Abstract

Lara Fairall and colleagues reflect on the successes and challenges of a programme to strengthen primary healthcare in low and middle income countries

Forty years ago, when world leaders met in Alma Ata, the world was home to 4.3 billion people. The resultant declaration provided a bold vision where everyone had access to healthcare and affirmed the pivotal role of primary healthcare in achieving this. But the declaration was soon dismissed as an idealistic dream, and multilaterals, academia, and clinicians instead busied themselves with the low hanging fruits, in particular specific drivers of mortality, in what became known as selective primary healthcare.1 These efforts were not without successes: childhood mortality halved; conditions like polio and river blindness almost eliminated; hundreds of thousands of lives saved by the scale-up of antiretroviral treatment; and Ebola and other outbreaks contained. But such programmatic achievements have not yielded robust health systems.

When the World Health Organization, Unicef, and government health leaders meet in Astana on 25-26 October 2018, they will consider a world population that has swelled to 7.4 billion, of whom half have limited access to essential health services and 400 million no access to any health service.2 Governments have still to figure out how to deliver quality healthcare that is effective, safe, and person centred.3 Health systems, especially primary healthcare systems in low and middle income countries (LMICs), remain rudimentary or non-existent at worse, and fragile and fragmented at best, unable to meet current realities of inequality, global migration, and changing disease burdens.4 5 At the coalface are frontline providers, often portrayed as poorly qualified, unskilled, and even uncaring. In reality most are overworked, unsupported, poorly paid, and feel unrecognised, isolated, and traumatised by the demands made on them.

Global efforts to strengthen primary healthcare have generally not focused on the critical interface between provider and patient but rather on policy, financing, and infrastructure. In many countries providers are non-physician clinicians who lack the knowledge and skills to provide effective person centred care.

Over the past two decades the Knowledge Translation Unit at the University of Cape Town has worked with government, academic, and non-governmental organisation partners to develop and evaluate health systems innovations that empower frontline providers. This began with a local adaptation of WHO’s Practical Approach to Lung Health (PAL), which used an integrated approach to the diagnosis and management of respiratory diseases, including tuberculosis.6 The unit built on its experience of implementing PAL in rural South Africa, and, in response to requests of providers and their managers, progressively expanded its scope to include most problems that people present with at clinics in South Africa and evolved a programme that covers primary healthcare needs across the life course. Now called the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK), the programme has crossed borders and has been implemented in diverse settings in several LMICs.7 8 9 10 11

This experience is described in a collection of papers in BMJ Global Health (https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/Suppl_5). The collection is not intended to showcase best practice but rather is an attempt to describe this journey, both successes and challenges, during this time of reflection on the role of primary healthcare and the people who make it possible.

PACK programme

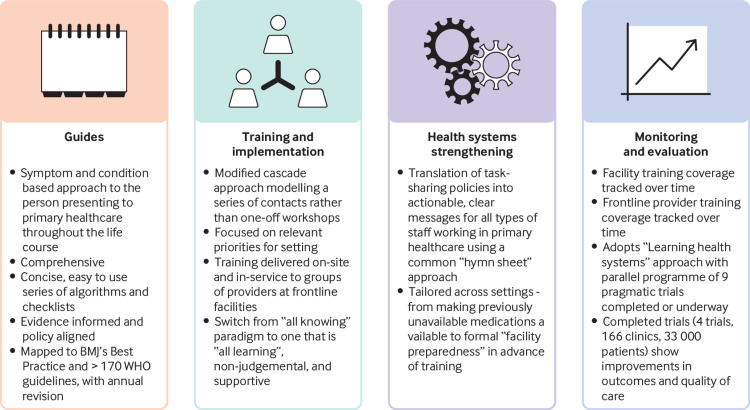

PACK is designed to support frontline providers who act as the first point of contact with health services (fig 1). To date it has focused on clinicians working in primary care facilities in LMICs. At the centre of the programme are concise clinical decision support tools (guides) comprising standardised and user friendly algorithms and checklists that provide a comprehensive and integrated approach to screening, diagnosing, and treating common symptoms and chronic conditions in adults,12 adolescents, and children.13 All medications are drawn from the 2017 WHO essential medicines list.14 Although most editions of the guides are printed, an interactive ebook version of the adult guide (2018 global edition) is now available free to providers (https://knowledgetranslation.co.za).

Fig 1.

Components of the PACK programme

But PACK is much more than a book. The accompanying training programme uses case-based, short training sessions delivered by existing health staff to support frontline providers and their teams.15 The training time commitments are modest, mindful of the need to support scalable implementation and not withdraw providers from clinical service for prolonged periods to attend offsite training.7 The culture of implementation and training is paramount. PACK draws on adult learning theory and practice, assuming that frontline providers bring with them much knowledge and experience. It models interprofessional respect and the shift from “all knowing” hierarchical knowledge systems to one that is “all learning,” non-judgmental, and supportive. Training focuses on health priorities, which differ across settings,15 and aims to equip health workers to use the full content of the guide.

The components for strengthening health systems are varied and setting dependent. In some, attention to resourcing of drugs and investigations by health facilities must precede training of health workers.10 One universal aspect is the translation of task sharing policies into actionable, clear, and consolidated messages to the range of health workers who staff facilities.

PACK uses a simple system, colour coding all medications every time they are listed, by indication and dose for different types of health worker, localised for the particular health system. This seemingly simple classification requires extensive engagement with health managers, policy makers, regulatory policies, and clinicians and is a key component of localising PACK to a particular setting.16 The aim is to shift responsibility for determining scope of practice from health workers under pressure navigating patients, guidelines, and new policies, to governance structures and regulatory frameworks by clarifying what governments think is appropriate to ask of their health workers under the current circumstances.

Areas where there is a lack of clarity or large unmet needs are presented in terms of clinical situations: “What should this type of health worker be able to offer the person in front of them at this time?” Regular revision assures policy makers that they can revisit their decisions. The outcome is a common “hymn sheet” used by all types of primary healthcare worker to understand their role in the healthcare system.

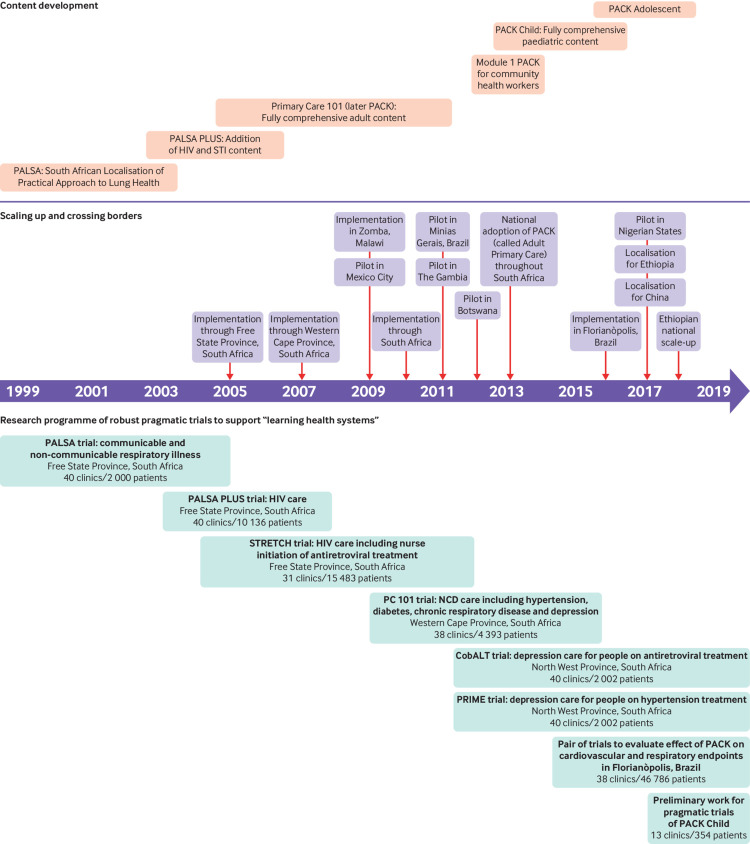

Routine monitoring and evaluation of the programme is less well developed and has focused on tracking training coverage both across and within facilities (fig 2). We have completed four large pragmatic implementation science trials, including 33 000 patients from 166 clinics. Qualitative evaluation has shown substantial positive effects on health worker confidence and teamwork.17 18 We have found consistent, reproducible improvements in quality of care across several indicators (prescribing, referral, case detection) mainly in the area of communicable diseases.19 20 21 22 Absolute effect sizes are in line with implementation science literature, and effects extend to health outcomes and economic benefits, including fewer and shorter hospital admissions.21 23 A further four trials involving almost 50 000 patients from 88 clinics are underway, with components evaluating mental health24 25 and non-communicable diseases,26 as well as preliminary work for a trial of PACK Child.27

Fig 2.

Development of PACK over the past 18 years

Less is known about the performance of PACK outside these trials, but the pragmatic orientation of these trials suggests that it should be no different in other situations. Numerous efforts are underway to establish routine monitoring and evaluation systems that can track training uptake in a health workforce that has high rates of turnover; to explore relations between training and simple indicators of care; and to assess fidelity to the principles of training.

PACK has been widely adopted in South Africa, where it forms part of the government’s ideal clinic realisation and maintenance programme across 3500 primary care facilities.28 It is also used in Botswana,8 Nigeria,10 and Brazil,9 and forms a central component of the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health’s health sector transformation plan.11 To date around 200 000 hard copies of 42 editions of the guide have been distributed and more than 30 000 health workers trained.

PACK is gaining widespread traction among health ministries seeking to strengthen their primary healthcare systems. It is currently being considered in China, Vietnam, Uganda, and Bangladesh. Since 2015 a further 28 countries across six continents have asked about localisation and implementation. Ministries report being attracted by the comprehensive and integrated approach, consolidating and unifying guidance across communicable and non-communicable diseases, age range, and the scalable, carefully designed programme for training multiprofessional teams together on-site instead of separately at centralised venues.

Language of “clinician”—a novel approach to strengthening health systems

During the late 2000s we started noting how introducing PACK at facilities often catalysed local, clinician-led efforts to improve healthcare delivery in their own facilities. For example, Botswana’s adaptation of PACK proposed 36 new additions to the local essential medications list for primary care, including making statins available for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease as well as for antiretroviral induced dyslipidaemias.8 Enthused clinicians engaged with government pharmaceutical services to ensure that their facilities had adequate supplies of drugs recommended in PACK, even compiling their own lists of medications by painstakingly identifying each one from the guide or sourcing drugs previously not provided to the clinic. Others identified patients with chronic conditions and reviewed their treatment plans to ensure that they reflected the evidence and policy aligned recommendations in the guide. Some teams worked together to review patients’ experience of care in their facilities, streamlining flow to avoid duplication of roles and conserve valuable consultation time.

Initially such feedback was heartening, but as this pattern started repeating across facilities and countries, it prompted reflection on what was happening. All these efforts seemed to be deeply rooted in the clinical content of the PACK programme rather than parallel quality improvement processes. Clinicians seem to have claimed “system agency” based on an intervention that resonated with their primary identity as providers concerned principally with the welfare of the person sitting in front of them.29 This warrants further exploration, recognising that delivering healthcare is not only about optimising efficiencies but is fundamentally a human endeavour at the heart of which lies the critical interaction between two people, one of whom is in the provider role and one in the patient role.

Reconciling comprehensive and selective approaches to primary healthcare

How best to structure primary healthcare is the subject of much debate. Should we continue with the basket of low cost, high impact interventions targeting high burden, measurable diseases? Or has the time come to strive for comprehensive integrated person centred care? The answer lies not with a pros and cons list of these polarised views, but with a more nuanced understanding of the factors that have contributed to and perpetuated the priorities approach and an honest appraisal of why an integrated approach is imperative but seemingly beyond reach.

Disease based approaches are embedded in health worker training curriculums worldwide.30 When graduates enter health systems they view health as a group of systems that work alongside each other. Identifying which of these is dysfunctional and targeting interventions is considered the basis of healthcare delivery. Health systems replicate this siloed approach in career paths and specialisation, in how ministries organise themselves, in research and donor funding, in reporting systems, among patient and community advocacy groups, and in the media. We all relate to a cause, whether it be AIDS, mental illness, or the leading causes of childhood deaths. Protagonists of person centred care emphasise that patients and communities should set the agenda of healthcare and point out that appropriate uptake and demand are unlikely to materialise without tackling what matters most to them.

The solution lies in crafting a workable compromise, whereby patients and communities experience satisfying contacts with frontline providers, building their trust and use of healthcare systems and the interventions they provide. People who feel heard and cared for when seeking care for common non-life-threatening illnesses are more likely to seek care from that service at critical moments when effective treatment can substantially influence their morbidity and mortality. This is especially relevant to hard-to-reach populations, including adolescents around the world, men in sub-Saharan Africa, and women in South East Asia. But the gains achieved by focused interventions cannot be ignored. Ultimately it would be myopic not to appreciate the fact that some, like antiretrovirals and vaccinations, are more effective than others and save many lives when implemented at scale.

An all learning approach is essential to balance the tension between comprehensiveness and focus. The Knowledge Translation Unit has insisted that local editions of PACK guides be comprehensive and not extract selected components to augment a disease based intervention. Prospective adopters of PACK often perceive this as extraneous work that will delay implementation. Delays can be ameliorated by streamlining the localisation process as far as possible and strengthening mentorship of in-country teams. Training, however, is always focused on disease priorities in each setting and uses a tailored curriculum drawn from a global bank of cases.

Providers appreciate the inclusion of common non-life-threatening conditions as this empowers them to manage a high proportion of their patients, often overlooked by disease focused initiatives. For example, although pneumonia and diarrhoea remain leading causes of childhood mortality, snotty noses and skin rashes continue to be common reasons for encounters with health services. The shift towards meeting the needs of people with chronic conditions offers an opportunity to build primary healthcare systems that can respond to both acute and chronic illnesses in a timely, cost effective way.

Work environments characterised by long patient queues, out-of-stock drugs, and inaccessible tests and referrals make provision of person centred care near impossible. Societal problems such as poverty, interpersonal violence, and marginalisation can overwhelm even the most straightforward of consultations. Containment of situations and connection to appropriate resources are essential skills for frontline providers. PACK aims to contribute by starting with clear guidance on how best to manage the clinical aspects of a consultation, recognising that clinicians who fear missing a potentially fatal diagnosis or are uncertain about how to start assessing a particular complaint are in no position to provide person centred care. We have developed clinical communication skills focused on mental health in our training programmes24 25 and are raising awareness of the understanding that person centred care includes care of clinicians too.

Building learning health systems

PACK is unusual in that it has been built on a series of nine large pragmatic trials (fig 2), which have facilitated rapid adoption of evidence into policy and practice in what has been promoted as “learning health systems.”31 In South Africa the trials have supported a move away from centralised training to a cascade system that is team based and on-site and has been adopted by other training providers and programmes. The trials have also underpinned and informed the adoption of nurse initiated and managed antiretroviral treatment, and contributed to policy decisions to adopt the South African version of PACK. The second and third trials helped establish a province-wide health information and monitoring system for HIV, which additionally highlighted the big effect of antiretroviral treatment and high mortality among patients waiting a prescription,32 motivating the decision to switch to nurse initiation.

But routine data collection outside of communicable diseases is near absent in many LMICs, and the four trials evaluating the effects on these conditions have required years of fieldwork with as many as 19 000 patient interviews. Disappointing results in a trial evaluating hypertension, diabetes, and depression care22 prompted intense reflection on the nature of the intervention. We had to justify a national decision to adopt PACK despite the results, which required engagement of policy makers in a discourse that considered context, the urgent need to tackle non-communicable disease, interpretation of pragmatic trials, and consideration of several secondary outcomes that indicated better care.33 We decided not to undertake such research in future without extensive mixed methods formative and summative evaluation, irrespective of funding restraints. Rigorous research in these contexts is difficult, but, because of its capacity to outlive annual budget cycles and political terms and to refine complex health systems interventions, it is needed to guide evidence informed strengthening of health systems.

Future of PACK: is global expansion possible?

The future of PACK depends on several factors: the need, the performance of PACK in meeting that need, alternative approaches, and sustainability. The demand we have had for PACK, even though it is not endorsed by official agencies, is testament to the need and the appeal of the approach. Although alternatives exist, the localisation, comprehensiveness, and training methods of PACK and its record of development have gained traction with both clinicians and policy makers.

Unquestionably, the greatest challenge should be the easiest to address: consolidating this international resource and continuing to develop regional and local hubs to maintain, develop, and support countries that are looking to PACK to strengthen provision of primary healthcare. The current structure of funding in LMICs does not permit this. Provision of health services in many of these countries depends on donors, who require that countries deliver return on investment in the short term, typically in annual cycles, and attempt to meet unrealistic targets or face big cuts or even funding withdrawal. Poor investment by LMICs in health research has resulted in research agendas that are set by high income country donors and remain almost exclusively disease based. Even groundbreaking initiatives such as the Global Alliance Against Chronic Disease organised three of its four funding rounds by disease.

In contrast the Knowledge Translation Unit’s efforts have been almost entirely supported by grant funding and the budget is paltry compared with the budgets of disease specific initiatives supported by global and national donors. The revised Alma Ata declaration commits international agencies, including WHO, Unicef, and other UN agencies, to investments towards realising universal health coverage through people centred primary healthcare systems consistent with the sustainable development goals. It’s time for the international community to take heed of the role PACK can play in LMICs and invest in a programme that assists these countries to deliver on universal health coverage.

Key messages.

PACK provides decision support tools and training to support frontline providers in low and middle income countries

PACK often prompts primary care health workers to claim “system agency” based on an intervention that resonates with their primary identity as clinicians

PACK’s implementation strategy can help to reconcile selective and comprehensive approaches to delivering primary care

PACK’s evaluation in pragmatic trials has facilitated rapid adoption of evidence into policy and practice in “learning health systems”

Delivering on universal primary healthcare requires a change in investments to prioritise comprehensive approaches that can meet the changing burden of disease

Acknowledgments

We thank Pearl Spiller for help with the figures and Tracy Eastman and Merrick Zwarenstein for input on an earlier draft.

Contributors and sources: LF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RC and EB provided critical comments. All authors have seen and approve the final manuscript.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that since August 2015 the KTU and BMJ have been engaged in a non-profit strategic partnership to provide continuous evidence updates for PACK, expand PACK related supported services to countries and organisations as requested, and where appropriate licence PACK content. The KTU and BMJ co-fund core positions, including a PACK global development director, and receive no profits from the partnership. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry. This article forms part of a collection on PACK sponsored by BMJ to profile the contribution of PACK across several countries.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Walsh JA, Warren KS. Selective primary health care: an interim strategy for disease control in developing countries. Soc Sci Med Econ 1980;14:145-63. 10.1016/0160-7995(80)90034-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. 2017.

- 3. Das J, Woskie L, Rajbhandari R, Abbasi K, Jha A. Rethinking assumptions about delivery of healthcare: implications for universal health coverage. BMJ 2018;361:k1716. 10.1136/bmj.k1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, et al. GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459-544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, et al. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545-602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nelson EA, Olukoya A, Scherpbier RW. Towards an integrated approach to lung health in adolescents in developing countries. Ann Trop Paediatr 2004;24:117-31. 10.1179/027249304225013394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sodhi S, Banda H, Kathyola D, et al. Evaluating a streamlined clinical tool and educational outreach intervention for health care workers in Malawi: the PALM PLUS case study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2011;11(Suppl 2):S11. 10.1186/1472-698X-11-S2-S11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tsima BM, Setlhare V, Nkomazana O. Developing the Botswana Primary Care Guideline: an integrated, symptom-based primary care guideline for the adult patient in a resource-limited setting. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:347-54. 10.2147/JMDH.S112466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wattrus C, Zepeda J, Cornick R, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Brazil. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming). 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Awotiwan A, Sword C, Eastman T, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Nigeria. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming). 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mekonnen Y, Hanlon C, Ferede S, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Ethiopia. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming). 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cornick R, Picken S, Wattrus C, et al. The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide: developing a clinical decision support tool to simplify, standardise and strengthen primary health care delivery. BMJ Global Health 2018;3:e000962 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Picken S, Hannington J, Fairall L, et al. PACK Child: A practical guide to extend the scope of integrated primary care for children. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming). 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO model list of essential medicines, 20th list. 2017. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Simelane M, Georgeu-Pepper D, Ras CJ, et al. The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) training programme—scaling up and sustaining support for health workers to improve primary care. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming). 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornick R, Wattrus C, Eastman T, et al. Crossing borders: the PACK experience of disseminating a complex health system intervention across low and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming). 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stein J, Lewin S, Fairall L, et al. Building capacity for antiretroviral delivery in South Africa: a qualitative evaluation of the PALSA PLUS nurse training programme. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:240. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, et al. Implementing nurse-initiated and managed antiretroviral treatment (NIMART) in South Africa: a qualitative process evaluation of the STRETCH trial. Implement Sci 2012;7:66. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fairall LR, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, et al. Effect of educational outreach to nurses on tuberculosis case detection and primary care of respiratory illness: pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:750-4. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zwarenstein M, Fairall LR, Lombard C, et al. Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2011;342:d2022. 10.1136/bmj.d2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, et al. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;380:889-98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fairall LR, Folb N, Timmerman V, et al. Educational outreach with an integrated clinical tool for nurse-led non-communicable chronic disease management in primary care in south africa: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002178. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Zwarenstein M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of educational outreach to primary care nurses to increase tuberculosis case detection and improve respiratory care: economic evaluation alongside a randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:277-86. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fairall L, Petersen I, Zani B, et al. CobALT research team Collaborative care for the detection and management of depression among adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: study protocol for the CobALT randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018;19:193. 10.1186/s13063-018-2517-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen I, Bhana A, Folb N, et al. PRIME-SA research team Collaborative care for the detection and management of depression among adults with hypertension in South Africa: study protocol for the PRIME-SA randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018;19:192. 10.1186/s13063-018-2518-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bachmann MO, Bateman ED, Stelmach R, et al. Integrating primary care of chronic respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease and diabetes in Brazil: Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK Brazil): study protocol for randomised controlled trials. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:4667-77. 10.21037/jtd.2018.07.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murdoch J, Curran R, Bachmann M, et al. Strengthening the quality of paediatric primary care in South Africa: protocol for process evaluation of a pilot and feasibility study of a health systems intervention. BMJ Global Health (forthcoming) 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.South African National Department of Health. Final ideal clinic manual. Version 18. SANDH, 2018.

- 29. Ivers N, Barnsley J, Upshur R, et al. “My approach to this job is...one person at a time”: perceived discordance between population-level quality targets and patient-centred care. Can Fam Physician 2014;60:258-66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923-58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. English M, Irimu G, Agweyu A, et al. Building learning health systems to accelerate research and improve outcomes of clinical care in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1001991. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fairall LR, Bachmann MO, Louwagie GM, et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:86-93. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fairall LR, Mahomed O, Bateman ED. Evidence-based decision-making for primary care: the interpretation and role of pragmatic trials. S Afr Med J 2017;107:278-9. 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i4.12413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]