Abstract

Identification of Mendelian genes for neurodevelopmental disorders using exome sequencing to study autosomal recessive (AR) consanguineous pedigrees has been highly successful. To identify causal variants for syndromic and non-syndromic intellectual disability (ID), exome sequencing was performed using DNA samples from 22 consanguineous Pakistani families with ARID, of which 21 have additional phenotypes including microcephaly. To aid in variant identification, homozygosity mapping and linkage analysis were performed. DNA samples from affected family member(s) from every pedigree underwent exome sequencing. Identified rare damaging exome variants were tested for co-segregation with ID using Sanger sequencing. For seven ARID families, variants were identified in genes not previously associated with ID, including: EI24, FXR1 and TET3 for which knockout mouse models have brain defects; and CACNG7 and TRAPPC10 where cell studies suggest roles in important neural pathways. For two families, the novel ARID genes CARNMT1 and GARNL3 lie within previously reported ID microdeletion regions. We also observed homozygous variants in two ID candidate genes, GRAMD1B and TBRG1, for which each has been previously reported in a single family. An additional 14 families have homozygous variants in established ID genes, of which 11 variants are novel. All ARID genes have increased expression in specific structures of the developing and adult human brain and 91% of the genes are differentially expressed in utero or during early childhood. The identification of novel ARID candidate genes and variants adds to the knowledge base that is required to further understand human brain function and development.

Introduction

Over the past decade next-generation sequencing (NGS) has been used to elucidate the genetic etiology of Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders (Ng et al. 2009, 2010; O’Roak et al. 2011). Exome sequencing has been particularly beneficial in the identification of variants involved in the etiology of intellectual disability (ID), a trait characterized by both extensive phenotypic variability and genetic heterogeneity. A review of ID genes that have strong evidence of causality initially produced a list of 650 genes, of which ~ 62% of the variants had autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance, ~ 16% X-linked inheritance, ~ 3% autosomal dominant inheritance and 19% de novo (Kochinke et al. 2016); this list of known and candidate human ID genes has grown to 1948 in the SysID database. Around 25% of these genes are also associated with microcephaly (Kochinke et al. 2016), for which inheritance is primarily AR (Rump et al. 2016). It is estimated that there could be thousands of genes involved in ID etiology (van Bokhoven 2011).

In exome sequencing studies of heterogeneous groups of ID patients, the percentage of identified causal variants ranges from 16 to 68% (de Ligt et al. 2012; Srivastava et al. 2014; Rump et al. 2016; Tarailo-Graovac et al. 2016; Thevenon et al. 2016), suggesting that for a significant proportion of ID patients the genetic etiology remains unknown. The low yield may be due to technological limits of variant detection, lack of availability of additional family members, large numbers of variants that are identified for probands, or the causal variant lies outside of the coding regions.

In contrast, there has been a high yield for ARID gene discovery by exome sequencing of DNA samples from consanguineous families with various ID-associated pheno-types. In several published cohorts consisting of predominantly consanguineous ARID families from the Middle East and Pakistan (number of families ranging from 18 to 337), detection rates of putatively causal variants from NGS studies range from 37 to 90% and an aggregate of 327 novel or candidate ARID genes were identified (Najmabadi et al. 2011; Yavarna et al. 2015; Charng et al. 2016; Megahed et al. 2016; Riazuddin et al. 2017; Anazi et al. 2017; Reuter et al. 2017; Harripaul et al. 2017; Monies et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2018).

Here, we report on newly identified ARID genes, observation of variants in candidate ID genes which have only been previously reported in a single family in the literature, and novel variants in previously published ID genes. These discoveries were made through the study of exome sequence data from consanguineous Pakistani families segregating syndromic and nonsyndromic ARID. As was observed in previous studies, unique variants and genes were identified in most of these families. For the 22 families, we also observed three families segregating two homozygous ARID variants: two families with multi-genic inheritance where one of the two genes is likely to be sufficient to cause ARID etiology, and one family with locus heterogeneity (Fig. 1; Table 1). The involvement of these novel genes and variants in ARID etiology are supported by genome-wide linkage studies, expression in the developing and adult human brain, and published literature on knockout animal models, cell studies and microdeletions involved in ID etiology.

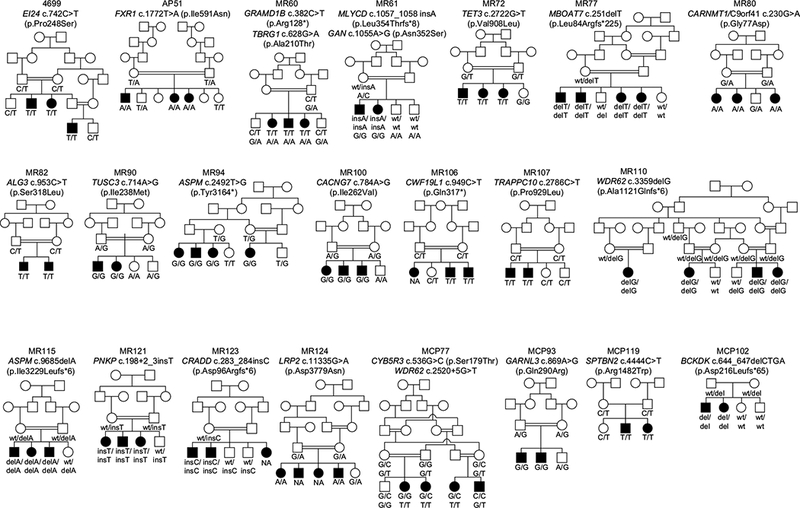

Fig. 1.

Pedigree drawings and genotypes of 22 consanguineous Pakistani families with intellectual disability (ID) 19 families have a single variant co-segregating with ID. For two families MR60 and MR61 two variants both co-segregate with ID in the entire family. For family MCP77 there is intra-familial genetic heterogeneity, such that three affected individuals are homozygous for a WDR62 variant while one individual with ID is homozygous for a CYB5R3 variant

Table 1.

Phenotypic description and genes identified in 22 pakistani families with syndromic and non-syndromic autosomal recessive intellectual disability (ARID)

| Family | Individual | Age (years) | Sex | Head circ. (cm) | IQ | Severity of ID | Other features | Gene | Known phenotype for gene | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4699 | 4699–4 | 20 | M | 58.4 | 55–60 | Mild | Lower limb spasticity, hearing

impairment, poor speech, unable to walk or stand; mild generalized

ichthyosis due to STM varianta; 4699–5 also

has palpebral ptosis |

EI24 | Novel ARID gene | |

| 4699–5 | 18 | F | 56.2 | 55–60 | Mild | |||||

| 4699–6 | 14 | M | 58.2 | 45–50 | Moderate | |||||

| AP51 | AP51–1 | 16 | M | 53 | 30 | Severe | Alopecia | FXR1 | Novel ARID gene | |

| AP51–3 | 18 | F | 53 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| AP51–4 | 20 | F | 54 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MR60 | MR60–1 | 12 | M | 50 | 30 | Severe | None | GRAMD1B and TBRG1 | GRAMD1B: moderate ARID | |

| MR60–3 | 20 | F | 52 | 25 | Severe | Delayed ambulation, poor speech | TBRG1: severe ARID with severe developmental (motor and speech) delay | |||

| MR60–4 | 10 | F | 49 | 30 | Severe | None | ||||

| MR61 | MR61–1 | 20 | F | 51 | 45 | Moderate | None | GAN and MLYCD | GAN: AR chronic polyneuropathy, kinky hair, leg posture, which can also include psychomotor delay and intellectual disability MLYCD: AR malonyl-CoA decarboxy lase deficiency: variable e.g. developmental delay/ID, metabolic acidosis, cardiomyopathy, hypoglycemia, seizures | |

| MR61–2 | 22 | M | 54 | 50 | Moderate | Aggressive behavior | ||||

| MR72 | MR72–1 | 14 | M | 53 | 45 | Moderate | Delayed ambulation, poor speech | TET3 | Novel ARID gene | |

| MR72–2 | 17 | F | 53 | 40 | Moderate | |||||

| MR72–3 | 20 | F | 51.5 | 40 | Moderate | |||||

| MR77 | MR77–4 | 32 | M | 55 | 30 | Severe | Speech disability | MBOAT7 | ARID with epilepsy and autism | |

| MR77–5 | 29 | M | 53.8 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MR77–6 | 28 | F | 52.5 | 25 | Severe | |||||

| MR77–7 | 19 | F | 51.2 | 25 | Severe | |||||

| MR80 | MR80–4 | 28 | F | 53 | 40 | Moderate | Hypotonia, hypertelorism, facial | CARNMT1 | Novel ARID gene | |

| MR80–5 | 17 | F | 53 | 40 | Moderate | dysmorphism | aka C9orf41 | |||

| MR80–6 | 15 | F | 49 | 40 | Moderate | |||||

| MR82 | MR82–3 | 17 | M | 50 | 45 | Moderate | Poor speech, seizures | ALG3 | AR congenital disorder of glycosylation type Id: seizures, craniofacial features, global developmental delay including ID | |

| MR82–4 | 15 | M | 49 | 45 | Moderate | |||||

| MR90 | MR90–5 | 18 | M | 53 | 40 | Moderate | Poor speech, seizures, depressive nature | TUSC3 | ARID with developmental delay, may include short stature, microcephaly, | |

| MR90–6 | 8 | F | 47 | 25 | Severe | Aggressive behavior | facial dysmorphism, congenital limb malformations | |||

| MR94 | MR94–5 | 9 | F | 40.5 | 20 | Severe | Microcephaly | ASPM | ARID with microcephaly and speech delay | |

| MR94–6 | 18 | M | 42.1 | 20 | Severe | |||||

| MR94–7 | 12 | F | 38.5 | 20 | Severe | |||||

| MR94–8 | 8 | F | 34.5 | 20 | Severe | |||||

| MR100 | MR 100–4 | 14 | F | 51 | 30 | Severe | Aggressive behavior, seizures | CACNG7 | Novel ARID gene | |

| MR 100–5 | 12 | M | 51 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MR 100–6 | 7 | M | 49 | 30 | Severe | None | ||||

| MR 106 | MR106–1 | 7 | M | 46 | 40 | Moderate | Developmental delay | CWF19L1 | ARID with spinocerebellar ataxia and atrophy | |

| MR106–4 | 13 | M | 50 | 42 | Moderate | Developmental delay, seizures, ataxia, cerebellar atrophy (MRI) | ||||

| MR 107 | MR107–1 | 20 | M | 53 | 30 | Severe | Aggressive behavior, poor speech | TRAPP CIO | Novel ARID gene | |

| MR107–2 | 26 | M | 50 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MR110 | MR110–1 | 6 | M | 38.5 | 32 | Severe | Microcephaly, high pain threshold | WDR62 | ARID with microcephaly and global developmental delay | |

| MR110–2 | 4 | F | 35 | 34 | Severe | Microcephaly | ||||

| MR110–3 | 7 | F | 40 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MR110–7 | 10 | F | 42 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MR115 | MR115–1 | 14 | M | 43.5 | 40 | Moderate | Microcephaly | ASPM | ARID with microcephaly and speech delay | |

| MR 115–2 | 11 | F | 43.5 | 40 | Moderate | |||||

| MR115–5 | 13 | M | 44.5 | 50 | Mild | |||||

| MR121 | MR121–1 | 13 | F | 41 | 25 | Severe | Microcephaly | PNKP | ARID with microcephaly, global developmental delay and seizures | |

| MR121–2 | 9 | M | 40 | 25 | Severe | |||||

| MR121–3 | 15 | F | 40 | 25 | Severe | |||||

| MR 123 | MR123–3 | 10 | M | 50 | 55 | Mild | None | CRADD | Mild ARID with developmental delay | |

| MR123–5 | 17 | M | 54 | 55 | Mild | |||||

| MR 124 | MR124–1 | 12 | M | 50 | 40 | Moderate | Slightly aggressive behavior, mild | LRP2 | (1) AR Donnai-Barrow syndrome with variable features: cerebrofacial and ocular anomalies, hearing loss, agenesis of the corpus callosum and ID; (2) mild ARID with delayed ambulation and speech and behavioral difficultiesb | |

| MR124–2 | 9 | M | 50.5 | 40 | Moderate | delay in ambulation | ||||

| MCP77 | MCP77A-3 | 15 | F | 47 | 30 | Severe | Microcephaly | WDR62 | AR microcephaly with global developmental delay | |

| MCP77A-5 | 12 | F | 45 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MCP77A-8 | 13 | F | 46 | 30 | Severe | |||||

| MCP77B-7 | 14 | M | 49 | 60 | Mild | Delayed ambulation and microcephaly | CYB5R3 | AR methemoglobinemia II with psychomotor retardation; may include microcephaly, ID, seizures, and cyanosis | ||

| MCP93 | MCP93–1 | 0.25 | M | 34 | NAC | NAC | Microcephaly | GARNLS | Novel gene for ARID with microcephaly | |

| MCP93–2 | 3 | M | 36 | 40 | Moderate | |||||

| MCP102 | MCP102–3 | 20 | M | 45.5 | 50 | Moderate | Microcephaly, poor speech, hyperactive behavior, unbalanced movement | BCKDK | AR branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase deficiency; variable phenotype including autism, epilepsy, intellectual disability and microcephaly | |

| MCP102–4 | 8 | F | 43 | 45 | Moderate | |||||

| MCP119 | MCP119–1 | 14 | M | 47 | 30 | Severe | Microcephaly | SPTBN2 | AR cerebellar ataxia with intellectual disability and pyramidal signs | |

| MCP119–2 | 12 | F | 45 | 30 | Severe | |||||

Within the mapped interval on 11q24.1-q25, a novel ST14 c.1718G > A (p.Arg573His) variant was identified to co-segregate with phenotypes in family 4699, including mild, diffuse dry scales particularly on the lower limbs. This ST14 variant has a scaled CADD score of 16.8, is predicted to be damaging by fathmm, metaLR, metaSVM and MutationTaster, and is rare in gnomAD (South Asian MAF = 0.0006, with two samples homozygous)

The LRP2 p.Asp3779Asn variant was previously reported to cause mild intellectual disability, delayed ambulation and speech, and behavioral difficulties in a multiplex Pakistani family (Vasli et al. 2016), which is similar to the moderate phenotype in family MR124 with the same LRP2 variant in this report

Undetermined due to young age (3 months)

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Quaid-i-Azam University and the Baylor College of Medicine and Affiliated Hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating members of 22 consanguineous families with AR neurodevelopmental diseases with ID that were ascertained from various regions of Pakistan (Fig. 1). The phenotypes of affected members of these pedigrees range from mild ID to syndromic ID with multiple features. For eight of the pedigrees all affected family members also display microcephaly (Table 1). Genome-wide genotyping was performed for all families. Twenty families were genotyped using the Infinium® HumanCoreExome Chip (Illumina, USA). For family MCP102 genotypes were generated using the Affymetrix 250K GeneChip® and for family AP51 genotyping was performed using 580 genome-wide short tandem repeat (STR) markers. Genotype data were analyzed using homozygosity mapping [HomozygosityMapper (Seelow et al. 2009)] and parametric multipoint linkage analysis [Allegro (Gudbjartsson et al. 2005)]. Parametric linkage analysis was performed using an autosomal recessive inheritance model with complete penetrance and no phenocopies and a disease allele frequency of 0.001. Marker allele frequencies were estimated using genotypes of founders and reconstructed founders of families genotyped using the same array. For multipoint linkage analysis genetic map positions were obtained through interpolation using the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map (NCBI GRCh37/hg19; Matise et al. 2007).

For 21 families, a DNA sample from one affected individual underwent exome sequencing. Because intra-familial locus heterogeneity (Rehman et al. 2015) was detected through homozygosity mapping and linkage analysis of whole-genome genotype data for family MCP77, DNA samples from two affected family members underwent exome sequencing. For all families, sequence capture was performed in solution with the Roche NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v.2.0 (~ 37 Mb target) at median read depth of 77X. Fastq files were aligned to the hg19 human reference sequence using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (Li and Durbin 2009). Realignment of indel regions, recalibration of base qualities, and variant detection and calling were performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK; McKenna et al. 2010) to produce variant call format (VCF) files, which were then annotated using ANNOVAR (Wang et al. 2010) and dbNSFP v2.9 (Liu et al. 2016). Rare damaging exome variants were selected for further segregation testing if they had: (A) a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.001 in all ancestry groups within the gnomAD database and (B) a scaled C-score of ≥ 10 in the combined annotation dependent depletion (CADD) database (Kircher et al. 2014) and also a damaging result from at least one additional bioinformatics tool from dbNSFP. Additionally, the rare damaging exome variant must co-segregate with ID phenotype which is verified by Sanger sequencing using DNA samples from all available family members. If a potentially causal variant in a previously published ID gene was not identified within a mapped region, we also tested for co-segregation with the phenotype rare damaging homozygous, potentially compound heterozygous and X-linked variants that were identified in the exome data outside of the linkage region. In addition to obtaining MAFs from gnomAD, the rarity of each variant in the Pakistani population was also verified by examining its occurrence in all in-house exome data from 194 Pakistani families with non-cognitive Mendelian traits, and examining its occurrence in the Greater Middle East (GME) Variome Project of 1,111 unrelated individuals, which includes 168 Persian/Pakistani individuals (Scott et al. 2016).

Using the ToppGene Suite (Chen et al. 2009) the seven newly identified genes (CACNG7, CARNMT1, EI24, GARNL3, FXR1, TRAPPC10, TET3) and two replicated ID candidate genes (GRAMD1B and TBRG1) were compared to 1948 human ID genes from the SysID database to query functional similarity and interaction with known ID genes. Network analysis was also performed via the InnateDB database (Breuer et al. 2013) within the NetworkAnalyst platform (Xia et al. 2014) using the 1,948 human ID genes from SysID and the genes identified in this study as input.

For all 23 genes with segregating rare variants, expression data were downloaded from the BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain (Miller et al. 2014) and from the Allen Human Brain Atlas for adult brain data (Hawrylycz et al. 2012). For adult brain data, if multiple probes were used for a gene, the median of the normalized expression values across probes for the same gene were used for analyses. A detailed description of the methods for normalizing the expression data is described elsewhere (Hawrylycz et al. 2012; Miller et al. 2014). For each gene, analysis of repeated measures was performed using ANOVA and Tukey’s range test to determine differential expression by top-level brain structure [i.e. 27 brain structures in total for which the ontology was derived from the Allen Human Brian Atlas (Hawrylycz et al. 2012)]. Since multiple comparisons were performed across multiple brain regions from the same individuals, a post-hoc Tukey’s range/honestly significant difference (HSD) test that uses the family-wise error rate for multiple testing correction was performed to evaluate where the differences detected by ANOVA testing lie. In addition a p value threshold of 0.0022 was used to correct for testing for 23 genes using the Bonferroni method. Finally for all 23 genes the genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) database was searched for significant expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) affecting specific brain regions from adult donor tissue (The GTEx Consortium 2013).

Results

Of the 22 families, eleven have severe ARID (Table 1). Eight of the 22 families (36.4%) have microcephaly that was identified in all affected family members. Additional features observed in the 22 families include poor speech (8 families), delayed ambulation or muscle tone defects (6 families), behavioral/mood changes (6 families), seizures (4 families), facial dysmorphism (1 family), ataxia with general developmental delay (1 family) or high pain threshold (1 family) (Table 1). In family 4699, multiple neurologic phenotypes such as limb spasticity, poor speech, inability to walk or stand, hearing impairment and ptosis were observed in all individuals with ARID and are likely due to the same variant in EI24 (Table 2), however, there was also mild ichthyosis that is probably due to a homozygous ST14 missense variant (Table 1; Neri et al. 2016).

Table 2.

Variants in two replicated and seven potentially novel candidate ARID genes identified in eight Pakistani families with syndromic and non-syndromic intellectual disability

| Gene | Novel candidate | Replicateda | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CACNG7 | CARNMT1 | EI24 | FXR1 | GARNL3 | TET3 | TRAPPC10 | GRAMD1B | TBRG1 | |

| Family | MR100 | MR80 | 4699 | AP51 | MCP93 | MR72 | MR107 | MR60 | MR60 |

| LOD score (θ = 0) | 2.53 | 2.53 | 3.26 | NAb | 1.93 | 2.53 | 2.06 | 2.66 | 2.66 |

| Mapped region | 19q13.41–q13.43 | 9q21.13 | 11q24.1–q25 | 3q26.2–q32.2 | 9q31.3–q34.12 | 2p13.3–p12 | 21q22.2–q22.3 | 11q23.2–q24.2 | 11q23.2–q24.2 |

| Gene region | 19q13.42 | 9q21.13 | 11q24.2 | 3q26.33 | 9q33.3 | 2p13.1 | 21q22.3 | 11q24.1 | 11q24.2 |

| hg19 Position | 54,445,503 | 77,642,928 | 125,451,175 | 180,693,986 | 130,097,608 | 74,314,999 | 45,509,730 | 123,465,484 | 124,496,836 |

| Reference allele | A | C | C | T | A | G | C | C | G |

| Alternate allele | G | T | T | A | G | T | T | T | A |

| MIM # | 606899 | 616552 | 605170 | 600819 | NA | 613555 | 602103 | NA | 610614 |

| mRNA accession (NM_#) | 031896.4 | 152420.1 | 004879.3 | 005087.3 | 032293.4 | 001287491.1 | 003274.4 | 020716.1 | 032811.2 |

| dbSNP rsID | rs778171763 | NA | NA | rs754901294 | rs764279982 | rs1227643933 | NA | NA | rs758546717 |

| cDNA change | c.784A > G | c.230G > A | c.742C > T | c.1772T > A | c.869A > G | c.2722G > T | c.2786C > T | c.382C > T | c.628G > A |

| Predicted effect | p.Ile262Val | p.Gly77Asp and splicing | p.Pro248Ser and splicing | p.Ile591Asn and splicing | p.Gln290Arg and splicing | p.Val908Leu and splicing | p.Pro929Leu | p.Arg128* | p.Ala210Thr and splicing |

| gnomAD South Asian Alleles | 26 het, 1 hom | 0 | 0 | 3 het | 10 het | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 het |

| gnomAD South Asian MAF | 0.0009 | 0 | 0 | 0.000098 | 0.0003 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0001 |

| gnomAD All MAF | 0.0001 | 0 | 0 | 0.00001 | 0.00004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00001 |

| GERP score | 4.21 | 5.25 | 5.26 | 3.93 | 5.16 | 4.7 | 4.88 | 5.6 | 2.77 |

| PhastCons | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PhyloP | 1.09 | 3.96 | 7.06 | 3.11 | 8.46 | 9.55 | 7.11 | 5.94 | 4.76 |

| CADD score | 18.8 | 21.5 | 22.4 | 23.7 | 22.0 | 28.2 | 35.0 | 22.4 | 23.0 |

| Bioinformatics tools with damaging results | MT | LRT, MTc | LRT, MA, MT, PR, SI | MT | Fa, LRT, mLR, MA, MT, PP2, PR, SI, mSVM | LRT, MA, MT, PP2, PR, SI | LRT, MT, PP2, PR, SI | MTd | MTc |

Conservation scores and bioinformatics results as compiled by dbNSFP v2.9. All variants were absent in 194 unrelated Pakistani exomes with non-cognitive Mendelian phenotypes and from the filtered dataset of ~ 1000 unrelated individuals from the Greater Middle East (GME) Variome Project, which includes 168 Persian/Pakistani individuals

NA not available, het heterozygous, hom homozygous, MAF minor allele frequency, CADD combined annotation dependent depletion, MT MutationTaster, LRT likelihood ratio test, MA MutationAssessor, PR PROVEAN, SI SIFT, Fa Fathmm, mLR meta-logistic regression, PP2 Polyphen- 2 HVAR, mSVM meta-support vector machine

A GRAMD1B missense variant was previously identified in a single consanguineous Syrian family with moderate nonsyndromic ID (Reuter et al. 2017). Additionally a TBRG1 frameshift variant was identified in a single consanguineous Persian family with severe ARID and severe developmental delay including motor and speech abnormalities (Hu et al. 2018)

Parents are known to be related but exact relationships are unknown, thus linkage analysis was not performed. The mapped region is from homozygosity mapping

Benign by PolyPhen-2 HVAR but possibly damaging by PolyPhen-2 HDIV

Predicted to initiate nonsense-mediated decay

A total of 25 homozygous variants were identified to co-segregate with ARID in 22 families (Tables 1, 2, 3; Fig. 1) in either known or novel candidate ARID genes. Seven families have homozygous variants in potentially novel candidate genes for ARID (CACNG7, CARNMT1/C9orf41, EI24, GARNL3, FXR1, TRAPPC10, TET3; Tables 1, 2). One additional family MR60 with severe ARID has a homozygous stop variant in GRAMD1B and a rare, damaging mis-sense variant in TBRG1, both of which lie within the mapped region in chromosome 11q23.2-q24.2 and were previously suggested to be candidate genes for ARID (Reuter et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2018) having been identified in a single ARID family (Table 2). Both replicated ID genes are likely to be sufficient to cause disease etiology but no conclusion can be made on the impact on the phenotype of being a homozygous carrier for variants in both genes.

Table 3.

16 Variants in 14 Known ARID Genes Identified in 14 Pakistani Families with Syndromic and Non-Syndromic Intellectual Disability

| Gene | ALG3 | ASPM | ASPM | BCKDK | CRADD | CWF19L1 | CYB5R3 | GAN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | MR82 | MR94 | MR115 | MCP102 | MR123 | MR106 | MCP77Bb | MR61 | ||||||

| LOD score (θ = 0) | 1.81 | 3.26 | 2.53 | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.23 | 0.92 | 2.06 | ||||||

| Mapped region | 3q26.31–q27.3 | 1q25.2–q32.1 | 1q24.1–q32.1 | 16p11.2 | 12q12.31–q22 | 10q23.31–q26.13 | 22q11.22–q13.33 | 16q23.1–q24.1 | ||||||

| Gene region | 3q27.1 | 1q31.3 | 1q31.3 | 16p11.2 | 12q22 | 10q24.31 | 22q13.2 | 16q23.3 | ||||||

| hg19 position | 183,961,398 | 197,060,124 | 197,059,469 | 31,122,009 | 94,072,833 | 102,005,571 | 43,024,184 | 81,396,185 | ||||||

| Reference allele | G | A | AT | CCTGA | A | G | C | A | ||||||

| Alternate allele | A | C | A | C | AC | A | G | G | ||||||

| MIM # | 608750 | 605481 | 605481 | 614901 | 603454 | 616120 | 613213 | 256850 | ||||||

| NM_# | 005787.5 | 018136.4 | 018136.4 | 005881.3 | 003805.3 | 018294.4 | 001171660.1 | 022041.3 | ||||||

| dbSNP rsID | rs756802179 | rs143931757 | rs199422192 | NA | rs762622157 | NA | NA | rs779203584 | ||||||

| cDNA change | c.953C > T | c.2492T > Gc | c.9685delA | c.644_647delCTGA | c.283_284insC | c.949C > T | c.536G > C | c.1055A > G | ||||||

| Predicted effect | p.Ser318Leu | p.Tyr3164* | p.Ile3229Leufs*6 | p.Asp216Leufs*65 and splicing | p.Asp96Argfs*6 | p.Gln317* and splicing | p.Ser179Thr and splicing | p.Asn352Ser and splicing | ||||||

| Novel varianta | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| gnomAD South Asian alleles | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 het | 0 | 0 | 1 het | ||||||

| gnomAD South Asian MAF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00007 | 0 | 0 | 0.00003 | ||||||

| gnomAD All MAF | 0.00001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000008 | 0 | 0 | 0.000008 | ||||||

| GERP Score | 5.64 | − 0.69 | NA | NA | NA | 5.78 | 3.92 | 5.04 | ||||||

| PhastCons | 1 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | ||||||

| PhyloP | 5.37 | 0.31 | NA | NA | NA | 6.06 | 3.63 | 8.09 | ||||||

| CADD Score | 19.75 | 36.0 | NA | NA | NA | 22.5 | 16.4 | 23.9 | ||||||

| Damaging results | Fa, mLR, MT, mSVM | MTh | MTh | MTh | MT | LRT, MTh | Fa, LRT, mLR, MT | Fa, LRT, mLR, MA, MT, PP2, SI, mSVM | ||||||

| Gene | LRP2 | MBOAT7 | MLYCD | PNKP | SPTBN2 | TUSC3 | WDR62 | WDR62 | ||||||

| Family | MR124 | MR77 | MR61 | MR121 | MCP119 | MR90 | MR110 | MCP77Ab | ||||||

| LOD score (θ = 0) | 1.88 | 3.21 | 2.06 | 2.53 | NAd | 2.06 | 5.32 | 1.62 | ||||||

| Mapped region | 2q31.1 | 19q13.33-q13.42 | 16q23.1-q24.1 | 19q13.32-q13.33 | 11q12.3-q13.2 | Not in a mapped regiong | 19q12-q13.2 | 19p13.11-q13.2 | ||||||

| Gene region | 2q31.1 | 19q13.42 | 16q23.3 | 19q13.33 | 11q13.2 | 8p22 | 19q13.12 | 19q13.12 | ||||||

| hg19 position | 170,027,106 | 54,691,124 | 83,948,669 | 50,369,653 | 66,461,669 | 15,531,261 | 36,593,872 | 36,587,986 | ||||||

| Reference allele | C | CA | G | T | G | A | CG | G | ||||||

| Alternate allele | T | C | GA | TA | A | G | C | T | ||||||

| MIM # | 600073 | 606048 | 606761 | 605610 | 604985 | 601385 | 613583 | 613583 | ||||||

| NM_# | 004525.2 | 024298.3 | 012213.2 | 007254.3 | 006946.2 | 006765.3 | 001083961.1 | 001083961.1 | ||||||

| dbSNP rsID | rs199583537 | NA | NA | NA | rs373270554 | rs773936260 | NA | rs754976942 | ||||||

| cDNA change | c.11335G > Ae | c.251delT | c.1057_1058insA | c.198 + 2_+3insT | c.4444C > Tf | c.714A > Gg | c.3359delG | c.2520 + 5G > T | ||||||

| Predicted effect | p.Asp3779Asn | p.Leu84Argfs*25 and splicing | p.Leu354Thrfs*8 and splicing | Splicing | p.Arg1482Trp and splicing | p.Ile238Met and splicing | p.Ala1121Gl- nfs*6 and splicing | Splicing | ||||||

| Novel varianta | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||||||

| gnomAD South Asian alleles | 20 het | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 het, 1 hom | 12 het | 0 | 1 het | ||||||

| gnomAD South Asian MAF | 0.0006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | 0 | 0.00003 | ||||||

| gnomAD All MAF | 0.0002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0.00005 | 0 | 0.000004 | ||||||

| GERP score | 5.86 | NA | NA | NA | 2.53 | − 0.11 | NA | 4.92 | ||||||

| PhastCons | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0.99 | NA | 1 | ||||||

| PhyloP | 4.98 | NA | NA | NA | −0.02 | 0.45 | NA | 6.41 | ||||||

| CADD score | 26.2 | NA | NA | NA | 26.2 | 25.4 | NA | 12.9 | ||||||

| Damaging results | MT | MTh | MA, MTh, PP2, PR, SI | MT | MT | MT, PP2, PR, SI | LRT, MTh, PP2, SI | MT | ||||||

Abbreviations as in Table 2. Unless indicated, these variants were absent in 194 unrelated Pakistani exomes with non-cognitive Mendelian phenotypes and in ~ 1000 unrelated individuals in the GME Variome Project. References per known gene: ALG3 (Riess et al. 2013); ASPM (Kousar et al. 2010); BCKDK (Novarino et al. 2012); CRADD (Di Donato et al. 2016; Harel et al. 2017); CWF19L1 (Burns et al. 2014; Nguyen et al. 2016; Evers et al. 2016); CYB5R3 (Ewenczyk et al. 2008); GAN (Kuhlenbäumer et al. 2002; Tazir et al. 2009); LRP2 (Vasli et al. 2016); MBOAT7 (Johansen et al. 2016); MLYCD (Salomons et al. 2007); PNKP (Shen et al. 2010); SPTBN2 (Lise et al. 2012); TUSC3 (Garshasbi et al. 2008, 2011; Khan et al. 2011; Loddo et al. 2013; Al-Amri et al. 2016); WDR62 (Wang et al. 2017).

All variants except the CYB5R3 variant are classified as pathogenic according to ACMG guidelines (Richards et al. 2015). Novel pathogenic variants are in bold font.

Family MCP77 showed evidence of intra-familial genetic heterogeneity based on mapping data. The LOD scores shown in the Table are based on the pedigree split by sibships and using genome-wide genotype data. A DNA sample from an affected individual from each branch A and B was submitted for exome sequencing. Branch B has only one affected individual who is homozygous for the CYB5R3 variant while an affected sib is homozygous for the WDR62 splice variant (Fig. 1). Thus, the LOD score for the CYB5R3 variant is 0.92, while the LOD score for the WDR62 splice variant is 2.78. Based on the ACMG guidelines the CYB5R3 variant is classified as a variant of unknown significance.

This ASPM variant was reported heterozygous in 4 individuals of 993 unrelated individuals in the GME Variome Project, but was absent in gnomAD.

Parents are known to be related but exact relationships are unknown, thus linkage analysis was not performed. The mapped region is from homozygosity mapping.

This LRP2 variant was reported heterozygous in 3 of 993 unrelated individuals in the GME Variome Project.

This SPTBN2 variant was heterozygous in one exome from an individual with an unrelated phenotype.

This TUSC3 variant was reported heterozygous in 1 of 992 unrelated individuals in the GME Variome Project. The TUSC3 gene does not lie within any mapped region for this family because the markers surrounding TUSC3 were uninformative for linkage.

Predicted to initiate nonsense-mediated decay

Fourteen families have homozygous variants in genes previously shown to be involved in ARID or a phenotype which included ID (Table 3). Two of these families each have homozygous variants in two previously reported ID genes. For one of these families MCP77 there is locus and phenotypic heterogeneity: one branch with severe ID and micro-cephaly segregates a WDR62 variant, while the branch with mild ID and microcephaly has a CYB5R3 variant (Fig. 1; Table 3). Family MR61 segregates variants in both GAN and MLYCD which are well-established for their involvement in ID (Fig. 1; Table 1), and being a carrier of homozygous variants in one of these genes is sufficient to cause ARID thus it is not possible to conclude with our data whether or not segregating both genes contributes to a more severe phenotype. Two families (MR94 and MR115) have two different known pathogenic variants in ASPM and two families (MR110 and MRP77A) each have a novel and a known pathogenic variant in WDR62 (Table 3). For the known ARID genes all variants, including the 11 newly identified variants, can be classified as pathogenic according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines (Richards et al. 2015), with the exception of the novel variant in CYB5R3 which is a variant of unknown significance. An additional five homozygous variants which co-segregate with ID were also observed but have weaker evidence of involvement in ID etiology (Supplementary Table 1). Due to the lack of evidence, it is not clear whether or not these five variants contribute to the ID phenotype in the five families. For four of the families, another rare damaging homozygous variant in a gene established to be involved in ARID etiology co-segregates with ID. For family AP51, homozygous exome variants in FXR1 and HRG were identified within the same mapped region on 3q26.2-q32.3, and co-segregated with ID (Table 2; Supplementary Table 1). However, due to the strong evidence of a role for FXR1 in ID it is likely that this gene underlies ARID in family AP51. FXR1 belongs to the fragile X gene family that is associated with autistic phenotypes (Stepniak et al. 2015) and the mouse model showed a regulatory role of Fxr1 in brain (Xu et al. 2011).

For the 21 families for which linkage analysis was performed, LOD scores for these variants ranged from 0.92 to 5.24 (Tables 2, 3) which were the maximum LOD scores that can be achieved for each pedigree structure (Fig. 1). The nine replicated or novel candidate genes and the known ARID genes all lie within regions of linkage and homozygosity, with the exception of a homozygous variant in known ARID gene TUSC3 which does not lie within a mapped region for family MR90 (Table 3). For family MR90, the region surrounding the TUSC3 gene contained markers that were uninformative, thus the genomic region encompassing TUSC3 was not identified by linkage analysis nor homozygosity mapping. In the eight families which segregate variants in novel and replicated candidate ARID genes the homozygous variants all lie within the mapped regions (Table 2). In these eight families all rare damaging homozygous and potentially compound heterozygous variants identified in the exome sequence data were Sanger-sequenced in all family members. This was done to evaluate whether or not they co-segregated with the ARID phenotype, but none of the variants outside of the mapped regions co-segregated with ARID (Table 2). For two families, MCP119 and AP51, the exact consanguineous relationship of the parents is unknown (Fig. 1), and only homozygosity mapping was performed (Tables 2, 3).

Each of the 23 known and novel candidate genes were highly expressed in specific brain structures within different time intervals: all 23 genes demonstrate differential expression and harbor significant eQTLs in specific tissues of adult brain while 74% of the genes demonstrate differential expression in utero (Table 4). GRAMD1B, TBRG1 and all seven novel candidate ARID genes are expressed in the brain prenatally or during early childhood (Table 4). These genes are either highly ranked as candidate genes by ToppGene or interact with protein products of known ID genes based on analysis using ToppNet (Supplementary Table 2) and NetworkAnalyst (Supplementary Fig. 1). Network analysis identified proteins encoded by one replicated and three out of the seven novel candidate genes for ARID, i.e. TBRG1, FXR1, TRAPPC10 and TET3, as interacting proteins within a large network of brain proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Expression of 23 genes in the developing and adult human brain and GTEx brain tissues with gene-specific expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs)

| Genea | Structure identified in developmental transcrip- tome | Age intervals with differential expressionb | Structures with differential expression in adult brain by top-level structure (24–57 y)c | GTEx brain tissue with significant singletissue eQTLs (ordered by increasing p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALG3 | Thalamus | 1–3 y, 23–30 y, 37–40 y | Sulci and spaces, cerebellar nuclei, subthalamus, dorsal thalamus, mesencephalon, myelencephalon, pontine tegmentum, ventral thalamus | Caudate (basal ganglia) |

| ASPM | Allocortex | 9–12 pew, 2–3 y | Parietal lobe, occipital lobe, temporal lobe, frontal lobe | Frontal cortex |

| BCKDK | Thalamus, basal nuclei | 13–16 pew, 35–37 pew, 4–10 m, 2–13 y, 18–19 y, 23–40 y | Striatum, cerebellar cortex, amygdala, frontal lobe, epithalamus | Cerebellar hemisphere |

| CACNG7 | Neural plate | 8–9 pew, 11–13 y | Occipital lobe, parietal lobe, frontal lobe, temporal lobe | Cerebellar hemisphere |

| CARNMT1 IC9orf41 | Thalamus, basal nuclei | 1–2 y | Striatum, cerebellar cortex | Cerebellum, cerebellar hemisphere, anterior cingulate cortex, putamen (basal ganglia) |

| CRADD | Neural plate | 8–9 pew, 3–8 y, 37–40 y | Sulci and spaces, claustrum, dorsal thalamus, ventral thalamus | Cerebellum |

| CWF19L1 | Thalamus | 19–21 pew, 37 pcw-4 m, 3–4 y, 8–11 y, 36–40 y | Cerebellar cortex, hippocampal formation | Cortex, cerebellum, caudate/nucleus accum- bens (basal ganglia), anterior cingulate cortex, frontal cortex, cerebellar hemisphere, putamen (basal ganglia), hypothalamus, hippocampus, substantia nigra, amygdala |

| CYB5R3 | Allocortex | 8–13 y, 30–36 y | Myelencephalon, pontine tegmentum, cerebellar nuclei | Cerebellum, putamen/nucleus accumbens (basal ganglia), cerebellar hemisphere, anterior cingulate cortex, frontal cortex, cortex |

| EI24 | Basal nuclei | 1–3 y, 8–13 y | Frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe | Hippocampus, cerebellar hemisphere |

| FXR1 | Allocortex | 12–13 pew, 1–3 y | White matter, hypothalamus, mesencephalon, cerebellar nuclei, dorsal thalamus, myelencephalon, pontine tegmentum | Hypothalamus, cortex |

| GAN | Thalamus | 16–17 pew, 10 m-2 y, 4–8 y, 21–30 y | Epithalamus, pontine tegmentum, globus pallidus, myelencephalon | Cerebellum |

| GARNL3 | Basal nuclei, neural plate | 9–12 pew, 1–2 y, 4–8 y | Cerebellar cortex | Cortex |

| GRAMD1B | Basal nuclei | 8–9 pew, 13–16 pew, 19–37 pew, 4 m-3 y, 4–11 y, 15–19 y, 37–40 y | White matter, hypothalamus, cerebellar cortex, hippocampal formation | Cerebellar hemisphere, cortex, cerebellum |

| LRP2 | Ventricular zone | 18–19y | Ventral thalamus, white matter, globus pallidus, myelencephalon, cerebellar nuclei, dorsal thalamus, mesencephalon | Putamen (basal ganglia) |

| MBOAT7 | Basal nuclei | 16–17 pew, 18–19 y | Hippocampal formation, basal part of pons, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, dorsal thalamus, frontal lobe, myelencephalon, temporal lobe | Amygdala |

| MLYCD | Thalamus | 9–12 pew, 1–3 y, 18–19 y, 37–40 y | Globus pallidus, subthalamus, dorsal thalamus, white matter | Caudate (basal ganglia) |

| PNKP | Basal nuclei | 10 m-1 y | Sulci and spaces, myelencephalon, subthalamus, dorsal thalamus, ventral thalamus | Cortex, frontal cortex, caudate (basal ganglia), anterior cingulate cortex, cerebellum, nucleus accumbens (basal ganglia), hippocampus |

| SPTBN2 | Neural plate | 21–24 pew, 37 pcw-4 m, 1–2 y, 11–13 y, 30–36y | Hippocampal formation, cerebellar cortex, occipital lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe | Hypothalamus |

| TBRG1 | Allocortex, basal nuclei | 12–13 pew, 37 pcw-4 m, 10 m-3 y, 11–13 y, 15–19y | Striatum, myelencephalon, frontal lobe, occipital lobe, temporal lobe, dorsal thalamus | Cerebellar hemisphere |

| TET3 | Thalamus | 16–17 pew, 21–24 pew, 1–2 y | Cerebellar cortex | NA; highest median TPM in cerebellar hemisphere, cerebellum |

| TRAPPC10 | Thalamus | 17–21 pew, 24–25 pew, 10 m-3 y, 18–19 y, 37–40 y | White matter, ventral thalamus, claustrum | Cerebellum, cerebellar hemisphere |

| TUSC3 | Basal nuclei | 24–25 pew, 26–35 pew, 1–4 y, 11–13 y, 15–19y | Sulci and spaces, hypothalamus, striatum | Cerebellum, cerebellar hemisphere, caudate (basal ganglia) |

| WDR62 | Thalamus, ventricular zone | 9–12 pew, 35–37 pew | White matter, cerebellar cortex | Cortex, frontal cortex, cerebellum |

Novel candidate and replicated genes in bold font

y years, m months, pcw post-conceptional weeks

Except for FXR1 (p = 0.04), all other genes have Tukey HSD p < 2 × 10−6, which is lower than the p value threshold of 0.0022 that is corrected using the Bonferroni method for performing the same test on the same dataset for 23 genes

Discussion

We studied 22 consanguineous Pakistani families with a spectrum of ARID disorders including some families with microcephaly. We also potentially replicated two candidate ARID genes and found novel rare variants that co-segregate with disease. We identified seven novel candidate ARID genes, CACNG7, CARNMT1/C9orf41, EI24, FXR1, TET3, GARNL3 and TRAPPC10, for which evidence of their contribution to the corresponding ARID phenotype is strong (Table 5). For novel genes EI24, FXR1 and TET3 a role in ARID is strongly supported by observations in previously published knockout mouse models: Ei24−/− and Tet3−/− mice demonstrate defects in brain morphology, neuronal differentiation and/or behavior and motor development, while the Fxr1 knockout results in early death, with lower brain miRNA expression in Fxr1−/− embryos (Zhao et al. 2012; Zhu et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2011; Table 5). Cell-based functional experiments for CACNG7 and TRAPPC10, which are highly expressed in brain specifically in the cerebellum (Table 4), also suggest the involvement of these genes in ARID pathogenesis (Table 5). CACNG7 plays a role in stabilizing expression of calcium channels (Ferron et al. 2008). TRAPPC10 forms part of a transport complex for endocytosis or secretion, and binds TRAPPC9 which is also involved in the etiology of ID and microcephaly (Mir et al. 2009; Mochida et al. 2009). Moreover, previously reported ID patients with dominant/de novo microdeletions that encompass either CARNMT1/C9orf41 or GARNL3 (Boudry-Labis et al. 2013; Baglietto et al. 2014; Ehret et al. 2015) exhibited phenotypes (i.e. facial dysmorphisms for CAR NMT1 and microcephaly for GARNL3) that are similar to those observed for families MR80 and MCP93 which have variants in these two genes (Table 1). Both C9orf41 and GARNL3 are differentially expressed in developing basal nuclei and in adult cerebellar cortex in humans (Table 4).

Table 5.

Published literature on two replicated and seven novel candidate genes for syndromic and non-syndromic intellectual disability

| Novel gene | Known from previous studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| CACNG7 | The two transcripts of CACNG7 are expressed only in brain. Coexpression of the γ7 subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel almost abolished N-type current through Cav2.2, while γ7-knockdown results in enhanced stability of Cav2.2 expression | Moss et al. (2002), Ferron et al. (2008) |

| CARNMT1/C9orf41 | C9orf41 is a carnosine N-methyltransferase that is expressed in human kidney, brain and skeletal muscle. C9orf41 is one of four genes included in a de novo 9q21.13 microdeletion that caused mild intellectual disability, epilepsy and mild facial dysmorphism in a 12-year old patient | Drozak et al. (2015), Baglietto et al. (2014) |

| EI24 | Ei24-deficient mice showed behavioral and motor defects starting at 6 weeks of age. Brain abnormalities include enlarged lateral ventricles, cortical atrophy, thinner white matter and cortical cell layers, progressive axonal degeneration and massive neuronal loss | Zhao et al. (2012) |

| FXR1/FXR1P | FXR1, a RNA binding protein that is associated with genetic risk for schizophrenia, is phosphorylated and downregulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β, which is inhibited by psychoactive drugs to regulate behavior. FXR1 is strongly expressed in neuronal nuclei. Fxr1 knockout mice die shortly after birth. In fxr1 knockout embryos, expression of miR-124 and miR-9 are lower, suggesting that Fxr1 regulates brain miRNA levels | Stepniak et al. (2015), Bakker et al. (2000), Del’Guidice et al. (2015), Tamanini et al. (1997), Mientjes et al. (2004), Xu et al. (2011) |

| GARNL3 | In five patients with 9q33.3–q34.11 microdeletions and intellectual disability, the smallest region of overlap includes only two genes, RALGPS1 and GARNL3. Four out of five patients have microcephaly. Other features include short stature, facial dysmorphisms, strabismus, muscular hypotonia, and variably delayed speech or ambulation | Ehret et al. (2015) |

| GRAMD1B | A missense variant GRAMD1B c.565C > T (p.Arg189Trp) was identified to co-segregate with moderate ID in a consanguineous Syrian family | Reuter et al. (2017) |

| TBRG1/NIAM | NIAM has low expression in brain and NIAM mRNA levels are further reduced in brain cancer. Silencing of NIAM accelerated chromosomal instability. A Niamm/m mouse model had 70% reduction of NIAM protein in brain, although specific brain tissue or behavioral changes were not reported. TBRG1 expression is upreg- ulated in pigs with abnormal tail biting behavior (biter or receiver of bites). A frameshift variant TBRG1 c.198dup (p.Leu67Serfs*2) was identified to co-segregate with severe ID with severe developmental delay in a consanguineous Persian family | Tompkins et al. (2007), Reed et al. (2014), Brunberg et al. (2013), Hu et al. (2018) |

| TET3 | Tet3 is most highly expressed in brain cortex, and its expression is upregulated during neuronal differentiation. Tet3 overexpression resulted in early neuronal differentiation while reduced Tet3 expression led to defects in neuronal differentiation. Tet3 knockdown also inhibited dendritic arborization of cerebellar granule cells which is required for circuit formation. Additionally Tet3 is important for maintenance of neural progenitor cells (NPC). Human TET3 antibodies localized to the nuclei of differentiating oligodendrocytes. In mouse neuronal brain cells Tet3 is localized at transcription start sites of genes involved in lysosome function, mRNA processing and genes of the base excision repair pathway. Epigenetic regulation of NPC maintenance is mediated by TET3 interactions with MCPIP1, miR-15b and EN-2. In primary cortical neurons and the prefrontal cortex, Tet3 expression is dependent on learning activity such as fear extinction conditioning and is necessary for rapid behavioral adaptation | Hahn et al. (2013), Zhu et al. (2016), Li et al. (2015), Zhao et al. (2014), Jin et al. (2016), Jiang et al. (2016), Lv et al. (2014), James et al. (2014), Li et al. (2014) |

| TRAPPC100 | TRAPPC10, TRAPPC9 and TRAPPC2 are part of the same transport protein particle complex that is involved in secretory and endocytic pathways. TRAPPC2 binds to TRAPPC9, which in turn binds to TRAPPC10. TRAPPC9 mutations cause postnatal intellectual disability with or without microcephaly. If mutated, TRAPPC9 fails to interact with TRAPPC2 and TRAPPC10 | Mir et al. (2009), Mochida et al. (2009), Zong et al. (2011) |

Family MR60 has two novel rare variants, a GRAMD1B nonsense variant and a TBRG1 missense variant, both within the same mapped interval at 11q23.2-q24.2 and co-segregating with severe ARID (Tables 1, 2). In a previous publication a missense variant within GRAMD1B was identified in a consanguineous Syrian family with moderate nonsyndromic ID (Reuter et al. 2017). On the other hand, a consanguineous Persian family was found to have a frameshift TBRG1 variant co-segregating with severe ARID and developmental delay (Hu et al. 2018). Two out of three affected siblings from family MR60 have severe nonsyndromic ID, but one affected sibling has severe ID with psychomotor delay (Table 1). Therefore, in this family, although it is possible that only one of these two variants underlie ARID, it is more likely that both variants are pathogenic. Tbrg1−/− knockout mice have reduced protein expression in brain (Reed et al. 2014), while in a pig model with abnormal behavior TBRG1 expression is upregulated (Brunberg et al. 2013). Not much is known about the function of GRAMD1B in brain, except that it is differentially expressed in cerebellar cortex in the adult human brain and in basal nuclei during development (Table 4).

We identified 16 homozygous variants in 14 genes that have been previously reported to underlie ARID with or without microcephaly and/or other features, of which 11 (69%) are novel (Table 3). Notably the majority (62.5%) of these 16 variants are loss-of-function (i.e. stop, frameshift, splice; Table 3). Most of these genes have been well-established as genes involved in ARID with or without micro-cephaly. In Pakistan, ASPM and WDR62 variants are the most common genetic causes of ARID with microcephaly (Sajid Hussain et al. 2013). In this study, of the eight families with ARID and microcephaly, four families have variants in either ASPM or WDR62 (Table 3).

A closer look at the phenotypes and variant data suggests that for some families (e.g. MR60 as discussed above, MCP77, MR61), multiple variants might be disease-causal or, at the least, cause some degree of phenotypic variability. Family MCP77 with ARID and microcephaly displayed intra-familial genetic heterogeneity with homozygous variants in ARID genes WDR62 and CYB5R3 in branches A and B, respectively (Fig. 1). Although CYB5R3 is a gene for a rare disease type II recessive hereditary methemoglobinemia, ID and microcephaly were always present in reviewed cases (Ewenczyk et al. 2008). Linkage analysis of whole-genome genotypes led to the suspicion of intra-familial locus heterogeneity in family MCP77, thus a DNA sample from an affected individual from each branch was submitted for exome sequencing, which revealed the WDR62 and CYB5R3 variants (Table 3). It must be noted that in branch B of MCP77, only one out of two affected individuals carry the CYB5R3 variant as homozygous and the other affected sibling is homozygous for the WDR62 variant (Fig. 1). Thus for family MCP77, there is not only intra-familial heterogeneity by branch but also intra-sibship genetic heterogeneity within the same branch, emphasizing that careful selection of samples for exome sequencing, possibly with the aid of haplotype information from genome-wide genotype data, is important to get to the correct causal variant (Rehman et al. 2015).

Family MR61 displays multi-genic inheritance, segregating two damaging variants in known ARID genes GAN and MLYCD, both of which lie within the mapped interval at 16q23.1-q24.1 (Table 3). Affected family members of MR61 have moderate ARID with no additional features except for aggressive behavior noted in one affected individual (Table 1). Variants in both GAN and MLYCD were previously observed to cause developmental delay, ID and additional disease features e.g. peripheral neuropathy, metabolic disease, that were not observed in family MR61 (Kuhlenbäumer et al. 2002; Tazir et al. 2009; Salomons et al. 2007). Interestingly both GAN and MLYCD have strongest expression in the thalamus during development (Table 4), and the thalamus has a proven role in both cognition and aggression (Fama and Sullivan 2015; Kumari et al. 2013).

A few of our families with known ARID genes show an atypical representation. The first atypical family is MR124, in which patients have moderate ID, slightly aggressive behavior, mild delay in ambulation and a homozygous LRP2 variant c.11335G > A (p.Asp3779Asn). The same LRP2 c.11335G > A (p.Asp3779Asn) variant was also reported in a multiplex Pakistani family which had a phenotype very similar to that of family MR124, i.e. mild ID, delayed ambulation and speech, and behavioral difficulties (Vasli et al. 2016). These features are milder than the phenotype for LRP2-related Donnai–Barrow syndrome, a multi-system disorder that includes unusual facial features, sensorineural hearing loss, vision problems, corpus callosum abnormalities, mild-to-moderate ID and developmental delay (Kantarci et al. 2007; Khalifa et al. 2015). Based on InterPro analysis, the LRP2 p.Asp3779Asn variant occurs at a highly conserved residue that participates in calcium-binding within an LDL receptor class A repeat domain. Our data support that LRP2 missense variants, in contrast to loss-of-function variants, result in a milder phenotype (Khalifa et al. 2015; Vasli et al. 2016). Second, family MCP119, which presents with ID and severe microcephaly, has a novel AR variant in SPTBN2 c.4444C > T (p.Arg1482Trp). The affected protein residue lies within a spectrum/alpha-actinin repeat close to a linker region, suggesting a role in protein structure. Variants in SPTBN2 typically cause AD and AR spinocerebellar ataxia with intellectual disability but not microcephaly (Lise et al. 2012). One report mentions relatively mild microcephaly in a child with cerebellar ataxia and developmental delay and a de novo SPTBN2 variant c.1438C > T (p.Arg480Trp) (Schnekenberg et al. 2015). The patients in family MCP119 have severe ARID with microcephaly but no signs of cerebellar ataxia, making their presentation atypical. For family MR106 with a CWF19L1 homozygous variant and family MR90 with a TUSC3 homozygous variant, seizures were observed in some family members. Seizure has not been previously reported as a feature of CWF19L1- and TUSC3-related ARID (Burns et al. 2014; Nguyen et al. 2016; Evers et al. 2016; Garshasbi et al. 2008, 2011; Khan et al. 2011; Loddo et al. 2013; Al-Amri et al. 2016). Interestingly TUSC3 belongs to the same gene family as ALG3, which is associated with congenital disorders of N-linked glycosylation that commonly include seizures as a feature (Table 1; Garshasbi et al. 2008; Sparks and Krasnewich 2017). Although seizures have not been reported as a feature of CWF19L1-related ARID and ataxia, seizures are common clinical findings in other genetic forms of autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia (Bird 2016). Taken together, the atypical presentation for these four families could be due to phenotypic variations associated with domain-specific variants in LRP2, SPTBN2, CWF19L1 and TUSC3.

This study further supports previous findings of phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity of ARID, as we found that each family segregates a different ID variant, only two known ID genes were detected twice, and intra-familial heterogeneity was also observed. We also corroborate the observation that many Mendelian forms of ID phenotypes are due to rare variants in a large spectrum of genes which are yet to be fully elucidated. Some of these genes might be unique to a family or extremely rare making replication difficult. The identification of these novel candidate genes and variants adds to the knowledge base that is required to further understand brain function and development in humans.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Web resources.

Allen Brain Atlas, http://human.brain-map.org/.

ANNOVAR, http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/.

BrainSpan, http://www.brainspan.org/.

Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion, http://cadd.gs.washington.edu/.

dbNSFP, http://sites.google.com/site/jpopgen/dbNSFP.

dbSNP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/Fathmm,fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/.

Genetic Variant Interpretation Tool, http://www.medschool.umaryland.edu/Genetic_Variant_Interpretation_Tool1.html.

Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/.

Greater Middle East (GME) Variome Project, http://igm.ucsd.edu/gme.

GTEx Portal, http://www.gtexportal.org.

HomozygosityMapper, http://www.homozygositymapper.org/.

InnateDB, http://www.innatedb.com/.

Interpro, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/.

Likelihood RatioTest, http://www.genetics.wustl.edu/jflab/lrt_query.html.

MutationAssessor, http://mutationassessor.org/r3/.

MutationTaster,http://www.mutationtaster.org/.

NetworkAnalyst, http://www.networkanalyst.ca/. Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man, http://www.omim.org/.

PolyPhen2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/. PROVEAN, http://provean.jcvi.org/.

Rutgers Combined Linkage-Physical Map, http://compgen.rutgers.edu/rutgers_maps.shtml.

SIFT, http://sift.jcvi.org/.

SysID, http://sysid.cmbi.umcn.nl/.

ToppGene Suite, http://toppgene.cchmc.org/.

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families who participated in this study. We also thank the following who provided genotyping and sequencing services at the University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics (UW-CMG): Michael J. Bamshad1,2, Suzanne M. Leal3, and Deborah A. Nickerson1; Peter Anderson1, Marcus Annable1, Elizabeth E. Blue1, Kati J. Buckingham1, Imen Chakchouk3, Jennifer Chin1, Jessica X Chong1, Rodolfo Cornejo Jr.1, Colleen P. Davis1, Christopher Frazar1, Martha Horike-Pyne1, Gail P. Jarvik1, Eric Johanson1, Ashley N. Kang1, Tom Kolar1, Stephanie A. Krauter1, Colby T. Marvin1, Sean McGee1, Daniel J. McGoldrick1, Karynne Patterson1, Sam W. Phillips1, Jessica Pijoan1, Matthew A. Richardson1, Peggy D. Robertson1, Isabelle Schrauwen3, Krystal Slattery1, Kathryn M. Shively1, Joshua D. Smith1, Monica Tackett1, Alice E. Tattersall1, Marc Wegener1, Jeffrey M. Weiss1, Marsha M. Wheeler1, Qian Yi1, and Di Zhang3; Affiliations—1University of Washington;2Seattle Children’s Hospital;3Baylor College of Medicine. UW-CMG was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant HG006493 (to D. Nickerson, M. Bamshad and S. Leal). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by funds from the Higher Education Commission, Islamabad, Pakistan (to W. Ahmad).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-018-1928-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Al-Amri A, Saegh AA, Al-Mamari W et al. (2016) Homozygous single base deletion in TUSC3 causes intellectual disability with developmental delay in an Omani family. Am J Med Genet 170:1826–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anazi S, Maddirevula S, Faqeih E et al. (2017) Clinical genomics expands the morbid genome of intellectual disability and offers a high diagnostic yield. Mol Psychiatry 22:615–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglietto MG, Caridi G, Gimelli G et al. (2014) RORB gene and 9q21.13 microdeletion: Report on a patient with epilepsy and mild intellectual disability. Eur J Med Genet 57:44–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker CE, de Diego Otero Y, Bontekoe C et al. (2000) Immunocytochemical and biochemical characterization of FMRP, FXR1P, FXR2P in the mouse. Exp Cell Res 258:162–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD (2016) Hereditary ataxia overview In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA et al. (ed) GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudry-Labis E, Demeer B, Le Caignec C et al. (2013) A novel microdeletion syndrome at 9q21.13 characterised by mental retardation, speech delay, epilepsy and characteristic facial features. Eur J Med Genet 56:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer K, Foroushani AK, Laird MR et al. (2013) InnateDB: systems biology of innate immunity and beyond—recent updates and continuing curation. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D1228–D1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunberg E, Jensen P, Isaksson A, Keeling LJ (2013) Brain gene expression differences are associated with abnormal tail biting behavior in pigs. Genes Brain Behav 12:275–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns R, Majczenko K, Xu J et al. (2014) Homozygous splice mutation in CWF19L1 in a Turkish family with recessive ataxia syndrome. Neurology 83:2175–2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charng WL, Karaca E, Coban Akdemir Z et al. (2016) Exome sequencing in mostly consanguineous Arab families with neurologic disease provides a high potential molecular diagnosis rate. BMC Med Genomics 9:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG (2009) ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res 37:W305–W311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BWM et al. (2012) Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med 367:1921–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del’Guidice T, Latapy C, Rampino A et al. (2015) FXR1P is a GSK3β substrate regulating mood and emotion processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E4610–E4619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato N, Jean YY, Maga AM et al. (2016) Mutations in CRADD result in reduced caspase-2-mediated neuronal apoptosis and cause megalencephaly with a rare lissencephaly variant. Am J Hum Genet 99:1117–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozak J, Piecuch M, Poleszak O et al. (2015) UPF0586 protein C9orf41 homolog is anserine-producing methyltransferase. J Biol Chem 290:17190–17205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret JK, Engels H, Cremer K et al. (2015) Microdeletions in 9q33.3-q34.11 in five patients with intellectual disability, microcephaly, and seizures of incomplete penetrance: is STXBP1 not the only causative gene? Mol Cytogenet 8:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers C, Kaufmann L, Seitz A et al. (2016) Exome sequencing reveals a novel CWF19L1 mutation associated with intellectual disability and cerebellar atrophy. Am J Med Genet A 170:1502–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewenczyk C, Leroux A, Roubergue A et al. (2008) Recessive hereditary methaemoglobinaemia, type II: delineation of the clinical spectrum. Brain 131:760–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Sullivan EV (2015) Thalamic structures and associated cognitive functions: Relations with age and aging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 54:29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron L, Davies A, Page KM et al. (2008) The stargazing-related protein gamma 7 interacts with the mRNA-binding protein heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2 and regulates the stability of specific mRNAs, including CaV2.2. J Neurosci 28:10604–10607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garshasbi M, Hadavi V, Habibi H et al. (2008) A defect in the TUSC3 gene is associated with autosomal recessive mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 82:1158–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garshasbi M, Kahrizi K, Hosseini M et al. (2011) A novel nonsense mutation in TUSC3 is responsible for non-syndromic autosomal recessive mental retardation in a consanguineous Iranian family. Am J Med Genet A 155A:1976–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson DF, Thorvaldsson T, Kong A, Gunnarsson G, Ingolfsdottir A (2005) Allegro version 2. Nat Genet 37:1015–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MA, Qiu R, Wu X et al. (2013) Dynamics of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and chromatin marks in mammalian neurogenesis. Cell Rep 3:291–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel T, Hacohen N, Shaag A et al. (2017) Homozygous null variant in CRADD, encoding an adaptor protein that mediates apoptosis, is associated with lissencephaly. Am J Med Genet A 173:2539–2544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harripaul R, Vasli N, Mikhailov A et al. (2017) Mapping autosomal recessive intellectual disability: combined microarray and exome sequencing identified 26 novel candidate genes in 192 consanguineous families. Mol Psychiatry 23:973–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylycz MJ, Lein ES, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL et al. (2012) An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human transcriptome. Nature 489:391–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Kahrizi K, Musante L et al. (2018) Genetics of intellectual disability in consanguineous families. Mol Psychiatry. https ://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-017-0012-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SI, Shpyleva S, Melnyk S, Pavliv O, Pogribny IP (2014) Elevated 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the Engrailed-2 (EN-2) promoter is associated with increased gene expression and decreased MeCP2 binding in autism cerebellum. Transl Psychiatry 4:e460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Lv X, Lei X, Yang Y, Yang X, Jiao J (2016) Immune regulator MCPIP1 modulates TET expression during early neocortical development. Stem Cell Rep 7:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SG, Zhang ZM, Dunwell TL et al. (2016) Tet3 reads 5-carboxylcyto-sine through its CXXC domain and is a potential guardian against neurodegeneration. Cell Rep 14:493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen A, Rosti RO, Musaey D et al. (2016) Mutations in MBOAT7, encoding lysophosphatidylinositol acyltransferase I, lead to intellectual disability accompanied by epilepsy and autistic features. Am J Hum Genet 99:912–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS et al. (2007) Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai– Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat Genet 39:957–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa O, Al-Sahlawi Z, Imtiaz F et al. (2015) Variable expression pattern in Donnai–Barrow syndrome: report of two novel LRP2 mutations and review of the literature. Eur J Med Genet 58:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Rafiq MA, Noor A et al. (2011) A novel deletion mutation in the TUSC3 gene in a consanguineous Pakistani family with autosomal recessive nonsyndromic intellectual disability. BMC Med Genet 12:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J (2014) A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 46:310–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochinke K, Zweier C, Nijhof B et al. (2016) Systematic phenomics analysis deconvolutes genes mutated in intellectual disability into biologically coherent modules. Am J Hum Genet 98:149–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousar R, Nawaz H, Khurshid M et al. (2010) Mutation analysis of the ASPM gene in 18 Pakistani families with autosomal recessive primary microcephaly. J Child Neurol 25:715–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlenbäumer G, Young P, Oberwittler C et al. (2002) Giant axonal neuropathy (GAN): case report and two novel mutations in the gigaxonin gene. Neurology 58:1273–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Gudjonsson GH, Raghuvanshi S et al. (2013) Reduced thalamic volume in men with antisocial personality disorder or schizophrenia and a history of serious violence and childhood abuse. Eur Psychiatry 28:225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wei W, Zhao QY et al. (2014) Neocortical Tet3-mediated accumulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine promotes rapid behavioral adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:7120–7125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Yang D, Li J, Tang Y, Yang J, Le W (2015) Critical role of Tet3 in neural progenitor cell maintenance and terminal differentiation. Mol Neurobiol 51:142–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lise S, Clarkson Y, Perkins E et al. (2012) Recessive mutations in SPTBN2 implicate β-III spectrin in both cognitive and motor development. PLoS Genet 8:e1003074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wu C, Li C, Boerwinkle E (2016) dbNSFP v3.0: a one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum Mutat 37:235–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loddo S, Parisi V, Doccini V et al. (2013) Homozygous deletion in TUSC3 causing syndromic intellectual disability: a new patient. Am J Med Genet A 161A:2084–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv X, Jiang H, Liu Y, Lei X, Jiao J (2014) MicroRNA-15b promotes neurogenesis and inhibits neural progenitor proliferation by directly repressing TET3 during early neocortical development. EMBO Rep 15:1305–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matise TC, Chen F, Chen W et al. (2007) A second-generation combined linkage physical map of the human genome. Genome Res 17:1783–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E et al. (2010) The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20:1297–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megahed H, Nicouleau M, Barcia G et al. (2016) Utility of whole exome sequencing for the early diagnosis of pediatric-onset cerebellar atrophy associated with developmental delay in an inbred population. Orphanet J Rare Dis 11:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mientjes EJ, Willemsen R, Kirkpatrick LL et al. (2004) FXR1 knockout mice show a striated muscle phenotype: implications for Fxr1p function in vivo. Hum Mol Genet 13:1291–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JA, Ding SL, Sunkin SM et al. (2014) Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain. Nature 508:199–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir A, Kaufman L, Noor A et al. (2009) Identification of mutations in TRAPPC9, which encodes the NIK- and IKK-beta-binding protein, in nonsyndromic autosomal-recessive mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 85:909–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida GH, Mahajnah M, Hill AD et al. (2009) A truncating mutation of TRAPPC9 is associated with autosomal-recessive intellectual disability and postnatal microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet 85:897–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monies D, Abouelhoda M, AlSayed M et al. (2017) The landscape of genetic diseases in Saudi Arabia based on the first 1000 diagnostic panels and exomes. Hum Genet 136:921–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss FJ, Viard P, Davies A et al. (2002) The novel product of a fiveexon stargazing-related gene abolishes Cav2.2 calcium channel expression. EMBO J 21:1514–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M et al. (2011) Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature 478:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri I, Virdi A, Tortora G, Baldassari S, Seri M, Patrizi A (2016) Novel p.Glu519Gln missense mutation in ST14 in a patient with ichthyosis, follicular atrophoderma and hypotrichosis and review of the literature. J Dermatol Sci 81:63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SB, Turner EH, Robertson PD et al. (2009) Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature 461:272–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ et al. (2010) Exome sequencing identified MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat Genet 42:790–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Boesten I, Hellebrekers DM et al. (2016) Pathogenic CWF19L1 variants as a novel cause of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia and atrophy. Eur J Hum Genet 24:619–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novarino G, El-Fishawy P, Kayserili H et al. (2012) Mutations in BCKD-kinase lead to a potentially treaTable form of autism with epilepsy. Science 338:394–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak BJ, Deriziotis P, Lee C et al. (2011) Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat Genet 43:585–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SM, Hagen J, Muniz VP et al. (2014) NIAM-deficient mice are predisposed to the development of proliferative lesions including B-cell lymphomas. PLoS One 9:e112126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman AU, Santos-Cortez RLP, Drummond MC et al. (2015) Challenges and solutions for gene identification in the presence of familial locus heterogeneity. Eur J Hum Genet 23:1207–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter MS, Tawamie H, Buchert R et al. (2017) Diagnostic yield and novel candidate genes by exome sequencing in 152 consanguineous families with neurodevelopmental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 74:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazuddin S, Hussain M, Razzaq A et al. (2017) Exome sequencing of Pakistani consanguineous families identifies 30 novel candidate genes for recessive intellectual disability. Mol Psychiatry 22:1604–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S et al. (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17:405–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riess S, Reddihough DS, Howell KB et al. (2013) ALG3-CDG (CDG-Id): clinical, biochemical and molecular findings in two siblings. Mol Genet Metab 110:170–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rump P, Jazayeri O, van Dijk-Bos KK et al. (2016) Whole-exome sequencing is a powerful approach for establishing the etiological diagnosis in patients with intellectual disability and micro-cephaly. BMC Med Genomics 9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajid Hussain M, Marriam Bakhtiar S, Farooq M et al. (2013) Genetic heterogeneity in Pakistani microcephaly families. Clin Genet 83:446–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomons GS, Jakobs C, Pope LL et al. (2007) Clinical, enzymatic and molecular characterization of nine new patients with malonyl-coenzyme A decarboxylase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis 30:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnekenberg RP, Perkins EM, Miller JW et al. (2015) De novo point mutations in patients diagnosed with ataxic cerebral palsy. Brain 138:1817–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott EM, Halees A, Itan Y et al. (2016) Characterization of Greater Middle Eastern genetic variation for enhanced disease gene discovery. Nat Genet 48:1071–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelow D, Schuelke M, Hildebrandt F, Nürnberg P (2009) HomozygosityMapper—an interactive approach to homozygosity mapping. Nucleic Acids Res 37:W593–W599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Gilmore EC, Marshall CA et al. (2010) Mutations in the PNKP cause microcephaly, seizures and defects in DNA repair. Nat Genet 42:245–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks SE, Krasnewich DM (2017) Congenital disorders of N-linked glycosylation and multiple pathway overview In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA et al. (ed) GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Cohen JS, Vernon H et al. (2014) Clinical whole exome sequencing in child neurology practice. Ann Neurol 76:473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniak B, Kästner A, Poggi G et al. (2015) Accumulated common variants in the broader fragile X gene family modulate autistic phenotypes. EMBO Mol Med 7:1565–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamanini F, Willemsen R, van Unen L et al. (1997) Differential expression of FMR1, FXR1 and FXR2 proteins in human brain and testis. Hum Mol Genet 6:1315–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarailo-Graovac M, Shyr C, Ross CJ et al. (2016) Exome sequencing and the management of neurometabolic disorders. N Engl J Med 374:2246–2255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazir M, Nouioua S, Magy L et al. (2009) Phenotypic variability in giant axonal neuropathy. Neuromuscul Disord 19:270–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The GTEx Consortium (2013) The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 45:580–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenon J, Duffourd Y, Masurel-Paulet A et al. (2016) Diagnostic odyssey in severe neurodevelopmental disorders: towards clinical whole-exome sequencing as a first-line diagnostic test. Clin Genet 89:700–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins VS, Hagen J, Frazier AA et al. (2007) A novel nuclear inter-actor of ARF and MDM2 (NIAM) that maintains chromosomal instability. J Biol Chem 282:1322–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bokhoven H (2011) Genetic and epigenetic networks in intellectual disabilities. Annu Rev Genet 45:81–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasli N, Ahmed I, Mittal K et al. (2016) Identification of a homozygous missense mutation in LRP2 and a hemizygous missense mutation in TSPYL2 in a family with mild intellectual disability. Psychiatr Genet 26:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H (2010) ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 38:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Khan A, Han S, Zhang X (2017) Molecular analysis of 23 Pakistani families with autosomal recessive primary micro-cephaly using targeted next-generation sequencing. J Hum Genet 62:299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Benner MJ, Hancock RE (2014) NetworkAnalyst—integrative approaches for protein-protein interaction network analysis and visual exploration. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W167–W174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XL, Zong R, Li Z et al. (2011) FXR1P but not FMRP regulates the levels of mammalian brain-specific microRNA-9 and micro-RNA-124. J Neurosci 31:13705–13709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavarna T, Al-Dewik N, Al-Mureikhi M et al. (2015) High diagnostic yield of clinical exome sequencing in Middle Eastern patients with Mendelian disorders. Hum Genet 134:967–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YG, Zhao H, Miao L, Wang L, Sun F, Zhang H (2012) The p53-induced gene Ei24 is an essential component of the basal autophagy pathway. J Biol Chem 287:42053–42062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Dai J, Ma Y et al. (2014) Dynamics of ten-eleven translocation hydroxylase family proteins and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in oligodendrocyte differentiation. Glia 62:914–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]