Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to assess the impact of radiation dose on rectal toxicity after salvage external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) with or without a brachytherapy boost for exclusive local failures after the primary EBRT for prostate cancer.

Methods and materials

Fourteen patients with no severe residual late toxicity after primary EBRT ± brachytherapy were reirradiated after a median time interval of 6.1 years. The median normalized total dose in 2 Gy fractions (NTD2Gy, α/β ratio = 1.5 Gy for prostate cancer cells) was 74 Gy at primary EBRT and 85.1 Gy at reirradiation. Rectal dose-volume histograms (converted to NTD2Gy_alpha/beta = 3 Gy) and the corresponding normal-tissue complication probability (NTCP) values for gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity were evaluated for 2 groups: High GI toxicity (grade ≥3) and low GI toxicity (grade ≤2).

Results

The 5-year grade ≥3 GI toxicity-free survival rate was 57.1%. The median rectal V70Gy and maximum dose to 1 cm3 (D1ccrect) at primary EBRT were both predictive for grade ≥3 GI toxicity (9% vs 0%; P = .04 and 72.2 Gy vs 66.8 Gy; P < .01, respectively). When adding primary radiation therapy (RT) and reirradiation plans, the median D1ccrect was 139.8 Gy versus 126.7 Gy (P < .01) for high and low GI toxicity groups. NTCP >10% at primary RT was predictive for high GI toxicity at reirradiation (P < .05).

Conclusions

Even in the absence of residual toxicity after primary RT, rectal doses >70 Gy and NTCP >10% calculated for a first irradiation may be associated with a higher risk of developing high GI toxicity at reirradiation with a possible D1ccrect threshold of 130 Gy.

Summary.

Predictors for rectal toxicity were studied from dosimetric data of 14 patients with prostate cancer treated with salvage external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for exclusive failure after primary EBRT. Threshold dose constraints (rectal V70 Gy at first EBRT and a cumulative maximum dose to 1 cm3 of the rectum >130 Gy) and normal-tissue complication probability models were both predictors of severe gastrointestinal toxicities after reirradiation and may be integrated in the optimization of salvage radiation therapy plans.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

There is no wide consensus with regard to the optimal management of recurrent prostate cancer after external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Androgen deprivation therapy is still the most frequently used salvage strategy, even if its long-term use may lead to a marked decline in quality of life1, 2, 3, 4 and its efficacy may fade over time. Alternative approaches of local salvage treatment with curative intent may be proposed for selected cases, in particular for patients with a long life expectancy.

The best salvage modality after exclusive local failure following primary radiation therapy (RT) is still unknown. Several authors have reported their experience with reirradiation with brachytherapy (BT), EBRT, or stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).5, 6, 7 With SBRT, high doses can be delivered with steep dose gradients. Improvements in technology and image guidance as well as a better understanding of the fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer supports SBRT as a challenging alternative to BT for salvage treatment.

Although a few promising preliminary results (up to 2 years of follow-up) with salvage SBRT have been reported,7, 8 longer follow-up intervals are needed to establish the benefits and toxicity of SBRT reirradiation for salvage therapy because severe radiation-induced side effects and relatively poor long-term biochemical control have been reported with >5-year follow up.9

The purpose of this study was to assess the value of the dosimetric data for 14 patients with prostate cancer who were reirradiated with salvage whole-gland EBRT for exclusive local failure after primary RT and with long follow-up times.9 We aimed to study potential risk predictors of severe gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity after salvage reirradiation.

Methods and materials

Fourteen patients with recurrent prostate cancer who had been previously treated with primary RT between 1992 and 2002 were reirradiated between 2003 and 2008 using an EBRT ± BT technique. The median time interval between the 2 RT courses was 6.1 years (range, 4.7-10.2 years). All patients had local-only relapses as confirmed by prostate biopsy (n = 11) and/or radiologic staging images. At recurrence, most patients were free of GI or genitourinary (GU) toxicity. Toxicity was scored in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events toxicity scale version 3.0 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/). While on treatment, patients were seen in status-check visits once weekly, followed by a follow-up visit 6 to 8 weeks after treatment completion, then every 3 months during the first year, and every 6 months thereafter. Follow-up visits involved prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurements, a digital rectal examination, and an assessment of GI and GU toxicities. Patient and tumor characteristics at diagnosis and recurrence have been previously reported.9 Table 1 (and eTables 1 and 2; available as supplementary material online only at www.practical.radonc.org) presents the material description with urinary and rectal toxicity grading as recently published by our group.9

Table 1.

Patients' clinical and dosimetric characteristics

| Patient ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late GI toxicity (grade) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Age at first diagnosis (y) | 66 | 63 | 57 | 54 | 52 | 68 | 58 |

| Age at relapse (y) | 72 | 70 | 64 | 59 | 60 | 73 | 64 |

| Interval time between primary and salvage RT (y) | 5.6 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 5.2 | 4.9 |

| Framingham score | >20% | <20% | >20% CI | <20% | <20% | >20% | >20% |

| Primary RT treatment technique | 6 fields | 6 fields | 4-fields box+6 fields | 5 field+4-fieldsbox | 4-fields box+4-fields box+ 3 fields | 6 fields | 6 fields |

| Primary EBRT dose (Gy) × fraction | 2 × 37 | 2 × 32 | 1.8 × 28 + 2 × 7 | 2.25 × 20 + 2.5 × 8 | 1.8 × 13 + 2 × 13 +2.25 × 8 | 2 × 38 | 2 × 38 |

| Primary BT dose (Gy) × fraction | — | 7 × 2 | 7 × 2 | — | — | — | — |

| Primary RT NTD2Gy (α/β = 1.5 Gy) | 74.0 | 98.0 | 95.5 | 71.1 | 67.3 | 74.0 | 76.0 |

| Salvage RT treatment technique | 4-fields-box | 5-fields IMRT+5-fields IMRT | 5-fields IMRT+5-fields IMRT | 5-fields IMRT | 6-fields | 6-fields | 6-fields |

| Salvage EBRT dose (Gy) × fraction | 1.8 × 25 | 2 × 22 + 4 × 6 | 2 × 21 + 4 × 6 | 2 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 |

| Salvage BT dose (Gy) × fraction | 7 × 3 | — | — | 6 × 3 | 0.5 × 50 | 7 × 3 | 7 × 3 |

| Salvage RT NTD2Gy (α/β = 1.5 Gy) | 91.7 | 81.7 | 79.7 | 88.6 | 56.7 | 73.9 | 93.4 |

| Primary + salvage RT NTD2Gy (α/β = 1.5 Gy) | 165.7 | 179.7 | 175.2 | 159.7 | 124.1 | 147.9 | 169.4 |

| Patient ID | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late GI toxicity (grade) | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Age at first diagnosis (y) | 58 | 74 | 59 | 56 | 67 | 65 | 57 |

| Age at relapse (y) | 66 | 80 | 70 | 65 | 76 | 71 | 62 |

| Interval time between primary and salvage RT (y) | 7.4 | 5.2 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 4.7 |

| Framingham score | >20% | >20% CI | >20% | >20% CI | >20% | >20% | >20% |

| Primary RT treatment technique | 4-fields box+6 fields | 6 fields | 4-fields box+4-fields box | 4-fieldsbox+4-fields box | 6 fields+6 field | 4-fields box+6 fields | 6 fields+6-fields |

| Primary EBRT dose (Gy) × fraction | 1.8 × 28 + 2 × 12 | 2 × 37 | 2 × 23 + 2 × 12 | 2 × 25 + 2 × 12 | 2 × 27 + 2 × 10 | 1.8 × 28 + 2 × 12 | 2 × 27 + 2 × 10 |

| Primary BT dose (Gy) × fraction | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Primary RT NTD2Gy (α/β = 1.5 Gy) | 76.0 | 71.5 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 71.5 | 71.5 | 74.0 |

| Salvage RT treatment technique | 6-fields | 3-fields+7-fields IMRT | 5-fields IMRT | 6-fields | 6-fields | 6-fields | 6-fields |

| Salvage EBRT dose (Gy) × fraction | 1.8 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 + 4 × 5 | 2.25 × 32 | 1.8 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 | 1.8 × 25 |

| Salvage BT dose (Gy) × fraction | 6 × 3 | — | — | 7 × 3 | 7 × 3 | 4 × 6 | 7 × 3 |

| Salvage RT NTD2Gy (α/β = 1.5 Gy) | 93.4 | 81.0 | 77.1 | 93.4 | 93.4 | 80.1 | 93.4 |

| Primary + salvage RT NTD2Gy (α/β = 1.5 Gy) | 169.4 | 152.5 | 147.1 | 163.4 | 164.9 | 151.6 | 167.4 |

BT, brachytherapy; CI, cardiovascular incident (infarctus, angor, or stent); EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; GI, gastrointestinal; ID, identification number; IMRT, intensity modulated radiation therapy; NTD2Gy, normalized total dose in 2 Gy equivalent fraction; RT, radiation therapy.

A median normalized total dose in 2 Gy-fractions (also referred to as 2 Gy equivalent dose; NTD2Gy, α/β ratio = 1.5 Gy for prostate cancer cells) of 74.0 Gy was delivered with the first irradiation. At reirradiation, 10 patients were salvaged with combined EBRT and BT, and the remaining 4 were salvaged with EBRT only (median NTD2Gy = 85.1 Gy). Treatment setup verifications for salvage EBRT and intensity modulated RT (IMRT) were performed using an offline protocol and appropriate patient repositioning was performed on the basis of bone-matching on portal images.

To analyze the data and assess the radiation dose parameters and clinical factors that potentially predict severe long-term GI toxicity, the study population was divided into 2 subgroups: Low-grade toxicity (grade ≤2) and high-grade (≥3) toxicity with 5 and 9 patients, respectively. To analyze GI toxicity, the physical doses (EBRT and BT) were converted into NTD2Gy, using the linear quadratic formula and α/β ratio of 1.5 Gy (prostate) and α/β ratio = 3 Gy (rectum):

where NTD2Gy is the dose delivered in 2 Gy fractions that is biologically equivalent to a total physical dose D (Gy), with d (Gy) the dose per fraction and α/β (Gy) the dose at which the linear and quadratic components of cell kill are equal.10 The results of the NTD2Gy prescription doses are reported per patient in Table 1, for α/β = 1.5 Gy.

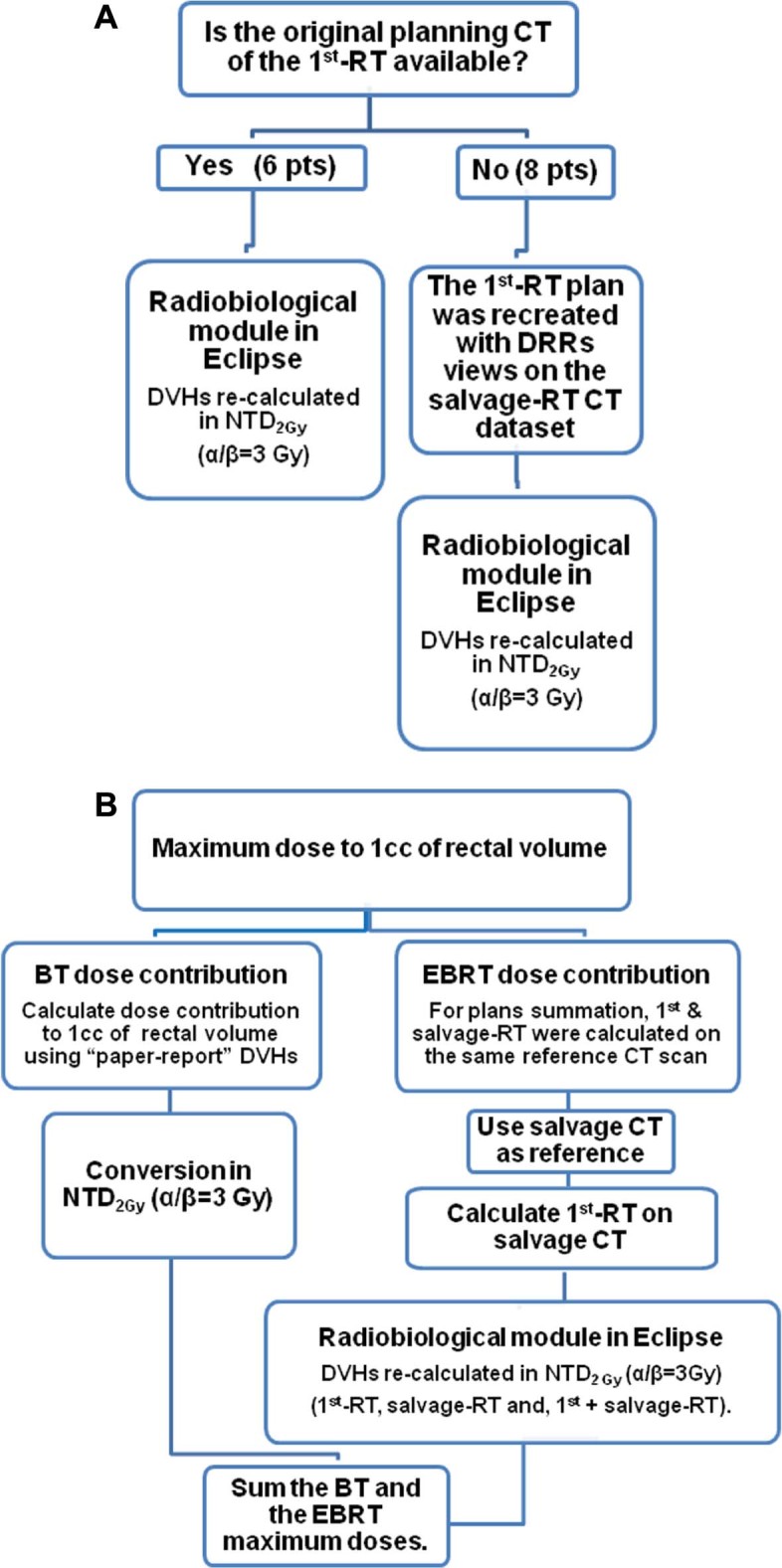

Although salvage EBRT treatment plans were available for all patients and could be recovered from the treatment planning system (TPS; Eclipse, Varian, Palo Alto, CA), EBRT treatment plans for the first irradiation could only be retrieved for 6 of 14 patients. For the remaining 8 patients, the primary RT plans were reconstructed on the computed tomography (CT) data sets of the reirradiation plans (second CT scan) using treatment records in hard-copy format, including simulation and treatment portal films. The study workflow is shown in Figure 1A. The dose-volume histogram (DVH) analysis of treatments plans considered both the percentage of rectal volume and the absolute rectal volume (in cm3) receiving a given dose. DVH paper prints from all primary RT treatment plans were also used to assess the correlation between dose to the rectum at primary treatment and GI toxicity.

Figure 1.

Dosimetric study workflow.

The rectal structures used for the EBRT dose analysis were recontoured on the CT data sets by an expert radiation oncologist using the Male Pelvis Normal Tissue Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Contouring guidelines.11 The rectum was contoured as a solid structure (including the contents) and as a wall structure with a wall thickness of 5 mm (rectal wall). The analytical anisotropic algorithm version 10 was used to calculate the dose distribution for all plans (imported and reconstructed) with a calculation grid resolution of 2.5 mm.

To take into account the heterogeneity of the dose prescriptions (Table 1), Eclipse Biological Evaluation Module version 11 was used to convert the DVH data into equivalent doses delivered in 2 Gy fractions (α/β = 3 Gy for the rectum) in accordance with the linear-quadratic model. To use the Biological Evaluation Module to convert the prescribed dose and DVH data for the primary + salvage RT treatment plans, they were calculated on the same CT data set. Thus, patients' salvage RT data sets were used for the summed plan analysis. The addition of doses in the Biological Evaluation Module was performed without modeling normal tissue recovery time.

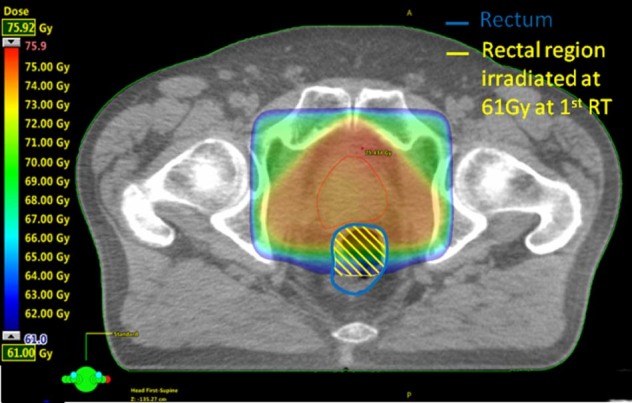

DVH metrics disregard dose distribution spatial information; therefore, different approaches were used to analyze the DVH data: (1) maximum dose to 1 cm3 of the entire rectum (D1ccrect) from the summed (primary + salvage) EBRT; and (2) maximum dose to 1 cm3 of the pre-irradiated high-dose rectal region (D1cc1st-irr_rect). This is defined hereafter as the portion of the rectum that is encompassed by the 61 Gy isodose line (ie, 95% of 64 Gy, the lowest prescription dose at first irradiation; Table 1) as shown in Figure 2. The 1 cm3 rectal volume choice was driven by several facts: (1) restricting the analysis to the rectum receiving 61 Gy from the initial plan resulted in 1 patient with a volume of approximately 1 cm3; (2) a hot spot as defined by 62 International Commission on Radiation Units12 is approximately 1.8 cm3 in volume (volume of a sphere of diameter of 15 mm); (3) ICRU 8313 recommends describing the maximum dose as D2% of the entire organ, which corresponds to 1 cm3 for our series, considering that our median rectal volumes are approximately equal to 50 cm3.

Figure 2.

Example of delineation of the portion of rectal wall treated at 61 Gy at primary radiation therapy.

The BT treatment plans were calculated using the Plato TPS (Nucletron-Odelft, Veenendael, The Netherlands).14 The contribution of the BT dose to the rectum could not be recovered in the EBRT TPS because the plans were no longer accessible in digital format. However, the BT dose to the rectum was available in the form of hard-copy DVH reports. From the BT DVH data, the maximum dose to 1 cm3 of the rectum from the BT plan could be determined. Rectal doses from BT were converted to NTD2Gy (linear quadratic formula, α/β = 3 Gy) for late rectal toxicity.

The BT dose to 1 cm3 of the rectum, as delineated in the BT plans, was summed with the maximum dose to 1 cm3 of the rectum from the EBRT plans (Fig 1B). This approach is based on the assumption that the part of the rectum that is directly adjacent to the prostate is the part that receives the highest dose and that the same rectal portion is abutting the prostate in both treatment scenarios.

Normal-tissue complication probability (NTCP) models were used to estimate the risk of grade ≥2 and ≥3 rectal toxicity on the basis of dosimetric data for all primary RT treatment plans. NTCP values were calculated using the Lyman-Kutcher-Burman model15, 16 using parameters from the literature (Table 2).17, 18, 19, 20, 21 NTCP included models with an α/β value >3 Gy.

Table 2.

Rectal toxicity NTCP (Lyman-Kutcher-Burman) after first irradiation for the 14 patients in the study by different models

| Reference | Toxicity grade/endpoint | Rectal organ segmentation | D50, Gy | α/β, Gy | n | m | NTCP median (range) Grade 0-2/Grade 3-4 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dale et al.17 | Grade ≥3/late effects | Rectal wall | 80 | 3.9 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 6.0 (1.8-12)/11 (5.5-20.0) | .05 |

| Rancati et al.18 | Grade ≥3/bleeding | Rectum solid organ | 78.6 | 3 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.0 (0-0.3)/0.2 (0.0-7.4) | .05 |

| Michalski et al.19 | Grade ≥2/bleeding | Rectum solid organ | 76.9 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 4.3 (0.7-10.7)/8.2 (1.6-18.4) | .16 |

| Tucker et al.20 | Grade ≥2/bleeding | Rectum solid organ | 77.9 | 4.8 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 6.7 (0.9-14.0)/11.2 (4.2-30.8) | .03 |

| Gulliford et al.21 | Grade ≥2/bleeding | Rectum solid organ | 68.9 | 3 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 14.8 (1.3-25.0)/22.5 (2.8-56.4) | .26 |

| Rancati et al.18 | Grade ≥2/bleeding | Rectum solid organ | 81.8 | 3 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 10.2 (1.8-15.4)/7.7 (1.5-13.8) | .64 |

D50, dose giving a 50% response probability; n, volume dependence factor; NTCP, normal tissue complication probability; m, slope of the response curve.

Patient-related factors that potentially influence the severity of vascular morbidity and thus increase the risk for rectal reirradiation damage are age, sex, high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol levels. The Framingham risk score, which is estimated with all these risk factors, was conceived to predict the 10-year cardiovascular risk of an individual and was chosen in our analysis to stratify patients into 2 groups with a standard cutoff of 20%: one with a low score (<20% risk) and another with a high score (≥20% risk).22 Both risk groups were correlated with rectal toxicity severity after reirradiation.

A Mann-Whitney test was used to evaluate independently several factors between the patients stratified in low- and high-grade GI toxicity groups (time-interval between primary RT and reirradiation, age, DVH parameters, and NTCP data). A two-tailed Fisher exact test was used for the cross-comparison between the Framingham score and pelvic RT versus toxicity (grade 0-2 vs grade 3-4). The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS package (SPSS Statistics version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

The median rectal volumes for patients with (n = 9) or without (n = 5) grade ≥3 GI toxicity were similar (51 vs 59 cm3; P > .05). The median time-interval between primary RT and salvage RT for the low- and high-grade toxicity groups were similar (6.6 vs 5.8 years; P > .05). Age (median) was not statistically different between the 2 toxicity groups at the time of the first (57 vs 59 years; P > .05) and salvage irradiation (64 vs 70 years; P > .05). No differences between the 2 groups were observed with regard to pelvic node RT (P > .05). Only 3 of the 13 patients in the study presented with a Framingham risk score <20%, and all 3 belonged to the low-grade toxicity group (P = .03).

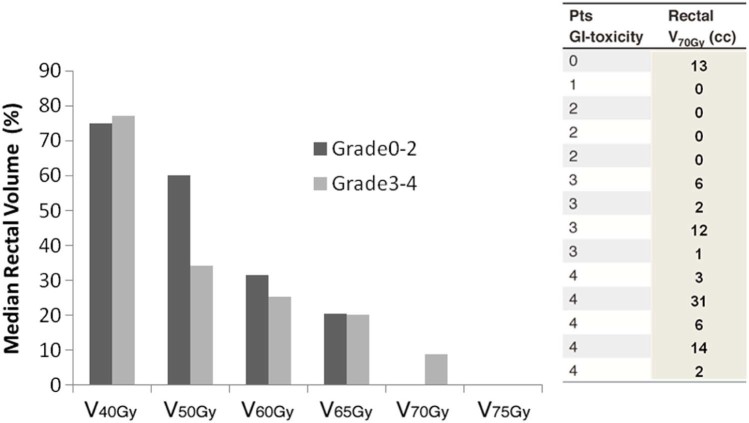

As shown in Figure 3, primary EBRT treatment plans using simulation CT data for salvage showed that the percent of rectal volume that received ≥70 Gy (NTD2Gy_α/β = 3) was statistically significant for grade ≥3 versus grade ≤2 GI toxicity at reirradiation (9% vs 0%; P = .04; Fig 3). The corresponding median volume that received 70 Gy was 6 cm3 (range, 1-31 cm3) and 0 cm3 (range, 0-13 cm3) for the high- and low-grade toxicity groups, respectively (Fig 3). Using original DVH paper prints, the percentage of rectal volume that received ≥70 Gy was correlated significantly with grade ≥3 versus grade ≤2 GI toxicity at reirradiation (6% vs 0%; P = .04). The corresponding median volumes that received 70 Gy were 3 cm3 (range, 1-17 cm3) and 0 cc (range, 0-8 cm3) for the high- and low-grade toxicity groups, respectively.

Figure 3.

Histograms representing the percentage of median rectal volume receiving a specific dose with the first irradiation. Patients are stratified into 2 groups by GI toxicity severity (grade 0-2 vs grade 3-4). V70Gy (in cm3)for every patient, on the right side of the figure.

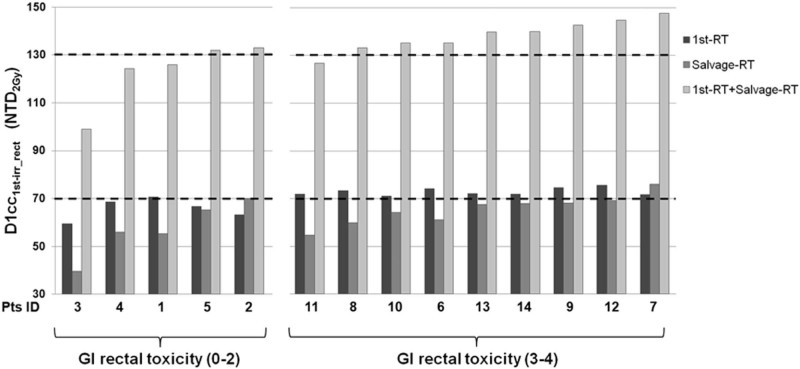

Although the median (range) value of the maximum NTD2Gy D1cc1st-irr_rect at first irradiation was statistically different between the high- and low-grade GI toxicity groups (ie, 72.2 Gy [71.0-75.6 Gy] vs 66.8 Gy [59.5-70.6 Gy], respectively; P < .01), no statistical difference was seen at salvage RT (ie, 67.6 Gy [54.7-69.2 Gy] vs 55.9 Gy [39.6-70.0 Gy], respectively; P > .05). When summing the first irradiation and reirradiation treatment plans, including BT, the median (range) NTD2Gy D1cc1st-irr_rect was 139.8 Gy (126.7-147.8 Gy) versus 125.9 Gy (99.4-133.1 Gy; P = .01) for the high- and low-grade GI toxicity groups, respectively (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Maximum dose (NTD2Gy, α/β = 3 Gy) to 1 cm3 of rectum treated at high doses at first irradiation (D1cc1st-irr-rect) as a function of treatment for each patient.

When analyzing the added total dose to the entire rectum, the median (range) value of the maximum NTD2Gy D1ccrect was significantly different (139.8 Gy [127.0-147.8 Gy] vs 126.7.0 Gy [124.4-133.1 Gy]; P < .01) between the high- and low-grade GI toxicity groups. For all but 1 patient, the portion of the high dose to the rectum at reirradiation was within the region of the high dose at primary RT. Only in 1 patient (patient 3), the 1 cm3 rectal volume that received the maximum dose at the first and salvage irradiation regions were located in different spots within the rectal wall.

As shown in Table 2, NTCP estimations after primary RT using the model by Tucker et al. (α/β = 4.8 Gy for late severe GI rectal toxicity; P = .03) showed the best results to predict toxicity after reirradiation.20 We used this α/β value to recalculate DVHs and BT doses for the plan sum. We observed that the median (range) value of the maximum NTD2Gy D1ccrect was still significantly different (135.3 Gy [120.2-140.9 Gy] vs 125.8 Gy [116.3-129.8 Gy]; P = .03) between the high- and low-GI toxicity groups.

Discussion

To minimize toxicity and optimize the success of local salvage treatment, the appropriate selection of patients is of paramount importance. A long PSA doubling time, a low PSA value at relapse, an interval between first treatment and PSA failure of >3 years, and a low Gleason score at re-biopsy are factors that suggest a reasonable likelihood of isolated recurrence within the prostate.3, 6 However, when salvage reirradiation is considered, the residual biological harm to the rectum from previous irradiation treatment needs to be taken into account. In the present study, the impact of dose on long-term rectal toxicity after reirradiation of the prostate with EBRT (±BT) has been assessed in a small population of 14 patients with local recurrence after primary EBRT (±BT).

To our knowledge, this is the first report to assess the value of dosimetric and clinical parameters at first irradiation as risk indicators for severe late complications after salvage reirradiation. Our observations suggest that the ability of the rectum to repair damage from a second EBRT salvage irradiation may depend on the dose received by the same rectal portion from the first irradiation, as well as on the total dose received by the rectum after salvage RT.

Although a long-enough time interval (>4 years) between primary and salvage RT has been proposed as a safe measure to reduce the severity of GI toxicity at reirradiation,3, 23 we were unable to confirm this hypothesis in our study. Instead, the volume of the rectum irradiated to high doses (≥70 Gy) at first RT correlated well with the severity of late GI toxicity, regardless of the time interval between primary and salvage RT.

Furthermore, we observed a significant risk for late grade ≥3 toxicity for summed doses above 130 Gy to 1 cm3 of rectal volume. The influence of the dose to the rectum after primary EBRT was observed both with the DVH analysis and with well-known NTCP models. Indeed, NTCP values obtained from primary EBRT treatment plans were estimated using several models (Table 2).

Restricting the analysis to the hottest portion of the rectum from the first and salvage irradiations suggests the existence of a threshold dose (NTD2Gy_α/β = 3 Gy) of 130 Gy for rectal high-grade GI toxicity (both for α/β = 3 or 4.8 Gy). In the present study, the delivery of a relatively low dose at first irradiation and a more focal reirradiation (IMRT, BT boost) keeping the D1ccrect <130 Gy might have helped reduce the risk of severe rectal side effects. The hypothesis may be supported by reports on BT for salvage RT because reducing the dose to the rectum at reirradiation can limit the incidence of grade 3 to 4 rectal toxicity to <5% (range, 0-20%).24

Additional data from the literature support the concept of threshold. Kim et al.25 reported that, for dose-escalated prostate SBRT, an increased risk of late rectal toxicity correlated with a concomitant high percentage of the circumference of the rectal wall that was irradiated to higher dose levels (39 Gy in 5 fractions) and 3 cm3 of rectum irradiated to 50 Gy in 5 fractions. Interestingly, their fractionation and dose correspond to a NTD2Gy of 130 Gy, (α/β = 3 Gy). The study by Kim et al.25 might also point out the importance of a rapid dose fall-off around the hot spot in the rectum (ie, dose-volume effects), which might help RT damage repair and possibly explain the low rate of rectal toxicities reported by BT studies.24, 26

The knowledge of the dose distribution for the rectum is essential to correlate toxicities with plans. As visible for 2 patients (Table 1; patients 2 and 3) who were treated with a BT boost at primary RT, the NTD2Gy_α/β = 3 Gy prescription dose was high while the dose to 1 cm3 of rectum was much smaller (Fig 4). Furthermore, 2 patients were treated with exclusive EBRT, both at primary and salvage RT (patients 9 and 10), and both developed GI toxicity grade ≥3. Nevertheless, only future studies using a segmental DVH analysis of the rectum might improve the knowledge of geometrical and dose-volume effects on GI toxicity.27

Furthermore, the NTCP parameters proposed by Tucker et al.20 were the most reliable predictors for rectal toxicity after reirradiation. The estimated NTCP with low n values suggested, not surprisingly, that high doses are most determinant,28 with the rectum responding radio-biologically like a serial organ. In addition, Brenner29 speculated on late rectal bleeding as an intermediate between a classic late effect and early response, with α/β values intermediate between 3 Gy and 8 Gy.

We wish to highlight that in this study, the incidence of late severe rectal toxicity at reirradiation was extremely high, though much alike the reported toxicity in one dose escalation SBRT study, which delivered a NTD2Gy_α/β = 3 Gy of 130 Gy.25

For salvage RT in the NRG02526 trial, Crook et al.30 observed a 14% crude rate of grade 3 toxicity at a median follow up of 54 months, which is below the 20% rate that is considered unacceptable. However, in this trial, reirradiation was performed using permanent seed BT, a technique known to minimize reirradiation of the rectal wall. A longer follow-up period is probably needed to confirm that grade 2 late toxicity does not evolve in grade 3 adverse events as observed in our series. In fact, as previously demonstrated by Kaplan-Meier estimations,9 the occurrence of grade ≥3 side effects was a late event in our population, with a median onset occurring after 5 years of follow-up (late Grade ≥2 GU: median toxicity free-survival 39 months [range, 6-145 months]; late grade ≥3 GU: median toxicity free-survival 97 months [range, 6-145 months]; late grade ≥2 GI: median toxicity free-survival 15 months [range, 6-69 months]; late grade ≥3 GI: median toxicity free-survival 69 months [range, 9-95 months]). With a median follow-up time after reirradiation of 94 months (range, 48-172 months), the 5- and 8-year probability for grade ≥3 late GI toxicity-free survival was 57.1% ± 13.2% and 27.2% ± 14.3%, respectively. For GU, the toxicity-free survival rates were 77.9% ± 11.3% and 55.7% ± 15.6%, respectively, at 5 and 8 years.

There are several flaws and pitfalls that may have biased the reported results in this retrospective, small assessment. Among these, the most significant may be the approximate estimations and assumptions that were made to reconstruct the dosimetric contribution of the BT boosts and the missing of some original treatment plans that were only available on paper; the absence of IMRT/image guided RT at primary RT to ensure that the planned doses were accurately and precisely delivered at each fraction; the lack of patient-reported outcomes and quality-of-life assessments; and other clinical or dosimetric variables that were not taken into account in this study. Indeed, as the severity of post-reirradiation rectal toxicity may also be influenced by patients' cardiovascular health status and its possible impact on the peripheral microvasculature,31 stratifying patients by Framingham risk score at the time of first treatment appears to correlate with toxicity, which adds a confounding factor in the genesis of post-reirradiation rectal damage.

Conclusions

As for any late-responding normal tissue, the rectal mucosa exposed to high RT doses harbours silent subclinical damage that predisposes patients to severe side effects after reirradiation. The estimated risk of rectal toxicity after the first irradiation may predict the severity of late rectal side effects after reirradiation. A safe threshold dose for the rectum, aiming to optimally prevent the risk of grade ≥3 rectal toxicity may be to keep the summed dose below 130 Gy to any hot spot in the rectum. Salvage whole-gland reirradiation should be used with extreme care.

Footnotes

Predictors for rectal toxicity were studied from dosimetric data of fourteen prostate cancer patients treated with salvage external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for exclusive failure after primary EBRT.

Threshold dose constraints (rectal V70Gy at 1st EBRT and a cumulative maximum dose to 1 cc of rectum > 130 Gy) and NTCP models were both predictors of severe gastrointestinal toxicities after re-irradiation and may be integrated in optimization of salvage-RT plans.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary material for this article (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adro.2018.06.001) can be found at www.practicalradonc.org.

Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Acute and late (maximum score after re-irradiation) genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity scores (CTCAE v3.0 scale): (n =14).

Late gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity scores (CTCAE v3.0 scale).

References

- 1.Mendenhall W.M., Henderson R.H., Hoppe B.S., Nichols R.C., Mendenhall N.P. Androgen deprivation therapy and definitive radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:530–534. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31821dee4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossfeld G.D., Stier D.M., Flanders S.C. Use of second treatment following definitive local therapy for prostate cancer: Data from the caPSURE database. J Urol. 1998;160:1398–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen P.L., D'Amico A.V., Lee A.K., Suh W.W. Patient selection, cancer control, and complications after salvage local therapy for postradiation prostate-specific antigen failure: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer. 2007;110:1417–1428. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith D.P., King M.T., Egger S. Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4817. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyer D.C. Brachytherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:158–165. doi: 10.1053/srao.2003.50015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong W.W., Buskirk S.J., Schild S.E., Prussak K.A., Davis B.J. Combined prostate brachytherapy and short-term androgen deprivation therapy as salvage therapy for locally recurrent prostate cancer after external beam irradiation. J Urol. 2006;176:2020–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jereczek-Fossa B.A., Beltramo G., Fariselli L. Robotic image-guided stereotactic radiotherapy, for isolated recurrent primary, lymph node or metastatic prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leroy T., Lacornerie T., Nickers P., Lartigau E., Pasquier D. Robotic SBRT for locally advanced prostate cancer recurrence following radiation therapy: Preliminary results of a single institution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:E200. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zilli T., Benz E., Dipasquale G., Rouzaud M., Miralbell R. Reirradiation of prostate cancer local failures after previous curative radiation therapy: Long-term outcome and tolerance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler J.F. The linear-quadratic formula and progress in fractionated radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1989;62:679–694. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-62-740-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gay H.A., Barthold H.J., O'Meara E. Pelvic normal tissue contouring guidelines for radiation therapy: A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group consensus panel atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e353–e362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements . 1999. ICRU Report 62: Prescribing, recording, and reporting photon beam therapy (Supplement to ICRU Report 50) Bethesda, MD:ICRU. [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements . 2010. The ICRU Report 83: Prescribing, recording and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) Bethesda, MD:ICRU. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ares C., Popowski Y., Pampallona S. Hypofractionated boost with high-dose-rate brachytherapy and open magnetic resonance imaging-guided implants for locally aggressive prostate cancer: a sequential dose-escalation pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyman J.T. Complication probability as assessed from dose-volume histograms. Radiat Res. 1985;8:S13–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutcher G.J., Burman C., Brewster L., Goitein M., Mohan R. Three-dimensional photon treatment planning report of the collaborative working group on the evaluation of treatment planning for external photon beam radiotherapy histogram reduction method for calculating complication probabilities for three-dimensional treatment planning evaluations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:137–146. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dale E., Hellebust T.P., Skjonsberg A., Hogberg T., Olsen D.R. Modeling normal tissue complication probability from repetitive computed tomography scans during fractionated high-dose-rate brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy of the uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:963–971. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rancati T., Fiorino C., Gagliardi G. Fitting late rectal bleeding data using different NTCP models: Results from an Italian multi-centric study (AIROPROS0101) Radiother Oncol. 2004;73:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michalski J.M., Gay H., Jackson A., Tucker S.L., Deasy J.O. Radiation dose-volume effects in radiation-induced rectal injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S123–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker S.L., Thames H.D., Michalski J.M. Estimation of alpha/beta for late rectal toxicity based on RTOG 94-06. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulliford S.L., Partridge M., Sydes M.R., Webb S., Evans P.M., Dearnaley D.P. Parameters for the Lyman Kutcher Burman (LKB) model of Normal Tissue Complication Probability (NTCP) for specific rectal complications observed in clinical practise. Radiother Oncol. 2012;102:347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmood S.S., Levy D., Vasan R.S., Wang T.J. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: A historical perspective. Lancet. 2013;383:999–1008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crehange G., Roach M., 3rd, Martin E. Salvage reirradiation for locoregional failure after radiation therapy for prostate cancer: Who, when, where and how? Cancer Radiother. 2014;18:524–534. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2014.07.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramey S.J., Marshall D.T. Re-irradiation for salvage of prostate cancer failures after primary radiotherapy. World J Urol. 2013;31:1339–1345. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0953-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D.W., Cho L.C., Straka C. Predictors of rectal tolerance observed in a dose-escalated phase 1-2 trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vargas C., Swartz D., Vashi A. Salvage brachytherapy for recurrent prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2014;13:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenmark M.H., Conlon A.S., Johnson S. Dose to the inferior rectum is strongly associated with patient reported bowel quality of life after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks L.B., Yorke E.D., Jackson A. Use of normal tissue complication probability models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner D.J. Hypofractionation for prostate cancer radiotherapy–what are the issues? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:912–914. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crook J.M., Zhang P., Pisansky T.M. A prospective phase 2 trial of transperineal ultrasound-guided brachytherapy for locally recurrent prostate cancer after external beam radiation therapy (NRG/RTOG0526): Initial report of late toxicity outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;99:S1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joosten M.M., Pai J.K., Bertoia M.L. Associations between conventional cardiovascular risk factors and risk of peripheral artery disease in men. JAMA. 2012;308:1660–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Acute and late (maximum score after re-irradiation) genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity scores (CTCAE v3.0 scale): (n =14).

Late gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity scores (CTCAE v3.0 scale).