Abstract

Bladder cancer is one of the top five most common cancers diagnosed in the U.S. It is also one of the most expensive cancers to treat through the life course given its high rate of recurrence. While cigarette smoking and occupational exposures have been firmly established as risk factors, it is less certain whether modifiable lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity play roles in bladder cancer etiology and prognosis. This literature review based on a PubMed search summarizes the research to date on key dietary factors, types of physical activity, and smoking in relation to bladder cancer incidence, and discusses the potential public health implications for formalized smoking cessation programs among recently diagnosed patients. Overall, population-based research in bladder cancer is growing, and will be a key platform to inform patients diagnosed and living with bladder cancer, as well as their treating clinicians, how lifestyle changes can lead to the best outcomes possible.

Keywords: bladder cancer, diet and nutrition, physical activity, smoking and smoking cessation, lifestyle factors

Introduction

In the U.S., bladder cancer is among the top five most common cancers, with an expected 76,960 newly diagnosed cases in 2016 and 16,390 deaths [1,2]. It is also the most expensive cancer, per patient, from diagnosis to death [3], due in part to its extraordinarily high rate of recurrence [4,5]. Established risk factors for bladder cancer encompass three general areas: genetic and molecular abnormalities (specific oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes), chemical or environmental exposures (primarily cigarette smoke), and chronic irritation (such as pelvic irradiation or indwelling catheters) [6]. To date, the associations of diet and physical activity with bladder cancer risk are unclear, yet point to possible beneficial effects of these modifiable lifestyle factors. This targeted literature review will summarize the current evidence on the roles of diet, physical activity, and cigarette smoking with risk of bladder cancer, as well as any implications for potential interventions after bladder cancer diagnosis. A PubMed search was conducted using key words of bladder cancer, urothelial cancer or urothelial carcinoma, diet, nutrition, physical activity, exercise, smoking, and tobacco.

Diet and Bladder Cancer

Dietary behaviors may reduce exposure to known bladder cancer carcinogens and/or block the carcinogenic process, subsequently preventing or delaying bladder cancer occurrence. Fluid intake and vegetable and fruit consumption are of great interest in line with this notion.

Total fluid intake is expected to affect urine output and frequency of voiding, therefore modifying urinary concentrations of carcinogens and altering duration of carcinogen exposure to the bladder epithelium [7]. In a randomized trial of 65 smokers, increasing water intake for 50 days significantly decreased urinary mutagenicity [8]. Epidemiological studies on total fluid intake and bladder cancer risk have yielded conflicting results. In the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, high fluid intake (>2531 ml per day) was associated with a 49% reduction in bladder cancer risk when compared with the lowest intake (<1290 ml per day) (RR=0.51, 95% CI: 0.32–0.80) [9]. In contrast, a case-control study conducted in the U.S. reported a 41% increase in bladder cancer risk with high total fluid intake (≥2789 ml per day) compared to low intake (<1696 ml per day) [10]. A recent meta-analysis by Bai et al. summarized findings from 17 case-control and 4 cohort studies, and found no associations between total fluid intake and bladder cancer risk (overall OR=1.06, 95% CI: 0.88–1.27), yet subgroup analyses revealed significant inverse associations between intake of green tea and black tea and bladder cancer risk [11]. This finding was confirmed by the latest meta-analysis of cohort studies on tea consumption and bladder cancer risk. The meta-analysis showed a dose-dependent inverse association with an increase of every one cup of tea consumed per day, although the association was restricted to studies in Western countries (RR=0.95, 95% CI: 0.91–0.98) with a mixed tea drink, instead of specifically green or black tea [12]. Similar inconsistent results were also observed for coffee and milk consumption in relation to bladder cancer risk [13,14]. Many factors could contribute to such inconsistencies, and frequency of urination may play a critical role in determining contact time of the carcinogen with the bladder epithelium, rather than fluid intake itself. A multicenter case-control study in Spain found an inverse trend between bladder cancer risk and nighttime voiding frequency in both men and women regardless of amount of fluid consumption [15]. Examining both fluid intake and urination in a case-control study in China, Zhang et al. reported that subjects with more than 1500 ml of total fluid intake and at least 6 times of urination per day had a significant reduction in bladder cancer risk (OR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.25–0.74), compared to those who drank less than 750 ml of total fluid and urinated 3 times or less daily [16].

Vegetables and fruits contain many micronutrients and phytochemicals, which may block or suppress carcinogenesis to modify cancer risk [17]. One of these mechanisms is modulation of the phase I/II enzyme system to alter carcinogen metabolism and facilitate detoxification [17,18]. This may be particularly important for the bladder due to altering exposure to carcinogens. Additionally, nutrients and phytochemicals from fruits and vegetables have been shown to have multi-facet anticancer activities. They can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and invasion via targeting signaling pathways and boosting the anti-tumor microenvironment by inhibiting angiogenesis and reducing inflammatory responses [19,20,17]. Therefore, phytochemical-rich vegetables and fruits may not only be cancer-preventive, but also have cancer-therapeutic potential [19]. A meta-analysis of 27 observational studies published through August 2014 reported a dose-dependent reduction of bladder cancer risk with every 200 g/day increment in vegetable (RR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.87–0.97) and fruit (RR=0.91, 95% CI: 0.83–0.99) consumption [21]. However, these associations were primarily driven by findings from the case-control studies. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-compliant study summarized results from 14 cohort studies and found that bladder cancer risk was not associated with either vegetable or fruit intake [22]. Significant inverse associations with bladder cancer risk have also been reported from pooled case-control studies but not cohort studies for individual food items, such as cruciferous vegetables [23] and citrus fruits [24]. One important factor often neglected in observational studies is cooking style. Many micronutrients and phytochemicals are heat sensitive and may be destroyed or inactivated during the cooking process. In a hospital-based case-control study that examined effects of raw versus cooked cruciferous vegetables separately, significant inverse associations were only observed for raw cruciferous vegetable intake but not total or cooked counterparts [25].

Although studies have examined dietary factors and bladder cancer risk, data on dietary factors and bladder cancer survivorship are sparse. One study examined numbers of days for which consumption was at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per week in relation to a general health score in cancer survivors; the study found no associations among bladder cancer survivors [26]. Another study examined cruciferous vegetable intake in relation to bladder cancer survival and observed strong inverse associations for broccoli intake, particularly raw broccoli, with overall survival (HR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.39–0.83) and bladder cancer-specific survival (HR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.25–0.74) [27]. This finding is well supported by preclinical data on isothiocyanates, a group of promising chemopreventive phytochemicals primarily found in cruciferous vegetables [18], however the result was obtained from a small retrospective study with further validation required. During the early 1980’s and 1990’s, several clinical trials were conducted on specific micronutrients such as etretinate (a vitamin A analog), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and a mega-dose multivitamin combination [28–31]. All studies reported a significant delay or prevention of recurrence with these supplements in patients diagnosed with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Although severe side effects were also observed for these micronutrients, which limited their application, these positive results shed light on improving bladder cancer prognosis with diet or food items enriched in micronutrients and/or phytochemicals. Considering the high recurrence rate of NMIBC [32], dietary studies with a focus on bladder cancer prognosis could have a significant impact on bladder cancer outcomes.

Overall, there is no conclusive evidence to support or dispute the notion of potential beneficial roles of dietary factors in bladder cancer prevention and survival. Well-designed prospective studies are needed in this field.

Physical Activity and Bladder Cancer

Physical activity may protect against bladder cancer. Plausible mechanisms include physical activity being associated with biologic pathways that can directly influence cancer development. These include enhanced immune function, reduced chronic inflammation, increased detoxification of carcinogens, enhanced DNA repair, modified cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [33,34]. It has also been hypothesized that physical activity might indirectly decrease the risk of bladder cancer by reducing weight and helping to maintain a healthy weight [35]. Two recently published studies, one a meta-analysis [36] and the other a pooled analysis [37], reported statistically significant decreased risks of bladder cancer associated with physical activity. To note, a systematic literature review of physical activity and obesity found no associations of physical activity with bladder cancer risk in the literature, including six prospective and two retrospective studies [38].

The meta-analysis included 15 studies published from January 1975 to November 2013, which represented nearly 5.5 million subjects and 27,784 bladder cancer cases [36]. High vs. low levels of physical activity were associated with a 15% reduction in risk of bladder cancer (RR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.74–0.98). When examined by type of physical activity, the reduction in risk persisted. For recreational activity, there was a 19% reduced risk (RR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.66–0.99), and for occupational activity, there was a 10% reduced risk (RR=0.90, 95% CI: 0.76–1.07). In addition, when examining by intensity of physical activity, results were comparable. For both moderate (RR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.75–0.98) and vigorous activity (RR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.64–1.00), the risk reductions ranged from 15–20%, respectively. Increasing duration of physical activity was also suggestive of decreasing bladder cancer risk; 10%, 14%, and 17% significant reductions at 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of physical activity levels. Overall, associations by sex (male vs. female) and study design (cohort vs. case-control) were similar.

The pooled analysis combined data from 12 prospective U.S. and European cohorts representing 1.44 million subjects to examine the association of leisure-time physical activity with risk of various types of cancer [37]. Leisure-time physical activities were defined as activities done at an individual’s discretion that improve or maintain fitness or health. There were a total of 9,073 bladder cancer cases included. High levels (90th percentile) compared with low levels (10th percentile) of leisure-time physical activity were associated with a moderate 13% reduction in risk of bladder cancer (HR=0.87; 95% CI: 0.82–0.92; P for heterogeneity=.84). The association changed very minimally after adjustment for BMI (HR=0.88; 95% CI: 0.83–0.94). Finally, the associations were examined among current, former, and never smokers, and results were very similar across these three groups (P for effect modification >0.99).

To our knowledge, only one recent study has investigated the impact of physical activity on bladder cancer prognosis or survival [39]. This large study using data on 222,163 participants and 83 bladder cancer-specific deaths from the National Health Information Survey (NHIS) found that any exercise (light, moderate, or vigorous in ≥10-minute increments) was associated with a 47% decreased risk of death compared to those who reported no exercise. Results were based on a multivariable model adjusting for BMI and smoking. One limitation of this study was reduced statistical power to comprehensively examine the association between physical activity and bladder cancer death, given that the majority of participants (78%) were less than 60 years of age. Future prospective, population-based studies of bladder cancer survivors should examine specific type, duration, frequency, intensity, and timing of physical activity in relation to bladder cancer diagnosis, as well as collect more detailed physical activity data with standardized instruments measuring activity levels.

Smoking and Bladder Cancer

Tobacco smoking has long been recognized as perhaps the single most important behavioral/lifestyle risk factor associated with the development of bladder cancer, and nearly half of all bladder cancer cases in the U.S. are attributable to smoking [40].

Historical studies and landmark meta-analyses from the early 2000’s demonstrate a quantifiable risk of bladder cancer in those who smoke tobacco compared to those who do not. These studies show more than threefold increased risk in current smokers and approximately twofold increased risk in former smokers [41]. Smoking is higher than any other known risk factor for bladder cancer. These findings were validated in a 2016 meta-analysis of 89 observational studies in the last 50 years [42]. Bladder cancer risk was also associated in a dose-dependent manner with number of cigarettes smoked, with a peak risk around 15 cigarettes smoked per day. Interestingly, smoking greater than 15 cigarettes per day did not confer a significantly additive overall risk, suggesting an underlying saturation phenomenon.

Though the prevalence of tobacco smoking within the U.S. has been decreasing, the age-adjusted incidence rate of bladder cancer has remained relatively stable [43]. A 2011 study of the NIH-AARP cohort demonstrated increased risks of tobacco smoking and bladder cancer compared to earlier prospective studies in the 1960’s to 1980’s. This suggests an increase in the intensity of the association over time. The authors hypothesize that the chemical makeup of cigarettes might be increasing in carcinogenicity [44]. Cigarette composition has changed since the 1950’s, containing less nicotine and tar, but higher concentrations of nitrates and known carcinogenic N-nitrosamine byproducts [45].

Bladder cancer has historically been more common in males versus females with an almost 3:1 predominance. Early studies, particularly from the 1970’s to 1990’s, attribute this finding to known variance in smoking prevalence. Newer studies, performed in populations with more comparable gender-specific smoking prevalence show a convergence in cancer incidence. These findings indicate that males and females share comparable risk after smoking similar amounts. However, a 2009 meta-analysis suggested that tobacco smoking only partially explains the male excess in bladder cancer incidence. An explanation for this difference has not been well-elucidated, but theories suggest stronger occupational influences, as well as biogenetic susceptibilities [46].

Given the large body of evidence outlined above, public health awareness of bladder cancer as a tobacco-related disease is poor and is notably lower compared to other tobacco-related illnesses. In a survey of 535 urology patients, 94% of patients recognized the association of smoking and lung cancer, yet only a quarter of those patients understood the association between smoking and bladder cancer [47].

In addition to tobacco smoking’s association with bladder cancer risk, it is also associated with bladder cancer prognosis. Current and former smokers diagnosed with NMIBC exhibit increased recurrence and progression rates than never smokers, perhaps as a function of their total cumulative exposure [48–50], and are 4 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to die of bladder cancer compared with never smokers [39]. Current smokers additionally tend to fare worse than former smokers and nonsmokers after similar treatments with transurethral resection and intravesical chemotherapy. In the context of muscle-invasive disease, current smokers experience higher rates of treatment-related complications and morbidity, and a 1.4-fold increased risk of bladder cancer-specific mortality [51].

Health care providers, particularly urologists, have an opportunity to assume a key role in the secondary prevention of bladder cancer, as well as other cancers and medical conditions associated with tobacco smoking, through smoking cessation counseling. Exceptionally high cessation rates of 40–96% observed among patients with new diagnoses of lung or oropharyngeal cancers [52–59] speak to the potential efforts in this context. One population-based study found smokers with a new diagnosis of bladder cancer were approximately five times more likely to quit as smokers in the general population. Patients cited the bladder cancer diagnosis and the advice of their urologist as the most common reasons for cessation [60]. Evidence suggesting potentially decreased recurrence rates among patients with NMIBC [61,48] may be particularly relevant in the reinforcement of bladder cancer diagnosis as a “teachable moment.” Nevertheless, greater attention is needed on this topic in the bladder cancer clinic. American urologists are particularly deficient in cessation counselling, with a majority of practitioners never addressing tobacco cessation, and almost 40% expressing the belief that it would not affect disease course or alter treatment outcomes [62]. In one study demonstrating the gaps in current practice, almost 95% of active smokers newly diagnosed with tobacco-related urologic cancer were not counseled in tobacco cessation at the time of their initial visit, despite the fact that as few as five minutes of cessation intervention can increase the likelihood of quitting by fourfold [63]. Greater attention to this component of patient counseling may provide benefits not only in terms of bladder cancer outcomes, but overall health.

The Bladder Cancer Epidemiology, Wellness, and Lifestyle Study (Be-Well Study)

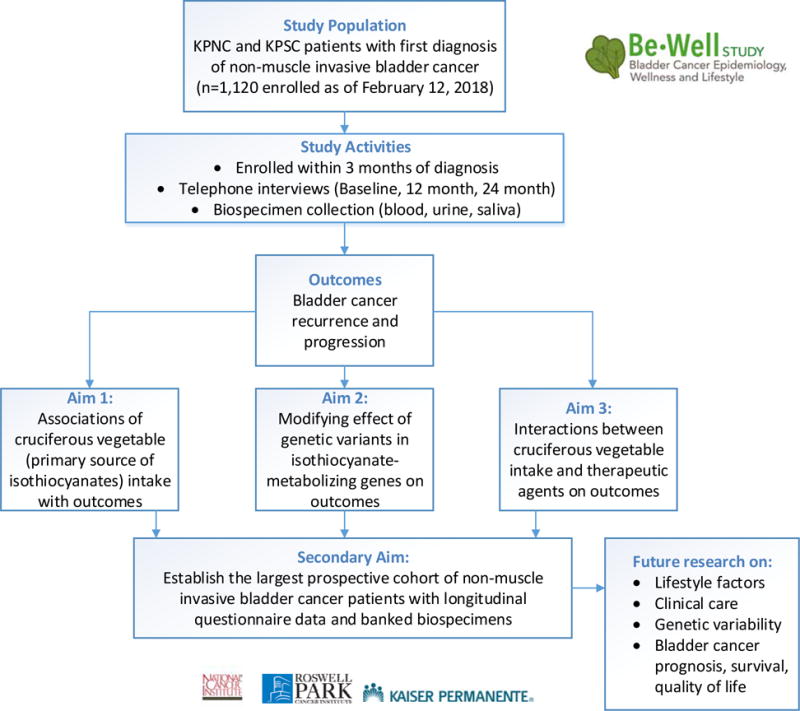

As this review suggests, the evidence on the role of several lifestyle and nutritional factors and bladder cancer prognosis and survival is sparse. To address these gaps, the Be-Well Study, a prospective cohort study of patients with newly diagnosed NMIBC, began in 2014 with funding from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA172855; MPI: Kwan, Tang, Kushi). The overall aim of Be-Well is to examine the role of nutritional, lifestyle, and genetic factors in bladder cancer treatment and outcomes (Figure 1). Patients are being actively recruited from Kaiser Permanente (KP), the largest integrated health delivery system in the U.S., in KP Northern and Southern California. Prospective data are being collected at three points post-diagnosis on self-reported lifestyle and nutritional factors, along with confirmed recurrence, progression, and survival outcomes. Blood, urine, and saliva are also being obtained in a prospective manner to provide accompanying genetic and biomarker data. It is anticipated that Be-Well will establish one of the largest, most comprehensive prospective cohort studies of bladder cancer patients with NMIBC to help answer critical questions related to prognosis, quality of life, and care in patients diagnosed with early-stage bladder cancer.

Figure 1.

Overview of Bladder Cancer Epidemiology, Wellness, and Lifestyle Study (Be-Well Study), Funded by the National Cancer Institute, R01CA172855

Conclusion and Future Steps

Potentially modifiable lifestyle factors and health behaviors including diet, physical activity, and smoking have been associated with bladder cancer carcinogenesis to varying degrees [64]. These include increased fluid intake, more vegetable and fruit consumption, and regular physical activity. The impact of these factors on prognosis has been relatively unexplored, especially for diet and physical activity. More well-designed studies with precise behavioral measurements are necessary to investigate possible beneficial effects of lifestyle on incidence and outcomes. Results from the ongoing Be-Well Study of bladder cancer survivors could inform future interventions in this area. Encouragingly, a pilot intervention study found that telephone- or Skype-based dietary counseling is able to increase total vegetable intake among bladder cancer patients diagnosed with NMIBC, showing the feasibility of dietary intervention programs among bladder cancer survivors [65]. Finally, while primary prevention from continued broad-based tobacco control policies are important, evidence suggests potentially high impact opportunities for secondary prevention through a more systematic implementation of smoking cessation in the clinic as a component of bladder cancer care. In conclusion, population-based, observational research in bladder cancer is growing, which will contribute to further knowledge on how patients diagnosed and living with bladder cancer can modify their lifestyle to ensure the best outcomes possible.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janise M. Roh, MSW, MPH and Michelle Ross, MPH for administrative and editorial support.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html.

- 3.Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Redaelli A, Laskin B, Hauser R. The health economics of bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the published literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21(18):1315–1330. doi: 10.1007/BF03262330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avritscher EB, Cooksley CD, Grossman HB, Sabichi AL, Hamblin L, Dinney CP, Elting LS. Clinical model of lifetime cost of treating bladder cancer and associated complications. Urology. 2006;68(3):549–553. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barocas DA, Globe DR, Colayco DC, Onyenwenyi A, Bruno AS, Bramley TJ, Spear RJ. Surveillance and treatment of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the USA. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:421709. doi: 10.1155/2012/421709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman DS. Challenges in the treatment of bladder cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17Suppl 5:v106–112. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braver DJ, Modan M, Chetrit A, Lusky A, Braf Z. Drinking, micturition habits, and urine concentration as potential risk factors in urinary bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78(3):437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buendia Jimenez I, Richardot P, Picard P, Lepicard EM, De Meo M, Talaska G. Effect of Increased Water Intake on Urinary DNA Adduct Levels and Mutagenicity in Smokers: A Randomized Study. Disease markers. 2015;2015:478150. doi: 10.1155/2015/478150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaud DS, Spiegelman D, Clinton SK, Rimm EB, Curhan GC, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Fluid intake and the risk of bladder cancer in men. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;340(18):1390–1397. doi: 10.1056/nejm199905063401803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Wu X, Kamat A, Barton Grossman H, Dinney CP, Lin J. Fluid intake, genetic variants of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, and bladder cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(11):2372–2380. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai Y, Yuan H, Li J, Tang Y, Pu C, Han P. Relationship between bladder cancer and total fluid intake: a meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. World journal of surgical oncology. 2014;12:223. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang YF, Xu Q, Lu J, Wang P, Zhang HW, Zhou L, Ma XQ, Zhou YH. Tea consumption and the incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(4):353–362. doi: 10.1097/cej.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wierzejska R. Coffee consumption vs. cancer risk - a review of scientific data. Roczniki Panstwowego Zakladu Higieny. 2015;66(4):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao QQ, Dai Y, Lin YW, Qin J, Xie LP, Zheng XY. Milk consumption and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. Nutrition and cancer. 2011;63(8):1263–1271. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.614716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverman DT, Alguacil J, Rothman N, Real FX, Garcia-Closas M, Cantor KP, Malats N, Tardon A, Serra C, Garcia-Closas R, Carrato A, Lloreta J, Samanic C, Dosemeci M, Kogevinas M. Does increased urination frequency protect against bladder cancer? Int J Cancer. 2008;123(7):1644–1648. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Xiang YB, Fang RR, Cheng JR, Yuan JM, Gao YT. [Total fluid intake, urination frequency and risk of bladder cancer: a population-based case-control study in urban Shanghai] Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2010;31(10):1120–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surh YJ. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(10):768–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang L, Zhang Y. Isothiocyanates in the chemoprevention of bladder cancer. Current drug metabolism. 2004;5(2):193–201. doi: 10.2174/1389200043489027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beliveau R, Gingras D. Role of nutrition in preventing cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(11):1905–1911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorai T, Aggarwal BB. Role of chemopreventive agents in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2004;215(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Wang XC, Hu GH, Guo ZF, Lai P, Xu L, Huang TB, Xu YF. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of bladder cancer: an updated meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(6):508–516. doi: 10.1097/cej.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu C, Zeng XT, Liu TZ, Zhang C, Yang ZH, Li S, Chen XY. Fruits and vegetables intake and risk of bladder cancer: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine. 2015;94(17):e759. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Mao Q, Lin Y, Zhou F, Xie L. The association of cruciferous vegetables intake and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. World journal of urology. 2013;31(1):127–133. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang S, Lv G, Chen W, Jiang J, Wang J. Citrus fruit intake and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies. International journal of food sciences and nutrition. 2014;65(7):893–898. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2014.917151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang L, Zirpoli GR, Guru K, Moysich KB, Zhang Y, Ambrosone CB, McCann SE. Consumption of raw cruciferous vegetables is inversely associated with bladder cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(4):938–944. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(13):2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang L, Zirpoli GR, Guru K, Moysich KB, Zhang Y, Ambrosone CB, McCann SE. Intake of cruciferous vegetables modifies bladder cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(7):1806–1811. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-10-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alfthan O, Tarkkanen J, Grohn P, Heinonen E, Pyrhonen S, Saila K. Tigason (etretinate) in prevention of recurrence of superficial bladder tumors. A double-blind clinical trial. European urology. 1983;9(1):6–9. doi: 10.1159/000474033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Studer UE, Jenzer S, Biedermann C, Chollet D, Kraft R, von Toggenburg H, Vonbank F. Adjuvant treatment with a vitamin A analogue (etretinate) after transurethral resection of superficial bladder tumors. Final analysis of a prospective, randomized multicenter trial in Switzerland. European urology. 1995;28(4):284–290. doi: 10.1159/000475068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byar D, Blackard C. Comparisons of placebo, pyridoxine, and topical thiotepa in preventing recurrence of stage I bladder cancer. Urology. 1977;10(6):556–561. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(77)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamm DL, Riggs DR, Shriver JS, vanGilder PF, Rach JF, DeHaven JI. Megadose vitamins in bladder cancer: a double-blind clinical trial. The Journal of urology. 1994;151(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Josephson DY, Pasin E, Stein JP. Superficial bladder cancer: part 1. Update on etiology, classification and natural history. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2006;6(12):1723–1734. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.12.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers CJ, Colbert LH, Greiner JW, Perkins SN, Hursting SD. Physical activity and cancer prevention : pathways and targets for intervention. Sports Med. 2008;38(4):271–296. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838040-00002. doi:3842 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Lynch BM. State of the epidemiological evidence on physical activity and cancer prevention. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;46(14):2593–2604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koebnick C, Michaud D, Moore SC, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Ballard-Barbash R, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF. Body Mass Index, Physical Activity, and Bladder Cancer in a Large Prospective Study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17(5):1214–1221. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-08-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keimling M, Behrens G, Schmid D, Jochem C, Leitzmann MF. The association between physical activity and bladder cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Cancer. 2014;110(7):1862–1870. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore SC, Lee IM, Weiderpass E, Campbell PT, Sampson JN, Kitahara CM, Keadle SK, Arem H, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Adami H-O, Blair CK, Borch KB, Boyd E, Check DP, Fournier A, Freedman ND, Gunter M, Johannson M, Khaw K-T, Linet MS, Orsini N, Park Y, Riboli E, Robien K, Schairer C, Sesso H, Spriggs M, Van Dusen R, Wolk A, Matthews CE, Patel AV. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity With Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(6):816. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noguchi JL, Liss MA, Parsons JK. Obesity, Physical Activity and Bladder Cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2015;16(10):74. doi: 10.1007/s11934-015-0546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liss MA, White M, Natarajan L, Parsons JK. Exercise Decreases and Smoking Increases Bladder Cancer Mortality. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(3):391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverman DT, Devesa SS, Moore LE, Rothman N. Bladder Cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, editors. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd. Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York: 2006. pp. 1101–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeegers MP, Tan FE, Dorant E, van Den Brandt PA. The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2000;89(3):630–639. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::aid-cncr19>3.3.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Osch FH, Jochems SH, van Schooten FJ, Bryan RT, Zeegers MP. Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(3):857–870. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Znaor A, Jemal A, Bray F. Bladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Overview and Recent Trends. European urology. 2017;71(1):96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freedman ND, Silverman DT, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC. Association between smoking and risk of bladder cancer among men and women. JAMA. 2011;306(7):737–745. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I, El-Bayoumy K. The less harmful cigarette: a controversial issue. a tribute to Ernst L. Wynder. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14(7):767–790. doi: 10.1021/tx000260u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hemelt M, Yamamoto H, Cheng KK, Zeegers MP. The effect of smoking on the male excess of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis and geographical analyses. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(2):412–419. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bjurlin MA, Cohn MR, Freeman VL, Lombardo LM, Hurley SD, Hollowell CM. Ethnicity and smoking status are associated with awareness of smoking related genitourinary diseases. The Journal of urology. 2012;188(3):724–728. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleshner N, Garland J, Moadel A, Herr H, Ostroff J, Trambert R, O’Sullivan M, Russo P. Influence of smoking status on the disease-related outcomes of patients with tobacco-associated superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer. 1999;86(11):2337–2345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li HM, Azhati B, Rexiati M, Wang WG, Li XD, Liu Q, Wang YJ. Impact of smoking status and cumulative smoking exposure on tumor recurrence of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lammers RJ, Witjes WP, Hendricksen K, Caris CT, Janzing-Pastors MH, Witjes JA. Smoking status is a risk factor for recurrence after transurethral resection of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. European urology. 2011;60(4):713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sosnowski R, Przewozniak K. The role of the urologist in smoking cessation: why is it important? Urol Oncol. 2015;33(1):30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evangelista LS, Sarna L, Brecht ML, Padilla G, Chen J. Health perceptions and risk behaviors of lung cancer survivors. Heart Lung. 2003;32(2):131–139. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2003.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duffy SA, Terrell JE, Valenstein M, Ronis DL, Copeland LA, Connors M. Effect of smoking, alcohol, and depression on the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(3):140–147. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allison PJ. Factors associated with smoking and alcohol consumption following treatment for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(6):513–520. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gritz ER, Schacherer C, Koehly L, Nielsen IR, Abemayor E. Smoking withdrawal and relapse in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1999;21(5):420–427. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199908)21:5<420::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vander Ark W, DiNardo LJ, Oliver DS. Factors affecting smoking cessation in patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(7):888–892. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dresler CM, Bailey M, Roper CR, Patterson GA, Cooper JD. Smoking cessation and lung cancer resection. Chest. 1996;110(5):1199–1202. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ostroff JS, Jacobsen PB, Moadel AB, Spiro RH, Shah JP, Strong EW, Kraus DH, Schantz SP. Prevalence and predictors of continued tobacco use after treatment of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 1995;75(2):569–576. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950115)75:2<569::aid-cncr2820750221>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gritz ER, Nisenbaum R, Elashoff RE, Holmes EC. Smoking behavior following diagnosis in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1991;2(2):105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00053129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bassett JC, Gore JL, Chi AC, Kwan L, McCarthy W, Chamie K, Saigal CS. Impact of a bladder cancer diagnosis on smoking behavior. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(15):1871–1878. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen CH, Shun CT, Huang KH, Huang CY, Tsai YC, Yu HJ, Pu YS. Stopping smoking might reduce tumour recurrence in nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100(2):281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06873.x. discussion 286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bjurlin MA, Goble SM, Hollowell CM. Smoking cessation assistance for patients with bladder cancer: a national survey of American urologists. The Journal of urology. 2010;184(5):1901–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bjurlin MA, Cohn MR, Kim DY, Freeman VL, Lombardo L, Hurley SD, Hollowell CM. Brief smoking cessation intervention: a prospective trial in the urology setting. The Journal of urology. 2013;189(5):1843–1849. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al-Zalabani AH, Stewart KF, Wesselius A, Schols AM, Zeegers MP. Modifiable risk factors for the prevention of bladder cancer: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(9):811–851. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0138-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parsons JK, Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Newman VA, Barbier L, Mohler J, Rock CL, Heath DD, Guru K, Jameson MB, Li H, Mirheydar H, Holmes MA, Marshall J. A randomized pilot trial of dietary modification for the chemoprevention of noninvasive bladder cancer: the dietary intervention in bladder cancer study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6(9):971–978. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]