Abstract

The heme a molecule is an obligatory cofactor in the terminal enzyme complex of the electron transport chain, cytochrome c oxidase. Heme a is synthesized from heme o by a multi-spanning inner membrane protein, heme a synthase (Cox15 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae). The insertion of heme a is critical for cytochrome c oxidase function and assembly, but this process has not been fully elucidated. To improve our understanding of heme a insertion into cytochrome c oxidase, here we investigated the protein–protein interactions that involve Cox15 in S. cerevisiae. In addition to observing Cox15 in homooligomeric complexes, we found that a portion of Cox15 also associates with the mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes. When supercomplex formation was abolished, as in the case of stalled cytochrome bc1 or cytochrome c oxidase assembly, Cox15 maintained an interaction with select proteins from both respiratory complexes. In the case of stalled cytochrome bc1 assembly, Cox15 interacted with the late-assembling cytochrome c oxidase subunit, Cox13. When cytochrome c oxidase assembly was stalled, Cox15 unexpectedly maintained its interaction with the cytochrome bc1 protein, Cor1. Our results indicate that Cox15 and Cor1 continue to interact in the cytochrome bc1 dimer even in the absence of supercomplexes or when the supercomplexes are destabilized. These findings reveal that Cox15 not only associates with respiratory supercomplexes, but also interacts with the cytochrome bc1 dimer even in the absence of cytochrome c oxidase.

Keywords: cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), membrane protein, mitochondria, respiratory chain, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cox15, cytochrome bc1 (complex III), heme a synthase, mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes, protein-protein interaction

Introduction

Cytochrome c oxidase, a large multisubunit enzyme in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, plays a vital role in aerobic respiration in eukaryotic organisms. Serving as the terminal electron acceptor in the electron transport chain, cytochrome c oxidase catalyzes the reduction of O2 to two water molecules while four protons are pumped across the inner mitochondrial membrane (1–3). For this chemistry to occur, two heme a molecules must be properly inserted into Cox1, the catalytic heme-containing subunit of cytochrome c oxidase (2–7).

Heme a is synthesized via a series of reactions catalyzed by two integral membrane proteins, heme o synthase (Cox10) and heme a synthase (Cox15), which are located in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Cox10 catalyzes the conversion of a heme b molecule into a heme o molecule. Then, in a process that has not been fully elucidated, heme o is further modified into heme a by Cox15 (7–12). The only known destination for the resulting heme a is cytochrome c oxidase (11). Whereas much progress has been made in understanding the assembly of cytochrome c oxidase, very little is known about how heme a is inserted into Cox1. Because of the reactive nature of heme a, due in part to its increased reduction potential relative to the other types of heme (13), it is thought that heme insertion into Cox1 either occurs co-translationally or that a protein chaperone delivers heme from Cox15 to cytochrome c oxidase (14).

It has been debated whether the inner membrane protein, Shy1 (Surf1 in humans and bacteria), acts as the metallochaperone that delivers heme a to cytochrome c oxidase or whether it strictly mediates the protein environment around the heme a site during heme insertion into Cox1. Studies in the bacterium Paracoccus denitrificans indicate that Surf1 is capable of binding heme, suggesting a role in heme a delivery to Cox1 (15, 16). In contrast, work in Saccharomyces cerevisiae has not been able to demonstrate that Shy1 is capable of binding heme, but it has revealed that Shy1 is present in the early assembly intermediate complexes that exist with Cox1 near the time of heme insertion (7, 17, 18). Additionally, Shy1 must be present for Cox1 to be fully hemylated (17). This work in yeast suggests that Shy1 acts as a scaffold during heme insertion into Cox1 rather than a heme binding and delivery protein. Unraveling the protein–protein interactions that occur with Cox15 may better inform us of the protein interactions that occur following heme a synthesis and delivery to cytochrome c oxidase.

It has been established that Cox15 exists in high-molecular weight protein complexes, as observed via blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE)2 (8, 10, 19). Recently, it has been shown that these complexes largely represent oligomers of Cox15 that are stabilized by strong hydrophobic interactions (8), and some evidence may suggest that Cox15 is able to interact sub-stoichiometrically with assembling Cox1 (10). Additionally, Bareth et al. (10) suggest that Cox15 may interact with Shy1 within some of the lower Cox15-containing complexes, an interesting observation given the suggestion that Shy1 may be a heme chaperone. Both determining the identity of the proteins that interact with Cox15 in the Cox15 high-molecular weight complexes and understanding how the complexes are regulated have been equally perplexing. Cox15 high-molecular weight complexes still form in cytochrome c oxidase mutants, when Cox15 is catalytically inactive, and when there is an impairment in heme o biosynthesis (8, 10, 20). Two recent findings have begun to shed light on some of the factors that are important in Cox15 oligomerization. First, the unstructured linker region that connects the N- and C-terminal halves of Cox15 has been shown to be important for Cox15 function and its oligomerization, although it does not seem to significantly impact the steady-state levels of Cox15 (8). Second, the previously uncharacterized Pet117, known to be important for cytochrome c oxidase assembly, was shown to interact with Cox15 and is the first protein identified that when knocked out abolishes the Cox15 complexes observed on BN-PAGE (9). Interestingly, however, Cox15 was still found to interact with itself in the absence of Pet117, indicating that Pet117 is important for the stabilization but not the formation of the Cox15 oligomers (9).

In this report, we analyzed the Cox15 complexes to further elucidate heme a delivery to cytochrome c oxidase. We have found, like Swenson et al. (8), that much of the Cox15 complexes reflect oligomeric states of Cox15, but that in addition to oligomeric Cox15, two of the Cox15 complexes reflect the presence of Cox15 within respiratory supercomplexes. Our results indicate that a relatively small amount of Cox15 is present within the supercomplexes, suggesting that Cox15 only exists within a subset of respiratory supercomplexes. We probed for interactions that occur between Cox15 and proteins of the cytochrome bc1 complex as well as cytochrome c oxidase. We found that Cox15 is capable of interacting with Cor1 from the cytochrome bc1 complex as well as Cox5a and Cox13 from cytochrome c oxidase, presumably within the supercomplexes. Interactions with Cox13 appear to be maintained in the absence of supercomplexes. Of particular interest was the finding that Cox15 and Cor1 interact in the absence of supercomplexes, likely within the dimer of cytochrome bc1. Thus, it appears that not only is a portion of Cox15 present in the supercomplexes, but also that its presence within the supercomplexes may be mediated by the cytochrome bc1 protein, Cor1.

Results

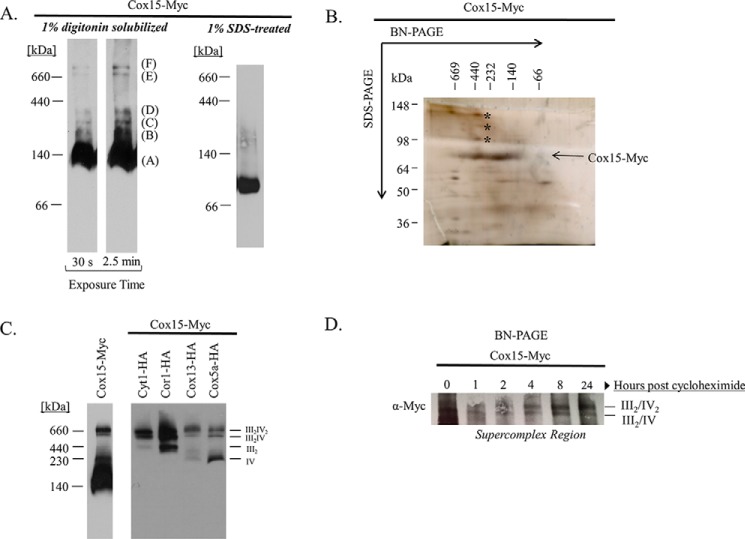

Cox15-Myc exists in both oligomeric high-molecular weight protein complexes and protein complexes that reveal the presence of Cox15 within respiratory supercomplexes

In an effort to understand the protein–protein interactions that occur with Cox15, we observed the distribution of Cox15 with a 13× C-terminal Myc tag (Cox15-Myc) via BN-PAGE. The Cox15-Myc complexes that we observed range in size from about 140 kDa to larger than 660 kDa (Fig. 1A). Consistently, Cox15-Myc distributes primarily in the lowest complex, which migrates at ∼140 kDa, and its distribution in the upper complexes is less abundant. We were able to break apart the high-molecular weight Cox15-Myc complexes with SDS and observed a single band migrating between the 66- and 140-kDa molecular weight markers (Fig. 1A), likely reflecting monomeric Cox15-Myc, which is 75 kDa with the 13× Myc tag. The upper complexes we observe ranging from ∼232 kDa to larger than 660 kDa on BN-PAGE clearly represent Cox15 high-molecular weight protein complexes, as these complexes are about 3–13 times greater in size than monomeric Cox15.

Figure 1.

Blue native PAGE of Cox15-Myc13 reveals the presence of Cox15 in oligomeric complexes and within respiratory supercomplexes. A, Western blotting of BN-PAGE using mitochondria containing a 13× C-terminal Myc tag on Cox15 (Cox15-Myc) solubilized in either 1% digitonin (repeated with numerous biological replicates) or 1% SDS (repeated in three independent experiments (biological replicates)). Both blots represent 10 μg of mitochondria and are probed with an anti-Myc antibody. B, silver stain of a 2D BN/SDS-PAGE of purified Cox15-Myc using nondenaturing anti-c-Myc purification (repeated in two independent experiments (biological replicates)). The three bands marked by an asterisk, the band representing Cox15-Myc ranging from ∼140–250 kDa, and the Cox15-Myc band around 440 kDa were excised and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (experiment performed once). C, Western blotting from BN-PAGE of Cox15-Myc probed with anti-Myc and of Cyt1-HA, Cor1-HA (cytochrome bc1), Cox13-HA, and Cox5a-HA (cytochrome c oxidase) probed with anti-HA. The anti-Myc blot represents 100 μg of mitochondria, and the anti-HA blot shows 50 μg of mitochondria (experiment repeated in at least three biological replicates). D, Western blotting from BN-PAGE of the supercomplex region of Cox15-Myc 0–24 h after cycloheximide addition (10 μg of mitochondria). The experiment was repeated twice independently (biological replicates).

Recently, it was reported that Cox15 in yeast forms stable, oligomeric complexes (8). Our work concurs with the assessment that many of the Cox15 complexes represent Cox15 multimers. One of the strategies we undertook to identify other proteins that may be part of the Cox15 complex was 2D blue native-SDS-PAGE (BN/SDS-PAGE). Cox15-Myc was purified from S. cerevisiae using nondenaturing anti-Myc chromatography and run on BN-PAGE. A lane from the blue native gel was excised and mounted to the top of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Following SDS-PAGE, the gel was silver-stained (Fig. 1B). This allowed us to observe the distribution of purified Cox15 in the high molecular weight complexes as well as any other proteins that are part of the complex. Other proteins will appear either above or below Cox15 on the SDS-polyacrylamide gel. In our 2D gels, Cox15 can be observed in high-molecular weight complexes ranging from ∼140 to 600 kDa. In particular, the 2D gel showed Cox15 associating in two distinct areas. Cox15 is most enriched around 440 kDa and in a broader range between ∼140 and 250 kDa. Both the higher-molecular mass band at 440 kDa and the broad band from 140–250 kDa were excised and analyzed by MS to determine whether any other proteins with the same molecular weight as Cox15-Myc were also present in these bands. Cox15 was the only protein identified by MS in both of the bands analyzed.

In addition, we compared the BN/SDS-polyacrylamide gels of purified Cox15-Myc and purified, untagged mitochondrial extract, and we detected very few obvious differences in the protein bands above and below Cox15 between the two gels (Fig. 1B) (data not shown). The bands we did excise and analyze by MS are indicated with an asterisk. The protein concentration of these bands was not high enough to positively identify these proteins, indicating that no other protein can be detected forming a stoichiometric complex with Cox15 within the purified high-molecular weight complexes. Based on these data and the findings of others (8), it seems likely that the Cox15-Myc complexes A–D in Fig. 1A represent mostly homooligomeric complexes.

Interestingly, the two Cox15 complexes observed via BN-PAGE higher than 660 kDa in Fig. 1A resemble the complex III–containing and complex IV–containing supercomplexes reported by Schagger and Pfeiffer (21) and Cruciat et al. (22). These complexes are represented by bands E and F in Fig. 1A and match the distribution of HA-tagged cytochrome bc1 and cytochrome c oxidase proteins within the respiratory supercomplexes (Fig. 1C). Whereas only a small proportion of Cox15-Myc appears to be present within these putative respiratory supercomplex bands, we noted that Cox15-Myc is stably present within them. Cox15-Myc levels remain largely unchanged, including within the high-molecular weight bands of the supercomplexes (Fig. 1D), at least 24 h following the addition of the translation inhibitor, cycloheximide.

Cox15-Myc interacts with Cor1 of the cytochrome bc1 complex and subunits from cytochrome c oxidase

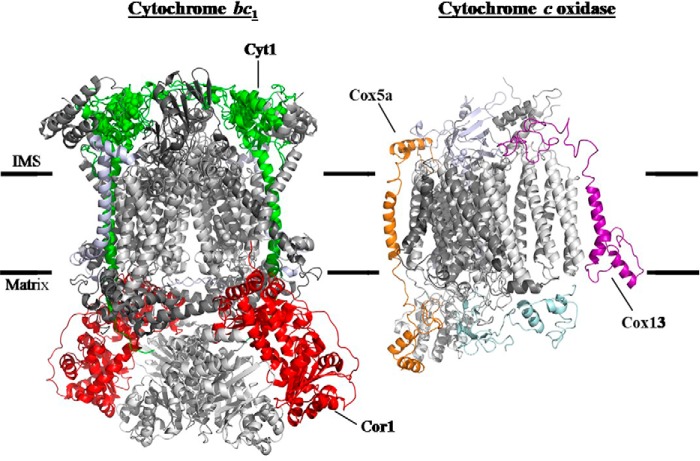

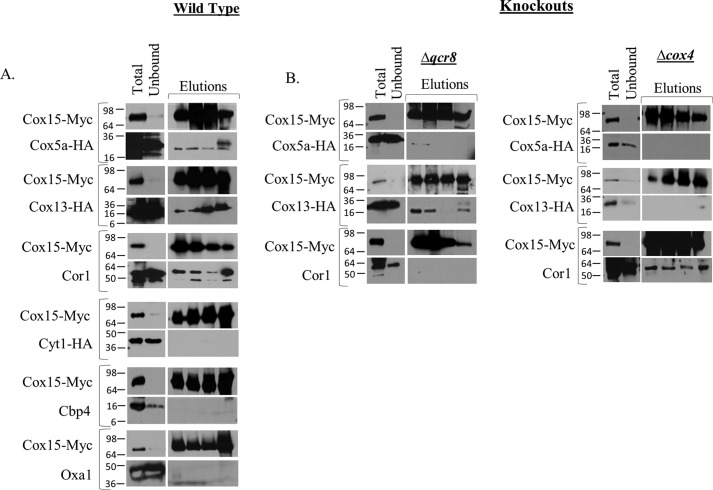

To test whether the two Cox15 complexes larger than 660 kDa represent Cox15 in association with respiratory supercomplexes, we probed for an interaction of Cox15 with selected proteins from both cytochrome c oxidase and the cytochrome bc1 complex. A hemagglutinin (HA) tag was appended to the C terminus of Cox5a and Cox13, two cytochrome c oxidase subunits (Fig. 2). Additionally, an HA tag was appended to the C terminus of the Cyt1 protein, and an antibody recognizing Cor1 was used to assess the presence of cytochrome bc1 (Fig. 2). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments pulling down Cox15-Myc revealed that Cox13-HA from cytochrome c oxidase as well as Cor1 from cytochrome bc1 could be detected with Cox15-Myc (Fig. 3A). In addition, a weak band representing Cox5a-HA from cytochrome c oxidase was also found to co-immunoprecipitate with Cox15-Myc (Fig. 3A). Curiously, we were not able to detect a significant interaction between Cox15-Myc and Cyt1-HA. Control co-immunoprecipitation experiments in which Cox15 did not contain a Myc tag were performed to ensure that Cox5a-HA, Cox13-HA, and Cor1 did not bind adventitiously to the anti-Myc resin (Fig. S1). Two additional controls were performed that utilized the proteins Oxa1, a five-transmembrane inner membrane protein that served as a hydrophobic control, and Cbp4, a cytochrome bc1 assembly factor that is not itself part of fully assembled cytochrome bc1. Both proteins did not co-immunoprecipitate with Cox15-Myc (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the positive interactions we observed are not artifacts occurring during the solubilization and co-immunoprecipitation procedures (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Proteins from cytochrome c oxidase and cytochrome bc1 used to assess co-immunoprecipitation with Cox15-Myc13. A C-terminal HA tag was appended to Cox5a (shown in orange) and Cox13 (purple) of cytochrome c oxidase as well as the Cyt1 (green) protein of cytochrome bc1. An antibody recognizing Cor1 (red) of cytochrome bc1 was also used. This figure was prepared using a crystal structure of S. cerevisiae cytochrome bc1 (58) (Protein Data Bank entry 3CX5) and a homology model of S. cerevisiae cytochrome c oxidase based on the bovine crystal structure (59).

Figure 3.

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments using anti-Myc resin to pull down Cox15-Myc13 reveal that the cytochrome c oxidase proteins Cox13-HA and Cox5a-HA and the cytochrome bc1 protein, Cor1, interact with Cox15. A, blots of SDS-polyacrylamide gels following co-immunoprecipitation of Cox15-Myc from mitochondria isolated from WT strains (containing the indicated tags). For the blots probing native proteins, a strain containing only COX15::MYC was used. Total, Unbound, and Elutions are as follows: for blots probed for Cox15-Myc, <0.1 μg mitochondria loaded on gel (Total), 0.05% of the unbound fraction loaded on gel (Unbound), and 33% of total elution (Elutions); for blots probed for HA-tagged proteins, 40–100 μg of mitochondria (Total), 2.5–5% of unbound fraction (Unbound), and 33% of total elution (Elutions); for blots probed for native Cor1, 5 μg of mitochondria (Total), 0.5% of unbound fraction (Unbound), and 33% of elution (Elutions); for blots probed for native Cbp4 and Oxa1, 85 μg (Cbp4) and 20 μg (Oxa1) of mitochondria (Total), 5% of the unbound fraction (Unbound), and 33% of total elution (Elutions). All co-IP experiments were performed two times (biological replicates); Cor1 experiments were repeated in three biological replicates. B, co-IP experiments performed in either Δqcr8 or Δcox4 mitochondria containing the indicated tags. Co-IPs between Cox15-Myc and native Cor1 in both Δqcr8 and Δcox4 utilized a COX5A::HA strain. Gel loading was as in A. All experiments were performed in at least two biological replicates.

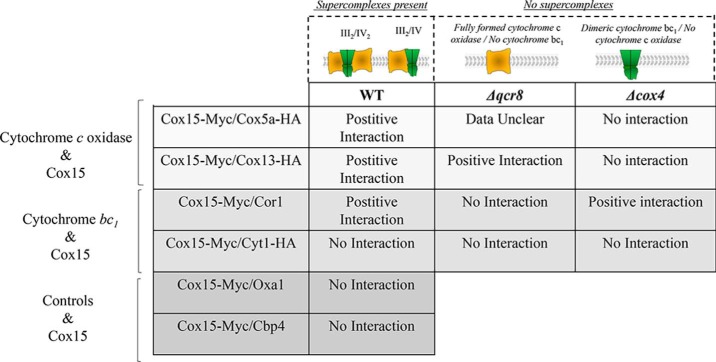

Table 1.

Summary of co-immunoprecipitation experiments

It should be noted that the co-immunoprecipitation of Cox15-Myc with Cox5a-HA, Cox13-HA, and Cor1 may represent either direct or indirect interactions. In other words, Cox15-Myc might physically interact with one or more of these proteins, or co-immunoprecipitation could be mediated through other proteins or complexes. Our data do not allow us to distinguish between these two types of interactions.

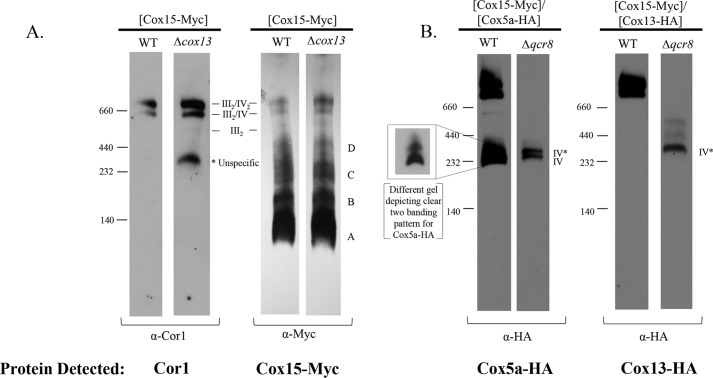

Cox15-Myc interacts with Cox13-HA from cytochrome c oxidase and Cor1 from the cytochrome bc1 complex in the absence of supercomplexes

Presumably the interactions between Cox15-Myc and Cox5a-HA, Cox13-HA, and Cor1 occur within respiratory supercomplexes. We next tested whether these interactions persist in the absence of supercomplexes. Our first approach was to follow the interaction of Cox15-Myc with the cytochrome c oxidase proteins, Cox5a-HA and Cox13-HA, using a Δqcr8 strain in which mature cytochrome bc1 fails to form yet cytochrome c oxidase is still present. This created a scenario in which cytochrome c oxidase exists in the absence of supercomplexes (Table 1). We found that Cox15-Myc still co-immunoprecipitates with Cox13-HA (Fig. 3B). Conversely, the interaction with Cox5a-HA is nearly abolished, although it is important to note that the total amount of Cox5a-HA present in Δqcr8 mitochondria appears to be reduced compared with WT mitochondria. Because only weak Cox5a-HA bands could be detected in the co-immunoprecipitation experiments using WT mitochondria (Fig. 3A), it is possible that weak bands observed in Fig. 3B are simply the result of a decrease in the total amount of Cox5a-HA in Δqcr8 mitochondria. Finally, in the absence of fully formed cytochrome c oxidase (Δcox4 strain), Cox15-Myc and Cox5a-HA do not interact, and the interaction between Cox15-Myc and Cox13-HA is also eliminated (Fig. 3B), indicating that intact cytochrome c oxidase is needed to maintain the Cox15–Cox13 interaction when supercomplexes are absent.

To probe further the relationship between Cox15 and Cor1, we tested whether Cox15-Myc interacts with Cor1 in the absence of fully assembled cytochrome c oxidase using a Δcox4 strain. Cox4, a nuclear encoded subunit of cytochrome c oxidase, assembles in an early intermediate complex with the Cox1 and Cox5a subunits (23–27). In its absence, this core complex does not form, and cytochrome c oxidase fails to assemble, yet cytochrome bc1 remains intact (Table 1). Surprisingly, Cox15 co-immunoprecipitates with Cor1 to the same extent in both WT and Δcox4 strains (Fig. 3B). Cox15-Myc and Cor1 do not interact in a Δqcr8 strain, however, indicating that intact cytochrome bc1 is required to maintain the Cox15-Cor1 interaction (Fig. 3B).

Where does Cox15-Myc interact with cytochrome c oxidase in the absence of supercomplexes?

Based on the robust interaction observed between Cox15-Myc and Cox13-HA, we hypothesized that some of the lower-molecular weight Cox15 complexes (bands A–D on BN-PAGE) may represent interactions with Cox13 in subassembly intermediates. Cox13 is one of the last subunits to be incorporated into cytochrome c oxidase, whereas Cox5a forms an early intermediate with Cox1 to which the rest of the subunits are added (24, 28–30). Perhaps Cox15 interacts with Cox13 and some other late-assembling intermediates away from the assembling core of cytochrome c oxidase. To address whether Cox15 forms specific interactions with Cox13, we probed the BN-PAGE distribution of Cox15-Myc complexes in a Δcox13 strain. Whereas Cox13 is necessary to maintain full cytochrome c oxidase function, it is not necessary for the stability of the rest of the enzyme complex, and its absence does not abolish supercomplex formation as marked by the presence of Cor1 within both supercomplexes (Fig. 4A) (27, 31). As shown in Fig. 4A, all Cox15-Myc complexes, including Cox15 within supercomplexes, are maintained in the absence of Cox13. This indicates that none of the lower Cox15-Myc complexes are solely represented by Cox13–Cox15 interactions and that Cox13 is not required to draw Cox15 into supercomplexes.

Figure 4.

Cox15 likely does not form significant interactions with Cox13 within assembly intermediates and in the absence of supercomplexes likely interacts with Cox13 either in IV* or the two complexes above IV*. A, BN-PAGE of Cor1 (10 μg of mitochondria loaded) and Cox15-Myc13 (20 μg of mitochondria loaded) within WT (COX15::MYC) or Δcox13/COX15::MYC strains probed with either anti Cor1 or anti-Myc antibodies. The band on the Cor1 blot at ∼440 kDa represents nonspecific binding of the anti-Cor1 antibody (see Fig. S2). B, BN-PAGE probing for Cox5a-HA complexes (40 μg of mitochondria) or Cox13-HA complexes (50 μg of mitochondria) in WT or Δqcr8 backgrounds. Cells used for experiments in A and B were grown in 2% galactose and 0.5% lactate YP medium. All experiments were performed two times (biological replicates).

Next, to better understand the differences we observed between the Cox15–Cox13 versus the Cox15–Cox5a interactions (Fig. 3B), we tested whether Cox13-HA and Cox5a-HA form distinct complexes from each other when Qcr8 is absent. In mitochondria from WT cells, Cox5a-HA is found mainly within both supercomplexes (III2/IV2 and III2/IV) and also in what appears to be the cytochrome c oxidase monomer (Fig. 4B). Depending on the resolution of the gel, the band representing the cytochrome c oxidase monomer can be observed as two distinct bands or one large band. This is consistent with previous reports that have identified two distinct forms of cytochrome c oxidase via BN-PAGE as marked by a slower-migrating complex (termed IV*) that is positioned directly above where monomeric cytochrome c oxidase would be expected (31, 32). As predicted, in the absence of Qcr8, Cox5a-HA appears to associate exclusively with what appears to be the two bands reflecting monomeric cytochrome c oxidase (Fig. 4B). In contrast, whereas Cox13-HA is only found within the two supercomplexes in WT mitochondria, when Qcr8 is absent, the predominate amount of Cox13 is in a complex that migrates in what appears to be the slower-migrating form of monomeric cytochrome c oxidase on BN-PAGE (IV*) as well as two less-abundant, higher-molecular weight complexes. Taking all of our data together, we conjecture that Cox15 interacts with Cox13-HA in these low-abundance intermediates that are independent of Cox5a, although we cannot rule out the possibility that Cox15 may also interact weakly with both Cox13 and Cox5a in the IV* form of monomeric cytochrome c oxidase.

Cox15-Myc interacts with Cor1 within the cytochrome bc1 dimer in the absence of supercomplexes

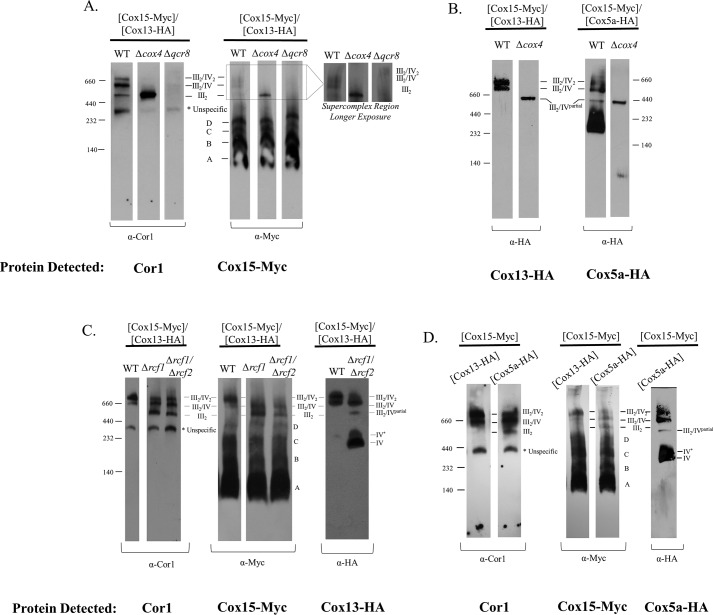

As discussed previously, Cox15-Myc interacts with Cor1 in the absence of supercomplexes only if cytochrome bc1 is fully formed (Fig. 3B), prompting us to investigate whether Cox15-Myc and Cor1 interact within the dimer of cytochrome bc1 when supercomplexes are absent. We observed the distribution of Cor1 and Cox15-Myc on BN-PAGE in a Δcox4 strain. As expected, BN-PAGE revealed that Cor1 was only present in the dimer of cytochrome bc1 (Fig. 5A), indicating that this is the only location in which Cox15-Myc could interact with Cor1 when Cox4 is absent. Indeed, when Cox15-Myc complexes are observed on BN-PAGE in a Δcox4 strain, a marked accumulation of Cox15 within an intermediate at the same molecular weight as the cytochrome bc1 dimer is observed (Fig. 5A). As expected, when Qcr8 is absent, Cor1 is no longer observed in the dimer of cytochrome bc1 because the cytochrome bc1 complex no longer forms. Likewise, Cox15 is no longer observed in the supercomplex region when Qcr8 is absent (Fig. 5A). Together, these data suggest that when the III2/IV2 and the III2/IV supercomplexes are absent, Cox15-Myc and Cor1 interact within the cytochrome bc1 dimer.

Figure 5.

BN-PAGE experiments reveal that Cox15-Myc13 is present in the cytochrome bc1 dimer when supercomplexes are destabilized. A, BN-PAGE of Cor1 (50 μg of mitochondria) and Cox15-Myc (10 μg of mitochondria). Strains used were COX15::MYC/COX13-HA, Δcox4/COX15::MYC/COX13HA, and Δqcr8/COX15::MYC/COX13HA. B, BN-PAGE of Cox13-HA (50 μg of mitochondria) and Cox5a-HA (40 μg of mitochondria). Strains used were COX15::MYC/COX13::HA and COX15::MYC/COX5a::HA (in both WT and Δcox4 backgrounds). C, BN-PAGE of Cor1 (50 μg of mitochondria), Cox15-Myc (10 μg of mitochondria), and Cox13-HA (50 μg of mitochondria) using a COX15::MYC/COX13::HA strain in WT, Δrcf1, or Δrcf1/Δrcf2 backgrounds. D, BN-PAGE probing for Cor1 (20 μg of mitochondria) or Cox15-Myc (10 μg of mitochondria) in either COX5A::HA/COX15::MYC or COX13::HA/COX15::MYC strains. The blot probing for Cox5a-HA (50 μg of mitochondria) utilizes the COX5A::HA/COX15::MYC strain. All strains represented in the entire figure were grown in 2% galactose, 0.5% lactate YP medium, and every BN-PAGE was performed 2–3 times (biological replicates). The bands at 440 kDa on the anti-Cor1 blots in A, C, and D represent nonspecific binding of the anti-Cor1 antibody (see Fig. S2).

Interestingly, we also noted that when Cox4 is absent under our experimental conditions, both Cox13-HA and Cox5a-HA were observed exclusively within an intermediate that also appeared to be the same molecular weight as the cytochrome bc1 dimer (Fig. 5B). This observation is consistent with the findings of others who report that subunits from cytochrome c oxidase can associate with the cytochrome bc1 dimer when cytochrome c oxidase assembly is stalled (24, 33). This intermediate was termed III2/IV* by Mick et al. (24) and is referred to as III2/IVpartial in this work, to avoid confusion with the IV* nomenclature used elsewhere. Therefore, it is possible that Cox15-Myc and Cor1 interact within a cytochrome bc1 dimer that has already associated with some cytochrome c oxidase subunits.

We tracked the presence of Cox15-Myc, Cor1, and Cox13-HA within the supercomplexes in Δrcf1 and Δrcf1/Δrcf2 strains. It is known that in the absence of respiratory supercomplex factor 1 (Rcf1), the distribution of the supercomplexes is altered such that the III2/IV2 supercomplex is diminished and a buildup of III2 is observed (31, 34, 35). In both Δrcf1 and Δrcf1/Δrcf2 strains, BN-PAGE probing for Cor1-containing complexes confirmed that the III2/IV2 supercomplex is diminished and that the cytochrome bc1 dimer accumulates (Fig. 5C). Cox15-Myc reflected that the trend observed for Cor1 in that Cox15-Myc was nearly absent in the III2/IV2 supercomplex but accumulated in a complex that appeared to be the dimer of cytochrome bc1 (Fig. 5C). When we probed for the distribution of Cox13-HA in a WT strain, we observed that Cox13-HA is only present in the III2/IV2 and III2/IV supercomplexes. In Δrcf1 and Δrcf1/Δrcf2 strains, however, the predominant amount of Cox13-HA is found not only within the two supercomplexes, but also as two bands migrating around 232 kDa. As discussed above, these two bands at 232 kDa likely reflect Cox13 within the two monomeric forms of cytochrome c oxidase. Finally, we do note a minor amount of Cox13 that appears to migrate at the same molecular weight as the likely III2/IVpartial complex, again suggesting that Cox15 and Cor1 may interact within a cytochrome bc1 dimer that is in association with some cytochrome c oxidase subunits. In sum, under conditions in which the cytochrome bc1 dimer is favored, as in the case of supercomplex destabilization from the loss of Rcf1 and Rcf1/Rcf2, we detect Cox15-Myc shifting its distribution from the III2/IV2 and III2/IV supercomplexes into what appears to be either the cytochrome bc1 dimer or the III2/IVpartial complex, whereas Cox13 shifts its distribution toward complexes IV and IV*.

In the course of our studies, we observed that in contrast to a Cox13-HA strain, a C-terminal HA tag on Cox5a causes a slight buildup of Cor1 within the cytochrome bc1 dimer without significant change to the abundance of Cor1 within the III2/IV2 or III2/IV supercomplexes (Fig. 5D). Intriguingly, Cox15-Myc again models the arrangement of Cor1 within supercomplexes. As observed with Cor1, Cox15-Myc is only present in the III2/IV2 or III2/IV supercomplexes in a Cox13-HA strain but displays a buildup within the cytochrome bc1 dimer when Cox5a has a C-terminal HA tag (Fig. 5D). When observing the distribution of Cox5a-HA from WT mitochondria, Cox5a-HA was predominately found within either the supercomplexes or the two forms of monomeric cytochrome c oxidase, with a trace amount also detected within the probable III2/IVpartial complex. As observed with the loss of Rcf1, when supercomplexes are destabilized due to a C-terminal HA tag on Cox5a, the distribution of Cox15-Myc is again shifted into the cytochrome bc1 dimer or the III2/IVpartial complex.

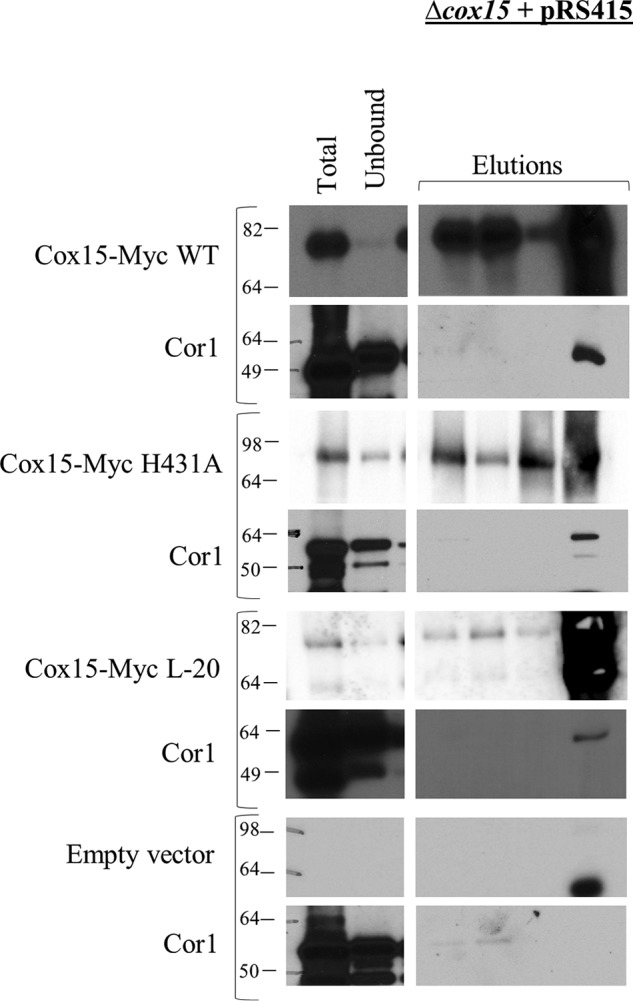

Cox15 maintains its interaction with Cor1 even when catalytically inactive and when unable to oligomerize

Finally, we wanted to ascertain whether the Cox15–Cor1 interaction required fully functioning Cox15. In the first experiment, we probed whether the interaction was maintained in a H431A amino acid variant of Cox15. His-431, one of the four strictly conserved His residues, is assumed to be located at one of the two heme-binding sites and has been shown previously to be required for activity (11). Both WT Cox15-Myc and mutant H431A Cox15-Myc were expressed individually from the pRS415 plasmid in Δcox15 S. cerevisiae (Table 2) at comparable steady-state levels (Fig. S3). Only WT Cox15-Myc was able to rescue respiratory competence (Fig. S3). The ability of native Cor1 to co-immunoprecipitate with the plasmid-borne enzymes was assessed. Both the plasmid-borne WT Cox15-Myc and H431A Cox15-Myc consistently co-immunoprecipitated with native Cor1 in the fourth elution, indicating that heme a is not required for the Cox15–Cor1 interaction (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study

| Genetic background/Description | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DY5113 | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, trp1−, his3− | W303a, WT |

| COX5A:HA, DY5113 | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP1+, his3−, COX5A::3HA | This study |

| COX13::HA, DY5113 | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP1+, his3−, COX13::3HA | This study |

| COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, trp1−, HIS3+, COX15::13MYC | Ref. 48 |

| COR1::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP1+, HIS3+, COR1::3HA, COX15::13MYC, | This study |

| CYT1::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP1+, HIS3+, CYT1–3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| COX5A::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP1+, HIS3+, COX5A::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| COX13::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP1+, HIS3+, COX13::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| SSA1::HA/COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, TRP+, HIS+, SSA1::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δqcr8, COX5A::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, TRP1+, HIS3+, qcr8::URA3, COX5A::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δqcr8, COX13::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, TRP1+, HIS+, qcr8::URA3, COX13::HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δcox4, COX5A::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, TRP1+, HIS3+, cox4::URA3, COX5A::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δcox4, COX13::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, TRP1+, HIS3+, cox4::URA3, COX13::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δcox13, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, trp1−, HIS+, cox13::URA3, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δrcf1, COX13::HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, TRP1+, HIS+, rcf1::URA3, COX13::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δrcf1, Δrcf2, | ||

| COX13-HA, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, TRP+, HIS+, rcf1::URA3, rcf2::kanMX6, COX5A::3HA, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δcor1, COX15::MYC | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, URA3+, trp1−, HIS+, cor1::URA3, COX15::13MYC | This study |

| Δcox15 | MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, trp1−, his3−, cox15::KanMX | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRS415 empty | Empty pRS415 vector | Ref. 8 |

| pRS415 COX15-Myc | COX15-13MYC with COX15 promoter and ADH1 terminator in pRS415 | Ref. 8 |

| pRS415 cox15-Myc H431A | cox15-13MYC H431A with COX15 promoter and ADH1 terminator in pRS415 | Ref. 8 |

| pRS415 cox15-Myc L-20 | cox15-13MYC L-20 (cox15-13MYC with 20 amino acids deleted from the linker between transmembrane helices IV and V) with COX15 promoter and ADH1 terminator in pRS415 | Ref. 8 |

Figure 6.

Blots of SDS-polyacrylamide gels following co-immunoprecipitation of WT Cox15-Myc13, H431A Cox15-Myc13, and L-20 Cox15-Myc13 with native Cor1. Each Cox15-Myc variant was expressed from pRS415 under the control of the native COX15 promoter in a Δcox15 strain. A control co-immunoprecipitation experiment using mitochondria from a Δcox15 strain carrying empty pRS415 is also shown. Due to the lower steady-state level of Cox15-Myc L-20, 1.5 mg of mitochondria from this strain was used for co-immunoprecipitation experiments instead of 1 mg. Total, Unbound, and Elutions are as follows: for blots probed for Cox15-Myc, <0.5 μg of mitochondria loaded on gel (Total), 0.05% of the unbound fraction loaded on gel (Unbound), and 33% of total elution (Elutions); for blots probed for native Cor1, 5 μg of mitochondria (Total), 0.5% of unbound fraction (Unbound), and 33% of elution (Elutions). All experiments were performed 2–4 times (biological replicates).

Next, we investigated whether the Cox15–Cor1 interaction is maintained when Cox15 is unable to form homooligomers. Recently, Swenson et al. (8) identified a 20-amino acid deletion mutant of Cox15 (L-20 variant) that maintained close to normal steady-state levels but was unable to oligomerize. We expressed the L-20 Cox15-Myc deletion mutant from the pRS415 plasmid (Table 2) in a Δcox15 strain, and we assessed whether plasmid-borne L-20 Cox15-Myc was able to interact with native Cor1. The plasmid-borne L-20 Cox15-Myc exhibited lower steady-state levels than observed for plasmid-borne WT Cox15-Myc or H431A Cox15-Myc (Fig. S3). Interestingly, however, the Cox15–Cor1 interaction was maintained in the L-20 Cox15-Myc mutant, despite the reduction in steady-state levels for L-20 Cox15-Myc (Fig. 6). Together, these data indicate that the ability of Cox15 to interact either directly or indirectly with Cor1 and the cytochrome bc1 dimer does not depend on either the presence of heme a or the oligomeric state of Cox15.

Discussion

With the discovery of respiratory supercomplexes in S. cerevisiae by Cruciat et al. (22) and Schagger and Pfeiffer (21) in 2000, our knowledge of the electron transport chain has expanded. Since then, our understanding has continued to evolve as we learn that these supercomplexes likely do not solely represent the cytochrome bc1 and cytochrome c oxidase complexes, but potentially contain other regulators, assembly proteins, and transporter proteins. Among the proteins identified within respiratory supercomplexes in S. cerevisiae are the ADP/ATP carrier protein, AAC2 (36), the Tim23 inner membrane translocase complex (37–39), the mitochondrial cardiolipin transacylase, Taz1 (40), and the cytochrome c oxidase assembly factors Coa3, Shy1, and Cox14 (24, 41). In this report, we add an additional cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor to this list, heme a synthase (Cox15). Although only a small percentage of Cox15 is present in respiratory supercomplexes, this is consistent with the distribution of many other nonrespiratory complex proteins found to associate with supercomplexes (36–39). It has been speculated that different pools of respiratory supercomplexes may exist that vary with respect to the other interaction partners that associate with them (42, 43). It is possible that Cox15 also exists in a particular subset of respiratory supercomplexes, but more work is needed to address this question and, if so, determine whether Cox15 serves a particular purpose within that subset. Interestingly, whereas many of the nonrespiratory complex proteins reported to associate within supercomplexes are detected only under very mild solubilization conditions (0.5% digitonin) (36–39), the presence of Cox15 within respiratory supercomplexes is resistant to the harsher solubilization conditions used in this study (1% digitonin). This reflects a stable, albeit modest association with respiratory supercomplexes.

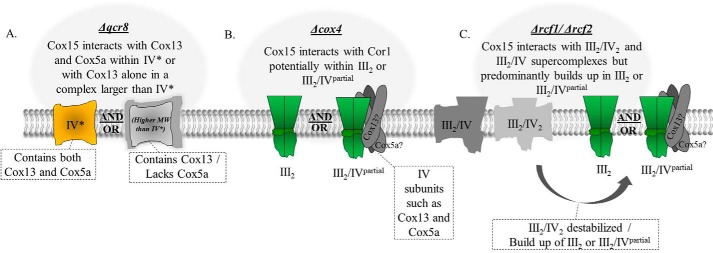

Given that Cox15 is present within respiratory supercomplexes, it is reasonable to expect Cox15 to co-purify with cytochrome c oxidase under nondenaturing conditions. Indeed, we detected an interaction between Cox15-Myc and both the Cox5a and Cox13 subunits of cytochrome c oxidase from WT mitochondria. Given that the only known function of Cox15 is to synthesize the heme a molecules that are utilized by cytochrome c oxidase, it is further reasonable to hypothesize that Cox15 should interact directly with monomeric forms of cytochrome c oxidase. To date, however, no significant interaction has been reported. Although Bareth et al. (10) reported that a sub-stoichiometric amount of Cox15 may associate with the early assembly intermediates that form with Cox1 and its assembly factors, there was no evidence that Cox15 formed stable interactions with fully assembled cytochrome c oxidase. Likewise, in this work, we were not able to detect strong evidence suggesting that Cox15 interacts with monomeric cytochrome c oxidase. We discovered that Cox15 interacts directly or indirectly with Cox13 and that these interactions persist when supercomplexes are unable to form (Δqcr8 mitochondria). Furthermore, we were unable to detect co-immunoprecipitation between Cox15 and Cox5a outside of supercomplexes, although the co-immunoprecipitating bands between Cox15 and Cox5a are weak even in the presence of supercomplexes. Therefore, although we cannot rule out the possibility that Cox15 interacts with Cox13 within the IV* form of monomeric cytochrome c oxidase, which contains Cox5a, we favor the conclusion that, in the absence of supercomplexes, Cox15 interacts with Cox13 in complexes lacking Cox5a that appear to be of a higher molecular weight than the IV* monomeric cytochrome c oxidase (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

The protein complexes in which Cox15 likely participates that were observed within the supercomplex region on BN-PAGE in Δqcr8, Δcox4, and Δrcf1/Δrcf2 mitochondria. In WT mitochondria, Cox15-Myc was found to associate within the III2/IV2 and III2/IV supercomplexes. A, in Δqcr8 mitochondria (cytochrome bc1 fails to assemble, but cytochrome c oxidase is present), Cox15 was found to interact with Cox13 from cytochrome c oxidase. Because we cannot exclude the possibility that Cox15 is capable of interacting with Cox5a in Δqcr8 mitochondria, the interaction with Cox13 in Δqcr8 mitochondria may occur either in the IV* form of monomeric cytochrome c oxidase or in complexes that are larger than monomeric cytochrome c oxidase, which contain Cox13 but lack Cox5a. B, in Δcox4 mitochondria, cytochrome c oxidase no longer assembles, but dimeric cytochrome bc1 still forms. Cox15 was found to maintain its interaction with Cor1 within the cytochrome bc1 dimer. The cytochrome bc1 dimer may be in association with cytochrome c oxidase subunits, such as Cox13 and Cox5a. C, in Δrcf1/Δrcf2 mitochondria, the III2/IV2 supercomplex is somewhat destabilized, and a buildup of the cytochrome bc1 dimer occurs. The association of Cox15 with the III2/IV2 supercomplex was also somewhat destabilized, and, like Cor1, Cox15 was found to associate with the cytochrome bc1 dimer, which may also be in association with some cytochrome c oxidase subunits.

In contrast, we detected a clear interaction between Cox15 and the cytochrome bc1 protein, Cor1. Not only does Cox15 interact either directly or indirectly with Cor1 in WT mitochondria (presumably within supercomplexes), but Cox15 also interacts with Cor1 in the absence of supercomplexes in Δcox4 mitochondria, presumably within the cytochrome bc1 dimer (Fig. 7B). Cox15 does not co-immunoprecipitate with Cor1 when cytochrome bc1 assembly is blocked (Δqcr8 mitochondria), implying that the two do not interact within Cor1 subassemblies of the bc1 complex. Co-immunoprecipitation between Cox15-Myc and Cor1 is also maintained in mutants of Cox15 that are unable to produce heme a or are unable to oligomerize. Interestingly, Rcf1 was also found to interact with Cor1 and other cytochrome bc1 proteins when cytochrome c oxidase assembly was stalled (34, 35). The significance of the interaction between Rcf1 and Cor1 is less resolved, however, as Rcf1 was not found to migrate within any high-molecular weight complexes in Δcox4 mitochondria (31). It has been hypothesized that perhaps Rcf1 acts as a bridge or a stabilizer between the cytochrome bc1 and cytochrome c oxidase complexes (34, 35), although this remains to be confirmed. The observation that some Cox15 migrates with the III2/IV2 and III2/IV supercomplexes in WT mitochondria as well as with the cytochrome bc1 dimer in Δcox4 mitochondria suggests a more stable direct or indirect interaction between Cox15 and Cor1.

We observed in this study that the cytochrome c oxidase proteins, Cox5a and Cox13, accumulate into what also appears to be the cytochrome bc1 dimer in Δcox4 mitochondria. Although there is some debate as to when assembling cytochrome c oxidase interacts with the cytochrome bc1 complex, it has been either shown or postulated that partially assembled complex IV is capable of interacting with complex III (24, 33). Likewise, it has also been demonstrated that partially assembled complex III can associate with complex IV (16, 33, 44). So, it is possible that what appears to be Cox5a and Cox13 within the cytochrome bc1 dimer in Δcox4 mitochondria may reflect partially assembled pools of cytochrome c oxidase subunits associating with already dimerized cytochrome bc1 (Fig. 7B). Mick et al. (24) reported the presence of a complex found in Δcox2 mitochondria, which they termed III2/IV* (and we refer to as III2/IVpartial), that migrates just above the cytochrome bc1 dimer on their blue native gels. This III2/IVpartial complex could be detected under steady-state conditions, and Shy1, Cyt1, and Cox4 were all found to be within this complex of partially assembled cytochrome c oxidase and dimerized cytochrome bc1. It is possible that the Cox15–Cor1 interaction that we detected in Δcox4 mitochondria occurs within the cytochrome bc1 dimer that reflects this III2/IVpartial complex (Fig. 7B). Although it could be argued that Cox15 may be drawn into the III2/IVpartial by Cox5a or Cox13, our co-immunoprecipitation experiments did not detect any interaction between Cox15 and either Cox5a or Cox13 in Δcox4 strains, whereas a strong interaction with Cor1 was identified (Fig. 3B). Additionally, our BN-PAGE data suggest that the Cox15 distribution within the supercomplexes more closely models Cor1 than either Cox5a or Cox13. This is most clearly observed in both Δrcf1 and Δrcf1/rcf2 mitochondria, where Cox15 was no longer observed in the upper III2/IV2 supercomplex but was shifted entirely into the III2/IV complex or cytochrome bc1 dimer (Fig. 5C). Therefore, based on the data presented in this study, it appears more likely that an interaction with Cor1 is mediating the association of Cox15 with either the cytochrome bc1 dimer or the III2/IVpartial complex.

Why would a protein whose only known function is to synthesize heme a for cytochrome c oxidase associate with Cor1 outside of supercomplexes? In fact, our data suggest that a portion of Cox15 is specifically conserved in the cytochrome bc1 dimer when supercomplex formation is compromised. In Δrcf1 and Cox5a-HA mitochondria, Cox15 associates within the cytochrome bc1 dimer even though the III2/IV2 and III2/IV supercomplexes are still present. Additionally, in Δcox4 mitochondria, it appears as if all of the supercomplex-bound Cox15 shifts to the dimer of bc1 rather than being absorbed back into the other lower-molecular weight Cox15 complexes. Perhaps when supercomplex formation is hindered, a pool of Cox15 is allocated to the bc1 dimer to remain positioned for hemylation of Cox1 within supercomplexes. To support this hypothesis, various studies have obtained results suggesting that cytochrome c oxidase is capable of being assembled within the supercomplexes (24, 25, 45, 46). If this is so, then perhaps Cox15 is needed for the hemylation of Cox1 as it is being incorporated into supercomplexes. Alternatively, recent reports have speculated that Cox15 may have an additional role within the cell in addition to the production of heme a for Cox1 due to the observations that Cox15 forms separate protein complexes from Cox10, the protein that functions immediately upstream in the heme a biosynthetic pathway, and that the Cox15 complexes form even in the absence of Cox1 or heme o (8, 10, 20, 47). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that Cox15 protein levels are 8–10 times higher than that of Cox10 (48). Further elucidating the reason why Cox15 remains associated with Cor1 in the cytochrome bc1 dimer, even in the absence of supercomplexes, may shed more light on a potential alternative function of Cox15 and may reveal the role that Cox15 serves within the respiratory supercomplexes.

In summary, we have found that not only does Cox15 associate within respiratory supercomplexes, it also is capable of interacting with Cor1 within the cytochrome bc1 dimer when supercomplex formation is compromised. Furthermore, whereas Cox15 and Cox13 also interact when supercomplex formation is compromised, the locations of these interactions were not as readily discernable as those between Cox15 and Cor1, thus highlighting a unique and unexpected relationship between Cox15 and the cytochrome bc1 complex.

Experimental procedures

Yeast strains and cloning

The S. cerevisiae strains described in this paper are derivatives of DY5113 (MATa, ade2−, can1−, leu2−, ura3−, trp1−, his−) and were generated within this strain or in a DY5113 strain containing COX15 with a genomic C-terminal Myc13 epitope (Table 2). All cloning was performed genomically by homologous recombination of gene-targeted PCR-amplified cassettes via the lithium acetate method of yeast transformation (49, 50). RCF2 and COX15 were deleted by replacement with the kanMX6 cassette from the pFA6a vector (51), and all other gene deletions were made by replacement with the URA3 cassette obtained from pBS1539 (Min-Hao Kuo, Michigan State University). C-terminal tagging of COR1, CYT1, COX5A, and COX13 utilized the 3× HA-TRP1 cassette from pFA6a (51).

All plasmids used in the Cox15 mutant studies were a kind gift from Dr. Oleh Khalimonchuk (University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE). The plasmids were expressed in a Δcox15 DY5113 background (Table 2).

Cell growth and mitochondrial isolation

Unless otherwise specified, yeast cultures were grown at 30 °C while shaking for 20 h in liquid YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone (tryptone), and 2% glucose). To enhance formation of III2/IV and III2/IV2 supercomplexes for better visualization in BN-PAGE experiments, yeast cultures were occasionally grown to mid-log phase in liquid medium containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% galactose, and 0.5% lactate (19, 21), as noted in the appropriate figure captions. For both WT and mutant Cox15-Myc expressed from the pRS415 plasmid, yeast cultures were grown in synthetic medium lacking leucine. Crude mitochondria were isolated as described previously (52, 53).

Respiratory competence

The respiration competency of the Δcox15 pRS415 strains was tested as described previously (8). Briefly, cells were grown in liquid synthetic medium (2% galactose, 0.1% glucose), normalized to an A600 of 0.3, and then serially diluted and spotted onto plates containing 2% glycerol and 2% lactate.

Blue native PAGE

BN-PAGE was performed as described previously (54). Briefly, mitochondria were solubilized for 15 min on ice in 10 μl of digitonin-containing buffer (20 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 0.1 mm EDTA, 50 mm NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 4 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1% (w/v) digitonin) per 10 μg of starting mitochondria. Solubilized mitochondrial proteins were clarified via centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min. Following centrifugation, 0.1 μl of sample buffer (5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, 500 mm 6-aminohexanoic acid, 0.1 mm BisTris (pH 7.0)) per 1 μg of starting mitochondria was added to the clarified supernatant. Samples were loaded on a 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad mini-PROTEAN-TGX system). Electrophoresis was conducted at 130 V for 6 h in cathode buffer containing 50 mm Tricine, 7.5 mm imidazole, 0.02 g of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (pH 7.0), and anode buffer containing 25 mm imidazole (pH 7.0). The gel was then electroblotted for 3 h at 60 V in buffer containing 50 mm Tricine and 7.5 mm imidazole (pH 7.0). Before immunodecoration, the membrane was washed in 100% methanol for 5 min to remove Coomassie dye and rinsed with Tris-buffered saline (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 27 mm KCl). For molecular weight estimation, the gel lane containing the ladder (GE Healthcare, catalog no. 17-0445-01) was excised, stained (2.5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue, 10% acetic acid, 25% methanol), and destained (10% acetic acid, 25% methanol). Swelling and shrinking of the gel slice during the staining and destaining procedure was accounted for when aligning with electroblotted protein complexes.

When analyzing the distribution of SDS-treated Cox15 on BN-PAGE, mitochondria were first solubilized with 1% SDS at 4 °C in buffer containing 50 mm NaCl, 50 mm imidazole, 5 mm 6-aminohexanoic acid, and Roche protease inhibitor. Following SDS solubilization, BN-PAGE was performed as described above.

2D blue native/SDS-PAGE of purified Cox15-Myc followed by MS

Mitochondria were prepared from 1.8 liters of S. cerevisiae containing C-terminal genomic Myc-tagged Cox15 (Cox15-Myc) grown in YPD (using tryptone as mentioned above). Mitochondria were solubilized for 2 h in 600 mm sorbitol, 20 mm HEPES, 4.1% digitonin, 150 mm NaCl, and Roche protease inhibitor in a 5-ml total volume. Solubilized mitochondrial proteins were clarified via centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min and added to 300 μl of anti-c-Myc resin (Sigma, A7470). Lysate and resin were incubated overnight at 4 °C, washed eight times with 1 ml of phosphate buffer (137 mm NaCl, 27 mm KCl, 100 mm Na2HPO4, 18 mm KH2PO4), and eluted in 10 1-ml fractions of PBS containing 0.1 mg/ml c-Myc peptide and 0.1% digitonin. Each elution fraction was incubated with resin for 5 min before collecting. Elution fractions containing Cox15-Myc were pooled and concentrated using an Amicon 10 MWCO membrane until the total volume was reduced to 80 μl. The buffer was exchanged by adding 500 mm 6-aminohexanoic acid and 200 mm NaCl to a final volume of 200 μl, centrifuging at 14,000 × g (4 °C) to a final volume of about 80 μl, and repeating. Following buffer exchange, the sample was adjusted to 150 μl, followed by the addition of 0.02% Ponceau and 10% glycerol (final concentrations). BN-PAGE was run as described previously. After BN-PAGE, a lane was excised and mounted to the top of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Following electrophoresis, the gel was silver-stained using the Proteosilver kit (Sigma). Protein bands of interest were excised, hydrolyzed by in-gel tryptic digest, and analyzed by MS (LC-MS/MS) as described previously (55).

BN-PAGE of Cox15-Myc complexes in the presence of cycloheximide

To analyze the presence of Cox15-Myc within supercomplexes following stalled nuclear translation, 250-ml cultures of SSA1::HA/COX15::MYC in YPD were started from 5-ml overnight cultures. The 250-ml cultures were allowed to grow for 20 h post-inoculation. Cycloheximide was then added to each culture (150 μg/ml), and cultures were harvested at various time points up to 24 h after cycloheximide addition. In previous unpublished work,3 we noted that the cytosolic heat shock protein, Ssa1, could be co-purified with our isolated crude mitochondria, so mitochondria were prepared as described above, and BN-PAGE was used to monitor the presence of Cox15-Myc within respiratory supercomplexes. SDS-PAGE of both Cox15-Myc and Ssa1-HA was used to monitor steady-state protein levels following cycloheximide addition.

Co-immunoprecipitation

For the anti-Myc co-immunoprecipitation experiments pulling down Cox15-Myc and probing for associated HA-tagged proteins, 1 mg of mitochondria was solubilized in 200 μl of buffer (4.1% digitonin (Sigma, D141), 150 mm NaCl, Roche Protease Inhibitor) for 2 h at 4 °C on a rocking platform. Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 9,600 × g to pellet unsolubilized material. Solubilized mitochondria were added to 25 μl of anti-Myc agarose (Sigma, A7470) and allowed to incubate overnight at 4 °C on a rocking platform. After collecting the unbound fraction, the anti-Myc resin was washed eight times with 1 ml of PBS. Protein was eluted by adding 30 μl of 2× SDS loading dye to the resin and rocking at 4 °C for 10 min, three times. A final elution was performed by boiling the resin for 5 min at 100 °C in 30 μl of 2× SDS loading dye.

Anti-Myc co-immunoprecipitation experiments pulling down Cox15-Myc that required the use of antibodies recognizing native Cor1 were performed as described above except an alternative anti-Myc agarose was used (Thermo, catalog no. 20168) due to cross-reactivity of the original agarose with the secondary antibodies at the same molecular weight as Cor1. Briefly, solubilized lysate was added to a 25-μl resin volume and incubated overnight at 4 °C on a rocking platform. The resin was washed six times with 500 μl of TBST (0.05% Tween 20), and the protein was eluted by adding three additions of 30 μl of 50 mm NaOH while rocking at room temperature. A final elution was collected by boiling the resin for 5 min with 30 μl of 2× SDS-PAGE buffer.

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments using WT and mutant Cox15-Myc expressed from the pRS415 plasmid were performed as described above for experiments using native Cor1. Due to a decrease in L-20 Cox15-Myc steady-state levels, however, 1.5 mg of mitochondria was used for co-immunoprecipitation.

For all co-immunoprecipitation experiments, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Control co-immunoprecipitation experiments were conducted in strains in which Cox15 was untagged to ensure that the positive interactions observed were not artifacts.

Immunodetection

The commercially available primary antibodies utilized in these studies were anti Myc (Thermo, catalog no. R950-25; lot 1827713), anti-HA (Thermo, catalog no. 26183), and anti-porin (Thermo, catalog no. 459500). Primary antibodies that recognized native proteins were a kind gift from Dr. Martin Ott (Stockholm University). All primary antibodies were validated as described in the legend to Fig. S1. The secondary antibody utilized following the anti-Myc, anti-HA, and anti-porin antibodies was goat anti mouse (Pierce, catalog no. 31430; lot PF202430). For the blots probing native proteins, the goat anti rabbit (Abcam, catalog no. 6721; lot GR169100-2) antibody was used. Supersignal West Pico (Thermo, catalog no. 34080) was used following SDS-PAGE to visualize blotted proteins on PVDF membranes. Following BN-PAGE of Cox15-Myc, a homemade chemiluminescent solution (Solution A: 100 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.5), 2.5 mm luminol, 0.4 mm p-coumeric acid; Solution B: 100 mm Tris (pH 8.5), 0.06% of 30% H2O2) was used for visualizing protein bands on PVDF membranes. All blots were exposed to HyBlot autoradiography film or imaged with a Chemi-Doc MP imager (Bio-Rad).

Author contributions

E. J. H. and E. L. H. designed the study and wrote the paper. E. D. R. prepared Fig. 2, performed replicate experiments for data presented in Figs. 3 and 4B, performed control experiments for the Cor1 antibody, and performed the studies on mutant Cox15 presented in Fig. 6. A. J. W. performed experiments for and prepared Fig. 1 (A and C) and also performed many background experiments leading up to this work. E. J. H. performed all other experiments and prepared the rest of the figures. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dennis Winge (University of Utah) and Dr. Oleh Khalimonchuk (University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE) for BN-PAGE instruction, reagents, and helpful discussion. Additionally, Dr. Oleh Khalimonchuck provided the pRS415 plasmids containing WT Cox15-Myc, the L-20 Cox15-Myc construct, and the H431A Cox15-Myc mutant studied in this work (8). We also thank Dr. Martin Ott (Stockholm University) for the Cor1, Cbp4, and Oxa1 antiserum (56, 57) and also helpful discussion.

This work was supported in full by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM101386. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3.

E. J. Herwaldt, A. J. White, and E. L. Hegg, unpublished observations.

- BN-PAGE

- blue native PAGE

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- PVDF

- polyvinylidene difluoride

- 2D

- two-dimensional

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- IP

- immunoprecipitation.

References

- 1. Gennis R., and Ferguson-Miller S. (1995) Structure of cytochrome c oxidase, energy generator of aerobic life. Science 269, 1063–1064 10.1126/science.7652553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Timón-Gómez A., Nývltová E., Abriata L. A., Vila A. J., Hosler J., and Barrientos A. (2018) Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis: recent developments. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 76, 163–178 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zee J. M., and Glerum D. M. (2006) Defects in cytochrome oxidase assembly in humans: lessons from yeast. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84, 859–869 10.1139/o06-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fontanesi F., Soto I. C., Horn D., and Barrientos A. (2006) Assembly of mitochondrial cytochrome c-oxidase, a complicated and highly regulated cellular process. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C1129–C1147 10.1152/ajpcell.00233.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim H. J., Khalimonchuk O., Smith P. M., and Winge D. R. (2012) Structure, function, and assembly of heme centers in mitochondrial respiratory complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1604–1616 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shoubridge E. A. (2001) Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Am. J. Med. Genet. 106, 46–52 10.1002/ajmg.1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khalimonchuk O., Bestwick M., Meunier B., Watts T. C., and Winge D. R. (2010) Formation of the redox cofactor centers during Cox1 maturation in yeast cytochrome oxidase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1004–1017 10.1128/MCB.00640-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swenson S., Cannon A., Harris N. J., Taylor N. G., Fox J. L., and Khalimonchuk O. (2016) Analysis of oligomerization properties of heme a synthase provides insights into its function in eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 10411–10425 10.1074/jbc.M115.707539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor N. G., Swenson S., Harris N. J., Germany E. M., Fox J. L., and Khalimonchuk O. (2017) The assembly factor Pet117 couples heme a synthase activity to cytochrome oxidase assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 1815–1825 10.1074/jbc.M116.766980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bareth B., Dennerlein S., Mick D. U., Nikolov M., Urlaub H., and Rehling P. (2013) The heme a synthase Cox15 associates with cytochrome c oxidase assembly intermediates during Cox1 maturation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 4128–4137 10.1128/MCB.00747-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hederstedt L. (2012) Heme a biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 920–927 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown K. R., Brown B. M., Hoagland E., Mayne C. L., and Hegg E. L. (2004) Heme a synthase does not incorporate molecular oxygen into the formyl group of heme a. Biochemistry 43, 8616–8624 10.1021/bi049056m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhuang J., Reddi A. R., Wang Z., Khodaverdian B., Hegg E. L., and Gibney B. R. (2006) Evaluating the roles of the heme a side chains in cytochrome c oxidase using designed heme proteins. Biochemistry 45, 12530–12538 10.1021/bi060565t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soto I. C., Fontanesi F., Liu J., and Barrientos A. (2012) Biogenesis and assembly of eukaryotic cytochrome c oxidase catalytic core. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 883–897 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bundschuh F. A., Hannappel A., Anderka O., and Ludwig B. (2009) Surf1, associated with Leigh syndrome in humans, is a heme-binding protein in bacterial oxidase biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25735–25741 10.1074/jbc.M109.040295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zara V., Conte L., and Trumpower B. L. (2007) Identification and characterization of cytochrome bc1 subcomplexes in mitochondria from yeast with single and double deletions of genes encoding cytochrome bc1 subunits. FEBS J. 274, 4526–4539 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khalimonchuk O., Bird A., and Winge D. R. (2007) Evidence for a pro-oxidant intermediate in the assembly of cytochrome oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17442–17449 10.1074/jbc.M702379200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pierrel F., Khalimonchuk O., Cobine P. A., Bestwick M., and Winge D. R. (2008) Coa2 is an assembly factor for yeast cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis that facilitates the maturation of Cox1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 4927–4939 10.1128/MCB.00057-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stuart R. A. (2009) Chapter 11 Supercomplex organization of the yeast respiratory chain complexes and the ADP/ATP carrier proteins. Methods Enzymol. 456, 191–208 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04411-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khalimonchuk O., Kim H., Watts T., Perez-Martinez X., and Winge D. R. (2012) Oligomerization of heme o synthase in cytochrome oxidase biogenesis is mediated by cytochrome oxidase assembly factor Coa2. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26715–26726 10.1074/jbc.M112.377200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schägger H., and Pfeiffer K. (2000) Supercomplexes in the respiratory chains of yeast and mammalian mitochondria. EMBO J. 19, 1777–1783 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cruciat C. M., Brunner S., Baumann F., Neupert W., and Stuart R. A. (2000) The cytochrome bc1 and cytochrome c oxidase complexes associate to form a single supracomplex in yeast mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18093–18098 10.1074/jbc.M001901200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nijtmans L. G., Artal Sanz M., Bucko M., Farhoud M. H., Feenstra M., Hakkaart G. A., Zeviani M., and Grivell L. A. (2001) Shy1p occurs in a high molecular weight complex and is required for efficient assembly of cytochrome c oxidase in yeast. FEBS Lett. 498, 46–51 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02447-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mick D. U., Wagner K., van der Laan M., Frazier A. E., Perschil I., Pawlas M., Meyer H. E., Warscheid B., and Rehling P. (2007) Shy1 couples Cox1 translational regulation to cytochrome c oxidase assembly. EMBO J. 26, 4347–4358 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lazarou M., Smith S. M., Thorburn D. R., Ryan M. T., and McKenzie M. (2009) Assembly of nuclear DNA-encoded subunits into mitochondrial complex IV, and their preferential integration into supercomplex forms in patient mitochondria. FEBS J. 276, 6701–6713 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07384.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowhan W., Bibus C. R., and Schatz G. (1985) The cytoplasmically-made subunit IV is necessary for assembly of cytochrome c oxidase in yeast. EMBO J. 4, 179–184 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb02334.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taanman J. W., and Capaldi R. A. (1993) Subunit VIa of yeast cytochrome c oxidase is not necessary for assembly of the enzyme complex but modulates the enzyme activity: isolation and characterization of the nuclear-coded gene. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18754–18761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nijtmans L. G., Taanman J. W., Muijsers A. O., Speijer D., and Van den Bogert C. (1998) Assembly of cytochrome-c oxidase in cultured human cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 254, 389–394 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fontanesi F., Jin C., Tzagoloff A., and Barrientos A. (2008) Transcriptional activators HAP/NF-Y rescue a cytochrome c oxidase defect in yeast and human cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 775–788 10.1093/hmg/ddm349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barrientos A., Gouget K., Horn D., Soto I. C., and Fontanesi F. (2009) Suppression mechanisms of COX assembly defects in yeast and human: insights into the COX assembly process. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 97–107 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vukotic M., Oeljeklaus S., Wiese S., Vögtle F. N., Meisinger C., Meyer H. E., Zieseniss A., Katschinski D. M., Jans D. C., Jakobs S., Warscheid B., Rehling P., and Deckers M. (2012) Rcf1 mediates cytochrome oxidase assembly and respirasome formation, revealing heterogeneity of the enzyme complex. Cell Metab. 15, 336–347 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Levchenko M., Wuttke J. M., Römpler K., Schmidt B., Neifer K., Juris L., Wissel M., Rehling P., and Deckers M. (2016) Cox26 is a novel stoichiometric subunit of the yeast cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 1624–1632 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cui T. Z., Conte A., Fox J. L., Zara V., and Winge D. R. (2014) Modulation of the respiratory supercomplexes in yeast: enhanced formation of cytochrome oxidase increases the stability and abundance of respiratory supercomplexes. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 6133–6141 10.1074/jbc.M113.523688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y. C., Taylor E. B., Dephoure N., Heo J. M., Tonhato A., Papandreou I., Nath N., Denko N. C., Gygi S. P., and Rutter J. (2012) Identification of a protein mediating respiratory supercomplex stability. Cell. Metab. 15, 348–360 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Strogolova V., Furness A., Robb-McGrath M., Garlich J., and Stuart R. A. (2012) Rcf1 and Rcf2, members of the hypoxia-induced gene 1 protein family, are critical components of the mitochondrial cytochrome bc1-cytochrome c oxidase supercomplex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 1363–1373 10.1128/MCB.06369-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dienhart M. K., and Stuart R. A. (2008) The yeast Aac2 protein exists in physical association with the cytochrome bc1-COX supercomplex and the TIM23 machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3934–3943 10.1091/mbc.e08-04-0402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van der Laan M., Wiedemann N., Mick D. U., Guiard B., Rehling P., and Pfanner N. (2006) A role for Tim21 in membrane-potential-dependent preprotein sorting in mitochondria. Curr. Biol. 16, 2271–2276 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saddar S., Dienhart M. K., and Stuart R. A. (2008) The F1F0-ATP synthase complex influences the assembly state of the cytochrome bc1-cytochrome oxidase supercomplex and its association with the TIM23 machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6677–6686 10.1074/jbc.M708440200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiedemann N., van der Laan M., Hutu D. P., Rehling P., and Pfanner N. (2007) Sorting switch of mitochondrial presequence translocase involves coupling of motor module to respiratory chain. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1115–1122 10.1083/jcb.200709087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Claypool S. M., Boontheung P., McCaffery J. M., Loo J. A., and Koehler C. M. (2008) The cardiolipin transacylase, tafazzin, associates with two distinct respiratory components providing insight into Barth syndrome. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5143–5155 10.1091/mbc.e08-09-0896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mick D. U., Vukotic M., Piechura H., Meyer H. E., Warscheid B., Deckers M., and Rehling P. (2010) Coa3 and Cox14 are essential for negative feedback regulation of COX1 translation in mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 191, 141–154 10.1083/jcb.201007026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stuart R. A. (2008) Supercomplex organization of the oxidative phosphorylation enzymes in yeast mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 411–417 10.1007/s10863-008-9168-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vogel F., Bornhövd C., Neupert W., and Reichert A. S. (2006) Dynamic subcompartmentalization of the mitochondrial inner membrane. J. Cell Biol. 175, 237–247 10.1083/jcb.200605138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Conte A., Papa B., Ferramosca A., and Zara V. (2015) The dimerization of the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex is an early event and is independent of Rip1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1853, 987–995 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brandner K., Mick D. U., Frazier A. E., Taylor R. D., Meisinger C., and Rehling P. (2005) Taz1, an outer mitochondrial membrane protein, affects stability and assembly of inner membrane protein complexes: implications for Barth Syndrome. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5202–5214 10.1091/mbc.e05-03-0256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bianchi C., Genova M. L., Parenti Castelli G., and Lenaz G. (2004) The mitochondrial respiratory chain is partially organized in a supercomplex assembly: kinetic evidence using flux control analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36562–36569 10.1074/jbc.M405135200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bestwick M., Khalimonchuk O., Pierrel F., and Winge D. R. (2010) The role of Coa2 in hemylation of yeast Cox1 revealed by its genetic interaction with Cox10. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 172–185 10.1128/MCB.00869-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Z., Wang Y., and Hegg E. L. (2009) Regulation of the heme a biosynthetic pathway: differential regulation of heme a synthase and heme o synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 839–847 10.1074/jbc.M804167200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Longtine M. S., McKenzie A. 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., and Pringle J. R. (1998) Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953–961 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10%3C953::AID-YEA293%3E3.0.CO%3B2-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gietz R. D., and Schiestl R. H. (2007) High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat. Protoc. 2, 31–34 10.1038/nprot.2007.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bähler J., Wu J. Q., Longtine M. S., Shah N. G., McKenzie A. 3rd, Steever A. B., Wach A., Philippsen P., and Pringle J. R. (1998) Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14, 943–951 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10%3C943::AID-YEA292%3E3.0.CO%3B2-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lange H., Kispal G., and Lill R. (1999) Mechanism of iron transport to the site of heme synthesis inside yeast mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18989–18996 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Diekert K., de Kroon A. I., Kispal G., and Lill R. (2001) Isolation and subfractionation of mitochondria from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Cell. Biol. 65, 37–51 10.1016/S0091-679X(01)65003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frazier A. E., Chacinska A., Truscott K. N., Guiard B., Pfanner N., and Rehling P. (2003) Mitochondria use different mechanisms for transport of multispanning membrane proteins through the intermembrane space. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7818–7828 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7818-7828.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., and Mann M. (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68, 850–858 10.1021/ac950914h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hildenbeutel M., Hegg E. L., Stephan K., Gruschke S., Meunier B., and Ott M. (2014) Assembly factors monitor sequential hemylation of cytochrome b to regulate mitochondrial translation. J. Cell Biol. 205, 511–524 10.1083/jcb.201401009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hildenbeutel M., Theis M., Geier M., Haferkamp I., Neuhaus H. E., Herrmann J. M., and Ott M. (2012) The membrane insertase Oxa1 is required for efficient import of carrier proteins into mitochondria. J. Mol. Biol. 423, 590–599 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Solmaz S. R. N., and Hunte C. (2008) Structure of complex III with bound cytochrome c in reduced state and definition of a minimal core interface for electron transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17542–17549 10.1074/jbc.M710126200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Maréchal A., Meunier B., Lee D., Orengo C., and Rich P. R. (2012) Yeast cytochrome c oxidase: a model system to study mitochondrial forms of the haem-copper oxidase superfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 620–628 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.