Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that coordinates the production of many virulence phenotypes at high population density via quorum sensing (QS). The LuxR-type receptor RhlR plays an important role in the P. aeruginosa QS process, and there is considerable interest in the development of chemical approaches to modulate the activity of this protein. RhlR is activated by a simple, low molecular weight N-acyl L-homoserine lactone signal, N-butanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (BHL). Despite the emerging prominence of RhlR in QS pathways, there has been limited exploration of the chemical features of the BHL scaffold that are critical to its function. In the current study, we sought to systematically delineate the structure-activity relationships (SARs) driving BHL activity for the first time. A focused library of BHL analogs was designed, synthesized, and evaluated in cell-based reporter gene assays for RhlR agonism and antagonism. These investigations allowed us to define a series of SARs for BHL-type ligands and identify structural motifs critical for both activation and inhibition of the RhlR receptor. Notably, we identified agonists that have ~10-fold higher potencies in RhlR relative to BHL, are highly selective for RhlR agonism over LasR, and are active in the P. aeruginosa background. These compounds and the SARs reported herein should pave a route toward new chemical strategies to study RhlR in P. aeruginosa.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Certain bacteria are capable of coordinating population density with gene expression using an intercellular chemical signaling process known as quorum sensing (QS) (1, 2). QS allows bacteria to synchronize group-beneficial phenotypes only at high populations. In Gram-negative bacteria, QS is typically mediated by N-acyl L-homoserine lactone (AHL) signals, which are produced by LuxI-type synthases (3). These small molecules can freely diffuse out of the cell (though in select cases, export is facilitated by efflux pumps (4, 5)) and into the environment or other neighboring cells; as population density increases, the AHLs will reach an intracellular concentration at which they productively bind LuxR-type receptors. The ligand-bound LuxR-type receptors then act as transcription factors and alter gene expression levels to regulate a broad diversity of collective behaviors, including motility, biofilm formation, antibiotic and virulence factor production, and bioluminescence (6). As some of the most common agents of human infection use QS to control virulence, their QS systems have become attractive targets for infection control (7, 8). More fundamentally, identifying chemical strategies to modulate QS can provide novel entry into the molecular mechanisms of this important signaling pathway. Our laboratory and others have focused intently on developing such chemical approaches to attenuate QS in bacterial pathogens and symbionts over the past decade (9).

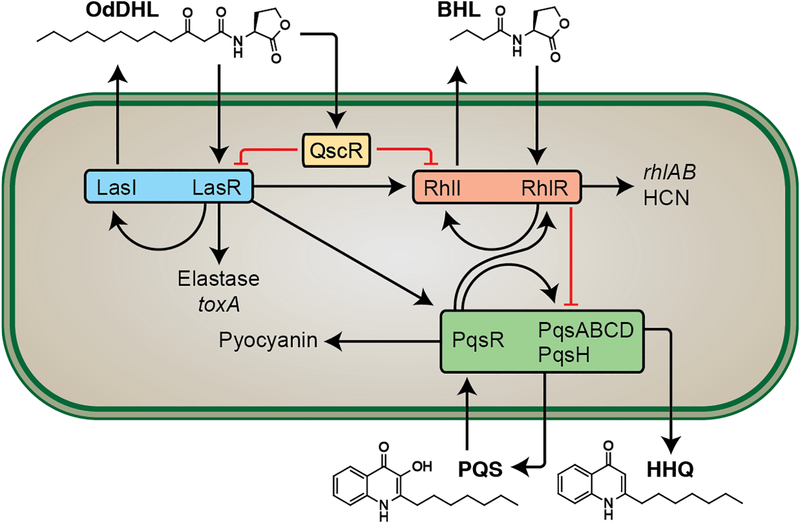

The Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most common causes of hospital-acquired infections, and uses QS to control ~10% of its genome, much of which is involved in virulence (10). P. aeruginosa utilizes a relatively complex network of receptors and chemical signals to control QS, including multiple LuxI/LuxR pairs (Figure 1). The two LuxI-type synthases, LasI and RhlI, produce N-(3-oxo)-dodecanoyl HL (OdDHL; Figure 1) and N-butanoyl HL (BHL; Figure 1), respectively (11). These two signaling molecules are recognized by their cognate LuxR-type receptors, LasR and RhlR. Both QS circuits regulate a large number of virulence factors—for example, the LasI/R system regulates the production of elastase B, alkaline protease, and exotoxin A; and the RhlI/R system regulates rhamnolipid production (a rhamnose-based biosurfactant) and the toxic exofactors hydrogen cyanide and pyocyanin (3, 11). Interestingly, OdDHL is also recognized by the orphan LuxR-type receptor, QscR, which lacks its own cognate ligand. Once ligand bound, QscR has been found to both negatively regulate LasR and activate its own unique regulon in P. aeruginosa (12). In addition to the Las and Rhl circuits, P. aeruginosa has a third circuit, Pqs, which is regulated by the lysR-type receptor PqsR (unrelated to LuxR-type receptors), the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) and the PQS biosynthetic precursor 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline (HHQ), and plays a role in the regulation of pyocyanin production (13). Adding to the complexity of QS in P. aeruginosa, each of the QS systems can positively or negatively regulate the other QS systems, and this interregulation is exquisitely sensitive to environmental factors, allowing for nimble and intricate genome regulation (14).

Figure 1:

Simplified scheme of the P. aeruginosa QS network. Black arrows represent positive feedback (autoinducer synthesis/transcriptional regulation/receptor binding, etc.). Flat red arrows represent negative regulation.

LasR is generally considered to be at the top of the P. aeruginosa QS receptor hierarchy, as it regulates genes associated with both the rhl and pqs circuits (Figure 1) (15). Due to this prominent role, its not surprising that LasR has been a primary target for the design of small molecule antagonists to block QS in this pathogen (9, 16–18). Far fewer research efforts have been directed toward the design of non-native ligands for RhlR, likely due to its perceived secondary role in QS. However, a growing number of reports have shown that both the nutrient conditions and stage of bacterial growth can reroute the QS regulatory circuitry so that RhlR instead is dominant, upending the traditional understanding of QS receptor regulation (14, 19–22). Experiments by the Bassler laboratory have further implicated the rhl system in the direct regulation of virulence factors and subsequent reduction of virulence factor production using multiple in vivo models (23, 24). In synergy with these reports, our laboratory has recently shown that inhibition of pyocyanin production can be achieved via agonism of RhlR using small molecule ligands (25).

Together, these prior results highlight that the RhlR receptor presents a significantly underdeveloped opportunity for the attenuation of P. aeruginosa virulence. To date, only a few studies have specifically focused on the development of synthetic modulators of RhlR. In 2003, Suga and co-workers showed that BHL analogs with cyclopentanone or cyclohexanone head groups and butanoyl tails exhibit potent agonistic activity towards RhlR in a P. aeruginosa reporter system (26, 27). A decade later, Bassler and co-workers reported that a meta-bromo aryl homocysteine thiolactone AHL mimic (mBTL) strongly modulated the rhl system, decreasing pyocyanin production and associated virulence (23). In 2015, we reported the screening of our in-house non-native AHL libraries for RhlR modulators and the discovery of a small collection of new RhlR ligands (28). Perhaps not surprisingly, the compounds that were capable of potent RhlR activation (e.g., D8 and S4; Figure 2) were similar in structure to its native ligand BHL. However, to date, no systematic investigation of the structure-activity relationships (SARs) dictating BHL function have been reported. Delineation of these SARs would not only allow for a deeper fundamental understanding of the features critical to BHL activity, but also provide a framework from which to design new ligands for RhlR with improved potencies.

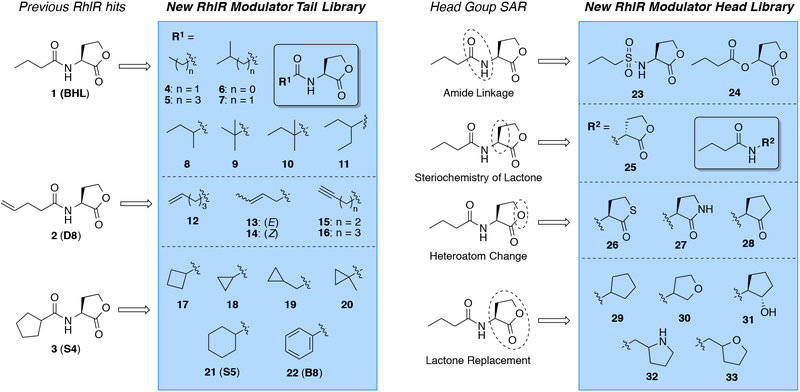

Figure 2:

Structures of RhlR native ligand 1 (BHL), two previously reported RhlR modulators used as controls (2, 3), and a focused library of compounds designed to probe SARs of RhlR (4–33). Compounds 21 and 22 were previously characterized and included for comparison in the current study (28).

Herein, we report the design, synthesis, and biological characterization of a set of BHL analog libraries with the intent of discerning SAR trends important for agonism and antagonism of the RhlR receptor in P. aeruginosa. These studies revealed the first set of detailed SAR surrounding the BHL scaffold and some of the most potent and receptor-selective non-native RhlR agonists to be reported.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RhlR-targeted library design.

An overview of our library design process and the structures of the BHL-derived library are shown in Figure 2. Our library constitutes largely new compounds. Of the subset of these compounds that have been reported previously (for references, see Table S1), none to our knowledge have been tested for direct RhlR modulation in a heterologous background (e.g., E. coli) lacking other competing LuxR-type receptors; previous screening efforts have utilized P. aeruginosa reporter strains that contain the organism’s complete and inter-connected QS network. The BHL-derived library can be divided into two groups: (1) compounds with modified tails and native lactone head groups (i.e., the tail library), and (2) compounds with modified head groups and native butanoyl tails (i.e., the head library). The tail library compounds can be further divided into three subsets based on structural similarity to either BHL or our two previously reported potent RhlR activators 2 and 3 (28). The first subset of compounds (4–11) retains the short-chain alkyl characteristics of native ligand BHL, with compounds designed to probe both tail length and alkyl substitution on the tail. We note that compound 7 (isovaleryl HL) is actually a naturally occurring AHL, first found in the symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum (29). 2-methylbutanoyl HL (8) was examined as a diastereomeric mixture. The second subset of tail-modified compounds (12–16) expands on the structural characteristics of lead pentenyl HL 2, probing alkene stereochemistry and position, as well as the presence of an alkene vs. an alkyne in the tail. Lastly, the third subset of tail modified compounds (17–22) was designed to explore structural features of lead cyclopentyl HL 3, focusing on size and the position of small carbocycles in the acyl tail.

The head group library was similarly divided into four subsets of compounds (Figure 2). While previous studies of AHL-type ligands have explored alternate head groups expanded beyond 5-membered rings (27, 30), we elected in the current study to focus exclusively on close mimics of the homoserine lactone to hopefully delineate more direct SAR for the BHL ligand. The first subset of head-group-modified compounds investigates alternate replacements for the amide linkage in the native ligand (sulfonamide 23 and ester 24). The second, one compound “sub-set” was designed to examine the importance of native stereochemistry for BHL activity (i.e., D-BHL 25). The third subset incorporates one-atom modifications to the lactone ring, replacing the lactone oxygen with sulfur (26), nitrogen (27), or a methylene (28). The fourth subset deconstructs the five-membered lactone ring even further by removing the carbonyl (29), replacing it with an alcohol (31), or varying the heteroatom location in the ring (30, 32, and 33). We note that compounds 32 and 33 (both examined as racemates) also contain an additional methylene between the ring and the amide bond; this feature was included simply due to ease of synthesis. We reasoned that these last two compounds could allow us to also explore the effect of increasing the distance the head group extends into the RhlR ligand binding pocket (assuming these close BHL analogs target the same site).

Library synthesis.

AHL library compounds were synthesized using previously established solution-phase chemistry, mainly based on carbodiimide-mediated amide coupling procedures (see Methods) (31).

E. coli reporter screens reveal BHL SARs and new RhlR agonists and antagonists.

We first evaluated the RhlR-modulatory activity of the library compounds in an E. coli reporter strain (JLD271 harboring a b-galactosidase reporter for RhlR; see Methods) in order to isolate the RhlR receptor from other QS regulators in P. aeruginosa (most notably, LasR) and thus study its response to ligands directly. We performed initial RhlR agonism and competitive RhlR antagonism screens of the library at 10 μM. Many compounds were RhlR agonists at this concentration; however, no compounds were able to inhibit RhlR activity at 10 μM (Table S2). We thus submitted all compounds to a second competitive antagonism screen at 1 mM against 10 μM BHL.

Strikingly, the primary agonism screen revealed multiple compounds with efficacies (reported as % activation, Table 1) greater than RhlR’s native ligand BHL (1) at 10 μM, which is BHL’s approximate EC50 value. The most active compounds were isovaleryl HL 7 and cyclobutyl HL 17 (86% and 79% activation, respectively), each capable of agonizing RhlR at levels equal to or greater than our previous lead RhlR agonist, 3 (S4). Scrutinizing the agonism data in terms of structural features critical for ligand activity, the most influential feature appeared to be substitution of the acyl tail α-carbon. Compounds with tertiary substituents at the α- or β-carbons appear to be well tolerated by RhlR, yet quaternary carbons abolished agonistic activity. For example, compounds 5–8 show modest to strong RhlR agonism activity (25–86%), whereas 9 and 10 were inactive as agonists. These data suggest that a specific handedness may be preferred at the a-carbon, and accordingly, that one of the diastereomers of 2-methylbutanoyl (8) is likely more active. Similarly, cyclic-tail compounds 17 and 19 were strong agonists (70% activation), but 1-methyl-cyclopropanoyl HL 20 was inactive likely due to its quaternary α-carbon. We also observed that AHLs with 3-carbon tails (e.g., propyl HL 4 and cyclopropyl HL 18) display significantly reduced abilities to activate RhlR relative to AHL homologs with straight chain or cyclic tails expanded by just one methylene (e.g., BHL (1), 17 and 19).

Table 1:

Primary RhlR assay data for BHL analog library in E. coli.a

| Compound | % activationb | % inhibitionc | Compound | % activationb | % inhibitionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (BHL) | 51 | – | 18 | 32 | – |

| 2 (D8) | 54 | – | 19 | 70 | – |

| 3 (S4) | 76 | – | 20 | 2 | 24 |

| 4 | 25 | – | 21 (S5) | 34 | – |

| 5 | 25 | – | 22 (B8)d | 1 | 31 |

| 6 | 62 | – | 23 | 1 | 55 |

| 7 | 86 | – | 24 | 0 | 6 |

| 8 | 55 | – | 25 | 2 | 11 |

| 9 | 1 | 25 | 26 | 71 | – |

| 10 | 5 | 7 | 27 | 1 | 35 |

| 11 | 28 | – | 28 | 35 | – |

| 12 | 41 | – | 29 | 0 | 45 |

| 13 | 21 | – | 30 | 0 | 20 |

| 14 | 52 | – | 31 | 2 | 12 |

| 15 | 45 | – | 32 | 0 | – |

| 16 | 34 | – | 33 | 0 | 57 |

| 17 | 79 | – |

See Methods for details. SEM of n ≥ 3 trials did not exceed ± 10%.

Library compounds screened at 10 μM. RhlR activity measured relative to BHL at 1 mM.

Library compounds screened at 1 mM in the presence of 10 μM BHL. Values expressed relative to activation of 10 μM BHL alone. – = RhlR activation observed that was ≥ to that of 10 μM BHL.

Amongst the set of compounds tested, the presence of an alkene or alkyne in the acyl tail had relatively little effect on RhlR agonistic activity (Table 1). Butenyl HL 14 and butynyl HL 15 were the most active of all compounds with unsaturated acyl tails: both displayed agonistic activities comparable BHL (1). Alkene isomers displayed different activity profiles; trans 2-butenyl derivative 13 exhibited a two-fold reduction in activity from its cis isomer 14. The “kinked’ cis alkene may enforce a tail conformation permitting 14 to bind RhlR in a manner similar to the active lead cyclopentyl HL 3. The decrease in potency observed in the longer straight chain (6 carbon) alkenyl and alkynyl HLs 12 and 16 is consistent with the prior observation that AHLs with longer acyl chains are less active RhlR agonists relative to shorter chain AHLs (26, 30).

Of the cyclic-tail AHLs tested, cyclobutanoyl HL 17 displayed the strongest RhlR-agonistic activity (79% activation; Table 1). While compound 18, with a cyclopropanoyl tail alone, fails to activate RhlR strongly (32% agonism), agonism was recovered in the one-carbon extended homolog 19 (70% activation). The larger cyclohexyl tail of 21 yielded reduced activity relative to cyclopentyl HL 3 (34% vs. 76%, respectively). Phenyl compound 22 had no agonist activity, suggesting that the tail’s rigidity at the α-carbon may be detrimental to RhlR binding.

Turning to the head-group modified BHL analogs, AHLs 26 and 28 were the only compounds to show appreciable RhlR agonism at 10 μM (Table 1). Both of these compounds maintain a carbonyl in the head group, and the more active homocysteine thiolactone analog 26 (71% activation) maintains the heteroatom electron donor. Most other head group alterations shut down all agonistic activity in RhlR at 10 μM, including replacement of the ketone in 28 to give alcohol 31 (supporting the Suga lab’s earlier result (26, 27)), replacing the native lactone with an amide in lactam 27, removing the lactone carbonyl to give cycloether 30, or extending the head group motif by an additional methylene as in compounds 32 and 33. The D-stereoisomer of BHL (25) showed marginal activity even at 1 mM (Table S2), confirming previously reported data that the stereochemistry of BHL is critical for RhlR activation (32). The AHL amide proved to be necessary for agonistic activity, as compound 24, the ester analog of BHL, was inactive. This result for BHL correlates with prior reports indicating that the AHL amide NH is essential for AHL:LuxR-type receptor binding, making a key hydrogen bond with a conserved aspartic acid in the ligand-binding site (33).

Turning next to the RhlR antagonism assay data for the tail group library (Table 1), only compounds 9, 20, and 22 were capable of inhibiting RhlR activity to a statistically significant extent (25–31%) at 1 mM. These compounds contain either a quaternary or sp2 hybridized α-carbon in their tails, suggestive that steric bulk in close proximity to the HL engenders weak antagonistic activity for short-tail AHLs. More head group library members displayed RhlR antagonism, with compounds 23, 27, 29, and 33 all showing antagonism greater than 35%. Sulfonamide 23, a 55% antagonist, has increased steric bulk adjacent to the amide NH and potentially operates through a similar mode of action as bulky tail antagonists 9 and 20. In turn, cyclolactam 27 and cyclopentyl derivative 29 lack key hydrogen bonding contacts presented by the native lactone HL for agonism (see above), and antagonize RhlR instead. Finally, the extended, tetrahydrofurfurylamine head group of 33 caused moderate RhlR antagonism (57% at 1 mM), suggesting that this positioning of the head group enforces inhibitory interactions.

BHL-type analogs can antagonize, but not agonize LasR.

We were also interested to examine the activity of the BHL library in LasR, as ligands selective for RhlR, or displaying opposite activities in each receptor (i.e., both a RhlR agonist and a LasR antagonist, and vice versa) would be useful as probes for teasing apart the closely interrelated QS circuit in P. aeruginosa (Figure 1). We thus tested the library in an E. coli LasR reporter strain using analogous methods to that for RhlR above (see Methods).

In general, our lead RhlR agonists showed negligible LasR agonism in the E. coli reporter, particularly at 10 μM (Table S3). This result is not surprising, in view of the structural differences between the native ligands for these two receptors (short chain BHL in RhlR versus long chain OdDHL in LasR). However, we found that many of the RhlR agonists, including the native ligand BHL (1), antagonize the LasR receptor instead at high concentrations (1 mM, Table S3). To our knowledge, LasR antagonism by RhlR agonists (including BHL) has not been previously reported explicitly. Interestingly, the potent RhlR agonists 7 and 17 are also some of the most active LasR antagonists found in the library (>70% inhibition). This activity profile for 7 and 17 is unique, as such compounds could be utilized to suppress LasR-associated virulence factors along with those suppressed by RhlR agonism (i.e., PQS) (25). That said, the high compound concentrations necessary for this observed activity might reduce the likelihood of implementing such dual regulation in the wild type organism.

Dose-response studies reveal highly potent RhlR agonists.

To gauge the relative potencies of the lead RhlR agonists identified in the primary assays, we submitted these compounds to dose-response analyses using the E. coli RhlR reporter. All tail group compounds that showed activities comparable to or greater than that of BHL (1), along with two head group compounds (26 and 28) with promising activities, were evaluated (Table 2). Four of the tail library members tested were found to be significantly more potent than BHL. Cyclobutyl HL 17 and isovaleryl HL 7 rivaled in potency that of cyclopentyl HL 3. Naturally occurring isovaleryl HL was the most potent activator of RhlR in this E. coli bioassay overall, with an EC50 almost 10-fold lower than BHL (1 mM vs. ~9 μM, respectively).

Table 2:

EC50 values for selected AHLs in RhlR in E. coli and P. aeruginosa.a

| E. coli | P. aeruginosa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | EC50 (μM)b | 95% Cl (μM) | EC50 (μM)b | 95% Cl (μM) |

| 1 (BHL) | 8.95 | 5.86 – 13.7 | 8.08 | 6.09 – 10.7 |

| 2 (D8) | 7.93 | 6.28 – 10.02 | – | |

| 3 (S4) | 1.58 | 1.32 – 1.90 | 1.22 | 1.03 – 1.45 |

| 5 | 10.83 | 6.59 – 17.80 | – | – |

| 6 | 4.89 | 3.67 – 6.53 | – | – |

| 7 | 1.02 | 0.67 – 1.55 | 1.42 | 1.08 – 1.86 |

| 8 | 7.77 | 5.61 – 10.8 | – | – |

| 14 | 6.93 | 5.52 – 8.71 | – | – |

| 17 | 1.78 | 1.37 – 2.31 | 1.41 | 1.14 – 1.74 |

| 19 | 2.76 | 2.23 – 3.42 | – | – |

| 26 | 4.87 | 3.46 – 6.84 | 3.82 | 2.57 – 5.66 |

| 28 | 27.4 | 16.1 – 46.6 | 14.3 | 8.76 – 23.5 |

See Methods for details. Assays performed in triplicate; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated from the SEM of n ≥ 3 trials.

For the full agonism traces, see Figures S1 and S2 for E. coli and P. aeruginosa, respectively. Additional trace characterization listed in Table S4; discussions of dose-response curve shapes are in Notes S1 and S2.

Of the head group library compounds tested (26 and 28), the homocysteine thiolactone BHL analog 26 was found to have comparable potency to BHL (Table 2). While thiolactone analogs of other AHLs have been reported to have comparable or lower agonistic activity than their parent AHL (34, 35), 26 represents to our knowledge the first thiolactone analog that is more potent than the native AHL ligand. We do note that LuxR-type receptor SdiA in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium has been reported to be more strongly activated by ligands bearing thiolactone relative to lactone head groups, but this receptor is an “orphan” type LuxR receptor that lacks a native ligand for direct comparison (36). Turning to cyclopentanone derivative 28, this analog was found to be just under 3-fold less active than BHL (p < 0.05), tracking with early reports by Suga and co-workers in P. aeruginosa (27). Despite its reduced potency, the ketone head group in 28 is not susceptible to hydrolysis (and its racemization rate should be slow (37)), marking it as a potentially useful moiety for use in the design of future, hydrolytically stable AHL analogs.

Library compounds capable of greater than 25% antagonistic activity against RhlR (23, 27, 29, and 33) were also submitted to dose-response analysis in the E. coli RhlR reporter strain versus 10 μM BHL. Overall, this set of compounds showed limited potencies (IC50 > 60 μM, dose-response curves shown in Figure S3); only the dose-response curve for cyclopentyl head group derivative 29 yielded a calculable IC50 value (52.2 μM). As this library was designed to very closely mimic the BHL scaffold, it is not surprising that we mostly identified agonists as opposed to antagonists.

Lead RhlR agonists maintain their potencies in P. aeruginosa background.

We next performed dose-response analyses on the lead RhlR agonists in P. aeruginosa to determine if they maintained their potencies in the native organism. For these experiments, we used the P. aeruginosa double synthase mutant PAO-JP2 (ΔlasIΔrhlI) harboring the RhlR reporter plasmid prhlI-LVAgfp (see Methods). Because the production of RhlR is dependent on LasR in P. aeruginosa (at least in LB medium (14)), all assays were performed in the presence of 100 nM OdDHL.

We were pleased to observe that all of the lead RhlR agonists retained similar potencies in the P. aeruginosa background relative to the E. coli RhlR reporter (Table 2). Notably, isovaleryl HL 7 and cyclobutyl HL 17 (alongside compound 3) represent, to our knowledge, the most potent non-native agonists of RhlR in P. aeruginosa. The homocysteine thiolactone BHL analog 26 showed a slight but significant improvement in potency over BHL as compared to the E. coli reporter data (p < 0.05), making it the only headgroup to prove more potent than the native ligand. As the lead RhlR agonists only display appreciable LasR antagonism at low millimolar concentrations (Table S3), the observed activities of lead compounds on RhlR in P. aeruginosa are likely not a result of indirect modulation of RhlR via LasR, but rather are due to interaction with RhlR. We note that that we have made the assumption throughout this study that these very close BHL analogs target the BHL-binding site in RhlR and engender ligand:receptor there interactions that alter RhlR function. However, we cannot discount the possibility that they also may target an allosteric site on RhlR (as either agonist or antagonists). Additional biochemical studies are required to more fully characterize their specific interactions with RhlR and are ongoing.

SUMMARY

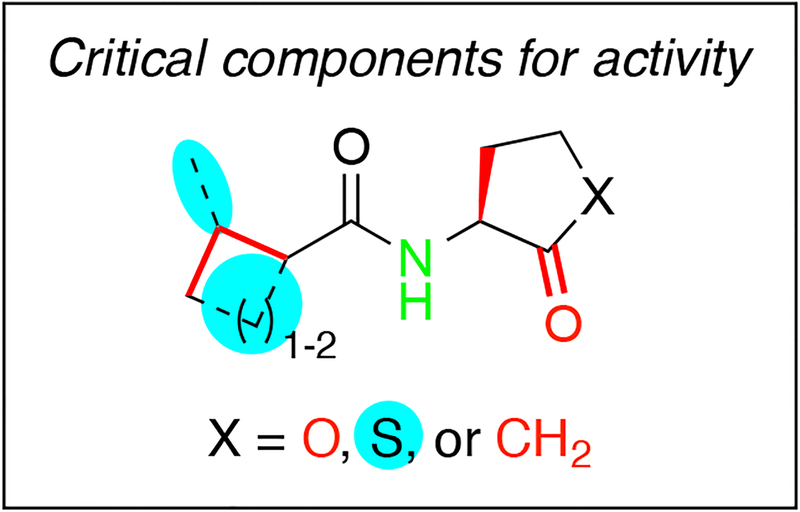

The goal of this study was to delineate key SARs dictating the activity of the natural P. aeruginosa QS signal, BHL, in the RhlR receptor. We addressed this goal via the design, synthesis, and biological characterization of a focused library of non-native AHL analogs closely based on the BHL scaffold. These experiments revealed the following SARs critical to BHL activity (Figure 3): first, the head group should maintain L-stereochemistry as well as a carbonyl adjacent to the stereocenter, and there should be an amide linkage between the head and tail groups. These requirements corroborate past studies indicating that the AHL head group carbonyl and amide make key hydrogen-bonding contacts in LuxR-type receptors with well-conserved residues (38). Second, the head group can accommodate multiple heteroatom changes alpha to the head group carbonyl, but proton donors such as an amide are not tolerated. Third, the AHL tail must contain four atoms; longer or shorter tails result in reduced agonism. The tail also must have a secondary or tertiary carbon alpha to the amide linker. We also found changes resulting in compounds with improved agonism activity over BHL. These agonists have added steric bulk relative to BHL, specifically homocysteine thiolactone head groups and cyclobutyl, cyclopentyl, or isovaleryl moieties for tail groups. Interestingly, removing or altering many of the aforementioned critical components of BHL for RhlR activation resulted in RhlR antagonists. Only the removal of the amide nitrogen resulted in compounds that had no RhlR activity. Future RhlR antagonist libraries may benefit from the removal of activating components determined in this study.

Figure 3:

Summary of key SAR trends for RhlR activators as revealed in this study. Red moieties are vital for activation. Blue moieties improve agonism beyond levels achieved by the native ligand BHL. The amide shown in green is critical for both activation and inhibition.

Finally, in the course of these experiments, we identified several compounds capable of fully agonizing RhlR with higher potencies than the native ligand BHL, both with and without modified head groups. Notably, isovaleryl HL 7 and cyclobutyl HL 17 are almost 10-fold more potent than BHL, active in P. aeruginosa, and selective for RhlR agonism. Agonism (or partial agonism) of the RhlR system has already been implicated as a possible anti-virulence strategy (23–25). As such, the structural insights and new RhlR ligands reported here will be useful in advancing new chemical probe development for further study of this important QS receptor.

METHODS

Chemistry.

Most compounds were synthesized using previously established solution-phase, N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC)-mediated amide coupling procedures (31), with a few modifications (see Supporting Information for full details).

General bacterial growth conditions and assay methods.

Bacteria were cultured in Luria−Bertani broth (LB) at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Compound stock solutions (100 mM) were prepared in DMSO. Absorbance measurements were performed using a Biotek Synergy 2 plate reader and Gen 5 software (version 1.05). Bacterial growth was quantified according to absorbance at 600 nm (OD600). All biological assay data were processed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Bacterial strains.

The following reporter strains were used: (i) E. coli strain JLD271 (ΔsdiA) (39) harboring the RhlR expression plasmid pJN105R2 (25) and the rhlI-lacZ transcriptional fusion reporter pSC11-rhlI*(25), (ii) E. coli strain JLD271 (ΔsdiA) (39) harboring the LasR expression plasmid pJN105L (40) and the lasI-lacZ transcriptional fusion reporter pSC11 (12), and (iii) P. aeruginosa strain PAO-JP2 (ΔlasIΔrhlI) (41) harboring the rhlI-gfp transcriptional fusion reporter prhlI-LVAgfp (42). Reporter strains JLD271/pJN105R2/pSC11-rhlI* and JLD271/pJN105L/pSC11 were grown in LB containing 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin and 10 μg mL−1 gentamicin.

E. coli RhlR and LasR reporter assay protocols.

The E. coli reporters JLD271/pJN105R2/pSC11-rhlI* and JLD271/pJN105L/pSC11 were used as previously described (28), with the following modifications: in the RhlR agonism reporter assay performed with substrate chlorophenol red-β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG), non-native compounds (at 10 μM or 1 mM) were compared to 1 mM BHL as the positive control; LasR reporter assays were processed using our reported protocol for the substrate ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG) (43); and LasR antagonism assays were performed versus the EC50 for OdDHL (2 nM).

P. aeruginosa RhlR reporter assay protocols.

The P. aeruginosa PAO-JP2 reporter strain harboring prhlI-LVAgfp was used as previously reported (25), with the following modifications: in the RhlR agonism assay, non-native compounds were compared to 1 mM BHL as a positive control; and RhlR antagonism assays were performed versus the EC50 for BHL (10 μM).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support for H.E.B was provided by the NIH (R01 GM109403). Financial support for R.N. was provided by Boise State University start-up funds and the NIH (R15 GM117323, P20 RR016454, and P20 GM103408). M.E.B. was funded in part by the NSF through the UW–Madison Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-1121288). J.D.M was supported in part by the UW−Madison NIH Biotechnology Training Program (T32 GM08349). NMR facilities in the UW–Madison Department of Chemistry were supported by the NSF (CHE-0342998) and a gift from P. Bender. MS facilities in the Departments of Chemistry at UW–Madison and Boise State University were supported by the NSF (CHE-9974839 and CHE-0923535, respectively).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available

Details of instrumentation, reagents, synthetic methods, primary screening data, dose-response curves, and characterization data for all new compounds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whiteley M, Diggle SP, and Greenberg EP (2017) Progress in and promise of bacterial quorum sensing research, Nature 551, 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilli A, and Bassler BL (2006) Bacterial Small-Molecule Signaling Pathways, Science 311, 1113–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster M, Sexton DJ, Diggle SP, and Greenberg EP (2013) Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing: from evolution to application, Annu. Rev. Microbiol 67, 43–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson JP, Van Delden C, and Iglewski BH (1999) Active Efflux and Diffusion Are Involved in Transport of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cell-to-Cell Signals, J. Bacteriol 181, 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JD, Gerdt JP, Eibergen NR, and Blackwell HE (2014) Active efflux influences the potency of quorum sensing inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ChemBioChem 15, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford ST, and Bassler BL (2012) Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2, a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connell KM, Hodgkinson JT, Sore HF, Welch M, Salmond GP, and Spring DR (2013) Combating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: Current Strategies for the Discovery of Novel Antibacterials, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 52, 10706–10733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clatworthy AE, Pierson E, and Hung DT (2007) Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy, Nat. Chem. Biol 3, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh MA, and Blackwell HE (2016) Chemical probes of quorum sensing: from compound development to biological discovery, FEMS Microbiol. Rev 40, 774–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strateva T, and Mitov I (2011) Contribution of an arsenal of virulence factors to pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, Ann. Microbiol 61, 717–732. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuster M, and Greenberg EP (2008) LuxR-Type Proteins in Pseuodomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing: Distinct Mechanisms with Global Implications, In Chemical Communication among Bacteria (Winans SC, and Bassler BL, Eds.), pp 133–144, ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chugani S. a., Whiteley M, Lee KM, D’Argenio D, Manoil C, and Greenberg EP (2001) QscR, a modulator of quorum-sensing signal synthesis and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2752–2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deziel E, Lepine F, Milot S, He JX, Mindrinos MN, Tompkins RG, and Rahme LG (2004) Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolines (HAQs) reveals a role for 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline in cell-to-cell communication, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1339–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welsh MA, and Blackwell HE (2016) Chemical Genetics Reveals Environment-Specific Roles for Quorum Sensing Circuits in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Cell Chem. Biol 23, 361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, and Greenberg EP (2003) Identification, Timing, and Signal Specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum-Controlled Genes: a Transcriptome Analysis, J. Bacteriol 185, 2066–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, and Blackwell HE (2008) Expanding dialogues: from natural autoinducers to non-natural analogues that modulate quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria, Chem. Soc. Rev 37, 1432–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galloway W, Hodgkinson JT, Bowden SD, Welch M, and Spring DR (2011) Quorum Sensing in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Small-Molecule Modulation of AHL and AI-2 Quorum Sensing Pathways, Chem. Rev 111, 28–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore JD, Rossi FM, Welsh MA, Nyffeler KE, and Blackwell HE (2015) A Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Quorum Sensing Modulators in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: New Insights into Mechanism, Active Efflux Susceptibility, Phenotypic Response, and Next-Generation Ligand Design, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 14626–14639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Delden C, Pesci EC, Pearson JP, and Iglewski BH (1998) Starvation Selection Restores Elastase and Rhamnolipid Production in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum-Sensing Mutant, Infect. Immun 66, 4499–4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dekimpe V, and Déziel E (2009) Revisiting the quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the transcriptional regulator RhlR regulates LasR-specific factors, Microbiology 155, 712–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PO, Jakobsen TH, Phipps R, Nielsen AK, Rybtke MT, Tolker-Nielsen T, Givskov M, Hoiby N, and Ciofu O (2010) Quorum sensing and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during lung infection of cystic fibrosis patients, PLoS ONE 5, e10115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folkesson A, Jelsbak L, Yang L, Johansen HK, Ciofu O, Høiby N, and Molin S (2012) Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cystic fibrosis airway: an evolutionary perspective, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 10, 841–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Loughlin CT, Miller LC, Siryaporn A, Drescher K, Semmelhack MF, and Bassler BL (2013) A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17981–17986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee S, Moustafa D, Smith CD, Goldberg JB, and Bassler BL (2017) The RhlR quorum-sensing receptor controls Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and biofilm development independently of its canonical homoserine lactone autoinducer, PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welsh MA, Eibergen NR, Moore JD, and Blackwell HE (2015) Small molecule disruption of quorum sensing cross-regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes major and unexpected alterations to virulence phenotypes, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 1510–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith KM, Bu Y, and Suga H (2003) Induction and Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing by Synthetic Autoinducer Analogs, Chem. Biol 10, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jog GJ, Igarashi J, and Suga H (2006) Stereoisomers of P. aeruginosa autoinducer analog to probe the regulator binding site, Chem. Biol 13, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eibergen NR, Moore JD, Mattmann ME, and Blackwell HE (2015) Potent and Selective Modulation of the RhlR Quorum Sensing Receptor by Using Non-native Ligands: An Emerging Target for Virulence Control in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ChemBioChem 16, 2348–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindemann A, Pessi G, Schaefer AL, Mattmann ME, Christensen QH, Kessler A, Hennecke H, Blackwell HE, Greenberg EP, and Harwood CS (2011) Isovaleryl-homoserine lactone, an unusual branched-chain quorum-sensing signal from the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 16765–16770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith KM, Bu Y, and Suga H (2003) Library Screening for Synthetic Agonists and Antagonists of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa Autoinducer, Chem. Biol 10, 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morkunas B, Galloway WR, Wright M, Ibbeson BM, Hodgkinson JT, O’Connell KM, Bartolucci N, Della Valle M, Welch M, and Spring DR (2012) Inhibition of the production of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factor pyocyanin in wild-type cells by quorum sensing autoinducer-mimics, Org. Biomol. Chem 10, 8452–8464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda T, Kajiyama K, Kita T, Takiguchi N, Kuroda A, Kato J, and Ohtake H (2001) The Synthesis of Optically Pure Enantiomers of N-Acyl-homoserine Lactone Autoinducers and Their Analogues, Chem. Lett, 314–315. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerdt Joseph P., McInnis Christine E., Schell Trevor L., Rossi Francis M., and Blackwell Helen E. (2014) Mutational Analysis of the Quorum-Sensing Receptor LasR Reveals Interactions that Govern Activation and Inhibition by Nonlactone Ligands, Chem. Biol, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McInnis CE, and Blackwell HE (2011) Thiolactone modulators of quorum sensing revealed through library design and screening, Bioorganic Med. Chem 19, 4820–4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boursier ME, Manson DE, Combs JB, and Blackwell HE (2018) A comparative study of non-native N-acyl L-homoserine lactone analogs in two Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing receptors that share a common native ligand yet inversely regulate virulence, Bioorganic Med. Chem, in press (DOI: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.05.018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janssens JCA, Metzger K, Daniels R, Ptacek D, Verhoeven T, Habel LW, Vanderleyden J, De Vos DE, and De Keersmaecker SCJ (2007) Synthesis of NAcyl Homoserine Lactone Analogues Reveals Strong Activators of SdiA, the Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium LuxR Homologue, Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73, 535–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glansdorp FG, Thomas GL, Lee JJK, Dutton JM, Salmond GPC, Welch M, and Spring DR (2004) Synthesis and stability of small molecule probes for Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing modulation, Org. Biomol. Chem 2, 3329–3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang R. g., Pappas KM, Brace JL, Miller PC, Oulmassov T, Molyneaux JM, Anderson JC, Bashkin JK, Winans SC, and Joachimiak A (2002) Structure of a bacterial quorum-sensing transcription factor complexed with pheromone and DNA, Nature 417, 971–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindsay A, and Ahmer BMM (2005) Effect of sdiA on Biosensors of NAcylhomoserine Lactones, J. Bacteriol 187, 5054–5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J-H, Lequette Y, and Greenberg EP (2006) Activity of purified QscR, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa orphan quorum-sensing transcription factor, Mol. Microbiol 59, 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearson JP, Pesci EC, and Iglewski BH (1997) Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes, J. Bacteriol 179, 5756–5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Kievit TR, Gillis R, Marx S, Brown C, and Iglewski BH (2001) Quorum-Sensing Genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms: Their Role and Expression Patterns, Appl. Environ. Microbiol 67, 1865–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Reilly MC, and Blackwell HE (2016) Structure-Based Design and Biological Evaluation of Triphenyl Scaffold-Based Hybrid Compounds as Hydrolytically Stable Modulators of a LuxR-Type Quorum Sensing Receptor, ACS Infect. Dis 2, 32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.