nearby access to amenities and facilities; grocery shops, banks, the library, public transportation, as well as restaurants, coffee shops, parks, and multiple other facilities were within walking distance. Both participants felt that the city of Vancouver was very easy to get around in, “especially with the convenient locations of shops and easily accessible transit” as stated by Craig. Interestingly, this participant stated that because he lived in Vancouver, he did not face any significant barriers to getting around his community, but felt that if he had lived in a more suburban community, he might have seen more challenges.

“I don’t want to sound sort of overly praising of Vancouver, but I really think Vancouver, at least at my level of mobility which is not really impaired, not majorly– I don’t have a major impairment. So at this level I find getting around town, particularly living here, is so easy…say we were in, well, I don’t know almost anywhere other than downtown Vancouver, say we were in Surrey or in, I don’t know, well, a small community in the Interior. There might be things that I would find difficult.”—Craig

Craig’s input around the convenience of his residence in Vancouver demonstrated the importance of the physical environment, and the proximity of amenities, to mobility and physical activity. His recent choice to move to a location central to amenities and public transportation may reflect the importance of independence, functional capability, and being able to walk to accomplish daily tasks and chores.

On the other hand, Carl and Leonard both relied on driving as their main form of transportation, either by driving themselves, or being driven by a significant other, and thus walked more so for leisure. Although these men lived in urban and suburban areas, amenities such as grocery stores and public transportation were fairly long distances to walk. These men also faced greater health issues relative to the other two men, thus making walking long distances more challenging. These examples demonstrated the need to consider intersections between the environment, physical activity, and health situations for men as they continue to age.

In addition to the proximity of amenities and facilities, the participants discussed how aesthetics of and safety in the physical environment influenced their comfort and ability to walk outside. The three participants residing in the large suburban city discussed how much they enjoyed the beautiful views during their walks, specifically the mountains, the water, and the greenery.

“You can see why I go down there because it’s– you’re right on the sea and there’s a beach there.”—Carl

The following two photographs, Figures 5 and 6, were taken by Craig and Lee respectively. Both of these participants resided adjacent to beautiful parks and beaches, further motivating them to walk to where they needed to go.

Figure 5.

The photo taken by Craig depicting the aesthetics of the neighborhood while enjoying a meal; he captioned “Beautiful weather and miles of water and safe bicycle paths are a strong encouragement to get out and enjoy some exercise.”

Figure 6.

The photo taken by Lee, showing the view from his house; he explained how this view encourages him to go for a walk.

“Vancouver has made my mobility more, you know, inviting, more easy.”—Craig

Further, the participants were generally not bothered by the rain; Craig stated,

“I belong to a group called Out and About…as long as it’s not pouring with rain, we’ll go somewhere.”

Although comments around aesthetics were generally positive and participants expressed satisfaction with their neighborhoods, the participants lived in areas that could be quite busy with heavy traffic from vehicles, pedestrians, or bicycles, making safety concerns worthy of consideration. For example, Leonard discussed on multiple occasions how bike lanes were unsafe because they are often used as right turn lanes; he photographed the image below (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The picture taken by Leonard; he believed the bike lanes were hazardous because people used them as right turn lanes, causing cyclists to use the sidewalk, creating safety risks for pedestrians. He stated, “Well, briefly, you should be able to ride a bicycle on the bicycle path, and I would actually ride a bicycle if I thought it was safe for anybody. Not just for me, but for anybody to go around on the bicycle. But they use the car—cars use that bicycle path for a right turn lane. And with the kids going to school there, it’s just awful. And you say—I mean, it’s very dangerous, but nobody’s had an accident there, so they won’t do anything.”

Lee had an incident in which he, as a pedestrian, was struck by a cyclist. Since then, he experienced ongoing leg pain, negatively impacting the frequency and intensity of the activities he was able to engage in. Furthermore, the incident left the participant traumatized, as he expressed that he avoided certain areas of his neighborhood. Although these two men had unfortunate experiences with cycling and bike paths, Craig discussed the positive aspects of his neighborhood around the safety of bicycle paths. This participant cycled for leisure and discussed how his city was a positive and safe motivating factor in him being physically active. Figure 8 were taken by Craig reflecting bicycle safety.

Figure 8.

Photographs taken by Craig during (A) walks and (B) cycling.

The four participants generally enjoyed the neighborhoods they lived in and felt comfortable walking outside. The proximity of amenities, the aesthetics, and the familiarity of the communities provided facilitating factors for the participants’ physical activity, whereas high-density neighborhoods and high-traffic areas may have posed challenges and barriers.

“You Do Need the Group Atmosphere at Times”

Personal experiences and social environments significantly influenced participants’ physical activity. For example, level of community involvement, extent to which help was needed, and social interaction were all factors influenced by the participants’ social situations and subsequently influenced physical activity levels.

Being involved in the community can significantly influence older men’s level of engagement with others. It can help motivate physical activity by promoting socialization, and it can give people a sense of connection and belonging to a group of people with similar interests. For example, Carl retained strong connections with a tennis club and its members, a club he was part of for 44 years. Although he was no longer physically capable of playing tennis, he still visited the tennis club several times a week to watch others play, to have a meal, or have a beer with friends. The tennis club was a significant part of Carl’s physical and social life that he continued to identify himself with; it is probable that this tennis club provided a sense of comfort and routine for him, as well as a source of motivation to get out in his community to continue to be involved.

“Yeah, if a man can keep in a club of some sort it’s good, because, you know, he sees people of his own age who have also semi-retired from tennis. And you can watch tennis and there’s people swimming in the pool so– going into the sea. And you can watch the yachts on the water and what’s going on and admire the view. And so I think my club has helped me a tremendous lot because there is somewhere to go. If men can stay active or, you know, go to their– kind of social club of some sort, whether it’s a golf club or whatever, it’s– they do last longer. I think they kind of give up.”—Carl

Carl’s continued involvement with his tennis club perhaps provides linkages to the masculine values of competitive sport and social class, which he had carried across his life course. Tennis and tennis clubs in this participant’s area of residence can be quite expensive, and these interconnections likely denote him as well-resourced. Thus, White middle-class masculine ideals may be reflected in this participant’s advocacy for community and sports-club involvement.

Leonard maintained strong connections with his community, specifically in the form of a Seniors Recreation Center, where his main activity was carpet bowling. The social interaction aspect of the game was a significant component of the participant’s motivation to continue to attend the sessions. The members of the recreation center formed a close-knit group; during the game, members were very supportive of one another, while at the same time engaging in some friendly competition. Leonard was an advocate for community involvement; similar to Carl’s feelings around his tennis club, he stated the following about seniors’ centers:

“You definitely need to join a senior centre. And once you get to a certain age, I think it’s very accommodating and it keeps you going.”—Carl

In contrast to Carl’s tennis clubs, resources such as community centers are typically less expensive and are often subsidized. These findings reflect the importance of intersections between social class, community involvement, and physical activity patterns.

Craig was quite involved with his community; however, the specific activities he was involved in were due to the various challenges he described since “coming out” to his friends and family, leading to him getting divorced, losing communication with his son, and having to change his social circle and activities. He shared that he used to do quite a bit of boating and sailing but stopped since having to find a new group of friends; since then, he became involved in walking and hiking groups and built new social connections. Craig was involved with both the “Health Initiative for Men Program” which involved warm up exercises and light activity with other gay men, as well as “Out and About,” which was a gay men’s hiking group. The marginality of gay men within masculine hierarchies may have limited with whom and how this participant could socially connect in advancing age. This participant also had a history of depression; it was clear that his community involvement was especially important in promoting social interaction and for him, maintaining mental and emotional health while preventing further episodes of depression.

“Oh, I am subject to periods of depression all my life and I’ve learned that activity’s a good antidote. So I try to get out every day as– partly as therapeutic.”—Craig

Lee was not quite as involved with the community and activity groups as the other men; however, he did make an effort. When asked what motivates him to get out into his community, he shared:

“My physical health and certainly emotional health to a degree as well. The fact that you have done something or completed a job gives you a degree of satisfaction.”—Lee

This participant’s motivation was rooted in a combination of knowing that physical activity would improve his mental and emotional health, as well as it being good for him physically. Unfortunately, his incident of being struck by a cyclist resulted in ongoing leg and knee issues, causing him to give up his hiking group, and the social connections associated with it. He wished he could have continued hiking but shared that he became too slow and could not keep up with the others in the group; he shared that he first signed up for this hiking group for the social interaction.

An important commonality present in each of the men’s community-based activities was socialization. However, despite discussing the importance of this factor, three of the men also associated women with being more social as they age.

“I think women seem to, from what I’ve seen anyway, keep a social network going, and enlarge it even as they get older. And I think for many men, they see their social network diminishing as people die or—become ill, that sort of thing.”—Craig

Carl and Lee expressed similar opinions in that they referred to men as loners, and believed women were more socially active and more likely to have stronger and wider social networks as they aged.

Maintaining social networks and increased social interaction has commonly been reported as a feminine attribute, whereas independence, self-reliance, and solitary activities have been associated with masculine qualities and ideals (Charles & Carstensen, 2010; Courtenay, 2000; Smith et al., 2007). Although in some cases this may be true, there is some evidence in this research illustrating that there may be disconnects between what is expected of men by society as they age, and what is actually happening. For example, three of the men maintained social connections within their communities as they aged: Carl with the tennis club; Leonard with the Senior’s Center; and, especially Craig who maintained and even built new social networks after his divorce. Lee referred to himself as a “loner” but also shared that he is only “vaguely happy” with his social life. Perhaps the men are implying that it is “more difficult” for men to do this work of social connection, in that it does not come as naturally as it does for women. This positioning may also reflect a perceived ease and effortless that femininities afford, but a purposeful manly endeavor for men.

Discussions around programs also revealed that one of the key facilitators in joining a physical activity program was around social interaction, but within smaller groups rather than larger groups. Craig shared that he did not have much motivation for solo exercise with his statement “self-motivation for solo exercise other than walking is—it’s not there.” That said, an important consideration around physical activity programs is what is realistic and accessible for the participants, possibly implying that activity alone at home may be the easiest in certain circumstances. For example, Leonard expressed some concern about transportation, as he believed this would be his biggest challenge. He discussed how although he supported the group atmosphere, he would choose to do physical activities at home to not overburden his wife in driving him. His concerns demonstrate the need to consider factors such as accessibility, convenience, and social support networks when promoting participation in programs for older men.

“Well, you do need the group atmosphere at times, that’s for sure. But I like doing my exercise at home, rather than going to a gym. For I mean two or three reasons: the cost and also the time to get there and get back” … “Without a car, you just don’t dare to open your mouth and say oh, I’m going to do this or do that very often. So I don’t participate in that type of—it puts too much pressure on my wife.”—Leonard

The men appeared to share discourses around the blend of solitude and social connectedness, positioning them as independent and not entirely reliant on social connections—but at the same time recognizing the benefits of connecting with others.

Discussion

Findings from this research allowed for the interpretation of men’s everyday activities and the gauging of what constitutes and contributes to older men’s physical activity. Participants were motivated to be physically active because it allowed them to independently accomplish daily tasks, and supported their physical and mental health and well-being. Physical activity also provided a sense of continuity; important routines and practices were evident in the participants’ current patterns of physical activity. A sense of satisfaction, purpose and comfort may stem from participants’ physical capacity to participate in activities they know and enjoy. Being out and about in their communities was a significant part of these men’s experiences with physical activity. Their physical activity was facilitated by neighborhood aesthetics, residential proximity to amenities, and their familiarity with the neighborhood. Highly populated neighborhoods and high traffic areas posed potential challenges to their physical activity and safety. Social environments and connections proved to be of utmost importance in men’s day-to-day lives. Continued involvement in their communities and maintaining strong connections with community groups such as seniors’ recreation centers, tennis clubs, and walking and hiking groups provided a sense of belonging and purpose. Although the men discussed being socially interactive as a feminine quality, it remained important to each participant in a different way. From the results, three suggestions are offered to inform development of targeted, community-based physical activity programs.

Focus on Programs That Meet the Unique Needs of Older Men

Older men are at risk of inactivity and functional decline as they age (Chaudhury et al., 2012); thus, participation in physical activity is essential for healthy aging. Societal expectations around gender may generate the belief that men are self-reliant and competently able to handle their own health. The participants appeared to welcome participation in programs that they believed would benefit their social–emotional and physical health. While the specific findings varied from one man to another, overall it appeared as though increased social interaction, strength-building, and regaining balance were the main facilitators for the participants joining physical activity programs, specifically for the men who were living with chronic conditions Most importantly, participants believed that as they aged, these factors would support their independence and capacity to engage in preferred activities. Thus, it is essential to consider the unique needs of older men when designing programs to build the strength and capacity needed for them to be independent enough to engage in their communities and to grow old in their own homes. One example of a successful community program is called Men’s Sheds. These peer-run community groups allow men to gather in safe and friendly environments, have been designed to prevent isolation, loneliness, and depression in retired men, enhance community involvement, and improve mental and physical health (Canadian Men’s Sheds Association [CMSA], 2017).

Consider the Influence of Men’s Physical and Social Environments

Participants spontaneously identified factors such as weather, quality and safety of sidewalks and crossings, and neighborhood density as important. Thus, programs should include outdoor components with these factors in mind. Program facilities need to be aesthetically appealing and accessible in safe and familiar neighborhoods. These same factors enhanced physical activity and motivation to get out in the community in previous reports (Van Cauwenberg et al., 2012).

Walking was the primary mode of transportation for the participants and in previous studies (Lockett et al., 2005; Van Cauwenberg et al., 2012). As transportation can be a major barrier to program participation and accessibility to facilities, older adults should be informed about transportation services as well as programs available to them in their communities (e.g., reduced transit fares and shared ride services). Although financial constrains often limit older adults’ access to programs (Rasinaho, Hirvensalo, Leinonen, Lintunen, & Rantanen, 2007), this was not of concern to the participants. Subsidized or low-cost programs led by volunteers may serve to eliminate this barrier.

Group-based activities enhance sense of belonging, enjoyment, and establish friendships; this in turn, provides motivation to continue engaging with physical activity (Franco et al., 2015). Although two men were happy as “loners,” there were different opinions about exercise group size versus solitary exercise in which all participants expressed some interest in social interaction as part of physical activity programs. Most effective programs for men reported previously were those that included regularly scheduled group activity, and individualized exercise plans supervised by personal trainers (Bottorff et al., 2015). The diverse views from this small sample suggest that mixed modes of program delivery promote program adherence and satisfaction.

For men, physical activities such as walking for travel, completing daily tasks, or recreating within one’s neighborhood is often part of daily life (Chaudhury et al., 2012). Health promotion programs for older men that also catalyze friendships may support relationship building within communities and engage men in group physical activity and daily tasks. Franco et al. (2015) discussed the value of social contact and familiar faces when performing physical activities. Social connection can be incorporated into programs by engaging participants in social events, fundraisers, through volunteer events and pub nights, and by connecting via email or newsletters (Effervescent Bubble, 2016).

Finally, research findings enhanced awareness of how men may think and feel about social interaction. Although the participants feminized social aspects of aging, they valued maintaining social connections as they aged. The men associated women with being more social as they age, but they themselves also maintained, and in some cases, even built new social networks as they aged. This finding reflects an apparent disconnect between what men say and what men do. Although they may hold traditional societal beliefs around gender-based social behavior, their personal behaviors may represent a more complex reality.

Use a Participatory Approach That Is (a) Strength-Based and Focused on What Older Men Are Physically Capable of Doing, and (b) Gender-Sensitized and Activity-Based

Effectiveness of interventions depends on intersections between gender, age, social and physical environments, and individual factors, among others (Bottorff et al., 2015). Yet, relatively few physical activity programs consider both age and gender in their design. Masculine values surfaced in the participants’ day-to-day activities, how they thought about aging, types of physical activities they engaged in, and their underlying motivation to be active. In their own unique ways, these men valued specific masculine traits which demonstrate the intersections between gender and aging (Smith et al., 2007). Thus, there is a need to consider these connections when designing targeted physical activity programs for older men.

Programs tailored to specific populations or groups were highly successful and accomplished what they were designed to do (Bottorff et al., 2015). Older men should be invited to actively participate in physical activity program planning such as contributing to a meaningful discussion around what types of activities, and goals, might motivate participants to join a program; these goals can then be met in the design of the program. The participants suggested a rich variety of activities they enjoy, and how these activities might be incorporated into a physical activity program. Activities included: strength training, walking, swimming, boating, dancing, lawn bowling, table tennis, and hiking. This reflects the importance of “choice” in program design, as each participant may have a personal preference as to what is meaningful to them, and what they are capable of doing given their health status and experience with chronic conditions. Successful programs might use a strength-based approach to focus on each person’s physical capacity, and an activity-based approach to offer activities that provide men purpose, enjoyment, and meaning.

Men’s past experiences with physical activity demonstrated the importance of routine and meaning. This, as well as previous, research (Franco et al., 2015) identified that maintaining habits was a significant motivational factor for physical activity in older adults. Successful programs for older men have been reported to incorporate activities that give men purpose throughout their lives such as building projects and tools. For example, the CMSA encourages men to socialize and engage in common interests such as woodworking projects, cooking, bike repairs, music, and watching sports (CMSA, 2017). Programs such as these connect the importance of routine, purpose, and social connectedness, while considering the influence of masculinities on aging men.

It is recognized that limitations of this study include using a small sample size of White, urban-dwelling (Vancouver, BC), generally healthy, physically functional, educated, and financially comfortable older men to examine physical activity.

Conclusion

The myriad health benefits of physical activity are well-known. However, factors associated with engaging older men in physical activity are poorly understood. Factors such as gender, age, the influence of physical and social environments, and health status all play a role and should be incorporated into a tailored (for population) design of health promotion interventions. Due to the limitation of a small, relatively homogenous, sample size, findings are not generalized to all men, however they may be of great value to older men in similar contexts. Future studies might address implementation with a larger sample of older men who reside in a broader range of geographic locations, and of different ethnicities. Although this research provides a glimpse, there remains a need to address the range of complex factors that compel older men to engage in physical activity.

In this research, “physical activity” reflects the World Health Organization’s (2016) definition for older adults, in which physical activity is considered in the context of daily family and community activities and includes: leisure activities (e.g., walking, dancing, gardening, hiking, swimming); transportation (e.g., walking, cycling); occupational, if the individual is still engaged in work; household chores; games; and sports or planned exercise.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Ref. Number 138295). Writing up of this work was partly funded by Movember Canada (Grant #11R18455).

References

- Bennett K. M. (2007). “No sissy stuff”: Towards a theory of masculinity and emotional expression in older widowed men. Journal of Aging Studies, 21(4), 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff J. L., Seaton C. L., Johnson S. T., Caperchione C. M., Oliffe J. L., More K., … Tillotson S. M. (2015). An updated review of interventions that include promotion of physical activity for adult men. Sports Medicine, 45(6), 775–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredland E. L., Magnus E., Vik K. (2015). Physical activity patterns in older men. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Geriatrics, 33(1), 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. (2015). Primary and community care in BC: A strategic policy framework. Retrieved February, 2018, from https://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2015_a/primary-and-community-care-policy-paper-exec.pdf

- Butler M., Derrett S. (2014). The walking interview: An ethnographic approach to understanding disability. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 12(3), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Men’s Sheds Association. (2017). Men’s Sheds: Getting things done, together. Retrieved December, 2017, from http://menssheds.ca/

- Carpiano R. M. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The “go-along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place, 15(1), 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S. T., Carstensen L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury H., Mahmood A., Michael Y. L., Campo M., Hay K. (2012). The influence of neighborhood residential density, physical and social environments on older adults’ physical activity: An exploratory study in two metropolitan areas. Journal of Aging Studies, 26(1), 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M. J., Spinks W. L. (2000). Exercise, mobility and aging. Sports Medicine, 29(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson M. (1993). What is hegemonic masculinity? Theory and Society, 22(5), 643–657. [Google Scholar]

- Effervescent Bubble. (2016). Fit fellas. Retrieved September, 2017, from https://effervescentbubble.ca/2016/07/21/fit-fellas/

- Doody O., Noonan M. (2013). Preparing and conducting interviews to collect data. Nurse Researcher, 20(5), 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M. R., Tong A., Howard K., Sherrington C., Ferreira P. H., Pinto R. Z., Ferreira M. L. (2015). Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(19), 1268–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. (2016). Health aging: Physical activity and older adults. Retrieved November, 2016, from http://publications.gc.ca/Collection/H39-612-2002-4E.pdf

- Hirsch C. H., Diehr P., Newman A. B., Gerrior S. A., Pratt C., Lebowitz M. D., Jackson S. A. (2010). Physical activity and years of healthy life in older adults: Results from the cardiovascular health study. Journal of Aging and Physical activity, 18(3), 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockett D., Willis A., Edwards N. (2005). Through seniors’ eyes: An exploratory qualitative study to identify environmental barriers to and facilitators of walking. CJNR (Canadian Journal of Nursing Research), 37(3), 48–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo R. S., Cavanagh P., Evans W. J., Fiatarone M., Hagberg J., McAuley E., Startzell J. (1998). Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 30(6), 992–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney A., Dahlke S., Purves B. (2013). Shifting patterns of everyday activity in early dementia experiences of men and their families. Journal of Family Nursing, 19(3), 348–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasinaho M., Hirvensalo M., Leinonen R., Lintunen T., Rantanen T. (2007). Motives for and barriers to physical activity among older adults with mobility limitations. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 15(1), 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schippers M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook A., Patla A. E., Stewart A., Ferrucci L., Ciol M. A., Guralnik J. M. (2002). Environmental demands associated with community mobility in older adults with and without mobility disabilities. Physical Therapy, 82(7), 670–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A., Braunack-Mayer A., Wittert G., Warin M. (2007). “I’ve been independent for so damn long!”: Independence, masculinity and aging in a help seeking context. Journal of Aging Studies, 21(4), 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2016). Interpretive description, qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Cauwenberg J., Van Holle V., Simons D., Deridder R., Clarys P., Goubert L., … Deforche B. (2012). Environmental factors influencing older adults’ walking for transportation: A study using walk-along interviews. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonk P., Seesing H., de Rijk A. (2010). Doing masculinity, not doing health? A qualitative study among Dutch male employees about health beliefs and workplace physical activity. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H., Goodkind D., Kowal P. (2016). An aging world: 2015 (International Population Reports). Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; Retrieved from https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p95-16-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Burris M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). Physical activity and older adults. Retrieved October, 2016, from http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_olderadults/en/