Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To examine the difference in the association between apolipoprotein (APO)E allele and overall and cardiovascular mortality between African Americans (AAs) and European Americans (EAs).

DESIGN:

Longitudinal, cohort study of 18 years.

SETTING:

Biracial urban US population sample.

PARTICIPANTS:

4,917, 68% AA and 32% EA.

MEASUREMENTS:

APOE genotype and mortality based on National Death Index.

RESULTS:

A higher proportion of AAs than of EAs had an APOE ε2 allele (ε2ε2/ε2ε3/ε2ε4; 22% vs 13%) and an APOE ε4 allele (ε3ε4/ε4ε4; 33% vs 24%). After adjusting for known risk factors, the risk of mortality was 19% less with the APOE ε2 allele (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.76–0.87), and the risk of cardiovascular mortality was 35% less (HR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.58–0.76) than with the ε3ε3 allele. The risk of mortality was 10% greater with the APOE ε4 allele (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.04–1.16), and the risk of cardiovascular mortality was 20% greater (HR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.07–1.29) than with the ε3ε3 allele. No difference in the association between APOE allele and mortality was observed between AAs and EAs.

CONCLUSION:

The APOE ε4 allele increased the risk of overall and cardiovascular mortality, whereas the APOE ε2 allele decreased the risk of overall and cardiovascular mortality. There was no racial difference in the association between these alleles and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:2425–2430, 2017.

The apolipoprotein (APO)E genotype has three common isoforms, with the APOE ε3 considered to be the “neutral” allele and the APOE ε2 and APOE ε4 alleles, with an amino acid substitution at 112 or 158, considered to be the “risk” alleles. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) used to identify the APOE risk alleles has been associated with longevity.1

The APOE ε4 alleles increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD),2,3 mortality,4,5 and cardiovascular disease, mostly ischemic heart disease,6 although the associations have been inconsistent for mortality7–9 or only in those with Down syndrome10 or at specific older ages.11 The other set of risk alleles, the APOE ε2, have shown associations with lower risk of AD12,13 and mortality,14 although it is not clear whether the APOE ε2 alleles may be protective for overall mortality15 by protecting against cardiovascular mortality.14 Most of the current literature is on older European Americans (EAs), with relatively little on African Americans (AAs).

The prevalence of APOE alleles varies considerably in various ethnic populations across various regions of the world6,16 and may also vary according to birth cohort.17 The APOE risk alleles in AAs is of considerable significance, because AAs have a higher prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease,18,19 a greater burden of cardiovascular disease,20 and higher rates of mortality in early old age.21 The allelic frequency of the APOE alleles in older AAs is not well established. For these reasons, we performed a study to examine the association between the APOE ε2 and APOE ε4 risk alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality in AAs and EAs. A second question of interest was whether the associations of the APOE ε2 and APOE ε4 alleles were age dependent.

METHODS

Study Design

The Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP) is a longitudinal, population-based epidemiological study of Alzheimer’s disease and other common health conditions in adults aged 65 and older conducted from 1993 to 2012.22 Starting in 1993, 78.7% of all residents aged 65 and older in a door-to-door census of a geographically defined, biracial Chicago community were enrolled in CHAP. From 2001, community residents who reached age 65 were also enrolled as successive cohorts. A total 10,802 participants enrolled in CHAP—6,158 as members of the original cohort and 4,644 as members of the successive age cohorts. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) samples were collected from 5,871 (54.4%) participants; 587 (5.4%) refused to provide DNA samples. Of the 5,871 participants, enough DNA was collected for 4,917 (83.7%) to be genotyped.

Population interviews were conducted in participants’ homes in approximately 3-year cycles. Data were collected for six cycles for the original cohort and for two to five cycles for the successive cohorts.23 Briefly, DNA samples were collected from a random sample of the population—approximately one-sixth of all participants who had a population interview and all participants from the last two cycles of data collection during their in-home interviews. Participants who were genotyped were approximately 1 year younger than the 5,885 who were not genotyped, had better global cognitive test scores (P < .001), and were more likely to be AA (68% vs 59%).

The Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study. All participants provided informed consent to be eligible to participate in this study.

Mortality Assessment

Ascertainment of mortality was completed through December 31, 2013. The primary source of death data was the Social Security Administration Death Master File (SSDMF), supplemented by field contacts with family and neighbors.24 In CHAP, 1,915 (39%) had died; 1,687 (88%) deaths were confirmed using the National Death Index (NDI Plus) and SSDMF. The remaining 228 (12%) participants died between January 1, 2011, and September 12, 2012, and are waiting confirmation from later versions of the NDI. Our secondary outcome, cardiovascular mortality, was based on death classifications in NDI (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) classification codes 390–459 or ICD-10 classification codes I00–I99). Cardiovascular mortality was available on 1,567 (93%) participants, who had death confirmed according to the NDI Plus report, of which 699 (45%) deaths could be attributed to cardiovascular mortality.

APOE Genotypes

APOE genotyping was performed at the Broad Institute using previously described methods25 and primers.26 The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs7412 and rs429358 were genotyped in each participant using the homogeneous Mass Extend MassARRAY platform (Sequenom). Genotyping success rate was 100% for SNP rs7412 and 99.8% for SNP rs429358. Both SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P = .08 and P = .79, respectively). The three common allelic variants were based on combinations of TT, CT, and CC alleles. Because the sample sizes for some of the risk alleles were small, we created two indicator variables for the presence of APOE ε2 alleles (ε22/ε23/ε24) and APOE ε4 alleles (ε34/ε44), with e33 serving as the reference allele.

Demographic and Health Measures

Our study also adjusted for several demographic (age, sex, race (AA, EA), and education (years of schooling completed)) and health variables. As potential health variables of interest, we also adjusted for baseline measures of body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) and systolic blood pressure (mmHg), assessed during the in-home interviews, and lifestyle measures, such as current and former smoking, current alcohol consumption (g/d), and hours of physical activity per week.

Global Cognitive Function

To adjust for cognitive status, we used a global cognitive test score based on two tests of episodic memory (immediate and delayed story recall) derived from the East Boston Test,27,28 a test of perceptual speed (the Symbol Digits Modalities Test),29 and a test of general orientation and global cognition (the Mini-Mental State Examination).30 These tests loaded on a single factor that accounted for approximately 75% of the variance,31 so we summed the short battery tests to their baseline mean and standard deviation to create a global cognitive test score. Our global cognitive test score is a strong marker of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.32

Statistical Analysis

Race-specific descriptive statistics were computed using sampling weight–adjusted means and standard errors of the mean for continuous measures and sampling weight-adjusted proportions for discrete measures. Two sample comparisons were made using generalized linear models, adjusting for sampling weights. We used a Cox proportional hazards regression model to examine the relative risk of overall and total mortality using two indicators for the APOE ε2 allele and the APOE ε4 allele after adjusting for demographic and health covariates. A race-specific Cox model was used to examine covariate confounding in AAs and EAs, and a combined model with a race interaction with the risk alleles was used to test whether these associations were significantly different between AAs and EAs. For the age-dependent analysis, a combined model was used to examine the trend in the association between the APOE alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality according to age (65–69, 70–79, ≥80). An interaction of the linear term for the three age groups and the risk alleles was used to examine the age-dependent trend in these associations. The proportional hazards assumptions of the Cox models for overall and cardiovascular mortality were met. We also examined the variance inflation factor of covariates in our regression model and found no evidence of multicollinearity. All analyses were performed using survival package in R program33 and a bootstrap variance over 1,000 bootstrap samples for estimating the appropriate standard errors.23,34

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The average age of study participants was 71.6 (standard error (SE) 0.13) at baseline (Table 1). The 4,917 participants had an average education of 12.7 years, 1,915 (39%) had died at an average age of 83.9, 3,348 (68%) were AA, and 3,095 (64%) were female. Cardiovascular mortality was approximately 18%, which was about half that of NDI-confirmed deaths.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Health Characteristics of 4,917 African Americans and European Americans

| Characteristic | Combined, N = 4,917 |

African American, n = 3,348 |

European American, n = 1,569 |

P- Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, mean (SE) | 71.6 (0.13) | 70.5 (0.13) | 73.7 (0.27) | <.001 |

| Age at death, mean (SE) | 83.9 (0.23) | 82.7 (0.30) | 85.9 (0.34) | <.001 |

| Education, years, mean (SE) | 12.7 (0.10) | 11.7 (0.12) | 14.3 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SE) | 28.5 (0.16) | 29.1 (0.21) | 27.3 (0.26) | <.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean (SE) | 138.0 (0.52) | 138.0 (0.67) | 138.0 (0.82) | .98 |

| Physical activity, h/wk, mean (SE) | 3.0 (0.13) | 2.5 (0.14) | 3.9 (0.26) | <.001 |

| Alcohol consumption, g/d, mean (SE) | 6.2 (0.47) | 4.5 (0.58) | 9.3 (0.77) | <.001 |

| Composite cognitive function, mean (SE) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.61 (0.02) | <.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 3,095, 64 | 2,144, 65 | 951,62 | .13 |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 1,930, 40 | 1,270,40 | 660, 41 | .69 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 639, 13 | 495, 14 | 144, 11 | .08 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1,915, 38.9 | 1,113,39.9 | 802, 49.1 | .001 |

| Cardiovascular mortality, n (%) | 699, 17.8 | 360, 15.0 | 339,21.9 | .001 |

P-values are based on generalized linear models and chi-square test statistics for survey design using sampling weights to compare African Americans and European Americans.

SE = standard error.

A large number of demographic and health characteristics were different between AAs and EAs (Table 1). In general, AAs had less education, higher BMI, and lower physical activity and consumed fewer alcoholic beverages. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was similar between AAs and EAs. In age-unadjusted descriptive analysis, overall and cardiovascular mortality were higher in EAs than AAs, because EAs were approximately 3 years older than AAs (P < .001).

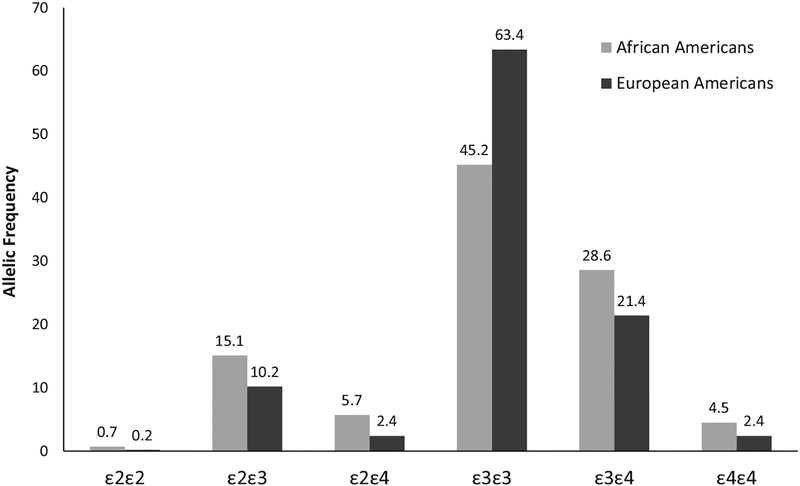

Frequency of APOE Alleles in AAs and EAs

The allelic frequency of the APOE genotypes in AAs and EAs is shown in Figure 1. The frequencies of all APOE genotypes were different between AAs and EAs (P < .001). A significantly higher proportion of AAs (22%) than of EAs (13%) had one or more APOE ε2 alleles (ε22/ε23/ε24) (P < .001). Similarly, a higher proportion of AAs had one or more APOE ε4 alleles (ε34/ε44) (33% vs 24%, P < .001). Also, the frequency of the APOE ε3ε3 allele, considered the “neutral” allele, was approximately 18 percentage points lower in AAs than EAs (45% vs 63%, P < .001). Our data suggest that AAs in general were more likely to have the APOE ε2 and ε4 alleles than EAs and less likely to have the ε3 homozygote.

Figure 1.

Allelic frequency of apolipoprotein E genotypes of 4,917 African Americans and European Americans.

Survival Curves of APOE Alleles and Overall Mortality

The survival curves for the four general categories of APOE genotypes (ε33, ε22 or ε23, ε24, ε34 or ε44) are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. The risk curves appear to be similar until age at death of 85. In contrast, separation in risk curves for later age at death can be seen in our data. Using a log-rank test, participants with the APOE ε22 or APOE ε23 allele had a lower risk of death than participants with the APOE ε33 genotype (p = .004), and participants with the APOE ε24 allele had risk similar to that of participants with the APOE ε22 or APOE ε24 allele (P = .10), so these two subgroups were combined into one. Participants with one or more APOE ε4 alleles had higher risk of death than those with the APOE ε33 risk allele (P = .001).

Relative Risk of Mortality and APOE Allele

Table 2 shows the association between the APOE ε2 and APOE ε4 alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality relative to the APOE ε33 genotype after adjusting for demographic and health covariates.

Table 2.

Risk of Death According to Apolipoprotein ε33 Genotype in 4,917 African Americans and European Americans

| Combined | African American | European American | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P-Value | ||

| Overall | ||||

| ε2 | 0.81 (0.76–0.87)a | 0.84 (0.77–0.92)a | 0.78 (0.69–0.88)a | .80 |

| ε4 | 1.10 (1.04–1.16)b | 1.11 (1.04–1.20)a | 1.09(1.03–1.17)c | .79 |

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| ε2 | 0.65 (0.58–0.76) | 0.62 (0.52–0.73) | 0.70 (0.60–0.82) | .72 |

| ε4 | 1.20 (1.07–1.29) | 1.21 (1.07–1.37)a | 1.20 (1.06–1.36)b | .99 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race (for combined model), education, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, alcohol consumption, cognitive function, and former and current smoking status.

P<.001,

.001,

.05.

The APOE ε2 allele was associated with 19% lower risk of overall mortality (HR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.76–0.87), which was not significantly different between AAs and EAs (P = .80). We also found that the APOE ε2 allele was associated with cardiovascular mortality, lowering the risk by 35% (HR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.58–0.76), which was not significantly different between AAs and EAs (P = .72). A greater association between the APOE ε2 allele and cardiovascular mortality suggests that some of the association observed with overall mortality may be through cardiovascular mortality.

The APOE ε4 allele was associated with 10% higher risk of mortality (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.04–1.16), and no racial differences were observed (P = .79). The association between the APOE ε4 allele and cardiovascular mortality was twice as high as with overall mortality; the relative risk of cardiovascular mortality was 20% greater in participants with the APOE ε4 allele (HR = 1.20, 95%CI = 1.07–1.29), suggesting that some of the association between the APOE ε4 allele and overall mortality may be through cardiovascular mortality.

The combined and race-stratified analyses suggest no effect modification of race on the association between APOE genotype and overall and cardiovascular mortality.

Relative Risk of Mortality and APOE Alleles by Age

The relative risk of mortality for the APOE alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality adjusted for demographic and health covariates is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk of Death According to Apolipoprotein E ε33 Genotype in 4,917 Participants According to Age

| ε2 | ε4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | n (%) | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Overall | |||

| 65–69 | 2,321 (47) | 0.87 (0.76–0.98)c | 0.99 (0.90–1.10) |

| 70–79 | 1,852 (38) | 0.82(0.71–0.91)b | 1.37 (1.26–1.49)a |

| ≥80 | 744 (15) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97)c | 0.83 (0.72–0.98)c |

| P-trend | .61 | .85 | |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| 65–69 | 2,321 (47) | 0.74 (0.57–0.96)c | 1.19 (1.02–1.38)c |

| 70–79 | 1,852 (38) | 0.86 (0.75–0.99)c | 1.39 (1.21–1.60)a |

| ≥80 | 744 (15) | 0.68 (0.52–0.86)c | 0.71 (0.57–0.89)b |

| P-trend | .76 | .003 | |

Models adjusted for age, sex, race (for combined model), education, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, alcohol consumption, cognitive function, and former and current smoking status.

P<.001,

.001,

.05.

The association between the APOE ε2 allele and overall mortality was largely age invariant. The relative risk was 13% to 18% lower and did not differ by age (P = .61). The APOE ε4 allele was not associated with overall mortality in people at younger ages (65–69), although the risk of overall mortality for people with the APOE ε4 allele was approximately 37% higher for those aged 70 to 79. At older ages, the association of the APOE ε4 allele and overall mortality was diminished.

The APOE ε2 allele was associated with lower risk of cardiovascular mortality in the three age groups. The association appeared to be largest in the oldest age group, but the trend for change in relative risk estimates was not significant (P = .76). The APOE ε4 allele was associated with a consistently higher risk of cardiovascular mortality in participants younger than 80, the association was substantially lower in those aged 80 and older, and a linear trend was also significant (P = .003).

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that the APOE ε2 allele is associated with lower risk of overall mortality and the APOE ε4 allele with higher risk of overall mortality than the ε33 allele. The associations were even stronger for cardiovascular mortality. Even though the allelic frequencies were substantially different between AAs and EAs, the associations between these alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality were similar in AAs and EAs. The age-dependent association between the APOE ε2 allele and overall mortality did not vary with age, but the risk of overall and cardiovascular mortality was highest in those with the APOE e4 allele aged 70 to 79.

The allelic frequency of the APOE genotypes has been a topic of great interest, because these alleles are associated with health conditions and mortality. Approximately 13% of EAs in our sample had the APOE ε2 allele, which is higher than reported in Europeans only,11 although the frequency of the APOE ε4 allele in EAs and were similar to those of Europeans.11 The frequency of the APOE ε4 allele was much higher in our sample than in Africans from Uganda.16 These differences in frequencies also translate into higher prevalence and absolute risk of chronic health conditions in AAs and EAs.

Several studies have shown that the APOE ε2 allele is not associated with overall mortality, but the sample sizes were relatively small7–9 with short follow-up9 or examined older age groups,8 making the associations inconsistent. In a large cohort study, the APOE ε2 allele was not associated with mortality in the oldest adults,15 but age differences would be the explanation for the differences because the APOE ε2 allele may behave differently with age. The size of our APOE ε2 allele sample was double that of the previous studies, and our study spanned more than 18 years. The relationship between the APOE ε4 allele and overall mortality has been inconsistent as well, with several studies with longer follow-up showing a positive association4,5 and those with shorter duration showing a null association.7–9 The association between APOE ε4 allele and mortality has been shown to increase with age.35 This finding is confirmed in our study, because the risk of mortality in those with the APOE ε4 allele increased with age. One of our strengths is the size of our study sample and the duration of the study. We collected DNA samples from 4,917 participants, with a large proportion of the sample being AAs. The follow-up period was longer than 18 years and provides better power to detect the association between the APOE risk alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality in AAs and EAs. One of the major limitations of our study is the assessment of cardiovascular mortality. Even though NDI classification uniform ascertains cause of death, there may be some underlying differences between AAs and EAs. The inclusion of Medicare assessments of cardiovascular events within 3 years before death or end of study did not change our findings. The APOE ε24 allele was combined with other APOE ε2 alleles, although in a sensitivity analysis, the association between the risk alleles and mortality did not change when he APOE ε24 allelic group was removed.

CHAP is based on a geographically defined urban community on the south side of Chicago. The allelic frequency in the four urban communities in Chicago may be different from that of the general U.S. population. Of the 10,802 participants in CHAP, 4,971 provided sufficient DNA samples for genotyping. Although DNA was collected in CHAP using a stratified random sample in an earlier study period, all participants were eligible for DNA extraction in the last two cycles of data collection, there may be selection bias due to individuals who were not chosen or part of the population sample. This selection bias may have resulted in a different allelic frequency than those part of the stratified random sample. In our study, more AAs provided DNA samples than EAs, which may also have led to selection bias in one or both racial groups. Participants who provided APOE genotypes were younger and, in general, had better cognitive functioning than those with no DNA samples and were more likely to be AA. Our regression approach adjusted for a large number of covariates that were significantly associated with overall and cardiovascular mortality. This makes the marginal association of APOE risk alleles with log hazard function. We carefully examined the proportional hazards assumption and variance inflation factors, which suggest that the assumptions of the regression approach were met in our analysis.

In summary, the association between the APOE ε2 and ε4 alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality seemed to persist even after accounting for demographic, cognitive, lifestyle, and chronic health measures. These associations were twice as large for cardiovascular mortality as for overall mortality. Gaining better mechanistic understanding of the relationship between the APOE alleles and overall and cardiovascular mortality might provide a better understanding of the underlying risk mechanism and make possible more-translational approaches to decrease mortality and increase lifespan in the general population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure: This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AG051635 (KBR) and R01 AG11101 (DAE).

Sponsor’s Role: The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design of the study, collection or analysis of the data, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soerensen M, Dato S, Tan Q et al. Evidence from case-control and longitudinal studies supports associations of genetic variation in APOE, CETP, and IL6 with human longevity. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:487–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schemchel D. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1993;43:1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA 1997;278:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosvall L, Rizzuto D, Wang HX et al. APOE-related mortality: Effect of dementia, cardiovascular disease and gender. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:1545–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Kaufman JS et al. Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele interacts with sex and cognitive status to influence all-cause and cause-specific mortality in U.S. older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichner JE, Dunn ST, Perveen G et al. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and cardiovascular disease: A HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafson DR, Mazzuco S, Ongaro F et al. Body mass index, cognition, disability, APOE genotype, and mortality: The “Treviso Longeva” Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heijmans BT, Slagboom PE, Gussekloo J et al. Association of APOE epsilon2/epsilon3/epsilon4 and promoter gene variants with dementia but not cardiovascular mortality in old age. Am J Med Genet 2002;107:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juva K, Verkkoniemi A, Viramo P et al. APOE epsilon4 does not predict mortality, cognitive decline, or dementia in the oldest old. Neurology 2000;54:412–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasher VP, Sajith SG, Rees SD et al. Significant effect of APOE epsilon 4 genotype on the risk of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease and mortality in persons with Down syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23:1134–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewbank DC. Mortality differences by APOE genotype estimated from demographic synthesis. Genet Epidemiol 2002;22:146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Risch NJ et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 1994;7:180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin R, Leake A, McArthur FK et al. Protective effect of APOE ε2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 1994;344:473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson PW, Myers RH, Larson MG et al. Apolipoprotein E alleles, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease. The Framingham Offspring Study. JAMA 1994;272:1666–1671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Tan Q, Mengel-From J et al. Effects of the APOE ε2 allele on mortality and cognitive function in the oldest old. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68A:389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbo RM, Scacchi R. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele distribution in the world. Is APOE*4 a ‘thrifty’ allele? Ann Hum Genet 1999;63:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nygaard M, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Soerensen M, et al. Birth cohort differences in the prevalence of longevity-associated variants in APOE and FOXO3A in Danish long-lived individuals. Exp Gerontol 2014;57:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Lantigua R et al. Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dilworth-Anderson P, Hendrie HC, Manly JJ et al. Diagnosis and assessment of Alzheimer’s disease in diverse populations. Alzheimers Dement 2008;4:305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkins LO. Epidemiology and burden of cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol 2004;27:III2–III6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skoog I, Hesse C, Aevarsson O et al. A population study of ApoE genotype at the age of 85: Relation to dementia, cerebrovascular disease, and mortality. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community. Arch Neurol 2003;60:185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Skarupski KA et al. Gene-behavior interaction of depressive symptoms and the apolipoprotein E4 allele on cognitive decline. Psychosom Med 2014;76:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajan KB, Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS et al. Association of cognitive functioning, incident stroke, and mortality in older adults. Stroke 2014;45:2563–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hixson J, Vernier DO. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with Hha l. J Lipid Res 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenham PR, Price WH, Blundell G. Apolipoprotein E genotyping by one-stage PCR. Lancet 1991;337:1158–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA et al. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neurosci 1991;57:167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Bienias JL et al. Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older adults. Neurology 2002;59:1910–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith A Symbol Digits Modalities Test. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh TR. ‘Mini-Mental State’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Beckett LA et al. Cognitive activity in older persons from a geographically defined population. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999;54B:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Barnes LL et al. Cognitive impairment 18 years prior to clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology 2015;85:898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, No. 57. London: Chapman and Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobsen R, Martinussen T, Christiansen L et al. Increased effect of the ApoE gene on survival at advanced age in healthy and long-lived Danes: Two nationwide cohort studies. Aging Cell 2010;9:1004–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.