Abstract

BACKGROUND

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation has been the standard treatment for young patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. However, promising emerging data with the combination of lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (RVD) have raised questions about the role of transplantation.

METHODS

We randomly assigned 700 patients to the RVD group (eight cycles; 350 patients) or to the transplant group (three cycles of RVD, followed by high-dose melphalan plus stem cell transplantation, followed by two additional cycles of RVD; 350 patients). Patients in both arms received maintenance lenalidomide for 1 year. The primary end point was progression-free survival.

RESULTS

Progression-free survival was significantly longer in the transplant versus the RVD group (median, 50 months vs. 36 months; hazard ratio, 0.65; P<0.001). This benefit was observed across all patient subgroups, including those stratified by International Staging System stage and cytogenetic risk profile. Transplantation versus RVD alone was associated with increased complete response (59% vs. 48%; P=0.006), and minimal residual disease negativity (79% vs. 65%; P<0.001). Overall survival was similar in both arms (4-year survival, 81% in the transplant group vs. 82% in the RVD group). Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia was significantly more common with transplantation than with RVD (92% vs. 47%), as were gastrointestinal adverse events (28% vs. 7%) and infections (20% vs. 9%). Rates of treatment-related deaths, second primary malignancies, thromboembolic events, and peripheral neuropathy were similar in the two treatment groups.

CONCLUSIONS

RVD plus transplant significantly prolonged progression-free survival as compared with RVD alone without overall survival difference.

For the past 20 years, high-dose chemotherapy plus autologous stem cell transplantation has been the standard treatment for newly diagnosed myeloma in patients younger than 65 years of age1,2. However, this procedure requires hospitalization and can be associated with substantial toxicity.

Over the past decade, immunomodulatory drugs3–13 and proteasome inhibitors14–16 have demonstrated significant activity in myeloma patients. Immunomodulatory drugs combined with proteasome inhibitors and dexamethasone have resulted in unprecedented complete response rates and improved outcomes in both transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible patients.17–20 The benefits observed with these combinations have led investigators to propose their use in newly diagnosed patients, and have raised questions about the role and timing of transplantation in the initial management of younger patients.

To address this issue, we conducted a phase 3 study to compare the efficacy and safety of the combination of lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) alone versus RVD plus transplantation, in younger patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.

METHODS

CRITERIA FOR ENROLLMENT

Eligible patients were 65 years of age or less and presented with symptomatic, measurable, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Additional eligibility criteria included: serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels no more than two times the upper limit of the normal range; serum bilirubin level no more than 35 μmol per liter (2 mg/dl); creatinine clearance of at least 50 ml per minute; absolute neutrophil count of at least 1000 per cubic millimeter; platelet count of more than 50,000 per cubic millimeter; and normal cardiac and pulmonary function. Main exclusion criteria included a history of other cancer, and peripheral neuropathy of grade 2 or higher. Women of child-bearing potential were eligible if they agreed to use contraception, produced a negative pregnancy test prior to enrollment, and agreed to undergo monthly pregnancy testing until 4 weeks after the discontinuation of study medication. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the coordinating center (Purpan Hospital, Toulouse, France). All patients provided written informed consent.

STUDY DESIGN AND TREATMENT

The study was a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial conducted at 69 centers in France, Belgium, and Switzerland. Patients were recruited from November 2010 through November 2012 and were randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to one of the two treatment groups during the first cycle of induction therapy. Randomization was stratified by International Staging System disease stage (stage I, II, or III) and cytogenetic risk profile (standard or high risk, or test failure; high risk defined as t(4:14) translocation or t(14:16) translocation, or 17p deletion, as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization).

All patients received induction therapy consisting of three 21-day cycles of lenalidomide (25 mg, orally, on days 1 through 14), bortezomib (1.3 mg per square meter, intravenously, on days 1, 4, 8, and 11), and dexamethasone (20 mg, orally, on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12) [the so-called RVD regimen]. Following induction, all patients underwent stem cell mobilization with cyclophosphamide and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. The consolidation regimen comprised either five cycles of RVD with a reduced daily dexamethasone dose of 10 mg (RVD group), or melphalan at a dose of 200 mg per square meter with autologous stem cell transplantation followed by two cycles of RVD with a reduced daily dexamethasone dose of 10 mg (transplant group). In both treatment arms, lenalidomide maintenance therapy (10 mg per day for the first 3 months, increased to 15 mg if tolerated) was initiated within the first 3 weeks after completion of consolidation therapy, and was continued for 1 year or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of patient consent. For patients in the RVD group, salvage transplantation was recommended at the time of disease progression. Permitted concomitant therapies are described in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

The primary end point was progression-free survival. Secondary end points included response rate, time to disease progression, overall survival, and safety. Toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria of Adverse Events (version 4.0). Serious adverse events and interim efficacy analyses were reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring committee.

The senior academic authors designed the trial and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. The sponsor (Toulouse Hospital) collected the data and performed the analyses in collaboration with the senior academic authors and an independent data and safety monitoring committee. All authors had full access to the primary data and results of the final analysis, took the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses. Celgene and Janssen provided lenalidomide and bortezomib, respectively. The French Institute for Cancer, Celgene, and Janssen funded the trial, but played no other role. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, which, along with the statistical analysis plan, is available at NEJM.org.

ASSESSMENTS

Response to treatment and disease progression were assessed according to the International Uniform Response Criteria.21 Complete disappearance of M-protein in serum and urine on immunofixation was considered to be a complete response if confirmed by bone marrow evaluation, and a very good partial response in the absence of bone marrow evaluation. Bone marrow samples were collected from all patients at enrollment for cytogenetic evaluation, and also after consolidation and maintenance from patients who achieved a complete or very good partial response, for minimal residual disease (MRD) measurement by 7-color flow cytometry (sensitivity level 10−4)19. Blood and urine samples were collected every 4 weeks from randomization until disease progression. Patients with progressive disease were followed up every 3 months to determine survival status.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The sample size was determined assuming a median progression-free survival of 30 months in the RVD arm and 39 months in the transplant arm. The study had at least 80% statistical power to detect a difference in two survivorship functions using a two-sided log-rank test with overall significance level of 0.05 (adjusted for two interim analyses at 33% and 69% of events). Critical values at interim analysis were determined using Lan-DeMets error spending rate functions corresponding to O’Brien-Fleming stopping boundaries.

The second interim analysis was performed in June 2015. The results were submitted to the independent data monitoring committee, who recommended their release because the difference in progression-free survival met the pre-specified stopping criterion (p<0.015). Progression-free survival was defined as the time from randomization until either the first documentation of progressive disease or death due to any cause. Censoring rules for progression-free survival followed the FDA guidance on endpoints in cancer trials. Time to progression was defined as the time from randomization until either progressive disease or death due to myeloma. Overall survival was defined as the time from randomization until death. Follow-up was estimated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method.22 Time-to-event end points were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier method, using a stratified log-rank test to compare the treatment arms and a Cox proportional hazards model to estimate hazard ratios along with 95% confidence intervals. Analyses of progression-free survival in specific subgroups were pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan and performed using Cox models with terms for treatment arm, subgroup, and the interaction between subgroup and treatment. The interaction terms were evaluated for statistical significance. Response rates were compared between groups using a Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Second primary malignancy incidence rates were calculated as the ratio of the number of second primary malignancies and the number of patient-years at risk, and were compared using a binomial exact test. Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, with a data cutoff of September 1, 2015 (Steering Committee date), and were predefined in the statistical analysis plan and conducted using Stata® Version 14.0.

RESULTS

PATIENTS AND TREATMENTS

A total of 764 patients were enrolled, 57 of whom did not meet the eligibility criteria. Seven patients entered the first cycle of RVD but were not randomized (patient or investigator decision, n = 5; severe adverse event, n = 2). Seven hundred patients were randomized, 350 to the RVD group and 350 to the transplant group. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Randomized Patients.

| Characteristic | RVD Group (N = 350) |

Transplant Group (N = 350) |

|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | ||

| Median | 59 | 60 |

| Range | 29−66 | 30−66 |

| Male sex — n (%) | 208 (59) | 214 (61) |

| Type of myeloma — n (%) | ||

| IgG | 209 (60) | 223 (64) |

| IgA | 71 (20) | 73 (21) |

| Light chain | 57 (16) | 46 (13) |

| Others | 13 (4) | 8 (2) |

| International Staging System stage — n (%) | ||

| I | 115 (33) | 118 (34) |

| II | 170 (49) | 171 (49) |

| III | 65 (19) | 61 (17) |

| Serum beta-2 microglobulin level — n (%) | ||

| <3.5 mg/liter | 169 (48) | 178 (51) |

| 3.5−5.5 mg/liter | 116 (33) | 111 (32) |

| >5.5 mg/liter | 65 (19) | 61 (17) |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities†, n/evaluable¶ | ||

| t(4;14) translocation | 26/256 | 28/259 |

| Deletion of chromosome 17 | 15/256 | 16/258 |

| t(14;16) translocation | 6/256 | 6/258 |

| t(4;14) or t(14;16)translocation or deletion of chromosome 17 | 44/256 | 46/259 |

Data from fluorescence in situ hybridization. Patients could have more than one abnormality.

For technical reasons, 94 patients in the RVD group and 91patients in the transplant group were not evaluable.

In the RVD group, 331 (95%) patients entered the consolidation phase and 321 (92%) entered the maintenance phase. In the transplant group, 323 (92%) patients underwent transplantation, 315 (90%) entered the RVD phase post-transplantation, and 311 (89%) entered the maintenance phase.

RESPONSE RATES

Depth of response was improved with transplantation versus RVD (P=0.004) (Table 2). The complete response rate was 48% in the RVD group versus 59% in the transplant group (P=0.006). Complete or very good partial response rates in the RVD versus transplant group were 45% versus 47% after induction (P=0.47), 70% after transplantation, 69% versus 78% after consolidation (P=0.01), and 76% versus 85% after maintenance (P<0.002). MRD was not detectable in 65% of patients in the RVD group versus 79% of patients in the transplant group (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Response to Treatment.

| RVD Group (N = 350) |

Transplant Group (N = 350) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Response During Study* | 0.004 | ||

| Complete response — n (%) | 169 (48) | 205 (59) | |

| VGPR — n (%) § | 101 (29) | 102 (29) | |

| Partial response — n (%) | 70 (20) | 37 (11) | |

| Stable disease — n (%) | 10(3) | 6 (2) | |

| Complete response — n (%) | 169 (48) | 205 (59) | 0.006 |

| Complete response or VGPR — n (%) | 270 (77) | 307 (88) | <0.001 |

| MRD negative during study — n (%) ¶ | 171/265 (65) | 220/278 (79) | <0.001 |

Responses were assessed according to the International Uniform Response Criteria for Multiple Myeloma.

VGPR denotes very good partial response.

MRD denotes minimal residual disease and was measured by flow cytometry, in bone marrow samples taken from patients achieving a complete or a very good partial response.

PROGRESSION-FREE SURVIVAL, TIME TO PROGRESSION, AND OVERALL SURVIVAL

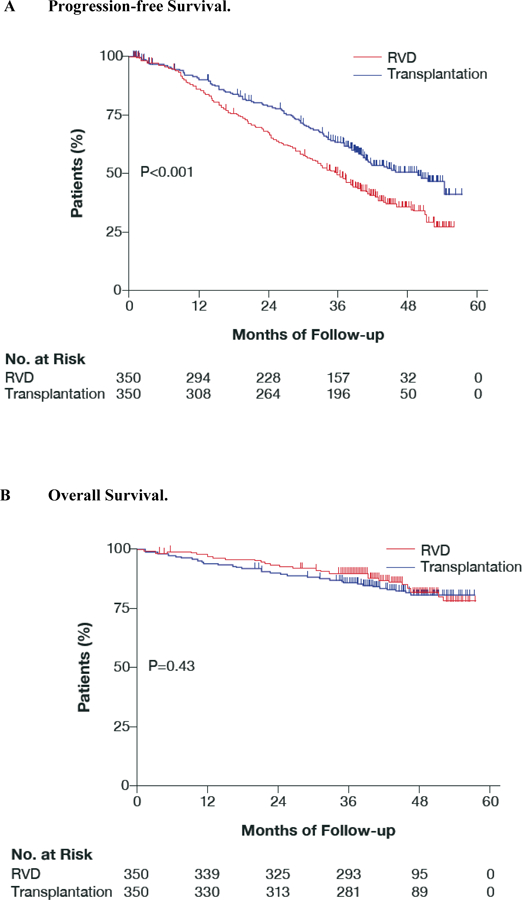

The median duration of follow-up from randomization was 43 months. Disease progression or death occurred in 368 patients (211 in the RVD group and 157 in the transplant group). Median progression-free survival was 36 months in the RVD group versus 50 months in the transplant group (hazard ratio, 0.65; P<0.001). Four-year progression-free survival was 35% in the RVD group versus 50% in the transplant group (Fig. 1A). Age, sex, isotype of the monoclonal component, International Staging System disease stage, and cytogenetic profile did not significantly modify the progression-free survival benefit associated with transplantation (Fig. 2). Progression-free survival was prolonged in MRD-negative versus MRD-positive patients (hazard ratio, 0.33; P<0.001) (Fig. S1A in the supplementary appendix). This benefit was similar in the two treatment groups (P=0.941 for interaction).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Progression-free Survival and Overall Survival according to Treatment Group.

Panel A shows progression-free survival. Median progression-free survival was 36 months in the RVD group and 50 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.65; P <0.001)

Panel B shows overall survival. The overall survival 4 years after randomization was similar in both arms (hazard ratio, 1.14; P=0.43).

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Progression-free Survival, showing Hazard Ratios by Patient Subgroups.

The figure shows that the progression-free survival benefit associated with transplantation was consistent across all subgroups of patients defined by age, sex, type of myeloma, International Staging System stage, or cytogenetic features.

The position of each square represents the point estimate of the treatment effect; horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Median time to progression with RVD versus transplantation was 36 months versus 50 months (hazard ratio, 0.62; P<0.001).

Overall survival at 4 years was similar in the two study groups (82% in the RVD group, 81% in the transplant group; P=0.43) (Fig. 1B). Median survival was not reached in either group. Overall survival was prolonged in MRD-negative versus MRD-positive patients (hazard ratio, 0.37; P<0.001) (Fig. S1B in the supplementary appendix).

SALVAGE THERAPY

In the RVD group, disease progression was reported in 207 patients, and 172 symptomatic patients received a second-line therapy: pomalidomide-based (61 patients), lenalidomide-based (3 patients), bortezomib-based (72 patients), alternative novel agent-based (5 patients), or chemotherapy without a novel agent (31 patients). Second-line therapy was followed with salvage transplantation in 136/172 patients (79%). For the remaining 36 patients, transplantation was not performed mostly due to disease refractoriness.

In the transplant group, 149 patients experienced disease progression, and 123 symptomatic patients received a second-line therapy: pomalidomide-based (53 patients); lenalidomide-based (4 patients); bortezomib-based (47 patients); alternative novel agent-based (4 patients); or chemotherapy without a novel agent (15 patients). Twenty-one of the 123 patients treated for progression (17%) received a second transplant at the time of progression.

ADVERSE EVENTS

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events are listed in Table 3. In the RVD group, 32 patients (9%) discontinued treatment because of adverse events. In the transplant group, 39 patients (11%) discontinued treatment because of adverse events, and four transplant-related deaths occurred. Grade 3 or 4 adverse events that occurred more frequently in the transplant group versus the RVD group were: hematologic toxicity (95% vs. 64%, P<0.001), gastrointestinal disorders (28% vs. 7%, P<0.001), and infections (20% vs. 9%, P<0.001).

Table 3.

Grade 3 and 4 Adverse Events Occurring in at least 2% of Patients.

| RVD group (N = 350) |

Transplant group (N = 350) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Patients — n (%) | ||

| Any event | 292 (83.4) | 340 (97.1) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 223 (63.7) | 332 (94.9) |

| Neutropenia | 166 (47.4) | 322 (92.0) |

| Febrile neutopenia | 12 (3.4) | 52 (14.9) |

| Anemia | 31 (8.9) | 69 (19.7) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 50 (14.3) | 291 (83.1) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 24 (6.9) | 97 (27.7) |

| Nausea and Vomiting | 5 (1.4) | 25 (7.1) |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 59 (16.9) |

| Diarrhea | 10 (2.9) | 15 (4.3) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 14 (4.0) | 16 (4.6) |

| Cytolytic hepatitis | 11 (3.1) | 7 (2.0) |

| General disorders | 22 (6.3) | 30 (8.6) |

| Fatigue | 7 (2.0) | 6 (1.7) |

| Pyrexia | 1 (0.3) | 13 (3.7) |

| General physical health deterioration | 7 (2.0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Infections | 31 (8.9) | 71 (20.3) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 14 (4.0) | 23 (6.6) |

| Sepsis | 6 (1.7) | 18 (5.1) |

| Nervous system disorders | 48 (13.7) | 59 (16.9) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 42 (12.0) | 45 (12.9) |

| Grade 2 painful neuropathy | 3 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Skin | 18 (5.1) | 11 (3.1) |

| Rash | 7 (2.0) | 4 (1.1) |

| Vascular disorders | 11 (3.1) | 14 (4.0) |

| Deep-vein thrombosis | 5 (1.4) | 10 (2.9) |

| All thromboembolic events§ | 13 (3.7) | 19 (5.4) |

Including: deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, ischemic cardiopathy, and ischemic stroke.

SECOND PRIMARY MALIGNANCIES

The incidence of second primary malignancies did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The incidence rate for invasive second primary malignancies was 1.1 per 100 patient-years in the RVD group versus 1.5 per 100 patient-years in the transplant group (P=0.37). Three cases of acute myeloid leukemia occurred in the transplant arm.

DISCUSSION

Before the novel agent era, several randomized trials have demonstrated that transplantation was superior to conventional chemotherapy.1,2 Our trial is the first to compare transplantation with a combination of new drugs including both lenalidomide and bortezomib. Our study indicates that consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy plus transplantation significantly improves progression-free survival (the primary end point) versus RVD alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. Transplantation was also associated with a significantly increased complete response, MRD negativity, and median time to progression.

Overall survival was impressively high in both treatment groups: these positive results may be related to the use of RVD in both treatment arms, as well as the high level of activity of novel agents used to treat relapse.23 The similarity in overall survival between the two groups may also be related to the successful use of rescue transplantation. Several randomized trials comparing early transplant versus conventional dose treatment, in which rescue transplant was allowed, reported a progression-free survival benefit in favor of early transplant, without a difference in overall survival.24 Two recent studies, where transplantation was compared with an alkylating-based regimen plus lenalidomide followed by rescue transplantion, reported overall survival benefit with frontline transplantation.25,26 However, these regimens did not include proteasome inhibitors, have not been shown to improve overall survival compared with melphalan-prednisone27, and similarly compared poorly to transplant. Our trial thus demonstrates that in the era of new drugs delayed transplant is both valuable and feasible with no decrement in terms of overall survival benefit. Encouragingly, our study demonstrates that transplantation significantly increases MRD negativity versus RVD alone (P<0.001), with significantly prolonged overall survival in MRD-negative versus MRD-positive patients (P<0.001) overall, regardless of which arm patients were assigned to. These findings confirm MRD negativity as an important goal in myeloma28,29 , and support frontline transplantation as an effective strategy as well as RVD alone. MRD was assessed in our trial by 7-color flow cytometry (sensitivity 10–4)19 but not by the more sensitive next generation flow technology, which may in turn reveal more subtle differences in outcome.30

Maintenance treatment with lenalidomide after transplantation significantly improves survival for patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.31,32 However, the optimal duration of maintenance is still a matter of debate. In our study, maintenance was administered for 1 year in order to limit toxicities. The ongoing, collaborative, parallel US trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01208662, the Determination study) is using a similar design, but with maintenance lenalidomide administered continuously until progression. Comparison of these two parallel trials will shed further light on this important question.

Hematologic and non-hematologic adverse events were more common with transplantation than with RVD; however, toxic effects were consistent with established toxicity profiles of transplantation. Acute myeloblastic leukemia is part of the natural history of myeloma and its treatment, particularly in the context of melphalan use.33 However, the few observed cases in the transplant arm will require longer follow-up to properly quantify risk.

In conclusion, we found that consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy plus transplantation versus RVD improves progression-free survival without overall survival difference. This benefit must be weighed against the increased risk of toxicity. Outcomes in both arms of our study are among the best reported to date in this setting, including a high rate of MRD negativity. These encouraging results suggest that new drug combinations using newer proteasome inhibitors, next generation IMID’s, potent monoclonal antibodies, and transplantation tailored according to MRD could further improve the outcome of younger myeloma patients.34–38

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the members of the data and safety monitoring committee: Joan Blade M.D., Ralph d’Agostino Ph.D., Robert Kyle M.D., Joseph Massaro M.D., Jean Pearlstein J.D., and Christian Straka M.D.; representatives of the sponsor who were involved in data collection and analyses: Catherine Gentil, Laure Devlamynck, Pascale Olivier, Marie Elise Llau, and Marie Odile Petillon. The lenalidomide and bortezomib utilized in this trial were provided by Celgene and Janssen Corporation. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Sandralee Lewis of the investigator Initiated Research Writing Group (an initiative from Ashfield Healthcare Communications, part of UDG Healthcare plc), and was funded by Celgene.

ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT01191060

Supported by the French “Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique”, by the French National Research Agency (ANR-11-PHUC-001-CAPTOR project), and by a grant from Celgene and Janssen.

Footnotes

*A complete list of IFM 2009 Study investigators is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org

Contributor Information

Michel Attal, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, Toulouse

Valerie Lauwers-Cances, Service d’Epidémiologie, Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire de Toulouse

Cyrille Hulin, Hôpital Haut-Lévêque, Bordeaux Pessac

Xavier Leleu, Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire la Miletrie, Poitiers

Denis Caillot, Centre Hospitalier Le Bocage, Dijon

Martine Escoffre, Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire de Rennes

Bertrand Arnulf, Hôpital St-Louis, Paris

Margaret Macro, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, Toulouse

Karim Belhadj, Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire Henri Mondor, Creteil

Laurent Garderet, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Hôpital St-Antoine, Paris

Murielle Roussel, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, Toulouse

Catherine Payen, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, Toulouse

Claire Mathiot, Institut Curie, Paris

Jean Paul Fermand, Hôpital St-Louis, Paris

Nathalie Meuleman, Institut Jules Bordet, Brussels

Sandrine Rollet, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, Toulouse.

Michelle E. Maglio, Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire de Rennes

Andrea A. Zeytoonjian, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Edie A. Weller, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Nikhil Munshi, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Kenneth C. Anderson, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

Paul G. Richardson, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston

Thierry Facon, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille

Hervé Avet-Loiseau, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse-Oncopole, Toulouse

Jean-Luc Harousseau, Haute Autorité de Santé, Paris

Philippe Moreau, Hôtel Dieu, Nantes

REFERENCES

- 1.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 1996;335:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl Med 2003;348:1875–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facon T, Mary JY, Hulin C, et al. Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide versus melphalan and prednisone alone or reduced-intensity autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients with multiple myeloma (IFM 99–06): a randomised trial. Lancet 2007;370:1209–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hulin C, Facon T, Rodon P, et al. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: IFM 01/01 trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3664–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Caravita T, et al. Italian Multiple Myeloma Network, GIMEMA. Oral melphalan and prednisone chemotherapy plus thalidomide compared with melphalan and prednisone alone in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006; 367:825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waage A, Gimsing P, Fayers P, et al. Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide or placebo in elderly patients with multiple myeloma. Blood 2010;116:1405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wijermans P, Schaafsma M, Termorshuizen F, et al. Phase III study of the value of thalidomide added to melphalan plus prednisone in elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the HOVON 49 study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beksac M, Haznedar F, Firatli-Tuglular T, et al. Addition of thalidomide to oral melphalan/prednisone in patients with multiple myeloma not eligible for transplantation: results of a randomized trial from the Turkish Myeloma Study Group. Eur J Haematol 2011;86:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimopoulos MA, Chen C, Spencer A, et al. Long-term follow-up on overall survival from the MM-009 and MM-010 phase III trials of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2009;23:2147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant- ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:906–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:906–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harousseau J-L, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005–01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4621–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IG, van der Holt, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/ GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2946–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Rossi D, et al. Bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide followed by maintenance with bortezomib-thalidomide compared with bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:5101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone compared with thalidomide and dexamethasone as induction before and consolidation therapy after double autologous stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results from a randomized phase III study. The Lancet 2010; 376:2075–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roussel M, Lauwers-Cances V, Robillard N, et al. Front-line transplantation program with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination as induction and consolidation followed by lenalidomide maintenance in patients with multiple myeloma: a phase II study by the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32:2712–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2010;116:679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2006;20:1467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies on failure time. Control Clin Trials 1996;17:343–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laubach JP, Voorhees PM, Hassoun H, Jakubowiak A, Lonial S, Richardson PG. Current strategies for treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Expert Rev Hematol 2014;7(1):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau P, Avet-Loiseau H, Harousseau JL, Attal M. Current trends in autologous stem-cell transplantation for myeloma in the era of novel therapies. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Di Raimondo F, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:1617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palumbo A, Hajek R, Delforge M, et al. Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paiva B, Vidriales MB, Cerveró J, et al. ; GEM (Grupo Español de MM)/PETHEMA (Programa para el Estudio de la Terapéutica en Hemopatías Malignas) Cooperative Study Groups. Multiparameter flow cytometric remission is the most relevant prognostic factor for multiple myeloma patients who undergo autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood 2008;112:4017–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rawstron AC, Child JA, de Tute RM, et al. Minimal residual disease assessed by multiparameter flow cytometry in multiple myeloma: impact on outcome in the Medical Research Council Myeloma IX Study. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:2540–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawstrom AC, Paiva B, Stetler-Stenson M. Assessment of minimal residual disease in myeloma and the need for a consensus approach. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2016; 90:21–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1782–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarthy P, Owzar K, Hofmeister C, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1770–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong C, Hemminki K. Second primary neoplasms among 53 159 heamatolymphoproliferative malignancy patients in Sweden, 1958–1996: a search for common mechanisms. Br J Cancer 2001; 85: 997–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:142–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. Oral Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1621–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD38 with Daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lonial S, Weiss BM, Usmani SZ et al. Daratumumab monotherapy in patients with treatment-refractory multiple myeloma (SIRIUS): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1551–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. Elotuzumab Therapy for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:621–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.