Abstract

B cells that persist for long periods of time after antigen encounter exist as either antibody‐producing plasma cells (long‐lived plasma cells, LLPCs) that reside primarily in the bone marrow or rapidly responsive memory B cells (MBCs) that reside in the spleen and circulation. Although LLPCs are thought to be non‐responsive to a secondary infection, MBCs respond to subsequent infection through the production of antibody‐secreting cells, formation of new germinal centers (GCs), and repopulation of the memory pool. Dogma suggests that MBCs express class‐switched, somatically hypermutated BCRs after undergoing a GC reaction. Yet this narrow view of MBCs has been challenged over the years and it is now well recognized that diverse MBC subsets exist in both rodents and humans. Here, we review current thoughts on the phenotypic and functional characteristics of MBCs, focusing on a population of somatically hypermutated, high affinity IgM+ MBCs that are rapidly responsive to a secondary malaria infection.

Keywords: antibody, germinal center, IgM, memory B cells, T‐dependent

Abbreviations

- GC

germinal center

- LLPC

long‐lived plasma cell

- MBC

memory B cell

- SHM

somatic hypermutation

- Tfh

T follicular helper

1. INTRODUCTION

One of the key functions of the adaptive immune system is the ability of activated lymphocytes to differentiate into functionally heterogeneous cell populations that are tailored to protect against specific pathogens. The memory lymphocytes that survive this process persist for long periods of time and programmatically “remember” prior antigen encounters through the rapid production of specific effector molecules. The differentiation of lymphocytes responsible for humoral immunity, the memory B cells (MBCs) and long‐lived plasma cells (LLPCs), involves a complex process of coordinated interactions with CD4+ T cells and other cells. These memory populations are critical for protection against numerous infections. Indeed, the presence of isotype‐switched antibodies, produced by B cells in a predominantly T‐dependent manner, is considered to be the primary hallmark of vaccine‐induced immunity.1 Yet the differentiation programs and unique functional characteristics of distinct MBC populations that generate these antibodies are only beginning to be understood.

Upon antigenic stimulation through the BCR and/or pattern recognition receptor ligation, activated naïve B cells can undergo different fate decisions. B cells can rapidly proliferate in extrafollicular foci resulting in a large population of mostly short‐lived antigen‐specific plasma cells, often called plasmablasts.2 Alternatively, activated B cells may interact with CD4+ T cells and remain in the follicle, differentiating into MBCs, through either a germinal center (GC)‐dependent or GC‐independent process.3 These T‐dependent interactions result in the formation of MBCs or antibody‐producing LLPCs that reside in the bone marrow and spleen.4 This mini review will focus on the current understanding of the generation and function of MBCs, with an emphasis on remaining questions in the field. Recent findings regarding MBC heterogeneity, with a particular focus on IgM+ MBCs, will be highlighted.

2. OVERVIEW OF B CELL FATES

B cell activation and differentiation depend upon coordinated programs of migration to defined anatomic niches where B cells interact with distinct cellular subsets. After binding to cognate antigen, activated B cells migrate to the T‐B border where they can interact with activated CD4+ T cells. B cells fated to become short‐lived plasmablasts leave the follicle and enter the extrafollicular spaces, where they divide and can undergo isotype class‐switching in a T‐dependent or independent fashion.5 Others enter the GC and proliferate after receiving a diverse array of differentiation cues from GC T follicular helper (GC Tfh) CD4+ T cells including cytokines (e.g., IL‐4, IL‐21, etc.) and costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD40L and ICOS).6 During this process, B cells integrate the multitude of signals received during their activation and subsequent interactions with CD4+ T cells, which leads to the differentiation of diverse MBC subsets and LLPCs. Although the focus of this review is the MBC, it is also important to note that LLPCs are also MBCs that continuously express antibody in the absence of re‐activation.7 Antibodies from LLPCs provide constant humoral protection against disease, yet these cells down‐regulate their BCRs and do not respond to secondary challenge.8 Therefore, understanding how to maintain or regenerate these cells continues to be an active area of investigation, especially in response to pathogens in which individuals are repeatedly exposed.

3. PHENOTYPIC HETEROGENEITY OF MBCS

MBCs persist for long periods of time and are critical contributors to subsequent antigen exposure by proliferating, rapidly forming antibody‐secreting plamsablasts and re‐entering the GC to form newly, diversified memory populations.9 Although MBCs are often described as germinal‐center derived, class‐switched and somatically hypermutated, heterogeneous populations of MBCs were described in rodents and humans over 35 years ago. At least 3 populations of MBCs were originally distinguished by surface BCR expression (IgM+IgD−, IgD+IgM−, and IgG+) in the late 1980s in rodents. Together these studies demonstrated that a quiescent population of T‐dependent, somatically hypermutated IgM+ MBCs existed and were responsive to a secondary immunization.10, 11 Shortly afterward, sequencing of IgM‐producing B cell clones from human peripheral blood demonstrated somatic hypermutation (SHM) among these cells,12 and concurrently CD27+ human MBCs were shown to secrete either IgM or IgG, indicating the presence of both MBCs in human tonsils.13 Additional studies demonstrated that somatically hypermutated IgM− and IgG‐expressing MBCs accumulated in the blood with time and are also present in human spleen.14, 15, 16, 17 Furthermore, IgM+ MBCs could be found in the splenic marginal zone in both rodents and humans.11, 18 Yet, despite multiple studies examining these cells, the existence of heterogeneous MBCs, and more specifically, germinal‐center derived IgM+ MBCs, remained controversial, as discussed by Tangye and Good.19

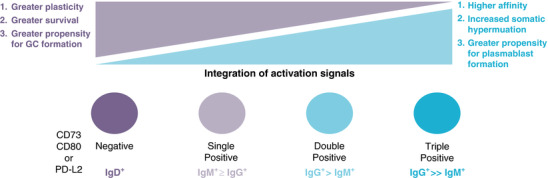

More recent phenotypic analysis has confirmed that not only do heterogeneous populations of MBCs exist in both humans and mice, but they have additional unique phenotypic attributes other than just variations in BCR isotype.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 For example, several groups have shown that populations of MBCs can express varying combinations of surface molecules associated with T cell interactions: CD73, CD80, and/or PD‐L2. Together, studies in mice have suggested a hierarchy of expression of these surface molecules such that expanded populations of IgMloIgDhi (IgD+ MBCs) that resemble naïve B cells largely do not express these molecules, whereas IgMhiIgDlo (IgM+ MBCs) more frequently express combinations of these markers and IgG MBCs predominantly express all 3 (see Fig. 1).21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29 These data further suggest that IgG+ and IgM+ MBCs develop in a germinal cell‐dependent manner, whereas IgD+ MBCs have been shown to be GC‐independent.29 Concordantly, IgD+ MBCs display very little SHM,21 whereas IgM+ cells are largely somatically mutated, however with fewer mutations than IgG+ MBCs.20, 21, 22, 23, 26 A deeper understanding of the phenotypic differences displayed by these different MBC populations will help to define the developmental and functional programs ascribed to each.

Figure 1.

Among memory B cell subsets, survival and plasticity are inversely correlated with the integration of activation signals and terminal differentiation. IgD+ MBCs persist for long periods of time, yet do not display surface markers associated with T cell interactions including CD73, CD80, and PD‐L2. However, these cells may be able to form secondary germinal centers. Populations of IgM+ and IgG+ MBCs that express only 1 of these surface markers retain some plasticity. Expression of 2 or more of the surface molecules CD73, CD80, and PD‐L2 is more frequent among IgG+ MBC than IgM+ MBCs, and cells with this phenotype are more likely to form plasmablasts during secondary responses

4. FUNCTIONAL HETEROGENEITY OF MBCS

More recently it has been recognized that distinct MBC populations exhibit unique functional attributes including survival, response kinetics, and subsequent differentiation potential. Similar to memory T cell differentiation, long‐term lymphocyte survival is inversely associated with the degree of “terminal” differentiation cues a cell has received. In general, T cells that have greater survival potential appear to have received fewer stimulating signals, express fewer effector molecules and are more plastic than their terminally differentiated effector counterparts.30 A similar paradigm is emerging for MBC populations (see Fig. 1). Isotype‐unswitched MBCs (predominantly comprised of IgD+ cells, but including a small population of IgM+ cells) have increased longevity compared with isotype‐switched (IgG+) MBCs.23, 24 Similarly, Gitlin et al.31 showed that unswitched MBCs, which have lower SHM than switched MBCs, have decreased survival. In contrast, after excluding IgD+ clones from their analyses, Jones et al.27 observed no differences in the decay rates of IgM+ and IgG+ MBCs, suggesting that these cells had similar lifespans. Analysis of antigen‐specific MBC populations during murine malaria infection further confirmed the above findings that unswitched IgD+ MBCs persist longer than IgM+ and IgG+ MBCs.21 These differences in survival may have evolved to ensure that large numbers of less‐differentiated IgD+ memory cells persist with the capacity to repopulate the memory cell pool, as described below.

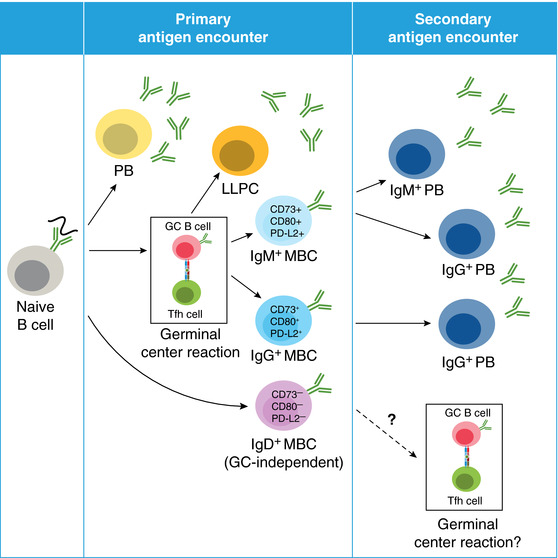

Additional debate has centered on the fate of distinct MBC subsets after re‐exposure to antigen, especially which cells rapidly form plasmablasts or re‐enter GCs.32, 33, 34 The analysis of distinct MBC subsets by both BCR isotype (IgD+, IgM+, and IgG+) and expression of surface markers (CD73, CD80, and PD‐L2) is beginning to reconcile seemingly conflicting studies. The data from multiple studies support a model (see Fig. 2) in which IgD+ MBCs re‐seed the GC, which can result in the formation of newly diversified MBCs to counteract pathogen immune evasion tactics. Alternatively, CD73+CD80+PD‐L2+ IgM+ and IgG+ MBCs are potentially limited to producing antibody‐expressing plasmablasts. In support of these hypotheses, studies utilizing either heritably labeled or transferred MBCs demonstrated that unswitched MBCs (which were predominantly IgD+) re‐seed the GC, whereas IgG+ cells rapidly formed plasmablasts.23, 24 Zuccarino‐Catania et al.25 further refined this model by demonstrating that both IgG+ and IgM+ CD80+PD‐L2+ MBCs could rapidly form plasmablasts upon a secondary in vivo challenge. Studies from our lab further confirmed these findings by examining Plasmodium‐specific MBCs during an intact rechallenge within a time frame where naïve B cells could not respond. Specifically, not only could CD73+CD80+ IgM+ MBCs form plasmablasts within 3 days of a secondary blood stage infection, but they preceeded plasmablast formation by IgG+ MBCs. These studies support a model in which the more terminally differentiated CD73+CD80+PD‐L2+ MBCs are rapid plasmablast forming cells that gain control of an infection. Although isotype‐switched cells can be found in the GC after secondary challenge,35 our findings and those of Shlomchik and colleagues have shown that IgM+ MBCs rapidly produce class switched clones within days of challenge, suggesting that the precursor identity of these IgG+ GC B cells still needs to be determined.

Figure 2.

Plasmodium‐specific MBCs. Upon primary infection, naïve B cells can differentiate into (A) short lived plasmablasts (PBs) or long‐lived plasma cells (LLPCs) or (B) memory B cells (MBCs). Distinct populations of MBCs include IgM+ and IgG+ MBCs, which display features of prior T cell interactions including surface expression of CD73, CD80, and PD‐L2 as well as somatic hypermutation. In contrast, IgD+ MBCs appear to be GC‐independent, based on lack of CD73, CD80, and PD‐L2 expression. After secondary antigen encounter, IgM+ MBCs rapidly respond by forming IgM+ and IgG+ plasmablasts, and IgG+ MBCs form IgG+ plasmablasts slightly delayed compared with IgM+ MBCs. The function of IgD+ MBCs is unclear, but these cells may form secondary germinal centers

5. ROLE OF IGM ANTIBODY DURING INFECTION

Another aspect of the secondary MBC response that may be critical to functionally diversifying the response is the unique characteristics of the antibodies themselves. Secreted IgM is expressed as either a pentamer or hexamer, endowing it with high avidity,36 and it is highly efficient at initiating complement mediated lysis and agglutination. Previous work has suggested that a single IgM can activate complement and induce erythrocyte lysis, whereas a thousand or more IgG molecules are required to perform the same function, although this may vary for different IgG isotypes.37 And remarkably, hexameric IgM is approximately 20‐fold better at inducing complement mediated lysis than pentameric IgM.38, 39 Thus, even low‐affinity IgM found early in an immune response can provide unique and important roles for the clearance of many classes of pathogens.40 Although high affinity IgG is often associated with protective humoral immunity, IgM antibodies can also be associated with protection against a wide variety of pathogens.41 For example, mice that are unable to secrete IgM are also not able to control replication of multiple bacteria species, including Borrelia hermsii and Streptococcus pneumonia,42, 43 nor are they able to neutralize Friend or influenza viruses.44, 45 In contrast, mice that lack activation‐induced cytidine deaminase, and therefore class‐switched and mutated antibodies, are protected from these pathogens.45, 46, 47 In fact, due to its unique attributes, IgM antibody may be particularly efficient at clearing bacteria or blood‐resident infections.

We propose that antibodies derived from T cell‐dependent IgM+ MBCs will be optimally protective against particulate antigens in the blood. IgM BCRs derived from Plasmodium‐specific MBCs expressed as recombinant monomers have an equally high affinity as GC‐derived Plasmodium‐specific IgG monomers.21 We are currently examining how polymerization enhances the functionality of these antibodies. Interestingly, somatically mutated IgM+ LLPCs that preferentially localize to the spleen have been described that provide protective immunity against influenza challenge, yet these appear to be generated in a GC‐independent manner, whereas Plasmodium‐specific IgM LLPCs do not.48 Therefore, to truly determine the unique roles of these various types of IgM+ B cells and their antibodies in protective immune responses, it will be essential to study these antigen‐specific IgM+ B memory cells in both mice and humans in response to specific infections.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although heterogeneous populations of MBCs were initially described over thirty years ago, it was difficult to analyze these cells without tools that allowed for the tracking of antigen‐specific MBC populations. Over the past decade, many groups have used these tools to provide a better understanding of the diverse MBC subsets that exist, including their unique phenotypic and functional attributes. These studies have also elucidated important differences in MBC survival, plasticity and responsiveness that were previously unappreciated. Since much of the work previously focused on IgG+ MBCs, it is now critical to understand less well‐studied MBC populations like IgD+ and IgM+ MBCs. As we delve into these subsets, it is now clear that a lack of terminal differentiation endows cells with enhanced plasticity. For example, our work and the work of others have demonstrated that IgM+ MBCs can rapidly class switch to IgG‐expressing plasmablasts, whereas work from Cerutti and colleagues has demonstrated that IgM+ MBCs can also switch to IgA‐expressing plasmablasts.49 Whether these IgM precursors are related or not is an open question. Cumulatively, these data further suggest that there is still much to be learned about these distinct MBC subsets, including identifying the signals that direct their development and elucidating the advantages that these cells and their antibodies provide during subsequent infections. It also remains unclear how MBCs undergo multiple rounds of SHM, although more recent data suggest that this could happen after secondary plasmablast formation perhaps in the absence of GC re‐entry50, 51 Expanded, but less differentiated MBCs would also engender the immune system with the ability to rapidly adapt to pathogenic changes over time in order to provide protection against evolved pathogens. More terminally differentiated high affinity CD73+CD80+PD‐L2+MBCs may be tailored to immediately target previously seen antigenic isoforms. In addition, it is important to maintain the functional diversity of the effector molecules generated by individual clones of MBCs. In other words, specific antibody isotypes with the same binding specificity have different functions and migrational capacities. Embracing the diversity of the unique MBC populations and the antibodies that they produce will allow us to target specific pathogens with a broader and more effective array of therapies and vaccines.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Harms Pritchard G, Pepper M. Memory B cell heterogeneity: Remembrance of things past. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;103:269–274. 10.1002/JLB.4MR0517-215R

REFERENCES

- 1. Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1055–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sze DM, Toellner KM, Garcia de Vinuesa C, Taylor DR, MacLennan IC. Intrinsic constraint on plasmablast growth and extrinsic limits of plasma cell survival. J Exp Med. 2000;192:813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Toellner KM, Jenkinson WE, Taylor DR, et al. Low‐level hypermutation in T cell‐independent germinal centers compared with high mutation rates associated with T cell‐dependent germinal centers. J Exp Med. 2002;195:383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slifka MK, Ahmed R. Long‐lived plasma cells: a mechanism for maintaining persistent antibody production. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM. The generation of antibody‐secreting plasma cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:160–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vinuesa CG, Linterman MA, Yu D, MacLennan IC. Follicular helper T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:335–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suan D, Sundling C, Brink R. Plasma cell and memory B cell differentiation from the germinal center. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;45:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manz RA, Lohning M, Cassese G, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Survival of long‐lived plasma cells is independent of antigen. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1703–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurosaki T, Kometani K, Ise W. Memory B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dell CL, Lu YX, Claflin JL. Molecular analysis of clonal stability and longevity in B cell memory. J Immunol. 1989;143:3364–3370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu YJ, Oldfield S, MacLennan IC. Memory B cells in T cell‐dependent antibody responses colonize the splenic marginal zones. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C, Stewart AK, Schwartz RS, Stollar BD. Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene expression in peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1331–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maurer D, Fischer GF, Fae I, et al. IgM and IgG but not cytokine secretion is restricted to the CD27+ B lymphocyte subset. J Immunol. 1992;148:3700–3705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klein U, Kuppers R, Rajewsky K. Evidence for a large compartment of IgM‐expressing memory B cells in humans. Blood. 1997;89:1288–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klein U, Kuppers R, Rajewsky K. Variable region gene analysis of B cell subsets derived from a 4‐year‐old child: somatically mutated memory B cells accumulate in the peripheral blood already at young age. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1383–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pascual V, Liu YJ, Magalski A, de Bouteiller O, Banchereau J, Capra JD. Analysis of somatic mutation in five B cell subsets of human tonsil. J Exp Med. 1994;180:329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tangye SG, Liu YJ, Aversa G, Phillips JH, de Vries JE. Identification of functional human splenic memory B cells by expression of CD148 and CD27. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zandvoort A, Lodewijk ME, de Boer NK, Dammers PM, Kroese FG, Timens W. CD27 expression in the human splenic marginal zone: the infant marginal zone is populated by naive B cells. Tissue Antigens. 2001;58:234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tangye SG, Good KL. Human IgM+CD27+ B cells: memory B cells or “memory” B cells?. J Immunol. 2007;179:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Budeus B, Schweigle de Reynoso S, Przekopowitz M, Hoffmann D, Seifert M, Kuppers R. Complexity of the human memory B‐cell compartment is determined by the versatility of clonal diversification in germinal centers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E5281–5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krishnamurty AT, Thouvenel CD, Portugal S, et al. Somatically hypermutated plasmodium‐specific IgM(+) memory B cells are rapid, plastic, early responders upon malaria rechallenge. Immunity. 2016;45:402–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seifert M, Kuppers R. Molecular footprints of a germinal center derivation of human IgM+(IgD+)CD27+ B cells and the dynamics of memory B cell generation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2659–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dogan I, Bertocci B, Vilmont V, et al. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zuccarino‐Catania GV, Sadanand S, Weisel FJ, et al. CD80 and PD‐L2 define functionally distinct memory B cell subsets that are independent of antibody isotype. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wrammert J, Smith K, Miller J, et al. Rapid cloning of high‐affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 2008;453:667–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones DD, Wilmore JR, Allman D. Cellular dynamics of memory B cell populations: igM+ and IgG+ memory B cells persist indefinitely as quiescent cells. J Immunol. 2015;195:4753–4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tomayko MM, Steinel NC, Anderson SM, Shlomchik MJ. Cutting edge: hierarchy of maturity of murine memory B cell subsets. J Immunol. 2010;185:7146–7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taylor JJ, Pape KA, Jenkins MK. A germinal center‐independent pathway generates unswitched memory B cells early in the primary response. J Exp Med. 2012;209:597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaech SM, Cui W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:749–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gitlin AD, von Boehmer L, Gazumyan A, Shulman Z, Oliveira TY, Nussenzweig MC. Independent roles of switching and hypermutation in the development and persistence of B lymphocyte memory. Immunity. 2016;44:769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McHeyzer‐Williams LJ, Dufaud C, McHeyzer‐Williams MG. Do memory B cells form secondary germinal centers? Impact of antibody class and quality of memory T‐cell help at recall. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017. 10.1101/cshperspect.a028878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pape KA, Jenkins MK. Do Memory B cells form secondary germinal centers? It depends. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017. 10.1101/cshperspect.a029116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shlomchik MJ. Do Memory B cells form secondary germinal center cells? Yes and no. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017. 10.1101/cshperspect.a029405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McHeyzer‐Williams LJ, Milpied PJ, Okitsu SL, McHeyzer‐Williams MG. Class‐switched memory B cells remodel BCRs within secondary germinal centers. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bendtzen K, Hansen MB, Ross C, Svenson M. High‐avidity autoantibodies to cytokines. Immunol Today. 1998;19:209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cooper NR, Nemerow GR, Mayes JT. Methods to detect and quantitate complement activation. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1983;6:195–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davis AC, Roux KH, Shulman MJ. On the structure of polymeric IgM. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Randall TD, King LB, Corley RB. The biological effects of IgM hexamer formation. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1971–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Racine R, Winslow GM. IgM in microbial infections: taken for granted?. Immunol Lett. 2009;125:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ehrenstein MR, Notley CA. The importance of natural IgM: scavenger, protector and regulator. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brown JS, Hussell T, Gilliland SM, et al. The classical pathway is the dominant complement pathway required for innate immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16969–16974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alugupalli KR, Gerstein RM, Chen J, Szomolanyi‐Tsuda E, Woodland RT, Leong JM. The resolution of relapsing fever borreliosis requires IgM and is concurrent with expansion of B1b lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2003;170:3819–3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jayasekera JP, Moseman EA, Carroll MC. Natural antibody and complement mediate neutralization of influenza virus in the absence of prior immunity. J Virol. 2007;81:3487–3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kato M, Tsuji‐Kawahara S, Kawasaki Y, et al. Class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation of virus‐neutralizing antibodies are not essential for control of friend retrovirus infection. J Virol. 2015;89:1468–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alugupalli KR, Leong JM, Woodland RT, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Gerstein RM. B1b lymphocytes confer T cell‐independent long‐lasting immunity. Immunity. 2004;21:379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harada Y, Muramatsu M, Shibata T, Honjo T, Kuroda K. Unmutated immunoglobulin M can protect mice from death by influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1779–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bohannon C, Powers R, Satyabhama L, et al. Long‐lived antigen‐induced IgM plasma cells demonstrate somatic mutations and contribute to long‐term protection. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Magri G, Comerma L, Pybus M, et al. Human secretory IgM emerges from plasma cells clonally related to gut memory B cells and targets highly diverse commensals. Immunity. 2017;47:118–134. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Di Niro R, Lee SJ, Vander Heiden JA, et al. Salmonella infection drives promiscuous B cell activation followed by extrafollicular affinity maturation. Immunity. 2015;43:120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, et al. Broadly cross‐reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2011;208:181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]