Abstract

Background:

The need for effective and accepted method for opioid detoxification is ever increasing. Sublingual buprenorphine and oral clonidine have been effective in opioid detoxification. As often, there is a great variation in the dosage of buprenorphine and clonidine prescribed by the clinicians; hence, there is a felt need to find an effective dosage for a favorable outcome of opioid detoxification.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of different doses of sublingual buprenorphine and clonidine in opioid detoxification.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 100 patients with the diagnosis of opioid dependence as per the international classification of diseases-10 criteria were recruited for this study. Participants were assigned randomly into four groups – low-dose clonidine, high-dose clonidine, low-dose sublingual buprenorphine, and high sublingual dose buprenorphine using a computer-generated random number table, resulting in 25, 26, 23, and 26 patients in each group, respectively.

Results:

The four groups had comparable scores on all the items of “stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale” for the assessment of motivation at baseline. Progressive decrease in withdrawal score was seen in all the groups on “clinical opiate withdrawal scale” and “subjective opiate withdrawal scale.”

Conclusion:

From the current study, we can infer that both low and high doses of buprenorphine and clonidine are comparable regarding controlling withdrawal.

Key words: Buprenorphine, clonidine, detoxification, opioid

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, globally, it was estimated that between 162 million and 324 million people, corresponding between 3.5% and 7.0% of the world population aged 15–64 years, had used an illicit drug at least once in the previous year.[1] Of these drugs of abuse, opioid dependence continues to be a serious public health issue in many parts of the world. Moreover, among opioid users, approximately half uses heroin whereas the other half uses opium or diverted pharmaceutical opioids.[2] Approximately 12.7 million people which correspond to a prevalence of 0.27% (range: 0.19%–0.48%) of the population aged 15–64 years inject opioids. Out of all the treatment seekers for substance use, the opioid is the most common primary drug of abuse in Asia and Europe. In India, the national household survey on the prevalence of drug use has reported that the prevalence of opioid use is about 0.7%[3] and many studies point to a prevalence of 0.4%–2%.[4]

The range of treatment interventions for opioid uses includes voluntary programs such as detoxification, abstinence-oriented treatments, buprenorphine, and oral methadone maintenance treatment, as well as involuntary options imposed by the criminal justice system.

Detoxification is a supervised withdrawal from a drug of dependence that attempts to minimize withdrawal symptoms, and it is prelude to abstinence-based treatment.[5] In case of opioid detoxification, different methods have been tried, but none has been proven to be perfect.[3,6,7] Clonidine which is a α2-adrenergic receptor agonist and imidazoline receptor agonist has been in clinical use for over 40 years.[8] Clonidine also demonstrates anticraving effect for opioids.[9] A new technique in opiate detoxification with clonidine called “house detoxification” was developed in Israel.[10] However, clonidine can cause serious side effects such as sedation and hypotension, rebound hypertension, atrioventricular block, and bradycardia. These side effects restrict its use in the outpatient setting.[11] Buprenorphine, a partial μ-opioid agonist and κ-opioid antagonist with a long half-life, has less abuse potential than methadone and has been shown to be equivalent in efficacy with clonidine.[12,13]

Buprenorphine is often prescribed in very high doses (16–32 mg/day) in several Western studies.[14,15] On the other hand, clinicians and researchers from India have shown its effectiveness in lower doses.[16,17] Some of the recent studies from India have used buprenorphine in very wide dose ranging from 2 to 14 mg/day for maintenance treatment.[18,19] However, in the absence of clear guidelines regarding the dosage in opioid detoxification and substitution, the chances of overdosage or inadequate dosage are very high which may then lead to untoward incidents.

Keeping in view, the challenges faced in opioid detoxification, the current study was envisioned to compare clonidine in low and high doses with buprenorphine in low and high doses for opioid detoxification in an inpatient setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population

Patients were enrolled from the Department of Psychiatry at a tertiary care teaching hospital, Chandigarh, India.

Sample

A total of 100 patients with the diagnosis of opioid dependence as per the International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria, fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited for the study.[20] Participants were randomly assigned into four groups – low-dose clonidine (CL), high-dose clonidine (CH), low-dose buprenorphine (BL), and high-dose buprenorphine (BH) using a computer-generated random number table, resulting in 25, 26, 23, and 26 patients in each group, respectively.

Inclusion criteria

(a) Participants who gave consent and were willing to get admitted for the study; (b) male participants in the range of age 18–60 years who were willing to give urine sample for opioid screening on demand; and (c) in case of comorbid mental illness, those patients who were clinically stable were included in the study (for the purpose of the study, these were those cases where there have been no change in medication or increase in dose by 50% in the past 3 months).

Exclusion criteria

(a) The presence of comorbid medical/surgical illness in which clonidine and buprenorphine use was contraindicated (assessed through physical examination, past history, and routine laboratory screening); (b) presence of another coexisting substance dependence disorder except that of nicotine and caffeine; (c) presence of evidence of being intellectually challenged or having active major mental disorder causing cognitive decline; (d) participants on opioid maintenance treatment; (e) participants reporting after 48 h of last use of opioid; (f) actively suicidal patient; and (g) history of any adverse drug reaction with buprenorphine and clonidine in the past.

Design

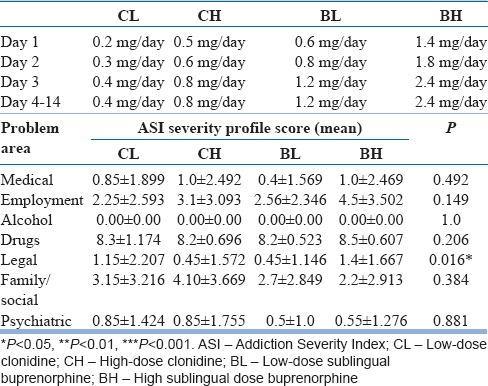

It was a comparative, open-label, and prospective study conducted at the Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh, India. After obtaining informed consent, participants fulfilling the selection criteria were admitted in the psychiatry ward for detoxification. The participants were randomly assigned to CL, CH, BL, or BH group using random table number. At the time of admission, it was predecided to complete detoxification within 14 days. On day of admission, each patient was screened for urinary opioid by the principal investigator before starting the detoxification to confirm the active use of opioid. The CL and the CH groups were kept on 0.2–0.4 and 0.5–0.8 mg/day of oral clonidine, respectively. The BL BH groups were kept on 0.6–1.2 and 1.4–2.4 mg/day of sublingual buprenorphine, respectively. It is pertinent to mention here that before carrying out this study, we had a look at the case records of patients in the previous year who were receiving clonidine or buprenorphine for opioid detoxification. These low and high doses of clonidine and buprenorphine were thus based on our clinical experience in the deaddiction ward where we had seen response to treatment in both these regimens (low and high). Moreover, this randomization to a high- and low-dose group of clonidine and buprenorphine was also based on the consensus of all the psychiatrists in the department and agreed on by the research committee of the institute. The medicines in all the four groups were started from lower dose, and maximum dose was reached on 3rd day of detoxification, and the patients were kept on the same dose for the rest of the study period. For ensuring compliance, the medicines were dispensed by the principal investigator. Table 1 shows the design of dosing schedule of two drugs for four groups and severity of dependence on addiction severity index (ASI).

Table 1.

Design of dosing schedule of clonidine and buprenorphine and addiction severity index score

Ancillary medicines, such as lorazepam for sleep, diclofenac for pain, and oral rehydration solution (ORS) for dehydration, were allowed during the study period. All the four groups received nonpharmacological intervention which was as per the standard protocol followed in the Department for Substance Dependence. To ensure abstinence, surprise checking was carried out by the security staff, and random urine screening was done for any illicit opioid (other than buprenorphine) from time to time. The urine screening was carried out using cassettes (kits) which can detect opioid or its metabolite in urine.

Patients, who developed severe adverse drug reaction to clonidine or buprenorphine, were dropped from the study and were managed as per the standard treatment protocol in the department. If during ward stay, any patient was found to be tested positive on urine screening for opioid (other than buprenorphine), he was dropped from the study. Although the study was over at the end of 14th day, the patient continued to receive treatment and care from the treating team wherever required.

At the time of induction in the study, the participants were assessed for substance-related clinical variables (duration and dose of opioid use, health hazards related to opioid consumption, past treatment attempts, and quantity of substance use, whether it was natural, semisynthetic, or synthetic) and sociodemographic data (age, socioeconomic status, marital status, level of education, occupation, and residence) on semi-structured pro forma. The modified Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale was used for the assessment of socioeconomic status.[21] Even though the patient was the primary source of information related to opioid use, a family member or a close relative was also interviewed to corroborate the information provided by the patient.

Participants in all the four groups were assessed for the severity of opioid dependence on “addiction severity index (ASI)”-5th edition[22] at baseline. Participant's motivation at baseline and at time of completion of the study was assessed on “stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES 8D).”[23] The severity of withdrawal symptoms was evaluated with “clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS)”[24] and “subjective opiate withdrawal scale (SOWS)”[25] for opioid.

The withdrawal scores were assessed at baseline and every 24 h in the morning at fixed time during the period of detoxification. Patients were also asked to rate the average score of craving for each day on “visual analog scale (VAS).”[26] Adverse effects related to medicines (clonidine and buprenorphine) in all the four groups were measured every day by administering a symptom checklist. Other investigations, such as complete hemogram, liver function test, and electrocardiography, were done to identify comorbid medical conditions.

On day 1, before starting clonidine or buprenorphine, opioid urine screening was carried out to ascertain the active opiate use, and later, it was followed up with random screening for illicit opiate use (other than buprenorphine) during the treatment. Urine screening for opiate was done using qualitative immunoassay. The test was standardized to detect small quantity of opiates in the urine (morphine/opiates, 300 ng/ml; propoxyphene, 300 ng/ml; oxycodone, 100 ng/ml; buprenorphine, 10 ng/ml; and tramadol, 200 ng/ml).

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and the guidelines of Central Ethics Committee for biomedical research on human participants by the Indian Council of medical research were adhered to, in addition to the principles enunciated in the “Declaration of Helsinki.”[27]

Statistical analysis

Pearson Chi-square test was used to compare the demographic profile and variable related to opioid (nominal data) in all the four groups. ANOVA was used to compare ordinal data within all groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the four groups together, and the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare individual group with other groups.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare pre- and post-test values of motivation. Frequency tables were generated for side effects assessment. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package for Windows (Version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago). Analyzed data are represented in numbers, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The level of statistical significance was kept at P < 0.05.

This study was registered with the Clinical Trial Registry – India No. CTRI/2016/03/006766.

RESULTS

This study included 100 patients who were divided into four groups, i.e., CL, CH, BL, and BH on the basis of computer-generated random numbers, and there were 25, 26, 23, and 26 patients in CL, CH, BL, and BH, respectively. During the study, 20 patients dropped out (five from CL, six from CH, three patients from BL, and six patients were from BH) and majority of the patients cited more than one reason for dropping out. However, they had the option to receive treatment as usual despite dropping out from the study. Reasons for dropout are shown in Table 2. The remaining 80 patients completed the 14-day detoxification period in the ward.

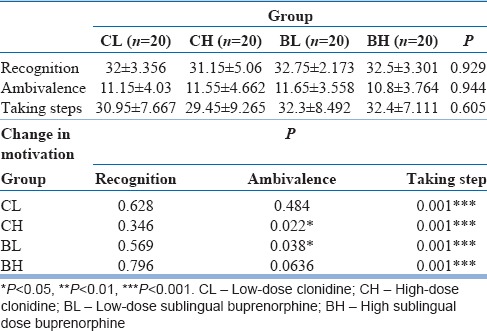

Table 2.

Comparison of Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES8D) score at admission (values in mean±standard deviation) and change in motivation at discharge

Of these 20 dropout cases, 14 patients (14/20, 70%) dropped out during the first 4 days of study.

Sociodemographic profile of the patients

All the four groups had comparable sociodemographic profile and did not have any statistically significant difference among them except in the area of occupation which was found to be statistically significant. The mean age of the sample was 29.36 years and more than 56% of the total participants were educated until secondary level or above. About 47.3% were married and almost equal numbers (48.8%) were never married. A total of 25% of participants were unemployed on long term, and 75% were employed. Majority of the participants belonged to the Sikh religion (60%) were living in nuclear families (46.3%) and most (51.3%) belonged to the upper middle socioeconomic status.

Comparison of opioid used by participants

Patients in all the four groups were comparable on the pattern of opiate abuse including the type of opioid usage (opium, heroin, semisynthetic opiate, and injectable opiate use).

About 70% of the patients had a history of treatment for substance use disorders in each group. Around 65% of the patients had concomitant nicotine dependence in all the four groups.

Addiction severity index severity profile

Table 1 shows the mean severity scores measured on ASI in various areas. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used. A significant difference was found in the “legal problem, area” in comparing all the four groups together.

Comparison of Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale score at admission and at discharge

The four groups had comparable scores on all the items of SOCRATES 8D for the assessment of motivation at baseline/admission and change in motivation in each group is shown in Table 2. Significant changes were noted in “ambivalence” item in CH and BL groups, and highly significant changes were noted in “taking step” item in all four groups.

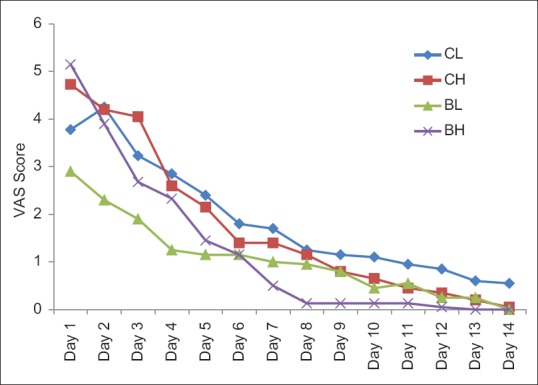

Comparison of craving among the groups

All the four groups had comparable total VAS score. There was a progressive reduction in craving in all the groups. Craving was least in BL group during initial 5 days, thereafter gradual reduction in craving in BH group over, rest of the study period was reported; however, it was not statistically significant as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The comparison of mean of visual analog scale score between the four groups during the study period

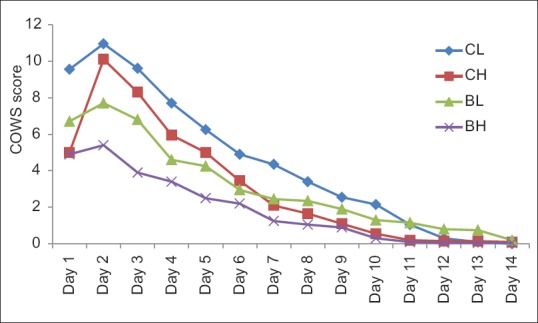

Comparison of objective withdrawal symptoms during detoxification

Figure 2 shows the total COWS score in four groups during the detoxification phase. Progressive reduction in withdrawal score was seen in all the groups. The mean scores did not reach zero even on day 14, except in CL group. Withdrawal score was maximum in CL group and least in BH group. Statistically significant changes were noted from day 2 to day 7 on comparing the four groups, with least withdrawal score in BH group and maximum withdrawal score in CL group. However, the difference in withdrawal score was not statistically significant from day 8 onward.

Figure 2.

Total clinical opiate withdrawal scale score of four groups during detoxification

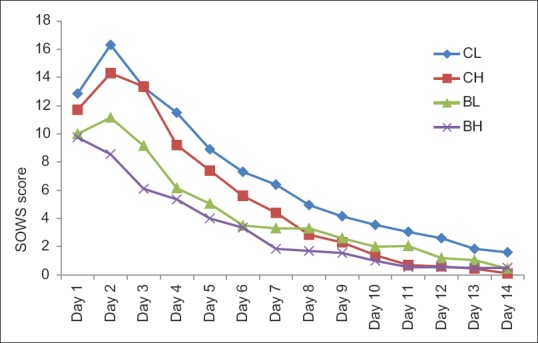

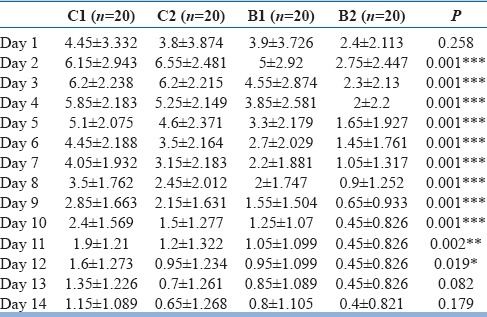

Comparison of subjective withdrawal symptoms during detoxification

Figure 3 shows the total SOWS scores in four groups during the detoxification phase. Although the mean score did not reach zero even on day 14 in any group, there was a progressive decrease in withdrawal score in all the four groups. Withdrawals were seen to be maximum in CL group and least in BH group as seen in COWS. Statistically significant changes were noted from day 2 to day 4 on comparing the four groups, with least withdrawal seen in BH group and maximum withdrawal in CL group.

Figure 3.

Total subjective opiate withdrawal scale score of four groups during detoxification

Comparison of ancillary medicine used

Ancillary medicine includes lorazepam for insomnia and anxiety, ORS for dehydration and diclofenac was used only in the clonidine groups (CL and CH) for controlling pain. In the CL and CH groups, diclofenac wherever required was not used beyond 7 days, and there was no significant difference between these two groups.

Table 3 shows the average dose (in milligrams) of lorazepam used in the study period in all the four groups. The patients in the clonidine group, both low and high doses, received higher dose of lorazepam then buprenorphine, and it was statistically significant. There was a decrease need of lorazepam dose over the study period in all the four groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of dose of lorazepam used (values in mean±standard deviation)

Comparison of adverse effects

Adverse effects of the drugs were recorded during the study. Majority of the patients (62.5%) experienced adverse effect. Maximum numbers of patients in CH and BH groups (high-dose group) experienced adverse effects. However, none of the patients required either dose reduction or discontinuation of medication due to these adverse effects.

Although clonidine-induced hypotension (blood pressure fall <90/60 mmHg) did not occur in any patient, there was a decrease in blood pressure from baseline in four and seven patients of CL and CH groups, respectively. Similarly, although bradycardia (heart rate <60 beats/min) was not noted in any patient, there was a decrease in heart rate from baseline in three patients of CH group. Transient sadness was reported by one patient of CL and two patients of CH groups. Transient sleep disturbances in the form of delay in onset were also reported. Dry mouth was the most common side effect reported by both the groups; however, it was more in CH group.

Miosis was most commonly seen in buprenorphine group, but it was not troublesome for the patients. Many of the side effects overlapped with the withdrawal symptoms. Diarrhea, chills, nausea, and vomiting persisted for initial few days only.

DISCUSSION

The present study is somewhat unique in the sense that it makes an attempt to compare buprenorphine, an opioid partial agonist with that of clonidine which is a nonopioid drug and see their effectiveness in control of withdrawal symptoms due to opioid dependence. Although studies are there that have looked at the effectiveness of nonopioid drugs such as clonidine, venlafaxine, buspirone, quetiapine, etc., on as well as the several opioid agonists/partial agonists,[28] there is almost no study in India which compares these two distinct and different category of drugs. The study further compares both these drugs at two different dosage regimens (one at a lower dosage and the other at a comparatively higher dosage) to see their effectiveness in controlling withdrawals due to the opioid intake. To the best of the knowledge of the authors, such a novel strategy has never been employed elsewhere in India.

The findings of the present study showed that large numbers of opioid users in India have shifted to synthetic and semisynthetic forms of opioid as 73.75% of patients in our study were using heroin, dextropropoxyphene, and diphenoxylate and only 13.8% used crude form of opioid (opium). This paradigm shift of usage from natural and locally available crude forms of opioid (opium) to the synthetic and semi-synthetic forms has been reported from another hospital-based study as well.[29] This is a major cause of concern for the clinicians, policymakers, and the society, as this is causing high dependence, increased legal problems, and health hazards. The mean age of the participants in our study was 21.12 years with a mean duration of use of 6.8 years which indicate early age of onset, a finding which is similar to an earlier study.[17]

In the present study, the average motivation scores on SOCRATES scale in the area of taking steps' were higher at the end of the study in participants as compared to that during admission in all the four groups. Mean scores at admission were between low and medium level of motivation, and at discharge, they were in very high or high level. However, it is worthy to mention here that significant changes were noted in “ambivalence” in CH and BL groups. This change in “ambivalence” is difficult to comprehend. It is possible that there could be certain intrinsic factors (which may not have been analyzed such as genetic predisposition and personality factors.) in these groups whose interplay could have resulted in such differences. No previous study has commented on motivation in the past while comparing the use of clonidine and buprenorphine. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no study has reported the effect of detoxification on “motivation” in opioid users.

In the present study, there was a progressive decrease in craving in all the four groups during the study. This finding is similar to some of the earlier studies that compared reduction in craving between these two drugs.[16,30,31] It is also pertinent to mention here that, no statistically significant difference was observed between two drugs, even when 8–16 mg of buprenorphine per day[16] and parenteral routes[13,32] were used, against oral clonidine up to 0.6 mg/day and clonidine in patch form.

Conventionally, Indian psychiatrists have been using very low doses of buprenorphine, both for detoxification as well as for substitution therapy[17] though dosage as high as 4–8 mg per day and even higher has also been used.[18,19] The findings of the present study showed that patients in high-dose buprenorphine group had better control of withdrawal symptoms, and the difference was significant when compared with low-dose buprenorphine. Furthermore, the dose of lorazepam was much less in patients who were receiving high dose of buprenorphine without increasing the risk of adverse effects. This need for lower doses of ancillary medicines is noteworthy, as a study has pointed out that the use of such medicines with buprenorphine does not improve the outcome in the context of treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms during detoxification.[33] In fact, low dose of buprenorphine was found to be inferior even when compared with low dose of clonidine in the present study.

In the present study, although the high dose of buprenorphine was more effective, the low dose of buprenorphine and clonidine is low and high doses were also effective in controlling the withdrawal symptoms. Maximum mean withdrawal scores were within the mild category[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] of COWS in all the four groups. It shows that drugs in all the groups were very effective in controlling withdrawal, a finding which is further strengthened by that of earlier studies which have defined suppression of withdrawal as achieving a COWS score of less than 12.[30,34] Surprisingly, the mean withdrawal scores did not reach zero even toward the end of the study in all the four groups. Similar finding has been depicted by an Indian study wherein mean withdrawal score persisted above zero even at the end of the study on day 11.[17] This finding holds significance as the persistence of withdrawal symptoms can lead to early relapse and poor motivation for nonpharmacological intervention for relapse prevention.[35] In such a scenario, long-term maintenance treatment should be carefully planned to prevent relapse.

The present study shows that clonidine in low doses (CL) is as effective as high dose (CH) as indicated by COWS and SOWS scores. In fact, more patients in high-dose clonidine group reported high craving and unacceptable withdrawal. The reason for these needs to be explored, and further study may throw some light in this regard. However, from the current study, one can justify the unnecessary avoidance of higher doses of clonidine for effective control of withdrawal symptoms due to opioid use. Previous studies have used clonidine up to 1.2 mg/day[30] for effective detoxification; however, there is no study comparing different doses of clonidine.

In the present study, there has been 20% dropout (data not shown) and it is almost equal in all the four groups. About 70% of patients dropped out during the initial 4 days. An Indian study reported 36.2% dropout rate which was maximum on day 5.[17] Western studies show very high variation in dropout ranging from 11% to 40%. In these studies, the clonidine group had more dropouts.[16,18] In some of the studies, dropouts were almost double or more in clonidine group than buprenorphine group.[16,32]

In the present study, dropouts (data not shown) due to fall in blood pressure were similar in patients receiving high and low dose of clonidine. However, unlike the earlier studies,[12,17,35] none of the patients in our study had to be dropped due to hypotension or required withholding of clonidine dose because of fall in blood pressure. Dryness of mouth was the most common side effect reported in the clonidine group and was dose related, as it was almost three times more in the high-dose group. A previous Indian study using 0.9 mg clonidine had reported a high rate of side effects (up to 80%), and giddiness was the most common side effect.[17] No dropout was seen in the buprenorphine group because of side effects. An earlier study had reported a lower respiratory rate and higher sedation in the buprenorphine group during the 3 days of treatment.[12]

The present study addresses several issues in addition to the effectiveness of the various doses of clonidine and buprenorphine in control of withdrawal due to the opioid use such as assessing withdrawal in a subjective as well as objective manner, assessing motivation and craving, looking at the reasons for dropout, and measuring the severity of addiction in a structured manner. Moreover, the present study had a robust design with homogenous sample who were strictly monitored in an inpatient setting with surprise urine sample check for the presence of opioids apart from buprenorphine. Further studies may be planned in a similar fashion with bigger sample size, blinding the investigators, introducing a placebo arm as well, and using advanced investigations such as urine chromatography for detecting opioid to complement or contradict the finding of the present study.

Thus, from the present study, we can conclude that both low and high doses of buprenorphine and clonidine were comparable regarding controlling withdrawal. However, buprenorphine in higher doses (2.4 mg/day dose) has been found to be superior in controlling withdrawal symptoms with less need for ancillary medicines, when compared with the other three groups.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations Office on Drug and Crime. Vienna: World Drug Report. 2013. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/secured/wdr/wdr2013/World_Drug_Report_2013.pdf .

- 2.Murthy P, Manjunatha N, Subodh BN, Chand PK, Benegal V. Substance use and addiction research in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S189–99. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Baxter AJ, Charlson FJ, Hall WD, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1564–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saddichha S, Manjunatha N, Khess CR. Clinical course of development of alcohol and opioid dependence: What are the implications in prevention? Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:359–61. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattick RP, Hall W. Are detoxification programmes effective? Lancet. 1996;347:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosten TR. Current pharmacotherapies for opioid dependence. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stine SM, Kosten TR. Use of drug combinations in treatment of opioid withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora A, Williams K. Problem based review: The patient taking methadone. Acute Med. 2013;12:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neil MJ. Clonidine: Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use in pain management. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6:280–7. doi: 10.2174/157488411798375886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telias D, Nir J. Buprenorphine-ketorolac vs. clonidine-naproxen in the withdrawal from opioids. Int J Psychosocial Rehabil. 2000;5:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gossop M. Clonidine and the treatment of the opiate withdrawal syndrome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1988;21:253–9. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(88)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheskin LJ, Fudala PJ, Johnson RE. A controlled comparison of buprenorphine and clonidine for acute detoxification from opioids. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36:115–21. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janiri L, Mannelli P, Persico AM, Serretti A, Tempesta E. Opiate detoxification of methadone maintenance patients using lefetamine, clonidine and buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36:139–45. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowing LR, Farrell M, Ali RL, White JM. Alpha2-adrenergic agonists in opioid withdrawal. Addiction. 2002;97:49–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce RD, Altice FL. Clinical care of the HIV-infected drug user. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:149–79, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling W, Amass L, Shoptaw S, Annon JJ, Hillhouse M, Babcock D, et al. Amulti-center randomized trial of buprenorphine-naloxone versus clonidine for opioid detoxification: Findings from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Addiction. 2005;100:1090–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nigam AK, Ray R, Tripathi BM. Buprenorphine in opiate withdrawal: A comparison with clonidine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1993;10:391–4. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90024-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lintzeris N, Bell J, Bammer G, Jolley DJ, Rushworth L. A randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine in the management of short-term ambulatory heroin withdrawal. Addiction. 2002;97:1395–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Operational Guidelines for the Management of Opioid Dependence in the South-East Asia Region. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Description and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bairwa M, Rajput M, Sachdeva S. Modified Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic scale: Social researcher should include updated income criteria, 2012. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:185–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.116358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 04-3939. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [Last accessed on 2018 Jul 30]. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64245/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK64245.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS) J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253–9. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD, et al. Two new rating scales for opiate withdrawal. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13:293–308. doi: 10.3109/00952998709001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reips UD, Funke F. Interval-level measurement with visual analogue scales in internet-based research: VAS generator. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:699–704. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants. New Delhi: ICMR; 2006. Central Ethics Committee on Human Research. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar S, Mattoo SK. Newer approaches to opioid detoxification. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21:163–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.119652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu D, Aggarwal M, Das PP, Mattoo SK, Kulhara P, Varma VK, et al. Changing pattern of substance abuse in patients attending a de-addiction centre in North India (1978-2008) Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:830–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oreskovich MR, Saxon AJ, Ellis ML, Malte CA, Reoux JP, Knox PC, et al. Adouble-blind, double-dummy, randomized, prospective pilot study of the partial mu opiate agonist, buprenorphine, for acute detoxification from heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gossop M. Medically supervised withdrawal as stand-alone treatment. In: Strain EC, Stitzer ML, editors. The Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006. pp. 346–62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fingerhood MI, Thompson MR, Jasinski DR. A comparison of clonidine and buprenorphine in the outpatient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Subst Abus. 2001;22:193–9. doi: 10.1080/08897070109511459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillhouse M, Domier CP, Chim D, Ling W. Provision of ancillary medications during buprenorphine detoxification does not improve treatment outcomes. J Addict Dis. 2010;29:23–9. doi: 10.1080/10550880903438925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liebschutz JM, Mulvey KP, Samet JH. Victimization among substance-abusing women. Worse health outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1093–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regidor E, Barrio G, de la Fuente L, Rodríguez C. Non-fatal injuries and the use of psychoactive drugs among young adults in Spain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;40:249–59. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]