Abstract

Background

Although chronic lymphocytic leukemia is basically a B cell disease, its pathophysiology and evolution are thought to be significantly influenced by T cells, as these are probably the most important interaction partner of neoplastic B cells, participating in their expansion, differentiation and survival. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells may also drive functional and phenotypic changes of non-malignant T cells. There are few data about the association between memory T cells and prognosis, especially related to ZAP-70, a common reliable surrogate of the gold standard chronic lymphocytic leukemia prognostic markers.

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the expression of ZAP-70 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients is associated with abnormal patterns of the distribution of naïve and memory T cells related to crosstalk between these cells.

Methods

In this cross-sectional, controlled study, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia were compared with healthy blood donors regarding the expression of ZAP-70 and the distribution of naïve and memory T cell subsets in peripheral blood as measured by flow cytometry.

Results

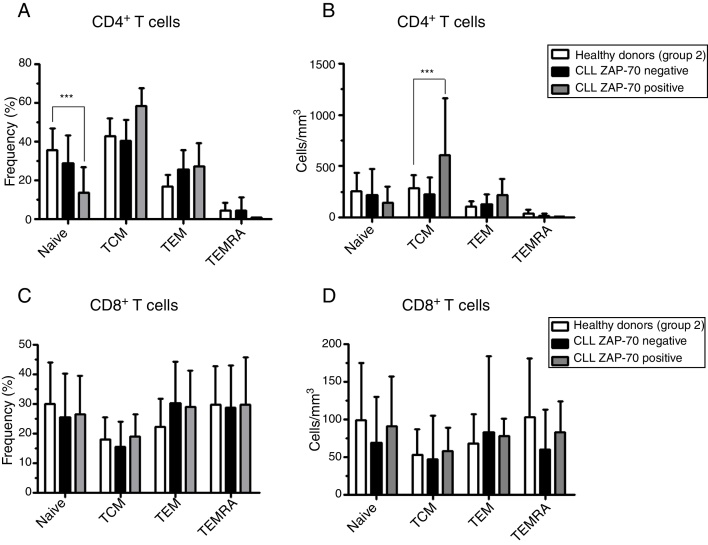

ZAP-70 positive patients presented an increased frequency and absolute number of central memory CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ T cells, compared to ZAP-70 negative patients and age-matched apparently healthy donors.

Conclusions

Because central memory CD4+ T cells are located in lymph nodes and express CD40L, we consider that malignant ZAP-70-positive B cells may receive beneficial signals from central memory CD4+ T cells as they accumulate, which could contribute to more aggressive disease.

Keywords: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, ZAP-70 protein-tyrosine kinase, Memory T cells

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common lymphoproliferative neoplasm in Western countries; it is characterized by an accumulation of mature CD5+ B cells in hematopoietic tissue due to the imbalance in the rates of proliferation and apoptosis. It has been reported that genetic predisposition, mutations, familial history, environmental factors and clonal evolution induced by antigens and/or auto-antigens are elements related to the etiology of the disease.1, 2, 3

The clinical course of CLL is heterogeneous and varies between individuals.1, 4 Several clinical and laboratory data are considered prognostic markers, including Rai and Binet staging, lymphocyte count doubling time, cytogenetics, different genetic mutations, zeta-chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP-70) expression and the Ig heavy chain V-III region VH26 (IgVH) gene mutational status.3, 5, 6, 7, 8 Of these, ZAP-70 expression, detected by flow cytometry, is commonly used as a reliable surrogate for gold standard prognostic markers.8

Although CLL is basically a B cell disease, it has been proposed that its pathophysiology and evolution are significantly influenced by T cells as they participate in their expansion, differentiation and survival, which may also influence T lymphocyte function and phenotype,9, 10 with the accumulation of memory T cells in CLL patients.11, 12 However there are few data about the association between memory T cells and the prognosis of CLL, especially related to ZAP-70.

Thus, this study analyzed the peripheral T cell compartment of CLL patients, to evaluate whether ZAP-70 expression is associated with an abnormal distribution of naïve and memory T cells related to the crosstalk between these cells, and consequently to the prognosis of the disease.

Methods

Study design, ethics and setting

This controlled cross-sectional study compared CLL patients with healthy blood donors regarding the distribution of naïve and memory T-cell subsets in peripheral blood. The study was conducted in two referral centers for hematology and oncology in Brazil, one private and the other a public teaching institution.

All healthy blood donors and patients signed informed consent forms thereby agreeing to participate in this study. The review boards of both institutions reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Healthy donors and patients

The case group of this study were all adult patients admitted for the diagnosis of CLL from September 2011 to September 2012. The control group comprised blood donors from the same institutions during the same period.

A volume of approximately 10 mL of peripheral blood (PB) was collected from all participants in tubes with anticoagulant heparin or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for flow cytometry. In the blood banks, the sample was collected after voluntary donations.

Flow cytometry assay

The flow cytometry assay used in this study for the evaluation of the ZAP-70 expression was performed in the Flow Cytometry Laboratory of the Clinical Pathology Laboratory of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein. The technical procedures and flow cytometry settings followed standard operating procedures (SOP) previously validated in the laboratory and the quality was monitored by internal and external quality controls as published by the American College of Pathology (CAP) and United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service (UKNEQAS).

The expression of ZAP-70 in B-cell CLL patients was always evaluated in parallel to a sample of peripheral blood from a healthy donor in order to validate the intracytoplasmic reaction and the ZAP-70 antigenic expression in T-cells (positive) and B cells (negative).

All fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were validated before use according to the reaction specificity and the best volume capable of providing the antigen–antibody binding saturation (titration).

Characterization of naïve and memory T cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy donors and CLL patients were obtained and purified using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Sweden) and density gradient centrifugation.13

The cell concentration and viability were assessed using an optical microscope, Neubauer chamber and trypan blue. An aliquot of 1 × 106 cells were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD45RA, anti-CD62L monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) conjugated with peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), allophycocyanin cyanine 7 (APC-Cy7), phycoerythrin cyanine 7 (PE-Cy7), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and phycoerythrin (PE), respectively (Becton, Dickinson San Jose, CA, USA). After incubation and washing, samples were analyzed by flow cytometry in a BDFACS Canto II apparatus (Becton, Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) using the FlowJo software – (Tree Star, Inc.).

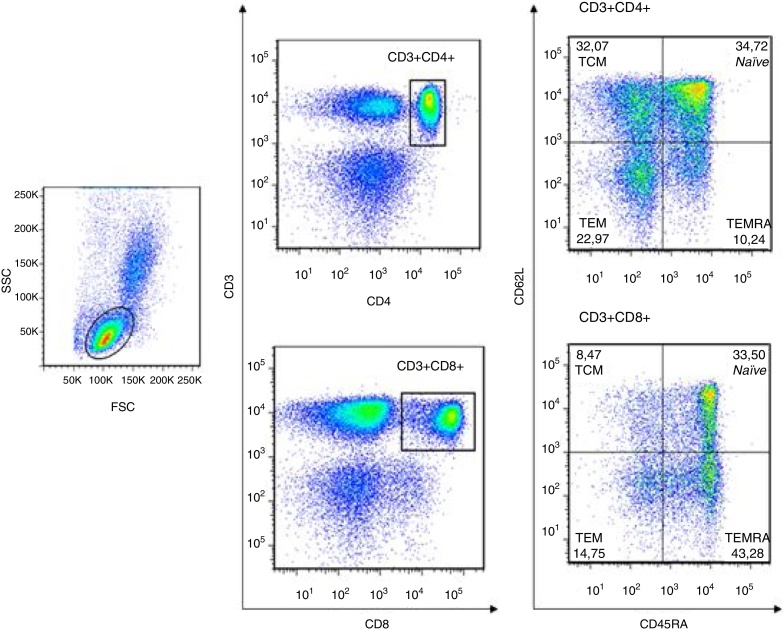

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were respectively determined by double positivity of CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+. Moreover, CD45RA and CD62L expressions were used to identify naïve T cells (CD45RA+CD62L+), central memory T cells (TCM; CD45RA−CD62L+), effector memory T cells (TEM; CD45RA−CD62L−) and terminal effector memory T cells (TEMRA; CD45RA+CD62L−) (Figure 1). This strategy was used for both healthy donors and CLL patients.

Figure 1.

Characterization of naïve and memory T cells in peripheral blood of healthy donors and chronic lymphocyte leukemia (CLL) patients by flow cytometry. The lymphocyte region was evaluated considering the forward and side scatter of cells. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were respectively determined by double positivity of CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+, and the CD45RA and CD62L expression patterns were used to identity naïve T cells (CD45RA+CD62L+), central memory T cells (CD45RA−CD62L+), effector memory T cells (CD45RA−CD62L−) and terminal effector memory T cells (CD45RA+CD62L−). For standardization, 50,000 events were acquired in the CD3+ T-cell population. This strategy was representative for healthy donors and CLL patients.

ZAP-70 expression in CLL patients

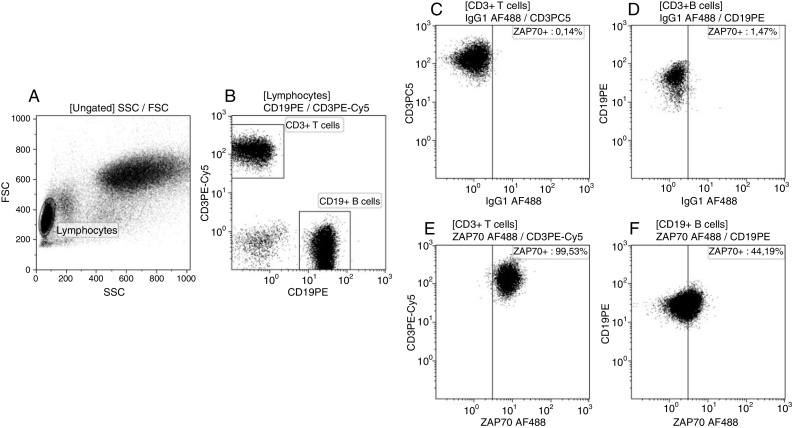

For the ZAP-70 flow cytometry assay, 5 × 106 PB cells from healthy donors and CLL patients were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD19 mAbs and conjugated with phycoerythrin cyanine (PE-Cy5) and PE, respectively (Beckman Coulter). For cytoplasmic staining, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti-ZAP-70 mAb conjugated with Alexa-Fluor488 (clone 1E7.2, Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed in a Cytomics FC500 apparatus (Beckman Coulter – Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Detection of ZAP-70 expression in healthy donors and chronic lymphocyte leukemia (CLL) patients. An aliquot of 5 × 105 peripheral blood cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies (CD19PE, CD3PE-Cy5, intracellular mouse IgG1 AF488 and intracellular ZAP-70 AF488) and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) First a gate in the lymphocyte region was created according to forward and side scatter to better identify the specific populations. (B) Following the gate strategy, CD19+ B cells and CD3+ T cells were characterized in the lymphocyte gate. The definition of negative fluorescence by mouse IgG1 AF488 (C) in CD3+ T cells and (D) in CD19+ B cells. (E) ZAP-70 positive expression in normal CD3+ T cells and (F) in neoplastic CD19+ B cells. The ZAP-70 expression in normal T cells of CLL patients was used as the internal control of staining reaction. A total of 50,000 events was acquired for all counts.

The cut-off for ZAP-70 positivity was based on published data, which recommends positivity when more than 20% of neoplastic B lymphocytes express ZAP-70.8

To standardize the technique, the ZAP-70 expression was always analyzed in the samples of healthy donors in parallel to CLL patients. Furthermore, the isotype control for Alexa-Fluor488 was used as a negative control of the reaction, while the expression of ZAP-70 on normal T lymphocytes was considered the positive control.14

Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of the data was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for each type of cell and there was no statistical significance to reject the assumption of normality. The comparison between cell types in total was performed using the paired Student t-test and the comparison between the cell subpopulations was performed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison. Comparison between groups (healthy and case) and cell types or subtypes were achieved using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison when necessary. Statistical differences were considered significant when p-values were <0.05.

Results

In the study period, 21 CLL patients and 43 controls were enrolled. In the control group, 17 patients were over 40 years old. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the control group and the clinical and laboratory data of the CLL patients are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of healthy donors.

| Characteristic | Total | Over 40-year olds |

|---|---|---|

| Patients – n (%) | 43 (100) | 17 (100) |

| Sex – n (%) | ||

| Male | 26 (60.5) | 9 (52.9) |

| Female | 17 (39.5) | 8 (47.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 36 | 55 |

| Range | 19–72 | 41–72 |

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory data of chronic lymphocyte leukemia patients.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| n | 21 |

| Sex – n (%) | |

| Male | 16 (76.2) |

| Female | 5 (23.8) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 64 |

| Range | 46–88 |

| Leucocytes (×103/μL) | |

| Median | 24.46 |

| Range | 2.60–61.00 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/μL) – n (%) | |

| Median | 20,465.0 (78.3) |

| Range | 1.609 (41.7)-53,741.0 (92.0) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |

| Median | 13.6 |

| Range | 8.5–16.7 |

| Hematocrit (fL) | |

| Median | 39.8 |

| Range | 25.6–54.2 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | |

| Median | 205 |

| Range | 32,000–265,000 |

| ZAP-70 expression – n (%) | |

| Negative | 16 (76.2) |

| Positive | 5 (23.8) |

Distribution profile of naïve and memory T cells

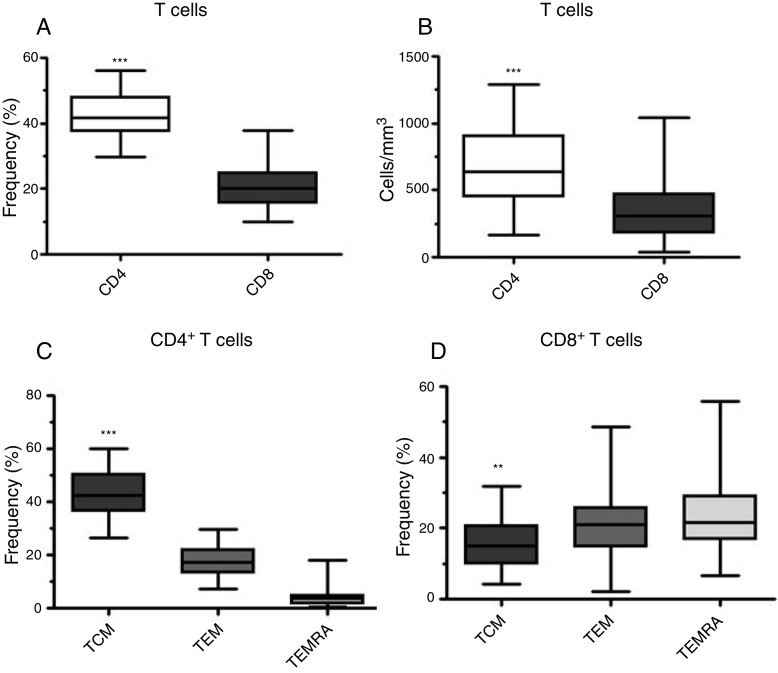

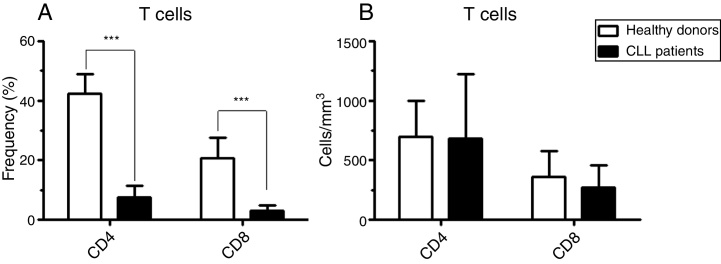

As expected, the frequency and the absolute number of CD4+ T cells were higher than those of CD8+ T cells in the Control Group (Figure 3). The T cell compartment was also characterized and the CD4 and CD8 subpopulations had different distributions according to memory T cell subsets. Central memory T cells (TCM) were predominant in the CD4+ T cell compartment, whereas TCM were fewer of the CD8+ T lymphocytes with TEM and TEMRA being distributed equally among CD8+ T lymphocytes (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Distribution profile of T cells in healthy donors. (A) Frequency and (B) absolute number of peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy individuals as assessed by flow cytometry. Frequency of memory (C) CD4+ and (D) CD8+ T cell subpopulations according to the CD45 and CD62L expression [central memory T cells (TCM – CD45RA− CD62L+), effector memory T cells (TEM – CD45RA− CD62L−) and terminal effector memory T cells (TEMRA – CD45RA+ CD62L−)]. The values were statistically significant with p-value < 0.001 (***) and p-value = 0.003 (**).

Characterization of T cell compartment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients

The analysis of the T cell compartment in CLL patients showed that, due to the increased numbers of neoplastic B lymphocytes in PB, the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were extremely low compared to healthy donors (Figure 4). Similar absolute numbers were observed in the PB of both patients and healthy controls (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Absolute number of CD4 and CD8 T cells is not changed in chronic lymphocyte leukemia (CLL) patients. (A) Frequency of peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in CLL patients compared to healthy donors. The values were statistically significant with p-value < 0.001 (***). (B) Absolute number of peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from CLL patients compared to the healthy donors.

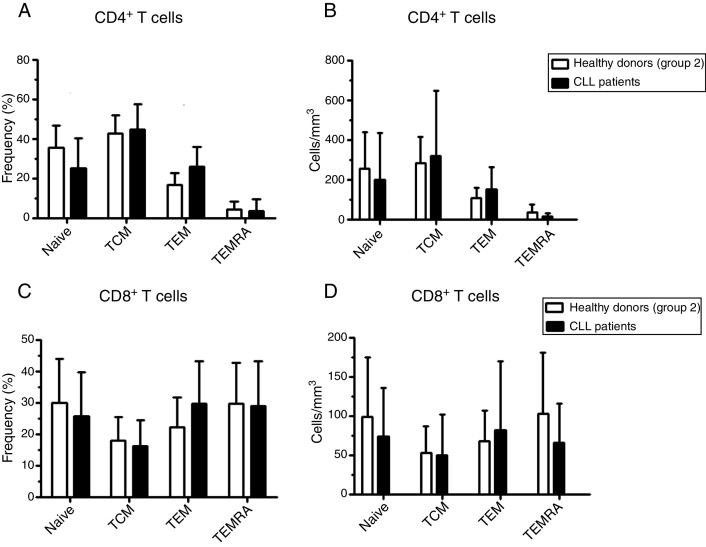

Distribution pattern of naïve and memory T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients

No differences in the frequency and the absolute number of naïve, TCM, TEM and TEMRA were observed in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations (Figure 5). However, ZAP-70 positive patients had significant differences in the frequencies of naïve and absolute number of TCM in the CD4+ T cell compartment. There was no difference in the frequency or the absolute number of CD8+ T cells in CLL patients compared to age-matched apparently healthy individuals (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Naïve and memory T cell distributions in chronic lymphocyte leukemia (CLL) patients. Peripheral blood T cell subsets in CLL patients and age-matched healthy donors (Group 2) were determined by flow cytometry. (A) Frequency and (B) absolute number of CD4+ naïve and memory T cells subsets. (C) Frequency and (D) absolute number of CD8+ naïve and memory T cells subsets. TCM: central memory T cells; TEM: effector memory T cells; TEMRA: terminal effector memory T cells.

Figure 6.

Naïve and memory CD4+ T cell distributions are related to the ZAP-70 expression in chronic lymphocyte leukemia (CLL) patients. (A–C) Frequency and (B–D) absolute number of CD4+ and CD8+ naïve and memory T cells subsets in CLL patients with and without ZAP-70 expression in comparison to age-matched healthy donors. Differences in the frequencies of naïve and absolute number of central memory T cells in the CD4+ T cell compartment were statistically significant with p-value < 0.001 and p-value = 0.008, respectively. TCM: central memory T cells; TEM: effector memory T cells; TEMRA: terminal effector memory T cells.

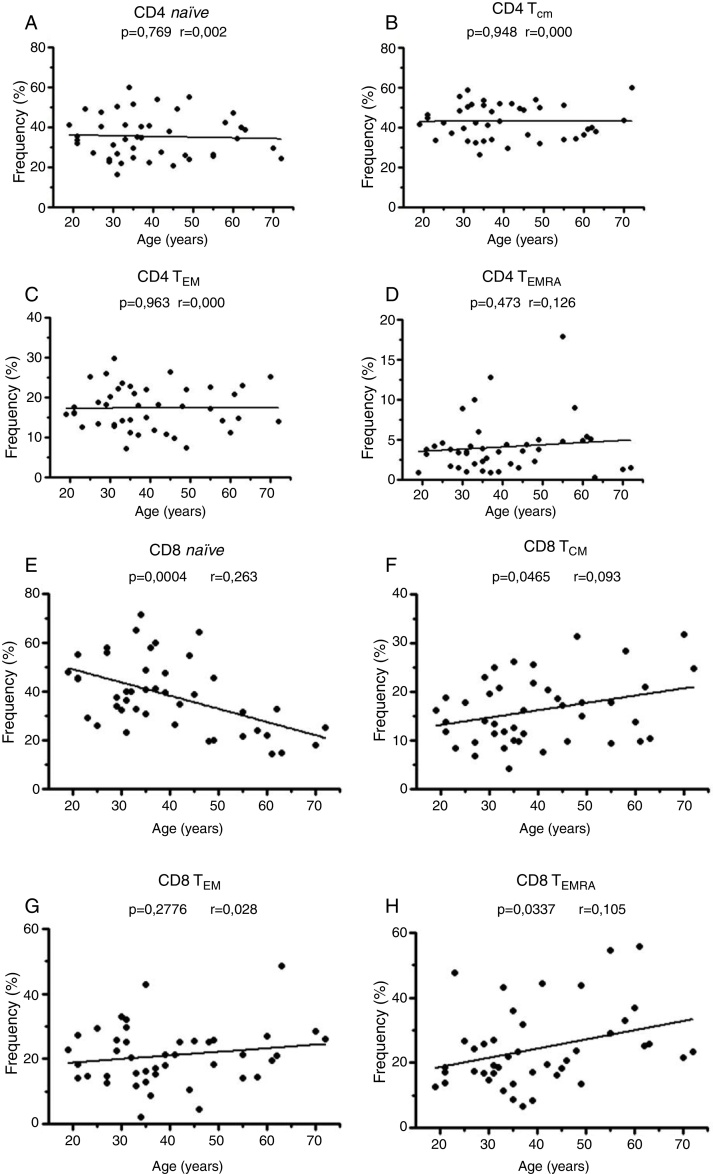

Age-dependent differences in the distribution of naïve and memory T cells

The literature suggests that events related to the age, such as homeostatic regulation, thymus involution and antigenic stimulation could affect the naïve and memory T cell distributions.6 Therefore, the next step was to rule out the possibility that the increase in TCM CD4+ cells was due to differences in the ages of the patients. On analyzing the healthy group (19–72 years old), no differences were observed in the naïve and memory CD4+ T cells with age (Figure 7), but in the CD8+ T cell compartment, the naïve T cells diminished and TCM and TEMRA cells increased with age (Figures 7E–H).

Figure 7.

Distribution of naïve and memory subtypes of CD8+ T cells, but not CD4+ T cells, is age dependent. Analysis of the frequency distribution of (A–D) CD4+ and (E–F) CD8+ naïve, central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM) and terminal effector memory T cells (TEMRA) in healthy donors (19–72 years old). Linear regression was used to evaluate the changes.

Discussion

The involvement of T cells in the pathophysiology of hematologic malignancies, especially in CLL, is widely discussed. The interaction of neoplastic B cells with their microenvironment, particularly CD4+ T lymphocytes and with extracellular components, could regulate the expansion, differentiation, and survival of neoplastic B cells, and possibly influence the T lymphocyte gene expression, function and phenotype.9, 10 This study showed that ZAP-70 positive patients presented increased TCM CD4+ T cells compared to ZAP-70 negative patients and to age-matched healthy donors (Figure 5).

Memory T cells represent a heterogeneous group of cells characterized by their phenotypic diversity, proliferative index versus effector function, and migratory capability to lymph nodes and/or to peripheral tissues. They are classified into three major groups: TCM, TEM, and TEMRA. Briefly, TCM are located in lymph nodes and have low effector function with a high proliferative index. On the other hand, TEM and TEMRA are characterized by high effector function in the liver, lung, and gut and with a low proliferative index. Together, these cells provide immediate protection in peripheral tissues and efficient secondary response in lymph nodes.15, 16, 17, 18

It is well established that the signaling and antigenic stimulation by B cell receptors (BCRs) is crucial for survival and growth of CLL cells, even though it is a disease with a low proliferative index.19 In this context, TCM CD4+ cells can migrate to the lymph nodes due to the expression of CD62L and CCR7, and interact with B cells by CD40L and CXCR5, that consequently could contribute to stronger BCR signaling, expansion and evolution of the disease.18 These data could support the finding that ZAP-70 positive CLL patients have increased TCM CD4+ T cells.

In addition to the modulation of BCR signaling, the cytokines produced by memory T cells, especially interleukin (IL)-4 and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), could promote increased survival of the CLL clone.20, 21 Recently, a study showed that ZAP-70 expression in CLL is associated with a reduction of naïve CD4+ T cells and increases in activation/differentiation of CD4+ T cells to a memory profile that expresses IL-4 or IL-10. In addition, these cytokines might favor the growth and survival of CLL cells.22

Furthermore, as neoplastic CLL B cells are inefficient as antigen presenting cells, the evidence that increased TCM CD4+ T cells could be a CLL mechanism is supported by the theory of the generation of memory T cells; a weak stimulation of naïve T cells during antigen presentation drives the differentiation of these cells into TCM cells.23, 24

To ratify that the changes detected in the CD4+ memory T cell compartment are a CLL intrinsic mechanism and not an age-dependent event, the frequency of these cells was evaluated in healthy donors stratified by age. Indeed, events related to age, such as homeostatic regulation, thymus involution and antigenic stimulation were observed,6 but this mechanism only affected the CD8+ T cell compartment (Figure 7). Therefore, our finding of increased TCM CD4 cells is a consistent result and directly associated with CLL, in particular, associated to ZAP-70 expression in this disease.

This study has limitations in evaluating the real association between the results with CLL prognosis, especially due to absent of experimental verification and correlation with other clinical and laboratory data. Still, we believe the increase in TCM CD4+ T cells might be a result of the crosstalk mechanism between CLL ZAP-70 positive B cells with normal CD4+ T cells, in which the neoplastic clone could obtain greater survival and expansion signals due to cytokines and costimulatory signals as described above. Interestingly, it is reported that murine models using animals deficient in B cells have impaired generation of CD4+ memory T cells.15, 25

These findings could be important to understand the pathophysiology, and consequently, they could help drive further investigations in the prognosis and treatment of CLL.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri A.S., Stein H. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2008. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inamdar K.V., Bueso-Ramos C.E. Pathology of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an update. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11(5):363–389. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puente X.S., Pinyol M., Quesada V., Conde L., Ordóñez G.R., Villamor N. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475(7354):101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riches J.C., Ramsay A.G., Gribben J.G. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an update on biology and treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13(5):379–385. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rai K.R., Sawitsky A., Cronkite E.P., Chanana A.D., Levy R.N., Pasternack B.S. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975;46(2):219–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binet J.L., Auquier A., Dighiero G., Chastang C., Piguet H., Goasguen J. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981;48(1):198–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810701)48:1<198::aid-cncr2820480131>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damle R.N., Wasil T., Fais F., Ghiotto F., Valetto A., Allen S.L. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94(6):1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespo M., Bosch F., Villamor N., Bellosillo B., Colomer D., Rozman M. ZAP-70 expression as a surrogate for immunoglobulin-variable-region mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(18):1764–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correia R.P., Matos E., Silva F.A., Bacal N.S., Campregher P.V., Hamerschlak N. Involvement of memory T-cells in the pathophysiology of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2014;36(1):60–64. doi: 10.5581/1516-8484.20140015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scrivener S., Goddard R.V., Kaminski E.R., Prentice A.G. Abnormal T-cell function in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(3):383–389. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000029993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tinhofer I., Weiss L., Gassner F., Rubenzer G., Holler C., Greil R. Difference in the relative distribution of CD4+ T-cell subsets in B-CLL with mutated and unmutated immunoglobulin (Ig) VH genes: implication for the course of disease. J Immunother. 2009;32(3):302–309. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318197b5e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofbauer J.P., Heyder C., Denk U., Kocher T., Holler C., Trapin D. Development of CLL in the TCL1 transgenic mouse model is associated with severe skewing of the T-cell compartment homologous to human CLL. Leukemia. 2011;25(9):1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Isolation of monuclear cells by one centrifugation, and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1968;97:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villamor N. ZAP-70 staining in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Curr Protoc Cytom. 2005;6:19. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0619s32. Chapter 6:Unit 6 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jameson S.C., Masopust D. Diversity in T cell memory: an embarrassment of riches. Immunity. 2009;31(6):859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pepper M., Jenkins M.K. Origins of CD4(+) effector and central memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(6):467–471. doi: 10.1038/ni.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sallusto F., Geginat J., Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallusto F., Lenig D., Förster R., Lipp M., Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401(6754):708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevenson F.K., Caligaris-Cappio F. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revelations from the B-cell receptor. Blood. 2004;103(12):4389–4395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buschle M., Campana D., Carding S.R., Richard C., Hoffbrand A.V., Brenner M.K. Interferon gamma inhibits apoptotic cell death in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Exp Med. 1993;177(1):213–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panayiotidis P., Ganeshaguru K., Jabbar S.A., Hoffbrand A.V. Interleukin-4 inhibits apoptotic cell death and loss of the bcl-2 protein in B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells in vitro. Br J Haematol. 1993;85(3):439–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monserrat J., Sánchez M.Á., de Paz R., Díaz D., Mur S., Reyes E. Distinctive patterns of naive/memory subset distribution and cytokine expression in CD4 T lymphocytes in ZAP-70 B-chronic lymphocytic patients. Cytom B Clin Cytom. 2014;86(1):32–43. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F. Understanding the generation and function of memory T cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17(3):326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dazzi F., D’Andrea E., Biasi G., De Silvestro G., Gaidano G., Schena M. Failure of B cells of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in presenting soluble and alloantigens. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;75(1):26–32. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitmire J.K., Asano M.S., Kaech S.M., Sarkar S., Hannum L.G., Shlomchik M.J. Requirement of B cells for generating CD4+ T cell memory. J Immunol. 2009;182(4):1868–1876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]