Abstract

Skeletal muscle rapidly remodels in response to various stresses, and the resulting changes in muscle mass profoundly influence our health and quality of life. We identified a diacylglycerol kinase ζ (DGKζ)–mediated pathway that regulated muscle mass during remodeling. During mechanical overload, DGKζ abundance was increased and required for effective hypertrophy. DGKζ not only augmented anabolic responses but also suppressed ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS)–dependent proteolysis. We found that DGKζ inhibited the transcription factor FoxO that promotes the induction of the UPS. This function was mediated through a mechanism that was independent of kinase activity but dependent on the nuclear localization of DGKζ. During denervation, DGKζ abundance was also increased and was required for mitigating the activation of FoxO-UPS and the induction of atrophy. Conversely, overexpression of DGKζ prevented fasting-induced atrophy. Therefore, DGKζ is an inhibitor of the FoxO-UPS pathway, and interventions that increase its abundance could prevent muscle wasting.

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle can change its protein content and size in response to various factors including physical activity, nutritional status, nerve injuries, diseases, and aging (1, 2). Comprising about 45% of total body mass, this highly plastic tissue not only serves as the motor that drives locomotion but also plays a critical role in whole-body metabolism (such as in glucose homeostasis) (3, 4). Hence, changes in skeletal muscle mass have a great impact on our health and quality of life, and the failure to maintain muscle mass is one of the leading risk factors for morbidity and mortality (5, 6).

During remodeling, changes in skeletal muscle mass are driven by the balance between the rate of protein synthesis and the rate of protein degradation. Hence, a net positive balance leads to muscle growth, whereas a net negative balance leads to muscle loss. The regulation of protein synthesis and protein degradation is largely driven by a rapamycin-sensitive protein kinase called mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), respectively (7). Signaling by mTOR regulates protein synthesis primarily through the phosphorylation of its substrates such as eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)–binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6k) (8–10). Specifically, phosphorylated 4E-BP1 dissociates from eIF4E, allowing eIF4E to associate with eIF4G and thereby promoting eIF4F complex formation and cap-dependent initiation of translation. The UPS regulates protein degradation primarily through the E3 ligase–mediated ubiquitination of protein substrates that are targeted to the 26S proteasome complex (11). For example, in skeletal muscle, the ubiquitination of myofibrillar proteins is mediated by muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases that are increased in abundance under various remodeling conditions, such as muscle atrophy F-box (MAFbx) and muscle RING finger 1 (MuRF1) (12). Given the important roles of mTOR signaling and the UPS in determining muscle protein turnover, unraveling the molecular mechanisms that regulate these two processes should facilitate the development of therapies that can preserve and/or increase muscle mass.

Mechanical loading, such as resistance exercise, promotes an increase in mTOR signaling, protein synthesis, and skeletal muscle mass (13). Accordingly, various models of mechanical loading have been used to identify the molecular mechanisms that are responsible for these anabolic events. For instance, we have found using an ex vivo passive stretch model that diacylglycerol (DAG) kinase ζ (DGKζ) plays an important role in the mechanical activation of mTOR signaling by promoting the synthesis of the mTOR agonist phosphatidic acid (PA) from DAG (14–16). Moreover, we and others have shown that PA supplementation or DGKζ overexpression is sufficient to promote an increase in protein synthesis and fiber size, respectively (14, 15,17). Furthermore, the extent of resistance exercise–induced muscle hypertrophy is positively associated with pretraining levels of skeletal muscle DGKζ mRNA expression (18). On the basis of these points, it is plausible that DGKζ enhances mTOR signaling, protein synthesis, and fiber size during mechanically induced skeletal muscle remodeling. Therefore, we sought to examine the role of DGKζ in the activation of mTOR signaling, protein synthesis, and muscle growth during mechanical overload, a commonly used animal model of resistance exercise. However, our results revealed that DGKζ not only functioned to promote mTOR signaling and protein synthesis but also acted as an inhibitor of the UPS and protein degradation through a mechanism involving forkhead box protein O (FoxO). Our results also demonstrated that increased expression of DGKζ mitigated various types of fiber atrophy, thus identifying DGKζ as a potential therapeutic target for the prevention of muscle wasting.

RESULTS

During mechanical overload, DGKζ is predominantly increased among DGK isoforms

The DGKζ-dependent synthesis of PA is implicated in the mechanical activation of mTOR signaling (14, 15). To assess the possible involvement of this mechanism in an in vivo model, rat plantaris muscles were subjected to mechanical overload. Rats were used in this experiment because they could provide the amount of tissue needed for the in vivo measurement of total PA. After 7 days, mechanical overload induced muscle growth, increased the levels of DAG and PA, and activated mTOR signaling (as revealed by the phosphorylation of p70S6k on Thr389) (fig. S1, A to D). Furthermore, the increase in DAG-PA-mTOR signaling was associated with an increase in total DGK activity and in membrane-associated DGKζ activity (fig. S1, E and F). Together, these data suggest that a DGKζ-dependent synthesis of PA from DAG could contribute to the overload-induced activation of mTOR signaling.

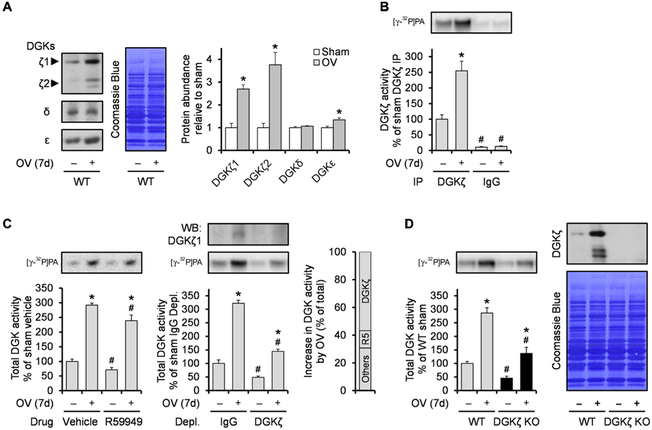

In this set of experiments, we also found that total DGK activity increased in both whole homogenate and cytosolic fractions (fig. S1E). Thus, we envisioned that mechanical overload not only induced membrane translocation of DGKζ but also increased its protein abundance. Consistent with this possibility, the ζ isoform, but not the δ or ε isoforms of DGK, substantially increased in response to mechanical overload in mice (Fig. 1A). Note that DGKζ has two splice variants in mice, with DGKζ1 predominating over DGKζ2 in skeletal muscle. The increase in DGKζ protein was also accompanied by a similar increase in DGKζ activity (Fig. 1B). Although δ, ε, and ζ isoforms of DGK are highly abundant in skeletal muscle, there are still other DGK isoforms whose expression could also have increased in response to mechanical overload (19). To determine the extent to which these other DGK isoforms may have increased, we measured total DGK activity from whole homogenates that were pretreated with R59949, which preferentially inhibits the α, β, γ, and θ isoforms of DGK (20, 21). R59949-sensitive DGK isoforms accounted for only a small portion (~13%) of the overload-induced increase in total DGK activity (Fig. 1C). In contrast, immunodepletion of DGKζ decreased the overload-induced increase in total DGK activity by ~60% (Fig. 1C). Similar results were also obtained when we compared total DGK activity in muscles from wild-type (WT) and DGKζ knockout (KO) mice (Fig. 1D). Combined, these results indicate that among all the DGK isoforms, mechanical overload predominantly increases DGKζ expression.

Fig. 1. DGKζ is predominantly increased among DGK isoforms during mechanical overload.

WT and DGKζ KO mice were subjected to mechanical overload (OV+) or sham (OV−) surgery and the plantaris muscles (n) were collected at 7 days (7d) after surgery. (A to C) WT muscles were subjected to Western blotting (WB) to detect the indicated proteins (n = 4 from three mice per group) (A) or to DGK activity assay after immunoprecipitation (IP) of DGKζ (n = 3 to 4 from three mice per group) (B), in vitro treatment of R59949 (R5), or immunodepletion (Depl.) of DGKζ (n = 3 to 4 from three mice per group) (C). (D) WT and DGKζ KO muscles were subjected to Western blotting to detect DGKζ protein (right) or to DGK activity assay (left) (n = 4 to 6 from three mice per group). Values were expressed as means + SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to sham within the same immunoprecipitation (B), drug (C), immunodepletion (C), or genotype (D); #P < 0.05 compared to DGKζ (B), vehicle (C), IgG (C), or WT (D), within the same surgery, Student’s t test (A) or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (B to D).

DGKζ is required for effective muscle growth during mechanical overload

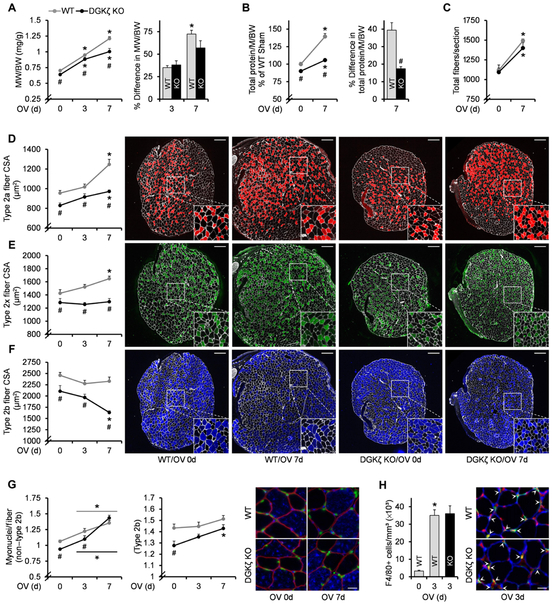

To determine the role of DGKζ in mechanical overload–induced skeletal muscle growth, we first measured muscle mass in WT and DGKζ KO mice after the onset of mechanical overload. DGKζ KO mice not only exhibited smaller basal muscle mass but also showed an impairment in mechanical overload–induced increase in muscle mass (Fig. 2A and table S1). The impaired increase in muscle mass was not due to artifacts, such as reduced edema, because the accumulation of total protein by mechanical overload was also impaired in DGKζ KO muscles (Fig. 2B). In addition to individual muscle fiber hypertrophy, an increase in muscle mass during mechanical overload can also be achieved by hyperplasia, which is an increase in the number of muscle fibers (22). However, as indicated by the total number of fibers per muscle cross section, muscle hyperplasia was not altered in DGKζ KO mice, suggesting that the impaired increase in muscle mass was likely due to a reduction in fiber hypertrophy (Fig. 2C). Hence, we compared the cross-sectional area (CSA) of different muscle fiber types during mechanical overload. As previously reported, mechanical overload induced fiber type–dependent increases in the CSA of WT muscles (23). Specifically, the CSA of non–type 2b fibers (type 2a and type 2x fibers) progressively increased after the onset of mechanical overload, whereas the CSA of type 2b fibers was not significantly altered (Fig. 2, D to F). However, in DGKζ KO muscles, the increase in CSA of non–type 2b fibers was severely blunted, and the CSA of type 2b fibers was actually reduced after 7 days of mechanical overload (Fig. 2, D to F). The type 2b fiber atrophy that occurred during mechanical overload in the absence of DGKζ was also confirmed when we used mechanical overload of the extensor digitorum longus muscles instead of the plantaris (fig. S2). Together, these results demonstrate that DGKζ is necessary for effective non–type 2b fiber hypertrophy and the maintenance of type 2b fiber size, thereby contributing to the growth that occurs during mechanical overload.

Fig. 2. DGKζ is required for effective muscle growth during mechanical overload.

WT and DGKζ KO mice were subjected to mechanical overload (3d or 7d) or sham (0d) surgery, and the plantaris muscles (n) were collected at 3 or 7 days after surgery. (A) Muscle weight (MW)–to–body weight (BW) ratio (n = 6 to 8 from three to five mice per group). (B) Total protein content per muscle (M) normalized by BW (n = 5 to 6 from five to six mice per group). (C to F) Immunohistochemistry on cross sections with antibodies against laminin and type 2a myosin heavy chain (MHC), type 2× MHC, or type 2b MHC, to measure total fiber number per section (n = 6 to 9 from three to five mice per group) (C), and CSA in type 2a fibers (D), type 2× fibers (E), and type 2b fibers (F). For (D) to (F) (n = 5 to 8 from three to five mice per group), the right panels show representative images of the whole cross sections and their 2× magnified views (white, laminin; red, type 2a MHC; green, type 2× MHC; blue, type 2b MHC). Scale bars, 200 μm. (G) Immunohistochemistry on cross sections with propidium iodine (PI) and antibodies against dystrophin and type 2b MHC to measure the number of myonuclei (nuclei inside the dystrophin ring) per fiber cross section in non–type 2b fibers and type 2b fibers (n = 5 to 8 from three to four mice per group). The right panel shows representative images (red, dystrophin; blue, type 2b MHC; green, PI). Scale bar, 20 μm. (H) Immunohistochemistry on cross sections with PI and antibodies against laminin and F4/80 to measure the density of macrophages (as determined by nuclei colocalized with F4/80 outside the laminin ring) (n = 3 to 4 from three to four mice per group). The right panel shows representative images (red, PI; blue, laminin; green, F4/80). Scale bar, 20 μm. Values were expressed as means + SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to sham within the same genotype, #P < 0.05 compared to WT within the same surgery, two-way ANOVA (A to G) or Student’s t test (B, right, and H).

DGKζ contributes to the activation of protein synthesis and mTOR signaling and attenuates the activation of UPS-dependent protein degradation after the onset of mechanical overload

Skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy requires other cells that are immediately adjacent to the muscle fibers, such as fusion of satellite cells into muscle fibers leading to myonuclear accretion and macrophage infiltration (24,25). Because both satellite cells and macrophages in our DGKζ KO mice were also DGKζ-deficient, we considered the possibility that the antihypertrophic effects of DGKζ deficiency might be driven by impaired activation of these cells. However, DGKζ KO muscles exhibited a normal increase in the number of myonuclei and macrophages after mechanical overload (Fig. 2, G and H). Thus, the impaired mechanical overload–induced hypertrophy in muscles from DGKζ KO mice appears to be mediated by the absence of DGKζ in muscle fiber itself but not in other cells.

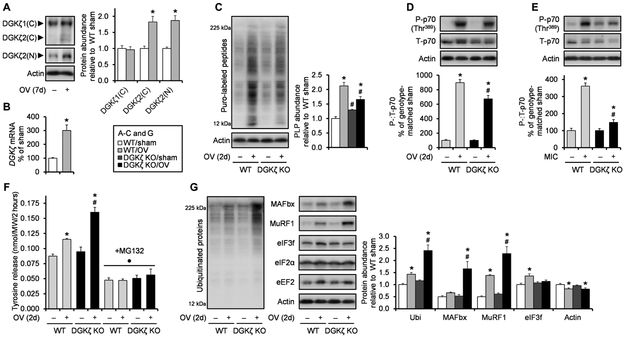

During mechanical overload, the rates of both protein synthesis and protein degradation increase as muscles undergo the process of remodeling; however, because the increase in protein synthesis exceeds that of protein degradation, overloaded skeletal muscles eventually increase their mass through the accretion of new proteins. Hence, to further interrogate the mechanisms through which DGKζ contributes to the overload-induced protein accumulation and muscle growth, we measured several anabolic and catabolic events at a time point that preceded the onset of significant hypertrophy (2 days). At this early time point, we first observed that mechanical overload increased only the protein amounts of the low-abundant form of DGKζ (DGKζ2), whereas DGKζ mRNA expression increased robustly (using a non–splice variant–specific measurement) (Fig. 3, A and B). Nevertheless, we found that the overload-induced increase in protein synthesis was considerably attenuated in DGKζ KO muscles (Fig. 3C). Consistently, the magnitude of mechanical overload–induced activation of mTOR signaling was also significantly blunted in DGKζ KO muscles, as indicated by the phosphorylation of p70 (at Thr389) and 4E-BP1 (at Thr36/45) and the association of eIF4E with 4E-BP1 or eIF4G (Fig. 3D and fig. S3A). We also confirmed the impaired activation of mTOR signaling by DGKζ KO in electrically stimulated maximal-intensity contractions, which is a more acute and better controlled model of resistance exercise, suggesting that the effects of DGKζ KO during mechanical overload was not due to a compromised increase in workload (Fig. 3E). Combined, these results demonstrate that DGKζ contributes to the overload-induced activation of mTOR signaling and protein synthesis.

Fig. 3. DGKζ contributes to the activation of mTOR signaling and protein synthesis and attenuates the activation of UPS-dependent protein degradation after the onset of mechanical overload.

WT and DGKζ KO mice were subjected to mechanical overload or sham surgery (A to D, F, and G), or a bout of maximal-intensity contractions (MIC+) or the control condition (MIC−) (E). The plantaris and tibialis anterior muscles (n) were collected at 2 days after surgery or immediately after MIC, respectively. (A) Western blotting to detect DGKζ protein with antibodies against the C terminus (C) or the N terminus (N; specific to splice variant 2) of DGKζ (n = 6 from three mice per group). (B) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to measure mRNA expression of DGKζ (n = 5 to 6 from three mice per group). (C) Measurement of protein synthesis rate as assessed by Western blotting of puromycin (puro)–labeled peptides (PLP) (n = 5 to 6 from three mice per group). (D and E) Western blotting to detect phosphorylated (P) and total (T) p70 [n = to 6 from three mice per group (D) and n = 3 to 4 from three to four mice per group (E)]. (F) Measurement of protein degradation rate as assessed by tyrosine release (n = 3 to 5 from three to five mice per group). (G) Western blotting to detect the indicated proteins (n = 5 to 8 from three to four mice per group). Values were expressed as means (+SEM in graphs). *P < 0.05 compared to sham within the same genotype, #P < 0.05 compared to WT within the same surgery (C, D, F, and G) or MIC+ (E), ·P < 0.05 compared to non-MG132 within the same genotype and surgery, Student’s t test (A to B) or two-way ANOVA (C to G). Ubi, ubiquitin.

We also found that the overload-induced increase in the rate of protein degradation was markedly augmented in DGKζ KO muscles (Fig. 3F). This is an interesting observation because the accelerated increase in protein degradation, in addition to the blunted increase in protein synthesis, further explains why DGKζ KO muscles showed an impaired net accumulation of protein and muscle growth. The degradation rate of most proteins in mammalian cells is determined through their rate of ubiquitination by E3 ubiquitin ligases and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome (26). Consistently, we found that the overload-induced increase in the rate of protein degradation and its augmentation by DGKζ KO were abolished by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, global ubiquitination and the protein abundance of two critical muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases, MAFbx and MuRF1, were increased by mechanical overload, and these increases were also augmented in DGKζ KO muscles (Fig. 3G). Moreover, unlike other translation factors, the protein abundance of eIF3f, a target of MAFbx (27), was increased only in WT muscles, supporting the functionality of the relatively large increase in the abundance of MAFbx in DGKζ KO muscles (Fig. 3G). Together, these results demonstrate that DGKζ is necessary to prevent an excessive increase in the UPS-mediated protein degradation during mechanical overload.

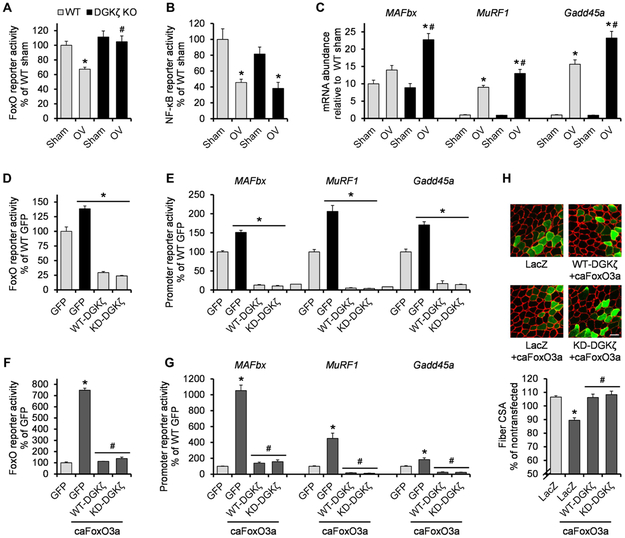

DGKζ suppresses FoxO activity and its target gene expression after mechanical overload

Our results revealed that DGKζ can attenuate protein degradation by suppressing key components of the UPS, such as MAFbx and MuRF1, during mechanical overload. MAFbx and MuRF1 gene expression can be activated by the transcription factors FoxO and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (12). Thus, we measured the activities of FoxO or NF-κB response element reporters transfected into plantaris muscles. Mechanical overload induced a noticeable decrease in the activity of both FoxO and NF-κB (Fig. 4, A and B). However, we found that the decrease in the activity of FoxO but not in that of NF-κB was lost in muscles from DGKζ KO mice (Fig. 4, A and B). Consistently, the mRNA expression of several FoxO target genes including MAFbx, MuRF1, and Gadd45a was augmented in DGKζ KO muscles after the onset of mechanical overload (Fig. 4C and fig. S3B). The inhibitory effects of DGKζ on FoxO activity and its target gene expression were not likely to be mediated by Akt, a FoxO inhibitor (28), because DGKζ KO did not reduce the phosphorylation and thus activation of Akt after mechanical overload (fig. S4A). Combined, these results indicate that DGKζ promotes mechanical overload–induced muscle growth, at least in part by suppressing FoxO activity and the transcription of its target genes.

Fig. 4. DGKζ counteracts FoxO activity.

(A to C) WT and DGKζ KO mice were subjected to mechanical overload or sham surgery, and the plantaris muscles (n) were immediately cotransfected with pRL-SV40 Renilla luciferase (pRL) and FoxO response element firefly luciferase reporter (n = 4 to 5 from four to six mice per group) (A), NF-κB response element firefly luciferase reporter (n = 4 to 6 from four to six mice per group) (B), or left nontransfected (n = 5 to 8 from three to four mice per group) (C). Transfected muscles were collected at 2 days after surgery and subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay. Nontransfected muscles were collected at 1 day after surgery and subjected to qRT-PCR to measure mRNA expression of the indicated genes. (D and E) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) from WT and DGKζ KO mice were cotransfected with GFP, hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged WT-DGKζ, or HA-tagged KD-DGKζ, and pRL and FoxO response element firefly luciferase reporter (n = 3 to 7 from three to six mice per group) (D) or MAFbx, MuRF1, or Gadd45a promoter firefly luciferase reporter (n = 3 to 8 from three to eight mice per group) (E). Muscles were collected at 2 days after transfection and subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay. (F and G) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) from WT mice were cotransfected with GFP, HA-tagged WT-DGKζ, or HA-tagged KD-DGKζ, and pRL and FoxO response element firefly luciferase reporter ± constitutively active (ca) FoxO3a (n = 3 to 7 from three to six mice per group) (F) or the indicated promoter firefly luciferase reporter ± caFoxO3a (n = 4 to 8 from four to eight mice per group) (G). Muscles were collected at 2 days after transfection and subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay. (H) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) from WT mice were transfected with LacZ, HA-tagged WT-DGKζ, or HA-tagged KD-DGKζ ± caFoxO3a, and collected at 7 days after transfection. Cross sections of the muscles were subjected to immunohistochemistry with antibodies against laminin (red) and LacZ (green) or HA (green) to measure CSA of the transfected and nontransfected fibers (n = 4 from three to four mice per group). The top panel shows representative images. Scale bar, 50 μm. Values were expressed as means + SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to sham within the same genotype (A to C), WT GFP (D and E), GFP (F and G), or LacZ (H); #P < 0.05 compared to WT mechanical overload (A to C), GFP + caFoxO3a (F and G), LacZ + caFoxO3a (H), two-way ANOVA (A to C), or one-way ANOVA (D to H).

DGKζ inhibits FoxO actions independently of its kinase activity

To further establish the inhibitory role of DGKζ on FoxO transcriptional activity, we overexpressed DGKζ or green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a control with FoxO reporters in the tibialis anterior muscles of WT and DGKζ KO mice. Consistent with the results from the overload experiments, overexpression of WT-DGKζ inhibited FoxO activity, although its activity was slightly enhanced in the muscles from DGKζ KO mice (Fig. 4D). We also found that the inhibitory effect of DGKζ was independent of its kinase activity because a kinase-dead mutant form of DGKζ (KD-DGKζ) inhibited FoxO activity (Fig. 4D). Similarly, both WT-DGKζ and KD-DGKζ inhibited the promoter activity of FoxO target genes (Fig. 4E). We wondered whether DGKζ could also inhibit the atrophy-promoting effect of FoxO. As previously reported (29), the overexpression of caFoxO3a induced a significant reduction in muscle fiber size and a robust increase in the activity of a FoxO3 reporter and target gene promoters (Fig. 4, F to H, and fig. S5A). However, these changes were prevented when either WT-DGKζ or KD-DGKζ was co-overexpressed with caFoxO3a (Fig. 4, F to H, and fig. S5A). Therefore, these results identify a kinase activity–independent function of DGKζ that inhibits FoxO activity and its pro-atrophic action.

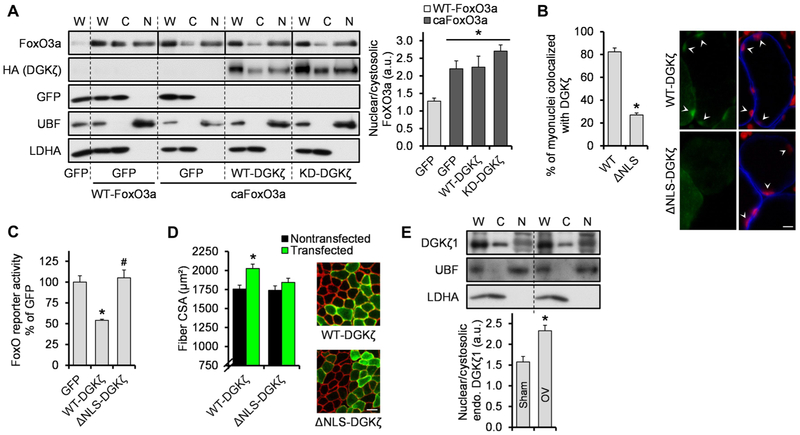

The nuclear-localization signal of DGKζ mediates the inhibition of FoxO activity and the induction of hypertrophy

FoxO regulation is achieved primarily through control of its nuclear or cytoplasmic localization. For example, FoxO is excluded from the nucleus when phosphorylated by Akt, but upon dephosphorylation, it translocates into the nucleus and becomes transcriptionally active (28). To address whether DGKζ inhibited FoxO nuclear localization, we overexpressed WT-FoxO3a or caFoxO3a (in which all three Akt phosphorylation sites were mutated) with or without WT-DGKζ or KD-DGKζ in tibialis anterior muscles. Consistent with the data obtained from cultured cells (28), our fractionation data confirmed that caFoxO3a had an enhanced nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio compared to WT-FoxO3a, but this distribution was not affected by WT-DGKζ or KD-DGKζ (Fig. 5A). On the basis of this observation and the ability of DGKζ to localize to the nucleus (Fig. 5A) (30), we hypothesized that FoxO activity was inhibited by DGKζ inside the nucleus. To test this notion, we overexpressed a form of DGKζ lacking the nuclear localization signal (NLS) (ΔNLS-DGKζ) in tibialis anterior muscles. ΔNLS-DGKζ exhibited reduced nuclear localization as expected (Fig. 5B), and it did not inhibit FoxO activity (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, fiber size measurement demonstrated that the NLS mutation prevented the hypertrophic effect of DGKζ (Fig. 5D and fig. S5B). Together, these results indicate that nuclear localization of DGKζ is critical for the inhibition of FoxO activity and the muscle hypertrophy.

Fig. 5. The NLS of DGKζ is required for the inhibition of FoxO activity and the induction of hypertrophy.

(A) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) were cotransfected with WT-FoxO3a or caFoxO3a and GFP, HA-tagged WT-DGKζ, or HA-tagged KD-DGKζ. The muscles were collected at 2 days after transfection and subjected to Western blotting to detect FoxO3a, HA (DGKζ), GFP, upstream binding factor (UBF) (nuclear marker), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) (cytosolic marker), in whole homogenates (W), cytosolic fractions (C), and nuclear fractions (N) (n = 4 from four mice per group). Solid lines distinguish images from different gels. (B) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) were transfected with FLAG-tagged WT-DGKζ or a nuclear localization signal mutant (ΔNLS)–DGKζ and collected at 2 days after transfection. Cross sections of the muscles were subjected to immunohistochemistry with PI (red) and antibodies against dystrophin (blue) and FLAG (green) to measure myonuclei that colocalized with DGKζ (n = 4 from four mice per group). The right panel shows representative images. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) were cotransfected with FoxO response element firefly luciferase reporter, pRL-SV40 Renilla luciferase, and GFP, FLAG-tagged WT-DGKζ, or FLAG-tagged ΔNLS-DGKζ. Muscles were collected at 2 days after transfection and subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay (n = 4 to 7 from four to five mice per group. (D) Tibialis anterior muscles (n) were transfected with FLAG-tagged WT-DGKζ or FLAG-tagged ΔNLS-DGKζ and collected at 7 days after transfection. Cross sections of the muscles were subjected to immunohistochemistry with antibodies against laminin (red) and FLAG (green) to measure CSA of the transfected and nontransfected fibers (n = 6 from six mice per group). The right panel shows representative images. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Mice were subjected to mechanical overload or sham surgery, and the plantaris muscles (n) were collected at 2 days after surgery and subjected to Western blotting to detect the indicated proteins in different fractions as described in (A) (n = 5 from three mice per group). a.u., arbitrary units; endo., endogenous. Values were expressed as means + SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to GFP + WT-FoxO3a (A), WT-DGKζ (B), GFP (C), nontransfected (D), or sham (E); #P < 0.05 compared to WT-DGKζ, oneway ANOVA (A and C) or Student’s t test (B, D, and E).

As mentioned above, the protein abundance of DGKζ1, the DGKζ isoform that predominates in skeletal muscle, was not robustly altered at 2 days after mechanical overload, but the presence of DGKζ substantially altered the overload-induced changes in FoxO activity and the expression of the FoxO target genes. These results, combined with the role of nuclear DGKζ, suggested that mechanical overload enhanced the specific activity of nuclear DGKζ toward FoxO inhibition and/or promoted the nuclear translocation of DGKζ. Consistent with this prediction, we found that the nuclear localization of endogenous DGKζ1 was enhanced after 2 days of mechanical overload (Fig. 5E). Therefore, in addition to the regulation of DGKζ abundance, enhanced nuclear translocation of DGKζ could be another regulatory mechanism by which DGKζ inhibits FoxO activity during mechanical overload.

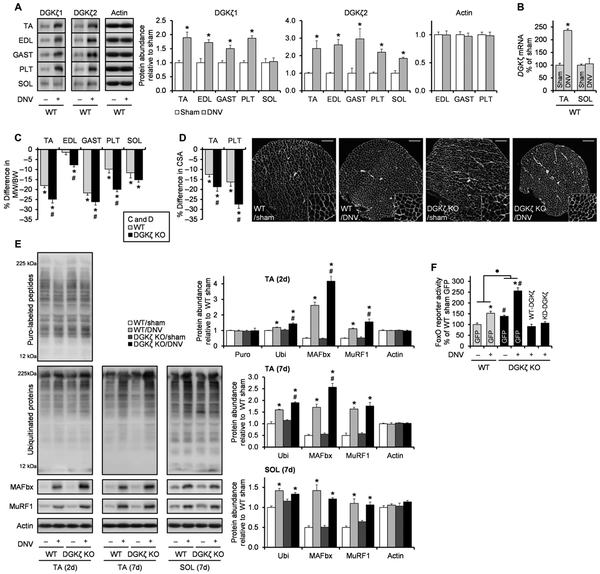

DGKζ mitigates the activation of the FoxO-UPS pathway and muscle atrophy during denervation

Because UPS-mediated protein degradation and FoxO activity are typically increased during atrophic conditions (7), we next wanted to explore whether the role of DGKζ could be extended to the prevention of muscle atrophy. In particular, we were interested in the role of DGKζ in denervation-induced muscle atrophy because denervation-induced atrophy is, at least, partially mediated by MAFbx, MuRF1, and/or FoxOs (31,32). Furthermore, we found that denervation, similar to mechanical overload, led to an increase in DGKζ mRNA and DGKζ1 protein abundance in fast-twitch muscles but not in slow-twitch soleus muscles (Fig. 6, A and B). On the basis of these findings, we envisioned that the increase in DGKζ expression could play a role in mitigating the atrophic effect of denervation. We found that the decrease in muscle mass after 7 days of denervation was exacerbated in all of the lower hindlimb muscles of DGKζ KO mice except for the soleus (Fig. 6C and table S1). Similar results were also obtained when we measured fiber CSA in tibialis anterior and plantaris muscles, confirming that DGKζ mitigated denervation-induced fiber atrophy (Fig. 6D and fig. S6). Next, we tested whether the anti-atrophic effect of DGKζ was associated with its inhibitory function on the UPS and FoxO activity. The denervation-induced activation of global ubiquitination, the increases in the abundance of MAFbx and MuRF1, and the stimulation of FoxO activity were augmented by DGKζ deficiency in tibialis anterior muscles (Fig. 6, E and F). Similar to the mechanical overload model, these effects were independent of the activation status of Akt (fig. S4B). Moreover, these effects were not observed in soleus muscles, which is consistent with the lack of an anti-atrophic effect of DGKζ KO in the soleus (Fig. 6E). Last, the augmented activity of FoxO in DGKζ KO muscles was substantially reduced when either WT-DGKζ or KD-DGKζ was re-expressed in those muscles (Fig. 6F). Therefore, our results demonstrate that DGKζ can mitigate the denervation-induced activation of the FoxO-UPS pathway and the concomitant induction of atrophy.

Fig. 6. DGKζ mitigates the activation of the FoxO-UPS pathway and muscle atrophy during denervation.

WT and DGKζ KO mice were subjected to denervation (DNV+) or sham (DNV−) surgery, and the tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), gastrocnemius (GAST), plantaris (PLT), and soleus (SOL) muscles (n) were collected at 7 days after surgery unless otherwise indicated. (A) Western blotting to detect DGKζ protein with antibodies against the C terminus of DGKζ1 (n = 4 to 6 from three to five mice per group) or the N terminus of DGKζ2 (n = 4 to 5 from three to five mice per group) in the indicated muscles. (B) qRT-PCR to measure mRNA expression of DGKζ in TA (n = 4 to 6 from three to four mice per group) and SOL (n = 5 from three to five mice per group). (C) Denervation-induced differences in the MW/BW ratio in the indicated muscles (n=9 to 13 from 9 to 13 mice per group).(D) Immunohistochemistry on cross sections with an antibody against laminin (white) to measure fiber CSA in TA (n = 5 to 6 from five to six mice per group) and PLT (n = 3 to 4 from three to four mice per group). The right panel shows representative images of the whole cross sections of the PLT muscles and their 2× magnified views. Scale bars, 200 μm. (E) Western blotting to detect the indicated proteins (n = 3 to 6 from three to six mice per group). (F) TA muscles were cotransfected with FoxO response element firefly luciferase reporter, pRL-SV40 Renilla luciferase, and GFP, HA-tagged WT-DGKζ, or HA-tagged KD-DGKζ at 5 days after denervation or sham surgery. Upon collection, the muscles were subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay (n = 3 to 7 from three to six mice per group). Values were expressed as means + SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to sham [within the same genotype in (C) to (F)], #P < 0.05 compared to WT [within the same surgery in (E) and (F)], ·P < 0.05 in the magnitude of the denervation effect between genotypes, Student’s t test (A to D and F) or two-way ANOVA (E and F).

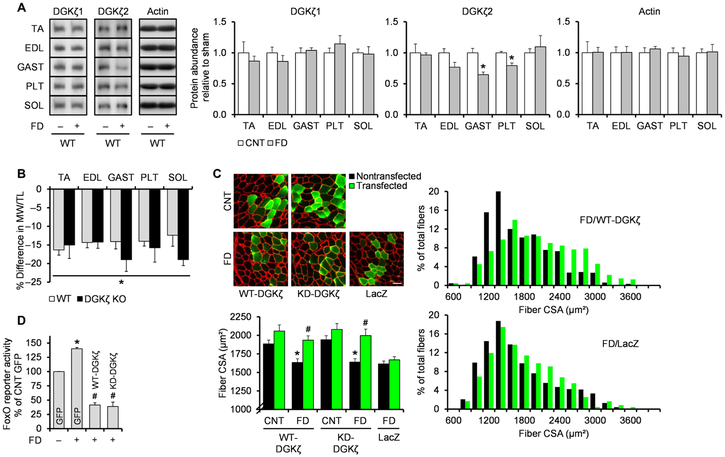

Overexpression of DGKζ inhibits food deprivation–induced muscle atrophy

On the basis of the results from the denervation experiments, we wondered whether DGKζ could also contribute to the prevention of other types of muscle atrophy and, thus, used a food deprivation model that induces muscle atrophy through a mechanism requiring FoxO activity (32). We found that the food deprivation–induced loss of muscle mass and increases in the components of the UPS were not affected by DGKζ deficiency, and similar to the soleus during denervation, these effects were associated with the lack of an increase in DGKζ1 protein abundance (Fig. 7, A and B, and fig. S7A). However, the food deprivation–induced loss of fiber size was prevented by overexpression of either WT-DGKζ or KD-DGKζ (Fig. 7C, fig. S7B, and table S1). Furthermore, the anti-atrophic effect of DGKζ during food deprivation was associated with its ability to inhibit FoxO transcriptional activity (Fig. 7D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that increasing DGKζ abundance may be a potential therapeutic strategy to combat the loss of muscle mass.

Fig. 7. Overexpression of DGKζ inhibits food deprivation–induced muscle atrophy.

(A and B) WT and DGKζ KO mice were subjected to food deprivation (FD+) or the control (FD−) condition, and the TA, EDL, GAST, PLT, and SOL muscles (n) were collected at 2 days after FD. (A) Western blotting to detect DGKζ protein with antibodies against the C terminus of DGKζ1 or the N terminus of DGKζ2 in the indicated muscles (n = 5 to 6 from three mice per group). (B) FD-induced differences in the MW/TL (tibia length) ratio in the indicated muscles (n = 5 to 6 from three mice per group). (C) TA muscles (n) from WT mice were transfected with HA-tagged WT-DGKζ, HA-tagged KD-DGKζ, or LacZ immediately before being subjected to 2 days of FD or the control (CNT) condition. Cross sections of the muscles were subjected to immunohistochemistry with antibodies against laminin (red) and LacZ (green) or HA (green) to measure CSA of the transfected and nontransfected fibers (n = 4 to 5 from three to five mice per group). The top left panel shows representative images. Scale bar, 50 μm. The right panel shows the distribution of the CSA on a histogram. (D) TA muscles (n) were cotransfected with FoxO response element firefly luciferase reporter, pRL-SV40 Renilla luciferase, and GFP, HA-tagged WT-DGKζ, or HA-tagged KD-DGKζ, immediately before being subjected to 2 days of FD or the CNT condition. Upon collection, the muscles were subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay (n = 3 from three mice per group). Values were expressed as means + SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to CNT (A and B) [within the same genotype in (B)] or CNT (C and D) [within the same transfection in (C)], #P < 0.05 compared to nontransfected within the same feeding and DNA (C) or GFP + FD (D), Student’s t test (A and B), two-way ANOVA (C), or one-way ANOVA (D).

DISCUSSION

A fundamental question for understanding the mechanisms of load-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy is how mechanical loading activates mTOR signaling and protein synthesis. Although an answer to the question is still not clear, several hypotheses have been proposed, and one that has emerged involves the activation of mTOR by a DGKζ-dependent increase in PA (14,15). However, this hypothesis has not been explored in an in vivo hypertrophic model of mechanical loading. Here, by using mechanical overload, we have obtained several lines of evidence that support this hypothesis: (i) Mechanical overload induces an increase in both PA and its precursor, DAG; (ii) mechanical overload induces an increase in the expression and membrane activity of DGKζ; and (iii) DGKζ KO impairs the mechanical overload–induced activation of mTOR signaling, protein synthesis, and muscle growth. Despite this evidence, however, we realized that the impairment of the overload-induced mTOR signaling was only partial and relatively modest compared to the changes in protein synthesis. Thus, this result suggests that, in addition to DGKζ and PA, other mechanisms are also involved in the mechanical overload–induced activation of mTOR signaling and that DGKζ KO can inhibit the overload-induced activation of protein synthesis through an mTOR-independent mechanism (fig. S8). With regard to the latter point, the mTOR-independent mechanism may be explained by our observation that DGKζ KO completely blunted the mechanical overload–induced increase in eIF3f expression, a critical component in mRNA translation (27, 33). In any case, expanding our understanding of the mechanisms responsible for the mechanical load–induced increase in mTOR signaling and protein synthesis will provide fundamental insights into how mechanical loading promotes muscle growth.

The UPS can ensure the quality of intracellular proteins in normal cells by the continual and selective degradation of misfolded and/or damaged proteins (26, 34). Furthermore, generation of these abnormal proteins could be enhanced under various stress conditions such as mechanical loading. Thus, the activation of UPS-dependent protein degradation may be considered as essential for mechanical load–induced hypertrophic remodeling. In support of this notion, many studies have reported that mechanical loading increases protein degradation, as well as key components of the UPS including muscle-specific E3 ligases and protein ubiquitination (11, 35–37). Furthermore, our data indicated that the mechanical overload–induced increase in the rate of protein degradation was UPS-dependent. However, an excessive activation of the UPS and protein degradation would eliminate the increase in the balance between the rates of protein synthesis and protein degradation that is needed for muscle growth. Thus, the rates of protein degradation after mechanical loading must be tightly regulated for skeletal muscle to efficiently accumulate intact and functional proteins. However, the mechanisms through which skeletal muscle accomplishes this regulation are not well understood. Here, we shed light on this process by identifying a role of DGKζ in preventing an excessive increase in the UPS-dependent protein degradation during mechanical overload. Furthermore, we provided evidence that this function of DGKζ involved the inhibition of FoxO transcriptional activity, which is critical for the expression of genes that regulate the UPS (12,32,38). Last, our results suggest that the inhibitory function of DGKζ on FoxO activity was likely mediated by increased protein abundance and/or nuclear translocation of DGKζ during mechanical overload. Together, our findings have unveiled a mechanism in which skeletal muscle uses DGKζ to control FoxO signaling and UPS-mediated protein degradation, thereby helping to support the hypertrophic remodeling that occurs in response to mechanical loading (fig. S8).

Similar to hypertrophic remodeling, a rapid and robust activation of the UPS frequently occurs during atrophic conditions, which inevitably contributes to the development of muscle wasting. For example, various types of muscle atrophy partially occur through a proteasome-, MAFbx-, and/or MuRF1-dependent mechanism (12, 39, 40). In addition to the UPS, the activation of FoxO also contributes to muscle wasting. For instance, Milan et al. (32) have shown that the activation of FoxO plays a critical role in denervation- and fasting-induced muscle atrophy, as well as the induction of many UPS components, such as MAFbx and MuRF1. Thus, given the importance of the UPS and/or FoxO for muscle wasting, our findings, which highlight the DGKζ-mediated inhibition of FoxO activity, the UPS, and muscle atrophy, suggest that activating or increasing the abundance of DGKζ may be a viable therapeutic strategy for the prevention of muscle wasting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and plasmid construct

Rabbit anti-p70S6k (#2708), anti-4EBP1 (#9644), anti–phospho-4EBP1 (Thr36/47; #2855), anti-eIF4G (#2469), anti-eIF4E (#2067), anti-eIF2α (#5324), anti-eEF2 (#2332), anti–pan-actin (#8456), anti–phospho-Akt (Thr308; #9275), anti-Akt (#9272), anti-FoxO3a (#2497), anti-HA (#3724), anti-GFP (#2555), and anti-LDHA (#3558) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling. Rabbit anti-phospho-p70S6k (Thr389), anti-DGKδ (sc66860), and anti-DGKε (sc98729) antibodies; mouse anti-ubiquitin (sc8017) and anti-UBF (sc13125) antibodies; goat anti-DGKζ (sc8722; C terminus–specific) and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-chicken immunoglobulin Y (IgY) (sc2431) antibodies; and normal goat IgG (sc2028) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rat anti-F4/80 antibody (#123102) was purchased from BioLegend. Rabbit anti-eIF3f antibody (#600-401-934) was purchased from Rockland Immunochemicals. Rabbit anti-DGKζ antibody (N terminus–specific) was obtained from M. Topham (University of Utah) (41). Mouse antipuromycin antibody was obtained from P. Pierre (Centre d’Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy) (42). Mouse anti-eIF4E antibody was obtained from S. Kimball (Pennsylvania State University) (43). Rabbit anti-MAFbx and mouse anti-MuRF1 antibodies were obtained from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Rabbit anti-LC3B (L7543), anti-laminin (L9393), anti–laminin-2 (L0663), and anti-FLAG (F7425) antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse IgG1 anti–type 2a MHC (clone SC-71), mouse IgM anti–type 2b MHC (clone BF-F3), and mouse IgM anti–type 2x MHC (clone 6H1) antibodies were purchased from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. Mouse IgG1 antidystrophin antibody (NCL-DYS2; Novocastra) was purchased from Leica Biosystems. Chicken IgY anti–β-galacto-sidase (LacZ; ab9361) was purchased from Abcam. Rat anti-HA IgG1 antibody (#11867431001) was purchased from Roche Applied Science. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (PI-1000), anti-mouse IgG (PI-2000), and anti-goat IgG (PI-9500) anti-bodies were purchased from Vector Laboratories. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG 2a (#115-035-206), Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 (#115-545-205) and anti-rat IgG (#112-545-167), amino-methylcoumarin acetate–conjugated anti-mouse IgM (#115-155-075), and Dylight 594–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (#711-515-152) antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. Alexa Fluor 350–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (A-11046) and anti-rat IgG (A-21093), and Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (A-11008) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen.

pEGFP-C3 (GFP) was purchased from Clontech. pCMVβ (LacZ) was purchased from Marker Gene Technologies Inc. pHA3-DGKζ (WT-DGKζ, pcDNA1-FLAG-DGKζ (WT-DGKζ, and pcDNA1-FLAG-DGKζ with K/R → A in the MARCK-PDS-homology domain of DGKζ2 (aa256-273) (ΔNLS-DGKζ (30) were obtained from M. Topham (University of Utah). KD-DGKζ was generated from pHA3-DGKζ as previously described (15). pECE-FoxO3a (WT-FoxO3a) and pECE-FoxO3a with three Akt phosphorylation site mutations (T32A, S253A, and S315A) (caFoxO3a) were obtained from P. Coffer (University Medical Center Utrecht). pCMV2-FLAG-IKK-2 with two phosphomimetic mutations in the kinase activation loop (S177E and S181E) (caIKKβ; #11105) was purchased from Addgene. pGL3-FoxO response element firefly luciferase was obtained from A. Toker (Harvard University). pGL3–NF-κB response element firefly luciferase was obtained from S. Kandarian (Boston University). pGL3-MAFbx promoter firefly luciferase and pGL2-MuRF1 promoter firefly luciferase were obtained from M. Sandri (University of Padova). pGL-Gadd45α promoter firefly luciferase was obtained from T. Maekawa (RIKEN Tsukuba Institute). pRL-SV40 Renilla luciferase was purchased from Promega. All plasmid DNA was grown in DH5α Escherichia coli, purified with an EndoFree plasmid kit (Qiagen), and resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Animals and sampling

Female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250 to 270 g were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc. and used for mechanical overload studies. DGKζ−/− C57BL/6 mice were stably obtained by crossing heterozygous female with homozygous KO male [a gift from X.-P. Zhong, Duke University (44)]. After weaning, male offspring were used for mechanical overload, maximal-intensity contractions, and food deprivation studies, and female offspring were used for denervation and other studies. WT C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were 8 to 10 weeks of age at the initiation of the studies. All animals were housed in a room maintained at 25°C with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle and received food and water ad libitum except in the food deprivation study. Before all surgical procedures, animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (body weight, 100 mg/kg) and xylazine (body weight, 10 mg/kg). At the end of the experimental procedures, muscles were collected and either immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for nonhistochemical analyses or submerged in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek) at resting length and frozen in liquid nitrogen–chilled isopentane for histochemical analyses. Mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia. All animal methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Wisconsin-Madison under protocol #V01324.

Mechanical overload, denervation, maximal-intensity contractions, and food deprivation

Bilateral mechanical overload of the plantaris muscle was induced by synergist ablation surgery that involved the removal of the soleus and distal one-third of the gastrocnemius muscles in both legs, leaving the plantaris as the sole plantar flexor muscle. In some cases, bilateral mechanical overload of the extensor digitorum longus muscle was also induced by the removal of distal one-third of tibialis anterior muscle in both legs. Unilateral denervation of the hindlimb muscles was achieved by a small excision (0.5 cm) of the sciatic nerve in the right leg. Mice in the control group received a sham surgery that involved only an incision in the skin where the synergist ablation or denervation surgery would have occurred. After the surgeries, the skin incisions were closed with a 5-0 polysorb suture (SL-1614-G; Covidien). Maximal-intensity contractions in the right tibialis anterior muscle were elicited by stimulating the sciatic nerve with an SD9E grass stimulator (Grass Instruments) at 100 Hz, 3 to 7 V pulse, for 10 sets of six contractions. Each contraction lasted 3 s, followed by a 10-s rest period, and a 1-min rest period was provided between each set. The left unstimulated tibialis anterior muscle was used as a control. For food deprivation, mice had food withdrawn for 48 hours, with ad libitum access to water.

Skeletal muscle transfection

Mouse tibialis anterior or plantaris muscles were transfected by electroporation as previously described (45). Briefly, a plasmid DNA solution was injected into proximal and distal ends of the muscle belly with a 27-gauge needle. After the injections, two stainless steel pin electrodes (1-cm gap) connected to an ECM 830 electroporation unit (BTX/Harvard Apparatus) were laid on top of the proximal and distal myotendinous junctions of the tibialis anterior or gastrocnemius (for plantaris). Then, eight 20-ms square-wave electric pulses were delivered onto the muscle at a frequency of 1 Hz with a field strength of 160 V/cm. In some cases, the electroporation procedure was preceded by mechanical overload, denervation, or food deprivation. After electroporation, the incisions were closed with a 5-0 polysorb suture.

Sample preparation and fractionation

To assess DGK activity, frozen muscles were homogenized with a Polytron in ice-cold buffer A [20 mM tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and leupeptin, pepstatin, aprotinin, and soybean trypsin inhibitor (20 μg/ml each)], and the homogenates were precleared by centrifugation at 1000g for 10 min (4°C). The precleared supernatants (whole homogenate) were further centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 hour (4°C) to separate the soluble supernatants (cytosolic fraction) and insoluble pellets (crude membrane fraction) as demonstrated previously (15). The membrane pellets were washed once and resuspended in the ice-cold buffer A.

For Western blot analysis (and immunoprecipitation), frozen muscles were homogenized with a Polytron in ice-cold buffer B [40 mM tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 25 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, and leupeptin (10 μg/ml)], and the whole homogenate was subjected to further analysis. When nuclear fractionation was needed, frozen muscles were homogenized with a Polytron in ice-cold buffer C [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, and leupeptin (10 μg/ml)], and the homogenates (whole homogenate) were centrifuged at 900g for 5 min (4°C) as previously described (46). The resulting supernatants (cytoplasmic fraction) were further cleared from the residual nuclei by centrifugation at 900g three times, and the pellets (crude nuclear fraction) were washed three times with the ice-cold buffer C. The nuclear pellets were then resuspended in the ice-cold buffer C containing about 600 mM NaCl and incubated for 1 hour (4°C) to lyse the nuclei. The resuspended pellets were centrifuged at 22,000g for 15 min (4°C) to obtain nuclear protein-containing supernatants. The protein concentration in each homogenate was determined with the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) and used to control the loading amounts of whole, cytosolic, or membrane protein in the DGK activity assay or whole, cytoplasmic, or nuclear protein in the Western blot analyses.

DGK activity assay

DGK activity was measured in vitro by the standard octyl glucoside (OG)/ phosphatidylserine (PS)–mixed micelle assay. Briefly, OG/PS-mixed micelles were prepared by resuspending dried DAG (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol) and PS (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine) in 5× OG buffer (275 mM OG and 1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid). The reaction was then initiated by combining 10 μl of each diluted sample or protein G agarose beads with 20 μl of the OG/PS-mixed micelles and 70 μl of reaction mixture, which yielded a final concentration of {55 mM OG, 0.25 mM DAG [0.87 mole percent (mol %) in micelles], 1 mM PS, 50 mM imidazole (pH 6.6), 50 mM NaCl, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM diethylenetriamine-pentaacetic acid, 1 mM DTT, 500 μM adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), and 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP}. In some cases, R59949 (12 mol % in micelles) was preincubated in the mixture of sample and OG/PS-mixed micelles for 10 min before the start of the reaction. After a 30-min incubation at 25°C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.45 ml of chloroform/methanol 1:2 (v/v) and 0.15 ml of 1% perchloric acid. [γ-32P]PA was then extracted and separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with a solvent system consisting of ethyl acetate/isooctane/acetic acid/deionized water (diH2O) 11:5:2:10 (v/v) as previously described (15). The amount of [γ-32P]PA was visualized and quantified with a Storm PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

To immunoprecipitate DGKζ and subsequently assess DGK activity, equal amounts of protein from each whole homogenate that was prepared in ice-cold buffer A or membrane fractions that were derived from equal amounts of whole homogenate protein were incubated with goat anti-DGKζ antibody (1:13) (4 hours, 4°C), followed by 20 μl of protein G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (overnight, 4°C). After incubation, DGKζ-depleted supernatants were collected, and the beads were washed three times with fresh ice-cold buffer A. For immunoprecipitation of eIF4E and subsequent Western blotting, whole homogenates prepared in ice-cold buffer B were precleared by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min (4°C). Then, equal amounts of protein from each sample were incubated with mouse anti-eIF4E antibody (1:10) (2 hours, 4°C), followed by 20 μl of protein A agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (2 hours, 4°C) that were preblocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (1 hour, 4°C). After the incubations, the beads were washed four times with fresh ice-cold buffer B. Western blot analyses were performed with equal amounts of protein from each sample as previously described (15). Once the appropriate image was captured, the membranes were stained with Coomassie Blue to ensure equal loading and transfer of proteins throughout all lanes (47). Actin blots were also used to verify the specificity of the changes in the abundance of the proteins of interest.

Measurements of protein synthesis and protein degradation

The rate of protein synthesis was measured in vivo with the surface sensing of translation technique as previously described (48). Briefly, mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of puromycin (body weight, 0.04 μmol/g; EMD Millipore) dissolved in 200 μl of PBS, and exactly 30 min after injection, muscles were collected and subjected to Western blotting to detect puromycin-labeled peptides.

The rate of protein degradation was measured ex vivo by monitoring the rate of tyrosine release according to previously described methods with minor modifications (15, 49). Briefly, plantaris muscles were placed in an organ culture system, which consisted of a refined myograph apparatus (Kent Scientific) and an organ culture bath, and incubated at 37°C in Krebs-Henseleit buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, and 5 mM Hepes) supplemented with 1× minimum essential medium amino acid mixture (Invitrogen), 25 mM glucose, and continuous 95% O2 and 5% CO2 gassing. The medium was refreshed every 10 min during the initial 30-min preincubation period and then remained unchanged for 2 hours in the presence of 0.5 mM cyclohexamide (Acros Organics) to allow tyrosine accumulation in the medium. In some cases, the activity of the proteasome was inhibited by incubating the muscles with 30 μM MG132 (Cayman Chemical) during the last 10 min of the preincubation period and throughout the 2-hour release period. After collection, the medium was mixed with an equal volume of nitrosonaphthol/nitric acid reagent 50:50 (v/v) and incubated at 55°C for 30 min. Ethylene dichloride was then added to the mixture and centrifuged briefly, and a fluorescent tyrosine derivative in the upper aqueous phase was quantified by FLUOstar Optima fluorimeter (BMG Labtech) with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm, using 0.3 to 10 μM tyrosine standards.

Immunohistochemistry

Cross sections (10 μm thick) from the midbelly of the muscles frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound were obtained with a cryostat and fixed in acetone for 10 min at −30°C. The sections were warmed to room temperature (RT) for 5 min and rehydrated with PBS for 15 min. The sections were then incubated in solution A (PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100) for 20 min and probed with the indicated primary antibodies (dissolved in solution A) for 1 hour at RT. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with the appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (dissolved in solution A) for 1 hour at RT. When nuclei staining was needed, the sections were subsequently incubated with propidium iodine (20 μg/ml) for 5 min. After a final wash with PBS, fluorescent signals from each secondary antibody or propidium iodine were captured with a DS-QiMc camera on an 80i epifluorescence microscope (both from Nikon) at RT, and the resulting monochrome images were merged with NIS-Elements D image analysis software (Nikon). Investigators that were blinded to the sample identification then used NIS-Elements D to measure the total fiber number per muscle cross section, average fiber CSA, myonuclei per fiber, macrophage density, and myonuclear localization.

Luciferase activity assay

Muscles transfected with plasmid DNA encoding a luciferase reporter were homogenized with a Polytron in passive lysis buffer (Promega), and firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured by a FLUOstar Optima luminometer using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity in the same sample.

In vivo measurements of [DAG] and [PA]

Total lipids were extracted from a 160-mg portion of powdered muscle as previously described (50). The samples were then separated by TLC with a solvent system consisting of hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid 50:50:1 (v/v) for DAG or ethyl acetate/isooctane/acetic acid/diH2O 11:5:2:10 (v/v) for PA. The amount of lipids was visualized by 2 hours of staining in 30% methanol, 0.03% (w/v) Coomassie Blue R250, and 100 mM NaCl, followed by 5 min of destaining in 30% methanol and 100 mM NaCl, and then quantified by transmission densitometry using 1 to 30 μg of DAG or 0.5 to 5.0 μg of PA standards.

Gene expression analysis

Frozen muscles were homogenized with a ribonuclease-free pestle in ice-cold TRIzol (Ambion), and total RNA was isolated with a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and integrity of RNA samples were checked by the ratio of A260/A280 absorbance and of 28S/18S ribosomal RNA, respectively. cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 μg of total RNA by using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) and analyzed for gene expression by quantitative PCR using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences used were as follows: 5′-CAATGCATTAAGCAGCTGGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGTGAACTTCTGCTGGAAGC-3′ (reverse) for DGKζ, 5′ -CTTTCAACAGACTGGACTTCTCGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGCTCCAACAGCCTTACTA CGT-3′ (reverse) for MAFbx, 5′-GAGAACCTGGAGAAGC AGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCGCGG TTGGTCCAGTAG-3′ (reverse) for MuRF1, 5′ -GAAAGTCGCTACATGGATCAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAACTTCAGTGCAATTTGGTTC-3′ (reverse) for Gadd45a, and 5′-CCAGCCTCGTCCCGTAGAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATGGCAACAATCTCCACTTTGC-3′ (reverse) for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean (+SEM) from at least three independent experiments. Sample sizes were determined on the basis of preliminary data and previous publications. Animals were randomly allocated to the different experimental groups except when they were used for CSA analyses that required a similar average body weight across the groups. Animals that showed any sign of sickness according to pre-established criteria were excluded from experiments. A sample value that deviated more than three times from the mean in a given group was also excluded as an outlier. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined by an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test for single comparison or one- or two-way ANOVA followed by planned comparisons or Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test for multiple comparisons. In cases where sample number represents pairs of right and left muscles from the same animals, a repeated-measures ANOVA was used to validate the statistical significance. Tests were performed upon verification of the test assumptions. The variation was similar between the test groups. All statistical analyses were performed using Excel and SigmaStat.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Mechanical overload activates DAG-PA-mTOR signaling and increases DGKζ activity.

Fig. S2. DGKζ preserves type 2b fiber size during mechanical overload.

Fig. S3. The effects of DGKζ KO on mTOR signaling events and FoxO target gene expression after the onset of mechanical overload.

Fig. S4. The effects of DGKζ KO on the phosphorylation of Akt.

Fig. S5. The effects of DGKζ overexpression on the distribution of fiber size under various conditions.

Fig. S6. The effects of denervation on the distribution of fiber size in WT and DGKζ KO muscles.

Fig. S7. The effects of DGKζ KO on the activation of the UPS during food deprivation.

Fig. S8. A proposed mechanism through which DGKζ promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy in response to mechanical overload.

Table S1. Muscle weight, body weight, and tibia length.

Acknowledgments:

We thank X.-P. Zhong (Duke University, Durham, NC), M. Topham (University of Utah, UT), S. Kimball (Pennsylvania State University, PA), P. Pierre (Centre d′Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy, France), P. Coffer (University Medical Center Utrecht, Netherlands), A. Toker (Harvard University, MA), S. Kandarian (Boston University, MA), M. Sandri (University of Padova, Italy), and D. Allen (University of Colorado, CO) for providing resources. Special thanks are extended to Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Tarrytown, NY) for providing the anti-MAFbx and anti-MuRF1 antibodies.

Funding: This work was supported by an NIH grant (R01 AR057347 to T.A.H.). E.-J.K. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (grant no. PDF17481306) from S. G. Komen.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/11/530/eaao6847/DC1

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The MAFbx and MuRF1 antibodies require a material transfer agreement from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Evans WJ, Skeletal muscle loss: Cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 1123S–1127S (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg AL, Etlinger JD, Goldspink DF, Jablecki C, Mechanism of work-induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle. Med. Sci. Sports 7, 185–198 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izumiya Y, Hopkins T, Morris C, Sato K, Zeng L, Viereck J, Hamilton JA, Ouchi N, LeBrasseur NK, Walsh K, Fast/glycolytic muscle fiber growth reduces fat mass and improves metabolic parameters in obese mice. Cell Metab 7, 159–172 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srikanthan P, Karlamangla AS, Relative muscle mass is inversely associated with insulin resistance and prediabetes. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 2898–2903 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srikanthan P, Karlamangla AS, Muscle mass index as a predictor of longevity in older adults. Am. J. Med. 127, 547–553 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X, Wang JL, Lu J, Song Y, Kwak KS, Jiao Q, Rosenfeld R, Chen Q, Boone T, Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Goldberg AL, Han HQ, Reversal of cancer cachexia and muscle wasting by ActRIIB antagonism leads to prolonged survival. Cell 142, 531–543 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiaffino S, Dyar KA, Ciciliot S, Blaauw B, Sandri M, Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS J 280, 4294–4314 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haghighat A, Mader S, Pause A, Sonenberg N, Repression of cap-dependent translation by 4E-binding protein 1: Competition with p220 for binding to eukaryotic initiation factor-4E. EMBO J. 14, 5701–5709 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Kozlowski MT, Sugimoto T, Andrabi K, Weng Q-P, Kasuga M, Nishimoto I, Avruch J, Regulation of eIF-4E BP1 phosphorylation by mTOR. J. Biol. Chem 272, 26457–26463 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raught B, Peiretti F, Gingras A-C, Livingstone M, Shahbazian D, Mayeur GL, Polakiewicz RD, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Phosphorylation of eucaryotic translation initiation factor 4B Ser422 is modulated by S6 kinases. EMBO J. 23, 1761–1769 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murton AJ, Constantin D, Greenhaff PL, The involvement of the ubiquitin proteasome system in human skeletal muscle remodelling and atrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782, 730–743 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodine SC, Baehr LM, Skeletal muscle atrophy and the E3 ubiquitin ligases MuRF1 and MAFbx/atrogin-1. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 307, E469–E484 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hornberger TA, Mechanotransduction and the regulation of mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 43, 1267–1276 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.You JS, Frey JW, Hornberger TA, Mechanical stimulation induces mTOR signaling via an ERK-independent mechanism: Implications for a direct activation of mTOR by phosphatidic acid. PLOS ONE 7, e47258 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.You J-S, Lincoln HC, Kim C-R, Frey JW, Goodman CA, Zhong X-P, Hornberger TA, The role of diacylglycerol kinase ζ and phosphatidic acid in the mechanical activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem 289, 1551–1563 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon M-S, Sun Y, Arauz E, Jiang Y, Chen J, Phosphatidic acid activates mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) kinase by displacing FK506 binding protein 38 (FKBP38) and exerting an allosteric effect. J. Biol. Chem 286, 29568–29574 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mobley CB, Hornberger TA, Fox CD, Healy JC, Ferguson BS, Lowery RP, McNally RM, Lockwood CM, Stout JR, Kavazis AN, Wilson JM, Roberts MD, Effects of oral phosphatidic acid feeding with or without whey protein on muscle protein synthesis and anabolic signaling in rodent skeletal muscle. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr 12, 32 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thalacker-Mercer A, Stec M, Cui X, Cross J, Windham S, Bamman M, Cluster analysis reveals differential transcript profiles associated with resistance training-induced human skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Physiol. Genomics 45, 499–507 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Blitterswijk WJ, Houssa B, Properties and functions of diacylglycerol kinases. Cell. Signal 12, 595–605 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y, Sakane F, Kanoh H, Walsh JP, Selectivity of the diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor 3-[2-(4-[bis-(4-fluorophenyl)methylene]-1-piperidinyl)ethyl]-2,3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1 H) quinazolinone (R59949) among diacylglycerol kinase subtypes. Biochem. Pharmacol 59, 763–772 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldanzi G, Alchera E, Imarisio C, Gaggianesi M, Dal Ponte C, Nitti M, Domenicotti C, van Blitterswijk WJ, Albano E, Graziani A, Carini R, Negative regulation of diacylglycerol kinase θ mediates adenosine-dependent hepatocyte preconditioning. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1059–1068 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman CA, Frey JW, Mabrey DM, Jacobs BL, Lincoln HC, You J-S, Hornberger TA, The role of skeletal muscle mTOR in the regulation of mechanical load-induced growth. J. Physiol 589, 5485–5501 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman CA, Kotecki JA, Jacobs BL, Hornberger TA, Muscle fiber type-dependent differences in the regulation of protein synthesis. PLOS ONE 7, e37890 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiPasquale DM, Cheng M, Billich W, Huang SA, van Rooijen N, Hornberger TA, Koh TJ, Urokinase-type plasminogen activator and macrophages are required for skeletal muscle hypertrophy in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 293, C1278–C1285 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egner IM, Bruusgaard JC, Gundersen K, Satellite cell depletion prevents fiber hypertrophy in skeletal muscle. Development 143, 2898–2906 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lecker SH, Goldberg AL, Mitch WE, Protein degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in normal and disease states. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 17, 1807–1819 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagirand-Cantaloube J, Offner N, Csibi A, Leibovitch MP, Batonnet-Pichon S, Tintignac LA, Segura CT, Leibovitch SA, The initiation factor eIF3-f is a major target for atrogin1/MAFbx function in skeletal muscle atrophy. EMBO J 27, 1266–1276 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME, Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96, 857–868 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandri M, Lin J, Handschin C, Yang W, Arany ZP, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL, Spiegelman BM, PGC-1α protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16260–16265 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topham MK, Bunting M, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Blackshear PJ, Prescott SM, Protein kinase C regulates the nuclear localization of diacylglycerol kinase-ζ. Nature 394, 697–700 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK-M, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro J, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan Z-Q, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ, Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294, 1704–1708 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milan G, Romanello V, Pescatore F, Armani A, Paik J-H, Frasson L, Seydel A, Zhao J, Abraham R, Goldberg AL, Blaauw B, DePinho RA, Sandri M, Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat. Commun 6, 6670 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez AMJ, Csibi A, Raibon A, Docquier A, Lagirand-Cantaloube J, Leibovitch M-P, Leibovitch SA, Bernardi H, eIF3f: A central regulator of the antagonism atrophy/hypertrophy in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 45, 2158–2162 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg AL, Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature 426, 895–899 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar V, Atherton P, Smith K, Rennie MJ, Human muscle protein synthesis and breakdown during and after exercise. J. Appl. Physiol (1985) 106, 2026–2039 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyazaki M, McCarthy JJ, Fedele MJ, Esser KA, Early activation of mTORC1 signalling in response to mechanical overload is independent of phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signalling. J. Physiol 589, 1831–1846 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baehr LM, Tunzi M, Bodine SC, Muscle hypertrophy is associated with increases in proteasome activity that is independent of MuRF1 and MAFbx expression. Front Physiol 5, 69 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brocca L, Toniolo L, Reggiani C, Bottinelli R, Sandri M, Pellegrino MA, FoxO-dependent atrogenes vary among catabolic conditions and play a key role in muscle atrophy induced by hindlimb suspension. J. Physiol 595, 1143–1158 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beehler BC, Sleph PG, Benmassaoud L, Grover GJ, Reduction of skeletal muscle atrophy by a proteasome inhibitor in a rat model of denervation. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 231, 335–341 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krawiec BJ, Frost RA, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Lang CH, Hindlimb casting decreases muscle mass in part by proteasome-dependent proteolysis but independent of protein synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 289, E969–E980 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abramovici H, Hogan AB, Obagi C, Topham MK, Gee SH, Diacylglycerol kinase-ζ localization in skeletal muscle is regulated by phosphorylation and interaction with syntrophins. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4499–4511 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P, SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat. Methods 6, 275–277 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimball SR, Jurasinski CV, Lawrence JC Jr., Jefferson LS, Insulin stimulates protein synthesis in skeletal muscle by enhancing the association of eIF-4E and eIF-4G. Am. J. Physiol. 272, C754–C759 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhong X-P, Hainey EA, Olenchock BA, Jordan MS, Maltzman JS, Nichols KE, Shen H Koretzky GA, Enhanced T cell responses due to diacylglycerol kinase ζ deficiency. Nat. Immunol. 4, 882–890 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.You J-S, Anderson GB, Dooley MS, Hornberger TA, The role of mTOR signaling in the regulation of protein synthesis and muscle mass during immobilization. DIs. Model. Mech 8, 1059–1069 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothermel B, Vega RB, Yang J, Wu H, Bassel-Duby R, Williams RS, A protein encoded within the Down syndrome critical region is enriched in striated muscles and inhibits calcineurin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8719–8725 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welinder C, Ekblad L, Coomassie staining as loading control in Western blot analysis. J. Proteome Res 10, 1416–1419 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodman CA, Mabrey DM, Frey JW, Miu MH, Schmidt EK, Pierre P, Hornberger TA, Novel insights into the regulation of skeletal muscle protein synthesis as revealed by a new nonradioactive in vivo technique. FASEB J. 25, 1028–1039 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waalkes TP, Udenfriend S, A fluorometric method for the estimation of tyrosine in plasma and tissues. J. Lab. Clin. Med 50, 733–736 (1957). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Neil TK, Duffy LR, Frey JW, Hornberger TA, The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phosphatidic acid in the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin following eccentric contractions. J. Physiol 587, 3691–3701 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Mechanical overload activates DAG-PA-mTOR signaling and increases DGKζ activity.

Fig. S2. DGKζ preserves type 2b fiber size during mechanical overload.

Fig. S3. The effects of DGKζ KO on mTOR signaling events and FoxO target gene expression after the onset of mechanical overload.

Fig. S4. The effects of DGKζ KO on the phosphorylation of Akt.

Fig. S5. The effects of DGKζ overexpression on the distribution of fiber size under various conditions.

Fig. S6. The effects of denervation on the distribution of fiber size in WT and DGKζ KO muscles.

Fig. S7. The effects of DGKζ KO on the activation of the UPS during food deprivation.

Fig. S8. A proposed mechanism through which DGKζ promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy in response to mechanical overload.

Table S1. Muscle weight, body weight, and tibia length.