Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) results from triglyceride accumulation within the liver and some of them advances to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). It is important to note that in NAFLD development, hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) derives from excess carbohydrates and fats under a condition of excess energy through β-oxidation. As a main regulator for DNL, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (Srebp-1) forms complex with progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1). To investigate whether Pgrmc1 may have a notable effect on DNL via SREBP-1 activation, we generated Pgrmc1 knockout (KO) mice and fed a high fat diet for one month. High-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice showed a substantial increase in levels of hepatic TG accumulation, and they were predisposed to NAFLD when compared to WT mice. Loss of Pgrmc1 increased mature SREBP-1 protein level, suggesting that induction of hepatic steatosis in Pgrmc1 KO mice might be triggered by de novo lipogenesis. Moreover, Pgrmc1 KO mice were also more vulnerable to early stage of NASH, showing high levels of alanine aminotransferase, obesity-linked pro-inflammatory cytokines, and fibrosis markers. This is interesting because Pgrmc1 involves with the first step in regulating the hepatic de novo lipogenesis under an excess energy condition.

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a recently emerging problem mostly prevalent in western societies where obesity rates are high due to consumption of a high fat diet1. NAFLD typically results from hepatic triglyceride accumulation and accompanies steatosis and hepatitis2. When NAFLD becomes intensified, a small portion of NAFLD (30%) progresses to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Although less than half of NAFLD progresses to NASH, the progression can lead to serious liver injury such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). As mechanisms underlying the progression of NAFLD to NASH are not well characterized3–6, it is important to find a way to prevent NAFLD to reduce the risk of NAFLD progression to NASH.

Hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) is the metabolic pathway that enables accumulation of fatty acids in liver under condition of a high-carbohydrate and a high-fat diet7. It is also known that DNL levels are determined by the sterol regulatory element binding protein (Srebp). Srebp normally exists in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of the liver and consists of two members, Srebp-1 and Srebp-2. Srebp-1 regulates fatty acid metabolism and Srebp-2 regulates cholesterol synthesis by involving the pathway between mevalonate and lanosterol8,9. Srebp-1 is also one of the most significant transcriptional regulator for DNL in the liver, along with Lxr and Ppar, and they interact with each other in the DNL pathway10–14. SREBP-1 generally exists as an inactivated form and binds with Srebp cleavage-activated protein (SCAP), which forms complex with insulin induced gene 1 (INSIG-1) and progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1) in the ER of the liver15. After SCAP is activated by extracellular signaling, it dissociates with INSIG-1 protein and activates the SREBP-116. Then, SREBP-1 is transferred to the golgi complex and acts as the gene regulator for fatty acid synthesis and triglyceride synthesis17. Interestingly, PGRMC1 also plays a role in SREBP-1 activation18. As a novel surface cell receptor, PGRMC1 protein has been detected in various tissues such as the liver, lung, kidney, and brain19–21. Furthermore, PGRMC1 is a member of the PGRMC1/INSIG-1 complex, which is located in the ER of human and rodent liver. In addition to its role as a regulator of cancer cell survival, Pgrmc1 also affects cholesterol synthesis and steroidogenesis18,22–24. Moreover, a recent study revealed that PGRMC1 binds to INSIG-1 and subsequently regulates SCAP and SREBP-1 that are closely related to triglyceride synthesis25.

In the present study, we focused on the role of Pgrmc1 as a regulator of Srebp-1 in the hepatic DNL pathway. In our preliminary data, we have evidence that Pgrmc1 and Srebp-1 are associated by inverse-proportional expression. To investigate whether Pgrmc1 actually regulates lipogenesis, we generated Pgrmc1 knockout (KO) mice, fed them with a high fat diet, and assessed whether the loss of Pgrmc1 predisposes mice to NAFLD and results in the buildup of fatty acids via the DNL pathway.

Result

Generation of Pgrmc1 knockout mice

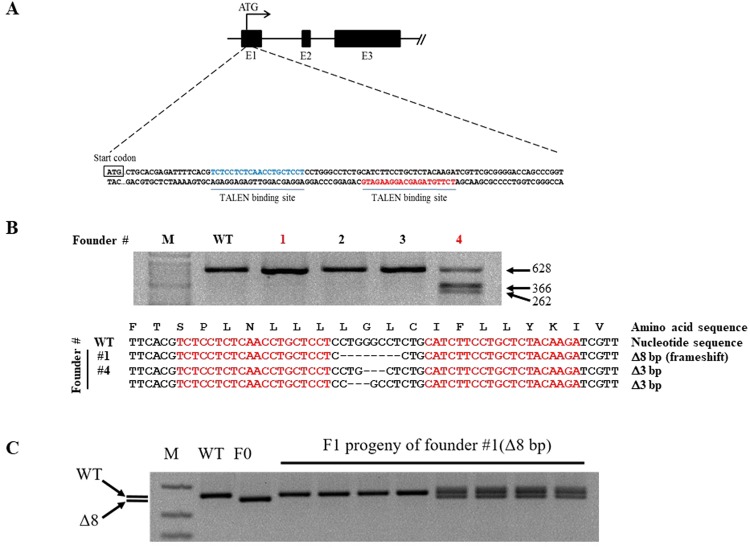

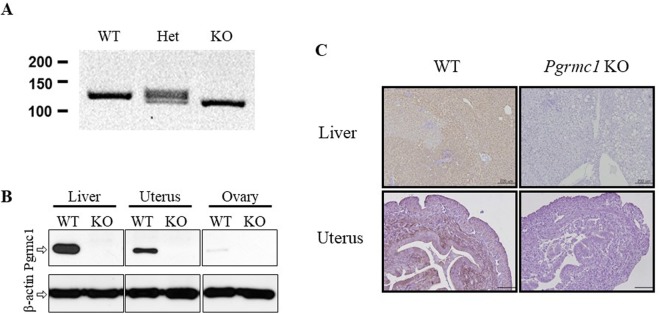

Considering that Pgrmc1 is highly expressed in liver, it can be speculated that Pgrmc1 is related to general liver function. To investigate role of Pgrmc1, we generated the knockout mice using transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN). An illustration of genome targeting and editing strategy in exon 1 was as shown in Fig. 1A. Whether Pgrmc1 allele was ablated was investigated using T7 endonuclease (T7E1) assay and genomic DNA sequencing was performed to elucidate 8 base pair (bp) deletion with a frameshift in founder #1 (Fig. 1B). By crossing with wild-type, the progeny of founder #1 showed wild-type and heterozygote band exclusively, indicating that germline transmission was successful (Fig. 1C). Even though TALEN has successfully deleted on-target sites at exon 1, potential off-target sites of Pgrmc1-TALEN were analyzed. Sequences of expected off-target sites are as listed in Table 1. With 3–5 base pairs of mismatch, chromosomes 1, 5, 6, 12, and 17 were examined by T7E1 assay and genotyping were conducted. Compared with wild-type band, none of the chromosomes were off-targeted (Fig. S1). The absence of Pgrmc1 was confirmed by PCR genotyping, western blot analysis, and immunohistochemistry in liver (Fig. 2A–C). Wild-type allele was detected as 128 bp and mutant allele was 120 bp in size (Fig. 2A). PGRMC1 protein was detected in protein extracts from the tissues of wild-type, while this band was absent from those of Pgrmc1 KO mice, which confirms the ablation of the PGRMC1 protein (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemistry of the liver and uterus also demonstrated that PGRMC1 protein was completely depleted in Pgrmc1 KO mice (Fig. 2C). To sum it up, expression tests confirmed that functional PGRMC1 was completely depleted in knockout mice.

Figure 1.

Gene targeting and generation of TALEN-mediated Pgrmc1 mutant mice. (A) Target region of Pgrmc1-TALEN in mouse Pgrmc1 locus. (B) T7E1-based mutation detection assays and sequencing analysis. The numbers indicated wild type (WT, in black) and mutant (in red) mice. Colored sequences of Pgrmc1 indicate TALEN binding sites. “-” denoted deleted nucleotides. M, a molecular size marker. (C) Pgrmc1 mutant founder #1 was crossed to WT mouse and the genotypes of the pups were determined by PCR analysis.

Table 1.

Potential off-target sites of Pgrmc1-TALEN.

| Locus | Left TALEN binding site | Mismatch # | Right TALEN binding site | Mismatch # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pgrmc1 | TCTCCTCTCAACCTGCTCCT | TCTTGTAGAGCAGGAAGATG | ||

| Chr1:170565021–170565072 | TCTCCTCTtcACCTcCTCCc | 4 | TCTTGaAAAAatAAAAAAcA | 4 |

| Chr17:85818163–85818214 | TCTCtTCTCAcCCTcCTCCc | 4 | TCcTGTccAGatGGAAAATG | 5 |

| Chr12:60494489–60494540 | TacCCTCTCcACCTACTCCT | 3 | TtTgGTGGAcaAGGAAAATG | 4 |

| Chr6:60182750–60182801 | TCTCCTaTCcACCcACTCCc | 4 | TCcaGTAcAGgAAAAAGccA | 6 |

| Chr5:138161764–138161815 | TCcCCTCTCAcaCTGCTCCT | 3 | TaTcATtGAcaAAGAAtATt | 7 |

Figure 2.

No detectable PGRMC1 protein in Pgrmc1 knockout mice. (A) Genomic DNA showing PCR amplification of wild-type (WT), Pgrmc1 heterozygote (Het) and homozygote (KO) alleles. Pgrmc1 WT band is shown at 128 bp, whereas mutant band is at 120 bp. (B) Western blot showing ablation of the PGRMC1 protein. (C) Immunohistochemistry from PGRMC1 WT and Pgrmc1 knockout mice. (Liver; 8-week old male, uterus; ovariectomized and P4 injected mice. Scale bar, 200 µm for liver and 100 µm for uterus).

Hepatic TG accumulation significantly increases in Pgrmc1 KO mice

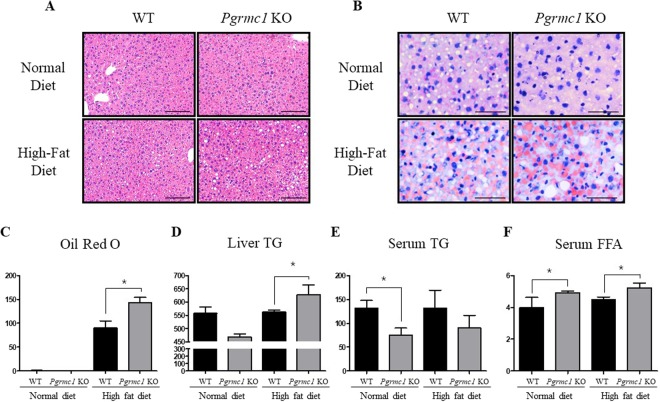

Control WT and Pgrmc1 KO groups were fed a normal diet and experimental WT and Pgrmc1 KO groups were fed a high fat diet for 1 month. After necropsy, high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice showed increased lipid accumulation within the liver when compared to high-fat-fed WT mice. Lipid droplets observed in H&E stained liver sections were remarkably larger in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice when compared to that of WT mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, on Oil-Red-O staining, lipid droplets were stained with red orange color and its quantification showed an increase (P < 0.05, 1.43 fold) in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice (Fig. 3B,C). Similarly, after extracting lipids from the liver, triglyceride levels were measured with a commercial kit mentioned above and it showed significantly increased (P < 0.05, 1.12 fold) in the liver of high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice when compared to high-fat-fed WT mice (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that numerous lipid droplets in Oil-Red-O staining were triglycerides, which accumulated within the liver of high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice. On the other hand, there was a slight decrease (P = 0.14, 68.5%) in serum TG levels in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice when compared to high-fat-fed WT mice and Pgrmc1 KO mice fed a normal diet also showed a decrease (P < 0.05, 56.8%) in serum TG levels when compared to WT mice fed a normal diet (Fig. 3E). Meanwhile, serum free fatty acid (FFA) levels in high-fat fed Pgrmc1 KO mice significantly increased (P < 0.05, 1.16 fold) than those of high-fat-fed WT mice (Fig. 3F). Similarly, Pgrmc1 KO mice fed a normal diet showed significantly increased (P < 0.05, 1.18 fold) serum FFA levels when compared to WT mice fed a normal diet (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Loss of Pgrmc1 increases hepatic TG accumulation. Normal diet and high fat diet were fed for 1 month to WT and Pgrmc1 KO mice. (A) Lipid droplets are characterized in H&E staining (Scale bar, 50 µm). (B) Oil Red O staining presents TG accumulation in hepatocytes (Scale bar, 25 µm). (C) Quantification of Oil Red O was analyzed by Image J as setting red cells for positive standard. (D) Total lipid from liver was extracted by folch method and level of TG was measured by colorimetric method in 550 nm. (E) Level of TG (triglycerides) in plasma showed inverse proportional level compared to liver TG. (F) Level of FFA in plasma was increased in Pgrmc1 KO mice. Values represent means ± SD. *P < 0.05. Number of mice used in experiment is at least 3 for each group.

TG accumulation in Pgrmc1 KO liver links to increase of Srebp-1 level

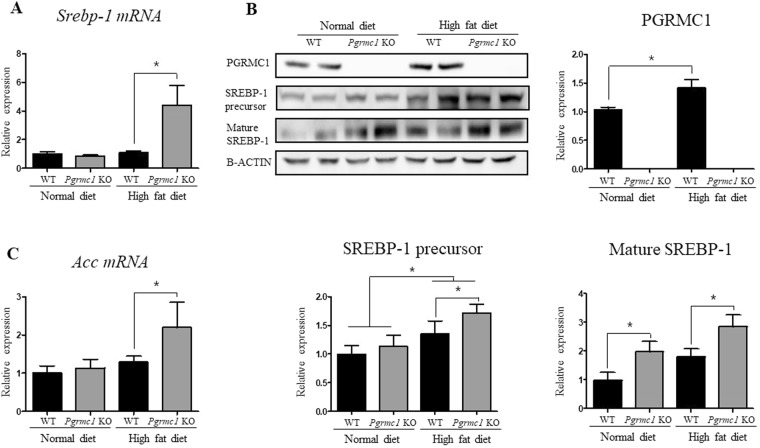

First, we assessed transcriptional regulator genes involved in fatty acid synthesis, such as Pparγ, Lxr, and Srebp-1. As a result, Srebp-1 mRNA level significantly increased (P < 0.05, 4.02 fold) in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice when compared to high-fat-fed WT mice (Fig. 4A). Although Pparγ and Lxr mRNA levels increased in high fat diet, the differences between WT mice and Pgrmc1 KO mice were not observed (Fig. S2A). Meanwhile, protein levels of SREBP-1 precursor were increased in WT and Pgrmc1 KO mice fed a high fat diet (P < 0.05, 3.1 fold and 2.8 fold) than normal diet, but the differences between WT mice and Pgrmc1 KO mice were not observed (Fig. 4B). Rather, protein levels of mature SREBP-1 were significantly increased in Pgrmc1 KO mice fed a normal diet (2.01 fold) and high fat diet (1.53 fold), when compared to those of WT mice (P < 0.05, Fig. 4B). These results suggest that level of active SREBP-1 protein is induced by loss of PGRMC1. Accordingly, among the genes directly controlled by SREBP-1, Acc mRNA levels was increased (P < 0.05, 1.7 fold) in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice when compared to high-fat fed WT mice (Fig. 4C). In addition, fatty acid esterification enzymes, Agpat1 (1.94 fold) and Mogat1 (2.99 fold), were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in mRNA levels of high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice than high-fat-fed WT mice (Fig. S2B). These results suggest that TG accumulation was promoted under condition of increase of Srebp-1 level, as a phenotype of Pgrmc1 KO mice.

Figure 4.

Loss of Pgrmc1 increases level of Srebp-1. (A) Substantially increased mRNA level of Srebp-1 in liver of high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice. (B) Protein level of PGRMC1 was increased after high fat diet. Increased protein level of SREBP-1 precursor in livers of high-fat-fed group, and comparatively more increased protein level of mature SREBP-1 in liver of high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice. (C) Increased mRNA level of Acc in liver of high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice. Rplp0 mRNA was used as an internal control in real time PCR. Beta actin was used as an internal control in western blot. Values represent means ± SD of at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05. Number of mice used in experiment is at least 3 for each group.

Interestingly, both mRNA (2.09 folds, Fig. S3) and protein (1.43 fold, Fig. 4B) level of Pgrmc1 were increased (P < 0.05) in high-fat-fed WT mice than WT mice fed a normal diet, suggesting that Pgrmc1 can also be used as potential biomarker in steatosis. Meanwhile, Insig-1, which forms complex with Pgrmc1, also significantly showed increase (P < 0.05, 3.74 and 2.11 fold) in mRNA level in Pgrmc1 KO mice, when compared to WT mice in normal diet or high fat diet (Fig. S3). Likewise, Scap, which forms with Pgrmc1 and Insig-1, increased in mRNA level (1.29 fold, P = 0.33) in Pgrmc1 KO mice, but showed no significance (Fig. S3).

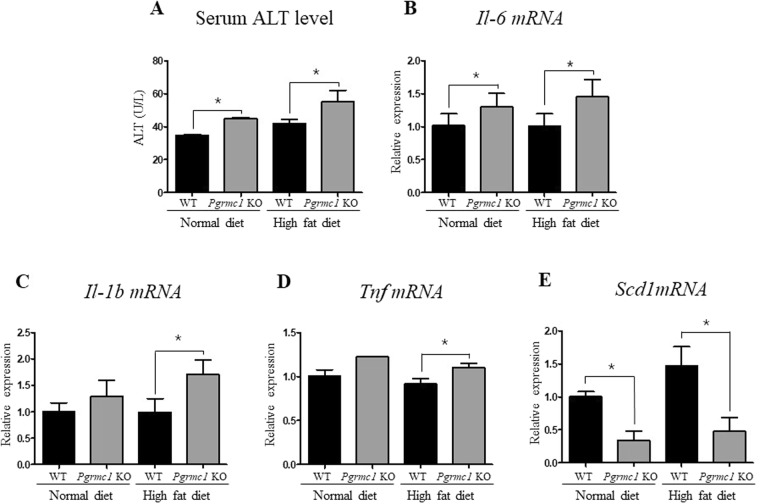

Loss of Pgrmc1 promotes steatosis-induced NASH

As a hepatic injury marker, ALT levels were measured in serum. As a result, normal diet (1.29 fold) and high-fat-fed (1.26 fold) Pgrmc1 KO mice showed significantly (P < 0.05) higher levels of ALT than those of WT mice fed with a normal diet and high fat diet (Fig. 5A). Moreover, to assess the level of genes followed by hepatic inflammation, we analyzed Tnf (1.2 fold), Il-6 (1.32 fold), and Il-1β (1.72 fold) mRNA levels and observed significant (P < 0.05) increases in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice than those of high-fat-fed WT mice (Fig. 5B–D). In addition, we monitored macrophage infiltration in liver using a F4/80 antibody, macrophage marker, F4/80. Although liver has resident macrophage like Kupffer cells, the increased macrophage (F4/80-positive) infiltration in Pgrmc1 KO mice suggests possibility for inflammation of NASH (Fig. S4). This result also suggests that the macrophage infiltrate the liver in response to NAFLD challenge. Likewise, the mRNA level of Scd1, which is protective to lipotoxicity, showed significant decrease (P < 0.05) in Pgrmc1 KO mice fed a normal diet (33.8%) and high fat diet (32.5%) when compared to those of WT mice (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Pgrmc1 KO mice possesses more susceptible condition for NASH with inflammation. (A) ALT levels in plasma indicates hepatic injury relates to inflammation. (B–D) Increased mRNA level of pro-inflammatory cytokines in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice. (E) Decreased mRNA level of Scd1 gene in high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice. Rplp0 mRNA was used as an internal control in real time PCR. Values represent means ± SD of at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05. Number of mice used in experiment is at least 3 for each group.

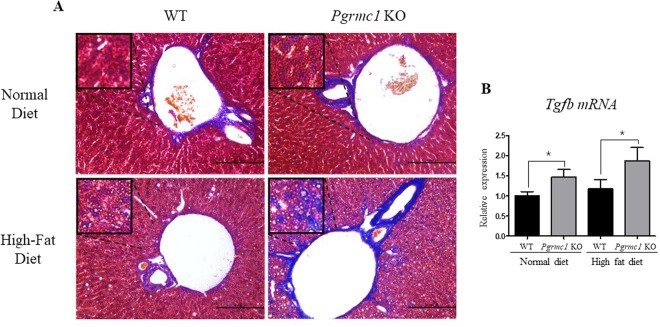

To further evaluate NASH under condition of high-fat diets, we monitored the hepatic fibrosis using Masson’s trichrome staining. As expected, high-fat-fed Pgrmc1 KO mice showed significantly higher ratio of blue-stained fibroblasts compared to those within WT mice fed with a normal diet and high fat diet, and the fibroblasts was mainly confined around the central vein of lobules (Fig. 6A). As another fibrosis marker, the level of Tgf-β mRNA also showed significant (P < 0.05) increase in both of normal diet-fed (1.46 fold) and high-fat-fed (1.58 fold) Pgrmc1 KO mice than those of WT mice (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that Pgrmc1 KO mice are genetically more prone to NAFLD-induced liver inflammation or NASH.

Figure 6.

Pgrmc1 KO mice possesses more susceptible condition for NASH with fibrosis. (A) Masson’s trichrome staining indicates fibroblasts produced by steatosis (Scale bar, 100 µm). (B) Increased mRNA level of fibrosis marker, Tgf-b, in livers of Pgrmc1 KO mice. Rplp0 mRNA was used as an internal control in real time PCR. Values represent means ± SD of at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05. Number of mice used in experiment is at least 3 for each group.

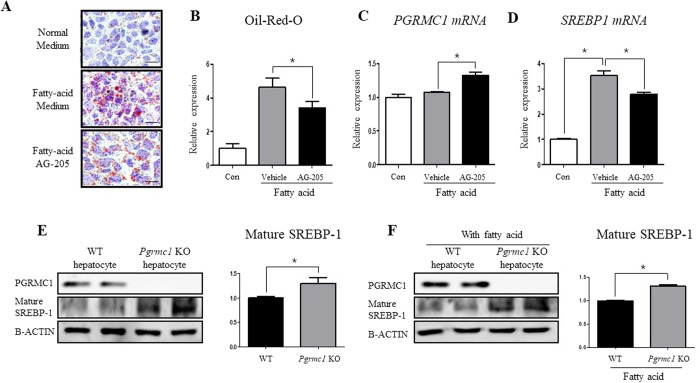

Liver-specific regulation of PGRMC1 controls level of SREBP-1 and steatosis

For inducing lipogenesis, palmitic acid (330 μM) and oleic acid (660 μM) were treated for 48 hours and AG-205 was co-incubated in Hep3B cells. As a result, Oil-Red-O stained areas were significantly decreased (P < 0.05, 74.1%) in fatty acid + AG-205-treated group when compared to the fatty acid treated group, suggesting that lipid storage has been significantly reduced (Fig. 7A,B). Moreover, after treating fatty acids for 4 hours with pre-incubation of AG-205 for 12 hours, PGRMC1 mRNA level increased (P < 0.05, 1.23 fold) in fatty acid + AG-205 group when compared to fatty acid group (Fig. 7C). On the one hand, SREBP-1 mRNA level was inversely proportional to PGRMC1 mRNA level, showing decreased level (P < 0.05, 75.8%) in the fatty acid + AG-205 group when compared to AG-205 group (Fig. 7D). These results show that up-regulation of PGRMC1 down-regulates lipid accumulation in hepatocyte with decreased level of SREBP-1.

Figure 7.

Liver-specific regulation of Pgrmc1 controls hepatic fat accumulation through SREBP-1. (A,B) Palmitic acid (330 µM) and oleic acid (660 µM) were incubated for 48 hrs with high glucose medium. Fatty acid substantially increased Oil Red O stained area and AG-205 ameliorated fat accumulation in hepatocyte (Scale bar, 10 µm). (C,D) Fatty acids were incubated in same concentration as above for 4 hrs after pre-incubation of AG-205 for 12 hrs. PGRMC1 mRNA level was increased after AG-205 treatment and SREBP-1 mRNA level was inversely changed to PGRMC1 mRNA level. (E,F) Cells were isolated from mice and maintained in high glucose medium for one day. Fatty acids (Palmitic acid; 330 µM, Oleic acid 660 µM) were treated for 24 hrs. Levels of mature SREBP-1 protein were increased in loss of Pgrmc1. Rplp0 mRNA was used as an internal control in real time PCR. Beta actin was used as an internal control in western blot. Values represent means ± SD of at least 3 experiments. *P < 0.05.

To investigate whether the lipogenic effect in the loss of Pgrmc1 is liver-specific, we therefore introduced primary hepatocyte culture system and observed significantly increased (P < 0.05, 1.3 fold) level of mature SREBP-1 protein in Pgrmc1 KO hepatocytes when compared to WT hepatocytes (Fig. 7E). Likewise, level of mature SREBP-1 protein also significantly increased (P < 0.05, 1.31 fold) in fatty acid treated Pgrmc1 KO hepatocytes when compared to that of WT hepatocytes (Fig. 7F). The phenotypic characteristic of Pgrmc1 was also confirmed by siRNA transfection with significantly increased (P < 0.05, 1.36 fold) level of mature SREBP-1 protein in PGRMC1 knockdown Hep3B cell when compared to control cell (P < 0.05, 65%, Fig. S7).

Discussion

The fatty liver is predisposed to injuries involving oxidant stress, which subsequently leads to inflammation26. NASH, the typical feature of NAFLD, occurs during accumulation of fatty acids following hepatic de novo lipogenesis or plasma lipid transport from extrahepatic tissues27,28. In addition, numerous studies reported that steatohepatitis increased the risk of HCC28,29. Interestingly, the present study shows that Pgrmc1 KO mice are vulnerable to NAFLD triggered by a high-fat diet when compared to WT mice. Moreover, Pgrmc1 KO mice were predisposed to liver inflammation and fibrosis; therefore, loss of Pgrmc1 can increase the risk of hepatic diseases such as NAFLD and NASH under high-fat diets typical of western societies.

After mice were fed a high-fat diet, Pgrmc1 KO mice showed significant increases in hepatic TG accumulation. Pgrmc1 KO mice also showed significant increases in plasma FFA, while plasma TG revealed a corresponding reduction in levels. In a recent study, patients with NAFLD had accumulation of TG within the liver mainly from hepatic de novo lipogenesis rather than from plasma fatty acids30. Thus, we focused on hepatic lipogenesis to investigate the mechanism of increased hepatic steatosis in the loss of Pgrmc1.

To assess the transcription regulating gene involved in fatty acid synthesis of lipogenesis, we observed the increase of Srebp-1 level following the loss of Pgrmc1. When SREBP-1 is the primary regulator of fatty acid synthesis and TG storage within the liver31, it was found to be inactive in its precursor form under non-high fat conditions. After being cleaved from the SCAP/SREBP-1 complex through signaling, SREBP-1 becomes mature and plays a role as a transcriptional factor for triggering hepatic de novo lipogenesis32. The signal for cleavage of the SCAP/SREBP-1 complex is transmitted from the PGRMC1/INSIG-1 complex, implying that PGRMC1- is closely involved with SREBP-1 function. More recently, it was reported that SCAP/SREBP-1 expression increases under a condition of low PGRMC1/INSIG-1 expression25. Likewise, the present study shows significantly increased levels of Srebp-1 mRNA and mature SREBP-1 protein in the absence of Pgrmc1. Since induction of SREBP-1 has been linked to the accumulation of TG within the liver through de novo lipogenesis33, our data support the claim that hepatic TG accumulates within the Pgrmc1 KO liver following an increase of Srebp-1 levels.

In addition, our results provide evidence that Pgrmc1 has a novel function as an inhibitory factor of hepatic de novo lipogenesis. As a Srebp-1-dependent protein, ACC plays a crucial role in lipogenesis and fatty acid synthesis34,35 as its protein product is responsible for the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA. Furthermore, reduction of its inactive form was also used as an indicator of lipogenesis36. In this study, we observed an increased level of Acc in the absence of Pgrmc1, with increased SREBP-1 level. Moreover, we observed increased transcript level of fatty acid esterification enzymes, Agpat and Mogat, which may promote the growth of lipid droplets and TG accumulation in the absence of Pgrmc137,38. These data, therefore, suggest that Pgrmc1 KO mice are predisposed to lipogenesis in the liver. On the other hand, an increased level of fatty acid metabolism genes was observed after the loss of Pgrmc1 (Figs S5 and S6), suggesting that TG accumulation in Pgrmc1 KO liver was not induced by impaired fatty acid degradation.

Next, we observed an unexpected reduction in transcripts related to lipogenesis (Scd1 mRNA) in the absence of Pgrmc1 in both groups fed a normal diet and a high fat diet. Pgrmc1 KO mice have a phenotype showing low levels of Scd1 transcript, Scd1 being the primary regulator in fatty acid synthesis, converting saturated fatty acids to monounsaturated fatty acids and preventing lipotoxicity37–39. As the Scd1 gene plays a key role in preventing steatohepatitis, Pgrmc1 deficiency could lead to a NASH-susceptible state, like that of Scd1 KO mice38. Therefore, our data suggest that Pgrmc1 KO mice are genetically more vulnerable to lipotoxicity acquired by hepatic steatosis. Meanwhile, plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is a well-known marker for inflammation as it is located inside the liver cell and increases after hepatocyte damage. Lipotoxicity due to low Scd1 levels after the loss of Pgrmc1 should be linked to plasma ALT levels, and Pgrmc1 KO mice showed enhanced levels of ALT over WT mice both in a normal diet and a high-fat diet. Though NASH is not always concomitant with ALT40, we supported our claim with the increased level of obesity-linked pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and TNF41. These cytokines are well known mediators for inflammation or HCC induced by hepatic steatosis, because IL-6 is involved in low-grade chronic inflammation and poor prognosis of NAFLD42,43. In addition, we observed an increase of macrophage infiltration in the absence of Pgrmc1, suggesting a high possibility for inflammation triggered by NASH. Likewise, considerable increases of fibroblasts and Tgfb transcript level also suggest susceptibility to fibrosis induced by steatosis in the loss of Pgrmc144,45. Therefore, based on our results, Pgrmc1 KO mice might have high risk factors for NASH including liver inflammation and fibrosis, and HCC triggered by a high-fat diet.

To gain insight into the correlation between Pgrmc1 and hepatic lipogenesis, we introduced AG-205 into Hep3B cells in a medium supplemented with fatty acids. Similar to the in vivo data, when PGRMC1 mRNA level increased significantly after treatment with AG-205, fat storage significantly decreased in the PGRMC1-induced condition. In addition, PGRMC1 directly regulated the mRNA level of SREBP-1, suggesting that lipogenesis could also be controlled by following PGRMC1 promotion. Meanwhile, we further confirmed that lipogenic control of Pgrmc1 is liver-specific by introducing a primary hepatocyte culture, observing increased levels of mature SREBP-1 in Pgrmc1 KO hepatocytes. Likewise, we also decreased the level of PGRMC1 and observed an increased level of mature SREBP-1 in siRNA transfection.

In summary, our study suggests that the loss of Pgrmc1 within the liver not only increases cellular lipid levels, but also enhances the risk for steatohepatitis. These findings are particularly interesting for cancer cell metabolism in light of reports that regard Pgrmc1 as a clinical parameter for hepatocellular carcinoma46 and find that Pgrmc1 is strongly expressed in different kinds of cancer47,48. We also suggest that the loss of Pgrmc1 might enhance sensitivity for lipotoxicity in animals and possibly humans even under a low-lipid diet.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibody for Beta-actin (sc-130656) was purchased from Santa Cruz biotechnology (Santacruz, CA, USA). Rabbit monoclonal antibody specific for Pgrmc1 (CST, #13856) was purchased from CST. Mouse monoclonal antibody specific for Srebp1 (sc-13551) was purchased from Santacruz.

Animals

Pgrmc1 KO mice were generated by TALEN method. Pgrmc1 specific TALEN plasmids were obtained from ToolGen, Inc. (South Korea). General methods for TALEN mediated KO mice production were previously described49. Briefly, Single dose of Pgrmc1 TALEN mRNA (50 ng/ul) was injected into the cytoplasm of C57BL/6 N mouse eggs with well recognized pronuclei and transferred into the oviducts of pseudo-pregnant foster mothers. To evaluate non-specific effects of TALEN, potential off-target sites were predicted as previously described50 (Table 1), and T7E1 assays were performed using genomic DNA samples from F0 mutant mice. For routine PCR genotyping of F1 progeny from selected F0 founder mice, the following primer pair was designed to amplify a 128 bp PCR product from wild-type mice and TALEN-induced mutant alleles: 5′-GGCTGCTGCACGAGATTTTC-3′ and 5′-GGTGGTTCGTCGTCGTCGTTG-3′ (Fig. 1).

C57BL/6N WT and Pgrmc1 KO female mice were housed in the pathogen-free facility at Chungnam National University and fed with standard chow and high fat diet with water provided ad libitum. All mouse experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the Chungnam National University Animal Care Committee (CNU-00606). Sacrifice was performed by CO2 asphyxiation. Number of mice used for experiment was 3 for each normal diet groups and 4 for each high fat diet groups.

Plasma TG, FFA and ALT level

All serums were diluted by 1/5 fold with PBS. Plasma TG and ALT level were measured with FUJI DRI-CHEM SLIDE (TG-1650, ALT-3250) by DRI-CHEM4000 (Fuji Film). Plasma FFA was measured with commercial kit (BM-FFA100) obtained from Biomax (Seoul).

Liver TG level

Lipid extraction from liver was done with Folch method. 0.2 g of liver tissue was homogenized with beads and 0.9% NaCl solution. After mixing with chloroform and methanol (1:2), samples were let stand for 30 minutes on room temperature. Additional mix with chloroform and distilled water, lower phase was separated after centrifuged on 3,000 rpm, 20 mins. Steps after homogenization were repeated for 3 times. Samples were filtrated with filter paper and the flow-through was heated in water bath. By this step, chloroform phase was evaporated. After complete dry in dry oven, it was dissolved in chloroform and 2-propanol. Samples were stored in room temperature. TG level was analyzed with TG measurement solution (AM157S-K, Asan-Set) in 550 nm spectrophotometer

RNA Isolation, reverse transcription, and qRT-PCR

Total RNA extracts from mouse liver or Hep3B cells were prepared using the TRIzol® Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with 1.5 µg of total RNA and Reverse transcriptase kit (SG-cDNAS100, Smartgene, United Kingdom) following manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR (real-time PCR) was carried out using specific primers (Table 2), Excel Taq Q-PCR Master Mix (SG-SYBR-500, Smartgene) and Stratagene Mx3000p (Agilent) equipped with a 96-well optical reaction plate. Negative controls, containing water instead of sample cDNA, were used in each plate. All experiments were run in triplicate and mRNA values were calculated based on the cycle threshold and monitored for melting curve

Table 2.

Primers used for real-time or conventional PCR.

| Gene name | Upper primer (5′-3′) | Lower primer (5′-3′) | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rplp0 | GCA GCA GAT CCG CAT GTC GCT CCG | GAG CTG GCA CAG TGA CCT CAC ACG G | Mouse |

| Lxr | CTC AAT GCC TGA TGT TTC TCC T | TCC AAC CCT ATC CCT AAA GCA A | Mouse |

| Pparγ | GAC CAC TCG CAT TCC TTT GAC | ATG CAG GTT CTA CTT TGA TCG C | Mouse |

| Srebp1 | GCC CGG ACA CAC CAG CTC | TGC CCA GGA GCC GAC AGG | Mouse |

| Scd1 | CTG TTC GTT AGC ACC TTC TTG | CAG AGT AGT CGA AGG GGA AG | Mouse |

| Tnf | CCT GTA GCC CAC GTC GTA G | GGG AGT AGA CAA GGT ACA ACC C | Mouse |

| Il-6 | CTG CAA GAG ACT TCC ATC CAG | AGT GGT ATA GAC AGG TCT GTT GG | Mouse |

| Il-1β | GAA ATG CCA CCT TTT GAC AGT G | CTG GAT GCT CTC ATC AGG ACA | Mouse |

| Acc | TGT GGG CTG GCT GGG GTC | CTG CCA CTC CAG GGA AGA G | Mouse |

| Acly | CAT CGG CGT TGC GTT TGT GG | GCC CAT ACT CCT TCC TAG CA | Mouse |

| Agpat1 | TAA GAT GGC CTT CTA CAA CGG C | CCA TAC AGG TAT TTG ACG TGG AG | Mouse |

| Mogat1 | TGG TGC CAG TTT GGT TCC AG | TGC TCT GAG GTC GGG TTC A | Mouse |

| Tgfb | GAC GTC ACT GGA GTT GTA CG | GGT TCA TGT CAT GGA TGG TG | Mouse |

| Insig-1 | CAC GAC CAC GTC TGG AAC TAT | TGA GAA GAG CAC TAG GCT CCG | Mouse |

| Scap | TGG AGC TTT TGA GAC TCA GGA | TCG ATT AAG CAG GTG AGG TCG | Mouse |

| Cd36 | ATG GGC TGT GAT CGG AAC TG | GTC TTC CCA ATA AGC ATG TCT CC | Mouse |

| Pparα | GCG TTT CCT GAG ACC CTC G | GGC TCT CTG TGT CCA CCA TG | Mouse |

| Mcad | AGG TTT CAA GAT CGC AAT GG | CTC CTT GGT GCT CCA CTA GC | Mouse |

| Cpt2 | CAG CAC AGC ATC GTA CCC A | TCC CAA TGC CGT TCT CAA AAT | Mouse |

| Acox1 | TTG GAA ACC ACT GCC ACA TA | AGG CAT GTA ACC CGT AGC AC | Mouse |

| Hsl | TCC CTC AGT ATC TAG GCC AGA | GGC TCA TTT GGG AGA CTT TGT TT | Mouse |

| Apo B | TTG GCA AAC TGC ATA GCA TCC | TCA AAT TGG GAC TCT CCT TTA GC | Mouse |

| Apo E | CTG ACA GGA TGC CTA GCC G | CGC AGG TAA TCC CAG AAG C | Mouse |

| Ldlr | AGT GGC CCC GAA TCA TTG AC | CTA ACT AAA CAC CAG ACA GAG GC | Mouse |

| Vldlr | GGC AGC AGG CAA TCG AAT G | GGG CTC GTC ACT CCA GTC T | Mouse |

| Pgrmc1 | GGC AAG GTG TTC GAC GTG A | GTC CAG GCA AAA TGT GGC AA | Mouse |

| Fabp4 | CCG CAG ACG ACA GGA AGG T | AGG GCC CCG CCA TCT | Mouse |

| Fatp2 | GCT GAC ATC GTG GGA CTG GT | TTC GAC CCT CAT GAC CTG GC | Mouse |

| Fatp5 | ACC ACT GGA CTC CCA AAG CC | AGG ACA GCA CGT TGC TCA CT | Mouse |

| Fabp5 | TCT TAA GGA TCT CGA AGG GAA | CTT CCT AAG AGC CAG TCC TAC T | Mouse |

| PGRMC1 | AAA GGC CGC AAA TTC TAC GG | CCC AGT CAC TCA GAG TCT CCT | Human |

| SREBP1 | CGG AAC CAT CTT GGC AAC AGT | CGC TTC TCA ATG GCG TTG T | Human |

Western blotting

Total liver and hep3B cell samples were homogenized by protein lysis buffer [T-PER (#78510, Thermo)] containing proteinase inhibitor (PMSF). Homogenized samples were quantified by Bradford assay with PRO-Measure solution (Intron, #21011) and proceeded to protein electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) after 5 min of boiling in 100 °C. Gels were blotted by wet transfer with Bio-Rad Power Pac in 350 mA. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour in Skim milk and incubated with a primary antibody (see above) for overnight, 4 °C. After 3 times of washing with PBS-T or TBS-T, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (AE-1475 goat anti-rabbit, BS-0296G-HRP goat anti-mouse, Bioss) for 4 hours diluted with 1:5000 in skim milk or BSA. Results were detected with ECL solution (XLS025-0000, Cyanagen) and Chemi Doc (Fusion Solo, Vilber Lourmat).

Histological analyses

For hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining, paraffin embedded tissue were cut by 4 μm and attached to silane coated slide. With serial hydration step in xylene, ethanol and distilled water, hematoxylin and eosin were stained. Region of interest was observed by light microscope. For Masson’s trichrome staining, slides were proceeded by manufacturer’s protocol (BioGnost, MST-100T).

For Oil-Red-O, frozen tissue were cut by 7 μM after embedded with OCT compound and attached to silane coated slide. After drying 10 mins in RT, slides were fixed with formalin for 20 mins and washed with running tap water for 10 mins. Slides were proceeded to rinse step with 60% isopropanol and stained with Oil Red O working solution (3 g/l) for 15 mins. After washing with 60% isopropanol, slides were stained with hematoxylin for 30 secs and rinsed with distilled water. Region of interest was observed by light microscope after mounted in aqueous mountant.

For immunofluorescence, frozen tissue were cut by 7 μM after embedded with OCT compound and attached to silane coated slide. After drying 10 mins in RT, slides were fixed with cold methanol for 20 mins in −20 °C. Slides were proceeded to permeabilization step with 0.5% triton x-100 and blocked by 3% BSA in TBS-T. Primary antibody (F4/80, ab6640, abcam) was incubated for O/N in 4 °C. After three times of wash with TBS-T, secondary antibody (A21202, Life Technologies) was incubated for 3 hrs in RT. Region of interest was observed in dark area with microscope (DMi8, Leica).

Cell culture

Hep3B cells were cultured in DMEM-High glucose medium (LM 001-05). DMSO and AG-205(10 mg/ml, A1478, sigma) were treated for indicated hours before high fat treatment. Fatty acids (Palmitic acid 330 μM, Oleic acid 660 μM) were treated for each indicated hours.

SiRNA transfection was performed with lipofectamine 2000 (11668-027, Thermofisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Negative control siRNA and PGRMC1 siRNA #1 and #2 were purchased from Bioneer (Daejoen, Korea). The sense sequences of PGRMC1 siRNA #1 and #2 were 5′-CAGUACAGUCGCUAGUCAA-3′ and 5′-CAGUUCACUUUCAAGUAUCA-U-3′.

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from mice by collagenase digestion and Percoll Gradient method. Briefly, mice were anesthetized, and the peritoneal cavity was opened. Livers were perfused with Ca2+ and Mg2+ free-HBSS containing EDTA (1 mM) (LB203-56, Welgene) and then digested with a collagenase solution containing liberase (Research grade, Sigma). Digested livers were removed and rinsed twice with HBSS and then gently teased with forceps until they were in solution. The cell suspensions were filtered through a sterile 40-μm nylon cell strainer (SPL) to remove undigested tissue and connective tissue. The cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 rpm and resuspended with medium. The pellet suspensions were centrifuged using 35% Percoll for 15 min at 2000 rpm with the brake option off. After centrifugation, the healthy hepatocytes were pelleted as damaged hepatocytes, or nonparenchymal cells could not penetrate into 35% Percoll solution. The pellets were washed twice with DMEM supplemented with 5%FBS, and then seeded into six well tissue culture plates. After 24 hrs, nonadherent cells were removed by aspiration.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SD. Differences between means were obtained by Student’s t-test was performed using Graph Pad Software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2015R1D1A1A01060335 and 2018R1D1A1A02043102 to E.-J.H. and 2014R1A1A2057405 to I.-J.B).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

In-Jeoung Baek, Email: ijbaek@amc.seoul.kr.

Eui-Ju Hong, Email: ejhong@cnu.ac.kr.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-34148-6.

References

- 1.Chalasani N, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1592–1609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarantino G, Savastano S, Colao A. Hepatic steatosis, low-grade chronic inflammation and hormone/growth factor/adipokine imbalance. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4773–4783. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i38.4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starley BQ, Calcagno CJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51:1820–1832. doi: 10.1002/hep.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarantino G, Finelli C. What about non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a new criterion to define metabolic syndrome? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3375–3384. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Metabolism. 2016;65:1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onnerhag K, Nilsson PM, Lindgren S. Increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer during long-term follow-up of patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1111–1118. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.934911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarz JM, Linfoot P, Dare D, Aghajanian K. Hepatic de novo lipogenesis in normoinsulinemic and hyperinsulinemic subjects consuming high-fat, low-carbohydrate and low-fat, high-carbohydrate isoenergetic diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:43–50. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimano H, et al. Isoform 1c of sterol regulatory element binding protein is less active than isoform 1a in livers of transgenic mice and in cultured cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:846–854. doi: 10.1172/JCI119248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagen RM, Rodriguez-Cuenca S, Vidal-Puig A. An allostatic control of membrane lipid composition by SREBP1. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2689–2698. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kast-Woelbern HR, et al. Rosiglitazone induction of Insig-1 in white adipose tissue reveals a novel interplay of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and sterol regulatory element-binding protein in the regulation of adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23908–23915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shulman AI, Mangelsdorf DJ. Retinoid x receptor heterodimers in the metabolic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:604–615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobin KA, et al. Cross-talk between fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism mediated by liver X receptor-alpha. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:741–752. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.5.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa T, et al. Cross-talk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and liver X receptor (LXR) in nutritional regulation of fatty acid metabolism. I. PPARs suppress sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c promoter through inhibition of LXR signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1240–1254. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda M, et al. SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) is required for increased lipid synthesis in liver induced by cholesterol deprivation and insulin elevation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1206–1216. doi: 10.1101/gad.891301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu FH, et al. The gene-gene interaction of INSIG-SCAP-SREBP pathway on the risk of obesity in Chinese children. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:538564. doi: 10.1155/2014/538564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong XY, Tang SQ. Insulin-induced gene: a new regulator in lipid metabolism. Peptides. 2010;31:2145–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suchanek M, Radzikowska A, Thiele C. Photo-leucine and photo-methionine allow identification of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:261–267. doi: 10.1038/nmeth752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krebs CJ, et al. A membrane-associated progesterone-binding protein, 25-Dx, is regulated by progesterone in brain regions involved in female reproductive behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12816–12821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selmin O, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel gene induced by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in rat liver. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2609–2615. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.12.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang M, et al. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 is a functional part of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor complex in pancreatic beta cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:3049–3062. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.040196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peluso JJ, Romak J, Liu X. Progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (PGRMC1) is the mediator of progesterone’s antiapoptotic action in spontaneously immortalized granulosa cells as revealed by PGRMC1 small interfering ribonucleic acid treatment and functional analysis of PGRMC1 mutations. Endocrinology. 2008;149:534–543. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohe HJ, Ahmed IS, Twist KE, Craven RJ. PGRMC1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1): a targetable protein with multiple functions in steroid signaling, P450 activation and drug binding. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes AL, et al. Dap1/PGRMC1 binds and regulates cytochrome P450 enzymes. Cell Metab. 2007;5:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai HL, et al. A potential mechanism underlying atypical antipsychotics-induced lipid disturbances. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e661. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satapati S, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism mediates oxidative stress and inflammation in fatty liver. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4447–4462. doi: 10.1172/JCI82204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology. 2010;51:679–689. doi: 10.1002/hep.23280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caldwell SH, Crespo DM, Kang HS, Al-Osaimi AM. Obesity and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S97–103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert JE, Ramos-Roman MA, Browning JD, Parks EJ. Increased de novo lipogenesis is a distinct characteristic of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:726–735. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X, So JS, Park JG, Lee AH. Transcriptional control of hepatic lipid metabolism by SREBP and ChREBP. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:301–311. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rawson RB. The SREBP pathway–insights from Insigs and insects. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:631–640. doi: 10.1038/nrm1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, et al. SREBP-1c overexpression induces triglycerides accumulation through increasing lipid synthesis and decreasing lipid oxidation and VLDL assembly in bovine hepatocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao J, et al. Liver-specific deletion of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 reduces hepatic triglyceride accumulation without affecting glucose homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8552–8557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603115103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Y, et al. SREBP1 regulates tumorigenesis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer through targeting lipid metabolism. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:4133–4141. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, et al. Differential effects of estrogen/androgen on the prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the male rat. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:345–357. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M028969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brookheart RT, Michel CI, Schaffer JE. As a matter of fat. Cell Metab. 2009;10:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li ZZ, Berk M, McIntyre TM, Feldstein AE. Hepatic lipid partitioning and liver damage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5637–5644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807616200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peter A, et al. Individual stearoyl-coa desaturase 1 expression modulates endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in human myotubes and is associated with skeletal muscle lipid storage and insulin sensitivity in vivo. Diabetes. 2009;58:1757–1765. doi: 10.2337/db09-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma S, Jensen D, Hart J, Mohanty SR. Predictive value of ALT levels for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Liver Int. 2013;33:1398–1405. doi: 10.1111/liv.12226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park EJ, et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell. 2010;140:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarantino G, et al. Could inflammatory markers help diagnose nonalcoholic steatohepatitis? European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2009;21:504–511. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283229b40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang L, et al. Transforming growth factor beta signaling in hepatocytes participates in steatohepatitis through regulation of cell death and lipid metabolism in mice. Hepatology. 2014;59:483–495. doi: 10.1002/hep.26698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto M, et al. An improved mouse model that rapidly develops fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2013;94:93–103. doi: 10.1111/iep.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee NP, et al. Proteomic expression signature distinguishes cancerous and nonmalignant tissues in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1293–1303. doi: 10.1021/pr800637z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hampton KK, Stewart R, Napier D, Claudio PP, Craven RJ. PGRMC1 Elevation in Multiple Cancers and Essential Role in Stem Cell Survival. Adv Lung Cancer (Irvine) 2015;4:37–51. doi: 10.4236/alc.2015.43006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang D, et al. PGRMC1 Is a Novel Potential Tumor Biomarker of Human Renal Cell Carcinoma Based on Quantitative Proteomic and Integrative Biological Assessments. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sung YH, et al. Knockout mice created by TALEN-mediated gene targeting. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:23–24. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doyle EL, et al. TAL Effector-Nucleotide Targeter (TALE-NT) 2.0: tools for TAL effector design and target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W117–122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.