Abstract

Decreased central inhibition, possibly related to hearing loss, may contribute to chronic tinnitus. However, many individuals with normal hearing thresholds report tinnitus, suggesting that the percept in this population may arise from sources other than peripheral deafferentation. One measure of inhibition is sensory gating. Sensory gating involves the suppression of non-novel input, and is measured through cortical auditory evoked potential (CAEP) responses to paired stimuli. In typical gating function, amplitude suppression is observed in the second CAEP response when compared to the first CAEP response, illustrating inhibitory activity. Using this measure, we investigated central inhibitory processes in normal hearing young adults with and without mild tinnitus to determine whether inhibition may be a contributing factor to the tinnitus percept. Results showed that gating function was impaired in the tinnitus group, with the CAEP Pa component significantly correlated with tinnitus severity. Further exploratory analyses were conducted to evaluate variability in gating function within the tinnitus group, and findings showed that high CAEP amplitude suppressors demonstrated gating performance comparable to adults without tinnitus, while low amplitude suppressors exhibited atypical gating function.

Key words: Tinnitus, Normal hearing, Sensory gating, Cortical auditory evoked potentials, Inhibition

Introduction

Idiopathic tinnitus, a phantom auditory percept,1 is an auditory disorder that may be induced by peripheral damage (e.g. hearing loss), but is thought to be sustained centrally.2 Although the pathophysiology of tinnitus remains largely unknown, it has been theorized that deafferentation of neural fibers, resulting from cochlear damage, may induce a decrease of inhibition in the central auditory nervous system.3 Decreased central inhibition can lead to increased spontaneous neural firing rate, neural synchrony, and cortical re-organization.1 For example, re-organization in the tonotopic map of the auditory cortex has been observed in hearing loss and tinnitus, possibly due to decreased lateral disinhibition as neurons are no longer stimulated by auditory input in the hearing loss region.1 However, tinnitus has also been reported in adults with clinically normal auditory thresholds.4 It is therefore unclear as to whether a decrease in central inhibition is related to the tinnitus percept in this population, as there is no clinical indication of cochlear damage present as a possible cause.

One way to measure inhibitory function in the central auditory nervous system is through sensory gating. Auditory gating is the ability of the central nervous system to filter out irrelevant information when presented with repetitive stimuli, and involves temporo- frontal, hippocampal, and frontal cortical networks.5,6 Auditory gating operates through inhibitory circuits involving nicotinic receptors, with inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampus responsible for the suppression of pyramidal neuronal firing following initial auditory stimulation.7 Frontal cortex also plays a role in gating, as decreased frontal cortical activation during gating paradigms has been observed in clinical populations.7,8 Along these lines, it has been hypothesized that the fronto-striatal gating mechanism involving inhibitory processes is deficient in tinnitus, incorrectly assigning value to internal auditory signals which should be suppressed.9 Therefore, assessment of gating function in the tinnitus population may reveal aberrant central processes related to the tinnitus percept that have not yet been explored.

Auditory gating is assessed through electroencephalographic (EEG) measurement of cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) in response to paired stimuli presented within a brief time interval.10,11 The average CAEP in response to the second stimulus in the pair (S2) is compared to the average CAEP response to the first stimulus in the pair (S1), and should demonstrate amplitude suppression. Normal inhibitory function is quantified through the calculation of peak component amplitude ratios (e.g. P50 S2/P50 S1) or difference values (e.g. P50 S1-P50 S2).10,11 Larger amplitude ratios (near 1) and smaller amplitude differences (near 0) have been reported as biomarkers of atypical gating in clinical populations.12,13

As tinnitus is a sensory perception theorized to arise from deficits in central inhibition, CAEP amplitude indices of auditory gating may serve to clarify the role of inhibitory processes in adults with normal hearing and tinnitus. Therefore, we investigated auditory gating function in normal hearing adults with and without mild tinnitus, utilizing a CAEP paired-tone paradigm. Tinnitus severity was quantified using the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory,14 and scores were correlated with CAEP amplitude ratio and difference indices to determine a possible relationship between gating deficits and tinnitus severity. A second aim was to investigate the variability of gating performance within the tinnitus group through an exploratory analysis. Previous studies on auditory gating function have demonstrated that stratification of individuals with high and low amplitude suppression reveals information on variability in central inhibitory processes due to underlying differential mechanisms. 15,16 Therefore, individuals in this group were categorized into high and low CAEP amplitude suppression subgroups and amplitude gating indices were statistically compared.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Thirty-three participants aged 18-30 years were enrolled in the study, which took place at the Central Sensory Processes Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin. The study was approved by the University of Texas Institutional Review Board, and written consent was provided by all participants. No neurological diagnoses were reported by participants. Participants were grouped according to tinnitus experience: no tinnitus (NTINN, n = 18) or tinnitus (TINN, n = 15). There was no significant age difference between NTINN (mean age and standard deviation = 20.39 +/-1.79 years, range = 18-23 years) or TINN groups (mean age and standard deviation = 22.07 +/-3.71 years, range = 18-30 years) (U = 166.5, Z = 1.153, P > 0.05).

Audiometry, speech perception and tinnitus assessment

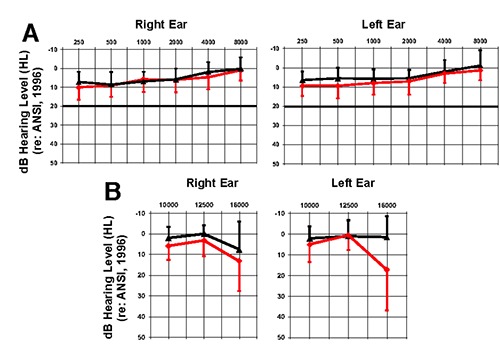

Both NTINN and TINN groups demonstrated clinically normal mean pure tone thresholds (< 20 dB HL) from 250 Hz-8000 Hz via 3M E-A-R TONE™ GOLD 3A insert earphones (Figure 1A). A subset of each group (NTINN, n = 9; TINN, n = 11) participated in extended high-frequency testing (EHF), which was performed using Sennheiser HDA 300 supra-aural headphones. Pure tone thresholds at 10, 12.5, and 16 kHz were assessed to rule out peripheral deafferentation in these non-clinical frequency regions.4 Both groups presented with mean thresholds < 20 dB HL for EHF pure tones (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Mean audiometric thresholds. A) Mean NTINN (n = 18, black) and TINN (n = 15, red) clinical audiometric thresholds in the right and left ears. B) Mean NTINN (n = 9, black) and TINN (n = 11, red) extended high-frequency (EHF) audiometric thresholds in the right and left ears. Positive-going error bars represent one standard deviation for the NTINN group, and negative-going error bars represent one standard deviation for the TINN group.

Auditory cognitive ability was measured using the QuickSIN Speech-in-Noise Test (Etymotic Research). Speech and background noise were presented simultaneously through a speaker at 0° azimuth, with background noise varied from 25 to 0 dB signalto- noise ratio (SNR). The average SNR loss was calculated from two list scores. This measure was performed to determine whether speech perception in background noise differed between the NTINN and TINN groups, as speech perception deficits have been linked to tinnitus and hidden hearing loss, or cochlear synaptopathy, in normal hearing listeners.17

The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), was used to assess tinnitus severity. As seen in Table 1, scores ranged from 0-14, or a severity grade of 1.14 Very mild tinnitus, similar to that observed in these participants, has been reported in previous research,18 and may be due to the young age and normal audiometric profiles of the participants. Participants answered questions on their tinnitus experience, including the duration of tinnitus, whether it was intermittent or chronic, the laterality, and the pitch (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tinnitus participant demographics.

| Subject | Age | Duration | Consistency | Laterality | Pitch | THI Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TINN1 | 28 | 7.5 Years | Intermittent | Bilateral | High | 4 |

| TINN2 | 22 | 2.5 Years | Chronic | Bilateral | High | 8 |

| TINN3 | 25 | No Response | No Response | Bilateral | High | 12 |

| TINN4 | 22 | 4 Years | Chronic | Bilateral | High | 12 |

| TINN5 | 30 | 2 Years | Intermittent | Unilateral | Low | 0 |

| TINN6 | 19 | 8 Years | Intermittent | Bilateral | High | 0 |

| TINN7 | 19 | Entire Life | Intermittent | Unilateral | High | 0 |

| TINN8 | 18 | No Response | No Response | Unilateral | High | 6 |

| TINN9 | 18 | No Response | No Response | Bilateral | High | 8 |

| TINN10 | 19 | No Response | No Response | Bilateral | Low/High | 8 |

| TINN11 | 24 | 3.5 Years | Chronic | Right | High | 10 |

| TINN12 | 24 | Entire Life | Intermittent | Bilateral | High | 0 |

| TINN13 | 25 | 6 Months | Intermittent | Bilateral | Low | 14 |

| TINN14 | 20 | No Response | No Response | Right | High | 0 |

| TINN15 | 19 | 7 Years | Chronic | Bilateral | High | 12 |

Electroencephalography auditory gating paradigm

For the EEG recording session, participants were fit with a 128-channel electrode net (Electrical Geodesics, Inc.) and seated in a reclining chair located in an electromagnetically shielded sound booth. Ocular artifacts were recorded through designated eye electrodes for offline rejection. The sampling rate for the EEG recordings was 1000 Hz, with a band-pass filter set at 0.1-200 Hz.19 The gating paradigm consisted of 700 250 Hz tone pairs presented at 50 dB HL via two speakers placed at +/-45° azimuth using E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools). The tones were created in Audacity, with a duration of 50 ms, including a 10 ms linear rise/fall time. The inter-stimulus interval was 500 ms and the intertrial interval was 7 seconds.10,11 CAEPs were time-locked to the onset of each tonal stimulus. Participants watched a muted movie with subtitles during EEG recordings to reduce effects of attention.11

Electroencephalography analysis

EEG recordings were high-pass filtered offline at 1 Hz, and segments created with -100 ms pre-stimulus and 350 ms post-stimulus times. EEG data were exported from Net Station into EEGLAB.20 Segments were baseline-corrected to the pre-stimulus period, and noisy channels were removed, followed by artifact rejection at +/- 100 μV. Removed channels were replaced with interpolated data via a spherical interpolation algorithm,19 and data were re-referenced using common average reference.

EEG data were down-sampled to 250 Hz, with a minimum of 300 segments in each individual grand CAEP tone 1 (S1) and tone 2 (S2) average. Due to hypotheses that gating in the frontal cortex may be atypical in tinnitus,9 as well as a previous study in which we found a frontal region of interest (ROI) to be sensitive to changes in frontal cortical activity,19 individual frontal ROIs were created from an average of thirteen electrodes (3, 4, 5, 9 or Fp2, 10, 11 or Fz, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 22 or Fp1, 23) (note that Electrical Geodesics electrode locations do not follow the 10-20 system). Amplitude (baseline to peak) and latency of CAEP peaks in response to S1 and S2 were measured at the frontal ROI and marked at the highest peak point or mid-peak for a broad peak. Approximate timeframes for peak components were as follows: Pa 25-45 ms, P50 50-90 ms, N1 90-130 ms, and P2 140-190 ms. Amplitude ratio and difference calculations (e.g., P50 amplitude S2/P50 amplitude S1, P50 amplitude S1-P50 amplitude S2) were performed for each participant at each peak component.

Statistical analyses

Multiple comparisons for statistical tests were corrected via the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate set at 0.1.21 Within-group comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA, and between-group comparisons were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric one-way ANOVA, due to the difference in sample size between groups. Correlational analyses were calculated using one-tailed Spearman’s rank order correlation. Exploratory statistical analyses for within-group TINN differences in high and low amplitude suppression were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Audiometry and speech perception

No significant difference was found between the EHF PTA for NTINN and TINN in either the right (U = 73, Z = 1.275, P > 0.05) or left ear (U = 73.5, Z = 1.311, P > 0.05). Similarly, SNR loss was found to be comparable between groups (U = 123.5, Z = -0.419, P > 0.05).

Auditory gating

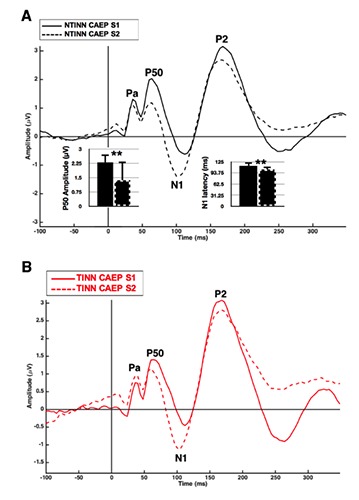

The NTINN group demonstrated CAEP P50 amplitude S2 suppression (F(1,34) = 8.25, ρ < 0.01), consistent with normal gating function10,11 (Figure 2A). No other peak components (i.e., Pa, N1, P2) showed evidence of amplitude suppression effects. There was a decrease in N1 latency for the second CAEP response (F(1,34) = 10.82, ρ < 0.01), which has also been reported in healthy gating.13 No other peak components showed a change in latency across the tonal pair.

Figure 2.

Auditory gating in normal hearing listeners with and without mild tinnitus. A) Cortical auditory evoked potential (CAEP) NTINN (n=18) responses to a 250 Hz tonal pair. Mean bar graphs illustrate significant P50 amplitude suppression and decrease in N1 latency in the CAEP S2 response. Error bars illustrate one standard deviation, and two asterisks indicate significance atρ < 0.01. B) CAEP TINN (n=15) responses to a 250 Hz tonal pair.

In contrast to the normal inhibitory processes observed in the NTINN group, Figure 2B shows a lack of gating in the TINN group. This finding is consistent with atypical inhibitory function described in clinical populations.12,13 Despite evidence of absent gating function in the TINN group, no significant differences were found between NTINN and TINN CAEP Pa, P50, N1 and P2 component amplitude gating indices. This may be due to variability of gating function in the TINN group, which is addressed in an exploratory analysis examining high and low amplitude suppressors in the TINN group.

Tinnitus severity correlations

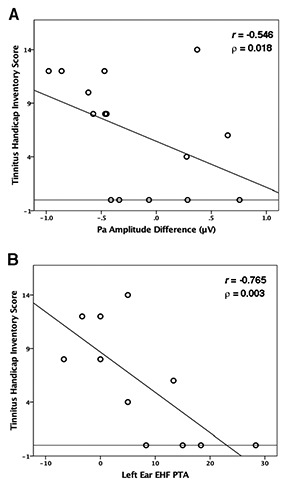

THI scores were correlated with CAEP amplitude gating indices to determine whether tinnitus severity varied with gating function. A moderate negative correlation was observed solely between the gating difference index of the Pa component and THI scores in the TINN group (r = -0.546, ρ = 0.018). In other words, as the CAEP responses between the two tones were similar, or there was increased amplitude in the second response, tinnitus severity also increased (Figure 3A). Similar findings have been reported for P50 amplitude difference values in schizophrenia with auditory hallucinations.13

Figure 3.

Tinnitus severity correlations. A) A significant correlation between cortical auditory evoked potential (CAEP) Pa amplitude gating difference values and Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) scores in the TINN group (n=15). B) A significant negative correlation between left ear extended high-frequency (EHF) pure tone average (PTA) and THI scores in the TINN group (n=11). The horizontal line indicates a THI severity rating of 0.

Because peripheral deafferentation in hearing loss has been linked to increased tinnitus severity,4 we investigated the relationship between EHF PTA values and THI scores. A strong negative correlation (r = -0.765, ρ = 0.003) between the THI and EHF PTA thresholds was present in the left ear (Figure 3B), showing that as thresholds were better in the extended frequency range, perception of tinnitus severity increased. This finding is inconsistent with tinnitus research showing a correlation between worse high frequency thresholds, illustrating a positive relationship between peripheral deafferentation and increased tinnitus severity.4

High suppressor and low suppressor gating in mild tinnitus

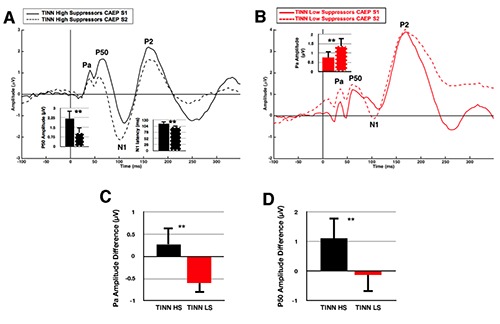

Due to the moderate correlation between Pa amplitude gating difference values and THI scores, an exploratory analysis was performed to determine if subcategories of high and low amplitude suppressors were present in the TINN group. High and low suppressors were separated according the TINN group median Pa amplitude difference. This method has been widely reported for separating high and low suppressors throughout the gating literature, though it is usually based on the P50 component median amplitude.15,22

Figure 4A shows the CAEP S1 and S2 waveforms for TINN high suppressors (n = 8). Normal gating function is present in this group, similar to that of the NTINN group (Figure 2A), with P50 amplitude significantly suppressed (U = 3, Z = -2.747, P < 0.01) and N1 latency significantly decreased in the CAEP S2 waveform (U = 3.5, Z = -2.729, P < 0.01). In contrast, the TINN low suppressors (n = 7) demonstrate a lack of gating (Figure 4B), as well as significantly increased Pa amplitude for the CAEP S2 waveform (U = 56, Z = 2.521, P = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Auditory gating in normal hearing listeners with tinnitus: High Versus Low Cortical Auditory Evoked Potential Amplitude Suppression. A) TINN (n=8) cortical auditory evoked potential (CAEP) responses to a 250 Hz tonal pair. The mean bar graphs illustrate significant P50 amplitude suppression and decrease in N1 latency in the CAEP S2 response. Error bars illustrate one standard deviation, and two asterisks indicate significance at ρ < 0.01. B) TINN (n=7) CAEP responses to a 250 Hz tonal pair. The mean bar graph illustrates a significant increase in Pa amplitude of the CAEP S2 waveform. C) Mean bar graph illustrating the significant difference between high amplitude suppressors (TINN HS, black) and low amplitude suppressors (TINN LS, red) for Pa amplitude difference. D) Mean bar graph illustrating the significant difference between TINN HS and LS for P50 amplitude difference.

CAEP amplitude difference indices were found to differ significantly between TINN high and low suppressors (U = 0, Z = -3.24, P = 0.001; U = 52, Z = 2.777, P < 0.01), with decreased Pa and P50 amplitude difference observed in the low suppressors (Figure 4C,D). These results are consistent with reduced amplitude suppression reported in the P35 and P50 components in clinical populations with atypical sensory processing.8,13

Discussion

In this study, we investigated central inhibitory function in normal hearing adults with and without mild tinnitus. High-density EEG was recorded in response to an auditory gating paradigm, and amplitude and latency of CAEP components, including peak amplitude gating indices, were compared. Tinnitus severity scores were correlated with amplitude gating indices. Finally, an exploratory analysis examined high and low amplitude suppressor subcategories in the TINN group.

We identified four findings: i) Adults with normal hearing and mild tinnitus demonstrated a lack of gating function, or inhibition; ii) Reduced inhibitory processes, reflected by the CAEP Pa amplitude difference index, were significantly correlated with tinnitus severity; iii) Lower EHF thresholds were significantly correlated with increased tinnitus severity; iv) Individuals with less severe tinnitus demonstrated gating function comparable to the control group, while those with more pronounced tinnitus exhibited aberrant gating performance.

Auditory gating in normal hearing adults with mild tinnitus

The NTINN adults showed expected amplitude suppression of the P50 component, as well as decreased N1 latency, in the second CAEP response (Figure 2A). In contrast, TINN adults showed no significant differences between CAEP S1 and S2 waveforms (Figure 2B), suggesting an absence of typical inhibitory processes.13 Intracranial and source localization research in healthy participants have shown the CAEP P50 gating response to arise from temporal sites with either simultaneous or later contri bution from frontal generators,6 with possible modulation from hippocampal sources.5 Thus, reduced gating function in the TINN group may reflect a deficit in cortical gating networks located in frontal cortex, or a combination of temporo-frontal networks operating in tandem.6

Disruption of cortical gating networks is likely due to variants in genotypes critical in inhibitory processes. COMT, a dopaminergic regulatory gene, and CHRNA7, a cholinergic regulatory gene, play a role in nicotine-modulated gating.15,23 Nicotinic receptor (nAChR) function is key to healthy gating, with deficits resulting in understimulation of inhibitory neurons.12 Because the results of the present study suggest reduced gating processes in normal hearing and tinnitus, it may be of interest to investigate genotypes in relation to gating function in this population.24

Tinnitus severity, auditory gating, and extended high frequency thresholds

The present study found that as the amplitude of the CAEP Pa S2 component becomes equal to or greater than the CAEP Pa S1 component, possibly from a lack of inhibition, tinnitus severity also increases (Figure 3A). Thus, the Pa amplitude difference index may act as a biomarker of tinnitus severity in this population. The Pa component, to our knowledge, has not been studied extensively as a mechanism of gating function, but has been reported to reflect amplitude suppression in healthy controls25 as well as a lack of suppression in patients with damage to prefrontal cortex.8 Research indicates that this component arises from generators in auditory cortex and deeper cortical structures,26 although the anatomical sources, especially involved in gating-related inhibitory processes, remain unclear. Our laboratory is currently conducting source analyses to determine whether decreased inhibition may be visualized through group differences in cortical network activation. 22

We also observed that tinnitus severity was increased in those with lower EHF PTA thresholds (Figure 3B). This result contradicts the tinnitus literature, which has consistently described increased tinnitus severity with higher audiometric thresholds,4 contributing to the hypothesis that peripheral deafferentation is likely to induce neuroplasticity responsible for the sustainment of the tinnitus percept2. It may be that decreased audiometric thresholds are related to an overall increase in auditory awareness, both to external and internal auditory signals.

High and low amplitude suppression in tinnitus

To better understand the variability of Pa amplitude suppression observed in the TINN participants, we performed preliminary exploratory analyses and stratified the group into high and low suppressors15 based on the group median of the Pa amplitude difference, which correlated significantly with tinnitus severity (Figure 3A). Studies in healthy controls have shown significant variability in gating function, and stratification of gating performance in this manner has been suggested as an important step in differentiating and understanding inhibitory processes in normal versus clinical populations.15

The disparity observed between high and low Pa amplitude suppression within the TINN group (Figure 4) indicates possible differences in cortical gating networks that may relate to the tinnitus percept. For instance, healthy subjects with low amplitude suppression tend to show reduced cortical network activity in frontal networks when compared to those with high amplitude suppression. 22 It is unclear which cortical networks may contribute to gating in the tinnitus population, though frontal and prefrontal networks have been suggested.9 Based upon previous gating research, the findings of the current study imply that frontal cortex is ineffective in the modulation of deeper temporal sources,22 but source localization analyses will be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Study limitations

While we identified deficits in auditory gating function in adults with normal hearing and mild tinnitus, limitations of the study should be addressed. First, cochlear synaptopathy may have been present in the TINN group, despite a lack of group differences in audiometric thresholds.27 Other measures have been shown to be more sensitive to this type of hearing loss. For instance, decreased otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) and OAE suppression, which involves cochlear mechanisms as well as crossed connections in the efferent medial olivocochlear system, have been described in adults with normal hearing thresholds and tinnitus.28 Similarly, decreased neural activity in cranial nerve VIII has been observed in individuals with noise exposure and clinically normal hearing,27 possibly affecting inhibitory function. However, it is of interest to note that there was no difference between the NTINN and TINN groups in speech perception in background noise performance. Deficits in this type of auditory task have been hypothesized to indicate cochlear synaptopathy in listeners with a normal audiogram.27,29 Another limitation of this study is that tinnitus severity was very mild, which may have led to there being no significant difference in CAEP amplitude gating indices between the NTINN and TINN groups. However, we believe this group still warrants investigation as to pathophysiology, especially as these individuals are possibly at a heightened risk for continued increase in tinnitus severity throughout the lifespan.30

Conclusions

This study presents novel evidence of aberrant gating function in normal hearing listeners with mild tinnitus. A lack of gating indicates reduced central inhibition, which may not necessarily be related to peripheral deafferentation, although cochlear synaptopathy in the individuals with mild tinnitus was not ruled out. We found that reduced CAEP Pa amplitude suppression significantly correlated with tinnitus severity, and that subgroups within the tinnitus group demonstrated high gating function comparable to the control group, while those with low gating function showed atypical gating responses. These results suggest that normal hearing individuals with normal EHF thresholds and speech perception performance may be at risk for increased tinnitus severity when there is a deficit in central inhibitory function.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Craig Champlin, PhD and Bharath Chandrasekaran, PhD for their insightful comments on the study design and manuscript.

Funding Statement

Funding: this work was supported by the Hearing Health Foundation Emerging Research Grant (2016) through the Les Paul Foundation and the Texas Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation Lear Ashmore Research Fund (2016).

References

- 1.Eggermont JJ, Roberts LE. The neuroscience of tinnitus. Trends Neurosci 2004;27:676-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norena AJ, Farley BJ. Tinnitus-related neural activity: Theories of generation, propagation, and centralization. Hear Res 2013;295:161-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Langguth B, Llinas R. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia: a theoretical update in tinnitus. Front Neuro 2015;6:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vielsmeier V, Lehner A, Strutz J, et al. The relevance of the high frequency audiometry in tinnitus patients with normal hearing in conventional pure-tone audiometry. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:302515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutros NN, Mears R, Pflieger ME, et al. Sensory gating in the human hippocampal and rhinal regions: regional differences. Hippocampus 2008;18:310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korzyukov O, Pflieger ME, Wagner M, et al. Generators of the intracranial P50 response in auditory sensory gating. Neuroimage 2007;35:814-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlcek P, Bob P, Raboch J. Sensory disturbances, inhibitory deficits, and the P50 wave in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:1309-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight RT, Staines WR, Swick D, Chao LL. Prefrontal cortex regulates inhibition and excitation in distributed neural networks. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1999;101:159-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauschecker JP, May ES, Maudoux A, Ploner M. Frontostriatal gating of tinnitus and chronic pain. Trends Cogn Sci 2015;19:567-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalecki A, Rodney JC, Johnstone SJ. An evaluation of P50 paired-click methodologies. Psychophysiol 2010;48:1692-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalecki A, Johnstone SJ, Croft RJ. Clarifying the functional process represented by P50 suppression. Int J Psychophysiol 2015;96:149-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Javitt DC, Freedman R. Sensory processing dysfunction in the personal experience and neuronal machinery of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:17-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DM, Grant B, Fisher DJ, et al. Auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia correlate with P50 gating. Clin Neurophysiol 2013;124:1329-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Salle S, Smith D, Choueiry J, et al. Effects of COMT genotype on sensory gating and its modulation by nicotine: Differences in low and high P50 suppressors. Neuroscience 2013;241:147-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knott V, de la Salle S, Smith D, et al. Baseline dependency of nicotine’s sensory gating actions: similarities and differences in low, medium and high P50 suppressors. J Psychopharmacol 2013;27:790-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivansic D, Guntinas-Lichius O, Muller B, et al. Impairments of speech comprehension in patients with tinnitus – A review. Front Aging Neurosci 2017;9:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granjeiro RC, Kehrle HM, de Oliveira TS, et al. Is the degree of discomfort caused by tinnitus in normal-hearing individuals correlated with psychiatric disorders? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;143:658-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell J, Sharma A. Compensatory changes in cortical resource allocation in adults with hearing loss. Front Syst Neurosci 2013;7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2004;134:9-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery ratea practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Statist Soc Series B: Methodological 1995;57:289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knott V, Millar A, Fisher D. Sensory gating and source analysis of the auditory P50 in low and high suppressors. Neuroimage 2009;44:992-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flomen RH, Shaikh M, Walshe M, et al. Association between the 2-bp deletion polymorphism in the duplicated version of the alpha7 nicotinic receptor gene and P50 sensory gating. Eur J Hum Genet 2013;21:76-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vona B, Nanda I, Shehata-Dieler W, Haaf T. Genetics of tinnitus: Still in its infancy. Front Neurosci 2017;11:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller MM, Keil A, Kissler J, Gruber T. Suppression of the auditory middle-latency response and evoked gamma-band response in a paired-click paradigm. Exp Brain Res 2001;136:474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson GP, Newman CW. The decomposition of the middle latency auditory evoked potential (MLAEP) Pa component into superficial and deep source contributions. Brain Topogr 1990;2:229-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberman MC, Epstein MJ, Cleveland SS, et al. Toward a differential diagnosis of hidden hearing loss in humans. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paglialonga A, Del Bo L, Ravazzani P, Tognola G. Quantitative analysis of cochlear active mechanisms in tinnitus subjects with normal hearing sensitivity: Multiparametric recording of evoked otoacoustic emissions and contralateral suppression. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010;37:291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pienkowski M. On the etiology of listening difficulties in noise despite clinically normal audiograms. Ear Hearing 2017;38:135-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez TG, Moraes F, Casseb J, et al. Tinnitus is associated with reduced sound level tolerance in adolescents with normal audiograms and otoacoustic emissions. Sci Rep 2016;6: 27109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]