Abstract

Tailoring psychological treatments to men’s specific needs has been a topic of concern for decades given evidence that many men are reticent to seek professional health care. However, existing literature providing clinical recommendations for engaging men in psychological treatments is diffuse. The aim of this scoping review was to provide a comprehensive summary of recommendations for how to engage men in psychological treatment. Four electronic databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO) were searched for articles published between 2000 and 2017. Titles and abstracts were reviewed; data extracted and synthesized thematically. Of 3,627 citations identified, 46 met the inclusion criteria. Thirty articles (65%) were reviews or commentaries; 23 (50%) provided broad recommendations for working with all men. Findings indicate providing male-appropriate psychological treatment requires clinicians to consider the impact of masculine socialization on their client and themselves, and how gender norms may impact clinical engagement and outcomes. Existing literature also emphasized specific process micro-skills (e.g., self-disclosure, normalizing), language adaption (e.g., male-oriented metaphors) and treatment styles most engaging for men (e.g., collaborative, transparent, action-oriented, goal-focused). Presented are clinical recommendations for how to engage men in psychological treatments including paying attention to tapping the strengths of multiple masculinities coexisting within and across men. Our review suggests more empirically informed tailored interventions are needed, along with formal program evaluations to advance the evidence base.

Keywords: masculinity, gender, psychotherapy, review, help-seeking

Findings consistently indicate that many men are reluctant to seek help for mental health concerns (Seidler, Dawes, Rice, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2016; Sierra Hernandez, Han, Oliffe, & Ogrodniczuk, 2014). Governments and not-for-profit organizations have attempted to counteract this problematic gender trend through design and dissemination of targeted campaigns to increase men’s access to and uptake of mental health services including efforts like “HeadsUpGuys” (Ogrodniczuk, Oliffe, & Beharry, 2018) and “Real Men, Real Depression” (Rochlen, Whilde, & Hoyer, 2005). Such population-based initiatives have been spurred by a belief that awareness will increase service uptake, reducing the profound economic and social burden of psychiatric illness and suicide amongst men (Whiteford et al., 2013). Preliminary evidence suggests male uptake of such services is increasing and men will and do seek help in some circumstances (Fogarty et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2015; Seidler, Rice, Oliffe, Fogarty, & Dhillon, 2017) What remains unclear are the specific factors that facilitate men’s uptake and engagement with psychological treatments.

While psychological treatment has been reported as equally efficacious for men and women (Staczan et al., 2017) recent findings suggest some men have difficulty engaging with specific forms and elements of treatment (Johnson et al., 2012) (e.g., finding it difficult to engage in a trusting therapeutic relationship). Hence, men are often initially ambivalent toward psychological treatment (Good & Robertson, 2010) and drop out of services prematurely (Pederson & Vogel, 2007; Spendelow, 2015). The impact of dropout, and negative treatment experiences risk deferral or avoidance of services in the future (Calear, Batterham, & Christensen, 2014; Syzdek, Green, Lindgren, & Addis, 2016).

In attempting to understand this issue, many explanations have been offered. One long-standing hypothesis critiques restrictive ideals of traditional masculinity (e.g., strength and stoicism) as contradicting the emotional vulnerability and communication needed to access and fully engage with effective psychological treatment (Seidler et al., 2016; Vogel & Heath, 2016; Westwood & Black, 2012). Such “deficit-based” perspectives regarding male socialization have been contested. Notably, with the rise of strength-based approaches to men’s psychological treatment (e.g., Kiselica & Englar-Carlson, 2010) has come a focus on the limitations of services, and clinicians, to treat a diverse male clientele. These limitations include inadequate clinician training in gender socialization (Mellinger & Liu, 2006; Williams & McBain, 2006), clinicians’ biases towards or against masculinity (Owen, Wong, & Rodolfa, 2009), and structural barriers and unappealing service environments (Seidler, Rice, Oliffe, et al., 2017). Thus, the reasons for many men’s mistrust of institutional care and problematic help-seeking behaviors have garnered increasing scholarly attention.

Recommendations for what works when treating men have also been offered. These efforts have sought to overcome perceived structural and procedural disconnects between the mental health field and many men (Galdas, Cheater, & Marshall, 2005). Notably, however, direction from leading organizations in the field for appropriate practices with male clients is largely absent. For example, while the American Psychological Association (APA) has established guidelines for psychologists working with girls and women, ethnic minorities, older adults, and sexually diverse clients (APA, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2007), guidelines for psychologists working with men are still in the drafting stage, despite a long-identified need (e.g., Mahalik, Good, Tager, Levant, & Mackowiak, 2012). Of note, Mahalik and colleagues (2012) developed a taxonomy of useful clinical considerations regarding treatment of boys and men. As a strong starting point, these recommendations, derived from hundreds of working clinicians, require consolidation with the empirical literature following it.

Consequently, the men’s mental health field currently lacks overarching consensus, or even a clear summary, of best practices and key issues to consider when working with men in therapeutic settings.

The number of clinical handbooks and commentaries aimed at addressing male-friendly practices is testament to the clinical interest in this field (e.g., Brooks, 2010; Englar-Carlson, Evans, & Duffey, 2014; Rochlen & Rabinowitz, 2014). These recommendations focus on adapting the clinical environment, therapy content, and therapeutic relationship to be men-centered, taking into account the effects of masculine socialization on many men’s experiences leading up to, and entering, psychological treatment. That is, societal norms that prescribe “how to be a man” through alignment with traits (e.g., independence, risk taking) that in turn interact with health help-seeking processes. Existing recommendations span professional disciplines (e.g., nursing; social work; psychology), treatment settings (e.g., individual therapy; group therapy), methodologies (e.g., case study; pilot trial), presenting problems (e.g., substance overuse; depressive symptoms), and culturally diverse groups (e.g., African American men; Latino men).

However, a synthesis of such recommendations, which could guide clinical practices and inform future research directions, is absent from the literature.

Considering the diversity of resources in the men’s psychological treatment area, the current review focuses on the “how” of psychological treatment with men, over the “what.” That is, how clinicians understand, relate to and communicate with their male clients. The decision to limit to only recommendations made for the therapeutic process rather than technical elements and components of psychological treatments (e.g., motivational interviewing; thought disputation) was taken to ensure the findings of this scoping review were practical and actionable by clinicians, regardless of their treatment orientation. These therapeutic processes have been termed “male-friendly adjustments” to psychological treatment approaches (Englar-Carlson et al., 2014).

In extracting, reviewing, combining, and summarizing these resources, our aim was to provide a comprehensive assessment for clinicians and researchers on recommendations for how to engage men in psychological treatment. The secondary aim of this review was to provide the groundwork for more empirically derived clinical intervention trials of tailored men’s psychological treatment in the future.

Methods

Scoping reviews are useful when a field, typified by complex or heterogeneous research, has yet to be comprehensively reviewed (Mays, Roberts, & Popay, 2001). This style of review literally “scopes” out the size and nature of a broad research question (e.g., what are the recommendations for engaging men in psychological treatment), to report back on the state of the field. They can act as a means to summarize research findings drawn from existing literature to identify knowledge gaps and make recommendations (Armstrong et al., 2011; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010; Rumrill, Fitzgerald & Merchant, 2010). As the clinical literature addressing men’s psychological treatment recommendations is broad, multidisciplinary and methodologically diverse, a systematic review with a full methodological quality analysis was neither appropriate nor feasible. In line with Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework for scoping reviews, five incremental stages were followed in the current scope: (a) identify the research question, (b) search and retrieve studies, (c) select studies, (d) extract and table the study data, and (e) collate and summarize the results. The below outlined methodology of the current scoping review ensured maximum methodological rigor in line with a systematic review.

Identifying the Research Question

The research question developed to guide the review was: What is known from the existing literature about engaging men in the therapeutic process for psychological treatment? For the purpose of this scoping review, therapeutic process refers to variables clinically relevant to the interactions between client and clinician, including the:

attitudes, behaviors, and experiences of men;

attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of clinicians (therapeutic stance);

nature of the dyadic interaction (therapeutic alliance), the environment, and atmosphere in treatment.

Therapeutic process is seen to remain independent of specific treatment models as clinicians work with men across treatment settings and styles (Boterhoven de Haan & Lee, 2014). Therefore, recommendations on “how” to adapt psychological treatment were believed to have the greatest utility for clinicians in the field of men’s mental health because of their generalizability (Richards & Bedi, 2015).

Identifying Relevant Studies

The authors adhered to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA guidelines; Moher, Liberati, Tetziaff, & Altman, 2009; see supplementary file 1). Empirical (qualitative, quantitative, mixed) and review or commentary articles were identified through four electronic databases searched in March 2017 (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PubMed). A search strategy was iteratively devised for use with PsycINFO and adapted for other databases (see supplementary file 2). Both MeSH thesaurus terms and free text words were used. Further manual searching of reference lists from identified articles was undertaken.

Study Selection

Initial search results were merged and duplicates removed following Cochrane Collaboration guidelines (Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2008). Two researchers (ZS, HD) independently screened titles and abstracts excluding articles based on the following stipulated criteria. Studies selected for inclusion in the scoping review met the following criteria: (a) articles published from 2000 onward; (b) both purely male and mixed gender samples; (c) include recommendations for men 16 years and older or broadly addressing “boys and men”; (d) included recommendations provided by either men or clinicians on how to treat or alter psychological treatment when working with men; (e) included recommendations exploring all psychological models of care (e.g., psychodynamic, narrative, CBT); (f) peer-reviewed and published articles with original data or commentary/opinion pieces; (g) English language.

The second stage involved examination of full texts to assess eligibility by three researchers (ZS, HD, SR).

Charting the Data

Data were extracted by one reviewer (ZS) and checked for accuracy by two other reviewers (HD, SR). The extracted data included: author, year and location of study, design, setting, participant characteristics, treatment style and modality, theoretical orientation and key recommendations.

Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

A thematic analysis approach was adopted to synthesize the included articles’ findings due to their heterogeneity (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The synthesis was undertaken using MS excel in distinct stages to identify recurrent and unique themes. First, one researcher (ZS) read all articles, annotated them and identified broad topic categories through free line-by-line coding of their findings. These codes represented common phrases across articles about how to approach certain facets of treatment with male clients. Additional articles read were mapped to previously identified categories, and categories were added as new topics emerged. These free codes were iteratively grouped into relevant areas or “descriptive” themes based on their overall focus (e.g., clinician insight or orienting the client). These themes, based on article recommendations, were not mutually exclusive, and each article mapped to multiple categories. To establish trustworthiness, a second researcher (HD) independently reviewed 20% of included articles and derived their own categories. All discrepancies, disagreements, and unique findings were discussed with a third independent researcher (SR) to reach consensus. This independent, inter-rater process followed standard qualitative analysis methods applied to ensured rigor and to minimize potential for subjective interpretation by a single author. The final stage, development and discussion of clinically oriented “analytical” themes took place with all five authors where wording of clinical recommendations and final grouping were discussed. The wording of the themes in Table 2 were derived from repeated phrases in the relevant articles and clarified amongst all authors using non-jargonisitic language where possible to increase the utility for a broad clinical readership. The number of articles addressing each recommendation was recorded at the outset of free-coding and is reported to ensure rigor and replicability.

Table 2.

Key Themes Based on Clinical Recommendations.

| Being aware of gender socialization: Reflecting on the impact of gender for both clinician and client | • When conceptualizing the client, consider the following: ○ Gender role socialization analysis: ■ Childhood & development, its links with masculine socialization and links with current stressors, traits or values—1, 3, 7, 8, 15, 23, 24, 25, 28, 35 ■ Sexuality issues, values, belief and orientation (e.g., performance, power, porn)—9, 25 ■ Different subcultures of men and how they define masculinity—3, 15, 19, 25, 33, 34, 46 ■ Importance of work life—12, 19 ○ How gender conforming or nonconforming patterns contribute to the presenting symptomology (e.g., externalizing distress)—6, 7, 8, 11, 17, 25, 33, 35, 37 ○ How gender may be contributing to men’s discomfort & shame approaching treatment—4, 6, 9, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 24, 25 ○ The full range of masculinities—6, 10, 12, 41, 42 (including) ■ Masculine strengths (read, understand, explain)—12, 19, 28, 30, 31, 45 ○ Move beyond sex differences to individual differences and intra-individual variability in experience or expression of masculinities—1, 6, 24, 25, 35 ○ Rage, guilt, grief and fear how they may interfere with therapeutic outcomes if not included as a focus of therapy—8, 25, 46 ○ Masculine gender role cognition—1, 6, 7, 26, 41, ○ Masculine gender role conflict—7, 15, 17, 35 ○ Clinician’s own internal gender role stereotypes, assumptions & biases, potential subsequent countertransference and its effects on the client—4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15. 18, 19, 24, 25, 28, 34, 37, 38, 46 ○ Clinician’s own gender and the potential interplay with traditional masculinity (e.g., “fear of the feminine”)—8, 17 |

|

Clarifying structure:

Providing a clearly structured, transparent and goal-oriented intervention |

• Devise, set and check progress on specific goals and develop plan of action collaboratively to increase acceptance—2, 3, 8, 12, 15, 16, 20, 22, 29, 34, 39, 40, 44, ○ Prioritize immediate goals as stepping stones toward long term progress—16, 23, 24, 39 • Offer a clear and transparent structure for sessions (with goals in mind)—11, 13, 17, 20, 24, 29, 32, 39, • Link back with previous sessions as a way to emphasize progress—2, 29, 32, 39, • Avoid general questions, be specific and make suggestions through open-ended questions—2, 5, 11, 15, 16, 33 • Ensure both the clinician and client are clear on broad roadmap of therapy, for example, breakdown of treatment options and components—4, 39, 41 • Plan skills practice, review and feedback each week addressing specific goals—5, 10, 12, 22, 37, 39, • Explore and navigate expectations around treatment regarding:—2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 17,19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, 34, 36, 37, 39 ○ Therapist (role orientation) ○ Client (power dynamic, transparency) ○ Anticipated progress and timeline ○ How and why of therapy (reduce fear of ulterior motives) ○ Accountability for actions ○ Self-management and self-regulation (as outcomes) ○ Parameters of treatment (boundaries) |

|

Building rapport and a collaborative relationship:

Assuming a strength-based approach to building a strong therapeutic alliance |

To employ a strength-based relational style, consider the following: ○ Validate experience; Encourage the client; provide unconditional positive regard; normalize (re. masculinity, depression); be honest—1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 16, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30, 31, 33, 39, 41, 42 ○ Use appropriate self-disclosure—2, 3, 11, 15, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44, 46 ○ Avoid challenging traditional masculine norms, male awkwardness, emotional communicative difficulties early in treatment—1, 6, 11, 18, 19, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 35 41, 45. ○ Accentuate and explore positive aspects of masculinity throughout therapy and use to clinical advantage—6, 8, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 23, 24, 26, 28, 28, 31, 36, 37, 39, 41, 45 ○ Meet male client where he is at, accept rather than expect conformity masculine norms (avoid polarization)—6, 15, 16, 17, 18 ○ Join the client in his predicament and accept misgivings—16, 19, 31 |

| • Ensure the therapeutic relationship is: egalitarian, emotionally supportive, reciprocal, collaborative and nondirective—2, 3, 11, 12, 20, 21, 24, 27, 29, 30, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44, • Emphasize in treatment that:—2, 3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 19, 21, 22, 27, 29, 30, 31, 36, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44, 46 ○ Power, control and decisions are shared, ○ The client brings an expert perspective of his life and is responsible for change, ○ The client’s autonomy is sought, not denied (empowerment is the goal) ○ The client should value his own needs ○ Confidentiality will be respected (in context of duty of care) |

|

|

Tailoring language:

Adapting language and communication style for male clients |

• Use male-oriented language that respects maleness—4, 8, 13, 14, 20, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 36, 40, 41, 43, 44. ○ Use action-oriented vocabulary (e.g., picking up tools). ○ Use alternative labels for therapeutic work (e.g., fix) ○ Use informal language if appropriate (e.g., swearing) ○ Put an emphasis on hard work and moving forward in life • Employ communication that includes appropriate use of: ○ Humor—19, 21, 25, 33, 40, 44, ○ Brief and specific communication—20, 28, 33, 35, 42, 44, ○ Conversational and colloquial dialog—14, 33, 43 ○ Male appropriate metaphors. (e.g., sporting, building)—14, 25, 27, 28, 38, 40 ○ Active use of unspoken nonverbal communication (eye-contact, physicality)—2, 28 |

Note. Numerical items refer to articles listing each recommendation as numbered in Table 1.

Results

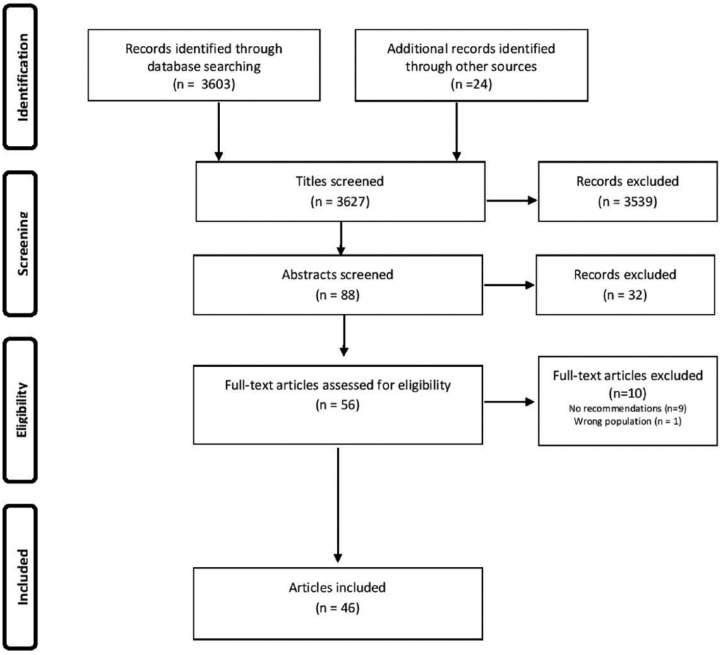

The search strategy generated 3,603 references, a further 24 references were sourced using manual searching of reference lists from identified studies. Among these, 88 potentially relevant abstracts were identified. Following review of the full-text of these articles, 46 eligible articles remained (see Table 1). Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the selection and exclusion process of included articles.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of Included Articles.

| # | Article | Design | Sample | Participant characteristics | Treatment styles | Treatment orientation | Theoretical constructs mentioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Addis and Cohane (2005); United States | Commentary | – | NS | I & G | NS | Social learning; psychodynamic; social constructionist & feminist approaches to masculinity |

| 2 | Bedi and Richards (2011); United States | Empirical, quantitative |

n = 37 age range = 19–55 (M = 35.1) |

NS | I | NS | Masculine gender role |

| 3 | Carr and West (2013); United States | Empirical, qualitative (incl. case study) | n = 1; age = 32 | African American male; depression | I | CBT; interpersonal | Multicultural, feminist and masculine role |

| 4 | Cheshire et al. (2016) | Empirical, quantitative | n = 102; age range = 31–49 | NS | I | Integrative; humanistic | Traditional masculine roles |

| 5 | Chovanec (2012); States | Empirical, mixed methods | n = 95; age range = 18–64 (M = 34) | Male domestic abuse perpetrators | G | Psychoeducation | Stages of change model |

| 6 | Cochran (2005); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | I | Clinical assessment | Masculine gender role socialization; gender role conflict; traditional masculine values; multiple masculinities |

| 7 | Cochran and Rabinowitz (2003), States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Males with depression | I, G, C | Clinical assessment; CBT; psychodynamic; self-psychology | Masculine gender role socialization; gender role conflict |

| 8 | Danforth and Wester (2014); States | Commentary | – | Male military veterans | NS | NS | Masculine gender role socialization; hypermasculine subculture; gender role conflict |

| 9 | Deering and Gannon (2005); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Male military veterans (with female clinicians) |

I | NS | Traditional masculinity; masculine gender role socialization; normative male alexithymia |

| 10 | Dienhart (2001); United States | Empirical, quantitative (Delphi study) | n = 36 | Family therapists specializing in gender issues | F | NS | Traditional gender roles; masculine mystique; stereotypical gender relations; male socialization; multiple masculinities |

| 11 | Emslie, Ridge, Ziebland, and Hunt (2007); UK | Empirical, qualitative |

n = 38 (16 male); age range = 18–66+ |

Mixed gender with depression | I | NS | Gender stereotypes; socially constructed gender roles; gender role conflict; hegemonic masculinity; traditional gender role |

| 12 | Englar-Carlson and Shepard (2005); United States | Commentary | – | Males in couples counseling | C | NS | Traditional masculine roles; gender role socialization; gender role conflict; gender-specific stigma; multiple masculinities |

| 13 | Evans et al. (2013); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Males with work–life balance difficulties | NS | Integrity model (existential/humanistic) | Traditional gender stereotypes |

| 14 | Genuchi, Hopper, and Morrison (2017); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Males in college | I | NS | Masculine gender role socialization; traditional masculine norms; normative male alexithymia |

| 15 | Gillon (2008) | Commentary | – | NS | I | Person-centered | Traditional masculinity; hegemonic masculinity; normative male gender role; gender role conflict; multiple masculinities; stages of change |

| 16 | Good and Robertson (2010); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | I | NS | Traditional masculine socialization; multiple masculinities; masculine gender role norms; masculinity-related problems |

| 17 | Good et al. (2005); United States | Commentary | – | NS | I & G | NS | Masculine role norms; traditional masculine socialization |

| 18 | Kierski and Blazina (2009); | Empirical, mixed methods | n = 31; age range = 25–68 (M = 44.5) | NS | I | NS | Traditional masculinity; masculine gender roles; gender normative behavior; gender role expectations; gender role conflict |

| 19 | Kiselica and Englar-Carlson (2010); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | I | Positive psychology | Traditional masculinity; positive masculinity; gender role conflict |

| 20 | Kivari, Oliffe, Borgen, and Westwood (2018); Canada | Empirical, mixed methods | n = 7; age range = 28–60 (M = 21.57) | Male military veterans | G | NS | Gender role socialization; gender role strain; traditional masculinity |

| 21 | Kosberg (2005); United States | Commentary | – | Older males | I & G | NS | Gender role conflict; masculine gender role socialization |

| 22 | Lawson et al. (2012); States | Commentary | – | Male domestic abuse perpetrators | G | CBT; Psychodynamic | Gender-based power differences; gender privilege; gender role norms; gender role resocialization |

| 23 | Lorber and Hector (2010); States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Male military veterans | NS | Psychoeducation; MI; emotion coaching; CBT | Traditional masculinity; masculine gender role socialization; gender role conflict |

| 24 | Mahalik et al (2005); States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | I | NS | Traditional masculinity; gender role norms; gender role conflict |

| 25 | Mahalik et al. (2003); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | I | NS | Masculine gender roles; gender role conflict |

| 26 | Mahalik et al. (2012); United States | Empirical, qualitative | n = 475; age range = 29–92 (M = 52.89); 64% male | Psychologists specializing in working with boys and men | NS | NS | Gender role socialization; traditional masculinity; masculine gender roles |

| 27 | McArdle et al (2012); Ireland | Empirical, qualitative | n = 15; age range = 23–35 (M = 29.47) | NS | G | CBT | Gender role socialization |

| 28 | McCarthy and Holliday (2004); United States | Commentary | – | NS | NS | NS | Multicultural; traditional male gender role; gender role conflict |

| 29 | Muldoon and Gary (2011); United States | Commentary | – | Male domestic abuse perpetrators | NS | NS | Stages of change; multicultural |

| 30 | Nahon and Lander (2013); Canada | Commentary | – | NS | G | Integrity model (existential/humanistic) | Multiple masculinities; positive masculinity; gender role re-evaluation |

| 31 | Nahon and Lander (2014); Canada | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | I | Integrity model (existential/humanistic) | Gender role strain; positive masculinity |

| 32 | Primack, Addis, Syzdek, and Miller (2010); United States | Empirical, quantitative | n = 6; age range = 38–65 | Males with depression | G | CBT | Masculine gender role norms; gender role socialization |

| 33 | Rabinowitz and Cochran (2007); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Males with depression | NS | NS | Gender role norms; traditional masculinity |

| 34 | Reed (2014); United States | Empirical, qualitative | n = 6l; age range = 18–24 | Young males | I | NS | Traditional masculinity; gender role norms |

| 35 | Reigeluth and Addis (2010); United States | Commentary | – | NS | NS | NS | Masculine gender roles; traditional masculinity; gender socialization |

| 36 | Richards and Bedi (2015); United States | Empirical, quantitative | n = 76 men; age range 19–63 (M = 35.6) | NS | I | NS | Traditional masculinity; gender role norms; gender role conflict; multiple masculinities; masculine identity |

| 37 | Robertson and Williams (2010); United States | Commentary | – | Males in high accountability professions (e.g., doctor/lawyer) | I & G | NS | Masculine gender role socialization; traditional masculinity |

| 38 | Schermer (2013); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | G | Narrative therapy | Traditional masculinity; male sex roles |

| 39 | Seidler, Rice, Oliffe, et al. (2017) | Empirical, qualitative | n = 20 men; age range = 23–64 (M = 39) | Males with depression | I | NS | Dominant masculine ideals; multiple masculinities; masculine gender norms |

| 40 | Spandler et al. (2014) | Empirical, qualitative | n = 46 (40 men; 6 facilitator) | NS | G | CBT | Modern masculinity |

| 41 | Spendelow (2015); UK | Review | – | Males with depression | I & G | CBT | Gender role socialization; traditional masculinity; gender role schema theory; gender role conflict; multiple masculinities |

| 42 | Sternbach (2003); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | NS | G | NS | Multiple masculinities |

| 43 | Syzdek et al. (2014); United States | Empirical, quantitative | n = 23; age range = 19–57 (M = 37.65) | Males with internalizing symptoms | I | MI | Traditional masculinity |

| 44 | Westwood and Black (2012); Canada | Commentary | – | NS | I & G | NS | Traditional masculinity; gender socialization |

| 45 | Wong and Rochlen (2005); United States | Commentary | – | NS | NS | NS | Gender role socialization; gender role conflict; traditional masculinity; masculine gender role norms |

| 46 | Zayas and Torres (2009); United States | Commentary (incl. case study) |

– | Latino males | NS | NS | Latino masculine identity; traditional masculinity; gender role socialization |

Note. NS = nonspecified; I = individual; G = group; F = family; C = couples; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; MI = motivational interviewing.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Article Characteristics

The reviewed articles included peer-reviewed commentary or review articles, qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research. The full characteristics of each article are detailed in Table 1. The following section provides an overview of this information.

Year and location of studies

All included articles were published between 2000 and 2017. The majority (n = 38, 83%) were conducted in North America.

Article type

Thirty articles (65%) were without original data and were categorized as a commentary or review. Seven (15%) employed qualitative methods and six (13%) quantitative methods. The remaining three articles (7%) reported both qualitative and quantitative data, warranting description as mixed methods studies

Sample and participant characteristics

In total, the empirical studies reported data on 1,014 participants. Sample sizes ranged from 1 to 475. Five studies analyzed data from clinicians working with men. All but one (Emslie et al., 2007) included a male-only sample or focus.

Twenty-three articles (50%) focused on all men’s general nonspecific mental health concerns (e.g., any presenting problem), seven (15%) specifically on men with depression, four (9%) on military veterans, three (7%) on perpetrators of domestic violence, two (4%) on family or relationship functioning, treating ethnic minorities and young men respectively, and one (2%) each on treating work–life balance issues, men in high-accountability professions and older men.

Treatment modality and orientation

Fifteen (33%) articles offered recommendations specifically for individual therapy, nine (20%) for group therapy, seven (15%) referenced both, and two (4%) focused on men in a family therapy context. The remaining thirteen (28%) articles had general recommendations that did not specify treatment modality.

Five (11%) articles framed their recommendations based on mixed orientations (e.g., psychodynamic & cognitive behavioral therapy; CBT), four (9%) articles framed their recommendations regarding a CBT treatment orientation alone, three (7%) referred to a self-described “integrity” (existential/humanistic) model of psychotherapy, and one (2%) to narrative therapy, psychoeducation, clinical assessment, positive psychology, person-centered and motivational interviewing respectively. The remaining 28 (76%) articles did not refer to specific psychotherapy models, instead referring to treatment generally.

Thematic Analysis of Findings

Thematic analysis of the 46 articles revealed four distinct, though interconnected themes. All focused on therapeutic process and how clinicians can modify the structure of therapy, increase their focus on gender, and tailor their communication and relational style in order to improve engagement with male clients. These four themes are summarized below and described in detail in Table 2.

Building in gender socialization

Fifteen articles recommended including consideration of gender role socialization as key to understanding how a client’s past and present environments shape his alignment to masculine norms. Such client conceptualization should explore how ideas about gender, stemming from one’s developmental and cultural contexts, links to current stressors and impact functioning. Seven articles recommended viewing self or societal stigma surrounding psychological treatment through a gendered lens (e.g., help-seeking avoidance linked with fear of appearing a “weak” man). Eight articles made specific suggestions to review the client’s gender role cognition (e.g., power; “I must be powerful or I am worthless”) and gender role conflict (e.g., levels of emotional restrictiveness manifesting in externalizing behaviors) respectively. These psychoeducational and cognitive approaches to understanding a client’s gender socialized ideals were framed as alleviating discomfort or shame men might experience entering treatment. Nine articles suggested that assessing for conformity (or nonconformity) to traditional masculine norms may aid understanding the client’s symptoms (e.g., externalizing distress through aggression or substance misuse) and what maintains these symptoms. For example, understanding the benefits and costs of a male client’s pursuit of status and power and how these rigid expectations are contributing to his feelings of worthlessness.

Five articles recommended that in order to more effectively respond to and engage with men, clinicians need to embrace the pluralities of masculinity and consider a male client’s diverse and complex perspectives of being a man. Through this process of exploring the seemingly contradictory or overlapping experiences or expressions of masculinities within men, clinicians can shift from a generalizing, sex-differences framework toward a more men-centered approach that appreciates individual and intra-individual variability. Five articles suggested focusing specifically on a strength-based approach to conceptualizing the client’s unique masculinities; reinforcing that the client may already possess many strengths useful in maintaining their mental health (e.g., problem-solving ability, courage, and worker–provider beliefs). However, all of these strengths were identified through the lens of traditional masculine norms that are also, as previously discussed, potentially detrimental to the mental health of men. These traditional strengths of masculinity were offered at the expense of describing less common subordinate or marginalized masculine norms (e.g., homosexuality; selflessness).

Nineteen articles recommended that clinicians regularly explore their own internal gender role stereotypes, assumptions, and biases regarding masculinity and the effects these may have on clients, treatments, and therapeutic relationships. Two articles made reference to how rigid masculine gender roles (e.g., power or dominance) can have ramifications on engaging with a female clinician and recommended that should such a client present for treatment, the female clinician take into account the potential for sexual transference or male “fear of the feminine” impacting treatment engagement and the therapeutic relationship.

Clarifying structure

Eight articles recommended transparently describing and clarifying what treatment involved and how individual sessions would be structured. This approach was taken to overcome many men’s ambivalence, disconnection, or fearfulness of mental health care. Three articles recommended breaking down treatment options and their components. Offering a “roadmap” of the upcoming treatment was seen to clarify expectations and reduce client mistrust. Sixteen articles detailed how to navigate these structure expectations. These articles recommended clinicians purposefully orient and educate clients in their role, responsibilities and accountabilities, and how these differ from those of the clinician. They also recommended outlining how treatment works, how long it may take, and what progress may look like. Five articles referred to addressing self-management or self-regulation with male clients as a key expected outcome of treatment. This, in turn, was seen to offset fears of on-going dependency within the relationship.

Thirteen articles recommended creating and targeting measurable short-term goals for treatment. This was seen as an effective way to maintain men’s motivation in treatment. It was recommended that when working with male clients, goals be iteratively revised to ensure the client was considering and contributing to their ongoing care and taking into account their previous progress (and any current difficulties) with the clinician. Six articles recommended that to accomplish goals, an action-oriented approach to treatment was helpful, focusing on skills practice, review, and feedback of progress. To ensure clarity between clinician and client, four articles recommended clinicians reiteratively link with past session skills in order for skills to be further developed, built upon and contextualized within treatment; and six articles suggested being constructive and open-ended when questioning male clients on goal attainment and progress.

Building rapport and a collaborative relationship

Twenty-two articles emphasized specific core skills for therapists to consider for establishing rapport with male clients. Building a strong therapeutic alliance was viewed as key to counteract feelings of ambivalence, uncertainty, disconnection, and stigma towards treatment. Clinicians were encouraged to take a normalizing, encouraging, and validating stance with a view to putting male clients at ease in what may feel like a foreign, or for some, a shame-inducing environment. This process was suggested to set the foundation for a therapeutic relationship built on trust and honesty. While these micro-skills were referred to in an open-ended, generic manner, some articles made reference to validating and normalizing any discomfort seen, difficulties in emotional communication, being vulnerable, or trusting the clinician. There was specific reference to clinicians being attuned to cultural or ethnic backgrounds that may increase some men’s feelings of isolation or misunderstanding. Nineteen articles proposed that self-disclosure by the clinician could be important when working with men. Self-disclosure was conceptualized as a means to purposefully break down perceived hierarchical dynamics of the therapeutic relationship, and promote honesty and equality. Further, it was recommended that the style and frequency of self-disclosure be consistent, with clinicians avoiding intermittent withdrawal. This modeling of reliability in the therapeutic relationship highlighted the power of this experience to act as a “re-socializing” experience for many male clients.

Twenty-three articles made recommendations on how to extend the aforementioned micro-skills to build a strong sense of mutuality, focused on a strength-based approach in relating. Exploring and incorporating noble aspects of the client’s masculinity into treatment (e.g., fatherhood, heroism, self-reliance), rather than solely seeking to address their shortcomings, was reported to bolster rapport and engagement. Fourteen articles suggested that acceptance of misgivings, awkwardness, or communication difficulties in male clients had greater adaptive power than identifying these behaviors as deficient. Five articles recommended employing a more person-centered approach to treatment; remaining open-minded, attentive, and accepting in “meeting the client where they are” (Good & Robertson, 2010, p. 311) was viewed as more effective than expecting conformity to specific masculine norms.

Eighteen articles recommended the importance of balanced, reciprocal, nondirective, and collaborative therapeutic relationships. There was an emphasis on closing the gap between clinician and client, shifting from a paternalistic or traditional expert–patient relationship to one of equality. This was conceptualized to reduce possible feelings of incompetency, worthlessness, alienation, and isolation experienced by some men. It was frequently argued that male clients should be genuinely affirmed to view themselves as expert in their experience. Collaborative approaches were seen to allow clients to feel active and empowered in their health care, to engage and share in decision-making. Rather than the clinician being in charge, embracing and building on masculine norms of strength, power, and independence through promotion of autonomy (over dependency) was recommended to increase engagement. In aiming for collaboration, reciprocity, and purposeful leveling of power, male client’s resistance to change can be reduced as they realize their input, effort, and time is valued and needed.

Tailoring language

Fifteen articles emphasized the importance of employing male-oriented language. These recommendations affirmed adopting styles of communication conforming to traditional masculine norms (where appropriate), characterized as action-oriented, future-focused, and progress-driven communications (e.g., offering symptoms as distinct problems requiring solving; “getting hard work done” through education, upskilling, and repairing). This was highly pertinent when referring to labels for therapeutic work or diagnoses, the latter often regarded as pathologizing and stigmatizing. Recommendations also involved describing treatment such as coaching or consultation to “move past barriers and blocks.” Seven articles referred to more general use of informal or colloquial language (e.g., swearing) and humor to engender comradery, comfort, and feelings of equality between client and clinician. Six articles recommended using relevant metaphors that connect with male clients’ interests (e.g., related to sporting or computing) in order to facilitate nonthreatening avenues of communicating and understanding emotional material and therapeutic concepts.

Six articles recommended that communication with male clients be brief, direct, and specific. This was aimed at promoting an experience of doing over talking. Two articles highlighted the importance of nonverbal communication and how posture, physical mannerisms, eye-contact, handshake, and silence are powerful tools a male client is able to recognize and connect with. Rather than distance or dominance (e.g., scientific jargon), reflecting ease through nontraditional therapeutic interaction with the client both verbally and nonverbally, was suggested as a means to further engage the client. This could be through the incorporation of play modalities and movement (e.g., walking outside; kicking a ball) and creating a shared therapeutic language through normalizing statements like “me too.”

Discussion

Men’s reticence toward mental health help-seeking has long been a subject of concern, with speculation as to the reasons for their reluctance and how this trend might be rectified. Afforded here is a synthesis of recommendations regarding what may attract and retain men in psychological treatment. Providing an engaging treatment approach from the outset may curb many men’s experience of the “revolving door phenomenon” related to patterns of disengagement, dropout, and subsequent relapse followed by reuptake of services in crisis periods (Nahon & Lander, 2014). This pattern challenges limited mental health system resources, impacts economic efficiency and likely contributes to men’s high suicide rates (Pederson & Vogel, 2007). The strategies outlined in this review point to the need to overcome ambivalence through establishing and sustaining trust, respect and understanding between clinicians and male clients. The recommendations outlined here point to the early, collaborative construction of a therapeutic alliance that can withstand later process strategies including confronting the man’s rage, guilt, grief and fears. This is essential so the client perceives what is often an aversive experience as a process aimed at achieving insight and overcoming challenges rather than feeling attacked or undermined.

Spanning almost two decades, the current systematically identified literature is diverse in treatment style and modality, target population and methodology; yet consistent in the recommendations made within these articles regarding the psychological treatment processes most engaging for men. Overall, the current findings suggest that providing engaging treatment for men requires a combination of; (a) purposeful and targeted use of specific therapeutic techniques (e.g., normalizing; validating) that contribute to the development of a collaborative, therapeutic relationship; (b) clarifying a transparent, goal-focused and action-oriented structure; (c) tailoring language to have a dynamism focus that is direct and free of jargon and; (d) requiring clinicians to overcome their own gendered assumptions to fully evaluate and work to the client’s gender socialization and construction of masculinities.

The themes drawn from the current scoping review offered recommendations largely matching key treatment books published in the same period (e.g., Brooks, 2010; Englar-Carlson et al., 2014; Rochlen & Rabinowitz, 2014) albeit with less contextual and temporal depth for clinicians to consider. The relatively generic nature of many of these recommendations can be linked to the number of commentaries and opinion pieces lacking primary data to make empirical assertions. Had these articles offered empirical analyses in addition to experiential evidence, the limits of their implications and application may have been waylaid. However, the strength of this review is that, in synthesizing 46 articles, links were able to be drawn that fill many of these gaps by clustering recommendations consistently found within and across the articles. Where quantitative results were explored (e.g.,Primack et al., 2010; Syzdek et al., 2014) the outcome of interest was the impact on the male clients’ mental health rather than their engagement or the relative strength of the therapeutic alliance. One exception was Chovanec’s (2012) domestic abuse program, where increased engagement in treatment was reported over time. Therefore, while therapeutic process variables were reviewed, only one study reported them as pre–post outcomes. Despite this knowledge gap, a body of qualitative literature offers rich insights pointing to the usefulness of employing clinical recommendations, from the perspectives of male clients and their clinicians. Nonetheless, engagement with mental health treatment[s] is a vital measure to gauge success when working with men in future.

While Mahalik et al. (2012) gained recommendations from clinicians in the field, this review included peer-reviewed literature addressing clinical practices with male clients, and recommendations for improving psychological treatment. The main extension on Mahalik et al.’s (2012) themes afforded by the current review was the breakdown of specific strategies focused on facilitating a transparent treatment structure and encouraging autonomy within a collaborative working relationship (e.g., Richards & Bedi, 2015; Seidler, Rice, Oliffe, et al., 2017). Furthermore, building from Mahalik et al.’s (2012) advice for developing sensitivity to gender socialization when working with men, consideration was given to how the therapy process can be enhanced by developing an appreciation of each male client’s construction of the factors influencing his masculinity. Finally, the current review included fifteen articles published post-2012 (i.e., after Mahalik’s taxonomy was published), making it a timely update of an exponentially growing literature. The best example of this is the inclusion of more recent recommendations expounding positive, strength-based conceptualizations of masculinities (e.g., Genuchi et al., 2017; Kivari et al., 2018).

As noted above, central in the current review was gender, with an array of masculinities chronicled as key considerations amid consensus about how specific masculine norms might be used to more fully engage and retain men in mental health-care services. Importantly, these norms were primarily those of traditional masculinity, the dominant western performativity, linked previously with psychological treatment resistance, ambivalence, and disengagement (Pederson & Vogel, 2007). Results highlight the consistency across articles referring to theoretical constructs like “gender socialization” and “traditional masculinity.” However, the reasoning for this choice of terminology or theoretical viewpoint was often assumed based on reference to previous literature and not expounded upon to aid the reader’s interpretations.

Of note, there has been a shift from viewing traditional masculinity as “deficit” towards greater acceptance and integration of strength-based approaches (Sloan, Gough, & Conner, 2010). However, the current review highlighted that despite approximately 50% of the articles providing peripheral, surface-level suggestions for taking note of the “noble” or positive aspects of male client’s masculinity, only around 10% provided adequate detail regarding devising and implementing a strength-based conceptualization, assessment, and treatment for men (e.g., Englar-Carlson & Shepard, 2005; Kiselica & Englar-Carlson, 2010; McCarthy & Holliday, 2004; Nahon & Lander, 2013, 2014; Wong & Rochlen, 2005). Moreover, within this positive masculinity model, only those behaviors aligned with traditional masculinity were framed as positive.

In prioritizing traditional masculinity alone over the complex, multiple masculinities experienced by men, the vast majority of these articles highlight that depth and nuance are required when considering how to engage a heterogenous male demographic (Seidler, Rice, River, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2017). Only 10% of the included articles made reference to addressing men-centered approaches to incorporate male client’s unique masculinities (e.g., Cochran, 2005; Dienhart, 2001; Englar-Carlson & Shepard, 2005; Spendelow, 2015; Sternbach, 2003), and a major focus on white, heterosexual men was left only five percent of articles with a specific, in-depth focus on minority groups and/or the intersectionality of culture and masculinity (Carr & West, 2013; Zayas & Torres, 2009). If recommendations focus entirely on traditional masculinity, dismissing more nuanced approaches to the diverse masculinities experienced and expressed by men, clinicians may lack the ability to anticipate and respond to diverse, context-dependent masculine norms (across life course, history place and an array of social determinants of health).

By extension, the potential for contextually emergent norms of masculinity that can benefit men’s mental health (i.e., soliciting help as a means to effective self-management) will be overlooked, instead highlighted amidst a deficit model yielding men’s poor outcomes. Indeed, the majority of articles in this review took a universal (etic) perspective in homogenizing their male target group. Instead, what has long been advised, but is still needed, is a culturally specific (emic) approach to men and masculinities in psychological treatment that aims for a multicultural positioning of a man’s socialization (Liu, 2005; Seidler, Rice, River, et al., 2017; Zayas & Torres, 2009).

The Barriers to Clinical Translation of Recommendations

The reasons the aforementioned treatment recommendations have yet to be effectively translated into practice must be considered to ensure significant shifts in the field. Cochran (2005) suggested that without large scale controlled trials exploring the efficacy of specifically tailored treatments for men, the field would struggle to develop. A decade later, Rochlen and Rabinowitz (2015) stated we “remain largely in the dark when it comes to knowing how to help men” (p. 3). The lack of empirical foundation and systematic critique in the wake of Mahalik et al.’s (2012) taxonomy may explain the absence of high quality clinical trials in the field, and suggests further integration and clarification is needed. The undertaking of clinical studies relies heavily on effective committed research partnerships that ensure the recruitment of male participants, and the incorporation of findings to clinical practice. Appealing to masculine norms of altruism and comradery to incentivize research participation (in the sense that by doing so, would help advance and improve treatment for other men) has a strong culture in the urological cancer context and should be applied in the mental health space too. Such partnerships can also advance lobby and application for gender-competence training to aid recruitment and uptake of what is learnt from those studies. Moreover, employing co-design strategies where the male mental health-care consumer is given equal voice to that of the clinician or researcher through focus groups and evaluative capacity for new content when developing male-adaptations in treatment trials, for instance, is key.

Strokoff, Halford, and Owen (2016) conducted a review of 15 studies employing male-targeted psychological treatment approaches and identified only a single, small randomized study examining a treatment specifically tailored for men. This study investigated the use of a brief alliance-building intervention, known as gender-based motivational interviewing (GBMI), in a community-based sample of men with symptoms of anxiety and depression and no statistically significant effects were reported (Syzdek, Addis, Green, Whorley, & Berger, 2014). A subsequent randomized trial of GBMI in a sample of 35 college men identified a significant increase in seeking help directed towards family members (Syzdek et al., 2016). Moreover, in another review of men’s groups, only one of twelve studies identified for men in group counseling was conducted in a clinical setting, and over half were addressing men dealing with addiction or perpetrators of abuse (Nahon & Lander, 2013).

Amidst a substantial body of qualitative work exploring men’s experiences with and treatment for depression and anxiety, there is relatively little quantitative empirical research building on this work investigating the impact of tailoring these psychological treatments targeting common mental health challenges in men. Primack et al. (2010) conducted the first pilot trial of a workshop designed to reduce depressive symptoms in men using a modified CBT treatment, focused on psychoeducation and discussing adherence to various masculine norms. This pilot included a sample of five men and saw decreases in self-reported symptoms. However, the rarity of targeted empirical work in a clinical setting underpins the disconnect between the saturation of recommendations and their currently diminutive evidence base. Men’s mental health will continue to fail to garner policy consideration, clinical attention, and funding needed to combat issues like substance overuse, physical violence, and suicide until there is strong, rigorous empirical evidence supporting the implementation of the series of treatment recommendations proposed.

It has been proposed that many existing treatment recommendations for men are simply therapy “micro-skills,” or “good therapy practice,” as they do not represent a significant departure from existing knowledge (Good et al., 2005). Suggesting recommendations including orienting, normalizing, validating and motivating clients in treatment are gender-neutral facets of psychotherapy is true, but does not account for why and how they may be key to effectively working with men to overcome common mistrust and ambivalence in treatment (Mahalik et al., 2012). Importantly, such recommendations must be considered in the context of the other, male-specific recommendations (e.g., tailoring language; reviewing socialization) where they may be especially useful. Indeed, if the present recommendations were employed purposefully, reliably, and effectively with men, and gender awareness was common practice, challenges with engagement and dropout may be reduced. Therefore, promoting the restructuring or amplification of such skill recommendations may be key to address some men’s problematic engagement in psychological treatment (Good et al., 2005; Mahalik et al., 2012; Seidler, Rice, Oliffe, et al., 2017).

Clinicians should note these recommendations, while aiming to be generalizable, may not conform to one’s specific model of practice, or every male client seen. Importantly, regardless of the working model, a clinician should aim to understand their own gendered experience and expectations as a critical reflective task that takes place in training and development outside the consulting room. As for the client’s gendered experience, the applicability or appropriateness of some recommendations within specific treatment frameworks (e.g., CBT vs. psychodynamic psychotherapy) depends on the timeline and clinical depth achievable with the client and their presenting concern(s). In a short-term, largely behaviorally oriented treatment like CBT, a deep exploration of the client’s internalized gender roles and their source may not be necessary or useful. Nonetheless, while the client’s masculinity may be outside the scope of such an intervention, assessing and formulating with the client’s gender in mind will help clarify approaches to cognitive restructuring, in a similar way to multicultural factors. Cognitive distortions or biases regarding a man’s beliefs around emotional control, power and success are means for exploring overarching withdrawal, avoidance or catastrophizing through self-monitoring and reality testing (Mahalik, 1999). Moreover, in challenging rigid beliefs, the clinician may inadvertently introduce and foster the adaptive exploration of multiple masculinities (Spendelow, 2015). Comparatively, psychodynamic work focused on unconscious processes and attachment-related issues may require a more in-depth review of the definition and performativity of masculinity by the client. A psychodynamic formulation of male development may focus on a masculine-specific vulnerability to loss or grief to open discussions on transference and resistance as they manifest in the therapeutic relationship (Pollack, 2005). Therefore, while the depth of focus and criticality of masculinities may differ, both models stress an empathic attunement and awareness from the clinician in striving to challenge cultural proscriptions against men’s vulnerability or depressed mood and replace them with more fluid, adaptive masculinities (Cochran & Rabinowitz, 2003)

The translation of existing recommendations into practice may also be limited by a narrow pathological view of traditional masculinity, that privileges heterosexual, white middle class masculinity over the pluralistic and often-contradictory masculinities experienced by most men (Connell, 1995; Seidler, Rice, River, et al., 2017). Negative biases and attitudes related to masculinity inevitably impact clinicians themselves (Nahon & Lander, 2013). For example, the masculinity beliefs and biases held by clinicians regarding what are, and are not, appropriate gendered behaviors, may impact their approach to male clients (Owen, Wong, & Rodolfa, 2009, 2010). Highlighting this, Seymour-Smith, Wetherell and Phoenix (2002) reported health-care practitioners critiqued traditional masculinity for its detrimental effects on men, but that concurrently, those men who defied these norms were rendered “invisible.” Therefore, the importance of considering and employing male-centered treatment recommendations within a clinical landscape, often pathologizing aspects of masculinity, has been devalued. This is most obvious in that a minority of U.S. clinical psychology doctorate programs included gender competency training, highlighting the profound gap between the number of resources that exist and their application (Mellinger & Liu, 2006).

As stated above, the majority of existing research trials focus on traditionally masculine samples (e.g., war veterans; violent offenders; Nahon & Lander, 2013), without addressing the complexity and diversity within and across men. This review highlights that while attempts have been made to broaden this scope (e.g., Zayas & Torres, 2009), they are few and far between, and clinicians will continue to be complicit in addressing and problematizing traditional masculinity, if a decisive shift in scholarly emphasis is not undertaken. Future empirical research exploring the perspectives and preferences of men of ethnic minorities and sexually diverse backgrounds will offer a requisite move away from the sex differences research cul-de-sac (e.g., male vs. female), currently entrenched in the deficit-based, pathologizing of masculinity. Made available will be within group diversities, whereby masculinities, and strength-based research and practices can be chronicled. Continuing to view masculinity as a singular male sex role obscures multiple masculinities, and the complex “intersections” with structures and social determinants of health including race, sexuality and culture (Connell, 1995; Griffith, 2012).

To operationalize, test and measure the efficacy of the aforementioned process strategies in treatment with men, the following suggestions are made. The first step to improving the clinician’s approach is through gender competence training to advance awareness, knowledge and skills in learning these strategies through active, experiential methods (e.g., role play, case studies). In mirroring a multicultural competency approach (Liu, 2005) clinicians can learn to reflect on their own gender socialization and its impact on treatment (e.g., identifying their own stereotypes and biases that may affect clinical encounters), which can be formally assessed using attitudinal measures of change. Second, the efficacy of the included recommendations targeting the structure of psychological treatment through goal-oriented interventions with men and building strong rapport through a collaborative relationship can be evaluated through client satisfaction feedback including the quality of the therapeutic alliance (Ardito & Rabellino, 2011). Similarly, when employing tailored language in treatment with men, clinicians can review the relative levels of engagement on a prospective basis through questionnaires and via dropout data. Such approaches will provide insight into the effectiveness of these strategies.

Limitations

This review has several limitations that should be considered. First, the choice of databases may not have been entirely exhaustive, though hand searching of reference lists aimed to increase this scope. The large number of retrieved articles that were excluded suggests that the search strategy may have been too broad. That said, as the first scoping review in an emergent field, casting a wide net seemed appropriate to ensure all potentially relevant peer-reviewed reports were retrieved. Moving forward, future work might benefit from using more prescriptive keyword searches, given the volume of non-mental health-related material identified in the current scoping review.

Second, the relative importance of the themes derived in the thematic analysis should not be assumed based solely on the number of studies reporting similar findings. Results highlighted that consistency and re-reporting of findings across studies was common, suggesting that authors were not providing unique insight, but recommendations deemed worthy of repetition. However, this “count” method provides a useful ordering of hegemonic findings across samples, an insight into current trends, and generates questions of why certain recommendations are deemed worthy of repetition and revealing gaps in the research. Finally, no quality assessment was undertaken, and given the high proportion of included commentaries, the reported results are undoubtedly subjective in nature. Nonetheless, the overall consistency in recommendations across article type suggests those reporting their clinical experience may be working in a similar approach to that which underpins empirical investigations.

Conclusions

This review provides a synthesis of an important but somewhat disconnected literature addressing effective practices for men’s psychological treatments. The principles distilled as having some consensus across empirical studies and clinical commentaries offer much to take forward both in terms of future research directions and potentially useful clinical practices. This scoping review does the work of lifting principles about working with men in the mental health space, and offers guidelines, which might be usefully formalized and tested with men and clinicians. In drawing on the gendered dimensions of men’s mental health provision, much can be gained to advance the mental health of men and their families. Critical is ensuring uptake of what is known in this regard as well as the continuation to build upon these emergent insights to fully engage men with psychological treatment. The current review exemplifies that data-driven understanding of what works to engage men in psychological treatment is still at a nascent stage.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, COMBINED_SUPPLEMENTARY for Engaging Men in Psychological Treatment: A Scoping Review by Zac E. Seidler, Simon M. Rice, John S. Ogrodniczuk, John L. Oliffe and Haryana M. Dhillon in American Journal of Men’s Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Publication funding was provided by the Men’s Health Research Program at UBC – www.menshealthresearch.ubc.ca

ORCID iDs: Zac E. Seidler  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-1554

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6854-1554

John L. Oliffe  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7645-1869

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7645-1869

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material is available for this article online.

References

- Addis M. E., Cohane G. H. (2005). Social scientific paradigms of masculinity and their implications for research and practice in men’s mental health. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 633–647. doi:10.1002/jclp.20099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2000). Guidelines for psychother- apy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist, 55, 1440–1451. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.12.1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58, 377–402. doi:10.1037/0003- 066X.58.5.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2004). Guidelines for psychological practice with older adults. American Psychologist, 59, 236–260. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2007). Guidelines for psychological practice with girls and women. American Psychologist, 62, 949–979. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.9.949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardito R. B., Rabellino D. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: Historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R., Hall B. J., Doyle J., Waters E. (2011). ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. Journal of Public Health, 33(1): 147–150. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R. P., Richards M. (2011). What a man wants: The male perspective. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 48(4), 381–390. doi: 10.1037/a0022424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boterhoven De, Haan K. L., Lee C. W. (2014). Therapists’ thoughts on therapy: Clinicians’ perceptions of the therapy processes that distinguish schema, cognitive behavioural and psychodynamic approaches. Psychotherapy Research, 24(5), 538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks G. R. (2010). Beyond the crisis of masculinity: A transtheoretical model for male-friendly therapy. In Brooks G. R. (Ed.), Beyond the crisis of masculinity: A transtheoretical model for male-friendly therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Calear A. L., Batterham P. J., Christensen H. (2014). Predictors of help-seeking for suicidal ideation in the community: Risks and opportunities for public suicide prevention campaigns. Psychiatry Research, 219(3), 525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr E. R., West L. M. (2013). Inside the therapy room: A case study for treating African American men from a multicultural/feminist perspective. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(2), 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire A., Peters D., Ridge D. (2016). How do we improve men’s mental health via primary care? An evaluation of the Atlas Men’s Well-being Pilot Programme for stressed/distressed men. BMC Family Practice, 17(1), 13. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0410-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chovanec M. G. (2012). Examining engagement of men in a domestic abuse program from three perspectives: An exploratory multimethod study. Social Work with Groups, 35(4), 362–378. doi: 10.1080/01609513.2012.669351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran S. V. (2005). Evidence-based assessment with men. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 649–660. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran S. V., Rabinowitz F. E. (2003). Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(2), 132–140. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.34.2.132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. (1995). Masculinities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Danforth L., Wester S. R. (2014). Gender-sensitive therapy with male servicemen: An integration of recent research and theory. Special Issue: Research on Psychological Issues and Interventions for Military Personnel, Veterans, and Their Families, 45(6), 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J. J., Higgins J. P., Altman D. G. (2008). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Higgins J. P., Green S. (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002 [Google Scholar]

- Deering C., Gannon E. J. (2005). Gender and psychotherapy with traditional men. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 59(4), 351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienhart A. (2001). Engaging men in family therapy: Does the gender of the therapist make a difference? Journal of Family Therapy, 23(1), 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Emslie C., Ridge D., Ziebland S., Hunt K. (2007). Exploring men’s and women’s experiences of depression and engagement with health professionals: More similarities than differences? A qualitative interview study. BMC Family Practice, 8, 43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englar-Carlson M., Evans M. P., Duffey T. (2014). Foreword. A counselor’s guide to working with men. Alexandria, VA: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Englar-Carlson M., Shepard D. S. (2005). Engaging men in couples counseling: Strategies for overcoming ambivalence and inexpressiveness. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 13(4), 383–391. doi: 10.1177/1066480705278467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A. M., Carney J. S., Wilkinson M. (2013). Work-life balance for men: Counseling implications. Journal of Counseling and Development, 91(4), 436–441. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00115.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty A. S., Proudfoot J., Whittle E. L., Player M. J., Christensen H., Hadzi-Pavlovic D., Wilhelm K. (2015). Men’s use of positive strategies for preventing and managing depression: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 188, 179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdas P. M., Cheater F., Marshall P. (2005). Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 616–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuchi M. C., Hopper B., Morrison C. R. (2017). Using metaphors to facilitate exploration of emotional content in counseling with college men. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 25(2), 133–149. doi: 10.1177/1060826516661187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillon E. (2008). Men, masculinity and person-centered therapy. Special Issue: Gender and PCE Therapies, 7(2), 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Good G. E., Robertson J. M. (2010). To accept a pilot? Addressing men’s ambivalence and altering their expectancies about therapy. Psychotherapy, 47(3), 306–315. doi: 10.1037/a0021162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good G. E., Thomson D. A., Brathwaite A. D. (2005). Men and therapy: Critical concepts, theoretical frameworks, and research recommendations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 699–711. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M. (2012). An intersectional approach to men’s health. Journal of Men’s Health, 9(2), 106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. G., Diminic S., Reavley N., Baxter A., Pirkis J., Whiteford H. A. (2015). Males’ mental health disadvantage: An estimation of gender-specific changes in service utilisation for mental and substance use disorders in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(9), 821–832. doi: 10.1177/0004867415577434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. L., Oliffe J. L., Kelly M. T., Galdas P., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Johnson L. J., … Ogrodniczuk S. J. (2012). Men’s discourses of help-seeking in the context of depression. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34(3), 345–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierski W., Blazina C. (2009). The male fear of the feminine and its effects on counseling and psychotherapy. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 17(2), 155–172. doi: 10.3149/jms.1702.155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica M. S., Englar-Carlson M. (2010). Identifying, affirming, and building upon male strengths: the positive psychology/positive masculinity model of psychotherapy with boys and men. Psychotherapy, 47(3), 276–87. doi: 10.1037/a0021159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivari C. A., Oliffe J. L., Borgen W. A., Westwood M. J. (2018). No man left behind: Effectively engaging male military veterans in counseling. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(2), 241–251. doi: 10.1177/1557988316630538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosberg J. I. (2005). Meeting the needs of older men: Challenges for those in helping professions. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 32(1), 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson D. M., Kellam M., Quinn J., Malnar S. G. (2012). Integrated cognitive–behavioral and psychodynamic psychotherapy for intimate partner violent men. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 190–201. doi: 10.1037/a0028255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. doi: 10.1186/1784-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. M. (2005). The study of men and masculinity as an important multicultural competency consideration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 685–697. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber W., Garcia H. A. (2010). Not supposed to feel this: Traditional masculinity in psychotherapy with male veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(3), 296–305. doi: 10.1037/a0021161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R. (1999). Incorporating a gender role strain perspective in assessing and treating men’s cognitive distortions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30(4), 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R., Good G. E., Englar-Carlson M. (2003). Masculinity scripts, presenting concerns, and help seeking: Implications for practice and training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(2), 123. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R., Good G. E., Tager D., Levant R. F., Mackowiak C. (2012). Developing a taxonomy of helpful and harmful practices for clinical work with boys and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(4), 591–603. doi: 10.1037/a0030130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik J. R., Talmadge W. T., Locke B. D., Scott R. P. J. (2005). Using the conformity to masculine norms inventory to work with men in a clinical setting. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 661–674. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays N., Roberts E., Popay J. (2001). Synthesising research evidence. In N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, & N. Black (Eds.), Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle S., McGale N., Gaffney P. (2012). A qualitative exploration of men’s experiences of an Integrated Exercise/CBT Mental Health Promotion Programme. International Journal of Men’s Health, 11(3), 240–257. [Google Scholar]