Abstract

Background

Urine filtration and microhaematuria reagent strips are basic standard diagnostic methods to detect urogenital schistosomiasis. We assessed their accuracy for the diagnosis of light intensity infections with Schistosoma haematobium as they occur in individuals living in Zanzibar, an area targeted for interruption of transmission.

Methods

Urine samples were collected from children and adults in surveys conducted annually in Zanzibar from 2013 through 2016 and examined with the urine filtration method to count S. haematobium eggs and with the reagent strip test (Hemastix) to detect microhaematuria as a proxy for infection. Ten percent of the urine filtration slides were read twice. Sensitivity was calculated for reagent strips, stratified by egg counts reflecting light intensity sub-groups, and kappa statistics for the agreement of urine filtration readings.

Results

Among the 39,207 and 18,155 urine samples examined from children and adults, respectively, 5.4% and 2.7% were S. haematobium egg-positive. A third (34.7%) and almost half (46.7%) of the egg-positive samples from children and adults, respectively, had ultra-low counts defined as 1–5 eggs per 10 ml urine. Sensitivity of the reagent strips increased significantly for each unit log10 egg count per 10 ml urine in children (odds ratio, OR: 4.7; 95% confidence interval, CI: 4.0–5.7; P < 0.0001) and adults (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.9–3.7, P < 0.0001). Sensitivity for diagnosing ultra-light intensity infections was very low in children (50.1%; 95% CI: 46.5–53.8%) and adults (58.7%; 95% CI: 51.9–65.2%). Among the 4477 and 1566 urine filtration slides read twice from children and adults, most were correctly identified as negative or positive (kappa = 0.84 for children and kappa = 0.81 for adults). However, 294 and 75 slides had discrepant results and were positive in only one of the two readings. The majority of these discrepant slides (76.9% of children and 84.0% of adults) had counts of 1–5 eggs per 10 ml urine.

Conclusions

We found that many individuals infected with S. haematobium in Zanzibar excrete > 5 eggs per 10 ml urine. These ultra-light infections impose a major challenge for accurate diagnosis. Next-generation diagnostic tools to be used in settings where interruption of transmission is the goal should reliably detect infections with ≤ 5 eggs per 10 ml urine.

Trial Registration

ISRCTN, ISRCTN48837681. Registered 05 September 2012 - Retrospectively registered.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-018-3136-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Control, Diagnosis, Elimination, Macrohaematuria, Microhaematuria, Reagent strip, Schistosoma haematobium, Surveillance, Urine filtration, Urogenital schistosomiasis, Zanzibar

Background

Urogenital schistosomiasis, caused by the blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium, is a common neglected tropical disease (NTD) in many countries of sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East [1, 2]. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) encouraged endemic countries to increase the coverage of preventive chemotherapy programmes for the control of morbidity due to schistosomiasis and to initiate elimination campaigns where appropriate, through strengthened health systems, intensified treatment, provision of water and sanitation, addition of health education for behaviour change and snail control to the programmes [3, 4]. As a reaction, over the past years, efforts for control and elimination of schistosomiasis have substantially increased.

The typical sign for urogenital schistosomiasis is the presence of blood in urine [5]. High-risk communities can be identified by using a simple questionnaire asking for visible blood (macrohaematuria) in urine [6, 7]. Another recommended proxy for a S. haematobium infection is the detection of microhaematuria using reagent strips [8–10]. The standard method for urogenital schistosomiasis diagnosis in endemic areas is the microscopic quantification of S. haematobium eggs in urine using polycarbonate filters [7, 11]. However, after praziquantel treatment and repeated preventive chemotherapy, macro- and microhaematuria decrease, as well as intensities of infection and the overall prevalence [12–15]. Hence, in areas that have achieved morbidity control (prevalence of heavy-intensity infection < 5% across sentinel sites) and move towards elimination of urogenital schistosomiasis as public health problem (prevalence of heavy-intensity infections < 1% in all sentinel sites) and finally interruption of transmission (reduction of incidence of infection to zero) according to WHO thresholds [4], macro- and microhaematuria and the number of eggs excreted in urine will be extremely low and eventually zero. These light intensity infections impose a challenge for accurate diagnosis.

A large dataset with S. haematobium diagnostic results was derived from a 5-year cluster randomized trial assessing different interventions against urogenital schistosomiasis in Zanzibar funded by the Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE) [16]. Zanzibar is one of the first areas in sub-Saharan Africa that is targeted for urogenital schistosomiasis elimination as public health problem and interruption of transmission. Using these data, we aimed to assess whether the sensitivity of microhaematuria testing using reagent strips increases with increasing egg counts measured with the standard urine filtration method. In addition, we aimed to determine the diagnostic test sensitivity at different light intensity infection sub-groups.

Methods

Study area

The Zanzibar islands, Unguja and Pemba, are part of the United Republic of Tanzania. The population size is estimated at 1.3 million. Historically, urogenital schistosomiasis has been a considerable public health problem on both islands [17–19]. Over the past decades, regular mass drug administration (MDA) with praziquantel, improved access to safe water, better socio-economic conditions and likely also climatic changes have lowered the disease prevalence and reduced morbidity [20, 21]. Efforts to eliminate urogenital schistosomiasis as public health problem on Pemba and to interrupt transmission on Unguja started in 2011 by the Zanzibar Elimination of Schistosomiasis Transmission (ZEST) alliance [16, 22]. These efforts were fostered by a three-arm multi-year cluster randomized trial implemented from 2011 to 2017 to assess the effect of biannual MDA, snail control and behaviour change interventions [16]. To date, with the exception of some areas where transmission is still considerably high [21], the prevalence of S. haematobium infections is well below 10% and infection intensities are light in most administrative areas (shehias).

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculations for the cluster randomized trial and annual cross-sectional surveys in schools and communities are provided elsewhere [16]. The results of all individuals with a complete urine examination, by urine filtration and reagent strip methods, in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016, were included into the analyses presented here.

Field procedures

The cross-sectional surveys in schools and communities were conducted annually, in both Unguja and Pemba, between February and June in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016. Children aged 9–12 years attending the study primary schools and adults aged 20–55 years living in the study communities were included. In each primary school, the headmaster and teachers were informed about the aims of the study and in each community the community leader was consulted. The participant selection procedure in schools and communities has been described elsewhere in detail [16]. In brief, in public primary schools, classes of grades 3 and 4 were visited by the field teams of the NTD Programme and the Public Health Laboratory-Ivo de Carneri (PHL-IdC) on Unguja and Pemba, respectively. The purpose of the study was explained in lay terms to the children. The name, age, sex, and additional demographic information of the selected children were recorded. The children registered for participation received an information sheet and a consent form to bring to their parents. The following day, each child returning the consent form signed by its parent or legal guardian received a urine collection container and was asked to fill the container with its own urine (urine collection occurred between 10:00 and 12:00 hours) and to give the filled container to the field team. In each shehia, households were randomly selected and an adult household member, present at the time, was invited to participate in the study [16]. After consenting and replying to a brief questionnaire concerning demographic characteristics, the adult received a container for collection of his/her own urine. All urine samples from adults were collected between 10:00 and 14:00 hours. The urine samples collected in Unguja were examined in the laboratory of the NTD Programme of the Ministry of Health in Zanzibar Town, Unguja. The urine samples collected in Pemba were examined in the PHL-IdC in Chake Chake, Pemba.

Laboratory procedures

On the day of collection, all urine samples (i.e. one single sample per person) were examined by trained laboratory technicians for macrohaematuria using a colour chart and for microhaematuria using reagent strips (Hemastix; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics GmbH, Eschborn, Germany). Macrohaematuria was graded with numbers from 1 to 6 from transparent to dark red urine using a pretested colour chart [23, 24]. Microhaematuria in urine was coded semi-quantitatively according to the Hemastix manufacturer’s instructions (negative; trace; +; ++; and +++). Additionally, all urine samples of sufficient quantity were rigorously shaken and 10 ml of each sample pressed through a polycarbonate filter with a pore size of 20 μm (Sterlitech, Kent, WA, USA) using a standard 10 ml plastic syringe. All urine filters were put on a microscope slide, covered with a piece of hydrophilic cellophane soaked in glycerol solution, and examined by trained laboratory technicians under the microscope using some drops of Lugol’s iodine to stain S. haematobium eggs after cellophane coverage. The presence and number of S. haematobium eggs was recorded. After microscopy, the slides were stored at room temperature for a potential second reading for quality control. Quality control was performed on 10% of the stored urine filtration slides several months after the initial reading. For the selection of quality control urine filtration (QCUF) slides, 10% of the slides of each technician were included, prioritizing slides from microhaematuria-positive urine samples and adding computer randomized microhaematuria-negative slides until the number representing 10% of the total number of slides read by the technician was reached. The QCUF slides were read by trained external microscopists who were blinded to the reagent strip and initial urine filtration results.

Data management and analysis

The macrohaematuria, microhaematuria, urine filtration, and QCUF results were recorded on paper laboratory forms and subsequently entered into a Microsoft Excel 2010 electronic database (Microsoft Corporation 2010) and cleaned. Data were analysed using STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). Only data from urine samples with complete examination (i.e. microhaematuria, microhaematuria and urine filtration result available) and from children aged 9-12 years or adults aged 20-55 years were included in the analyses.

Microhaematuria-positive was defined as a urine sample that had a trace or positive reagent strip colour reaction. S. haematobium-positive was defined as a urine filtration slide that contained at least one S. haematobium egg. The WHO differentiates S. haematobium infections into light (1–49 eggs per 10 ml urine) and heavy (≥ 50 eggs per 10 ml urine) intensity [25]. In our study we further stratified egg counts into the following sub-classes: “negative” (0 eggs/10 ml), “ultra-light” (1–5 eggs/10 ml), “very light” (6–10 eggs/10 ml), “light” (11–49 eggs/10 ml) and “heavy” (≥ 50 eggs/10 ml) infections. Association between S. haematobium infection (binary outcome variable or categorical explanatory variable) and microhaematuria (binary outcome variable or categorical explanatory variable) was assessed by multivariable logistic regression analyses, adjusted by sex (binary variable), age (continuous variable), study year (categorical variable) and school or shehia as a sampling unit (categorical variable) and expressed as odds ratios (OR) plus 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

For both children and adults separately, the sensitivity and specificity of the reagent strip method was calculated overall and stratified by the egg count thresholds chosen for ultra-light, very light, light, and heavy infections as described above. The original urine filtration was considered as the diagnostic reference test. The sensitivity of a reagent strip result was calculated as the proportion of positives that were correctly identified when compared to the reference test. The specificity of a reagent strip result was calculated as the proportion of negatives that were correctly identified when compared to the reference test. We used 95% CIs to indicate the contrast between groups. In addition, we used logistic regression to assess whether the sensitivity of the reagent strip method is increasing with increasing egg counts determined by the urine filtration method. For this purpose we used the decimal logarithm of the egg counts of the filtration-positive samples as predictor. The graphical representation of the predicted values is shown in Additional file 1.

The agreement between the positive and negative readings of the original urine filtration versus the QCUF reading was determined using kappa (κ)-statistics. The κ-statistics were interpreted as follows: < 0.00 indicating no agreement; 0.00–0.20 indicating slight agreement; 0.21–0.40 indicating fair agreement; 0.41–0.60 indicating moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80 indicating substantial agreement; 0.81–0.99 indicating almost perfect agreement; and 1.00 indicating perfect agreement [26].

Results

Study participation and operational results

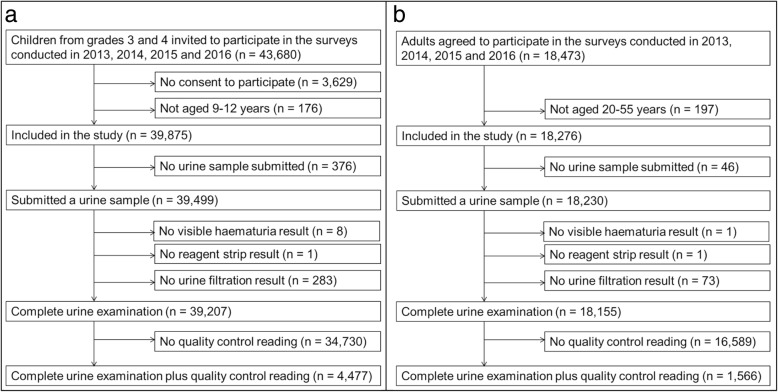

As shown in Fig. 1a, a total of 43,680 children were invited to participate in the cross-sectional surveys conducted in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016. Among them, 39,875 were aged 9–12 years and submitted a signed form from their parents consenting to their participation. Complete urine sample examinations including results on macrohaematuria, microhaematuria and S. haematobium egg counts were available for 39,207 children. Among them, 20,680 (52.7%) were girls and 18,527 (47.3%) were boys. A QCUF reading was performed for 4477 slides.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart detailing study participation and urine sampling procedures. a Children sampled in public primary schools. b Adults sampled in communities in Unguja and Pemba islands, United Republic of Tanzania

Figure 1b indicates that a total of 18,473 adults participated in the study. Among them, 18,276 were aged 20–55 years and included in the study. Complete urine sample examinations were available for 18,155 adults. Among them, 10,573 (58.2%) were female and 7582 (41.8%) were male. A QCUF reading was performed for 1566 slides.

Association between infection intensity and haematuria in children

As shown in Table 1, among the 39,207 urine filtration slides examined for S. haematobium infection in children, 2130 (5.4%) were found to be egg-positive. Among the S. haematobium-positive slides, ultra-light infections with 1–5 eggs/10 ml urine were most common (34.7%). Very light infections with 6–10 eggs/10 ml were found in 13.3%, light infections with 11–49 eggs/10 ml were found in 30.3%, and heavy infections with ≥ 50 eggs/10 ml urine were found in 21.6% of the S. haematobium-positive slides. Among all urine samples examined, 1.2% were identified with heavy infection intensities.

Table 1.

Multivariate frequency distribution of S. haematobium infection and egg counts and haematuria presence and grading

| Urine filtration original reading | Microhaematuria | Microhaematuria grading | Macrohaematuria grading | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n negative | n positive including trace | % positive | Trace | + | ++ | +++ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Total children examined | 39,207 | 36,675 | 2532 | 6.5 | |||||||||||

| S. haematobium egg-negative | 37,077 | 94.6 | 36,070 | 1007 | 2.7 | 430 | 264 | 205 | 108 | 19,070 | 14,265 | 3508 | 223 | 11 | 0 |

| S. haematobium egg-positive | 2130 | 5.4 | 605 | 1525 | 71.6 | 292 | 290 | 468 | 475 | 801 | 1030 | 279 | 18 | 2 | 0 |

| S. haematobium egg counts | |||||||||||||||

| 1–5 eggs | 740 | 34.7 | 369 | 371 | 50.1 | 102 | 91 | 116 | 62 | 332 | 216 | 89 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| 6–10 eggs | 284 | 13.3 | 85 | 199 | 70.1 | 52 | 41 | 62 | 44 | 117 | 137 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 11–49 eggs | 646 | 30.3 | 119 | 527 | 81.6 | 103 | 113 | 167 | 144 | 234 | 325 | 81 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 50+ eggs | 460 | 21.6 | 32 | 428 | 93.0 | 35 | 45 | 123 | 225 | 118 | 252 | 81 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Total adults examined | 18,155 | 16,131 | 2024 | 11.1 | |||||||||||

| S. haematobium egg-negative | 17,673 | 97.3 | 15,985 | 1688 | 9.6 | 541 | 475 | 383 | 289 | 7275 | 7972 | 2250 | 170 | 5 | 1 |

| S. haematobium egg-positive | 482 | 2.7 | 146 | 336 | 69.7 | 65 | 62 | 99 | 110 | 157 | 245 | 67 | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| S. haematobium egg counts | |||||||||||||||

| 1–5 eggs | 225 | 46.7 | 93 | 132 | 58.7 | 28 | 40 | 29 | 35 | 80 | 109 | 31 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 6–10 eggs | 64 | 13.3 | 18 | 46 | 71.9 | 11 | 5 | 19 | 11 | 25 | 27 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 11–49 eggs | 124 | 25.7 | 27 | 97 | 78.2 | 17 | 14 | 32 | 34 | 38 | 71 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 50+ eggs | 69 | 14.3 | 8 | 61 | 88.4 | 9 | 3 | 19 | 30 | 14 | 38 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Table 1 indicates that the majority of urines were lightly coloured and only very few children and adults had visible haematuria. A total of 2532 (6.5%) urine samples from children were microhaematuria-positive. Among the 2130 S. haematobium egg-positive urine samples, 605 (71.6%) were microhaematuria-positive and among the 37,077 S. haematobium egg-negative urine samples, 1007 (2.7%) were microhaematuria-positive.

Compared with S. haematobium egg-negative children, egg-positive children had significantly higher odds to present with microhaematuria (OR: 85.7; 95% CI: 74.9–98.1). The odds increased with increasing egg counts and were highest for heavy (OR: 604.2; 95% CI: 414.5–880.8), followed by light (OR: 208.7; 95% CI: 166.0–265.5), very light (OR: 96.1; 95% CI: 72.8–126.9), and ultra-light (OR: 45.0; 95% CI: 37.6–53.9) infections. Boys had higher odds to be S. haematobium-positive (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.7–2.2) but lower odds to be microhaematuria-positive (OR: 0.9; 95% CI: 0.7–0.9) than girls. More details about the associations between S. haematobium infection intensity and microhaematuria are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2a.

Table 2.

Association between S. haematobium egg counts and microhaematuria

| Variable type | Variable name | n | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children aged 9–12 years | 39,207 | |||

| Outcome | S. haematobium egg-positive | |||

| Explanatory | Microhaematuria-positive | 86.6 | 75.6–99.1 | |

| Trace | 42.8 | 35.0–52.3 | ||

| + | 66.8 | 53.4–83.2 | ||

| ++ | 129.6 | 104.2–161.2 | ||

| +++ | 188.8 | 146.5–243.3 | ||

| Boys | 1.9 | 1.67–2.17 | ||

| Outcome | Microhaematuria-positive | |||

| Explanatory | S. haematobium egg-positive | 85.7 | 74.9–98.1 | |

| 1-5 eggs | 45 | 37.6–53.9 | ||

| 6-10 eggs | 96.1 | 72.8–126.9 | ||

| 11-49 eggs | 208.7 | 166.0–262.5 | ||

| 50+ eggs | 604.2 | 414.5–880.8 | ||

| Boys | 0.83 | 0.74–0.93 | ||

| Adults aged 20–55 years | 18,155 | |||

| Outcome | S. haematobium egg-positive | |||

| Explanatory | Microhaematuria-positive | 29.6 | 23.6–37.2 | |

| Trace | 19.3 | 13.7–27.1 | ||

| + | 21.6 | 15.3–27.1 | ||

| ++ | 34.6 | 25.3–47.3 | ||

| +++ | 50.2 | 36.4–69.3 | ||

| Men | 2.5 | 2.0–3.1 | ||

| Outcome | Microhaematuria-positive | |||

| Explanatory | S. haematobium egg-positive | 29.5 | 23.6–36.8 | |

| 1–5 eggs | 19.9 | 15.0–26.3 | ||

| 6–10 eggs | 42.3 | 24.2–74.0 | ||

| 11–49 eggs | 50.6 | 32.0–79.9 | ||

| 50+ eggs | 129.1 | 60.6–274.8 | ||

| Men | 0.5 | 0.44–0.55 | ||

Abbreviations: OR odds ratio; 95% CI 95% confidence interval

Fig. 2.

Boxplots of S. haematobium log egg counts of egg-positive urine samples from Zanzibar, United Republic of Tanzania, stratified by microhaematuria grading, sex and age category. a log S. haematobium egg-counts by microhaematuria grading for female and male children. b log S. haematobium egg-counts by microhaematuria grading for female and male adults. Correlation between positive egg counts and microhaematuria grading (data pooled over both sexes): Spearman’s rho in children= 0.65, P < 0.001 (n = 39,207), Spearman’s rho in adults = 0.32; P < 0.001 (n = 18,155). In contrast to the boxplots, the correlation coefficients were calculated using egg counts from positive and negative urine samples

Association between infection intensity and haematuria in adults

As shown in Table 1, among the 18,155 urine filtration slides examined for S. haematobium infection in adults, 482 (2.7%) were egg positive. Ultra-light infections were most common (46.7%), followed by light (25.7%), heavy (14.3%) and very light (13.3%) infections. Among all examined urine samples, 0.4% were identified with heavy infection intensities. Among the S. haematobium egg-positive samples, 336 (69.7%) were microhaematuria-positive and among the egg-negative urine samples, 1688 (9.6%) were microhaematuria-positive.

Adults had higher odds to be microhaematuria-positive if S. haematobium eggs were found in their urine (OR: 29.5; 95% CI: 23.6–36.8). The odds increased with increasing egg counts (Table 2). They were highest for heavy (OR: 129.1; 95% CI: 60.6–274.8), followed by light (OR: 50.6; 95% CI: 32.0–79.9), very light (OR: 42.3; 95% CI: 24.2–74.0), and ultra-light (OR: 19.9; 95% CI: 15.0–26.3) infections. Men had higher odds to be S. haematobium-positive (OR: 2.5; 95% CI: 2.0–3.1) but lower odds to be microhaematuria-positive (OR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.4–0.6) than women.

Specificity and sensitivity of the reagent strip method

As shown in Table 3, in children, the specificity of the reagent strip method was 97.3% (97.1–97.4%). The overall sensitivity was 71.6% (95% CI: 69.6–73.5%). When considering intensity subgroups, the sensitivity was lowest for ultra-light infections (50.1%; 95% CI: 46.5–53.8%), followed by very light (70.1%; 95% CI: 64.4–75.3%), light (81.6%; 95% CI: 78.4–84.5%), and heavy (93.0%; 95% CI: 90.3–95.2%) infections.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of the reagent strip method for S. haematobium diagnosis in children when urine filtration results are considered as reference test

| Reference test: urine filtration | Microhaematuria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals included | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 1525 | 605 | 2130 | |

| Negative | 1007 | 36,070 | 37,077 | |

| Total | 2532 | 36,675 | 39,207 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 71.6% (69.6–73.5%) | |||

| Specificity of reagent strips | 97.3% (97.1–97.4%) | |||

| Subgroup: 1–5 eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 371 | 369 | 740 | |

| Negative | 1007 | 36,070 | 37,077 | |

| Total | 1378 | 36,439 | 37,817 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 50.1% (46.5–53.8%) | |||

| Subgroup: 6–10 eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 199 | 85 | 284 | |

| Negative | 1007 | 36,070 | 37,077 | |

| Total | 1206 | 36,155 | 37,361 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 70.1% (64.4–75.3%) | |||

| Subgroup: 11–49 eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 527 | 119 | 646 | |

| Negative | 1007 | 36,070 | 37,077 | |

| Total | 1534 | 36,189 | 37,723 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 81.6% (78.4–84.5%) | |||

| Subgroup: 50+ eggs/10 m | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 428 | 32 | 460 | |

| Negative | 1007 | 36,070 | 37,077 | |

| Total | 1435 | 36,102 | 37,537 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 93.0% (90.3–95.2%) | |||

As indicated in Table 4 among adults, the specificity of the reagent strip method was 90.4% (95% CI: 90.0–90.9%). The overall sensitivity was 69.7% (95% CI: 65.4–73.8%). Stratified by intensity, the sensitivity was 58.7% (95% CI: 51.9–65.2%) for ultra-light, 71.9% (95% CI: 59.2–82.4%) for very light, 77.9% (95% CI: 69.5–84.9%) for light and 88.7% (95% CI: 79.0–95.0%) for heavy infections.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of the reagent strip method for S. haematobium diagnosis in adults when urine filtration results are considered as reference test

| Reference test: urine filtration | Microhaematuria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals included | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 336 | 146 | 482 | |

| Negative | 1688 | 15,985 | 17,673 | |

| Total | 2024 | 16,131 | 18,155 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 69.7% (65.4–73.8%) | |||

| Specificity of reagent strips | 90.4% (90.0–90.9%) | |||

| Subgroup: 1–5 eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 132 | 93 | 225 | |

| Negative | 1688 | 15,985 | 17,673 | |

| Total | 1820 | 16,078 | 17,898 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 58.7% (51.9–65.2%) | |||

| Subgroup: 6–10 eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 46 | 18 | 64 | |

| Negative | 1688 | 15,985 | 17,673 | |

| Total | 1734 | 16,003 | 17,737 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 71.9% (59.2–82.4%) | |||

| Subgroup: 11–49 eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 95 | 27 | 122 | |

| Negative | 1688 | 15,985 | 17,673 | |

| Total | 1783 | 16,012 | 17,795 | |

| Sensitivity of reagent strips | 77.9% (69.5–84.9%) | |||

| Subgroup: 50+ eggs/10 ml | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 63 | 8 | 71 | |

| Negative | 1688 | 15,985 | 17,673 | |

| Total | 1751 | 15,993 | 17,744 | |

| Sensitivity | 88.7% (79.0–95.0%) | |||

Additional file 1 shows that the sensitivity of the reagent strip method increased significantly for each unit log10 egg count per 10 ml urine in children (OR: 4.7; 95% CI: 4.0–5.7, P < 0.0001) and adults (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.9–3.7, P < 0.0001). The difference of the test sensitivity between children and adults (P = 0.001) as well as the population-egg-count interaction (P = 0.002) were statistically significant.

Urine filter microscopy

Table 5 shows that among the 4477 urine filtration slides from children that were subjected to QCUF, 3087 slides were negative and 1096 slides were recorded as egg-positive in both the original and the QCUF reading. The kappa-agreement was almost perfect (κ = 0.84). However, 163 slides were only positive in the original and 131 slides were only positive in the QCUF reading. As presented in Table 5, among the 294 slides that were only positive in one or the other microscopy reading, 93 slides had an egg count of 1 (31.6%). The vast majority of the discrepant slides had egg counts between 1 and 5 (76.9%), followed by egg counts between 6 and 10 (12.2%), egg counts between 11 and 49 (7.5%), and 50 and above (3.4%).

Table 5.

Schistosoma haematobium egg counts on discrepant slides when examined by original or quality control urine filtration (QCUF) microscopy

| Microscopic examination | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Slides with original and QCUF reading | 4477 | |

| Slides with positive results in both readings | 1096 | ||

| Slides with negative results in both readings | 3087 | ||

| Slides with discrepant results (one reading positive, one reading negative) | 294 | ||

| S. haematobium egg counts on discrepant slides | |||

| 1 egg | 93 | 31.6 | |

| 2 eggs | 57 | 19.4 | |

| 3 eggs | 39 | 13.3 | |

| 4 eggs | 23 | 7.8 | |

| 5 eggs | 14 | 4.8 | |

| 1–5 eggs | 226 | 76.9 | |

| 6–10 eggs | 36 | 12.2 | |

| 11–49 eggs | 22 | 7.5 | |

| 50+ eggs | 10 | 3.4 | |

| Adults | Slides with original and QCUF reading | 1566 | |

| Slides with positive results in both readings | 199 | ||

| Slides with negative results in both readings | 1292 | ||

| Slides with discrepant results (one reading positive, one reading negative) | 75 | ||

| S. haematobium egg counts on discrepant slides | |||

| 1 egg | 34 | 45.3 | |

| 2 eggs | 12 | 16.0 | |

| 3 eggs | 6 | 8.0 | |

| 4 eggs | 7 | 9.3 | |

| 5 eggs | 4 | 5.3 | |

| 1–5 eggs | 63 | 84.0 | |

| 6–10 eggs | 10 | 13.3 | |

| 11–50 eggs | 1 | 1.3 | |

| 51+ eggs | 1 | 1.3 | |

A total of 1566 urine filtration slides from adults were subjected to QCUF. Among them, 1292 were negative and 199 were recorded as egg-positive in both the original and the QCUF reading. Hence, the kappa-agreement was almost perfect (κ = 0.81). However, 35 slides were only positive in the original reading and 40 slides were only positive in the QCUF reading. For adults, among the 75 slides that had discrepant results, almost half (45.3%) had an egg count of 1. The majority of the discrepant slides, had egg counts between 1 and 5 (84.0%), followed by egg counts between 6 and 10 (13.3%), egg counts between 11 and 49 (1.3%), and 50 and above (1.3%).

Discussion

Reagent strips and urine filtration are basic standard diagnostic methods to detect urogenital schistosomiasis [7, 27–29]. Their sensitivity is, however, reduced in low prevalence settings, treated populations, or subgroups with light intensity infections [27, 30, 31]. Moving towards the goal of interruption of Schistosoma transmission, it is important to assess at what level of egg counts the diagnostic methods start to lose their accuracy. Here, we evaluated the performance of urine filtration readings and microhaematuria assessment for diagnosing S. haematobium infections in several thousand urine samples from children and adults living in Zanzibar, an area targeted for interruption of transmission of urogenital schistosomiasis.

Our study clearly showed that both reagent strip and urine filtration method have a particularly low diagnostic accuracy for the detection of ultra-light infections with egg counts of 1–5 eggs per 10 ml of urine. In line with a recent meta-analysis, indicating sensitivities of reagent strips of 65% for light intensity infection and 72% for post-treatment groups [30], the overall sensitivity to detect S. haematobium infections with reagent strips in children and adults in our study was 71.6% and 69.7%, respectively. However, the sensitivity of reagent strips to detect ultra-light infections was considerably lower (50.1% in children and 58.7% in adults). Comparing the results of urine filtration microscopy, we found that the overall agreement when slides were read twice was almost perfect. However, false-negative diagnosis by one of the two readings occurred and particularly when egg counts were between 1 and 5 eggs per 10 ml urine.

In Zanzibar, only a small portion of the samples examined by urine filtration were S. haematobium egg-positive (5.4% of children and 2.7% of adults) and more than a third of these egg-positive slides showed ultra-light infections with 1–5 eggs per 10 ml urine (34.7% of children and 46.7% of adults). Only about half of these ultra-lightly infected individuals (50.1% of children and 58.7% of adults) presented with detectable microhaematuria. Our results highlight that a large proportion of individuals living in elimination settings such as Zanzibar that are targeted by regular interventions harbour ultra-light infections. These cases may be missed when reagent strips or single urine filtration readings are applied as diagnostic approach. Hence, in settings where interruption of transmission is the goal and already the excretion of a single egg into a water body with intermediate host snails can result in resurgence of transmission and (re-)infection of a whole community, more sensitive diagnostic methods are needed to identify and subsequently treat infected individuals. These next-generation diagnostic tools should be able to reliably detect infections with ≤ 5 eggs per 10 ml urine.

In line with other studies, the performance of both reagent strips and urine filtration improved significantly when egg counts increased [12, 18, 27]. The odds of urine samples being microhaematuria-positive increased significantly from ultra-light to very light to light to heavy infection egg outputs. Also, the number of false-negative or false-positive urine filtration slide readings decreased considerably with increasing egg counts. Only very few slides were wrong-negative or wrong-positive at counts of ≥ 50 eggs per 10 ml urine, errors that might be attributed to wrong labelling.

Hence, urine filtration and reagent strip methods are valid means to detect S. haematobium infections in epidemiological surveys and outpatient centres in areas where infection intensities are reasonably high [30, 32]. In areas identified to have high prevalences and infection intensities, preventive chemotherapy without individual diagnosis will be the key intervention to control morbidity [7]. Urine filtration and reagent strips might also be suitable tools for monitoring progress in areas where preventive chemotherapy plus complementary interventions are used to achieve elimination as a public health problem. However, only urine filtration allows classification of S. haematobium infections into light and heavy intensities as defined by the WHO [25]. Where interruption of transmission is the goal, novel intervention strategies need to be considered and tested. The sensitive and specific identification of infected individuals excreting S. haematobium eggs, including ultra-lightly infected individuals, will gain importance. Hence, next-generation diagnostic tools that are reliably working below a level of 5 eggs per 10 ml urine are urgently needed.

A first step into improved diagnosis of S. haematobium infections in population groups excreting low numbers of eggs was done with the development and evaluation of the up-converting phosphor-lateral flow circulating anodic antigen (UCP-CAA) assay and the detection of parasite specific DNA Dra1 fragments in urine using PCR-based methods, respectively [29, 31, 33–35]. However, these tests need a considerable amount of equipment, material and training of technicians and will hence mostly be of use in well-equipped central laboratories. For monitoring and surveillance at the peripheral level, e.g. in local schools and health facilities, a simple rapid diagnostic test with high sensitivity such as the point-of-care circulating cathodic antigen test available for S. mansoni [36, 37] is needed also for S. haematobium diagnosis. Such a sensitive rapid diagnostic test would facilitate focal screen-and-treat and other tailored surveillance-response scenarios that could become part of a strategy for interrupting S. haematobium transmission.

A clear limitation of our study is that no third and highly sensitive diagnostic method such as the UCP-CAA or PCR was used to validate results derived with the urine filtration and reagent strip methods. Also the collection of multiple urine samples from the same individuals would have allowed to assess more thoroughly the relationship between low egg intensity and macro- or microhaematuria while accounting for variation between individuals as well as changes in egg excretion during the day. Nevertheless, the analysis of our large dataset allows for the following conclusions and considerations.

Conclusions

We found that ultra-light S. haematobium infections are most common in Zanzibar and impose a major challenge for accurate diagnosis using basic parasitological methods. Next-generation diagnostic tools to be used in settings where interruption of transmission is the goal should reliably detect infections ≤ 5 eggs per 10 ml urine. These new tests should not only be highly sensitive, but also rapid and easy to apply so that they can be used for surveillance at the central and peripheral level, triggering an effective and focused intervention response.

Additional file

Predicted sensitivity of reagent strips by infection intensity estimated by urine filtration. The sensitivity of the reagent strip method to detect microhaematuria increased significantly for each unit log10 egg count per 10 ml urine in children (odds ratio, OR: 4.7; 95% confidence interval, CI: 4.0–5.7, P < 0.0001) and adults (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.9–3.7, P < 0.0001). The difference of the test sensitivity between children and adults (P = 0.001) as well as the population-egg-count interaction (P = 0.002) were statistically significant. (PDF 32 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE) secretariat for advisory support. We thank the staff of the parasitology teams in Unguja and Pemba who helped with the collection and examination of urine samples, subjected to haematuria testing and urine filtration. We acknowledge Colin Cercamondi for helping with the quality control of urine filtration slides in 2013. Last but not least, we acknowledge the children and adults participating in our study.

Funding

This study received financial support from the University of Georgia Research Foundation Inc., which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for these Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE) projects (prime award no. 50816, sub-award no. RR374-053/4893206). SK is financially supported by sub-award no. RR374-053/4893196. SK is also financially supported by a direct grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Investment ID: OPP1191423). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the study: SK and DR. Acquisition of data: SK, SMAm, SMAl, FB, MAK, ISK and FK. Analysis and interpretation of data: SK, JH and DR. Drafting the article: SK. Revising the article critically for important intellectual content: SMAm, JH, SMAl, FB, MAK, ISK, BP, FK and DR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study protocol was approved by the Zanzibar Medical Research Ethics Committee (ZAMREC) in Zanzibar, United Republic of Tanzania (reference no. ZAMREC 0003/Sept/011), the Ethics Committee of Basel, Switzerland (reference no. EKBB 236/11), and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Georgia in the USA (project no. 2012-10138-0) [16]. The study is registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number register (ISRCTN48837681). All children and adults invited to participate in the study received a participant information sheet and a consent sheet. The study was explained in lay terms to the children in school and to the adults in the communities using the local language Kiswahili. Only individuals, who submitted a written informed consent for their participation, were included in the study. In the case of children, parents or their legal guardians were asked to provide their written consent for the child’s participation. All study participants were offered praziquantel (40 mg/kg) against schistosomiasis and albendazole (400 mg) against soil-transmitted helminthiasis free of charge via the biannual island-wide mass drug administration conducted as part of the elimination interventions by the Zanzibar Neglected Diseases Programme in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Stefanie Knopp, Email: s.knopp@swisstph.ch.

Shaali M Ame, Email: shaaliame@yahoo.com.

Jan Hattendorf, Email: jan.hattendorf@swisstph.ch.

Said M Ali, Email: saidmali2003@yahoo.com.

Mwanaidi A Khamis, Email: mwinsimba@gmail.com.

Bobbie Person, Email: bobbieperson@gmail.com.

Fatma Kabole, Email: fatmaepi@yahoo.co.uk.

David Rollinson, Email: d.rollinson@nhm.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Gryseels B. Schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014;383:2253–2264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . WHA65.21. Elimination of schistosomiasis. Sixty-fifth World Health Assembly Geneva 21–26 May 2012 Resolutions, decisions and annexes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. pp. 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . Schistosomiasis: progress report 2001–2011 and strategic plan 2012–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Red Urine Study Group . Identification of high-risk communities for schistosomiasis in Africa: a multicountry study. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO . Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: coordinated use of anthelminthic drugs in control interventions: a manual for health professionals and programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briggs M, Chadfield M, Mummery D, Briggs M. Screening with reagent strips. Br Med J. 1971;3:433–434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5771.433-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkins HA, Goll P, Marshall TF, Moore P. The significance of proteinuria and haematuria in Schistosoma haematobium infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King CH, Sutherland LJ, Bertsch D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of chemical-based mollusciciding for control of Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters PA, Warren KS, Mahmoud AA. Rapid, accurate quantification of schistosome eggs via nuclepore filters. J Parasitol. 1976;62:154–155. doi: 10.2307/3279081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emukah E, Gutman J, Eguagie J, Miri ES, Yinkore P, Okocha N, et al. Urine heme dipsticks are useful in monitoring the impact of praziquantel treatment on Schistosoma haematobium in sentinel communities of Delta State, Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2012;122:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stete K, Krauth SJ, Coulibaly JT, Knopp S, Hattendorf J, Müller I, et al. Dynamics of Schistosoma haematobium egg output and associated infection parameters following treatment with praziquantel in school-aged children. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:298. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karanja DMS, Awino EK, Wiegand RE, Okoth E, Abudho BO, Mwinzi PNM, et al. Cluster randomized trial comparing school-based mass drug administration schedules in areas of western Kenya with moderate initial prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips Anna E., Gazzinelli-Guimaraes Pedro H., Aurelio Herminio O., Ferro Josefo, Nala Rassul, Clements Michelle, King Charles H., Fenwick Alan, Fleming Fiona M., Dhanani Neerav. Assessing the benefits of five years of different approaches to treatment of urogenital schistosomiasis: A SCORE project in Northern Mozambique. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017;11(12):e0006061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knopp S, Mohammed KA, Ali SM, Khamis IS, Ame SM, Albonico M, et al. Study and implementation of urogenital schistosomiasis elimination in Zanzibar (Unguja and Pemba islands) using an integrated multidisciplinary approach. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:930. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FS MC, Krafft JG. Schistosomiasis in Zanzibar and Pemba. Report on a mission 1 April - 7 June 1975. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savioli L, Dixon H, Kisumku UM, Mott KE. Control of morbidity due to Schistosoma haematobium on Pemba Island; selective population chemotherapy of schoolchildren with haematuria to identify high-risk localities. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:805–810. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mgeni AF, Kisumku UM, McCullough FS, Dixon H, Yoon SS, Mott KE. Metrifonate in the control of urinary schistosomiasis in Zanzibar. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:721–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knopp S, Stothard JR, Rollinson D, Mohammed KA, Khamis IS, Marti H, et al. From morbidity control to transmission control: time to change tactics against helminths on Unguja Island, Zanzibar. Acta Trop. 2013;128:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennance T, Person B, Muhsin MA, Khamis AN, Muhsin J, Khamis IS, et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis transmission on Unguja Island, Zanzibar: characterisation of persistent hot-spots. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:646. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knopp S, Person B, Ame SM, Mohammed KA, Ali SM, Khamis IS, et al. Elimination of schistosomiasis transmission in Zanzibar: baseline findings before the onset of a randomized intervention trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollinson D, Klinger EV, Mgeni AF, Khamis IS, Stothard JR. Urinary schistosomiasis on Zanzibar: application of two novel assays for the detection of excreted albumin and haemoglobin in urine. J Helminthol. 2005;79:199–206. doi: 10.1079/JOH2005305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stothard JR, Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Standley C, Van Dam GJ, Knopp S, Utzinger J, et al. An evaluation of urine-CCA strip test and fingerprick blood SEA-ELISA for detection of urinary schistosomiasis in schoolchildren in Zanzibar. Acta Trop. 2009;111:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montresor A, Crompton DWT, Hall A, Bundy DAP, Savioli L. Guidelines for the evaluation of soil-transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis at community level. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor P, Chandiwana SK, Matanhire D. Evaluation of the reagent strip test for haematuria in the control of Schistosoma haematobium infection in schoolchildren. Acta Trop. 1990;47:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(90)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldmeier H, Poggensee G. Diagnostic techniques in schistosomiasis control. A review. Acta Trop. 1993;52:205–220. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(93)90009-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knopp S, Becker S, Ingram K, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Diagnosis and treatment of schistosomiasis in children in the era of intensified control. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:1237–1258. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.844066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King CH, Bertsch D. Meta-analysis of urine heme dipstick diagnosis of Schistosoma haematobium infection, including low-prevalence and previously-treated populations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knopp S, Corstjens PL, Koukounari A, Cercamondi CI, Ame SM, Ali SM, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a urine circulating anodic antigen test for the diagnosis of Schistosoma haematobium in low endemic settings. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ephraim RK, Abongo CK, Sakyi SA, Brenyah RC, Diabor E, Bogoch II. Microhaematuria as a diagnostic marker of Schistosoma haematobium in an outpatient clinical setting: results from a cross-sectional study in rural Ghana. Trop Doct. 2015;45:194–196. doi: 10.1177/0049475515583793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibironke OA, Phillips AE, Garba A, Lamine SM, Shiff C. Diagnosis of Schistosoma haematobium by detection of specific DNA fragments from filtered urine samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:998–1001. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibironke O, Koukounari A, Asaolu S, Moustaki I, Shiff C. Validation of a new test for Schistosoma haematobium based on detection of Dra1 DNA fragments in urine: evaluation through latent class analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corstjens PLAM, Nyakundi RK, de Dood CJ, Kariuki TM, Ochola E, Karanja DM, et al. Improved sensitivity of the urine CAA lateral-flow assay for diagnosing active Schistosoma infections by using larger sample volumes. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:241. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0857-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colley DG, Binder S, Campbell C, King CH, Tchuem Tchuenté LA, N'Goran EK, et al. A five-country evaluation of a point-of-care circulating cathodic antigen urine assay for the prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:426–432. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Utzinger J, Becker SL, van Lieshout L, van Dam GJ, Knopp S. New diagnostic tools in schistosomiasis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Predicted sensitivity of reagent strips by infection intensity estimated by urine filtration. The sensitivity of the reagent strip method to detect microhaematuria increased significantly for each unit log10 egg count per 10 ml urine in children (odds ratio, OR: 4.7; 95% confidence interval, CI: 4.0–5.7, P < 0.0001) and adults (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.9–3.7, P < 0.0001). The difference of the test sensitivity between children and adults (P = 0.001) as well as the population-egg-count interaction (P = 0.002) were statistically significant. (PDF 32 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.