Abstract

We analyzed surveillance data for 2 sentinel hospitals to estimate the influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection hospitalization rate in Beijing, China. The rate was 39 and 37 per 100,000 persons during the 2014–15 and 2015–16 influenza seasons, respectively. Rates were highest for children <5 years of age.

Keywords: Influenza, severe acute respiratory infection, hospitalization, Beijing, China, viruses, SARI, respiratory infections

Influenza virus circulates worldwide, causing substantial rates of illness and death (1). In recent years, better estimates of influenza have been possible in low- and middle-income countries because of the development of surveillance systems (2,3).

Beijing is located in northern China in a temperate climate zone. Previous studies used surveillance to estimate the incidence of seasonal influenza infections in Beijing (4). However, hospitalizations associated with influenza have not been evaluated. We aimed to estimate the influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) hospitalization using the methods recommended by the World Health Organization (5).

The Study

We introduced screening of inpatients for SARI at 2 sentinel hospitals in Beijing during October 2014–September 2016. Throat swabs were collected from all SARI patients with their verbal consent. To explore the characteristics of severe influenza infections, we investigated the demographic characteristics and clinical courses of SARI patients (Technical Appendix).

We estimated the rate of influenza-associated SARI hospitalizations using WHO-recommended methods (5). First, we defined the catchment area of the 2 hospitals. We acquired home address (village or town) of all inpatients hospitalized in 2015 from the hospital discharge registry. Villages and towns from which most (>80%) SARI patients came were defined as the catchment area. We restricted the number of SARI and hospitalized patients to patients residing in the catchment area. Second, we estimated the number of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases among SARI patients residing in the catchment area, adjusting pro rata for the proportion of SARI patients from whom specimens were obtained and tested by age group. Third, we estimated the catchment population size by 5 age groups (<5 years, 5–14 years, 15–24 years, 25–59 years, and >60 years). Catchment populations were obtained from local population statistics (6,7). Next, we obtained the age group–specific annual number of patients with physician-diagnosed pneumonia served by each of the hospitals in the catchment area by examining hospital discharge registers. We adjusted catchment population size pro rata for the proportion of pneumonia patients served by the sentinel site. The rate of influenza-associated SARI hospitalization was estimated as follows: ([number of laboratory-confirmed influenza SARI patients in catchment area ÷ proportion swabbed] ÷ [population size of catchment area × proportion of pneumonia patients served by the sentinel site]) × 100,000.

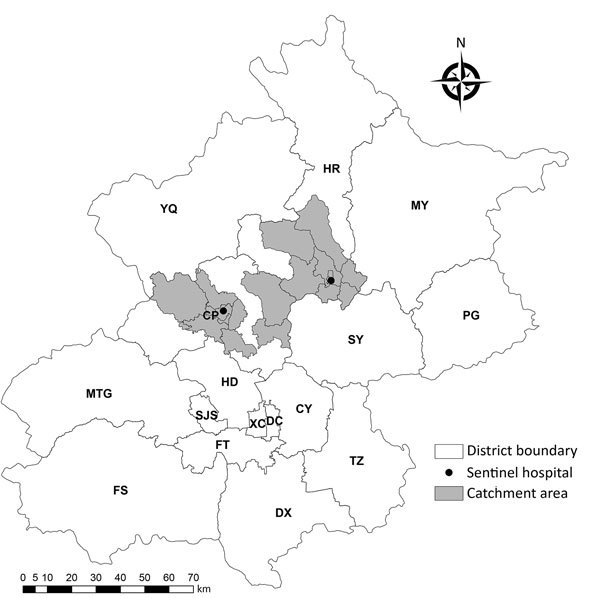

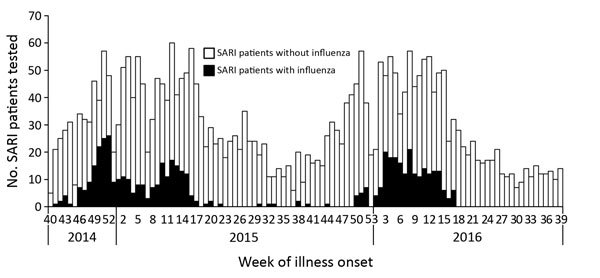

During the study period, 14,523 persons were hospitalized in the 2 sentinel hospitals, including 4,097 SARI patients. Eight towns were identified as catchment areas of the 2 hospitals (Figure 1,2). Of the 4,097 SARI patients, 3,899 (95.2%) resided in catchment areas and were enrolled. Swabs were collected from 3,130 (80.3%) SARI patients. Of these, 520 tested positive for influenza, resulting in a laboratory-confirmed influenza-positive proportion of 16.6%. Adjusting pro rata, the number of laboratory-confirmed influenza infections was 648 of 3,899 total SARI patients. The 2 hospitals served 93.2% of pneumonia patients in their catchment areas. Adjusting pro rata for this proportion provides a total catchment population of 842,895. Overall, the influenza-confirmed SARI hospitalization rate was 39 (95% CI 35–44) per 100,000 population during the 2014–15 influenza season and 37 (95% CI 33–41) per 100,000 population during the 2015–16 influenza season. The influenza A–confirmed SARI hospitalization rate was 24 (95% CI 21–28) per 100,000 population during the 2014–15 influenza season and 21 (95% CI 18–24) per 100,000 population during the 2015–16 influenza season; the influenza B–confirmed SARI hospitalization rate was 15 (95% CI 13–18) per 100,000 population during the 2014–15 influenza season and 16 (95% CI 14–19) per 100,000 population during the 2015–16 influenza season. In both seasons, the rate of influenza-associated SARI was highest for children <5 years of age: 335 (95% CI 277–401) hospitalizations per 100,000 population in the 2014–15 season and 529 (95% CI 456–611) hospitalizations per 100,000 population in the 2015–16 season. The rate was lowest in the 25–59-year age group: 2 (95% CI 1–6) hospitalizations per 100,000 population in the 2014–15 season and <1 hospitalization per 100,000 population in the 2015–16 season (Tables 1, 2; Technical Appendix).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of sentinel hospitals and catchment areas for surveillance of severe acute respiratory infection, Beijing, China, 2014–2016. CP, Chang Ping; CY, Chao Yang; DC, Dong Cheng; DX, Da Xing; FS, Fang Shan; FT, Feng Tai; HD, Hai Dian; HR, Huai Rou; MTG, Men Tou Gong; MY, Mi Yun; PG, Ping Gu; SJS, Shi Jing Shan; SY, Shun Yi; TZ, Tong Zhou; XC, Xi Cheng; YQ, Yan Qing.

Figure 2.

Number of total (N = 3130) and influenza-confirmed (n = 520) SARI patients from 2 sentinel hospitals combined, Beijing, China, week 40, 2014–week 39, 2016. SARI, sudden acute respiratory infection.

Table 1. Rates of influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection hospitalizations, Beijing, China.

| Age group, y |

Cases/100,000 population (95% CI). | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–15 influenza season |

|

2015–16 influenza season |

|||||

| Influenza A |

Influenza B |

All influenza |

Influenza A |

Influenza B |

All influenza |

||

| <5 | 223 (176–278) | 109 (77–149) | 335 (277–401) | 286 (233–348) | 243 (194–301) | 529 (456–611) | |

| 5–14 | 58 (41–80) | 61 (43–84) | 119 (94–150) | 26 (15–42) | 72 (53–97) | 98 (75–126) | |

| 15–24 | 2 (1–5) | 0 (0–3) | 2 (1–6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 25–59 | 5 (3–8) | 4 (3–7) | 10 (7–13) | 3 (2–6) | 1 (0–3) | 4 (3–7) | |

|

>60 |

69 (52–88) |

38 (26–53) |

105 (85–129) |

|

56 (41–74) |

10 (5–20) |

66 (50–86) |

| Overall | 24 (21–28) | 15 (13–18) | 39 (35–44) | 21 (18–24) | 16 (14–19) | 37 (33–41) | |

Table 2. Outcomes of SARI patients with and without laboratory-confirmed influenza. Beijing, China, week 40, 2014–week 39, 2016*.

| Characteristic | All SARI patients, n = 2,212 | SARI patients without confirmed influenza, n = 1,759 | SARI patients with confirmed influenza, n = 453 | p value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| M | 1,298 (58.7) | 1,030 (58.6) | 268 (59.2) | 0.816 |

| F |

914 (41.3) |

729 (41.4) |

185 (40.8) |

|

| Age group, y | ||||

| 0–4 | 973 (44.0) | 778 (44.2) | 195 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| 5–14 | 368 (16.6) | 260 (14.8) | 108 (23.8) | |

| 15–24 | 40 (1.8) | 35 (2.0) | 5 (1.1) | |

| 25–59 | 284 (12.8) | 235 (13.4) | 49 (10.8) | |

|

>60 |

547 (24.7) |

451 (25.6) |

96 (21.2) |

|

| Underlying medical condition | ||||

| >1‡ | 548 (24.8) | 450 (25.6) | 98 (21.6) | 0.083 |

| Pulmonary diseases§ | 224 (10.1) | 175 (10.0) | 49 (10.8) | 0.585 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 380 (17.2) | 321 (18.3) | 59 (13.0) | 0.009 |

| Metabolic diseases¶ | 71 (3.2) | 61 (3.5) | 10 (2.2) | 0.175 |

| Renal dysfunction | 22 (1.0) | 19 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) | 0.424 |

| Hepatic dysfunction | 10 (0.5) | 10 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.108 |

| Tumor | 31 (1.4) | 27 (1.5) | 4 (0.9) | 0.292 |

| Immune system diseases |

1 (0.1) |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0.0) |

0.612 |

| Received influenza vaccine within 1 y |

121 (5.5) |

90 (5.1) |

31 (6.8) |

0.15 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Antiviral drugs | 30 (1.4) | 14 (0.8) | 16 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Antibacterial drugs | 2,171 (98.2) | 1,722 (97.9) | 449 (99.1) | 0.086 |

| Corticosteroids | 214 (9.7) | 154 (8.8) | 60 (13.3) | 0.004 |

| Oxygen therapy | 589 (26.6) | 492 (28.0) | 97 (21.4) | 0.005 |

| Mechanical ventilation |

12 (0.5) |

8 (0.5) |

4 (0.9) |

0.428 |

| Complication | 510 (23.1) | 415 (23.6) | 95 (21.0) | 0.237 |

| Pneumonia |

389 (17.6) |

321 (18.3) |

68 (15.0) |

0.106 |

| Median length of hospital stay, d (IQR) |

8.8 (8.6–9.0) |

9.0 (8.7–9.3) |

8.0 (7.5–8.4) |

<0.001 |

| Admission to ICU |

28 (1.3) |

20 (1.1) |

8 (1.8) |

0.286 |

| Died | 9 (0.4) | 8 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0.485 |

*Values are no. (%) unless otherwise indicated. The weeks range from 2014 Sep 29 through 2016 Oct 2. ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; SARI, severe acute respiratory infection. †Calculated by χ2 test. ‡Defined as any inpatient stays with admission diagnosis in any of the following diseases, symptoms, or signs: pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic metabolic disease, renal dysfunction, hepatic diseases, or tumor. §Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis. ¶Diabetes, dyslipidemia.

Conclusions

In Beijing, influenza accounted for 16.6% of SARI in the 2 years studied; the hospitalization rate for all ages was 38–39 per 100,000 persons. This finding was much lower than that reported for Jingzhou, a city in central China, in which estimates ranged from 115 to 142 per 100,000 population in the 2010–12 influenza season (8). Although a similar method was used in these 2 studies, they had several differences. First, they estimated the hospitalization rate among different influenza seasons with different influenza activity and circulating strains. Second, the influenza circulation patterns differed (9); Beijing had 1 winter peak, whereas Jingzhou had an additional peak in summer. Moreover, the SARI definition used differed between the studies, with a lower fever threshold of >37.3°C in their study. As in other studies of age-specific influenza-associated SARI or hospitalization from other regions (3,10,11), we observed the most severe influenza disease in young children (<5 years). This finding underscores a need to consider influenza vaccination programs directed toward young children.

Although influenza B is often considered less severe than influenza A (12), 40.7% of influenza-confirmed SARI patients were influenza B–positive in this study, suggesting influenza B makes up an important component of overall influenza severity. Among the outpatient influenza infections in Beijing, 42.4% were influenza B during our study period, similar to the proportion in SARI patients (41.5%). These results suggest that influenza B is equally as responsible for mild and severe respiratory infections as influenza A.

Our study has some limitations. First, the results have limited generalizability because estimation was based on only 2 hospitals. However, 5 of the other sentinel hospitals are in the business district and serve populations of numerous districts and non-Beijing residents, making the catchment population difficult to estimate. We excluded the remaining 3 suburban sentinel hospitals because they did not have pediatric wards enrolled in SARI surveillance or the quality of their surveillance database was uncertain. Second, 19.7% of SARI patients in our study were not swabbed. We assumed the proportion of influenza-positive among them was the same as among swabbed SARI patients. However, according to clinician descriptions, most of these patients were children <5 years of age. Because the proportion of influenza-positive patients is higher among young children, we might have underestimated overall influenza-associated SARI. Third, because older adults often have complicated illness and not typical SARI symptoms, SARI might be underestimated among the older adult population. Fourth, surveillance covers only respiratory disease–related wards, but SARI patients might be hospitalized in other wards because of influenza complications (13,14), which might have led to underestimation of influenza. Finally, patients with influenza complications requiring admission might have had a relatively long delay from symptom onset to hospitalization, leading to possible false-negative laboratory results, thereby underestimating influenza.

Overall, most SARI patients in this study had influenza A, but the percentage with influenza B was also substantial. The findings of this study expanded knowledge about the impact of severe influenza and challenge the view that influenza B is a mild infection. These findings can be used to inform local policies on influenza prevention and control.

Additional methods for hospitalizations for influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection, Beijing, China, 2014–2016.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jérôme Ryan Lock-Wah-Hoon’s help in polishing our language.

This study was financially supported by Capital’s Fund for Health Improvement and Research (2018-1-1012), Beijing Science and Technology Planning Project of Beijing Science and Technology Commission (D141100003114002), Beijing Health System High Level Health Technology Talent Cultivation Plan (2013-3-098), Beijing Young Top-notch Talent Project (2014000021223ZK36). The DrPH scholarship for Y.Z. was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence in Epidemic Response, APP1107393.

Biography

Ms. Zhang, a PhD candidate in epidemiology in the University of New South Wales, works in the Beijing Municipal Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Her research interests focus on influenza vaccine effectiveness assessment, influenza burden estimation, and risk assessment of influenza and other respiratory infectious diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Zhang Y, Muscatello DJ, Wang Q, Yang P, Pan Y, Huo D, et al. Hospitalizations for influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection, Beijing, China, 2014–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Nov [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2411.171410

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO global epidemiological surveillance standards for influenza. Jan 2014. [cited 2017 Aug 12]. http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/WHO_Epidemiological_Influenza_Surveillance_Standards_2014.pdf?ua=1

- 2.Emukule GO, Khagayi S, McMorrow ML, Ochola R, Otieno N, Widdowson MA, et al. The burden of influenza and RSV among inpatients and outpatients in rural western Kenya, 2009-2012. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105543. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nukiwa N, Burmaa A, Kamigaki T, Darmaa B, Od J, Od I, et al. Evaluating influenza disease burden during the 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 influenza seasons in Mongolia. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2011;2:16–22. 10.5365/wpsar.2010.1.1.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Wu S, Yang P, Li H, Chu Y, Tang Y, et al. Using a community based survey of healthcare seeking behavior to estimate the actual magnitude of influenza among adults in Beijing during 2013-2014 season. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:120. 10.1186/s12879-017-2217-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. A manual for estimating disease burden associated with seasonal influenza [cited 2017 Aug 12]. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/178801

- 6.Huairou Bureau of Statistics. Statistical yearbook of Huairou (2015) [cited 2018 May 31]. https://wenku.baidu.com/view/8deb29e4ed630b1c59eeb5cc.html

- 7.Changping Bureau of Statistics. Statistical yearbook of Changping (2016) [cited 2018 May 31]. http://www.bjchp.gov.cn/tjj/tabid/621/InfoID/397815/frtid/5909/Default.aspx

- 8.Yu H, Huang J, Huai Y, Guan X, Klena J, Liu S, et al. The substantial hospitalization burden of influenza in central China: surveillance for severe, acute respiratory infection, and influenza viruses, 2010-2012. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2014;8:53–65. 10.1111/irv.12205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Alonso WJ, Feng L, Tan Y, Shu Y, Yang W, et al. Characterization of regional influenza seasonality patterns in China and implications for vaccination strategies: spatio-temporal modeling of surveillance data. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001552. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheu SM, Tsai CF, Yang HY, Pai HW, Chen SC. Comparison of age-specific hospitalization during pandemic and seasonal influenza periods from 2009 to 2012 in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:88. 10.1186/s12879-016-1438-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller JA, Summers A, Katz MA, Lindblade KA, Njuguna H, Arvelo W, et al. Estimation of the national disease burden of influenza-associated severe acute respiratory illness in Kenya and Guatemala: a novel methodology. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56882. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YH, Kim HS, Cho SH, Seo SH. Influenza B virus causes milder pathogenesis and weaker inflammatory responses in ferrets than influenza A virus. Viral Immunol. 2009;22:423–30. 10.1089/vim.2009.0045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ang LW, Yap J, Lee V, Chng WQ, Jaufeerally FR, Lam CSP, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases in the tropics. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:202–9. 10.1093/aje/kwx001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sellers SA, Hagan RS, Hayden FG, Fischer WA II. The hidden burden of influenza: A review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2017;11:372–93. 10.1111/irv.12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional methods for hospitalizations for influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection, Beijing, China, 2014–2016.