Abstract

Background:

Raising a child with intellectual disability (ID) can add to parenting stress significantly. This stress can manifest into psychopathologies such as anxiety and depression. The aims of the study were to assess psychopathology and coping mechanisms in parents of children with ID.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 100 consecutive consenting parents of children with ID were interviewed from child psychiatry outpatient department of a municipal-run tertiary care teaching hospital. A semi-structured pro forma, symptom checklist 90 revised (SCL90R) and Mechanism of Coping Scale (MOCS) were used for assessment.

Results:

Mean age for the parents was 37.02 (±7.35) years, and for the children, it was 8.29 (±3.11) years. There were 60 mothers and 61 parents of a male child among sample. Eighty-five of parents considered their child's ID to be a major concern in their life. Depression had highest mean among psychopathologies. Mothers had higher score for depression and Interpersonal-sensitivity. Parental psychopathology did not differ significantly with severity of ID of child. Global severity index of SCL90R correlated negatively with age of parents (P = 0.015) and positively with fatalism (P = 0.004), expressive-action (P < 0.000) and passivity (P = 0.001) coping mechanisms.

Conclusion:

Depression is the most common psychopathology especially among mothers of child with ID. Psychopathology is independent of severity of ID and worsens with coping mechanisms like fatalism, expressive-action, and escape-avoidance. A child with ID should be seen and treated as a family unit giving enough attention to parent's psychological needs as well.

Key words: Coping, intellectual disability, parents, psychopathology

INTRODUCTION

Child-birth is a major event, hugely affecting the family dynamics. It is associated with joy, dreams, aspirations, and hopes. However, parenting is a demanding job which gets more so in case the child is suffering from a disability, such as intellectual disability (ID).

The overall prevalence of ID is about 1% with rates in low-income group countries and child/adolescent being on higher side.[1] Data suggest the prevalence of 10.5 per 1000 in India with prevalence slightly higher in urban India than rural parts.[2] It is more common in developing countries due to higher incidence of injuries and anoxia or deprivation of oxygen at birth and early childhood brain infections. There are many causes of ID such as congenital infection, chromosomal abnormality, and deficiency syndrome, etc., but doctors find a specific reason in few cases in milder ID than in the severer forms.[3]

There are various medical and psychiatric comorbidities to add to the complexity of management of intellectually disabled.[4] The parents end up shuttling between psychiatrist, physicians, occupational therapist, and special educators. They end up investing most of their time and energy in the child's needs, leaving them with little time for themselves. Both parents may experience great stress as they adapt and learn to care for their special child.

There is an increasing parental burden in the form of interferences in the family routine, which result in social, marital familial, and emotional problems. Stress often appears to increase with the age of the afflicted child and is based on the daily caregiving demands of the child.[5] Other general factors affecting stress include parental locus of control, self-esteem, family support, social isolation,[6,7] as well as financial status of family.[5] Whereas, each parent has a unique style to cope with the situation they face. Emotion-based coping mechanism makes them prone to psychiatric illness, and use of problem-based coping mechanism may have a positive impact on the stress of the parent.[5]

Studies have shown significant psychological distress associated with parenting of children with ID.[8,9] Recent investigations from the Indian subcontinent suggest that the parents have a significant level of anxiety and depression when children are suffering from ID.[5,10,11] Although anxiety and depression has been studied by various authors, other areas of psychopathology have not been adequately explored. Further, the role of specific coping mechanisms and its relation to psychopathology has not yet been explored. This area is imperative to study as it will impact the overall management of these cases.

The current study is undertaken with the objective to promote better understanding of problems of parents of children with ID. The aims of the study were to assess psychopathology, coping mechanism, and factors such as age, gender as well as correlation in parents of child with ID.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

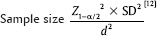

Design and sample size: This was a cross-sectional single interview study and participants were obtained from School Mental Health Clinic run by Department of psychiatry in tertiary care municipal teaching hospital, Mumbai, India. Sample selection was consecutive and 100 parents of children with ID were interviewed between October 2010 and September 2011. With a 95% confidence interval and 5% Type 1 error, the sample size (namely, the number of patients that need to be interviewed) was calculated using the following formula:

Where, Z1-α/2 =1.96 (standard normal variate at 5% type 1 error); SD = 0.32 (standard deviation for Global Severity Index [GSI] from previous study[13]); d = 0.1 (degree of precision assumed with respect to GSI score). The estimated sample size came to be around 40.

Ethics

The study protocol was presented to Institutional Ethics Committee and was approved before commencement of the study. The parents of children with ID who came for evaluation of their child to School Mental Health Clinic of psychiatry department were briefed about the study, assured confidentiality, and written informed consent was obtained before commencing the interview. Confidentiality was maintained using unique identifiers.

Selection criteria

Participants included were those between 18 and 60 years of age, willing and able to give the written informed consent. Participants who were already diagnosed with a psychiatric illness or suffering from a major disabling illness were excluded from the study. In addition, the parents whose another child was suffering from any chronic condition or psychiatric illness were excluded from the study. For each child, only one of the biological parents was interviewed.

Data collection

Parents enrolled for the study were given convenient appointment and called for interview. The investigator interviewed with the help of especially designed case record form for noting the sociodemographic details about the parents as well as child's age, IQ, etc. Further psychopathology was assessed using Symptom Check List 90 R and Mechanism of Coping Scale (MOCS) was used to assess the coping mechanisms in the event of stress. Each interview was completed in a single session and lasted for 45 min to 1 h.

Symptom checklist 90 revised (SCL90R):[14] It is a screening instrument for general psychopathology symptoms. It consists of 90 self-rated items responses of which are scored on 0–4 continuums. The SCL90R covers nine symptoms dimensions: somatization (Som), obsessive-compulsive (OC) symptoms, interpersonal-sensitivity (IPS), depression (Dep), anxiety (Anx), anger-hostility (Host), phobic-anxiety (Phob), paranoid ideation (Par), and psychoticism (Psy) along with a global severity index (GSI). GSI is mean score of all responses on SCL90R. The internal consistency coefficient alphas for the nine symptom dimensions ranged from 0.77 for psychoticism, to a high of 0.90 for depression. GSI score of >0.57 indicated a significant general distress.[15] The Global Assessment of Functioning (Axis V, DSM IV) is significantly related to concurrent GSI scores.[16] Anxiety and depression subscales have shown acceptable concurrent validity to anxiety and depression diagnoses[17] The scale was translated to Hindi and backtranslated for the purpose of study

Mechanism of Coping Scale (MOCS): MOCS by Parikh et al.[18] is modified Indian version of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire by Folkman and Lazarus.[19] Selected items of the original scale as well as six items of fatalism are included in this study. Divided into five individual ways of coping as escape-avoidance (Esc), fatalism (Fat), expressive-action (Exp), problem-solving (Prob), and passivity (Pass). The scores are calculated for each of these factors. The scores range from 0-not used at all to 3-used a great deal. The average score for each factor is calculated by dividing the total score by number of items comprising that factor to arrive at the mean factor score. MOCS is widely used and time-tested scale to assess the coping mechanism in a wide range of study subjects including parents.[20,21,22,23,24,25]

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS-20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The continuous variables are summarized as mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range). Further, Unpaired t-test is used for comparison between two groups and ANOVA for more than two groups. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used for correlating continuous variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We interviewed 100 parents out which 60 were mothers. Sixty-one of 100 parents had their son suffering from ID. Mean age for the parents was 37.02 (±7.35) years ranging from 22 to 55 years of age. Mean age of children was 8.29 (±3.11) years ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Forty-three of the parents were educated till primary level or less, 36 were educated till secondary and 21 went on to pursue at least bachelor's degree. Sixty-nine of the children were being raised in a nuclear family and the rest belonged to joint families. Forty-one of the children had mild, 28 had moderate, 18 had severe and 13 had profound ID. We asked the parent about their perception of their child's ID, 85 of them considered it to be a major concern and 15 regarded it as a minor concern in their life.

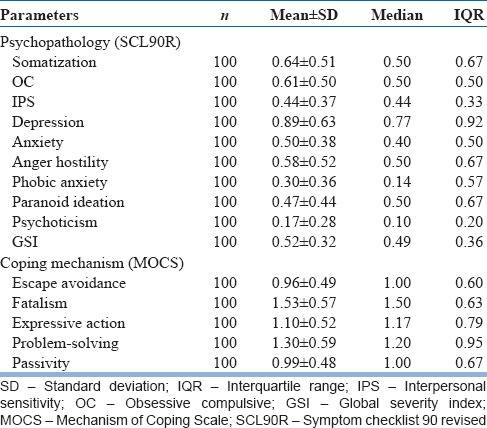

The highest mean psychopathology was for subscale of depression followed by somatization, obsessive-compulsive and anger-hostility subscales for the study sample [Table 1]. The Fatalism subscale of coping had highest mean for sample, problem-solving, and Expressive action were next highest means [Table 1].

Table 1.

Psychopathology and coping mechanisms variables in sample

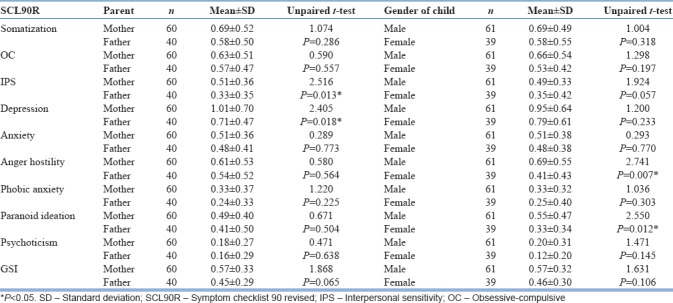

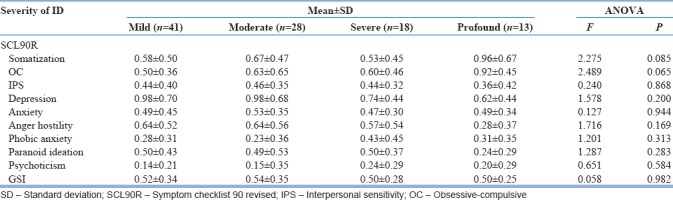

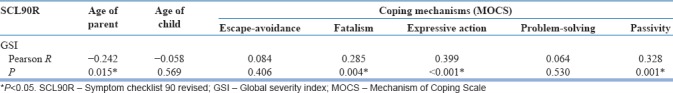

On analysis of the parents, we found a significant difference in both genders with relation to IPS and depression, on the subscales. Further, parents of male children scored significantly higher on anger-hostility and paranoid-ideation [Table 2]. Psychopathology did not differ significantly among the grades of ID [Table 3]. General symptom index of psychopathology had a significant negative correlation with age of parents and significant positive correlation with fatalism, expressive-action, and passivity coping mechanisms [Table 4].

Table 2.

Association between psychopathology and gender of parents, children

Table 3.

Association of psychopathology and severity grades of ID

Table 4.

Correlation of general symptom index of psychopathology with other variables

DISCUSSION

This study examined the psychopathology and coping of parents of children with ID. As a child with ID develops, there is increasing parental burden in the form of interferences in the family routine, leisure, and recreation. This results in social, marital, familial, and emotional problems. The parental stress in caregiving of a child with ID is well known.[8,26] This is reiterated by maximum of our participants who reported the disability of their child to be a major concern undermining other things in life. Parental coping styles are important determining factors and can impact the level of parental distress.[27] We set out to investigate this relationship further, as to what is the impact of different coping styles on the manifestation of psychopathology in parents of children with ID.

Majority of the children were males and reflects the male-biased population ratio of the Indian population in general, and the mean age of participants as well as the children was comparable to the recent studies from the region.[9,11] The highest people with ID are of mild category and account for 85% of the intellectually disabled followed by moderate (10%), severe (3%–4%), and profound (1%–2%).[3]

Most of the parents perceived their child's disability to be a major concern in their life emphasizing how much a parent's life revolves around their child and affected by the disability of child. The fantasies of the ideal child and its disillusionment is normal in parenting but when this disillusionment is too large to handle that leaves the parents too anxious and worried.[28] Parental stress affects the psychological well-being of the parents[26] and adversely affects the family.[29] Worry, guilt, sadness, fatigue, embarrassment, resentment, and anger directed toward the child are indications of parent's distress.[30] The psychopathology manifested in our sample is more of neurotic spectrum (somatization, obsessive-compulsive, depression and anxiety, etc.) than of psychotic spectrum (paranoid ideation, psychoticism, etc.). Depression and somatization were the common psychopathologies in our sample. Whereas depression is very common in parents of children with ID in the Indian subcontinent,[9] similar findings were reflected in mothers of children with mental health problems.[31] Somatization is a clinical presentation of distress with more emphasis on somatic complaints than psychological mode.[32] The mean somatization score and general symptoms index which suggest that the overall distress level was comparable with a Turkish study of mothers of intellectually disabled children.[13]

We found mothers having more IPS and depression than fathers. The emotional and social needs of Indian mothers of child with ID are higher than fathers,[33] is which probably because of higher involvement and of mother in raising the child in typical Indian household. Depression scores are higher in mothers than fathers of child with ID in recent studies from Indian subcontinent.[9,11] Similarly, the mothers of child with moderate to profound ID have higher anxiety levels than the fathers; however, it does not differ much in parents of mild or borderline ID.[7]

The parents of girl child are perceived to have more needs than parents of the male child.[33] In our study, the parents of the male child had comparable scores on most psychopathology subscales with few significant differences which are not in keeping with this view. Another Vietnamese study suggests that the stress of parenting a girl child with a developmental disability is higher than the male child[34] and later Pakistani research is in agreement with this view.[35] On the counter-argumentative view, India is a patriarchal society and parents traditionally look up to their son to take care of them in their late life; these expectations are shattered for parents of a male child with ID in many cases. Parenting a male child with ID is more stressful than parenting a female child in a patriarchal society of Indian subcontinent.[5]

The severity of ID may not interfere with the psychopathology. The ID in itself is such an overwhelming experience for parents that the severity of the disability is inconsequential.[33] Azeem et al. found association between severity of ID and depression, anxiety in mothers but not fathers.[9] Similarly, an Indian investigation[7] suggested higher anxiety levels in parents of profound to moderate intellectually disabled children than mild ones. The psychopathology in parents of intellectually disabled is more complex, with outcome determined not just by severity of ID but other multiple factors. Psychiatric symptomatology of parents is associated with higher level of dysfunction in children[8] and may pose a greater challenge to parents. Similarly, the parental psychopathology is argued to be associated with behavioral problems of the child.[36] Our analysis did not consider behavior problems associated with ID for the study but included severity grades of ID. Our results suggest that psychopathology is independent of severity of ID of child.

As the child gets older, the parents understand the disability and their need for management, emotionality, physical care and balancing family relationship decreases[33] and there is no association between psychopathology and age of the child.[5] There is lesser psychopathology in older parents as suggested from our results. Firat et al. find higher depression scores in younger mothers of children with autism and higher anxiety scores in older mothers of children with ID.[13] Older parents do not consider the child as the cause of problems but are spiritual and have an emotional attachment to him/her at the same time concerned about the future of child after them.[37]

Coping is a way of stress management. It includes task-oriented and ego defense mechanisms, responses of individual to stressful situations, and the factors that enable an individual to regain emotional equilibrium after a stressful experience. In this scale emotion-focused coping are Escape avoidance, fatalism, and passivity; and expressive action, Problem-solving is problem-focused coping mechanisms. Folkman[38] maintains that both emotion-focused and problem-focused coping are helpful in reevaluation of the stressor. However, emotion-focused coping is believed to be associated with an unsatisfactory outcome and problem-focused coping is associated with a more satisfactory outcome.[5] Problem-focused coping is known to improve mental health outcome in mothers of child with Down syndrome.[39] The general psychopathology and distress which is measured by GSI is positively correlated with emotion-focused coping mechanisms fatalism and passivity as well as problem-focused coping mechanism expressive action. The fatalism and passivity have a negative outcome and are associated with higher psychopathology in parents of chronically ill children.[21] Acceptance and optimism are found to be protective towards parental stress.[40]

CONCLUSION

The current study has unfolded psychological issues of parents of children with ID. It was found that mothers were having more psychopathology than fathers as they are more actively involved in childcare. The ID of child is a great concern to parents and depressive, somatic complains are common. The parental psychopathology was not associated with severity of ID of the child. Fatalism, passivity, and expressive action are the coping mechanisms associated with worse outcome regarding general dysfunction of the parents. The study had a view at parents who undergo stressful condition in raising their child with special needs. It is necessary and advisable to address the psychological problems of these parents. Equipping parents to have better-coping strategies would help in alleviating the psychopathology. Whenever an intellectually disabled child comes for consultation, it should be seen and treated as a family unit giving attention to parent's psychological needs as well. This will improve the outcome of the child, parents, and family life by decreasing caregiver burden.

Few limitations of our study are its cross-sectional design, consecutive, and hospital-based sampling. We also did not diagnose the parents on formal ICD or DSM classification as part of this study; however, each parent was encouraged to seek a formal opinion and management from our adult psychiatry outpatient department of our hospital.

Future directions: The psychological distress among the parents of ID as well as other developmental disabilities should be studied regarding distress and beyond anxiety-depression. Various determinants of distress need to be focussed on including but not limited to coping, social support, behavioral problems, and comorbidities of the child.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Abhijeet Faye and Dr. Rajeev Swamy for their continuous encouragement and support

The patients who consented for the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, Dua T, Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:419–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakhan R, Ekúndayò OT, Shahbazi M. An estimation of the prevalence of intellectual disabilities and its association with age in rural and urban populations in India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6:523–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.165392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King BH, Toth KE, Hodapp RM, Dykens EM. Intellectual disability. In: Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplam & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. New Delhi: Wolters Kluwer (India) Pvt. Ltd; 2009. pp. 3444–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maulik PK, Harbour CK. Epidemiology of intellectual disability. In: Stone JH, Blouin M, editors. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. 1st ed. Buffalo: Centre for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheikh MH, Ashraf S, Imran N, Hussain S, Azeem MW. Psychiatric morbidity, perceived stress and ways of coping among parents of children with intellectual disability in Lahore, Pakistan. Cureus. 2018;10:e2200. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassall R, Rose J, McDonald J. Parenting stress in mothers of children with an intellectual disability: The effects of parental cognitions in relation to child characteristics and family support. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49:405–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majumdar M, Da Silva Pereira Y, Fernandes J. Stress and anxiety in parents of mentally retarded children. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:144–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.55937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khamis V. Psychological distress among parents of children with mental retardation in the United Arab Emirates. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:850–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azeem MW, Dogar IA, Shah S, Cheema MA, Asmat A, Akbar M, et al. Anxiety and depression among parents of children with intellectual disability in pakistan. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:290–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das A, Jain P, Kale VP. A cross-sectional study to assess anxiety and depression in parents of children with intellectual disability. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:S125. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_259_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouhan SC, Singh P, Kumar S. A comparative study of anxiety and depressive symptoms among parents of mentally retarded children. J Well Being. 2016;10:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:121–6. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firat S, Diler RS, Avci A, Seydaoglu G. Comparison of psychopathology in the mothers of autistic and mentally retarded children. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:679–85. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.5.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derogatis LR, Unger R. Symptom checklist-90-revised. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. 2010;30:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groth-Marnat G. Handbook of Psychological Assessment. 5th ed. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 579–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, Baumann BD, Baity MR, Smith SR, et al. Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1858–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitz N, Kruse J, Heckrath C, Alberti L, Tress W. Diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: The general health questionnaire (GHQ) and the symptom check list (SCL-90-R) as screening instruments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:360–6. doi: 10.1007/s001270050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parikh RM, Quadros TS, D'Mello M, Anguir R, Jain R, Khambatta F. Mechanisms of coping and psychopathology following Latur earthquake: The profile study. Bombay Psychiatr Bull. 1993;5:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinto C, Lele MV, Joglekar AS, Panwar VS, Dhavale HS. Stressful life-events, anxiety, depression and coping in patients of irritable bowel syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:589–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao P, Pradhan PV, Shah H. Psychopathology and coping in parents of chronically Ill children. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:695–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02730656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creado DA, Parkar SR, Kamath RM. A comparison of the level of functioning in chronic schizophrenia with coping and burden in caregivers. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:27–33. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somaiya M, Kolpakwar S, Faye A, Kamath R. Study of mechanisms of coping, resilience and quality of life in medical undergraduates. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;31:19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faye A, Kalra G, Subramanyam A, Shah H, Kamath R, Pakhare A. Study of marital adjustment, mechanisms of coping and psychopathology in couples seeking divorce in India. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2013;28:257–69. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faye A, Tadke R, Gawande S, Kirpekar V, Bhave S, Pakhare A, et al. Assessment of resilience and coping in undergraduate medical students: A need of the day. J Educ Technol Health Sci. 2018;5:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Psychological well-being of caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities: Using parental stress as a mediating factor. J Intellect Disabil. 2011;15:101–13. doi: 10.1177/1744629511410922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dabrowska A, Pisula E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54:266–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hugger L. Mourning the loss of the idealized child. J Infant Child Adolesc Psychother. 2009;8:124–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayat M, Salehi M, Bozorgnezhad A, Asghari A. The comparison of psychological problems between parents of intellectual disabilities children and parents of normal children. World Appl Sci J. 2011;12:471–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brannan AM, Heflinger CA. Distinguishing caregiver strain from psychological distress: Modeling the relationships among child, family, and caregiver variables. J Child Fam Stud. 2001;10:405–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerkensmeyer JE, Perkins SM, Day J, Austin JK, Scott EL, Wu J, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms when caring for a child with mental health problems. J Child Fam Stud. 2011;20:685–95. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: Syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verma RK, Kishore MT. Needs of Indian parents having children with intellectual disability. Int J Rehabil Res. 2009;32:71–6. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32830d36b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin J, Nhan NV, Crittenden KS, Hong HT, Flory M, Ladinsky J. Parenting stress of mothers and fathers of young children with cognitive delays in vietnam. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50:748–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabih F, Sajid WB. There is significant stress among parents having children with autism. J Rawalpindi Med. 2008;33:214–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallagher S, Phillips AC, Oliver C, Carroll D. Predictors of psychological morbidity in parents of children with intellectual disabilities. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:1129–36. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamedanchi A, Khankeh HR, Fadayevatan R, Teymouri R, Sahaf R. Bitter experiences of elderly parents of children with intellectual disabilities: A phenomenological study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21:278–83. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.180385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folkman S. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. Stress: appraisal and coping; pp. 1913–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Azadfallah P, Hemmati Garakani S, Bakhshi E. The effect of problem-focused coping strategy training on psychological symptoms of mothers of children with down syndrome. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:254–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norizan A, Shamsuddin K. Predictors of parenting stress among malaysian mothers of children with down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54:992–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]