The lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) become chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa that is difficult to eradicate by antibiotic treatment. Two key P. aeruginosa antibiotic resistance mechanisms are the AmpC β-lactamase that degrades β-lactam antibiotics and MexXYOprM, a three-protein efflux pump that expels aminoglycoside antibiotics from the bacterial cells.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotic resistance, cystic fibrosis, gene expression, beta-lactamase, efflux pump, efflux pumps

ABSTRACT

The lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF) become chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa that is difficult to eradicate by antibiotic treatment. Two key P. aeruginosa antibiotic resistance mechanisms are the AmpC β-lactamase that degrades β-lactam antibiotics and MexXYOprM, a three-protein efflux pump that expels aminoglycoside antibiotics from the bacterial cells. Levels of antibiotic resistance gene expression are likely to be a key factor in antibiotic resistance but have not been determined during infection. The aims of this research were to investigate the expression of the ampC and mexX genes during infection in patients with CF and in bacteria isolated from the same patients and grown under laboratory conditions. P. aeruginosa isolates from 36 CF patients were grown in laboratory culture and gene expression measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The expression of ampC varied over 20,000-fold and that of mexX over 2,000-fold between isolates. The median expression levels of both genes were increased by the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. To measure P. aeruginosa gene expression during infection, we carried out RT-qPCR using RNA extracted from fresh sputum samples obtained from 31 patients. The expression of ampC varied over 4,000-fold, while mexX expression varied over 100-fold, between patients. Despite these wide variations, median levels of expression of ampC in bacteria in sputum were similar to those in laboratory-grown bacteria. The expression of mexX was higher in sputum than in laboratory-grown bacteria. Overall, our data demonstrate that genes that contribute to antibiotic resistance can be highly expressed in patients, but there is extensive isolate-to-isolate and patient-to-patient variation.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infects the lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF), with infections lasting for years or decades (1–3). Chronic P. aeruginosa infections in patients with CF are associated with progressive clinical decline and increased morbidity, leading to respiratory failure and premature death (4–6). Aggressive antibiotic treatment can eliminate P. aeruginosa from the lower airways during the initial stage of infection (1, 3). However, once chronic infection becomes established, existing antibiotic treatment regimens usually fail to eradicate infection, although they reduce the bacterial burden (7, 8). Treatment differs between patients and between CF care centers but typically involves the use of one or more aminoglycosides, such as tobramycin; a carbapenem, including meropenem; a fluoroquinolone, such as ciprofloxacin; and in some cases, colistin, a polymyxin (9, 10). P. aeruginosa undergoes genetic changes during the course of chronic infection that help it adapt to the CF airway microenvironment, including mutations associated with increased antibiotic resistance (11, 12). CF is characterized by periods of clinical stability interspersed with pulmonary exacerbations that are associated with reduced pulmonary lung function and require hospitalization, though the relationship between bacterial infection and exacerbation is unclear (1).

P. aeruginosa has multiple antibiotic resistance mechanisms (13–15). The expression of a number of these is induced by substrate antibiotics leading to increased resistance in a process known as adaptive resistance (13, 16–18). Two key antibiotic-inducible systems are AmpC β-lactamase, which confers resistance to members of the β-lactam class of antibiotics (14), and an efflux pump, MexXYOprM, that is associated with resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones, among other antibiotics (19, 20). β-Lactam antibiotics increase expression of the ampC gene, and aminoglycoside substrates increase expression of the mexXY genes, which are expressed as an operon (21). P. aeruginosa isolates cultured from individuals with CF commonly possess genetic mutations that give rise to increased ampC and mexXY expression and are associated with increased β-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotic resistance (22–31).

The physiology of P. aeruginosa growing in pure culture in laboratory medium is likely to be quite different from that in the CF airway where they exist in biofilms within the context of the infected host, with multiple other microbial species present (32, 33). These physiological differences may have profound effects on bacterial gene expression and antibiotic resistance (34, 35). However, there is limited information on the expression of antibiotic resistance genes as it occurs during infection. In a pioneering study, RNA was extracted from P. aeruginosa in samples of sputum from a single patient without any ex vivo incubation or laboratory culture of the bacteria in order to analyze bacterial gene expression in vivo in the patient (36). The expression of multiple genes, including ampC and the mexXY efflux genes, occurred at a much higher level during infection in the patient than in bacteria isolated from the patient and grown under laboratory conditions.

The overall aims of this study were to measure the expression of ampC and mexX antibiotic resistance genes during infection in CF, and to determine how gene expression during infection relates to expression and antibiotic resistance of bacteria in laboratory culture.

RESULTS

Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in P. aeruginosa in sputum from patients with CF.

Expectorated sputum was obtained from 36 patients with CF and P. aeruginosa infection of different ages (range, 11 to 58 years; median age, 24 years) attending four different CF centers (Dunedin, Hobart, and two independent hospitals in Brisbane). Patient demographics are listed in Table 1. Two of the patients were transiently infected with P. aeruginosa, with the remainder of the patients being chronically infected.

TABLE 1.

Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa used in this study

| Isolatea | Source and/or description | Patient sexb | Patient age (yr) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with cystic fibrosis | ||||

| 001C | Dunedin | M | 51 | This study |

| 002C | Dunedin | M | 25 | This study |

| 003B | Dunedin | F | 36 | This study |

| 004 | Dunedin | M | 20 | This study |

| 005A | Dunedin | M | 28 | This study |

| 009B | Dunedin | M | 30 | This study |

| 012-4 | Dunedin | F | 24 | This study |

| 012-2 | Dunedin | F | 24 | This study |

| 014-2A | Dunedin | M | 43 | This study |

| 015A | Dunedin | F | 28 | This study |

| 021-3A | Dunedin | M | 23 | This study |

| 030-1 | Dunedin | M | 58 | This study |

| 036-1 | Dunedin | F | 31 | This study |

| 039-1 | Dunedin | M | 22 | This study |

| 284 | Tasmania | F | 20 | This study |

| 451 | Tasmania | F | 23 | This study |

| 310A | Tasmania | F | 26 | This study |

| 454A | Tasmania | M | 24 | This study |

| 399 | Tasmania | F | 28 | This study |

| 254 | Tasmania | M | 50 | This study |

| 409 | Tasmania | F | 22 | This study |

| 001-A1 | Brisbane | F | 16 | This study |

| 002-A2 | Brisbane | F | 11 | This study |

| 003-A1 | Brisbane | F | 11 | This study |

| 006-A2 | Brisbane | F | 15 | This study |

| 007-A1 | Brisbane | M | 16 | This study |

| 008-A1 | Brisbane | F | 12 | This study |

| 403-102 | Brisbane | F | 22 | This study |

| 403-110 | Brisbane | F | 22 | This study |

| 403-103 | Brisbane | M | 38 | This study |

| 403-104 | Brisbane | M | 28 | This study |

| 403-105 | Brisbane | F | 19 | This study |

| 403-106 | Brisbane | F | 36 | This study |

| 403-107 | Brisbane | F | 26 | This study |

| 403-108 | Brisbane | F | 23 | This study |

| 403-109 | Brisbane | M | 21 | This study |

| CF07 | Melbourne | M | 5 | 54 |

| CF13 | Auckland | M | 5 | 54 |

| CF21 | Sydney | M | 2 | 54 |

| CF23 | Sydney | F | 2 | 54 |

| Non-cystic fibrosis strains | ||||

| PAO1 | Melbourne; wound isolate | 55 | ||

| PW8616 | PAO1 with transposon insertion phoAwp06q2E07 in ampD gene | 56 | ||

| PW4501 | PAO1 with transposon insertion lacZbp01q1C12 in mexZ gene | 56 | ||

| ATCC 25873 | USA; blood culture | 57 | ||

| Pa4 | Belgium; urinary tract infection | 58 | ||

| Pa5 | Belgium; intensive care unit | 58 | ||

| Pa6 | Belgium; urinary tract infection | 58 |

Matching sputum samples were available for all CF isolates except CF07-CF23. All CF isolates were from chronically infected patients, except for 002-A2, 003-A1, and CF07-CF23.

M, male; F, female.

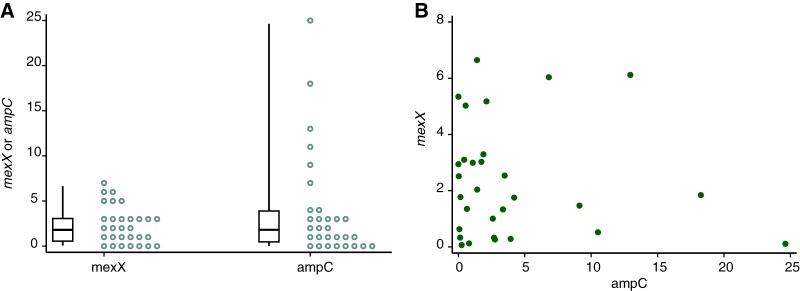

The expression of ampC and mexX antibiotic resistance genes was measured by extracting RNA from expectorated sputum and then carrying out RT-qPCR. Gene expression was quantified for 31 of the 36 samples analyzed, with the remaining samples either giving no detectable expression of the P. aeruginosa genes tested (2 samples) or showing expression at a level that was too low for quantification (3 samples; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Among the quantifiable samples, the expression of ampC varied over 4,000-fold (range, 0.004 to 24.6; median, 1.74; 25th to 75th percentiles, 0.34 to 3.71, relative to the reference genes), while mexX expression varied by approximately 100-fold (range, 0066 to 6.65; median, 1.77; 25th to 75th percentiles 0.426 to 3.06) (Fig. 1A and Table S1). There was no evidence of correlation between the expression of ampC and the expression of mexX (P = 0.559) (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these data indicate that both ampC and mexX are expressed during CF airway infection, but there is very marked variation in the expression of these genes across sputum samples from different patients.

FIG 1.

Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in P. aeruginosa in sputum. Expression of ampC and mexX was measured in 31 sputum samples from patients with cystic fibrosis. (A) The individual expression levels of ampC and mexX (circles), as well as boxplots showing medians, 25th and 75th percentiles, and minimum and maximum values, are shown. (B) Comparison of expression of ampC and mexX. Expression of ampC and mexX for each sample is shown.

Correlations between resistances to different antibiotics.

At the same time that samples were collected for analysis of gene expression, P. aeruginosa was isolated from sputum samples. We first investigated whether MICs for different antibiotics were correlated. MICs were determined for 6 antibiotics for isolates from 28 patients. The antibiotics selected represented three commonly used classes of anti-Pseudomonas antibiotics used in the treatment of CF, comprising β-lactams (aztreonam, ceftazidime, meropenem, and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid [Timentin]), an aminoglycoside (tobramycin), and a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin). MICs are shown in Table S1. Using the EUCAST breakpoints (37), 21% of the strains were resistant to aztreonam, 32% were resistant to ceftazidime, 63% were resistant to meropenem, 25% were resistant to ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, 40% were resistant to tobramycin, and 25% were resistant to ciprofloxacin. Four isolates showed resistance to all six agents, and a further three strains were sensitive to only one antibiotic.

Correlation analysis was carried out to test the hypothesis that there is a correlation between levels of resistance to different antibiotics (Table 2). There was a strong correlation between MICs for the four β-lactam antibiotics aztreonam, ceftazidime, meropenem, and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid (Spearman's correlation coefficients = 0.74 to 0.93, P < 0.001 in all cases). There was also a significant, though lower, correlation between MICs for antibiotics from different classes. For example, resistance to meropenem correlated with resistance to tobramycin (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.63, P < 0.001), as well as with resistance to ciprofloxacin (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.60, P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Correlations between antibiotic MICsa

| Antibiotic | Aztreonam | Ceftazidime | Meropenem | Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid | Ciprofloxacin | Tobramycin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aztreonam | 1.00 | |||||

| Ceftazidime | 0.84 (<0.001) | 1.00 | ||||

| Meropenem | 0.80 (<0.001) | 0.91 (<0.001) | 1.00 | |||

| Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid | 0.88 (<0.001) | 0.82 (<0.001) | 0.74 (<0.001) | 1.00 | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.35 (0.0646) | 0.55 (0.0026) | 0.60 (0.0008) | 0.36 (0.0806) | 1.00 | |

| Tobramycin | 0.40 (0.0334) | 0.44 (0.0202) | 0.63 (<0.001) | 0.25 (0.2309) | 0.58 (0.0030) | 1.0000 |

MICs were measured for 28 isolates of P. aeruginosa from CF patients (Table S1), and Spearman's correlation coefficients for pairs of antibiotics are shown. P values for correlations between values are shown in parentheses. Correlation analysis between MICs of meropenem and tobramycin included data for an additional 11 isolates (Table S1).

The same antibiotics were examined for their ability to induce the expression of ampC and mexX in P. aeruginosa reference strain PAO1. Meropenem was the strongest inducer of ampC expression (8.6-fold), and tobramycin was the strongest inducer of mexX expression (6.5-fold) (Fig. S1A).

Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in laboratory-grown bacteria.

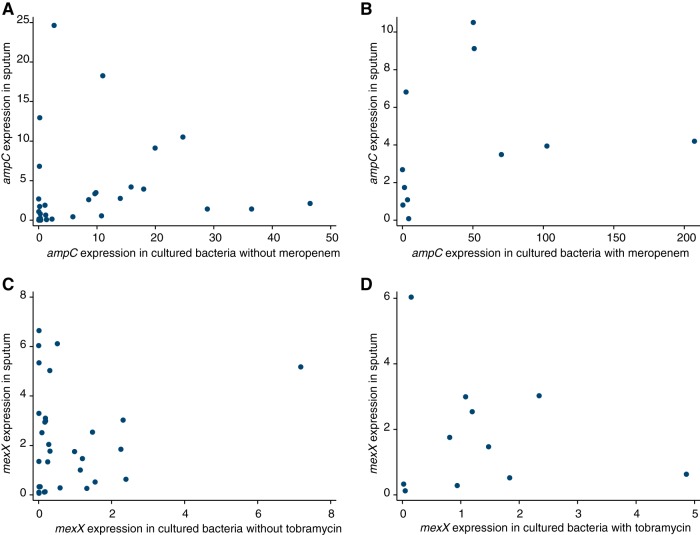

We also measured the in vitro expression of ampC and mexX among P. aeruginosa isolates cultured from sputum and grown on laboratory agar in both the presence and absence of two antimicrobial agents. The results are listed in Table S1 and summarized in Fig. 2. In the absence of antibiotics, the expression of ampC varied over 20,000-fold between isolates (range, 0.002 to 46.5; median, 1.28; 25th to 75th percentiles, 0.178 to 10.9). There was less variation in the expression of mexX (range, 0.004 to 7.18; median, 0.189; 25th to 75th percentiles, 0.019 to 1.09), but nonetheless, there was a 2,000-fold difference in the expression of mexX between the lowest- and highest-expressing strains. The median expression values for the five non-CF strains were lower (0.121 for ampC and 0.011 for mexX) than for the CF strains. Mutations in ampD or mexZ, which are known regulators of ampC and mexX, respectively (14, 38), resulted in increased ampC and mexX gene expression in the reference strain PAO1, as expected (Fig. S1B). There was a correlation between the expression of ampC and mexX for the isolates of P. aeruginosa from CF patients (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.51, P = 0.002) (Fig. 2C). This is consistent with the strong correlation between resistance to tobramycin and to meropenem (Table 2).

FIG 2.

Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in laboratory-grown bacteria. Expression of ampC and mexX was determined for 36 isolates of P. aeruginosa from different CF patients cultured in the absence of antibiotic and for 14 isolates cultured in the presence of sub-MICs of antibiotic. The individual expression of ampC and mexX (circles), as well as boxplots showing medians, 25th and 75th percentiles, and minimum and maximum values, are shown. (A) ampC. Median expression of 0.82 (absence of meropenem) and 4.06 (presence of meropenem). (B) mexX. Median expression of 0.79 (absence of tobramycin) and 1.01 (presence of tobramycin). (C) Comparison of expression of ampC and mexX in the absence of antibiotics.

β-Lactam antibiotics increase the expression of ampC, and aminoglycoside substrates increase expression of the mexXY genes (21). To determine whether this was also the case for isolates in our study, gene expression was also measured for a subset of 14 isolates from CF patients grown with sub-MICs of meropenem or tobramycin (Fig. 2A and B). The presence of meropenem increased ampC expression by, on average, 5-fold across the 14 isolates (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.001). There was also a strong intrastrain correlation between gene expression with and without meropenem (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.78, P < 0.001) (Fig. S2A). Likewise, the presence of tobramycin increased the expression of mexX by, on average, 1.3-fold (P = 0.048). The intrastrain correlation between gene expression with and without added tobramycin was very strong (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.90, P < 0.001) (Fig. S2B).

The expression of ampC and mexX was tested for correlation with the MIC of each strain for meropenem and tobramycin, respectively. The expression of ampC was correlated with the MIC for meropenem (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.49, P = 0.003 for bacteria grown in the absence of meropenem) (Fig. S3A), with the correlation being stronger for bacteria grown in the presence of meropenem (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.61, P = 0.020) (Fig. S3B). These findings are consistent with those of previous studies indicating that the expression of ampC is correlated with β-lactam resistance (22, 30, 39–41), although meropenem is usually not a good substrate for AmpC β-lactamase (42). It remains to be determined whether ampC gene expression in our samples correlates more strongly with resistance to antibiotics that are better substrates for the enzyme. The expression of mexX did not correlate with the MIC for tobramycin when the bacteria were grown in the absence of antibiotic (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.19, P = 0.287) (Fig. S3C) but had a non-statistically significant tendency when the bacteria were grown in the presence of tobramycin (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.51, P = 0.065) (Fig. S3D). A number of studies have demonstrated that the MexXYOprM efflux pump contributes to aminoglycoside resistance (reviewed in reference 38); for example, the tobramycin MIC of mutants of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 lacking mexXY is 4-fold (43) or at least 8-fold (44) lower than that of isogenic mexXY-containing bacteria. However, resistance to tobramycin is multifactorial (14, 21), and a recent study indicates that some isolates of P. aeruginosa with high expression of the mexXYoprM efflux pump are nonetheless susceptible to tobramycin (45). It is likely that the effects of differences in the expression of mexX on tobramycin resistance are masked by other resistance mechanisms for the isolates of P. aeruginosa examined in this study.

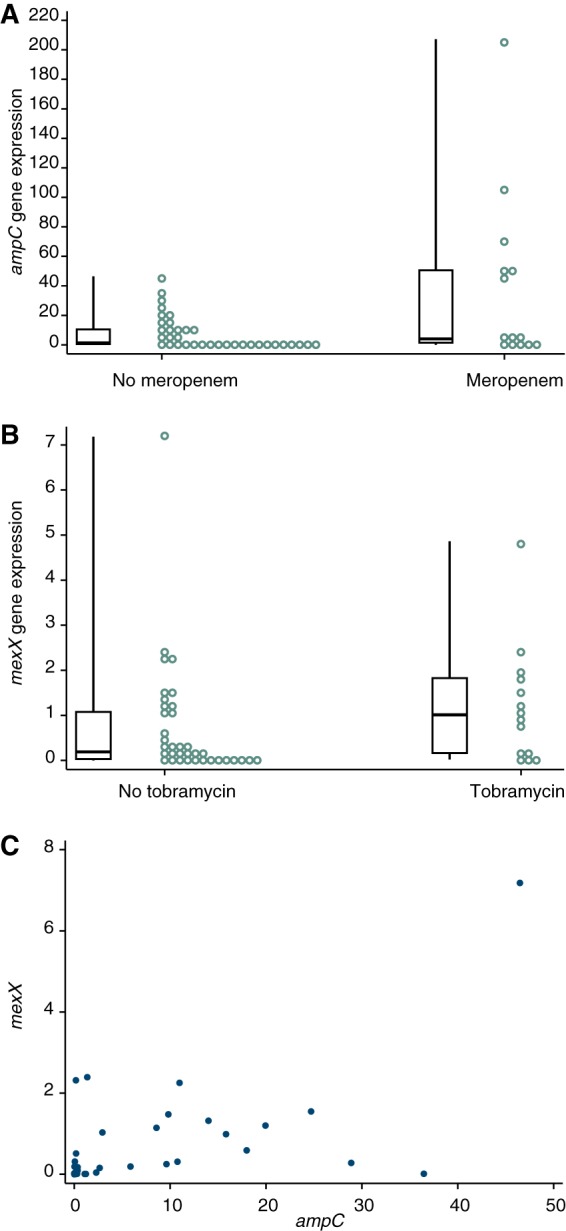

Relationship between resistance gene expression in sputum and laboratory-grown bacteria.

The expression of ampC was lower in bacteria in the sputum samples than for the corresponding bacteria grown on laboratory agar without antibiotic or in the presence of meropenem, but the difference was not statistically significant (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.052 and 0.062, respectively). However, there was some correlation between the expression of ampC in sputum samples and the expression of ampC by the corresponding P. aeruginosa isolates grown without antibiotics (Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.37, P = 0.046) (Fig. 3A). These findings indicate a degree of relationship between gene expression in sputum and expression in the corresponding bacteria grown in culture, although the different physiology of P. aeruginosa during infection may involve lower expression of ampC. The expression of ampC in sputum samples was not significantly correlated with the expression of ampC in bacteria grown on meropenem-containing agar (Rho = 0.464, P = 0.151).

FIG 3.

Comparison of antibiotic resistance gene expression in bacteria in sputum and in cultured bacteria. (A) Expression of ampC in cultured bacteria grown in the absence of meropenem was correlated with expression in the corresponding sputum sample (n = 31, Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.367, P = 0.046). (B) Expression of ampC in cultured bacteria grown in the presence of meropenem was not correlated with expression in the corresponding sputum sample (n = 11, Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.464, P = 0.151). (C) Expression of mexX in cultured bacteria grown in the absence of tobramycin was not correlated with expression in the corresponding sputum sample (n = 31, Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.007, P = 0.973). (D) Expression of mexX in cultured bacteria grown in the presence of tobramycin was not correlated with expression in the corresponding sputum sample (n = 11, Spearman's correlation coefficient = 0.264, P = 0.433).

Conversely, the expression of mexX was higher in sputum samples than when the corresponding bacteria were grown in the laboratory without antibiotics (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.002). It was also higher than for bacteria grown on agar containing tobramycin, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.328). The expression of mexX in bacteria in sputum did not correlate with expression of mexX by the corresponding P. aeruginosa grown on agar (Fig. 3C and D, Spearman's correlation coefficient, P = 0.811 and 0.433).

Gene expression of bacteria in sputum was also compared with the MICs of the corresponding P. aeruginosa isolates. There was no significant correlation between the expression of ampC in sputum and the MIC of isolated bacteria for meropenem (Spearman's correlation coefficient, P = 0.252), nor between the expression of mexX in sputum and the MICs of isolated bacteria for tobramycin (Spearman's correlation coefficient, P = 0.116).

DISCUSSION

In this research, we investigated the expression of two key P. aeruginosa antibiotic resistance genes, ampC and mexX, during infection in CF. Samples from patients at four different hospitals (three different cities) and with a wide range of ages were analyzed to represent a diversity of CF patients. Both ampC and mexX were expressed during infection, but there was a remarkably wide range of expression of both genes. The wide range of gene expression extended to bacteria isolated from sputum and grown in laboratory culture. In pairwise comparisons, the expression of ampC in bacteria in sputum was not significantly different from that in laboratory-grown bacteria; the expression of mexX was slightly higher in sputum than for bacteria grown on laboratory agar.

There was high variation in the expression of both ampC (over 20,000-fold) and mexX (2,000-fold) among isolates of P. aeruginosa grown on laboratory agar. Other researchers have also reported extensive variation in the expression of these genes among isolates of P. aeruginosa from a number of clinical settings (25, 27, 30, 39–41), reflecting the frequent occurrence of mutations that result in upregulation of ampC and mexX in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa (22–31).

Meropenem increased the expression of ampC, and tobramycin increased expression of mexX in the isolates in our study. These findings are consistent with antibiotic-inducible expression of ampC and mexX in the type strain P. aeruginosa PAO1 (14, 38), although to the best of our knowledge, the effects of sub-MIC amounts of antibiotics on the expression of ampC and mexX in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa have not been examined previously. There was also a correlation between the expression of ampC and that of mexX for the laboratory-grown bacteria. ampC and mexX are not known to share a regulatory mechanism. It is plausible that prolonged exposure to antibiotics during chronic CF infection selects for independently arising mutations that cause higher expression of the ampC and mexX genes.

This possibility is consistent with the strong correlation between resistances to different antibiotics (β-lactams, an aminoglycoside, and a fluoroquinolone) for the isolates tested, both within and between antibiotic classes (Table 2), something that has been observed previously (46, 47). Correlation, especially between different classes of antibiotics, could reflect patient treatment with prolonged administration of multiple antibiotics selecting for mutants with increased resistance to different antibiotic classes due to multiple independent resistance mechanisms. However, a correlation between resistance to different antibiotics may also result from shared resistance mechanisms, such as reduced access of multiple β-lactams to P. aeruginosa (14, 30), or enhanced activity of efflux pumps that export multiple antibiotics, including different antibiotic classes (14).

The expression of antibiotic resistance genes in sputum samples varied over 4,000-fold for ampC and approximately 100-fold for mexX. The occurrence of sputum samples with low levels of expression of ampC and/or mexX indicates that at least under some circumstances, even low levels of transcription are sufficient to allow survival in CF. The wide variation in gene expression in P. aeruginosa in laboratory culture indicates that strain-to-strain variation is at least part of the cause for the range of gene expression in sputum samples. The expression of ampC was similar in bacteria in sputum to that in bacteria grown in laboratory medium, and there was a modest correlation between ampC expression levels in the two environments. Conversely, the expression of mexX was higher in bacteria in sputum, and expression in laboratory culture did not show evidence of correlation with expression in sputum. These differences most likely reflect at least in part the difference in physiological states of P. aeruginosa bacteria in the two different environments. For example, gene expression may be affected by different growth rates of bacteria in the CF lung and in laboratory culture, by growth in complex biofilms during infection, by the presence of other bacteria, and by oxidative stress due to the action of the immune system. Gene expression in sputum could also be affected by changes in the lung environment during infection, such as the transition between stable infection and exacerbation, and, as antibiotics influence gene expression, differences in the antibiotic treatment received by each patient prior to sample collection. Furthermore, data from each sputum sample represent the average of the infecting P. aeruginosa population, which can have considerable genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity (11). The individual isolates tested in laboratory culture may therefore not be representative of the infecting population. Further research analyzing multiple samples and isolates from individual patients and determining whether there is a correlation between patient treatment or clinical status and resistance gene expression will be required to distinguish these possibilities.

Overall, our findings demonstrate a remarkably wide range of P. aeruginosa antibiotic resistance gene expression during infection in CF patients and between isolates of the bacteria. The reasons for this high patient-to-patient variability, which may influence the effectiveness of treatment, remain to be determined. The presence of antibiotics increased the expression of resistance genes of clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa in vitro and will be important to determine the extent to which antibiotic treatment affects resistance gene expression in infections. The differences in expression of ampC and mexX during infection and in laboratory-grown bacteria emphasize the different physiology of P. aeruginosa in the two environments and the importance of investigating the physiology of P. aeruginosa within the human host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and sampling.

Sputum samples were collected under the approval of the Southern Tasmanian Health and Medical Research Ethics Committee (H9813), the Queensland Children's Health Services (RCH) Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/11/QRCH/163), the Metro North Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee of The Prince Charles Hospital (HREC/08/QPCH/87), and the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committees (NTY/10/12/106). Written informed consent was obtained for all study participants. Individuals with CF were recruited from outpatient clinics and inpatients being treated for pulmonary exacerbations. P. aeruginosa was isolated from samples of sputum using cetrimide agar (Oxoid) or by growth on nonselective agar followed by confirmatory PCR testing, as described previously (48). For isolation of RNA, sputum was expectorated directly into RNAlater (Qiagen) and stored at 4°C. A total of 36 sputum samples for RNA analysis were collected from CF patients in Dunedin (New Zealand), Brisbane (Queensland, Australia), and Hobart (Tasmania, Australia) (Table 1). Patients were 83% adults, with an age range of 11 to 58 years and median age of 24 years (interquartile range, 21 to 28 years). All of these patients except for three (those with isolates 002-A2, 003-A1, and 030-1) were chronically infected with P. aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa was analyzed from a further four samples from CF patients for which sputum for RNA analysis was unavailable. Five reference strains of P. aeruginosa from non-CF infections (Table 1) were included for comparison in some analyses. Expectorated sputum was obtained from 36 patients attending four different CF centers (Dunedin, Hobart, and two independent hospitals in Brisbane).

Antibiotic sensitivity testing.

Antibiotic sensitivity testing was carried out using the protocol of Weigand et al. (49). Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa grown in King's B broth (50) were diluted to approximately 106 CFU/ml, and 5-μl portions were inoculated as spots onto plates of Mueller-Hinton agar (Becton Dickinson) containing doubling dilutions of antibiotic. After the spots had dried, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The MIC was defined through visual examination as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that inhibited the growth of the bacteria.

RT-qPCR.

RNA was extracted from sputum samples that had been collected into RNAlater, as described previously (51). RNA was also extracted from bacteria that had been spread onto Mueller-Hinton agar, supplemented as required with meropenem or tobramycin (one-third of the MIC), and incubated overnight at 37°C. Bacteria were collected into 1 ml of a 2:1 mixture of RNAprotect (Qiagen) and King's B broth. Following centrifugation, the bacterial cell pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer containing lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature to lyse the bacteria. RNA was then extracted as described above.

Aliquots of RNA were reverse transcribed to make cDNA, and transcripts were quantified by RT-qPCR, as described previously (51, 52). Gene-specific primers for P. aeruginosa ampC (5′-TCG CCT GAA GGC ACT GGT-3′ and 5′-GGT GGC GGT GAA GGT CTT G-3′), mexX (5′-GGC CCT GGT CGC CCT ATT C-3′ and 5′-TCC TCG TAC AGG CGA CGG-3′), and the reference genes clpX and oprL, established previously (51, 52), were used. The use of reference genes corrected for differences in bacterial load across different samples. There was a very strong correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient [R2] = 0.91) between the crossing point (Cp) values obtained with clpX and oprL with the sputum samples used in this study. Primer amplification efficiencies were determined using serial dilutions of genomic DNA templates from the reference strain PAO1 and the clinical isolates DUN002C, DUN005A, 002-A2, and 403-110; these were between 1.8 and 2.0 for all primer pairs with all templates. Quantitative PCR was carried out using SYBR green I master mix in conjunction with the LightCycler 480 platform (Roche). All reactions were carried out in duplicate. The presence of correct products was confirmed by melt curve analysis and by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the amplification efficiencies of each reaction were confirmed using LinRegPCR (53). The expression of antibiotic resistance genes was calculated relative to the geometric mean of clpX and oprL using the LightCycler software (51).

Statistical analyses.

Pairs of outcomes were examined for evidence of monotonic associations using Spearman's correlation coefficients (i.e., for values of one outcome showing a positive or negative, but not necessarily linear, association against the other outcome). Levels of expression were compared between pairs of outcomes within study participants using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests to determine if within-participant differences tended to be positive or negative. For these analyses, only participants with both outcomes measured were able to be included. Analyses were performed using Stata 15.1, and a two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all cases. Some outcomes were unavailable for some participants, and all available data were used for each particular analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by research grants to I.L.L. and B.B. from the New Zealand Lotteries Board (Health), CureKids, Cystic Fibrosis New Zealand Shares in Life Fund, the HS & JC Anderson Trust, and the New Zealand Health Research Council.

We are very grateful to Jan Cowan, Joyce Cheney, and Daniel Smith for their assistance in collecting samples for this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01789-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Langan KM, Kotsimbos T, Peleg AY. 2015. Managing Pseudomonas aeruginosa respiratory infections in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 28:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2002. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talwalkar JS, Murray TS. 2016. The approach to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Clin Chest Med 37:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emerson J, Rosenfeld M, McNamara S, Ramsey B, Gibson RL. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 34:91–100. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nixon GM, Armstrong DS, Carzino R, Carlin JB, Olinsky A, Robertson CF, Grimwood K. 2001. Clinical outcome after early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 138:699–704. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.112897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Kosorok MR, Farrell PM, Laxova A, West SE, Green CG, Collins J, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML. 2005. Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA 293:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. 2003. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168:918–951. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkby S, Novak K, McCoy K. 2009. Update on antibiotics for infection control in cystic fibrosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 7:967–980. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remmington T, Jahnke N, Harkensee C. 2016. Oral anti-pseudomonal antibiotics for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD005405. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005405.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith DJ, Ramsay KA, Yerkovich ST, Reid DW, Wainwright CE, Grimwood K, Bell SC, Kidd TJ. 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic resistance in Australian cystic fibrosis centres. Respirology 21:329–337. doi: 10.1111/resp.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winstanley C, O'Brien S, Brockhurst MA. 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa evolutionary adaptation and diversification in cystic fibrosis chronic lung infections. Trends Microbiol 24:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marvig RL, Sommer LM, Molin S, Johansen HK. 2015. Convergent evolution and adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within patients with cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet 47:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ng.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breidenstein EB, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Hancock RE. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol 19:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. 2009. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:582–610. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole K. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front Microbiol 2:65. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández L, Breidenstein EB, Hancock RE. 2011. Creeping baselines and adaptive resistance to antibiotics. Drug Resist Updat 14:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daikos GL, Jackson GG, Lolans VT, Livermore DM. 1990. Adaptive resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics from first-exposure down-regulation. J Infect Dis 162:414–420. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daikos GL, Lolans VT, Jackson GG. 1991. First-exposure adaptive resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics in vivo with meaning for optimal clinical use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35:117–123. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Nishino T. 2000. Substrate specificities of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:3322–3327. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.12.3322-3327.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li XZ, Plesiat P, Nikaido H. 2015. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:337–418. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita Y, Tomida J, Kawamura Y. 2014. Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antimicrobials. Front Microbiol 4:422. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juan C, Macia MD, Gutierrez O, Vidal C, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of beta-lactam resistance mediated by AmpC hyperproduction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4733–4738. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4733-4738.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bratu S, Landman D, Gupta J, Quale J. 2007. Role of AmpD, OprF and penicillin-binding proteins in beta-lactam resistance in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol 56:809–814. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamorano L, Moya B, Juan C, Oliver A. 2010. Differential beta-lactam resistance response driven by ampD or dacB (PBP4) inactivation in genetically diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1540–1542. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prickett MH, Hauser AR, McColley SA, Cullina J, Potter E, Powers C, Jain M. 2017. Aminoglycoside resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis results from convergent evolution in the mexZ gene. Thorax 72:40–47. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guénard S, Muller C, Monlezun L, Benas P, Broutin I, Jeannot K, Plesiat P. 2014. Multiple mutations lead to MexXY-OprM-dependent aminoglycoside resistance in clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:221–228. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01252-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam S, Oh H, Jalal S, Karpati F, Ciofu O, Hoiby N, Wretlind B. 2009. Chromosomal mechanisms of aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 15:60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogne C, Aires JR, Bailly C, Hocquet D, Plesiat P. 2004. Role of the multidrug efflux system MexXY in the emergence of moderate resistance to aminoglycosides among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1676–1680. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1676-1680.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vettoretti L, Plesiat P, Muller C, El Garch F, Phan G, Attree I, Ducruix A, Llanes C. 2009. Efflux unbalance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:1987–1997. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01024-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomás M, Doumith M, Warner M, Turton JF, Beceiro A, Bou G, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Efflux pumps, OprD porin, AmpC beta-lactamase, and multiresistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2219–2224. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00816-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López-Causapé C, Sommer LM, Cabot G, Rubio R, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Johansen HK, Figuerola J, Canton R, Kidd TJ, Molin S, Oliver A. 2017. Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutational resistome in an international cystic fibrosis clone. Sci Rep 7:5555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05621-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filkins LM, O'Toole GA. 2015. Cystic fibrosis lung infections: polymicrobial, complex, and hard to treat. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Høiby N, Ciofu O, Bjarnsholt T. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in cystic fibrosis. Future Microbiol 5:1663–1674. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. 2010. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waite RD, Paccanaro A, Papakonstantinopoulou A, Hurst JM, Saqi M, Littler E, Curtis MA. 2006. Clustering of Pseudomonas aeruginosa transcriptomes from planktonic cultures, developing and mature biofilms reveals distinct expression profiles. BMC Genomics 7:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Son MS, Matthews WJ Jr, Kang Y, Nguyen DT, Hoang TT. 2007. In vivo evidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nutrient acquisition and pathogenesis in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun 75:5313–5324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01807-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2013. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, version 3.1. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Växjö, Sweden: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/Breakpoint_table_v_3.1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita Y, Tomida J, Kawamura Y. 2012. MexXY multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol 3:408. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quale J, Bratu S, Gupta J, Landman D. 2006. Interplay of efflux system, ampC, and oprD expression in carbapenem resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1633–1641. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1633-1641.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castanheira M, Mills JC, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. 2014. Mutation-driven beta-lactam resistance mechanisms among contemporary ceftazidime-nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6844–6850. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03681-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabot G, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Tubau F, Macia MD, Rodriguez C, Moya B, Zamorano L, Suarez C, Pena C, Martinez-Martinez L, Oliver A, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI) . 2011. Overexpression of AmpC and efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from bloodstream infections: prevalence and impact on resistance in a Spanish multicenter study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1906–1911. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01645-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berrazeg M, Jeannot K, Ntsogo Enguene VY, Broutin I, Loeffert S, Fournier D, Plesiat P. 2015. Mutations in β-lactamase AmpC increase resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates to antipseudomonal cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6248–6255. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00825-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aires JR, Kohler T, Nikaido H, Plesiat P. 1999. Involvement of an active efflux system in the natural resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:2624–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Nishino T. 2000. Contribution of the MexX-MexY-oprM efflux system to intrinsic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:2242–2246. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.9.2242-2246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.López-Causapé C, Rubio R, Cabot G, Oliver A. 2018. Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa aminoglycoside mutational resistome in vitro and in the cystic fibrosis setting. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02583-. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02583-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mustafa MH, Chalhoub H, Denis O, Deplano A, Vergison A, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Tunney MM, Elborn JS, Kahl BC, Traore H, Vanderbist F, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2016. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients in northern Europe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:6735–6741. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01046-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jansen G, Mahrt N, Tueffers L, Barbosa C, Harjes M, Adolph G, Friedrichs A, Krenz-Weinreich A, Rosenstiel P, Schulenburg H. 2016. Association between clinical antibiotic resistance and susceptibility of Pseudomonas in the cystic fibrosis lung. Evol Med Public Health 2016:182–194. doi: 10.1093/emph/eow016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kidd TJ, Ramsay KA, Hu H, Bye PT, Elkins MR, Grimwood K, Harbour C, Marks GB, Nissen MD, Robinson PJ, Rose BR, Sloots TP, Wainwright CE, Bell SC, ACPinCF Investigators . 2009. Low rates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa misidentification in isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol 47:1503–1509. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. 2008. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc 3:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J Lab Med 44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konings AF, Martin LW, Sharples KJ, Roddam LF, Latham R, Reid DW, Lamont IL. 2013. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses multiple pathways to acquire iron during chronic infection in cystic fibrosis lungs. Infect Immun 81:2697–2704. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00418-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen AT, O'Neill MJ, Watts AM, Robson CL, Lamont IL, Wilks A, Oglesby-Sherrouse AG. 2014. Adaptation of iron homeostasis pathways by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine mutant in the cystic fibrosis lung. J Bacteriol 196:2265–2276. doi: 10.1128/JB.01491-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruijter JM, Ramakers C, Hoogaars WM, Karlen Y, Bakker O, van den Hoff MJ, Moorman AF. 2009. Amplification efficiency: linking baseline and bias in the analysis of quantitative PCR data. Nucleic Acids Res 37:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wainwright CE, Vidmar S, Armstrong DS, Byrnes CA, Carlin JB, Cheney J, Cooper PJ, Grimwood K, Moodie M, Robertson CF, Tiddens HA, ACFBAL Study Investigators . 2011. Effect of bronchoalveolar lavage-directed therapy on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and structural lung injury in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized trial. JAMA 306:163–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holloway B. 1955. Genetic recombination in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol 13:572–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, Will O, Kaul R, Raymond C, Levy R, Chun-Rong L, Guenthner D, Bovee D, Olson MV, Manoil C. 2003. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:14339–14344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Medeiros AA, O'Brien TF, Wacker WE, Yulug NF. 1971. Effect of salt concentration on the apparent in-vitro susceptibility of Pseudomonas and other Gram-negative bacilli to gentamicin. J Infect Dis 124(Suppl):S59–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meyer J-M, Stintzi A, De Vos D, Cornelis P, Tappe R, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H. 1997. Use of siderophores to type pseudomonads: the three Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine systems. Microbiology 143:35–43. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.