Abstract

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is proved to be best supportive management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) individuals. The literature claims the reduction of dyspnea, fatigue, exacerbations, and improved functional capacity and quality of life. Home-based PR is being prescribed widely than hospital-based rehab due to be less cost and ease of caregiver burden, but efficacy is usually questioned. The poor efficacy may be probably due to recurrent exacerbation and poor quality of life even after years of home rehabilitation. Telerehabilitation is an excellent rehab measure where the COPD patients exercise at his home, while expertise from the tertiary care centers monitors the rehab sessions remotely. In India, the tele-PR is at its budding state. This review shall enable the readers with the basics of telerehabilitation in comparison with the other available rehab measures and evidence in the management of COPD.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, compliance, cost, quality of life, self-management, telerehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease defines chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation.[1] This airflow limitation may be due to airway and alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gasses. The chronic airflow limitation that characterizes COPD is caused by a mixture of small airway disease (e.g., obstructive bronchitis) and parenchymal destruction (emphysema), the relative contributions of which vary from person to person and destruction of lung parenchyma. A loss of small airways may contribute to airflow limitation and mucociliary dysfunction, a characteristic feature of the disease.

The prevalence of COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases is increasing in India and worldwide. India is estimated to have 30 million COPD patients (<20% of global COPD) at present with incidence of 64.7 deaths/1,00,000 all-cause mortality.[2] With this statistics, COPD is projected to be the 3rdlargest noncommunicable disease causing mortality in 2030 by the World Health Organization.[2]

The comorbidities of COPD consist of all the physiological, mechanical, psychological alterations and disorders associated with the disease.[3,4] These comorbidities may be causal, a complication, a concurrence, or an intercurrent process to the underlying pathophysiological or pathomechanical process inherent to the pulmonary disease. Out of all of these comorbidities, the ones which are most frequently associated with COPD are hypertension, diabetes mellitus, infections, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases.[4] Dyspnea and cough characterize the progressive pathology in COPD.[5] The abundant expectoration and resulting dyspnea also result in effort intolerance and reduction in quality of life.[6] Patients with COPD have decreased exercise tolerance and experience substantial limitations in their activities of daily living which results in an inactive lifestyle compared with healthy individuals. It has been shown that high levels of physical activity (for more than 60 min a day) substantially reduced the risk of readmission to the hospital. It also has been shown to reduce the mortality rate significantly.[6]

Traditional rehabilitation system consists of hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation (HPR) which is a first-line management strategy in patients with COPD. HPR reduces breathlessness and improves exercise tolerance and health-related quality of life.[7] Usually, HPR involves supervised exercise training in a group setting and fewer self-management techniques. The training program combines aerobic exercise, strength training, respiratory exercises, and stretching with an educational program about their disease.[7] This HPR is usually an inpatient rehabilitation strategy. Almost 8%–50% of those referred to HPR never attended the program, while 10%–32% of the people who commenced the program never completed it.[8] Barriers to hospital or traditional PR's attendance and conclusion include day-to-day variations, exacerbations, hospital admissions, transportation problems, lack of support, and follow-up programs.[9] Developing new feasible rehab program to maintain regular cardiorespiratory fitness and thus extending the effect of PR is an important goal in the long-term management of COPD patients.

Telerehabilitation has the potential to support PR in the tertiary care of patients with COPD. Telerehabilitation refers to the use of information and communication technologies to provide rehabilitation services to the people remotely in their homes or other environments.[10] The primary aim is to provide equitable access to a rehabilitation program. Recent literature has depicted telerehab is as effective as supervised inpatient pulmonary rehab programs by overcoming barriers to both inpatient and home-based PR programs.[11,12,13] Ease of caregiver burden, the cost involved, compliance, exercise progression, homely environment, ease of transportation, and expertise in physical activity monitoring and counseling are the strengths of telerehabilitation.[13] Although telerehab is well established in a Western population, it is in infancy state in India. We attempted to review the evidence behind telerehabilitation, so the readers may accomplish a realistic rehab idea and set in India through telerehabilitation services shortly.

SEARCH METHODOLOGY

Our search limited to databases possessing high-quality (Q1, Q2) journals of Web of Science and Scopus with “Tele-rehabilitation,” “Mobile rehab,” “COPD,” “Rehabilitation teleservices,” and “Mobile phones” with selective Boolean operators “AND” and “OR.” The full-text articles retrieved through searches were appraised and drafted as a narrative review.

COMMUNITY-BASED PULMONARY REHABILITATION

Traditional in-house or inpatient supervised rehabilitation programs are proved to be effective in improving functional capacity, breathlessness, ADLs, and quality of life.[7] However, the cost, accessibility, caregiver stress, and time consumption are still earmarked as the barriers of inpatient PR.[14,15] Further hospital-acquired infections pose the risk of frequent exacerbations and unwanted hospitalizations in a stable patient receiving institution-based supervised PR program.[8,15] Community PR is an efficient alternative to the current traditional in-house hospital-based PR.[8]

Community fitness centers neighboring pulmonary disabled patient's home in a nonhealth-care setting with two or three fitness consultants may serve as an efficient rehab setup. The pulmonary rehab specialist shall train the fitness specialists in assessing the lifestyle behavioral modification, patient-centered outcomes such as walk and step tests, exercise dose-response, oxygen/nutritional supplementation, and progression. Despite accessibility to these community-based fitness centers, compliance and expertise are quantified by the recent research findings.[8,16] Still, the caregiver and economic burden remain the conventional barriers of community-based PR (CPR). Even in developed countries, traditional institutional-based PR and CPR services are greatly underutilized due to inaccessibility, caregiver issues, transportation, and infections.[17]

HOME-BASED PULMONARY REHABILITATION

After the CPR, the emphasis is greatly placed on long-term physical activity practice and compliance at home to the rehabilitation and self-practices; COPD patients have learned from hospital and community centers. The long-term benefits of an outmoded institution-based PR remain controversial because the transfer of the same pulmonary rehab practices at the home remains poor.[14] Home-based PR (HPR) is also proved to improve dyspnea, functional capacity, ADL ability, fatigue, sleep, depression, and quality of life.[18] HPR is well marked for its simplicity, less expertise, cheap, and convenient. Further caregiver burden and infections during travel or institutional stay are avoided in home-based rehabilitation. However, HPR has few setbacks such as lack of expertise in monitoring, assessing, and exercise dosing. Myriad evidence stated that the achieved benefits of improvement dyspnea, fatigue, and functional capacity in the 1stweeks of training were not maintained at the end of 12 weeks of training.[18] The poor compliance may be due to the failure of a caregiver to recognize the ADL difficulties or physical activities and exercise dose quantification. The poor compliance and resulting inefficacy of home-based pulmonary rehab are proved in a recent survey that 11% of proxies can identify the self-care and leisure activity problem in COPD patients.[19] In this context, it is the responsibility of health-care systems to minimize the barriers to the accessibility and long-term compliance to HPR. Hence, there emerged a need for expertise input or distance monitoring through advanced technology in increasing amenability and exercise dosing during HPR.

TELEREHABILITATION

Telerehabilitation shall be defined as “telehealth application using telecommunication technologies to administer the rehabilitation services so that patient receives supervised rehabilitation at home, while the rehab specialist is at hospital.”[20] Respiratory telerehabilitation (RTR) involves reinforcement of exercise dosing, follow-up, physical activity, nutritional and psychological counseling through telephone, social media such as E-mail, Twitter, and Facebook, activity monitors communicating to the central hospital servers, and video conferencing to the pulmonary disabled patients.

INSTRUMENTATION AND WORKING OF TELEREHABILITATION IN CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

As the name signifies, telerehabilitation is the administration of telecommunication technology to dispense rehabilitation services remotely. Earlier researchers employed E-mails, phone calls, Facebook, and Twitter as a part of telerehabilitation services to pulmonary rehab patients at home for improving compliance to the exercise program.[21] However, as the technology advanced, real-time video conferencing, global positioning system built with accelerometers, and pedometers or virtual imagery provide the step count, physical activity, and energy expenditure of the COPD patients.[22] Step count and physical activity compliance has been correlated with mortality and quality of life in COPD patients.[23] Real-time monitoring such as dyspnea, talk test, walk distance, physical activity quantification, energy expenditure, adverse events such as falls, chest pain, or leg fatigue, and functional capacity can be measured and archived for progression with RTR.

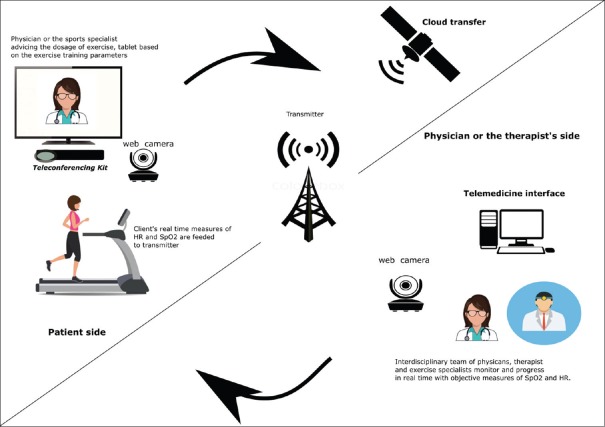

The typical telecommunication network needed for telerehabilitation is depicted in Figure 1. The telerehab network components are a patient workstation, rehab therapist workstation, and the Internet speed of 8 Mbps/s for streamlining the video conferencing.

Figure 1.

Typical components of respiratory telerehabilitation

This simulated supervised pulmonary rehab session consists of monitoring the intensity of exercise, saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure. Any advert events shall be promptly observed, and exercise or nutritional counseling shall be given promptly. The exercise adherence shall be monitored through the number of sessions attended, exercise duration, intensity, and frequency of exercise sessions.[22] This exercise adherence shall be transferred to real-life ADL such as cooking, industrial activities such as pulling, pushing, lifting, child rearing, playing or leisure-time activities through teleconferencing, and functional simulation. At the end of 8–12 weeks of supervised telerehab through teleconferencing, the vocational and functional training shall transfer to real-time household functional and occupational activities.

THE EVIDENCE BEHIND THE TELEREHABILITATION IN CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

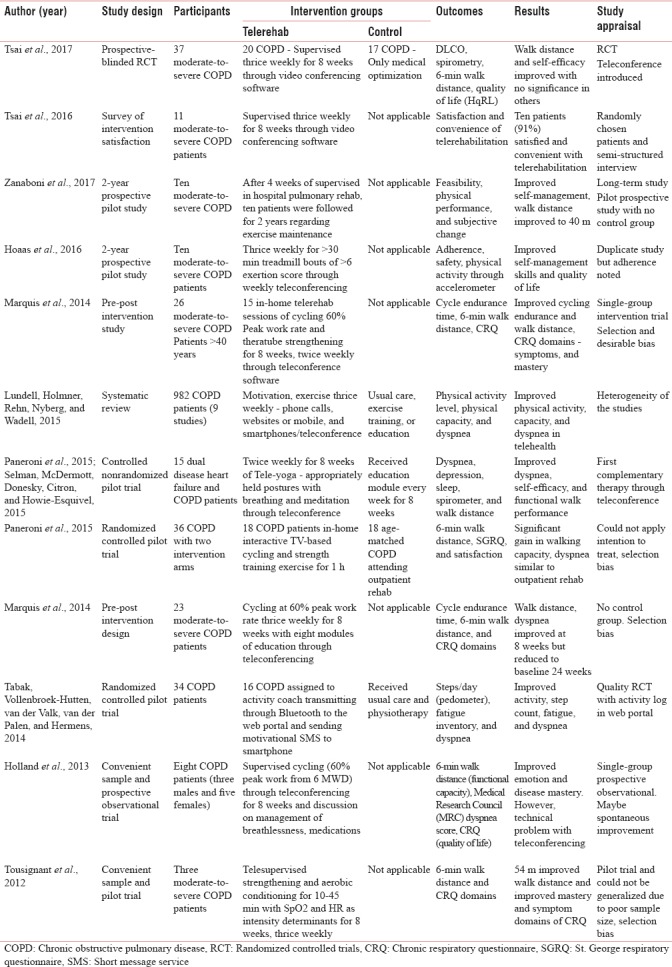

Abundant evidence is put forth recently to establish the benefits and impact of telerehabilitation in COPD patients.[12,14,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] Recent studies had confirmed the safety, the feasibility of telerehabilitation yielding benefits similar to institutional-based rehabilitation such as reduced dyspnea, improved functional capacity, reduced morbidity, and quality of life.[12,18,19,20,21,22,23,25] Further, the caregiver burden and accessibility are the greater advantages of the telerehabilitation at home. The major benefits of telerehabilitation are improved functional capacity, reduced cost, caregiver stress, and higher compliance to the physical activity or exercise program. Further, it provides ease at home and safety concerns be reduced increasing compliance and thereby maintaining the benefits of institutional or CPR services. Similar to traditional HPR or CPR, several researchers have found the improvement in dyspnea, leg fatigue, walk distances, lung function, reducing hospitalization for exacerbation, and reducing mortality and morbidity associated with their pulmonary disorders. Table 1 elaborates the recent studies pertained to telerehabilitation in COPD.

Table 1.

Evidence of telerehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CONCLUSION

Tele-PR shall be effective in improving dyspnea, functional capacity, and quality of life in COPD patients. TPR is proved to be more cost-effective, expertise guided, simple like traditional, or CPR. In future, TPR may be an efficient alternative to routinely administered HPR and CPR.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author (BC) wishes to thank his HOD, Dr. Fiddy Davis PhD PT Associate Professor, for his moral support and intellectual inputs in manuscript drafting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes PJ. GOLD 2017: A new report. Chest. 2017;151:245–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koul PA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Indian guidelines and the road ahead. Lung India. 2013;30:175–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.116233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouellette DR, Lavoie KL. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of cognitive and psychiatric disorders in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:639–50. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S123994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malerba M, Olivini A, Radaeli A, Ricciardolo FL, Clini E. Platelet activation and cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:885–91. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1149054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samanta S, Hurst JR. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Aetiology, pathology, physiology and outcome. Medicine. 2016;44:305–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alahmari AD, Kowlessar BS, Patel AR, Mackay AJ, Allinson JP, Wedzicha JA, et al. Physical activity and exercise capacity in patients with moderate COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:340–9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01105-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroff P, Hitchcock J, Schumann C, Wells JM, Dransfield MT, Bhatt SP, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease independent of disease burden. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:26–32. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201607-551OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecins N, Landers H, Jenkins S. Community-based pulmonary rehabilitation in a non-healthcare facility is feasible and effective. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14:3–10. doi: 10.1177/1479972316654287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown AT, Hitchcock J, Schumann C, Wells JM, Dransfield MT, Bhatt SP, et al. Determinants of successful completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:391–7. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S100254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kizony R, Weiss PL, Harel S, Feldman Y, Obuhov A, Zeilig G, et al. Tele-rehabilitation service delivery journey from prototype to robust in-home use. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1532–40. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1250827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanaboni P, Hoaas H, Aarøen Lien L, Hjalmarsen A, Wootton R. Long-term exercise maintenance in COPD via telerehabilitation: A two-year pilot study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:74–82. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15625545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai LL, McNamara RJ, Moddel C, Alison JA, McKenzie DK, McKeough ZJ, et al. Home-based telerehabilitation via real-time video conferencing improves endurance exercise capacity in patients with COPD: The randomized controlled teleR study. Respirology. 2017;22:699–707. doi: 10.1111/resp.12966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland AE, Cox NS. Telerehabilitation for COPD: Could pulmonary rehabilitation deliver on its promise? Respirology. 2017;22:626–7. doi: 10.1111/resp.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayton C, Clark A, Olive S, Browne P, Galey P, Knights E, et al. Barriers to pulmonary rehabilitation: Characteristics that predict patient attendance and adherence. Respir Med. 2013;107:401–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corhay JL, Dang DN, Van Cauwenberge H, Louis R. Pulmonary rehabilitation and COPD: Providing patients a good environment for optimizing therapy. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:27–39. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S52012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alsubaiei ME, Cafarella PA, Frith PA, McEvoy RD, Effing TW. Barriers for setting up a pulmonary rehabilitation program in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11:121–7. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.180028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marquis N, Larivée P, Saey D, Dubois MF, Tousignant M. In-home pulmonary telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A Pre-experimental study on effectiveness, satisfaction, and adherence. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:870–9. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu XL, Tan JY, Wang T, Zhang Q, Zhang M, Yao LQ, et al. Effectiveness of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rehabil Nurs. 2014;39:36–59. doi: 10.1002/rnj.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakken N, Janssen DJ, van den Bogaart EH, van Vliet M, de Vries GJ, Bootsma GP, et al. Patient versus proxy-reported problematic activities of daily life in patients with COPD. Respirology. 2017;22:307–14. doi: 10.1111/resp.12915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paneroni M, Colombo F, Papalia A, Colitta A, Borghi G, Saleri M, et al. Is telerehabilitation a safe and viable option for patients with COPD? A feasibility study. COPD. 2015;12:217–25. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2014.933794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNamara RJ, Elkins MR. Home-based rehabilitation improves exercise capacity and reduces respiratory symptoms in people with COPD (PEDro synthesis) Br J Sports Med. 2016;51:206–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoaas H, Andreassen HK, Lien LA, Hjalmarsen A, Zanaboni P. Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A mixed methods study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, Garcia-Aymerich J, ZuWallack R, Troosters T, et al. An official European respiratory society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1521–37. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marquis N, Larivée P, Dubois MF, Tousignant M. Are improvements maintained after in-home pulmonary telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Int J Telerehabil. 2014;6:21–30. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2014.6156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tousignant M, Marquis N, Pagé C, Imukuze N, Métivier A, St-Onge V, et al. In-home telerehabilitation for older persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A Pilot study. Int J Telerehabil. 2012;4:7–14. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2012.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mesquita R, Nakken N, Janssen DJ, van den Bogaart EH, Delbressine JM, Essers JM, et al. Activity levels and exercise motivation in patients with COPD and their resident loved ones. Chest. 2017;151:1028–38. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]