Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to describe the experiences of other countries regarding the status of pediatric palliative care in the field of symptom management and to compare it with the current status in Iran to achieve an appropriate level of symptom management for children with cancer.

Materials and Methods:

This is a comparative study. The research population includes the palliative care systems of Jordan, England, Australia, and Canada, which were ultimately compared with Iran's palliative care system.

Results:

The results showed that in the leading countries in the field of palliative care, such as Australia and Canada, much effort has been made to improve palliative care and to expand its service coverage. In the UK, as a pioneer in the introduction of palliative care, a significant portion of clinical performance, education and research, is dedicated to childhood palliative care. Experts in this field and policymakers are also well aware of this fact. In developing countries, including Jordan, palliative care is considered a nascent specialty, facing many challenges. In Iran, there is still no plan for providing these services coherently even for adults.

Conclusion:

Children with cancer experience irritating symptoms during their lives and while they are hospitalized. Regarding the fact that symptom management in developed countries is carried out based on specific and documented guidelines, using the experiences of these successful countries and applying them as an operational model can be useful for developing countries such as Iran.

Keywords: Cancer, children, palliative care, symptom management

INTRODUCTION

One of the challenges in nursing care is giving care to children with cancer.[1,2] Cancer is one of the main causes of child mortality in developed and developing countries.[3] The incidence rate of cancer in children and adolescents is reported to be approximately 15/100,000.[2] It is the second leading cause of death in children under 14 in Iran.[4]

Many children with life-threatening diseases suffer from uncomfortable symptoms not only through their final days but also during the illness.[5] Cancer and the treatment procedure associated with it, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, result in various problems for children,[2,6,7,8] such as shortness of breath, fatigue, digestive issues, and changes in sleep-wake patterns as some of the most commonly reported symptoms.[9,10] The presence of symptoms and complications of the disease and the treatment procedures, along with the high costs of treatment, as well as psychological and social side effects and changes caused by the disease, necessitates comprehensive care in the form of “supportive and palliative care” for a child and his/her family.[11,12] Palliative care is a kind of comprehensive care, seeking to manage all the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of the children and their families. For optimal use of supportive care, treatment centers must have a proper understanding of the symptoms and their range in terminal diseases, especially cancer, such as nausea, malaise, weakness, and depression.[13]

In 2014, the World Health Organization acknowledged that there was limited access to supportive and palliative care in many parts of the world,[14] so the provision of these services in the Middle Eastern countries is regarded as a necessity.[15] The high incidence rate of childhood cancer, and consequently the mortality associated with it, is one of the main reasons for the necessity of palliative care in these countries.[16] There are no palliative care centers for children in Iran. In addition, the caregivers' knowledge is insufficient regarding palliative care and its philosophy, symptom management, and provision.[13,17,18]

Considering the problems that children with cancer and their families may face, besides the chronic nature of this disease that affects all the stages of the child's growth and development, symptom management and controlling the signs of the disease are regarded as the requirements of the health system.[19,20]

Since one of the best methods to improve the quality of care is care audit, assessing the current status of sign and symptom management in Iran and comparing it with the experiences of other countries achieving a proper status in the same field can be a big step toward developing this kind of care in Iran. This study aims to describe the structure and procedure of symptom management in children with cancer in Jordan, England, Australia, and Canada and to compare it with that of Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a comparative study.[21] A comparative study is a method of study that combines phenomena and analyzes them to find the points of differentiation and similarity. These studies generally involve three processes of description, comparison, and conclusion with the aim of describing, explaining subscriptions and often differences, identifying these phenomena, and arriving at interpretations and possibly new generalizations.[22] For this purpose, due to the necessity of comparing the conditions of the countries to determine the distance between children's palliative care in Iran and the situation in the countries of the region and advanced countries, the use of comparative methodology was used to achieve the research goal. The research population includes the palliative care systems of Jordan (situated in the same region as Iran, with similar health conditions), England (providing palliative care for children as a comprehensive approach in physical, emotional, social, and spiritual aspects), Australia (developing caregiving models in creative and specific ways), and Canada (with a significant improvement in clinical, research, and educational care services in children's palliative care over the last 20 years), which were ultimately compared with Iran's palliative care system. This comparison, according to a study by the International Observatory on End of Life Care, is conducted to assess palliative care in 234 countries. According to the results of this survey, around 160 countries are actively providing palliative care or developing a framework for establishing a system for such services. England, Canada, and Australia are in Group B4. In this group, specialist palliative care services are offered to the patients at the final stages of life and their families including symptomatic treatment and pain management and end-of-life plans such as mourning and hospice services. Experts and public are well aware of palliative care and have unlimited access to morphine and all other types of strong painkillers. Official palliative care training centers are developed in these countries, and there are also national palliative care organizations as well as academic communications with other universities.[22,23]

Jordan is known to be one of the countries with Level 3 palliative care. Limited training has been provided for experts, but other significant fields such as the national palliative care strategy, medical supplies policy, and large-scale training are developing. In these countries, home care is the most common type of palliative care provision.[24] In 2011, Iran was promoted to Group A3. In this group, palliative care is developed only partially and is not well supported. Funding depends on the financial support of a single source (such as government) to a great extent, while nongovernmental organizations do not play a significant role.[22,23]

To gather the necessary data on the status of palliative care structures and symptom management, initial studies were conducted on palliative care programs in the field of symptom management in children with cancer, by referring to the databases affiliated with reputable centers such as King Hussein Cancer Center, Cancer Care Ontario (CCO), the Australian Government of Department of Health, the European Association for Palliative Care, through using the following keywords: cancer, guide to palliative care, cancer care in children, palliative care, pediatric cancer, cancer management, pediatric cancer management, and pediatric care programs.

After accessing the international-codified models of palliative care, Iran's palliative care program was evaluated too, by referring to children's service centers and their databases.

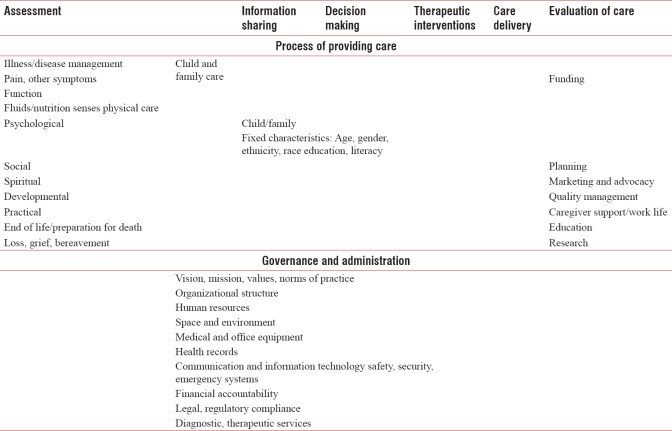

The conceptual framework of the current study is based on the Square of Care. In this model, the child and his/her family are placed at the center of the square as the care unit. Clinical activities performed in children's palliative care consist of two parts. Providing care for the child and his/her family (disease management), physical care (pain and symptom management) as well as psychosocial, spiritual, social, evolutionary, practical, and end-of-life care, and mourning care are placed on the left side of the square. The procedure of care provision (steps to be taken by health experts to provide different phases of care include review, decision-making, and care provision) is located on top of the square. Practical activities that support effective child palliative care include two parts: supportive activities (planning, marketing, education, and research) on the right side of the square and administering and management (resources, information technology, and organizational structure) on the bottom of the square [Figure 1].[25]

Figure 1.

Square of care

The current study aimed at studying the structure of palliative care and symptom management through data analysis by comparing the similar and different aspects of palliative care systems in the selected countries and in Iran in the aforementioned fields.

RESULTS

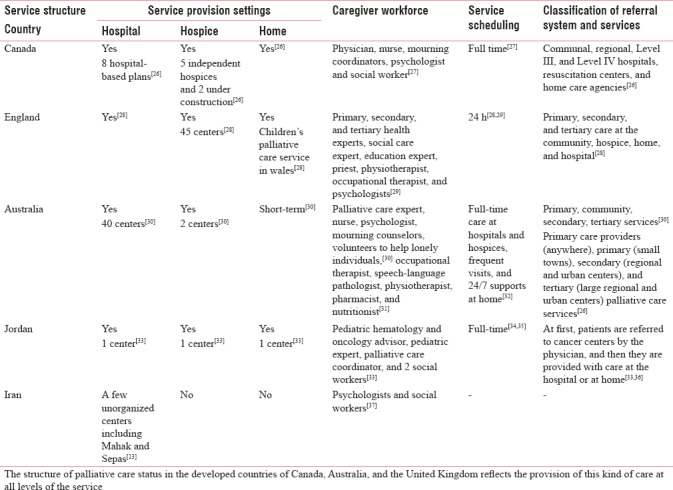

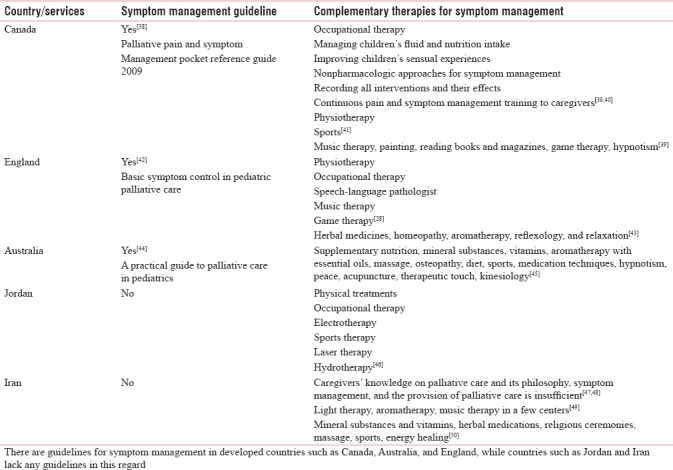

After examining the status of palliative care in Iran and in Canada, Australia, England, and Jordan in the intended fields, the results are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 shows the structural status of palliative care service provision. Table 2 presents the results of the comparisons between the statuses of palliative care provision process in symptom management. Symptom management means the children and their families having access to the proper treatment for the disease, the information about the impact of proper treatment on the quality of life, and the necessary support needed to help overcome the barriers.[51]

Table 1.

The structure of palliative care service provision in the field of symptom management

Table 2.

The process of palliative care service provision in the field of symptom management

DISCUSSION

Considering the increasing rate of childhood cancer in developing countries and the importance of improving the patients and their families' quality of life, palliative care has become very important.[13,52] To this end, utilizing other countries' experiences in the field of palliative care and cancer symptom management can help improve the process of providing this service for children. Therefore, the present study was conducted to compare symptom management status in children with cancer in Iran and in the selected countries.

A brief review on the findings of the present study shows that in the leading countries in the field of palliative care, such as Australia and Canada, despite the large area and the low rates of child mortality, much effort has been made to improve palliative care and to expand its service coverage. However, there are still numerous challenges, such as high immigration rate and high population of care receivers with various social, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds that require variety in the provision of childcare.[22] In the UK, as a pioneer in the introduction of palliative care, a significant portion of clinical performance, education and research, is dedicated to childhood palliative care. Experts in this field and policymakers are also well aware of this fact.[53,54] However, due to the lack of sufficient resources at National Health Center (NHS), evaluating regional necessities is very important to answer the children and their families' needs and to design a proper organizational structure in this country.[28] In developing countries, including Jordan, palliative care is considered a nascent specialty, facing many challenges.[34] In Iran, there is still no plan for providing these services coherently, even for adults.[13] However, in 2014, the World Health Organization emphasized the integration of palliative care into care chain and considered providing these services in the Middle East a necessity.[14,15]

In the present study, to achieve better understanding of the structural status of palliative care services, first of all, care provision settings, human resources, scheduling and classification of services, and referral systems in the selected countries were studied.

In the UK, 258 services provide palliative care for children, regarding care provision settings.[24] The three major settings for providing palliative care are the community, the hospice, and the hospital. However, the majority of the target populations spend most of their time either at home or at school. However, the mortality rate of these children is still high in hospitals.[28] In Australia, over the last 20 years, palliative care has been being provided in all the health-related areas including child care.[55] Children are given care in high-quality hospitals, but the community-based services are limited. Home care services support the children who need to be hospitalized for a short time. In this country, there are insufficient social and specialized infrastructures to provide home care for children.[30] Throughout Canada, childcare services are provided in community, Level III, and Level IV centers, regional hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and home care agencies. However, due to the inaccessibility of these services in many regions of Canada, there are also hospital and hospice programs, which are used by <5% of the children needing palliative care.[26] Despite the existence of hospices in England, Canada, and Australia, there is still a tendency to provide hospitalization and specialist services in hospitals.[56] In Jordan, palliative care is provided properly in the form of outpatient clinics, daily care to manage symptoms, and giving consultation to the patients and their families. Home care is provided for cancer patients at King Hussein Cancer Center; however, due to lack of nurses and social workers for visiting patients, this kind of service has limitations for children, and only a few children access it. Only in Oman, the capital of Jordan, a private clinic offers home care programs with special nurses along with doctors and an interdisciplinary team.[33] In Iran, care services for incurable patients, especially those in their final days, are provided by family members. Although hospitals accept these patients and provide them with care, the idea of palliative care is still unknown and the provided services are very restricted.[13] In Iran, care services for cancer patients are generally hospital based.[36] Places that provide specialized home care are very rare, and there are no centers such as hospices. Hospitals provide palliative care at the end-of-life stage.[57,58] In Iran, the lack of medical centers such as outpatient clinics and hospices for symptom management in children with cancer results in long-term hospitalizations and expensive medications and can have negative effects on the child and his/her family.

The second area of discussion in the present study deals with investigating the status of palliative care provision process in symptom management. To this end, the presence or the lack of symptom management guidelines as well as supplementary cares for symptom management were evaluated. In many countries, symptom management guidelines are designed based on their resources, plans, and goals of the health system.[59] The development of these guidelines requires the evidence of the impact of these interventions. These impacts may appear as cost-effectiveness, higher quality of life, and satisfaction.[60,61]

The results of the present study regarding the presence of symptom management guidelines showed that CCO in Canada has developed specific guidelines for palliative care.[62] Their main goal is to maximize children and their families' comfort.[39] In the UK and Australia, a series of processes and instructions derived from international guidelines are used to provide care for cancer patients and manage their symptoms.[39,32,40,63] For example, in Australia, the symptom management care program includes receiving important information on child's symptoms. With proper support, symptoms are well managed at home and families will be well-informed about when and whom they can contact to ask their questions about home care.[32] Although employees working in the palliative care sector have adequate skills in symptom management, family care, and death management, they do not have enough experience with children's challenges.[30] In Canada and England, symptom management is carried out through gathering information from different sources by a team.[42]

However, it seems that the accessibility of symptom management guidelines is insufficient in some countries. In Jordan, it is estimated that >20% of the patients diagnosed with cancer are in advanced stages of the disease, and most of them are incurable at their initial visit. Palliative care is the only option to reduce their pain and suffering.[34] In this country, there is no media or public support for palliative care and educating families and patients in this regard. King Hussein Cancer Center is trying to create a booklet and hold a specialist training course for nurses in symptom management to deal with the common symptoms that patients with cancer suffer from.[33] In Iran, palliative care is one of the requirements of the health system, particularly considering the high mortality rate and the need for providing specialist treatments such as treatment and symptom management. There are still no plans to provide these services in Iran, compared with the available primary treatments. The care centers do not provide medical and palliative care services for patients with acute diseases and their families. Patients and their families are constantly worried and anxious at the time of seeking such care services since the treatment centers either refuse to do so or are incapable of providing timely and adequate services. To use supportive care optimally, the treatment centers must have a proper understanding of the disease symptoms.[13]

Supplementary and alternative care include a diverse range of medical and health services, uncommon products, and methods, such as dietary supplements, herbal remedies, and spiritual therapy, which are reported to be provided for 84% of children with cancer. In the developed countries such as Canada, England, and Australia, supplementary care is included in children's palliative care programs. The results of a study conducted in Canada, in 2013, showed that the most commonly consumed supplements for children with cancer are multi-vitamin and Vitamin C and the most common methods had faith (for example, praying for your health or others praying for you) and massage. According to the study, the main reason for not using these treatments was the lack of knowledge in this field.[64] Moreover, a review study in England showed that almost one-third of the cancer patients were provided with supplementary care from the time of diagnosis, and the challenge which cancer patients may face in this regard is the possibility of causing harm in some of these methods.[43] In Jordan, at King Hussein Cancer Center, some supplementary care is offered along with the main cancer treatments.[65] In this regard, in 2013, a study was conducted in this center by Al-Omari et al. to assess the perception and attitude of Jordanian doctors toward complementary medicine. The results showed that the majority of participants did not consider these kinds of medications to be based on evidence, and they regarded it as equal to herbal remedies which do some harm. The doctors in this center had very low knowledge and much interest in learning complementary medicine. Therefore, to formally apply these kinds of care, it is necessary to include it in the curriculums. In Iran, children with cancer are provided with many complementary medications along with chemotherapy.[66] According to Bordbar et al., the most common supplement used by families was zinc pills and the most common complementary practice was praying. Since most families do not inform the physician in case of using supplements, there is the possibility of their negative impact on the main treatment of cancer. Hence, caregivers must have adequate knowledge in this regard, and physicians must dedicate sufficient time to discuss the risks and the benefits of complementary therapies.[67]

With regard to the priority of palliative care services at various levels by the World Health Organization, the Iranian Ministry of Health has recently been designing a palliative care system with prioritization of national cancer control programs, the establishment of a palliative care workforce, and the use of resources and experts opinions.[68] According to the need assessment for palliative care in Iran in 2018, four essential needs including “academic education planning,” “workforce education,” “public awareness,” and “patient and caregiver empowerment” revealed that these should be understood, analyzed, and reviewed.[50] Some strategies, including the provision of a palliative care curriculum for all medical groups particularly for nursing students, development of a multidisciplinary palliative care curriculum,[13,69] appropriate training based on the needs of stakeholders, as well as the organization of educational resources, integration of palliative care with the health system, development of national strategies, and provision of healthcare education, especially for volunteers, have been suggested. These efforts will succeed when used in other successful countries.[50] Further, four factors influencing palliative care policy included context (political, social, and structural feasibility), content (target setting), process (attracting stakeholder participation, standardization of care, and education management), and actors (the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, health-care providers, and volunteers).[70] Regarding the fact that the use of these factors in other major successful palliative care policies as well as the design of palliative care packages for cancer patients, beginning with the support of the Ministry of Health in 2011 at the National Cancer Committee, is still ongoing progress,[71,72] the definition of executive policies in service delivery systems has not been defined in the health system of Iran yet,[57] and the design of service packages, that is a good financial policy for better health care provision,[70] and the use of standard guidelines[73,74] have been suggested. Moreover, the limited palliative care services in Iran are often lacking in clinical guidelines and are only offered based on personal experience and knowledge, but some guidelines, including spiritual services and protocol for pain, are provided in Iran and used locally in institutions.[73,74] In Iran, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education is the top level agency in charge of the health system and is responsible for planning and implementing health policies at the national level; part of this responsibility is delegated to medical science universities across the country.[70] However, due to the lack of sufficient evidence in assessing the need for palliative care services, the policymakers of the country are unaware of the necessity and priority of such services.[75,76]

CONCLUSION

Children with cancer experience irritating symptoms during their lives and while they are hospitalized. Regarding the fact that symptom management in developed countries is carried out based on specific and documented guidelines, using the experiences of these successful countries and applying them as an operational model can be useful for developing countries such as Iran.

Palliative care is provided at different levels of care in advanced countries. However, it is still a challenge to realize whether all families receive adequate help at the right time or not. To answer this question, it is necessary to conduct researches to assess the extent of family access to these types of care. It is a must to ensure that caregivers have received the required training. Due to the existence of some barriers in the process of symptom management, such as the complexity and variety of symptoms, it is necessary to identify these barriers and find strategies to overcome them.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by School of Nursing and Midwifery, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Golestan Street, Ahvaz, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all patients who participated in this study with full consent and also Mohsen Jamali and Fatemeh Jorfi, dear cardiovascular specialists in Shushtar, without the assistance and cooperation of whom this research would not have been completed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peris-Bonet R, Salmerón D, Martínez-Beneito MA, Galceran J, Marcos-Gragera R, Felipe S, et al. Childhood cancer incidence and survival in Spain. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 3):iii103–110. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong D, Hockenbry M, Vilson D. Wong's Nursing Care of Infants and Children. 9th ed. Iran: Boshra; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panganiban-Corales AT, Medina MF., Jr Family resources study: Part 1: Family resources, family function and caregiver strain in childhood cancer. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2011;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1447-056X-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashani F. Spiritual intervention effect on quality of life improvement in mothers of children with cancer. J Med Jurisprud. 2012;4:127–49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klick JC, Hauer J. Pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2010;40:120–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Childhood Cancer Organization. Childhood Leukemias. 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.acco.org/types-of-childhood-cancer/childhood-leukemias/

- 7.Cohen H, Bielorai B, Harats D, Toren A, Pinhas-Hamiel O. Conservative treatment of L-asparaginase-associated lipid abnormalities in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:703–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Cancer Society. Childhood Leukemia. Signs and Symptoms of Childhood Leukemia. 2016. [Last Revised on 2016 Feb 03 and Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org .

- 9.Shaw TM. Pediatric palliative pain and symptom management. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41:329–34. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20120727-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David A, Banerjee S. Effectiveness of “palliative care information booklet” in enhancing nurses' knowledge. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:164–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.73647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Connor SR. Referring a patient and family to high-quality palliative care at the close of life: “We met a new personality. With this level of compassion and empathy”. JAMA. 2009;301:651–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mardanihamooleh M, Borimnejad L, Seyedfatemi N, Tahmasebi M. Palliative care of pain in cancer: Content analysis. Anesthesiol Pain. 2013;4:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Palliative care in the Islamic Republic of Iran. In: Silbermann M, editor. Palliative Care to the Cancer Patient: The Middle East as a Model for Emerging Countries. New York: Nova Scientific Publisher; 2014. p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centeno C, Lynch T, Garralda E, Carrasco JM, Guillen-Grima F, Clark D, et al. Coverage and development of specialist palliative care services across the World Health Organization European region (2005-2012): Results from a European Association for Palliative Care Task Force Survey of 53 countries. Palliat Med. 2016;30:351–62. doi: 10.1177/0269216315598671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, Nestoros S, Pitsillides B, Charalambous H, et al. Palliative cancer care in Middle Eastern countries: Accomplishments and challenges. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):15–28. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silbermann M, Fink RM, Min SJ, Mancuso MP, Brant J, Hajjar R, et al. Evaluating palliative care needs in Middle Eastern countries. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:18–25. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Palliative Care to the Cancer Patient: The Middle East as a Model for Emerging Countries. USA: Nova Science; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouhollahi MR, Saghafinia M, Zandehdel K, Motlagh AG, Kazemian A, Mohagheghi MA, et al. Assessment of a hospital palliative care unit (HPCU) for cancer patients; A conceptual framework. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:317–27. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.164901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asghari-Nekah S, Jansouz F, Kamali F, Taherinia S. The resiliency status and emotional distress in mothers of children with cancer abstract. J Clin Psychol. 2015;1:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobasher M, Nakhaee N, Tahmasebi M, Zahedi F, Larijani B. Ethical issues in the end of life care for cancer patients in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:188–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smelser NJ. On comparative analysis, interdisciplinarity and internationalization in sociology. Int Sociol. 2003;18:643–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:1094–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright M, Wood J, Lynch T, Clark D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global view. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:469–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Cancer Research Network. Establishment of a National Comprehensive Nursing and Palliative Care Program. Deputy of Health Department of Cancer Treatment: Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: :http://cri.tums.ac.ir/wp -content/uploads/2017/09/cancer_pallative_care.pdf .

- 25.Ferris FD, Balfour HM, Bowen K, Farley J, Hardwick M, Lamontagne C, et al. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care: Based on National Principles and Norms of Practice. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widger K, Cadell S, Davies B, Siden H, Steele R. Pediatric palliative care in Canada. In: Knapp C, Fowler-Kerry S, Madden V, editors. Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives. London, New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widger K, Davies D, Rapoport A, Vadeboncoeur C, Liben S, Sarpal A, et al. Pediatric palliative care in Canada in 2012: A cross-sectional descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:E562–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba M, Hain R. Paediatric palliative care in the United Kingdom. Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives. London, New York: Springer, Dordrecht Heidelberg; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. End of Life Care for Infants, Children and Young People with Life-Limiting Conditions: Planning and Management. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hynson J, Drake R. Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives. London, New York: Springer, Dordrecht Heidelberg; 2012. Paediatric palliative care in Australia and New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Currow D. Australia: State of palliative service provision 2002. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:170–2. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palliative Care Australia. Journeys: Palliative care for children and teenagers. 2nd ed. developed by Palliative Care Australia with funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing 2010. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://palliativecare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2015/04/Journeys-2010-full-document.pdf .

- 33.Al-Rimawi HS. Pediatric oncology situation analysis (Jordan) J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(Suppl 1):S15–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318249aac1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdel-Razeq H, Attiga F, Mansour A. Cancer care in Jordan. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2015;8:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bingley A, Clark D. A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East cancer consortium (MECC) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier DE, McCormick E, Arnold R, Savarese D. Benefits, Services, and Models of Subspecialty Palliative Care. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 May 21]. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/benefits-services-and-models-ofsubspecialty-palliative-care .

- 37.The Mahak Society to Support Children Suffering from Cancer, Worker. 2017. [Last update on 2018 Jun 30 and Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.mahak-charity.org/main/index.php/fa/about-mahak/mahak-parts/supporting-services/wahtarereinforceactivities .

- 38.Palliative Pain & Symptom Management Pocket Reference Guide. London, Ontario, Canada: Palliative Pain & Symptom Management Consultation Program, Southwestern Ontario; 2009. Palliative Care Experts in the Erie St. Clair and South West LHINS. [Google Scholar]

- 39.European Association for Palliative Care. Countries that Participate in the Taskforce Spiritual Care. 2016. [Last accessed on 2018 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.eapcnet.eu/themes/clinicalcare/spiritualcareinpalliativecare.aspx .

- 40.BC Cancer Agency. Breast Cancer Guidelines. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/professional-resources/cancer-management-guidelines/breast .

- 41.Assessment and Management of Pain. Toronto: Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario; 2013. Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jassal S. The Rainbows Children Hospice Guidelines. 8th ed. England: Myra Johnson and Susannah Woodhead, ACT; 2011. Basic symptom control in pediatric palliative care. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posadzki P, Watson L, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine-use by UK cancer patients: A systematic review of surveys. J Integr Oncol. 2012;1:102. [Google Scholar]

- 44.A Practical Guide to Palliative Care in Paediatrics. Sydney, Australia: 2014. Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Complementary Therapies. Australia: The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: https://www.rch.org.au/rch_palliative/for_health_professionals/Complementary_therapies/

- 46.King Hussein Cancer Foundation/King Hussein Cancer Center. Rehabilitation & Physical Therapy. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.khcc.jo/section/rehabilitation-physical-therapy .

- 47.Madjd Z, Afkari M, Goushegir A, Baradaran H. The concept of palliative care practice among Iranian general practitioners. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2012;2:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sajjadi M, Rassouli M, Khanalimojen L. Nursing education in palliative care in Iran, S4: S4-001. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;S4:S4–001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Society to Support Children Suffering from Cancer. Psychological Services for Children. 2018. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: https://www.mahak-charity.org/main/index.php/fa/mahak-services/my-child-is-a-cancer-patient/psychology/childrenpsychologicalservices .

- 50.Ansari M, Rassouli M, Akbari ME, Abbaszadeh A, Akbari Sari A. Educational needs on palliative care for cancer patients in Iran: A SWOT analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2018;6:111–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.BC Children's Hospital Division of Pediatric Oncology/Hematology/BMT. Pediatric Oncology Palliative Care Guidelines. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayati H, Kebriaeezadeh A, Nikfar S, Akbari Sari A, Troski M, Molla Tigabu B. Treatment costs for pediatrics acute lymphoblastic leukemia; comparing clinical expenditures in developed and developing countries: A review article. Int J Pediatr. 2016;4:4033–41. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Palliative care in Iran: Moving toward the development of palliative care for cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:240–4. doi: 10.1177/1049909114561856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abrahm JL. Advances in palliative medicine and end-of-life care. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:187–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050509-163946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Australian Government of Department of Health. The National Palliative Care Strategy. 2010. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/ageing-npcs-2010-toc .

- 56.Klinger CA, Howell D, Zakus D, Deber RB. Barriers and facilitators to care for the terminally ill: A cross-country case comparison study of Canada, England, Germany, and the United States. Palliat Med. 2014;28:111–20. doi: 10.1177/0269216313493342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Cancer care in countries in transition: The Islamic Republic of Iran. In: Silbermann M, editor. Palliative Care in Countries & Societies in Transition. New York: Springer; 2016. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-22912-6. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mojen LK, Rassouli M, Eshghi P, Sari AA, Karimooi MH. Palliative care for children with cancer in the Middle East: A Comparative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:379–86. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_69_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caruso Brown AE, Howard SC, Baker JN, Ribeiro RC, Lam CG. Reported availability and gaps of pediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of published data. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1369–83. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woitha K, Van Beek K, Ahmed N, Hasselaar J, Mollard JM, Colombet I, et al. Development of a set of process and structure indicators for palliative care: The Europall project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:381. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knapp C, Madden V. Conducting outcomes research in pediatric palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:277–81. doi: 10.1177/1049909110364019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cancer Care Ontario. Palliative Care Program. 2015. [Last updated on 2015 Dec 07 and Last accessed on 2018 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.cancercare.on.ca/cms/one.aspx?portalId=1377&pageId=8706.

- 63.Chambers L, Dodd W, McCulloch R, McNamara-Goodger K, Thompson A, Widdas D. A Guide to the Development of Children's Palliative Care Services. 3rd ed. England: Association for Children's Palliative Care; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valji R, Adams D, Dagenais S, Clifford T, Baydala L, King WJ, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine: A survey of its use in pediatric oncology. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:527163. doi: 10.1155/2013/527163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.King Hussein Cancer Foundation/King Hussein Cancer Center. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.khcc.jo .

- 66.Al-Omari A, Al-Qudimat M, Abu Hmaidan A, Zaru L. Perception and attitude of Jordanian physicians towards complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in oncology. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bordbar M, Kamfiroozi R, Fakhimi N, Jaafari Z, Zarei T, Haghpanah S. Complementary and alternative medicine in pediatric oncology patients in South of Iran. Iran J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;6:216–77. [Google Scholar]

- 68.PACT. Atomic Energy Agency PACT Program Experts' Recommendations and the World Health Organization on Cancer Control Program in Iran. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.login.research.ac.ir/Repository/UploadSenderSubSystem/32416bdd-f3f5-4117-a0b3-6a295bf3e1d1.pdf .

- 69.Khoshnazar TA, Rassouli M, Akbari ME, Lotfi-Kashani F, Momenzadeh S, Haghighat S, et al. Structural challenges of providing palliative care for patients with breast cancer. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:459–66. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.191828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ansari M, Rassouli M, Akbari ME, Abbaszadeh A, Akbarisari A. Palliative care policy analysis in Iran: A conceptual model. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:51–7. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_142_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking Palliative Care Across the World. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit; 2015. Economist Intelligence Unit. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cancer Research Center. Development of a Comprehensive National Program for Palliative and Supportive Cancer Care Project. 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 01]. Available from: http://www.crc.tums.ac.ir/Default.aspx? tabid¼519 .

- 73.Memaryan N, Jolfaei AG, Ghaempanah Z, Shirvani A, Vand HD, Ghahari S, et al. Spiritual care for cancer patients in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:4289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services- Nursing Administration. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.amuzesh.muq.ac.ir/uploads/pain.pdf .

- 75.Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Discipline. 2010. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 22]. Available from: http://www.aac-hospital.com/files/khoon.pdf .

- 76.Pakseresht M, Baraz S, Rasouli M, Reje N, Rostami S. A comparative study of the situation of bereavement care for children with cancer in Iran with selected countries. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6:7253–63. [Google Scholar]