Abstract

Objectives

To assess the long-term safety and efficacy of ixekizumab, an IL-17A antagonist, in patients with active PsA.

Methods

In SPIRIT-P2 (NCT02349295), patients (n = 363) with previous inadequate response to TNF inhibitors entered the double-blind period (weeks 0–24) and received placebo or ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks (IXEQ4W) or every 2 weeks (IXEQ2W) following a 160-mg starting dose at week 0. During the extension period (weeks 24–156), patients maintained their original ixekizumab dose, and placebo patients received IXEQ4W or IXEQ2W (1:1). We present the accumulated safety findings (week 24 up to 156) at the time of this analysis for patients who entered the extension period (n = 310). Exposure-adjusted incidence rates (IRs) per 100 patient years are presented. ACR responses are presented on an intent-to-treat basis using non-responder imputation up to week 52.

Results

From week 24 up to 156 (with 228 patient years of ixekizumab exposure), 140 [61.3 IR] and 15 (6.6 IR) patients reported infections and serious adverse events, respectively. Serious adverse events included one death and four serious infections. In all patients initially treated with IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W at week 0 (non-responder imputation), ACR20 (61 and 51%), ACR50 (42 and 33%) and ACR70 (26 and 18%) responses persisted out to week 52. Placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab demonstrated efficacy as measured by ACR responses at week 52.

Conclusion

During the extension period, the overall safety profile of ixekizumab remained consistent with that observed with the double-blind period, and clinical improvements persisted up to 1 year.

Keywords: ixekizumab, interleukin-17A, biologic, bDMARDs, psoriatic arthritis, TNF inadequate responders, efficacy, safety, psoriasis, long-term

Rheumatology key messages

Study composed exclusively of patients who had an inadequate response or intolerance to TNF inhibitors.

Continued ixekizumab treatment had a safety profile consistent with that observed during the double-blind period.

Ixekizumab provided rapid improvements in the signs and symptoms of PsA that persisted up to 1 year.

Introduction

PsA is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease with multiple manifestations including peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis and psoriasis [1]. For patients receiving biologic treatment, TNF inhibitors are most frequently prescribed; however, a significant number of patients with PsA have insufficient efficacy or become intolerant to TNF inhibitor therapy [2]. Thus, therapies with an alternative mechanism of action with demonstrated long-term safety and efficacy are important for this patient population.

IL-17A is a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in the pathophysiology of PsA [3]. Ixekizumab is a high affinity mAb that selectively targets IL-17A [4]. In a 24-week placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (SPIRIT-P2), ixekizumab treatment was superior to placebo in improving disease activity, physical function and patient-reported quality of life of patients with active PsA who had had a previous inadequate response to TNF inhibitor therapy [5].

Herein, we report the accumulated safety findings (weeks 24 up to 156) and efficacy data (weeks 24–52) of ixekizumab treatment during the extension period of SPIRIT-P2 (weeks 24–156).

Methods

Trial design

SPIRIT-P2 (NCT02349295; EudraCT 2011-002328-42) is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial in patients with active PsA and a previous inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. Detailed methodology of the double-blind treatment period (weeks 0–24) has been published [5]. Briefly, patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to subcutaneous administration of placebo or 80 mg ixekizumab either every 4 weeks (IXEQ4W) or every 2 weeks (IXEQ2W) following a 160-mg starting dose at week 0 (supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). At week 16, inadequate responders (defined by blinded, predefined criteria of <20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts) were required to add or modify concomitant medications. Inadequate responders remained on their originally assigned ixekizumab dose or if receiving placebo, were re-randomized (1:1) to IXEQ4W or IXEQ2W following a 160-mg starting dose.

At the start of the extension period (weeks 24–156), any patients on placebo were re-randomized (1:1) to IXEQ2W or IXEQ4W following a 160-mg starting dose. Patients assigned an ixekizumab dose prior to week 24 remained on their dose throughout the extension period. Treatment remained blinded to investigators, trial site personnel and patients until all patients had completed the double-blind treatment period or had discontinued from the trial prior to week 24. During the extension period, concomitant medication could be added, modified or withdrawn. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients were discontinued from study treatment for lack of efficacy if they failed to demonstrate ⩾20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts.

The database lock was performed after all patients completed the week 52 visit or discontinued prior to week 52. This report summarizes all safety analyses for the ongoing extension period (up to week 156) at the time of database lock. Efficacy analyses are summarized up to and including the week 52 visit.

The trial was done in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol was approved by central or locally appointed ethics committees for all investigator sites. Patients provided written informed consent before the study-related procedures were undertaken.

Patients

Detailed patient eligibility criteria have been published [5]. Briefly, enrolled patients were ⩾18 years of age, fulfilled the Classification Criteria for PsA [6], had three or more of 68 tender joint and three or more of 66 swollen joint counts, and had active or document history of plaque psoriasis. Enrolment was limited to patients who were previously treated with TNF inhibitors and had an inadequate response to one or two TNF inhibitors or were intolerant to TNF inhibitors.

Assessments

Safety evaluations included the assessment of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs), vital signs, physical examination findings, laboratory studies and immunogenicity. AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, represented herein by Preferred Terms. Reductions in neutrophils from normal levels were defined by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events using a lower limit of normal for neutrophils of 2.0 × 109 cells/l.

Pre-defined efficacy endpoints assessed up to week 52 include the proportion of patients achieving at least ACR20/ACR50/ACR70 [7]; the proportion of patients achieving at least 75/90/100% improvements in baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores (PASI75/PASI90/PASI100) [8]; the proportion of patients achieving a minimal disease activity (MDA), defined as fulfilling at least five of the following seven criteria: tender joint count ⩽1, swollen joint count ⩽1, PASI ⩽1 or body surface area (BSA) ⩽3, Patient’s Assessment of Pain visual analogue score ⩽15, Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity visual analogue score ⩽20, HAQ-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) ⩽0.5 and tender entheseal points ⩽1 [9,10]. Patients fulfilling all seven criteria have achieved very low disease activity; change from baseline in the HAQ-DI [11]; proportion of patients reaching the minimally clinically important difference in the HAQ-DI (0.35) [12]; the change from baseline in 28-joint DAS using CRP (DAS28-CRP) [13]; the change from baseline in Short Form (36 items) Health Survey (SF-36) Physical and Mental Component Summary scores [14]; and the proportion of patients achieving a score of 0 on the static Physician Global Assessment of psoriasis. As a post hoc assessment, the change from baseline in disease activity in PsA (DAPSA) as well as patients achieving low disease activity (DAPSA score ⩽14) and remission (DAPSA score ⩽4) were analysed [15,16].

Additional pre-defined secondary endpoints for patients affected at baseline were enthesitis [Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI)] [17], dactylitis [Leeds Dactylitis Index-Basic (LDI-B)] [18] and a modified version of the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index [19], which assessed fingernails only. Efficacy variables were assessed at each visit during the extension period (weeks 28, 32, 36, 44 and 52) with the exception of LEI, LDI-B and Nail Psoriasis Severity Index, which were assessed only at weeks 32, 44 and 52.

Statistical analysis

Safety analyses were conducted using the extension period population (EPP) defined as all patients who entered and received one or more doses of study medication during the extension period (weeks 24–156). Week 24 was baseline for safety assessments. Safety analyses from the double-blind period (week 0–24) are also summarized for patients who were initially randomized to and received at least one dose of study medication. Efficacy analyses were performed on the EPP (pre-specified) and the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (ad hoc), defined as all randomized patients. Efficacy and safety analyses of the EPP were summarized according to four treatment groups: PBO/IXEQ2W, PBO/IXEQ4W, IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W. The PBO/IXE groups include patients who were randomized to IXE at week 16 (inadequate responders) or week 24.

There were no treatment group comparisons in any analysis. For patients classified as inadequate responders at week 16, safety and efficacy data after week 16 up to week 24 were not included. All safety and efficacy data, regardless of inadequate responder status of the patient, were included after week 24. Safety data are presented as frequencies or exposure-adjusted incidence rates (IRs; number of unique patients with events/total patient years × 100). For all categorical efficacy measures, missing data were imputed using either non-responder imputation (NRI) or multiple imputation (MI). In the MI analyses, partial imputation of non-monotone missing data was applied using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method with the simple imputation model, followed by a sequential regression imputation with the baseline score. In an ad hoc analysis, NRI was used for analyses of maintained response [response rates from weeks 24 to 52 among EPP patients who already had a designated response at week 24 (i.e. ACR20/ACR50/ACR70)]. For continuous efficacy measures, all week 52 data were imputed using MI or modified baseline observation carried forward (mBOCF).

Results

Patient disposition

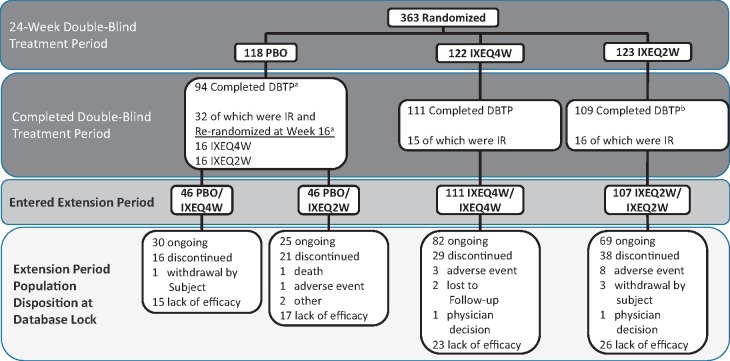

Of 363 patients randomized, 310 (85%) completed the double-blind treatment period and entered the extension period (Fig. 1). Per study design, patients who failed to demonstrate a pre-defined level of efficacy during the extension period (i.e. ⩾20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts at any visit at or after week 32) were discontinued from the trial; the majority of patients [n = 223 (61% of randomized patients; 72% of EPP)] completed week 52 of treatment. At the time of this analysis, 206 patients (57% of randomized patients; 66% of EPP) remained in the trial. Of these patients, discontinuation due to a ‘lack of efficacy’ was the most common reason for patient discontinuation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition of the SPIRIT-P2 extension period population

Detailed data from the double-blind period have been published [5]. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits, patients were discontinued from study treatment for lack of efficacy if they failed to demonstrate ≥20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts. aTwo randomized PBO patients completed the DBTP but did not enter the extension period. bTwo randomized IXEQ2W patients completed the DBTP but did not enter the extension period. DBTP: double-blind treatment period; IR: inadequate responders; IXE: ixekizumab; PBO: placebo; Q2W: 80 mg every 2 weeks; Q4W: 80 mg every 4 weeks.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the ITT population have been previously published [5]. For patients who entered the extension period, baseline (week 0) demographics and clinical characteristics were well balanced among the four treatment groups (Table 1). The mean age was 51.8 years with the majority of patients being white (92%) and female (53%). Based on Moll and Wright [20] classification and as reported by the investigators, 84% of patients had polyarthritis, 10% asymmetrical oligoarthritis, 3% distal interphalangeal predominant PsA, 2% spondylitis and 1% arthritis mutilans. Investigators were limited to selecting only one classification; thus patients may have exhibited other features of PsA. Most patients were receiving concomitant conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs) (53%) at week 0, with 91% of these patients taking MTX. Among the EPP, 55% of patients had had an inadequate response to one TNF inhibitor, 36% had a prior inadequate response to two TNF inhibitors and 9% had intolerance to a TNF inhibitor. Seventy-five per cent of patients had enthesitis, 24% had dactylitis, 64% had plaque psoriasis with ⩾3% BSA and 65% had fingernail psoriasis.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics (extension period population)

| Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics | PBO/IXEQ4W (n = 46) | PBO/IXEQ2W (n = 46) | IXEQ4W/ IXEQ4W (n = 111) | IXEQ2W/ IXEQ2W (n = 107) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 51.0 (9.2) | 52.4 (10.8) | 51.6 (13.6) | 52.1 (11.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (43.5) | 24 (52.2) | 56 (50.5) | 46 (43.0) |

| Weight, mean (s.d.), kg | 96.1 (24.0) | 91.5 (21.7) | 91.0 (22.5) | 85.8 (20.8) |

| BMI, mean (s.d.), kg/m2 | 33.5 (8.2) | 31.0 (7.6) | 31.2 (7.3) | 30.1 (6.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 44 (95.7) | 41 (89.1) | 101 (91.0) | 97 (91.5) |

| Asian | 1 (2.2) | 3 (6.5) | 7 (6.3) | 7 (6.6) |

| Other | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (2.7) | 2 (1.9) |

| Time since PsA diagnosis, mean (s.d.), years | 9.7 (9.0) | 8.0 (5.7) | 10.9 (10.0) | 10.1 (7.3) |

| Time since psoriasis diagnosis, mean (s.d.), years | 13.5 (11.0) | 16.3 (14.3) | 16.0 (12.7) | 16.4 (12.4) |

| cDMARD current use, n (%) | 24 (52.2) | 19 (41.3) | 56 (50.5) | 65 (60.7) |

| MTX current use, n (%) | 16 (34.8) | 17 (37.0) | 46 (41.4) | 54 (50.5) |

| Prior TNFi experience, n (%) | ||||

| Inadequate response to 1 TNFi | 26 (56.5) | 25 (54.3) | 62 (55.9) | 56 (52.3) |

| Inadequate response to 2 TNFi | 17 (37.0) | 15 (32.6) | 41 (36.9) | 40 (37.4) |

| Intolerance to a TNFia | 3 (6.5) | 6 (13.0) | 8 (7.2) | 11 (10.3) |

| Patients with specific disease characteristics, n (%) | ||||

| Current psoriasisb | 42 (91.3) | 41 (89.1) | 108 (97.3) | 97 (90.7) |

| Psoriasis BSA ≥3%c | 25 (61.0) | 31 (75.6) | 62 (61.4) | 57 (62.0) |

| Fingernail psoriasisb | 29 (64.4) | 25 (54.3) | 81 (73.0) | 67 (62.6) |

| Dactylitisd | 7 (15.2) | 6 (13.0) | 26 (23.4) | 16 (15.0) |

| Enthesitise | 24 (52.2) | 29 (63.0) | 61 (55.0) | 73 (68.2) |

| Disease and quality of life characteristics, mean (s.d.) | ||||

| Tender joint count (68 joints) | 27.2 (17.6) | 19.9 (14.0) | 21.3 (14.1) | 25.0 (16.8) |

| Swollen joint count (66 joints) | 12.0 (9.0) | 9.0 (5.6) | 12.4 (10.3) | 13.6 (11.5) |

| Patient-reported joint pain, 0–100 | 65.7 (17.9) | 62.7 (22.5) | 62.4 (21.2) | 62.6 (21.1) |

| Physician global assessment, 0–100 | 59.0 (21.8) | 61.5 (18.1) | 59.3 (21.6) | 64.4 (17.0) |

| Patient global assessment, 0–100 | 67.2 (19.3) | 60.1 (23.3) | 66.5 (20.4) | 65.4 (20.9) |

| CRP, mg/l | 15.9 (23.5) | 10.1 (18.7) | 16.9 (28.5) | 12.6 (25.5) |

| HAQ-DI | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) |

| SF-36 PCS score | 31.4 (9.0) | 31.7 (9.5) | 32.5 (9.7) | 32.2 (9.4) |

| SF-36 MCS score | 48.5 (12.8) | 44.5 (15.7) | 48.7 (12.6) | 47.9 (12.9) |

| DAS28-CRP | 5.3 (1.2) | 4.7 (0.8) | 5.0 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.2) |

| DAPSA | 53.6 (26.1) | 42.6 (17.0) | 49.0 (22.0) | 53.2 (27.9) |

| LDI-Bd | 45.7 (30.8) | 30.2 (17.3) | 29.5 (34.2) | 53.9 (38.8) |

| LEIe | 3.1 (1.8) | 2.7 (1.5) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.7) |

| PASI total scorec | 5.0 (7.2) | 5.5 (5.8) | 6.4 (8.2) | 6.1 (8.7) |

| PASI total score (BSA ≥3%) | 7.6 (8.5) | 6.5 (6.3) | 9.4 (9.5) | 8.7 (10.3) |

| NAPSIf | 17.9 (17.9) | 19.8 (17.1) | 20.8 (20.6) | 20.3 (20.2) |

| % BSA involvedc | 9.5 (13.5) | 11.2 (14.4) | 12.5 (17.8) | 11.4 (18.8) |

Patients previously received a TNFi and had discontinued.

Qualitatively assessed by the investigator at baseline.

Patients with baseline plaque psoriasis.

LDI-B > 0.

LEI > 0.

Baseline fingernail psoriasis present. cDMARD: conventional DMARD; DAPSA: Disease Activity in PsA; DAS28-CRP: 28-joint DAS using CRP; HAQ-DI: HAQ-Disability Index; IXE: ixekizumab; LDI-B: Leeds Dactylitis Index-Basic; LEI: Leeds Enthesitis Index; MCS: Mental Component Summary; NAPSI: Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PCS: Physical Component Summary; Q2W: 80 mg every 2 weeks; Q4W: 80 mg every 4 weeks; SF-36: Short Form (36 Items) Health Survey; TNFi: TNF inhibitor.

Safety

Extension period (weeks 24–156; EPP)

Mean (s.d.) ixekizumab treatment exposure during the extension period (excluding time during the double-blind treatment period) was 269.0 (141.4) days. Patient years of ixekizumab exposure was 228.3. Overall 66% of patients had at least one treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) with a 90.2 incidence rate (IR), occurring at similar percentages and IRs among the treatment groups (Table 2). One patient (in the PBO/IXEQ2W treatment group) died 502 days after starting ixekizumab treatment (reported as a cardiorespiratory arrest); independent external adjudication concluded that myocardial infarction was the cause of death. The investigator considered the event not related to the study drug. There were no reports of suicide or suicidal ideation in the EPP. Twelve patients discontinued treatment due to an AE (including death): two patients in the PBO/IXEQ2W treatment group (one each of hepatic cirrhosis and cardiorespiratory arrest), two patients in the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W treatment group (one each of papillary thyroid cancer and breast tenderness) and eight patients in the IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment group [one each of injection-related reaction (generalized urticaria), procedural pain, cholesteatoma, diarrhoea, myalgia, cerebrovascular accident, renal failure and rash]. Serious AEs were reported in 4% (6.0 IR) of PBO/IXEQ4W patients, 7% (10.2 IR) of PBO/IXEQ2W patients, 5% (6.8 IR) of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W patients and 4% (5.1 IR) of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients. The most frequent TEAEs (defined as ⩾2% of all extension period patients) were upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, injection site reaction, sinusitis, urinary tract infection, bronchitis, tonsillitis and pharyngitis. The majority of TEAEs were rated by the investigator as mild or moderate in severity; 5% (7.4 IR) of TEAEs were rated severe.

Table 2.

Safety overview

| Extension period population (weeks 24–156) | DBP population (weeks 0–24) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO/IXEQ4W | PBO/IXEQ2W | IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W | IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W | IXEQ4W (n = 122) | IXEQ2W (n = 123) | ||||||

| n = 46 | PY = 33.4 | n = 46 | PY = 29.5 | n = 111 | PY = 87.7 | n = 107 | PY = 77.8 | PY = 52.4 | PY = 50.9 | ||

| Adverse events | % | IR | % | IR | % | IR | % | IR | IR | IR | |

| TEAEs | 69.6 | 95.9 | 58.7 | 91.5 | 71.2 | 90.1 | 63.6 | 87.4 | 158.5 | 177.0 | |

| Mild | 23.9 | 33.0 | 23.9 | 37.3 | 36.9 | 46.8 | 25.2 | 34.7 | 91.7 | 84.6 | |

| Moderate | 41.3 | 56.9 | 26.1 | 40.7 | 29.7 | 37.6 | 32.7 | 45.0 | 59.2 | 74.7 | |

| Severe | 4.3 | 6.0 | 8.7 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 17.7 | |

| Most frequent TEAEsa | |||||||||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 13.0 | 18.0 | 6.5 | 10.2 | 8.1 | 10.3 | 15.0 | 20.6 | 21.0 | 23.6 | |

| Nasopharyngitis | 4.3 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 12.5 | 8.4 | 11.6 | 15.3 | 7.9 | |

| Injection site reaction | 8.7 | 12.0 | 8.7 | 13.6 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 5.6 | 7.7 | 15.3 | 29.5 | |

| Sinusitis | 8.7 | 12.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 13.4 | 9.8 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 8.7 | 12.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 11.5 | 7.9 | |

| Bronchitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 7.9 | |

| Tonsillitis | 4.3 | 6.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 7.6 | 0 | |

| Pharyngitis | 2.2 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 5.9 | |

| Diarrhoea | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 9.6 | 9.8 | |

| Serious adverse events | 4.3 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 10.2 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 15.7 | |

| Serious infections | 2.2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0 | 5.9 | |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Discontinued due to adverse event | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 7.5 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 15.7 | |

| Adverse events of special interestb | |||||||||||

| Infections | 50.0 | 68.9 | 34.8 | 54.2 | 48.6 | 61.6 | 43.9 | 60.4 | 89.8 | 92.4 | |

| Cytopenias | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Injection-site reactionsc | 13.0 | 18.0 | 13.0 | 20.3 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 8.4 | 11.6 | 26.7 | 57.0 | |

| Hepatic event | 4.3 | 6.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 9.8 | |

| Allergic reaction/hypersensitivities | 4.3 | 6.0 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 9.0 | 24.8 | 27.5 | |

| Cerebro-cardiovascular eventsd | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Depression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 3.9 | |

| Interstitial lung diseasee | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9e | 1.3e | 0 | 0 | |

| Malignancies | 2.2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 0 | |

The same patient could report more than one event.

Listed according to MedDRA (V.19.0) preferred term, occurring in ≥2% of all extension period population.

Adverse events of special interest not reported include Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Includes all terms for reactions at the injection site including, but not limited to, reaction, erythema and pain.

Events were adjudicated.

Incidental finding during an X-ray; patient was asymptomatic. DBP: double-blind period. IR: exposure-adjusted incidence rate; IXE: ixekizumamb; PBO: placebo; PY: patient year; Q2W: 80 mg every 2 weeks; Q4W: 80 mg every 4 weeks; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

Overall 45% of patients reported at least one treatment-emergent infection with a 61.3 IR. Infections were reported at similar percentages and IRs across the treatment groups, and most infections were rated as mild or moderate in severity. Four patients reported serious infections: one patient in the PBO/IXEQ4W treatment group (diverticulitis), two patients in the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W treatment group (latent tuberculosis and lower respiratory tract infection) and one patient in the IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment group (oesophageal candidiasis). The patient with an SAE of latent tuberculosis tested positive at the protocol-required week 52 visit with a T-Spot test. The patient was electively hospitalized for diagnostic testing including a CT scan, bronchoscopy and culture for mycobacteria, and the results showed no evidence of active tuberculosis. No patients discontinued treatment due to an infection-related AE. There were 11 patients who had mucocutaneous Candida infections (i.e. five oral, four vaginal, one male genital and one with an SAE of oesophageal candidiasis), none of which resulted in treatment discontinuation. Two patients had herpes zoster, one mild and one moderate. There were no cases of active tuberculosis, hepatitis B or C reactivation, invasive Candida, endemic or other invasive fungal infections. Laboratory testing showed that among patients with normal baseline neutrophil counts, transient treatment emergent grade 2 (<1500–1000 cells/mm3) neutropenia occurred in three patients, and there were no cases of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia. No patient had an infection within 14 days of grade 2 neutropenia.

Injection site reactions were reported in 8% (11.4 IR) of patients during the extension period. Numerically higher frequencies and IRs were present in patients initially randomized to placebo. Most injection site reactions were mild, and no patients discontinued treatment due to injection site reactions. Hypersensitivity events were reported in 4% (5.7 IR) of patients, all mild or moderate in severity and non-serious; there were no reports of anaphylaxis. Four patients had a cerebrocardiovascular event confirmed by adjudication: one patient in the PBO/IXEQ2W treatment group (cardiorespiratory arrest) and three patients in the IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatments group (coronary artery thrombosis, cerebrovascular accident and haemorrhagic stroke). Two patients discontinued the trial due to cerebrocardiovascular events (one cardiorespiratory arrest and one cerebrovascular accident). Malignancies, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, were reported in one patient (IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W): a papillary thyroid cancer, which led to study discontinuation. One patient (PBO/IXEQ4W) had basal cell carcinoma and Bowen’s disease. No patient reported a TEAE of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Double-blind period (weeks 0–24)

Incidence rates of all patients who were initially randomized to ixekizumab during the double-blind period are presented in Table 2. For patients in the double-blind and extension periods, respectively, the IRs were 167.6 and 90.2 for patients having at least one TEAE, 10.7 and 6.6 for SAEs, and 12.6 and 5.3 for discontinuations due to AE.

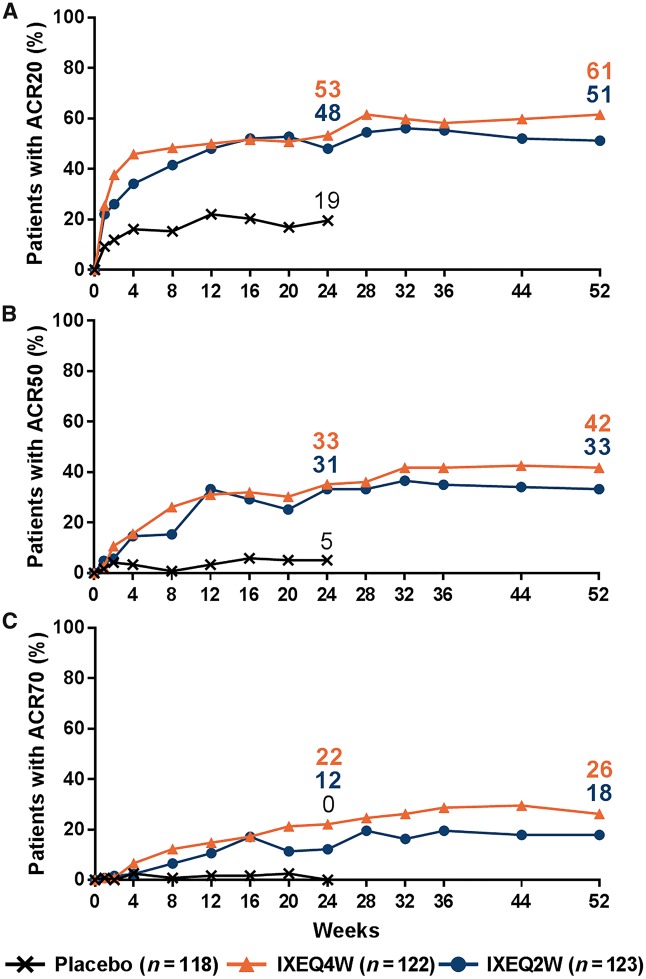

Efficacy

All efficacy endpoints for the ITT population at week 52 are summarized in Table 3. In the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment groups, the proportion of patients achieving ACR20 (61 and 51%), ACR50 (42 and 33%) and ACR70 (26 and 18%) responses persisted out to week 52 in the ITT population (Fig. 2; NRI). At week 52, placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab also demonstrated relatively high ACR responses [supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online; EPP (NRI analysis)]. Among ITT patients who achieved ACR20, ACR50 or ACR70 at week 24, the majority maintained their respective responses out to week 52: 84, 84 and 78% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W patients and 79, 73 and 73% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients, respectively (NRI analysis).

Table 3.

Week 52 efficacy overview (intent-to-treat population)

| Efficacy outcomes | Ixekizumab Q4W (N = 122) | Ixekizumab Q2W (N = 123) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responder rate [n/N (%)] | NRI | MI | NRI | MI |

| ACR20 | 75/122 (61.5) | 100/122 (83.6) | 63/123 (51.2) | 92/123 (75.4) |

| ACR50 | 51/122 (41.8) | 64/122 (53.4) | 41/123 (33.3) | 50/123 (40.6) |

| ACR70 | 32/122 (26.2) | 38/122 (31.6) | 22/123 (17.9) | 24/123 (20.4) |

| HAQ-DI MCIDa | 48/104 (46.2) | 63/104 (60.9) | 38/108 (35.2) | 58/108 (53.8) |

| Minimal disease activity | 42/122 (34.4) | 46/122 (37.6) | 29/123 (23.6) | 35/123 (28.7) |

| Low disease activityb | 65/122 (53.3) | 78/122 (64.0) | 46/123 (37.4) | 58/123 (47.4) |

| Remissionc | 23/122 (18.9) | 25/122 (20.3) | 14/123 (11.4) | 15/123 (12.0) |

| LDI-B = 0d | 21/28 (75.0) | 22/28 (81.4) | 11/20 (55.0) | 13/20 (68.5) |

| LEI = 0e | 32/68 (47.1) | 44/68 (64.5) | 30/84 (35.7) | 45/84 (53.4) |

| PASI75f | 41/68 (60.3) | 55/68 (81.3) | 37/68 (54.4) | 57/68 (83.1) |

| PASI90f | 34/68 (50.0) | 45/68 (65.8) | 27/68 (39.7) | 42/68 (61.8) |

| PASI100f | 27/68 (39.7) | 35/68 (52.1) | 24/68 (35.3) | 35/68 (52.0) |

| sPGA (0)g | 26/60 (43.3) | 33/60 (54.7) | 27/62 (43.5) | 36/62 (58.3) |

| NAPSI (0)h | 41/89 (46.1) | 53/89 (59.1) | 24/74 (32.4) | 35/74 (47.5) |

| Mean change from baseline | mBOCF (s.d.) | MI (s.e.) | mBOCF (s.d.) | MI (s.e.) |

| DAS28-CRP | −2.6 (1.3) | −2.5 (0.1) | −2.3 (1.1) | −2.0 (0.1) |

| DAPSAi | −30.9 (27.6) | −36.6 (2.0) | −31.2 (26.4) | −35.7 (2.4) |

| HAQ-DI | −0.4 (0.5) | −0.5 (<0.1) | −0.4 (0.5) | −0.4 (0.1) |

| SF-36 PCS Score | 7.4 (8.9) | 7.6 (0.8) | 7.1 (10.0) | 7.6 (0.9) |

| SF-36 MCS Score | 4.1 (11.1) | 4.5 (1.0) | 3.4 (9.4) | 3.6 (1.0) |

| LDI-Bd | −29.1 (34.5) | −24.4 (4.0) | −50.7 (32.9) | −46.1 (7.9) |

| LEIe | −1.8 (1.9) | −2.0 (0.2) | −1.6 (2.1) | −2.0 (0.2) |

| NAPSIh | −15.2 (19.7) | −15.7 (2.1) | −14.4 (19.0) | −16.7 (2.5) |

Baseline HAQ-DI score ≥0.35.

≤14 DAPSA score.

≤4 DAPSA score.

Baseline LDI-B > 0.

Baseline LEI > 0.

Baseline body surface area ≥3%.

Baseline sPGA ≥ 3.

Baseline fingernail psoriasis present.

Baseline mean DAPSA scores were 49.6 (IXEQ4W) and 52.9 (IXEQ2W). DAPSA: Disease Activity in PsA; DAS-28-CRP: 28-joint DAS using CRP; HAQ-DI: HAQ-Disability Index; LDI-B: Leeds Dactylitis Index-Basic; LEI: Leeds Enthesitis Index; mBOCF: modified baseline observation carried forward; MCID: minimal clinically important difference; MCS/PCS: mental or physical component summary; MI: multiple imputation; NAPSI: Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NRI: non-responder imputation; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q4W/Q2W: 80 mg every 4 or 2 weeks; SF-36: Short Form (36 Items) Health Survey; sPGA: static physician global assessment of psoriasis.

Fig. 2.

ACR responses up to week 52

Intent-to-treat populations. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients were discontinued from study treatment if they failed to demonstrate ≥20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts. Missing data were imputed with NRI. IXE: ixekizumab; NRI: non-responder imputation; PBO: placebo; Q2W: 80 mg every 2 weeks; Q4W: 80 mg every 4 weeks.

At week 52 in the ITT population (mBOCF analysis), improvements in disease activity, as measured by mean (s.d.) change from baseline DAS28-CRP, were –2.6 (1.3) and –2.3 (1.1) for the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment groups, respectively. At week 52, 34 and 24% of patients achieved MDA in the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment groups, respectively (NRI analysis). Of patients achieving MDA at week 52, 36% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and 28% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients achieved very low disease activity. As measured by DAPSA, 53% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and 37% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients achieved low disease activity and 19% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and 11% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients achieved remission. Placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab also demonstrated improvements in measures of disease activity [supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online; EPP (NRI analysis)].

At week 52 in the ITT population (mBOCF analysis), improvements in physical function, as measured by mean (s.d.) change from baseline HAQ-DI, were −0.4 (0.5) and −0.4 (0.5) for the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment groups, respectively. At week 52, 46 and 35% of patients met or exceeded HAQ-DI minimally clinically important difference in the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment groups, respectively (NRI analysis). At week 52, improvements from baseline SF-36 component summary scores were demonstrated in the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W (physical: 7.4; mental: 4.1) and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W (physical: 7.1; mental: 3.4) treatment groups (mBOCF analysis). For patients with baseline dactylitis (LDI-B > 0), 75% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and 55% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients had dactylitis resolution at week 52 (NRI analysis). For patients with baseline enthesitis (LEI > 0), 47% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and 36% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients had enthesitis resolution at week 52. Placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab also demonstrated improvements on various additional patient-reported outcomes and efficacy measures at week 52 [supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online; EPP (NRI or mBOCF analyses)].

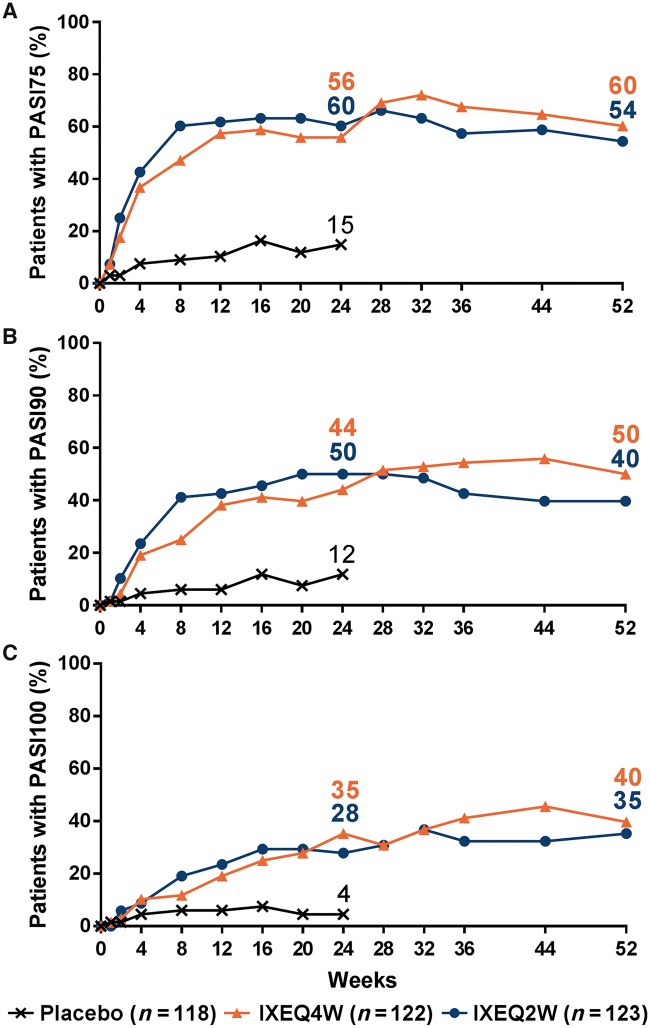

In the IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W treatment groups with plaque psoriasis ⩾3% BSA at baseline, the proportion of patients achieving PASI75 (60 and 54%), PASI90 (50 and 40%) and PASI100 (40 and 35%) responses persisted out to week 52 in the ITT population (Fig. 3; NRI analysis). For ITT patients with baseline fingernail psoriasis, 46% of IXEQ4W/IXEQ4W and 32% of IXEQ2W/IXEQ2W patients had resolution of nail psoriasis at week 52. At week 52, placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab also demonstrated relatively high PASI responses and resolution of nail psoriasis [supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online; EPP (NRI analysis)].

Fig. 3.

PASI responses up to week 52

Intent-to-treat populations. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients were discontinued from study treatment if they failed to demonstrate ≥20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts. Missing data were imputed with NRI. IXE: ixekizumab; NRI: non-responder imputation; PASI75/90/100: 75%/90%/100% improvement from baseline on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBO: placebo; Q2W: 80 mg every 2 weeks; Q4W: 80 mg every 4 weeks.

From weeks 0 to 52 in patients receiving at least one dose of ixekizumab, treatment-emergent anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) were identified in 26 patients (8%). Most patients had low titres (88%), and nine patients had detectable neutralizing antibodies. In the EPP, 18 patients were identified with treatment-emergent ADAs. For these patients, ACR20 response rates at week 52 were 78% (NRI analysis). For all patients who had observable treatment-emergent ADAs (weeks 0–52), there was no apparent association between the development of treatment-emergent ADA and injection site reactions or hypersensitivity events.

Discussion

In this report, the safety profile of ixekizumab treatment was generally consistent with published findings in patients with active PsA or moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis receiving ixekizumab [5,21–23]. During the extension period, continued ixekizumab treatment did not result in increased rates of overall AE relative to the double-blind period. Treatment-emergent infections, injection site reactions and hypersensitive events were reported in higher numbers of ixekizumab-treated patients than placebo during the double-blind period [5]; however, the IRs of these AEs were relatively lower during the extension period. Therapies targeting the IL-17 pathway have been associated with neutropenia and Candidiasis in patients with PsA [22,24,25]. In this study, grades 1 and 2 neutropenia were reported with no reports of grade 3 or higher. Neutropenias were transient, and no patients had an infection within 2 weeks of a grade 2 neutropenia. Ixekizumab treatment was associated with Candida infections, but infections were not invasive and did not lead to discontinuation. There were no reports of active or reactivated tuberculosis. No cases of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease were reported; patients with a history of, but not active, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis were permitted in this trial.

In patients who had an inadequate response or were intolerant to TNF inhibitors, treatment with ixekizumab, whether administered every 2 or 4 weeks, had improvements in the signs and symptoms of PsA that persisted over 52 weeks. The majority of patients who achieved an ACR response by week 24 maintained their ACR response up to week 52. Ixekizumab treatment was also associated with improvements in patient-reported physical and mental outcomes, dactylitis, enthesitis, and plaque psoriasis. Treat-to-target goals (i.e. MDA and remission as measured by DAPSA) were achieved in some patients treated with ixekizumab out to week 52. Placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab treatment demonstrated comparable efficacy at week 52 in joint and skin endpoints.

When analysing patients on IXE monotherapy or IXE with concomitant cDMARDs, a significantly higher proportion achieved ACR20 responses than placebo-treated patients at week 24 [5]. Because all patients could modify, add or withdraw their concomitant medication during the extension period, these findings were not extended up to week 52.

While this clinical trial was not powered to detect statistical differences between ixekizumab treatment arms, there was no apparent increased benefit with IXEQ2W relative to IXEQ4W in arthritis-related measures. While unexpected, dose-ranging studies in arthritis clinical trials have previously demonstrated that increased dose frequency does not necessarily result in improved therapeutic benefits [26].

The results from the 24-week double-blind treatment period and extension period of SPIRIT-P2 are consistent with observations from SPIRIT-P1, a phase 3 trial investigating ixekizumab treatment in patients with active PsA who had previously not received biologic therapy for either PsA or psoriasis [21,22]. Treatment guidelines from the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and PsA (GRAPPA) place non-TNF inhibitor biologics (e.g. IL-17A antagonists) as first line biologics alongside TNF inhibitors or after initial TNF inhibitor use [27], whereas the recommendation from EULAR place non-TNF inhibitor biologics for PsA only after initial TNF inhibitor use [28]. Collectively, the findings from both SPIRIT trials indicate that ixekizumab is a potential treatment option for patients with active PsA, regardless of whether they are naïve to biologic therapy or had previously failed on TNF inhibitor therapy, in line with either GRAPPA or EULAR treatment guidelines.

There are inherent limitations for the extension period of this trial. There was no placebo or active control in the extension period. Treatment was open label once all patients had completed the double-blind treatment period or had discontinued from the trial before the end of that period. The numbers of patients switching from placebo to ixekizumab treatment were small. This trial did not include an assessment of radiographic progression, the inhibition of which has been shown previously with ixekizumab [21,22].

In conclusion, the safety profile was consistent with other ixekizumab studies involving patients with PsA or moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Treatment with either IXEQ4W or IXEQ2W demonstrated efficacy for up to 52 weeks in key clinical domains of PsA. Overall, these findings support IL-17A antagonism with ixekizumab treatment in patients with active PsA and previous inadequate response to TNF inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Matthew M. Hufford, an employee of Eli Lilly and Company, for his writing support. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the investigators of SPIRIT-P2.

Funding: Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA) supported this study.

Disclosure statement: M.C.G. is a consultant for and has received funding from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Galapagos, Gilead and Pfizer. B.C. is on the speaker’s bureau of AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai and Union Chimique Belge (UCB) and has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer and Roche-Chugai. T.-F.T. has conducted clinical trials or received honoraria for serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline-Stiefel, Janssen-Cilag, LeoPharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and Serono International SA (now Merck Serono Intenational). F.B. is a consultant, advisory board member, and member of the speaker’s bureau for Eli Lilly and Company. D.H.A. and L.K. are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. C.L. is a former employee of Eli Lilly and Company, is currently employed by Genentech, Inc. and is a shareholder of Eli Lilly and Company. P.N. has received research funding for clinical trials and honoraria for lectures and advice from Eli Lilly and Company.

References

- 1. Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD.. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2095–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mease P. A short history of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33 (5 Suppl 93):S104–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chiricozzi A. Pathogenic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2014;105 (Suppl 1):9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu L, Lu J, Allan BW. et al. Generation and characterization of ixekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that neutralizes interleukin-17A. J Inflamm Res 2016;9:39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M. et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:2317–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P. et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M. et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feldman SR, Krueger GG.. Psoriasis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64 (Suppl 2):ii65–8, discussion ii9–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS.. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coates LC, Helliwell PS.. Validation of minimal disease activity criteria for psoriatic arthritis using interventional trial data. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:965–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY.. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol 1982;9:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mease PJ, Woolley JM, Bitman B. et al. Minimally important difference of Health Assessment Questionnaire in psoriatic arthritis: relating thresholds of improvement in functional ability to patient-rated importance and satisfaction. J Rheumatol 2011;38:2461–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells G, Becker JC, Teng J. et al. Validation of the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:954–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Husted JA, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Long JA, Cook RJ.. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 1997;24:511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schoels M, Aletaha D, Funovits J. et al. Application of the DAREA/DAPSA score for assessment of disease activity in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoels MM, Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS.. Disease activity in psoriatic arthritis (PsA): defining remission and treatment success using the DAPSA score. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:811–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Healy PJ, Helliwell PS.. Measuring clinical enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis: assessment of existing measures and development of an instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:686–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Helliwell PS, Firth J, Ibrahim GH. et al. Development of an assessment tool for dactylitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:1745–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rich P, Scher RK.. Nail Psoriasis Severity Index: a useful tool for evaluation of nail psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moll JM, Wright V.. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1973;3:55–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Heijde D, Dafna DG, Kishimoto M. et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from a phase III study (SPIRIT-P1). J Rheumatol 2018;45:367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT. et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strober B, Leonardi C, Papp KA. et al. Short- and long-term safety outcomes with ixekizumab from 7 clinical trials in psoriasis: etanercept comparisons and integrated data. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:432–40.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B. et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015;386:1137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mease PJ, Genovese MC, Greenwald MW. et al. Brodalumab, an anti-IL17RA monoclonal antibody, in psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kay J, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite treatment with methotrexate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:964–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ. et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1060–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S. et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.