Abstract

Bacteriophages, bacteria-infecting viruses, have been recently reconsidered as a biological control tool for preventing bacterial pathogens. Erwinia amylovora and E. pyrifoliae cause fire blight and black shoot blight disease in apple and pear, respectively. In this study, the bacteriophage phiEaP-8 was isolated from apple orchard soil and could efficiently and specifically kill both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae. This bacteriophage belongs to the Podoviridae family. Whole genome analysis revealed that phiEaP-8 carries a 75,929 bp genomic DNA with 78 coding sequences and 5 tRNA genes. Genome comparison showed that phiEaP-8 has only 85% identity to known bacteriophages at the DNA level. PhiEaP-8 retained lytic activity up to 50°C, within a pH range from 5 to 10, and under 365 nm UV light. Based on these characteristics, the bacteriophage phiEaP-8 is novel and carries potential to control both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae in apple and pear.

Keywords: Bacteriophage, black shoot blight, Erwinia amylovora, Erwinia pyrifoliae, fire blight

Erwinia amylovora and E. pyrifoliae are Gram-negative bacterial pathogens that cause the devastating diseases, fire blight and bacterial black shoot blight, in apple and pear, respectively. Since E. amylovora was first discovered in 1780 in the United States, it has been reported globally in Europe, North America, the Middle East and central Asia, and New Zealand (Van der Zwet et al., 2012). In 2015, this disease was reported in apple and pear orchards in South Korea (Myung et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016). In the case of E. pyrifoliae, it was first reported in pear orchards in South Korea in 1995 (Kim et al., 1999). These two pathogens are quarantine pathogens in South Korea and have caused severe economic loss due to extensive host eradication and difficulty of fruit export (Park et al., 2017).

So far, antibiotics and copper compounds have been mostly used for the control of fire blight and bacterial black shoot blight in apple and pear. However, the appearance of bacteria resistant to these chemicals have limited their use in the field (Manulis et al., 1998). As an alternative, lytic bacteriophages have been reconsidered as a tool for biological control (Loc-Carrillo and Abedon, 2011). Bacteriophages infect very specific target bacteria, and their host ranges are very narrow unlike antibiotics and copper compounds. They have two different life cycles: the lytic and the lysogenic cycles. During the lytic cycle, a bacteriophage actively infects host bacteria, multiplies inside the host, and kills the host to release progeny (Orlova, 2012). Due to this feature, lytic bacteriophages have been used for phage therapy to control many bacterial pathogens causing disease in animals and plants (Buttimer et al., 2017; Doffkay et al., 2015).

Since the 1960’s, many bacteriophages effective against E. amylovora have been reported, and their genomic and physiological features have been determined (Born et al., 2011; Esplin et al., 2017; Gill et al., 2003; Meczker et al., 2014; Müller et al., 2011; Yagubi et al., 2014). Based on the morphology of these bacteriophages, they belong to either the Myoviridae or Podoviridae family. Some bacteriophages with a broad host range have been applied for phage therapy to control E. amylovora (Meczker et al., 2014) and some of them have been commercialized (Buttimer et al., 2017). However, no bacteriophages effective against E. pyrifoliae or both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae have yet been reported.

In this study, to isolate bacteriophages with effective host specificity to both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae, 18 soil samples from apple and pear orchards at Jecheon, Chungju, and Yongin, South Korea were collected. After mixing soil with SM (sodium chloride-magnesium sulfate) buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgSO4] for 30 min, the mixed samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm, 4°C for 10 min and filtered with a 0.22 μm pore size filter (Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany). Then, bacteriophages were enriched through overnight incubation with 5ml of the supernatant, 10 ml of LB, and 500 μl of bacterial suspension (109 cfu/ml) of E. amylovora strain Ea-K1 isolated in South Korea at 26°C in a shaking incubator. The incubated samples were treated with chloroform (1% of the final volume) for 30 min, centrifuged at 3,000 g, 4°C for 15 min, and filtered with a 0.22 μm pore size filter. The presence of bacteriophages in the supernatant was confirmed with four E. amylovora strains and two E. pyrifoliae strains using a dotting assay (Kropinski et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2016). Then, in order to isolate individual bacteriophages, the overlay assay (Yu et al., 2016) was performed, and plaques with different sizes and shapes were picked separately. A total of 21 individual bacteriophages were picked based on their plaque sizes and shapes (Fig. 1). To determine whether isolated bacteriophages were separate isolates, the genomic DNAs from the 21 isolated bacteriophages were extracted using a phage DNA isolation kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON, Canada) and digested with restriction enzymes, EcoRI, BamHI or both. According to DNA patterns, isolated bacteriophages were categorized into three groups. The bacteriophage phiEaP-8 isolated from apple orchard soil in Yongin, South Korea, where no fire blight or bacterial black shoot blight has been reported, represents one of the three groups and this bacteriophage was used for further characterization.

Fig. 1.

Plaques from the overlay assay after extracting from soil (top left) and the dotting assay (bottom) with purified serially diluted phiEaP-8 against E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae. Morphology of the bacteriophage phiEaP-8 (top right) was determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Photos were taken at the KBSI (Korea Basic Science Institute).

To determine the shape of bacteriophage phiEaP-8, it was propagated by incubating with the Ea-K1 strain (OD600 = 0.5–1.0), as described previously (Kim and Ryu, 2011), and was then purified using CsCl gradient ultracentrifugation (Lim et al., 2013). After ultracentrifugation at 25,000 rpm, 4°C for 2 h, bacteriophages were collected and purified through dialysis twice for 1 h in SM buffer. The purified bacteriophage phiEaP-8 was observed by transmission electron microscopy at 120 kV after negative straining with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (pH 4.0) on carbon-coated copper grids (Ackermann and Heldal, 2010; Brum and Steward, 2010). The bacteriophage phiEaP-8 belonged to the Podoviridae family based on its morphology (Fig. 1). The total length and head size are 95 nm and 75 nm, respectively.

Next, the host range of the bacteriophage phiEaP-8 was determined by an overlay assay with twenty E. amylovora and seven E. pyrifoliae strains isolated in Korea as well as other related bacteria such as Pectobacterium carotovorum, Dickeya zeae and three Pantoea strains. The bacteriophage phiEaP-8 could efficiently kill all tested strains of both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae, but it was not effective against other related bacteria (Table 1), indicating that this bacteriophage is very likely specific to both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae.

Table 1.

Host range of the bacteriophage phiEaP-8

| No. | Bacterial species | Strain | Lytic activity* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea73 | + |

| 2 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea74 | + |

| 3 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea75 | + |

| 4 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea76 | + |

| 5 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea77 | + |

| 6 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea78 | + |

| 7 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea-K1 | + |

| 8 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea80 | + |

| 9 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea2016-1 | + |

| 10 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea2016-2 | + |

| 11 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea2016-3 | + |

| 12 | Erwinia amylovora | Ea2016-4 | + |

| 13 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12316 (TS 3128) | + |

| 14 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12317 (TS3133) | + |

| 15 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12318 (TS 3240) | + |

| 16 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12319 (TS 3241) | + |

| 17 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12320 (TS 3315) | + |

| 18 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12321 (TS 3325) | + |

| 19 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12322 (TS 3371) | + |

| 20 | Erwinia amylovora | YKB 12323 (TS 3373) | + |

| 21 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | Ep81 | + |

| 22 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | EpK1/15 | + |

| 23 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | YKB 12324 (TS 2743) | + |

| 24 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | YKB 12325 (TS 2744) | + |

| 25 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | YKB 12326 (TS 3239) | + |

| 26 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | YKB 12327 (TS 3340) | + |

| 27 | Erwinia pyrifoliae | YKB 12328 (TS 3342) | + |

| 28 | Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum | Pcc21 | − |

| 29 | Dickeya Zeae | − | |

| 30 | Pantoea dispersa | − | |

| 31 | Pantoea agglomerans | − | |

| 32 | Pantoea stewartii | − |

+, positive; −, negative

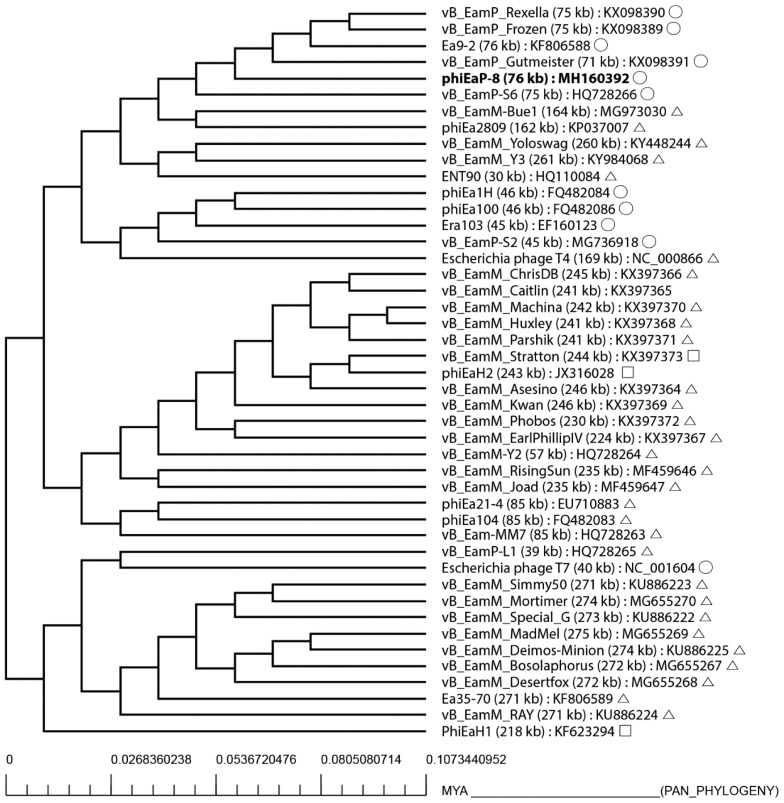

To examine if the bacteriophage phiEaP-8 is homologous to known bacteriophages, whole genome sequencing was performed using the PacBio RS II platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Total genomic DNA of phiEaP-8 was isolated using a phage DNA isolation kit (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON, Canada), and 10 ug was used to generate a 10 kb SMRTbellTM template library. After sequencing, de novo assembly was performed using CANU v1.4 (Koren et al., 2017) and a single contig was generated. The bacteriophage phiEaP-8 carries a 75,929 bp genomic DNA (GenBank accession number, MH160392), and its G+C content is 46.8%. In order to compare the phiEaP-8 genome with other sequenced bacteriophages, which can infect E. amylovora, 42 sequenced genomes were obtained from GenBank database, and their genome were compared with BPGA (Bacterial Pan Genome Analysis) pipeline (Chaudhari et al., 2016) and USEARCH (Edgar, 2010). Specifically, 10 of them are Podoviridae, 29 of them are Myoviridae, and 3 bacteriophages are Siphoviridae. Based on a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1), phiEaP-8 was closely related to five bacteriophages belonging to Podoviridae, which are vB_EamP_Rexella (GenBank accession number, KX098390), vB_EamP_Frozen (GenBank accession number, KX098389), Ea9-2 (GenBank accession number, KF806588), vB_EamP_Gutmeister (GenBank accession number, KX098391), and vB_EamP-S6 (GenBank accession number, HQ728266). At the DNA level, phiEaP-8 only has about 85% identity to these closely related bacteriophages.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree with phiEaP-8 and other 42 Erwinia amylovora bacteriophages. The genome sequences were obtained from GenBank database, and their names, sizes, and accession numbers were stated in the figure. The tree was generated with BPGA pipeline and USEARCH tool. Escherichia phages, T4 and T7 bacteriophages, were used as an outgroup. Circle, Podoviridae; triangle, Myoviridae; square, Siphoviridae.

Gene annotation to find coding sequences (CDS), tRNA, and rRNA genes was performed using Prokka (v1.12b). Gene annotation showed that the genome contains 78 CDSs and 5 tRNA genes, but no rRNA genes (Supplementary Table 1). The bacteriophage phiEaP-8 genome carries genes encoding putative holin and Rz/Rz1 spanin proteins, indicating that it is a lytic bacteriophage. Interestingly, this bacteriophage carries a gene homologous to amsF responsible for amylovoran biosynthesis in E. amylovora and also a gene encoding serine protease highly homologous to one in Enterobacteriaceae like Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. These results indicate that this bacteriophage might have obtained these genes from host bacteria during infection and genome multiplication.

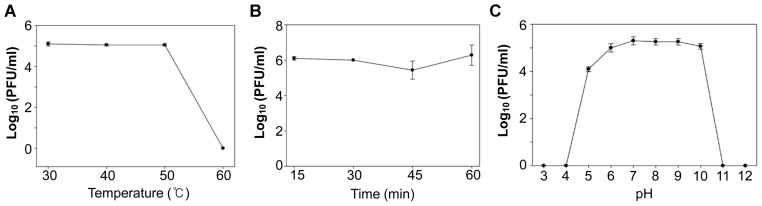

To determine if phiEaP-8 can be used for phage therapy against both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae, its lytic activity under diverse environmental conditions was examined. For this, 105 PFU/ml of bacteriophages were treated for 1 h at 30, 40, 50, and 60°C, at pH range 3 to 12, or under 365 nm UV light, and its lytic activity was measured by the dotting assay. This bacteriophage retained lytic activity stable against E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae up to 50°C, within a pH range from 5 to 10, and under 365 nm UV light (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Stability of the bacteriophage phiEaP-8 under diverse environmental conditions. (A) Temperature. (B) 365 nm UV light. (C) pH. Bacteriophages were counted as PFU/ml by a dotting assay. All tests were repeated at least three times. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Bacteriophages are typically isolated from soil, water, and plants surrounding infected trees (Doffkay et al., 2015; Müller et al., 2011). Interestingly, the apple orchard in Yongin, South Korea where phiEaP-8 was isolated has never been infected with either E. amylovora or E. pyrifoliae. In a previous paper (Lagonenko et al., 2015), phiEa2809 was isolated from the leaves of an apple tree without fire blight symptoms in an apple orchard where fire blight was never detected. The genus Erwinia is classified to the Enterobacteriaceae family, which includes both pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria in genera such as Erwinia, Enterobacter, Pantoea, Pectobacterium, and Brenneria (Kado, 2006). Presence of bacteriophages in an apple orchard, in which fire blight or bacterial black shoot blight have never been detected, might be explained by the thought that bacteriophages could exist owing to the presence of some of these bacteria.

Born et al. (2011) reported eight bacteriophages effective against E. amylovora. Interestingly, some of them were effective against other related bacteria such as Erwinia billingiae, Pantoea agglomerans, and Pantoea ananatis, indicating the presence of wide host-range bacteriophages. The bacteriophage phiEaP-8 looks specific to both E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae, which indicates that this is a somewhat narrow host-range bacteriophage. However, this bacteriophage could be very useful because both pathogenic bacteria can co-exist in apple and pear orchards in Korea.

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Young-Gi Lee for providing YKB strains of Erwinia amylovora and Erwinia pyrifoliae and the Korea Basic Science Institute for TEM analysis. This work was carried out with the support of the “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project No: PJ0117582018)” of the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea and Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry (IPET) through Agri-Bio industry Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (No. 317012-4).

References

- Ackermann HW, Heldal M. Basic electron microscopy of aquatic viruses. In: Wilhelm SW, Weinbauer MG, Suttle CA, editors. Manual of aquatic viral ecology. American Society of Limnology and Oceanography; 2010. pp. 182–192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Born Y, Fieseler L, Marazzi J, Lurz R, Duffy B, Loessner MJ. Novel virulent and broad-host-range Erwinia amylovora bacteriophages reveal a high degree of mosaicism and a relationship to Enterobacteriaceae phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5945–5954. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03022-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brum JR, Steward GF. Morphological characterization of viruses in the stratified water column of alkaline, hypersaline Mono Lake. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:636–643. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9688-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttimer C, McAuliffe O, Ross RP, Hill C, O’Mahony J, Coffey A. Bacteriophages and bacterial plant diseases. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:34. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari NM, Gupta VK, Dutta C. BPGA-an ultra-fast pan-genome analysis pipeline. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24373. doi: 10.1038/srep24373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doffkay Z, Dömötör D, Kovács T, Rákhely G. Bacteriophage therapy against plant, animal and human pathogens. Acta Biol Szeged. 2015;59:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esplin IN, Berg JA, Sharma R, Allen RC, Arens DK, Ashcroft CR, Bairett SR, Beatty NJ, Bickmore M, Bloomfield TJ, Brady TS, Bybee RN, Carter JL, Choi MC, Duncan S, Fajardo CP, Foy BB, Fuhriman DA, Gibby PD, Grossarth SE, Harbaugh K, Harris N, Hilton JA, Hurst E, Hyde JR, Ingersoll K, Jacobson CM, James BD, Jarvis TM, Jaen-Anieves D, Jensen GL, Knabe BK, Kruger JL, Merrill BD, Pape JA, Anderson AMP, Payne DE, Peck MD, Pollock SV, Putnam MJ, Ransom EK, Ririe DB, Robinson DM, Rogers SL, Russell KA, Schoenhals JE, Shurtleff CA, Simister AR, Smith HG, Stephenson MB, Staley LA, Stettler JM, Stratton ML, Tateoka OB, Tatlow PJ, Taylor AS, Thompson SE, Townsend MH, Thurgood TL, Usher BK, Whitley KV, Ward AT, Ward MEH, Webb CJ, Wienclaw TM, Williamson TL, Wells MJ, Wright CK, Breakwell DP, Hope S, Grose JH. Genome sequences of 19 novel Erwinia amylovora bacteriophages. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e00931–00917. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00931-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill JJ, Svircev AM, Smith R, Castle AJ. Bacteriophages of Erwinia amylovora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2133–2138. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2133-2138.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado CI. Erwinia and related genera. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E, editors. The Prokaryotes. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2006. pp. 443–450. The prokaryotes. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Ryu S. Characterization of a T5-like coliphage, SPC35, and differential development of resistance to SPC35 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2042–2050. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02504-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Gardan L, Rhim SL, Geider K. Erwinia pyrifoliae sp. nov., a novel pathogen that affects Asian pear trees (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:899–906. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropinski AM, Mazzocco A, Waddell TE, Lingohr E, Johnson R. Enumeration of bacteriophages by double agar overlay plaque assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;501:69–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-164-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagonenko AL, Sadovskaya O, Valentovich LN, Evtushenkov AN. Characterization of a new ViI-like Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage phiEa2809. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015;362:fnv031. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JA, Jee SN, Lee DH, Roh EJ, Jung KS, Oh CS, Heu SG. Biocontrol of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum using bacteriophage PP1. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;23:1147–1153. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1304.04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loc-Carrillo C, Abedon ST. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage. 2011;1:111–114. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.2.14590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manulis S, Zutra D, Kleitman F, Dror O, David I, Zilberstaine M, Shabi E. Distribution of streptomycin-resistant strains of Erwinia amylovora in Israel and occurrence of blossom blight in the autumn. Phytoparasitica. 1998;26:223–230. doi: 10.1007/BF02981437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meczker K, Dömötör D, Vass J, Rákhely G, Schneider G, Kovács T. The genome of the Erwinia amylovora phage PhiEaH1 reveals greater diversity and broadens the applicability of phages for the treatment of fire blight. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014;350:25–27. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller I, Lurz R, Kube M, Quedenau C, Jelkmann W, Geider K. Molecular and physiological properties of bacteriophages from North America and Germany affecting the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:735–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung IS, Lee JY, Yun MJ, Lee YH, Lee YK, Park DH, Oh CS. Fire blight of apple, caused by Erwinia amylovora, a new disease in Korea. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1774–1774. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-16-0024-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orlova E. Bacteriophages and their structural organisation. In: Kurtboke I, editor. Bacteriophage. InTech; London, UK: 2012. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Park DH, Yu JG, Oh EJ, Han KS, Yea MC, Lee SJ, Myung IS, Shim HS, Oh CS. First report of fire blight disease on Asian pear caused by Erwinia amylovora in Korea. Plant Dis. 2016;100:1946–1946. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-15-1364-PDN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park DH, Lee YG, Kim JS, Cha JS, Oh CS. Current status of fire blight caused by Erwinia amylovora and action for its management in Korea. J Plant Pathol. 2017;99:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zwet T, Orolaza-Halbrendt N, Zeller W. Fire blight: history, biology, and management. Amer Phytopathological Society; Saint Paul, MN, USA: 2012. p. 421. [Google Scholar]

- Yagubi AI, Castle AJ, Kropinski AM, Banks TW, Svircev AM. Complete genome sequence of Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage vB_EamM_Ea35–70. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e00413–e00414. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00413-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JG, Lim JA, Song YR, Heu SG, Kim GH, Koh YJ, Oh CS. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae causing bacterial canker disease in kiwifruit. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26:385–393. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1509.09012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.