Abstract

Background:

Classifying individuals based on magnetic resonance data is an important task in neuroscience. Existing brain network based methods to classify subjects analyze data from a cross-sectional study and these methods cannot classify subjects based on longitudinal data. We propose a network-based predictive modeling method to classify subjects based on longitudinal magnetic resonance data.

New method:

Our method generates a dynamic Bayesian network model for each group which represents complex spatiotemporal interactions among brain regions, and then calculates a score representing that subject’s deviation from expected network patterns. This network-derived score, along with other candidate predictors, are used to construct predictive models.

Results:

We validated the proposed method based on simulated data and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. For the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study, we built a predictive model based on the baseline biomarker characterizing the baseline state and the network-based score which was constructed based on the state transition probability matrix. We found this combined model achieved 0.86 accuracy, 0.85 sensitivity, and 0.87 specificity.

Comparison with existing methods: For the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study, the model based on the baseline biomarkers achieved 0.77 accuracy. The accuracy of our model is significantly better than the model based on the baseline biomarkers (p-value = 0.002).

Conclusions:

We have presented a method to classify subjects based on structural dynamic network model based scores. This method is of great importance to distinguish subjects based on structural network dynamics and the understanding of the network architecture of brain processes and disorders.

Keywords: brain network, predictive modeling, magnetic resonance imaging, Alzheimer’s disease, dynamic Bayesian network

1. Introduction

Studying brain networks has the potential to greatly advance our understanding of the neuropathology of many neurological and psychiatric disorders. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is routinely employed to study brain networks at macroscale resolution, because of its widespread availability and safety (NIH 2013). T1-weighted structural MR imaging (MRI) is an important imaging tool used to infer brain structural networks. T1-MRI data are routinely acquired for clinical purposes, and therefore are readily available to study. Researchers can analyze T1-MRI to estimate brain morphological features such as global and regional volumes, or cortical thickness. Therefore, T1-MRI is widely used to study brain networks in a number of developmental and pathological processes including brain development(Zielinski, Gennatas et al. 2010), healthy aging(Montembeault, Joubert et al. 2012), Alzheimer’s disease (AD)(Reid and Evans 2013), schizophrenia(Mitelman, Brickman et al. 2005), autism(Zielinski, Anderson et al. 2012; Sato, Hoexter et al. 2013), and stroke(Buch, Modir Shanechi et al. 2012).

Network inference refers to the process of reconstructing brain networks from MRI data. Currently, one of the most widely used network inference methods for T1-MRI data is structural co-variance modeling, which centers on detecting structural co-variance associations(Alexander-Bloch, Giedd et al. 2013). The between-subject variation in a morphological feature of a brain region is often associated with that in other brain regions. Such associations are referred to as structural co-variance(Alexander-Bloch, Giedd et al. 2013). However, most existing network inference methods are designed to analyze data from a cross-sectional study. The network model generated by such a method provides only a static view of the interactions among brain regions.

We have proposed a network inference method for longitudinal T1-MRI data called structural dynamic network analysis (SDNA)(Chen, Resnick et al. 2012). SDNA uses a dynamic Bayesian network (DBN) to represent evolving inter-regional dependencies. The major advantage of SDNA is that it can capture complicated interactions among temporal processes.

Making predictions about individuals is a critical task in neuroscience and translational medicine(Berner 2006; Poldrack, Halchenko et al. 2009). However, SDNA does not have the capability for predictive modeling. Therefore, in this study, we propose a method, called predictive structural dynamic network analysis (PSDNA), which uses the network generated by SDNA for predictive modeling. PSDNA is based on the generalized likelihood ratio (GLR) principle (Kay 1998) and DBN modeling. It can construct a network-based classifier based on training data. For a new subject, PSDNA calculates a score that represents that subject’s deviation from expected network patterns. This method is of great importance to the understanding of the network architecture of brain processes and disorders.

2. Background

PSDNA is based on DBN modeling. A Bayesian network (Pearl 1988; Koller and Friedman 2009) is a compact representation of a joint probability distribution among a set of variables. In a Bayesian network, the joint probability is represented in factorized form which encodes a set of conditional independences. A DBN (Koller and Friedman 2009; Chen, Resnick et al. 2012) is an extension of a Bayesian network that can model temporal patterns. Consider a discrete-time stochastic process, in which a random vector yt = [y1,t, …, yn,t]T follows the distribution P(yt), where t indexes the time point, and yi,t is the ith variable at time t. A DBN is defined as a pair, (B1, B→), where B1 is a regular Bayesian network that defines the initial probability distribution P(y1), and B→ defines the transition probability P(yt+1 | yt,). B→ is a two-slice temporal Bayesian network. The variables in the first slice of a two-slice temporal Bayesian network do not have parameters associated with them, while those in the second slice have associated conditional probability tables. In B→, we assume that there are no inter-slice edges.

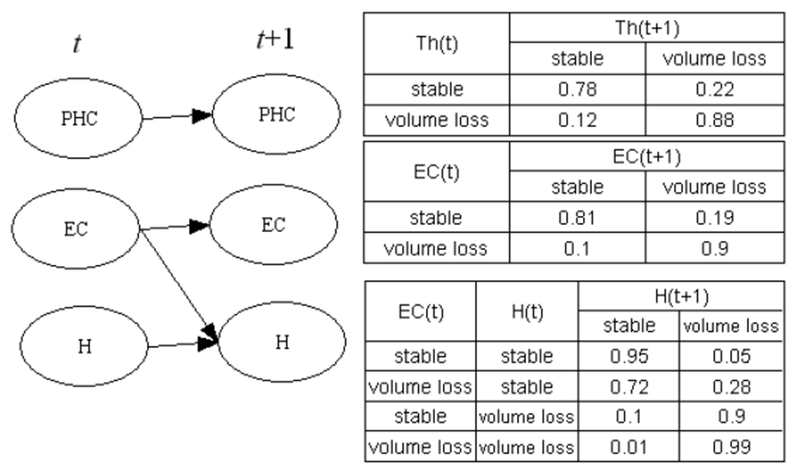

B→ describes system dynamics, and is a crucial part of a DBN model. The interactions among trajectories of different brain regions are encoded in the structure of B→. The strength of these interactions can be inferred based on conditional probability tables of B→Figure 1 depicts a hypothetical DBN which models brain volume changes in patients with AD. This DBN involves three brain regions: the thalamus (Th), entorhinal cortex (EC), and hippocampus (H). The conditional probability tables are in the right part of Figure 1. Based on the conditional probability table of the hippocampus, when the entorhinal cortex is in the state of “volume loss” at time t (ECt = volume loss), the probability of the hippocampus undergoing volume loss at time t+1 is 0.9. This is significantly higher than when ECt = stable, regardless of whether the state of hippocampus at time t. This represents a case in which morphological changes of the entorhinal cortex affect those of the hippocampus.

Figure 1.

An example of a DBN modeling interactions among temporal processes

DBNs for longitudinal MR data provide valuable information about the structural interactions among brain regions and their regulation and coordination that cannot be constructed using cross-sectional MR data. The network inference algorithm based on cross-sectional data cannot describe network dynamics. In contrast, the transition probability matrix, B→, along with the initial probability distribution, is a powerful mathematical model for trajectory analysis.

3. Methods

PSDNA centers on discriminating subjects at the individual level based on network models. Let g be a binary variable representing a subject’s group membership; g can be either a demographic (such as young or old) or a clinical variable (such as disease or control). Our goal is to build a decision-support system to generate a score that is predictive of g.

3.1. Data preprocessing

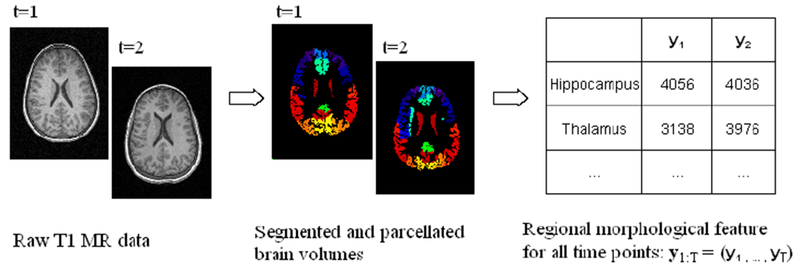

Data preprocessing includes image preprocessing and feature extraction (Figure 2). In order to construct brain networks, we must define nodes (neural components) and edges among these nodes. An atlas based approach for network modeling is widely used in brain network research because of its computational tractability and reproducibility.(Bullmore and Bassett 2011) Therefore, we use a brain atlas to define nodes. During the feature-extraction phase, we extract morphological features, such as volume or thickness, for each structure defined in a brain atlas, and repeat this process for each time point. We can use a pipeline based on Freesurfer(Fischl 2012), FSL(Jenkinson, Beckmann et al. 2012), or SPM(SPM 2014) for brain parcellation and morphological feature extraction in order to obtain regional morphological features.

Figure 2.

Image preprocessing

After obtaining regional morphological features, we calculate the change rate (Chen, Resnick et al. 2012) to quantify the rate of change for structure k at time t. The change rate is defined as

| (1) |

where TI(t, t−1) is the time interval between time t and t−1, Ω(t, k) is the measurement of brain structure k at time t. If r(t, k) is less than a threshold, the structure k manifests volume loss at time t we set its state as ‘1’ (volume loss); otherwise, we set its state as ‘0’ (normal).

Let P and T denote the number of the brain structures and the number of time points respectively. For each subject, xt is a P-dimensional vector representing the regional morphological feature of all brain structures at time t; and the sequence x1:T =(x1, …, xT) represents the regional morphological features for all time points. Then we can calculate the change rate yt which is a P-dimensional vector representing the rate of change in regional morphological measurement of all brain structures at time t. y1:T =(y1, …, yT) is the rate of change for all time points. Let y1:T (k) be the time series of subject k. n is the total number of subjects in the study. The collection of y1:T for all subjects, denoted by Y=[y1:T (1), …, y1:T (n)], is the input to the next step.

3.2. Network inference

The goal of network inference is to construct a DBN from Y. We use the method described in (Chen, Resnick et al. 2012) for network inference.

For a study involving P brain regions, B→ includes 2P variables: y(t) and y(t+1) are variables at time t and t+1. y(t) and y(t+1) are nodes in the first slice and second slice respectively of a two-slice temporal Bayesian network. Determining the structure of B→ is equivalent to inferring the parent set of y(t+1). This parent set is a subset of y(t). We use the BDe score (Cooper and Herskovits 1992; Heckerman and Chickering 1995) to measure how well a variable’s parent set can explain this variable. If P is small, such as less than 10, the REVEAL algorithm (Liang, Fuhrman et al. 1998) can be used to find a parent set. For each node in the second slice, the REVEAL algorithm calculates the BDe scores for all subsets of y(t), and searches for a subset which maximizes the BDe score. That is, the REVEAL algorithm can find the global optimal solution for a study with a small number of regions. For the case that m is large, we employ a heuristic search algorithm (Chen and Herskovits 2005) to identify the parent set of y(t+1) This algorithm can handle the study with thousands of variables.

After detecting the parent set of y(t+1), we use the maximum-likelihood estimation (Koller and Friedman 2009) to estimate the DBN parameters (the conditional probability tables of the DBN). That is,

where θijk is the probability of Yi = k given that parent of Yi is in state j, Nijk is the number of instances in which the variable Yi assumes state k and parents of Yi assumes state j, ri is the numbers of states of Yi, and Nij = ΣkNijk.

3.3. Classification

Our method includes two steps: network model generation and prediction. In the network model generation step, we generate a DBN model for each group, and will thereby obtain two models: M+, M−. The second step is classification. Our classifier is constructed based on sample likelihood. For a given DBN model M and a subject y1:T, the predictive distribution of yt at time t−1 is P(yt|yt−1, M). The sample likelihood of y1:T is as follows:

| (2) |

where is the variable in region i at time point t. P(yt | yt−1, M) can be obtained based on the conditional probability tables of the DBN model M. The sample likelihood of y1:T is the likelihood that y1:T is generated from M.

We use the GLR principle(Kay 1998) to generate a score which is predictive of g. For two models, M+ and M−, the GLR test statistic(Kay 1998; Fan and Jiang 2007), GLR(y1:T, M+, M−), is defined as log(y1:T; M+) - log(y1:T; M−). We will use GLR(y1:T, M+, M−) as the DBN-based score to predict g. Finally, we will use this score and other variables (clinical or imaging) to train a classifier to classify g, using standard classifiers such as support vector machines. For a new subject y1:T, we can calculate GLR(y1:T, M+, M−), then use this score to predict g.

4. Experimental Results

We validated PSDNA based on both simulated data and data from a study of normal elderly and patients with AD.

4.1. Simulated data

In this experiment, we generated simulated time-series regional morphological feature data for subjects in a case control study, and used PSDNA to discriminate subjects. For each group (g = + or −), we constructed a ground-truth DBN. This ground-truth DBN had 90 nodes representing 90 automated anatomical labeling regions. Since brain networks are sparse and nodes are not densely connected (Sporns 2011; Chen, Resnick et al. 2012), each node y(t+1) in this DBN had 1-5 parents. Based on this DBN, we generated simulated time series for 100 subjects as training data and 500 subjects as testing data. Each subject had 4 observations. Therefore, this simulated study included a training data set with 200 subjects (100 from the positive group and 100 from the negative group), and a testing data set with 1000 subjects (500 from the positive group and 500 from the negative group). We trained a classifier using the training data set and evaluated its performance based on the testing data set.

Network structure similarity is the similarity between the structure of M+ and that of M−. In DBN, one way to define network structure similarity is to compare the parent sets. Let NScommon denote nodes in the second slice, yt+1, which has identical parent set across groups. NScommon is the common network architecture for both the positive and negative groups. We defined ρ as the cardinality of the set NScommon divided by the total number of nodes in the second slice. ρ is between 0 and 1. ρ=0 means that the structure of M+ and that of M− are totally different; and ρ=1 represents that the structure of M+ and that of M− are same. Network structure similarity has a significant impact on the classification performance. We simulated data for different ρ. In our simulation, if a node y(t+1) had the same parent set across group, we set the parent set of this node as y(t). If a node y(t+1) had different parent sets across group, then its parent set was randomly generated for each group.

Table 1 shows the PSDNA’s accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for different network structure similarities. For ρ=1 representing the structure of M+ and that of M− are identical, PSDNA’s performance is close to random. For ρ=0.95 which represents 4 nodes in the second slice have different parent sets across groups, PSDNA can differentiate the positive and negative group with high accuracy. For ρ=0.8, PSDNA can perfectly separate the positive and negative group.

Table 1.

Classification performance of simulated data

| Network structure similarity | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.468 | 0.396 | 0.540 |

| 0.95 | 0.908 | 0.900 | 0.916 |

| 0.9 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.996 |

| 0.85 | 0.999 | 1 | 0.998 |

| 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

This experiment demonstrated that PSDNA can discriminate subjects if the network structures for different groups have small differences. That is, PSDNA is sensitive to the network structure difference. This experiment also demonstrated PSDNA can handle networks with a large number of nodes.

4.2. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study

We used PSDNA to discriminate cognitively normal elderly and subjects with AD. Most studies conducted to date to discriminate AD patients and normal elderly were cross-sectional and didn’t use temporal data(Colliot, Chetelat et al. 2008). Our approach to addressing this problem is based on network dynamics. Therefore, our analysis could shed light on evolving regional interactions in subjects with AD.

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the Food and Drug Administration, private pharmaceutical companies and non-profit organizations, as a $60 million, 5-year public-private partnership. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, positron emission tomography, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD. Determination of sensitive and specific markers of very early AD progression is intended to aid researchers and clinicians to develop new treatments and monitor their effectiveness, as well as lessen the time and cost of clinical trials. The Principal Investigator of this initiative is Michael W. Weiner, MD, VA Medical Center and University of California - San Francisco. ADNI is the result of efforts of many co-investigators from a broad range of academic institutions and private corporations, and subjects have been recruited from over 50 sites across the U.S. and Canada. The initial goal of ADNI was to recruit 800 subjects but ADNI has been followed by ADNI-GO and ADNI-2. To date these three protocols have recruited over 1500 adults, ages 55 to 90, to participate in the research, consisting of cognitively normal older individuals, people with early or late MCI, and people with early AD. The follow up duration of each group is specified in the protocols for ADNI-1, ADNI-2 and ADNI-GO. Subjects originally recruited for ADNI-1 and ADNI-GO had the option to be followed in ADNI-2. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

Our study included 174 cognitively normal elderly subjects and 191 subjects with AD. The variable g indicates whether a subject had AD (g = +) or was a cognitively normal elderly subject (g = −). All subjects were taken from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database.(ADNI 2014) The ADNI general eligibility criteria are described in the ADNI protocol summary page. Subjects in the ADNI study were followed up to five times (baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months). Subjects with at least two follow-ups were included in our analysis. High resolution MR images were acquired per the standard ADNI protocol. MR images were processed by ADNI investigators using methods described in (Holland, Brewer et al. 2009). Volumes of the hippocampus, entorhinal, fusiform, inferior temporal and middle temporal cortices were calculated; these structures are known to be AD-related biomarkers.(Holland, Brewer et al. 2009) We normalized regional volumes to the intracranial volume from the same MR volume. We calculated the change rate r(t, k). Then we calculated the mean and standard deviation (SD) of r(t, k) for subjects in the cognitively normal aging group, and calculated a value th(r,k) which was one SD below the sample mean. If r(t, k) is smaller than th(r,k), the structure k manifests volume loss at time t, we set its state as ‘1’ (volume loss); otherwise, we set its state as ‘0’ (normal). We used the proposed algorithm to generate an SDNA-based predictive model to predict g. In the classifier training step, we used the AdaBoost(Freund and Schapire 1996) method to construct a classifier based on the training data.

The classification performances of different methods are listed in Table 2. Classification performance was evaluated using ten-fold cross validation. We found that the method which used GLR(y1:T, M+, M−) achieved 0.80 accuracy, 0.71 sensitivity, and 0.89 specificity. This result demonstrates that the network models generated by SDNA for cognitively normal elderly and AD patients were different, and the SDNA-based score accurately predicted g. We constructed a predictive model using the baseline regional volumes of these five brain structures. This model achieved 0.77 accuracy, 0.71 sensitivity, and 0.83 specificity. We found the GLR-based predictive model was comparable to that based on the baseline biomarkers. Since a temporal process can be characterized by the baseline state and the state transition probability matrix, we built a predictive model based on the baseline biomarker characterizing the baseline state and the GLR-based score which was constructed based on the state transition probability matrix. We found this combined model achieved 0.86 accuracy, 0.85 sensitivity, and 0.87 specificity. This experiment clearly demonstrates SDNA-based network patterns can be used to discriminate subjects at the individual level.

Table 2.

Classification performance of the ADNI study

| Method | Information source | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLR | Temporal dynamics | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.89 |

| Baseline volumes | Baseline information | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.83 |

| GLR + baseline volumes | Temporal dynamics and baseline information | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.87 |

5. Discussion

We propose a new method, called PSDNA, to distinguish subjects at the individual level based on structural dynamic network patterns. For each group, PSDNA generates a DBN to represent evolving inter-regional dependencies. Then it calculates a SDNA-derived score representing that subject’s deviation from expected network patterns. This SDNA-derived score, along with other candidate predictors, are used to construct predictive models.

We validated PSDNA based on simulated data. The simulated data experiment demonstrated that PSDNA can accurately classify subjects when the network structures for different groups have small differences. For a network involving 90 brain regions, PSDNA can perfectly separate the positive and negative group when 18 nodes in the second slice have different parent sets across groups. PSDNA can separate the positive and negative group with 0.91 accuracy when 4 nodes in the second slice have different parent sets across groups. PSDNA is sensitive to the network structure difference. The simulated data experiment also demonstrated PSDNA can handle networks with a large number of nodes. In the simulated study, the brain network involves 90 nodes. Most brain atlases include a similar number of brain regions.

The ability to distinguish subjects at the individual level is crucial in the clinical trial design. To this end, many studies aimed to discriminate between the AD and control subjects in the ADNI database (Weiner, Veitch et al. 2012). We applied PSDNA to the ADNI dataset to discriminate between AD and controls. We found that the model using the SDNA-derived score, GLR(y1:T, M+, M−), achieved accuracy= 0.80, sensitivity=0.71, and specificity=0.89. When combining the SDNA-derived score and baseline regional volumes, our classifier achieved accuracy=0.86, sensitivity=0.85, and specificity=0.87. The accuracy of the model based on SDNA-derived score and baseline regional volumes is significantly better than that based on baseline volumes (two sample test for binomial proportions p-value = 0.002).

A temporal process is characterized by the baseline state and the state transition probability matrix. In PSDNA, the baseline regional volumes characterize the baseline state, and the SDNA-derived score is calculated based on the state transition probability matrix. Therefore, in the ADNI experiment, we found that combining the SDNA-derived score and baseline regional volumes is more accurate than using the SDNA-derived score or baseline regional volumes alone. This suggests that a predictive model combining different sources of information about a temporal process can achieve better performance than using them individually. To date, most MR volumetry-based studies to discriminate between AD and controls in the ADNI database had accuracy in the range of 0.76–0.89 (Weiner, Veitch et al. 2012). The mean accuracy is 0.83 (SD 0.04). The accuracy of PSDNA is higher than that of most existing studies. This demonstrates PSDNA can accurately distinguish AD and controls at the individual level.

Although our algorithm is formulated to solve a binary classification problem, it can be naturally generalized to the multi-class case. In multi-class classification, more than two groups need to be discriminated. The group membership variable g takes values from {1, 2, …, K}. The pairwise coupling method (Hastie and Tibshirani 1998) can be used to solve this problem. In pairwise coupling, a binary classifier is constructed to distinguish between each pair of classes, while discarding the rest of the classes. For a new case, a voting is performed among the classifiers and the class with the maximum number of votes is the predicted class.

PSDNA is based on the Bayesian network representation. Bayesian networks have been used to generate classifiers based on a broad range of data, including neuroimaging data (Chen and Herskovits 2006; Chen and Herskovits 2007; Chen and Herskovits 2010; Wu, Li et al. 2011; Morales, Vives-Gilabert et al. 2013). We have proposed Bayesian network based approaches to distinguish subjects at the individual level (Chen and Herskovits 2006; Chen and Herskovits 2010). The major difference between methods in (Chen and Herskovits 2006; Chen and Herskovits 2010) and PSDNA is that methods in (Chen and Herskovits 2006; Chen and Herskovits 2010) used a regular Bayesian network representation and cannot assimilate the temporal data, while PSDNA uses a DBN to represent evolving inter-regional dependencies. A related work of PSDNA is (Chen, Resnick et al. 2012). The major difference between (Chen, Resnick et al. 2012) and PSDNA is predictive modeling. Although (Chen, Resnick et al. 2012) used DBN to represent evolving inter-regional dependencies, it cannot be used to classify subjects at the individual level. PSDNA has the classification capability.

One of the limitations of PSDNA is that it is region of interest (ROI) based. ROIs are defined based on a brain atlas or prior knowledge. Each ROI is a node in the brain network. ROI based methods are widely used in brain network research because they can reduce the computation cost, facilitate comparisons across studies, and have the potential to increase signal-to-noise ratio (Craddock, Jbabdi et al. 2013, Sporns 2014). However, boundaries of ROIs may not be aligned with connectivity profiles. One way to address this problem is to use a data-driven brain parcellation strategy(Craddock, James et al. 2012), and develop a framework to merge the parcellation and network inference step (Chen and Herskovits 2005).

In the ADNI experiment, we validated the generated predictive models based on cross-validation. In this experiment, cross-validation can provide reliable estimation about a classifier’s generalizability because the sample size is large (174 cognitively normal elderly subjects and 191 subjects with AD). Many ADNI-based predictive modeling studies also used cross-validation to evaluate the classifier’s performance (Weiner, Veitch et al. 2012). A further investigation about the classifier’s generalizability can be achieved by applying the generated predictive model to an independent test dataset which has a similar study population and imaging acquisition parameters to ADNI. This is one direction of our future work.

We have presented a method to classify subjects based on structural dynamic network model based scores. Our method generates a dynamic Bayesian network model for each group, and then calculates a score representing that subject’s deviation from expected network patterns. This method is of great importance to the understanding of the network architecture of brain processes and disorders.

Highlights.

A network-based predictive modeling method for longitudinal MR data

A DBN represents complex spatiotemporal interactions among brain regions

Classifying AD patients and normal elderly using SDNA-based scores

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Eurolmmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. This work is supported by the University of Maryland’s Center for Health Informatics and Bioimaging, and the State of Maryland MPower initiative (RC and EHH).

Abbreviations:

- SDNA

structural dynamic network analysis

- DBN

dynamic Bayesian network

- PSDNA

predictive structural dynamic network analysis

- GLR

generalized likelihood ratio

References

- ADNI (2014). http://www.adni-info.org/.

- Alexander-Bloch A, Giedd JN and Bullmore E (2013). Imaging structural co-variance between human brain regions. Nat Rev Neurosci 14(5): 322–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner ES (2006). Clinical Decision Support Systems: Theory and Practice (2nd edition), Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Buch ER, Modir Shanechi A, Fourkas AD, Weber C, Birbaumer N and Cohen LG (2012). Parietofrontal integrity determines neural modulation associated with grasping imagery after stroke. Brain 135(Pt 2): 596–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore ET and Bassett DS (2011). Brain graphs: graphical models of the human brain connectome. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 7: 113–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R and Herskovits EH (2005). Graphical-model based morphometric analysis. IEEE Trans on Med Imaging 24(10): 1237–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R and Herskovits EH (2006). Network analysis of mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage 29(4): 1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R and Herskovits EH (2007). Clinical diagnosis based on Bayesian classification of functional magnetic-resonance data. Neuroinformatics 5(3): 178–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R and Herskovits EH (2010). Machine-learning techniques for building a diagnostic model for very mild dementia. NeuroImage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Resnick SM, Davatzikos C and Herskovits EH (2012). Dynamic Bayesian network modeling for longitudinal brain morphometry. Neuroimage 59(3): 2330–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colliot O, Chetelat G, Chupin M, Desgranges B, Magnin B, Benali H, et al. (2008). Discrimination between Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal aging by using automated segmentation of the hippocampus. Radiology 248(1): 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GF and Herskovits EH (1992). A Bayesian method for the induction of probabilistic networks from data. Machine Learning 9(4): 309–347. [Google Scholar]

- Craddock RC, James GA, Holtzheimer PE 3rd, Hu XP and Mayberg HS (2012). A whole brain fMRI atlas generated via spatially constrained spectral clustering. Hum Brain Mapp 33(8): 1914–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock RC, Jbabdi S, Yan CG, Vogelstein JT, Castellanos FX, Di Martino A, et al. (2013). Imaging human connectomes at the macroscale. Nat Methods 10(6): 524–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J and Jiang J (2007). Nonparametric inference with generalized likelihood ratio tests. Test 16(3): 409–444. [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B (2012). FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 62(2): 774–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund Y and Schapire R (1996). Experiments with a new boosting algorithm. Machine Learning: Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference,: 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T and Tibshirani R (1998). Classification by pairwise coupling. Ann. Statist 26(2): 451–471. [Google Scholar]

- Heckerman D and Chickering DM (1995). Learning Bayesian Networks: The Combination of Knowledge and Statistical Data. Machine Learning: 20–197. [Google Scholar]

- Holland D, Brewer JB, Hagler DJ, Fennema-Notestine C and Dale AM (2009). Subregional neuroanatomical change as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(49): 20954–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW and Smith SM (2012). FSL. NeuroImage 62: 782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SM (1998). Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processin, Prentice Hal. [Google Scholar]

- Koller D and Friedman N (2009). Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques, The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Fuhrman S and Somogyi R (1998). Reveal, a general reverse engineering algorithm for inference of genetic network architectures. Pac Symp Biocomput: 18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, Newmark R, Chu KW and Buchsbaum MS (2005). Correlations between MRI-assessed volumes of the thalamus and cortical Brodmann’s areas in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 75(2–3): 265–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montembeault M, Joubert S, Doyon J, Carrier J, Gagnon JF, Monchi O, et al. (2012). The impact of aging on gray matter structural covariance networks. Neuroimage 63(2): 754–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales DA, Vives-Gilabert Y, Gomez-Anson B, Bengoetxea E, Larranaga P, Bielza C, et al. (2013). Predicting dementia development in Parkinson’s disease using Bayesian network classifiers. Psychiatry Res 213(2): 92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (2013). Advisory Committee to the Director, Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Working Group, Interim Report — Executive Summary. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J (1988). Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems, Morgan Kaufmann. [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Halchenko YO and Hanson SJ (2009). Decoding the large-scale structure of brain function by classifying mental States across individuals. Psychol Sci 20(11): 1364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AT and Evans AC (2013). Structural networks in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23(1): 63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato JR, Hoexter MQ, Oliveira PP Jr., Brammer MJ, Murphy D and Ecker C (2013). Inter-regional cortical thickness correlations are associated with autistic symptoms: a machine-learning approach. J Psychiatr Res 47(4): 453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPM (2014). SPM - Statistical Parametric Mapping. [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O (2011). Networks of the Brain. Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O (2014). Contributions and challenges for network models in cognitive neuroscience. Nat Neurosci 17(5): 652–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Cairns NJ, Green RC, et al. (2012). The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimers Dement 8(1 Suppl): S1–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li R, Fleisher AS, Reiman EM, Guan X, Zhang Y, et al. (2011). Altered default mode network connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease--a resting functional MRI and Bayesian network study. Hum Brain Mapp 32(11): 1868–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski BA, Anderson JS, Froehlich AL, Prigge MB, Nielsen JA, Cooperrider JR, et al. (2012). scMRI reveals large-scale brain network abnormalities in autism. PLoS One 7(11): e49172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski BA, Gennatas ED, Zhou J and Seeley WW (2010). Network-level structural covariance in the developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(42): 18191–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]