Abstract

Background:

There is limited number of studies from India investigating role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). This clinic-based study reports on the efficacy of rTMS as an add-on treatment in patients suffering from TRD.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-two right-handed patients suffering from major depressive disorder who failed to respond to adequate trials of at least two antidepressants drugs in the current episode received rTMS as an augmenting treatment. High-frequency (Hf) rTMS at 110% of the estimated resting motor threshold (MT) was given over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). A total of 15 sessions were given over 3 weeks with 3000 pulses per session. The outcome was assessed based on the changes in scores of Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression or Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

Results:

There was a significant reduction in final assessment scores after rTMS intervention as compared to baseline with almost 50% of the participants showing response in either scale.

Conclusion:

Hf rTMS applied over left DLPFC is an effective add-on treatment strategy in patients with TRD.

Key words: Brain stimulation, depression, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation

INTRODUCTION

Depression is one of the most prevalent and disabling disorders worldwide. Unipolar major depression accounts for 4.3% of the global burden of disease and is the third leading cause of disease burden, which is projected to be leading cause of disease burden globally by the year 2030.[1] Indian data estimates the prevalence of depression to be about 15%, similar to the worldwide literature.[2]

Wide ranges of treatment options are available for depression ranging from biological treatments to psychotherapy, but despite all therapeutic options a significant proportion of patients fail to respond to these treatments. Different studies have shown that even if conservative estimates are taken, almost one-fifth of the patients continue to suffer from depression after multiple drug trials.[3] Several published randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis have shown repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to be an effective treatment modality in the management of patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression (TRD). The majority of studies have targeted left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) as an area of stimulation since several studies have shown that patients suffering from depression have decreased neuronal activity as well as decreased metabolism in these regions or in the regions closely connected to them like rostral anterior cingulate cortex.[4,5] High frequency (Hf) rTMS have been shown to increase the local cortical neuronal activity and modulate the activity of local inhibitory circuits. It can bring changes in the levels of neurotransmitters as well as increase the local brain metabolism.[6]

There have been only few published studies from India investigating the role of rTMS in depression. This paper reports on the efficacy of rTMS as an add-on treatment in patients who were suffering from TRD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, runs a rTMS clinic once a week where detailed evaluation of patients suffering from various psychiatric disorders is done to assess their suitability for this intervention and rTMS sessions are given in the Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation laboratory for 5 days a week. In this paper, we are reporting clinic-based data of group of patients who were suffering from major depressive disorder according to the International Classification of Diseases version 10 and completed 15 sessions of rTMS between August 2009 and December 2015. These patients failed to respond to at least two antidepressant medication trials given for at least 6–8 weeks at adequate dose. All the patients undergoing the rTMS intervention were screened on a pro forma for having any condition that can preclude the safe use of rTMS and were excluded if they suffered from any such condition. Informed consent was taken as a routine procedure before treatment initiation. There were no limits for number of lifetime antidepressant drug failures in the patients. They were continued on the last drug combination, which they were receiving, and no changes were made to it for the period in which the sessions were being given.

The rTMS intervention was administered using a 70-mm figure-of-8 thin air-film coil for 5 days a week for consecutive 3 weeks. The stimulation parameter used was of high frequency (15 Hz) stimulation at 110% of the estimated resting motor threshold (rMT). The scalp position of lowest MT for the right abductor pollicis brevis muscle was determined using single-pulse TMS defining the rMT by the lowest power setting producing a visible muscle contraction in ≥5 of 10 trials. All the participants received 3000 pulses per session with pulse frequency of 10 pulses per second. The area of stimulation was left DLPFC, which was identified at 5 cm anterior from the MT location, along a left superior oblique plane corresponding to Fp3 area as per international 10–20 electroencephalography system.

The assessments were carried out at baseline (just before starting the first session) and after 15 sessions using either the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) or Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). The outcome measures were mean change in scale scores after rTMS intervention and percentage of patients who responded to treatment (more than 50% reduction in baseline scores).

Analysis was done using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, version 21.0; www.spss.com, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive variables were assessed using measures of central tendency and differences among the categorical and continuous variables were assessed using Chi-square test or Student's t-test respectively. Paired t-test was applied to assess the change in scale scores from baseline to final session. We also assessed the composite percentage score change combining the percentage change of scores for both scales for an overall estimate of percentage change for the study population.

RESULTS

Overall, there were 22 participants who had completed 15 sessions of rTMS for management of depression during the period of analysis with significant majority belonging to male gender (male, female = 72.7% [n = 16], 27.3% [n = 6]; P = 0.03).

The mean age of the sample was 46.09 ± 15.22 years (range: 25–76) with no significant difference among the genders (male, female = 43.94 ± 16.53, 51.83 ± 9.93 years; P = 0.08). Overall, the age distribution of the study sample was not clustered when plotted against change in assessment scores suggesting that there was no impact of age over assessment scores.

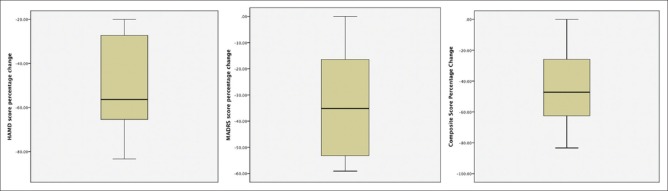

Out of the 22 participants, the outcome has been assessed over HAMD and MADRS in 14 and 8 participants, respectively. There was a significant reduction in final assessment scores over both scales (HAMD and MADRS) after rTMS intervention as compared to baseline [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean score change in assessment parameters after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation intervention

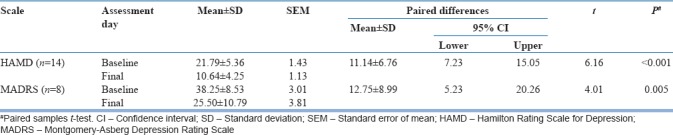

There were no differences in overall percentage change in assessment parameters among the genders (male, female = −42.87 ± 23.11, −46.53 ± 20.67; P = 0.73; 95% confidence interval = −18.83, 26.16) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Gender differences in percentage score change (male:female = 16:6)

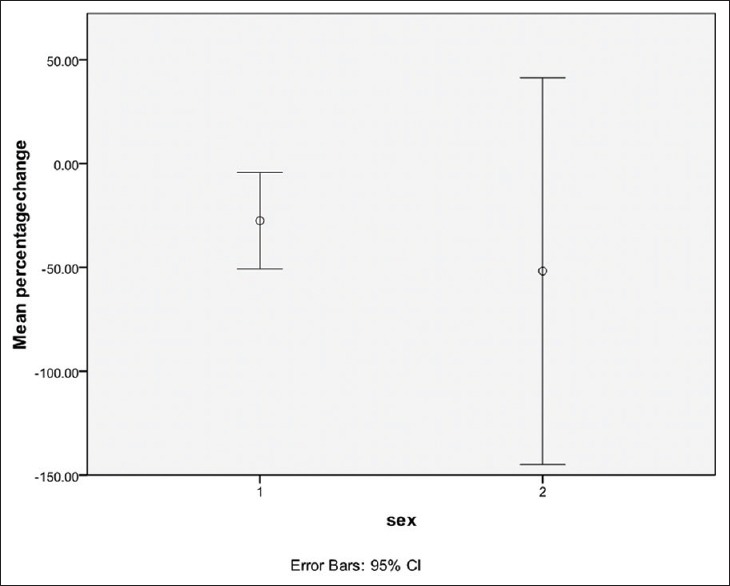

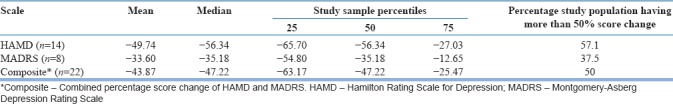

When assessing for the percentage change in scores, an improvement of more than 50% score change was observed in 57% of participants assessed over HAMD and 37% participants assessed over MADRS [Table 2]. On combining the percentage change of scores in both scales for the study population (composite scores), about 50% subjects had an improvement of more than 50% in either scale scores [Figure 2]. Thus, it can be asserted that there was a response rate of about 50% in the overall sample population with more changes observed in subjects being assessed over HAMD.

Table 2.

Percentage change in assessment parameters after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation intervention

Figure 2.

Box plot of percentage change of scores in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale and composite scores after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation intervention

DISCUSSION

In the current study, there was significant reduction in final assessment scores over both scales (HAMD and MADRS) and about 50% of the patient could be classified as “responders” after receiving rTMS. These findings resemble findings observed in similar studies using rTMS for TRD worldwide. In a study reporting the effectiveness of TMS in clinical practice in about 100 patients, a response rate of 50% was seen which is similar to our finding.[7] Similarly, a multi-site naturalistic study reporting data for 307 patients found the response rate to be almost 60%.[8] A recent meta-analysis which included seven RCTs and evaluated the efficacy of rTMS when used as an augmentative strategy in TRD found the response rate to be 46% and concluded that in patients who fail anti-depressant drug trial, augmentation with rTMS can significantly increase the effect of antidepressants and is a safe strategy with low adverse event and dropout rates.[9] One of the studies found that using higher stimulation intensity and clinical features like having less severe depression at baseline, shorter duration of current episode, and having recurrent episode rather than first episode predicted better response rates to TMS in patients suffering from depression.[10] Although most of the studies have used high-frequency stimulation and have targeted left DLPFC, there is significant heterogeneity in the stimulation parameters and site of stimulation making comparison across different studies difficult.[11] It is therefore important that a guideline should be developed about the stimulation parameters that would be most beneficial for patients suffering from depression. A recent meta-analysis found that in the absence of maintenance treatment the effect of TMS was short lasting and the magnitude of the antidepressant effect during follow-up was small.[12] It is important to develop maintenance protocols for the patients who have obtained acute benefit from TMS. Protocols can consider using only TMS-based intervention without pharmacotherapy as some studies have shown that administrating TMS even once or twice a week can maintain the beneficial effects obtained by it.[13,14]

There is dearth of published data from India investigating the role of TMS in depression that could be due to limited number of mental health centers having such facility. In an Indian study, rTMS not only produced antidepressant effects equivalent to medications but also “corrected” the autonomic imbalance after 2 weeks of therapy.[15] In another sham-controlled study in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder, there was an improvement in depressive symptoms noticed in active group receiving Hf rTMS at the right prefrontal area (10 Hz, 110% of MT, 4s per train, 20 trains per session) compared to sham group.[16] Another sham-controlled study in moderate-to-severe depression assigned patients to receive add-on, active-priming rTMS (4–8 Hz; 400 pulses, at 90% of MT) or sham-priming stimulation followed by low-frequency rTMS (1-Hz; 900 pulses at 110% of MT) over the right DLPFC and found that the prestimulation with frequency-modulated priming stimulation in the theta range has greater antidepressant effect than low-frequency stimulation alone.[17] In a sham-controlled RCT conducted over short duration of 2 weeks rTMS, it was seen that the treatment with rTMS did not show improvement.[18] In one open-label trial delivering Hf rTMS at 10 Hz given over left DLPFC at 110% MT, there was a significant reduction in mean HAMD scores. Case report of maintenance treatment using rTMS has also been mentioned.[19] In a recently reported study using single-photon emission computed tomography-guided rTMS compared to rTMS at left DLPFC, the former group had better response than latter.[20]

The current study has limited number of inclusion and exclusion criteria thereby closely resembling the practice in real clinical world. Real-world clinical data can help in bridging findings obtained with more narrowly defined patient populations in the randomized controlled trials to the anticipated effects of a treatment when used in a typical practice setting.

The study further potentiates the finding that failure to respond to one or more antidepressant medication trials does not preclude a favorable response to rTMS. On the other hand, medication resistance may also predict poorer clinical outcome of rTMS as about 50% of patients had a less than 50% change in percentage scale scores. As has been observed in studies using electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), patients who have not responded to one or more adequate antidepressant medication trials have a lower probability of response to ECT as compared to patients treated with ECT without having received an adequate medication trial.[21,22]

The present study shows that the beneficial effect of TMS in Indian patients suffering from depression is similar to those in western settings. However, generalization of findings from the study is limited due to lack of a control group, small sample size, retrospective data analysis, and lack of better localization techniques. Since we had included only patients who had completed the required treatment protocol (i.e., 15 sessions), the issue of tolerability and nonresponder bias remains to be assessed among the participants receiving <15 sessions or treatment dropouts. Future studies should regard these caveats and do a follow-up of the data for ascertaining the remission and recovery rates in treatment responders. Predictors of response also need to be determined in such studies.

CONCLUSION

This clinical data show the effectiveness of Hf rTMS applied over the left DLPFC in TRD. Approximately 50% persons with TRD responded to the intervention after completing 15 sessions. The report supports further investigation into the potential therapeutic applications of rTMS in TRD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Document EB130.R8. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Global Burden of Mental Disorders and the Need for Comprehensive, Coordinated Response from Health and Social Sectors at the Country Level. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poongothai S, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Mohan V. Prevalence of depression in a large urban South Indian population – The Chennai urban rural epidemiology study (CURES-70) PLoS One. 2009;4:e7185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trevino K, McClintock SM, McDonald Fischer N, Vora A, Husain MM. Defining treatment-resistant depression: A comprehensive review of the literature. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2014;26:222–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayberg HS. Modulating dysfunctional limbic-cortical circuits in depression: Towards development of brain-based algorithms for diagnosis and optimised treatment. Br Med Bull. 2003;65:193–207. doi: 10.1093/bmb/65.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeken C, De Raedt R. Neurobiological mechanisms of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the underlying neurocircuitry in unipolar depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:139–45. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/cbaeken. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald PB, Daskalakis ZJ. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Treatment for Depressive Disorders: A Practical Guide. United States: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2014. pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connolly KR, Helmer A, Cristancho MA, Cristancho P, O'Reardon JP. Effectiveness of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice post-FDA approval in the United States: Results observed with the first 100 consecutive cases of depression at an academic medical center. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:e567–73. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, Boyadjis T, Brock DG, Cook IA, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: A multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:587–96. doi: 10.1002/da.21969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu B, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Li L. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as an augmentative strategy for treatment-resistant depression, a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham-controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:342. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0342-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Anderson RJ, Daskalakis ZJ. A study of the pattern of response to rTMS treatment in depression. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:746–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Quality Ontario. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: A Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2016;16:1–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kedzior KK, Reitz SK, Azorina V, Loo C. Durability of the antidepressant effect of the high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the absence of maintenance treatment in major depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:193–203. doi: 10.1002/da.22339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Reardon JP, Blumner KH, Peshek AD, Pradilla RR, Pimiento PC. Long-term maintenance therapy for major depressive disorder with rTMS. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1524–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reshetukha T, Alavi N, Milev R. Maintenance repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in relapse prevention of depression. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:836. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Udupa K, Sathyaprabha TN, Thirthalli J, Kishore KR, Raju TR, Gangadhar BN, et al. Modulation of cardiac autonomic functions in patients with major depression treated with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Affect Disord. 2007;104:231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkhel S, Sinha VK, Praharaj SK. Adjunctive high-frequency right prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was not effective in obsessive-compulsive disorder but improved secondary depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:535–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nongpiur A, Sinha VK, Praharaj SK, Goyal N. Theta-patterned, frequency-modulated priming stimulation enhances low-frequency, right prefrontal cortex repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in depression: A randomized, sham-controlled study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:348–57. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.3.jnp348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lingeswaran A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression: A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Indian J Psychol Med. 2011;33:35–44. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.85393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterjee B, Kumar N, Jha S. Role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in maintenance treatment of resistant depression. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:286–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha S, Chadda RK, Kumar N, Bal CS. Brain SPECT guided repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in treatment resistant major depressive disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;21:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, Malone KM, Pettinati HM, Stephens S, et al. Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:985–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapira B, Lidsky D, Gorfine M, Lerer B. Electroconvulsive therapy and resistant depression: Clinical implications of seizure threshold. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]