Abstract

Cadherin-like and PC-esterase domain containing 1 (CPED1) is an uncharacterized gene with no known function. Human genome wide association studies (GWAS) for bone mineral density (BMD) have repeatedly identified a significant locus on Chromosome 7 that contains the gene CPED1, but it remains unclear if this gene could be causative. While an open reading frame for this gene has been predicted, there has been no systematic exploration of expression or alternate splicing for CPED1 in humans or mice. Using mouse models, we demonstrate that Cped1 is alternately spliced whereby transcripts are generated with exon 3 or exons 16 and 17 removed. In calvarial-derived pre-osteoblasts, Cped1 utilizes the predicted promoter upstream of exon 1 as well as alternate promoters upstream of exon 3 and exon 12. Lastly, we have determined that some transcripts terminate at the end of exon 10 and therefore do not contain the cadherin like and the PC esterase domains. Together, these data suggest that multiple protein products may be produced by this gene, with some products either lacking or containing both the predicted functional domains. Our data provide a framework upon which future functional studies will be built to understand the role of this gene in bone biology.

Keywords: alternative splicing, tissue expression profile, uncharacterized gene

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a polygenic disease of progressive bone loss culminating in debilitating low-trauma fractures (bone failure) and increased mortality risk [1, 2]. Heritability estimates from twin and family studies show that up to 89% of the variation in bone mineral density (BMD), a clinically measurable predictor of osteoporotic fracture risk, is determined by genetics. Human GWAS for BMD and fracture risk have repeatedly identified a significant locus at 7q31.31 containing the uncharacterized gene Cadherin-like and PC-esterase Domain-containing 1 (CPED1, also known as C7ORF58) [3–7]. Additionally, associations with BMD have been described for variants within CPED1 in GWAS focused on bone accretion in pediatric populations [8–10].

CPED1 has no verified function in humans or in mice. Given the repeated genetic associations between BMD and the locus containing CPED1, we set out to characterize expression of its murine ortholog, Cped1, to lay the foundation for future studies of this gene in bone disease. In mice, Cped1 maps to Chromosome 6 at 21.98 to 22.25 Mb (GRCm38/mm10 assembly) or 8.86 cM. The NCBI Reference Sequence for Cped1 indicates that the full-length open reading frame (ORF) should be 4,898 base pairs (bp) in length and is divided into 22 exons (NM_001081351.1). The corresponding protein (NP_001074820.1) is predicted to be 1,026 amino acids (aa) in length and putatively contains an N-terminal signal peptide that should direct the protein product to the secretory pathway, a cadherin-like domain, and a PC esterase domain with predicted acyltransferase and acylesterase activity for the modification of glycoproteins [11]. To date, neither tissue specific expression nor alternative splicing of Cped1 transcript(s) has been experimentally verified for the mouse. We have identified multiple splice variants for Cped1 in bone including transcripts with alternate 5’- and 3’-UTRs and novel promoter regions, potentially leading to the generation of numerous putative protein isoforms. Our data show that Cped1 is widely expressed in mouse tissues and cell lines including bone and bone cells, but is absent from RAW264.7 macrophage/monocyte cells and circulating leukocytes from whole blood. The present study represents a step forward in the characterization of this previously unstudied gene with potential relevance to the maintenance and regulation of bone mass.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal procedures were performed according to protocols reviewed and approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Male C57BL/6J (B6) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock Number 000664) for tissue harvesting and RNA analyses. All mice were fed Laboratory Autoclavable Rodent Diet 5010 (LabDiet, Cat no. 0001326) and had ad lib. access to food and water. The mice were maintained on a 12hr:12hr light:dark cycle.

2.2. Cell culture

C3H10T1/2 cells (ATCC CCL-226) were cultured according to manufacturer’s recommendations in Basal Medium Eagle (Hyclone, Cat no. SH30157.01) supplemented with 10% fetal-bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. To initiate differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells into osteoblast-like cells, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 4 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 100ng/mL recombinant BMP-2 (R&D Systems, Cat no. 355-BM-050) were added to the media. RAW 264.7 cells (ATCC Cat no. TIB-71) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, Cat no. 11885-092) supplemented with 10% fetal-bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. MC3T3-E1, Subclone 4 cells (ATCC, Cat no. CRL-2593) were cultured in α-MEM (Gibco, Cat no. A1049001) supplemented with 10% fetal-bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, and 4 mM β-glycerophosphate. All cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Culture media was replaced every two days.

2.3. Extraction of total RNA from homogenized mouse tissues and cDNA synthesis

Male, 12 week old B6 mice were anesthetized, exsanguinated, and perfused with heparinized saline and eight organs (calvarial bone, skeletal muscle [vastus medialis], heart, kidney, testis, liver, lung, and whole brain) were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Solid tissues were homogenized using a Bullet Blender Gold (Next Advance). Briefly, a mixture of sterile, RNase-free 2.0 mm (NextAdvance, Cat no. ZrOB20) and 0.5 mm zirconium oxide beads (Cat no. ZrOB05-RNA), and 0.5 mL of ice cold TRIzol (Thermo Fisher, Cat no. 15596026) was added to each mouse tissue. Tissue was homogenized for 1-8 minutes, and the homogenate was transferred to a clean microcentrifuge tube. For white blood cells (WBC), whole blood was collected from the submandibular vein, and the buffy coat was isolated via centrifugation, combined with TRIzol and the cells were lysed by repeated pipetting. For all tissues, the aqueous phases were extracted with chloroform, mixed with an equal volume of 100% ethanol, and transferred to a GENEJet RNA Purification column for purification (Thermo Scientific, Cat no. K0731). Total RNA was DNase-treated (Invitrogen, Cat no. 18068-015) and reverse transcribed into cDNA (Invitrogen, Cat no. 18080-051). Reactions were primed using a mixture of Oligo dT and random hexamers. PCR amplification of an intergenic region on Chromosome 6 was used to verify the absence of genomic contamination.

2.4. Qualitative detection of Cped1 isoforms via reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Tissue cDNA (25-100 ng/reaction) was subjected to PCR to identify splice variants and all known 5’- and 3’-UTRs (GoTaq Green Mastermix, Promega, Cat no. M7123 for products < 500 bp or Advantage 2 Polymerase Mix, CLONTECH, Cat no. 639201 for products > 500 bp). Primer sequences are listed in supplemental Tables 1–3.

2.5. Generation of Cped1 promoter luciferase reporter constructs.

Potential Cped1 promoter regions were generated from B6 gDNA using PCR and cloned into pGL4.10 [luc2/SV40] luciferase reporter constructs (Promega, Cat no. E665A). MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with Cped1 promoter-driven luc2 reporter plasmids or empty vector (500ng) and co-transfected with a renilla luciferase expression plasmid (5ng). Concurrent transfection, the cells were subjected to osteogenic differentiation media. Luciferase signal was measured with an Optocomp I Luminometer (MGM Instruments) 24 hours after transfection. Firefly luciferase was quantitated in three biological replicates and normalized to SV40 renilla luciferase.

2.6. Plasmid construction for Sanger sequencing and confirmation of splice variants

A TOPO TA cloning kit (Thermo, Cat no. K4500-01) was used to generate plasmids containing template for sequencing according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RT-PCR products were inserted into pCR2.1-TOPO vector and chemically transformed into One Shot competent E. coli cells. Color-based clone selection of bacterial colonies was performed using Lysogeny Broth (LB) agar plates containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin, 40 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal) in dimethylformamide (DMF), and 100 nM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) in water. Positive colonies were grown to stationary phase in LB with 50µg/mL ampicillin. Plasmids were extracted from 5 mL of overnight LB cultures using QIAprep Miniprep (Qiagen, Cat no. 27104) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primer extension sequencing was performed by GENEWIZ, Inc (South Plainfield, NJ) using Applied Biosystems BigDye version 3.1. The reactions were then run on Applied Biosystem’s 3730xl DNA Analyzer.

2.7. Quantitation of Cped1 copy number

Plasmid concentration was measured using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer, and copy number was calculated as previously described [12, 13]. Calibration curves ranging from a concentration of 1×103 to 1×107 copies were generated for each PCR reaction, and qRT-PCR was performed to quantify input from MC3T3-E1 cells (N=3). Values represent copies/25 ng cDNA +/− SEM.

2.8. Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. A one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to determine statistical differences between luciferase activity of Cped1 promoter constructs relative to the empty vector control. Cped1 copy number expression was compared between each exon at days 2 and 7 of MC3T3-E1 cell osteogenic differentiation using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cped1 is alternatively spliced leading to transcripts without exon 3, or 16 & 17.

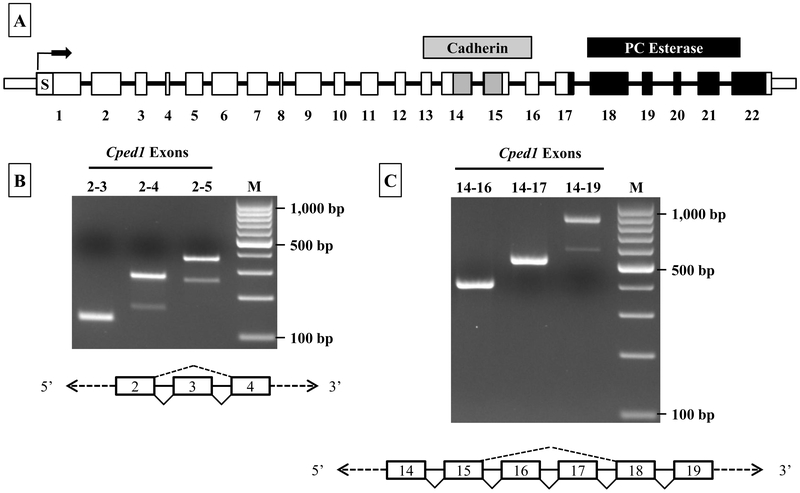

Although the NCBI reference sequence for Cped1 (NM_001081351.1) indicates that the primary transcript contains 22 exons, transcription of this predicted ORF has yet to be validated in murine models. Expression of each of the 22 predicted exons of Cped1 was verified by multi-exon RT-PCR on cDNA from calvarial bone, using a tiled approach such that the entire transcript was examined (Supplementary Fig. 1, summarized in Fig. 1A). During this approach, evidence of possible alternative splicing was observed. When examined further, two RT-PCR products were generated by PCR wherein the primers were located in exons 2 and 4, respectively (Fig. 1B). Based on product size and subsequent confirmation by Sanger sequencing, we determined that exon 3 could be alternately spliced from the transcript. While this would result in a protein product that is smaller relative to that translated from the full-length transcript, this splicing event retains the downstream ORF and should yield a protein product that is otherwise identical in amino acid sequence to the full length protein product. Similarly, when using primers located in exons 14 and 19, two products were generated that corresponded to a splice variant lacking exons 16 and 17 (Fig. 1C). Sanger sequencing was used to confirm this result. The splicing of exons 16 and 17 together, like for the exon 3 splice event, is an in-frame splicing event and should not disrupt the otherwise predicted ORF.

Figure 1: Cped1 is alternatively spliced leading to the generation of multiple mRNA isoforms.

A) Diagrammatic view of Cped1 mRNA (boxes represent exons) detailing the predicted exons and putative functional domains (S = signal peptide, Cadherin = cadherin-like domain, and PC esterase domain). B & C) Total RNA from male, 12 week old C57BL/6J mouse calvaria was analyzed via RT-PCR for the presence or absence of splice variants. Diagrams depict the splicing events (exon skipping) for exons 3, 16, or 16 and 17.

3.2. Identification of additional 5’- and 3’-UTRs in Cped1 transcripts & unique promoters.

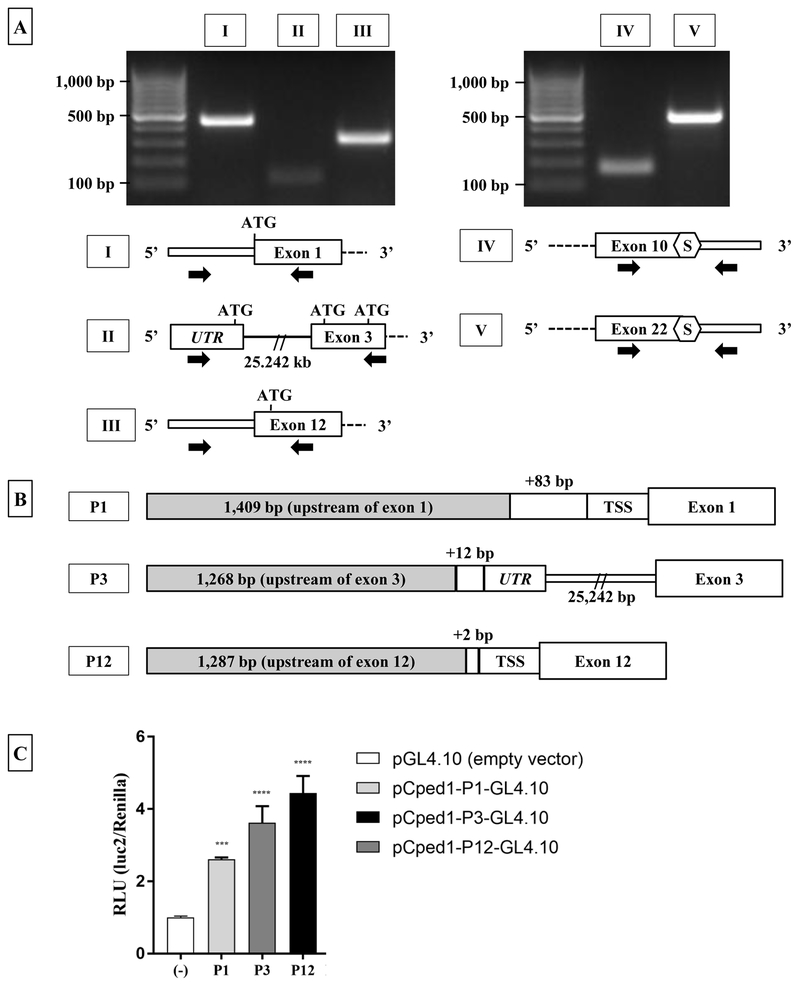

Publicly available data at NCBI [14] and ENSEMBL [15] indicated that truncated Cped1 transcripts may be expressed, suggesting that multiple 5’- and 3’-UTRs may exist. To confirm expression of the UTR regions of full-length transcript, RT-PCR primers residing in either the 5’-UTR and exon 1 or the 3’-UTR and exon 22 were used for PCR amplification (Fig. 2A). Two products corresponding to the full-length 5’-UTR (Fig. 2A Band I) and 3’-UTR (Fig. 2A, Band V) were generated.

Figure 2: Calvaria express multiple Cped1 transcripts with alternate 5’- and 3’-UTR, and utilize alternate promoters for transcription.

A) RT-PCR of Cped1 transcripts demonstrates the expression of alternate 5’- and 3’-UTRs. Thick and thin rectangles represent exon and UTRs, respectively, and solid lines represent introns. White hexagons labeled ‘S’ represent predicted stop codons as identified by analysis of nucleotide sequence. Black arrows represent the approximate target location of forward and reverse primers for PCR of Cped1 transcripts. B) Predicted promoter regions upstream of exon 1 (P1), exon 3 (P3), and exon 12 (P12) are transcriptionally active in MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts during osteogenic differentiation. Fold change between luciferase constructs P1, P3, and P12 vs. empty vector (pGL4.10) was detected. Data is represented as change in relative light units (RLU) of firefly luciferase normalized to renilla luciferase 24 hours post-transfection. Results are expressed as mean +/− SD, N=3. TSS: translational start site. Statistical differences were detected via one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Data from the ENSEMBL genome browser suggested that two additional 5’-UTRs may be represented in the transcriptome. The first alternate 5’-UTR is predicted upstream of exon 3 (ENSMUST00000156621.1). It is located in an intron between the 2nd and 3rd exons, but is not contiguous with the exon 3 ORF as it is 25,242 bp upstream of exon 3. RT-PCR primers located in this upstream region and exon 3 respectively did generate a PCR product, and sequencing confirmed that this is a spliced UTR (Fig. 2A, Band II). This suggests that a Cped1 transcript variant lacking the first two exons and the predicted signal peptide is expressed. The second potential alternate 5’-UTR located immediately before exon 12 (ENSMUST00000154734.1) was evaluated using primers located in the predicted 5’-UTR and exon 12. This yielded a PCR product of the expected molecular weight, and the sequence of this product was confirmed (Fig. 2A, Band III).

Data from ENSEMBL also predicted expression of a truncated Cped1 transcript with an ORF 2,002 bp long divided into 10 exons (ENSMUST00000115382.7). These 10 exons are the same as the first 10 exons of the full-length transcript. This transcript putatively codes for a 473 amino acid protein (Uniprot: D3YUQ2). RT-PCR primers located in exon 10 and immediately downstream in the predicted 3’-UTR were used to generate a PCR product to test if this putative 3’-UTR was represented in the total RNA from these cells (Fig. 2A, Band IV). Using Sanger sequencing, we confirmed that there is a stop codon 15 bp downstream of the annotated end of the 10th exon that would extend this ORF and suggests that this 10-exon transcript could generate a protein product. Altogether, these results indicate that there are multiple transcripts transcribed from this gene in calvarial tissue and this adds to the diversity of potential protein products made from this single gene.

To test for a functional promoter upstream of these 5’ -UTRs, sequences upstream of exon 1 (control), exon 3, and exon 12 were cloned into a promoter-less luciferase reporter construct (Fig. 2B). Upon delivery to MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts treated with osteogenic media, a robust increase in luciferase activity was observed at day 2 of differentiation compared to the empty vector for each reporter construct (Fig. 2C). This indicated that these three promoters are likely functional and may be utilized during osteoblast differentiation.

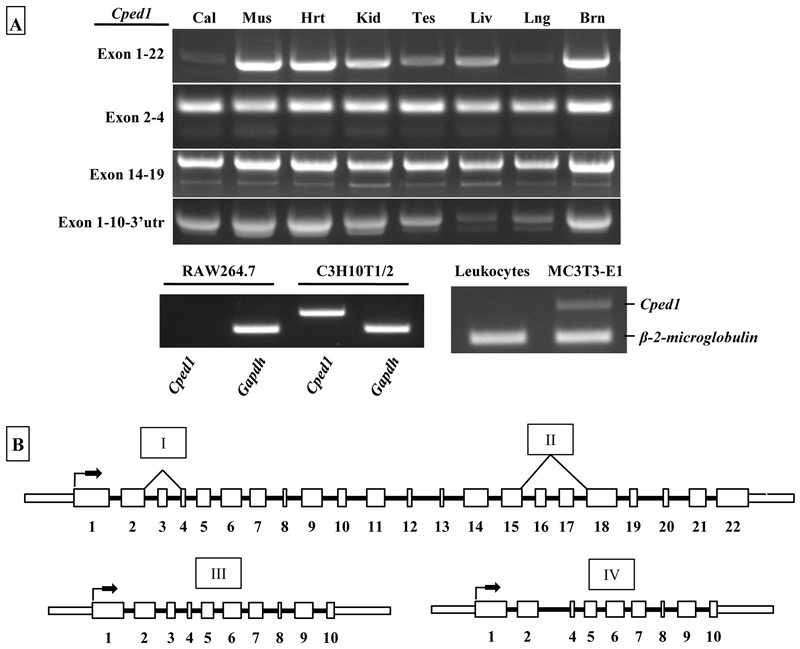

3.3. Cped1 transcripts are uniformly expressed in a variety of whole mouse tissues, including bone, but absent in RAW264.7 cells and whole blood leukocytes.

To assess the tissue distribution of Cped1 expression, total RNA from eight solid organs (calvarial bone, muscle, heart, kidney, testis, liver, lung, and brain), as well as unstimulated leukocytes isolated from whole blood, from male, 12 week old B6 mice were analyzed via RT-PCR for Cped1 transcripts. Primers designed to amplify full-length Cped1 (exons 1 to 22) generated PCR products in each organ tested (Fig. 3). Additionally, expression of each previously identified splice variant (lacking exon 3, lacking exons 16 & 17, and the truncated exon 1-10 product) were confirmed in all eight solid organs. From these data we concluded that Cped1 expression appears to be uniformly present in solid tissues and we could not identify any organ specific splice events. Interestingly, the unstimulated leukocytes did not express Cped1, suggesting that circulating, non-adherent cells do not express Cped1. A summary of these data was constructed to show each of the identified splice variants of Cped1 that are expressed (Fig. 3). To test whether cultured homogeneous cell populations expressed Cped1, we tested the monoctye/macrophage RAW264.7 cell line which can be directed down the osteoclast lineage. Interestingly, primers amplifying a segment of the first 2 exons of Cped1 generated no PCR product in these cells, whereas multipotent C3H10T1/2 and calvarial derived pre-osteoblasts, MC3T3-E1 cells stimulated with osteogenic media showed expression of Cped1 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Cped1 isoforms are widely expressed in whole mouse organs but absent in RAW264.7 cells and circulating leukocytes.

A) RT-PCR for Cped1 transcripts was performed in eight C57BL/6J mouse tissues (Cal: calvaria, Mus: skeletal muscle [rectus femoris], Hrt: heart, Kid: kidney, Tes: testis, Liv: liver, Lng: lung, Brn: brain). Expression of a segment of exons 1 and 2 of Cped1 was tested in RAW264.7 monocytes/macrophases, multipotent C3H10T1/2 cells, MC3T3-E1 calvaria-derived pre-osteoblasts, and whole blood leukocytes. B) Summary schematic of alternative splicing suggests a diverse expression pattern for Cped1. Each of the identified and confirmed Cped1 transcripts including the splicing events (depicted above with roman numerals) is listed. Thick and thin rectangles represent exon and UTRs, respectively, and solid lines represent introns. Arrows indicate putative start sites for initiation of translation.

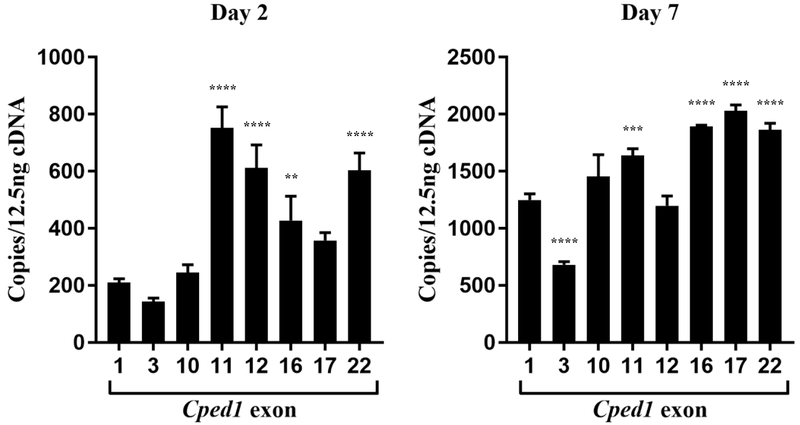

3.4. Cped1 exon expression varies due to alternative splicing and time of differentiation.

In order to compare the expression of individual Cped1 exons, a full-length expression plasmid containing Cped1 exons 1-22 was generated to use as a standard for calculating transcript copy number. Quantitation of Cped1 exon expression at day 2 of osteogenic differentiation revealed that transcripts containing exons 1 to 10 are expressed at lower levels than are transcripts containing exons 11 to 22. As would be expected based on the predicted alternative splicing described above, lower copy numbers relative to adjacent exons were observed for exon 3, 16, and 17 (Fig 4). By day 7 of differentiation, expression of exons in the latter half of the transcript remained significantly elevated compared to exon 1, except for exon 12 (Fig 4). Exon 3 was significantly reduced compared to adjacent exons indicating that this splicing event persists while exons 16 and 17 were no longer reduced. Overall, these results suggest that as these cells differentiate, the quantity of each exon changes potentially due to a shift in the abundance of a particular Cped1 isoform.

Figure 4: Cped1 exon expression varies due to alternative splicing and time of differentiation.

The number of copies of Cped1 exons 1, 3, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, and 22 were determined in MC3T3-E1 cells (N=3) by qRT-PCR at days 2 and 7 of osteogenic differentiation. Values represent transcript copies per 12.5 ng of cDNA input. Error bars represent SEM of technical and biological replicates. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

We have generated some of the first data characterizing the Cped1 gene in mice, including the first description of alternate promoter usage and alternative splicing events. Our data confirms that full-length Cped1 transcript contains 22 exons and is expressed in all whole mouse organs tested. The interesting exceptions to this pervasive expression pattern are the lack of expression of Cped1 in the monocyte/macrophage RAW264.7 cell line and circulating leukocytes in the blood. The RAW264.7 cell line can be differentiated into osteoclasts (bone resorbing cells) given appropriate growth factors and cytokines, and are commonly used to study osteoclastogenesis. Given that Cped1 is expressed in many whole organs but is absent in a monocyte/macrophage cell line and leukocytes in the blood, we hypothesize that cells expressing Cped1 reside in the fibrous extracellular matrix at the organ or tissue level and that circulating cells may lack Cped1 expression.

Data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project [16] indicates that CPED1 is expressed in a variety of tissues in humans, but not in any of the regions of the brain. This is contrary to our mouse data as we show robust expression, including alternative splicing, in whole brain tissue. However, public databases such as BioGPS show limited expression of Cped1 in mouse brain tissues [17]. Specifically, low levels of Cped1 expression are reported for the brain including the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and dorsal root ganglia. Mouse transcriptome data available from the ENCODE Project indicate minimal expression of Cped1 in the developing central nervous system (E11.5 to E18) and whole mouse brain (E14.5) [18].

GTEx annotation documents a total of 10 transcript isoforms for CPED1 and up to 30 possible exons. Upon closer inspection of each transcript, the data at GTEx appears to corroborate our mouse data where Cped1 contains only 22 exons. Redundant numbering of the exons from each of the transcripts resulted in an overestimation of the number of unique exons in this database. There are, however, references to novel regions in some of the predicted mRNA transcripts in human tissues of unknown significance. For example, data in the GTEx database suggests a potential splice variant lacking exon 2 may exist in humans, but we found no evidence of this isoform in mouse. Bone is not currently one of the 53 tissues represented at GTEx, representing a limitation of this comparison to the GTEx data.

CPED1 putatively contains an N-terminal signal peptide that should direct the translated protein to the secretory pathway for transport to cell membrane [11]. Online prediction software also suggests that the polypeptide is secreted and is predicted to be cleaved after the 34th amino acid coded in exon 1 [19]. The latter half of Cped1 transcript codes for two potential functional domains; a beta-sandwich domain with a cadherin-like fold, and a PC esterase domain with an N-terminal fused ATP-grasp domain[11]. The cadherin-like domain is most similarly related to cell-wall binding domains seen in prokaryotic organisms and is predicted to function in carbohydrate-binding [11]. The ATP-grasp domain fused to the PC esterase domain has similarity to the tubulin-tyrosine ligase family of proteins, suggesting that the PC esterase domain interacts with and modifies glycoproteins via the addition of amino acids [11]. Overall, these predicted domains offer evidence of potential function at the cell membrane and/or extracellular matrix that seem to suggest modification of structural elements.

Approximately 90-95% of mammalian genes are alternately spliced which dramatically increases the diversity of mRNA and protein products [20–22]. Secreted extracellular matrix proteins, including Type I and Type II collagen, are commonly alternately spliced leading to a wide range of functional capabilities [23]. This alternative splicing can include alternate exon usage, exon skipping, as well as the use of alternate promoters to initiate transcription, [22]. Cped1 exhibits alternative splicing, namely by way of exon skipping. In our initial characterization of Cped1 alternative splicing in adult mouse calvarial bone, we identified exon skipping of exon 3 and exons 16 and 17 combined (Fig 1). Splicing of exon 3 is an in-frame deletion that maintains the ORF of the putative protein. This splicing event is detected both in the full-length (exons 1-22) and truncated (exons 1-10) Cped1 transcripts. No functional domains are predicted for this region of the protein, thus rendering the functional significance of these splicing events unknown[11]. The PC-esterase domain of the putative protein product is predicted to be transcribed by the last 30 nucleotides of exon 17 through the first 70 aa of exon 22. Alternative splicing of exons 16 and 17 is therefore predicted to remove 10 aa (ELQQCLQGRK) of the PC-esterase domain and 85 aa in total. The removal of charged (E, K, R) and polar (Q, C) amino acids coded by exon 17 could affect the folding properties of this predicted protein and has the potential to significantly alter protein function. The truncated Cped1 isoform which spans exons 1-10 lacks the coding sequence for the two predicted functional domains (cadherin-like and PC-esterase) and would suggest an alternate function for this smaller protein.

In addition to alternative splicing, three unique promoter regions were identified (Fig. 2B). Our data show that these promoters are expressed and transcriptionally active during osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 2C). The luciferase activity of the three promoter constructs was approximately equal, suggesting that all three promoters are have a relevant role in early differentiation. Additionally, the abundance of exons expressed downstream of these active promoters appears to be a dynamic state and fluctuates based on time of differentiation (Fig. 4). Transcripts produced by the promoters before exon 3 or exon 12 would lack the predicted signal peptide located in exon 1 which could affect cellular localization. Altogether, given the number of predicted isoforms and active promoters, we conclude that the Cped1 gene is complexly regulated during osteoblast differentiation. We hypothesize that the role of CPED1 may be multifaceted and highly regulated given this diversity of transcripts with or without various predicted functional domains. Further analysis of isoform quantities and cellular localization are necessary to help address these outstanding issues.

In conclusion, we have provided some of the first data describing expression and alternative splicing of Cped1, and these data are critical for directing future studies. Further characterization of Cped1 in vitro and genetic ablation studies using transgenic animals will provide a framework for in vivo studies designed to provide a link between human GWAS data and a potential contribution of this gene to the regulation of bone mass.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIH/NIAMS under Award Numbers R21 AR060981 and R01 AR060234 awarded to CLAB, as well as the following: NIH/NIAMS 5T32 AR053459 training grant and, NIH/NIAMS Core Center Grant 1P30 AR069655.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest (all authors): None

References Cited:

- 1.Raisz LG, Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest, 2005. 115(12): p. 3318–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bliuc D, et al. , Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA, 2009. 301(5): p. 513–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estrada K, et al. , Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet, 2012. 44(5): p. 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng HF, et al. , Whole-genome sequencing identifies EN1 as a determinant of bone density and fracture. Nature, 2015. 526(7571): p. 112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng HF, et al. , WNT16 influences bone mineral density, cortical bone thickness, bone strength, and osteoporotic fracture risk. PLoS Genet, 2012. 8(7): p. e1002745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koller DL, et al. , Meta-analysis of genome-wide studies identifies WNT16 and ESR1 SNPs associated with bone mineral density in premenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res, 2013. 28(3): p. 547–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medina-Gomez C, et al. , Life-Course Genome-wide Association Study Meta-analysis of Total Body BMD and Assessment of Age-Specific Effects. Am J Hum Genet, 2018. 102(1): p. 88–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina-Gomez C, et al. , Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Scans for Total Body BMD in Children and Adults Reveals Allelic Heterogeneity and Age-Specific Effects at the <italic>WNT16</italic> Locus. PLoS Genet, 2012. 8(7): p. e1002718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesi A, et al. , A trans-ethnic genome-wide association study identifies gender-specific loci influencing pediatric aBMD and BMC at the distal radius. Hum Mol Genet, 2015. 24(17): p. 5053–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemp JP, et al. , Phenotypic Dissection of Bone Mineral Density Reveals Skeletal Site Specificity and Facilitates the Identification of Novel Loci in the Genetic Regulation of Bone Mass Attainment. PLoS Genet, 2014. 10(6): p. e1004423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anantharaman V and Aravind L, Novel eukaryotic enzymes modifying cell-surface biopolymers. Biol Direct, 2010. 5: p. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whelan JA, Russell NB, and Whelan MA, A method for the absolute quantification of cDNA using real-time PCR. Journal of Immunological Methods, 2003. 278(1-2): p. 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C, et al. , Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol, 2006. 123(3): p. 273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Leary NA, et al. , Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016. 44(D1): p. D733–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zerbino DR, et al. , Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res, 2018. 46(D1): p. D754–D761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consortium GT, The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(6): p. 580–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu C, et al. , BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol, 2009. 10(11): p. R130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yue F, et al. , A comparative encyclopedia of DNA elements in the mouse genome. Nature, 2014. 515(7527): p. 355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiller K, et al. , PrediSi: prediction of signal peptides and their cleavage positions. Nucleic Acids Res, 2004. 32(Web Server issue): p. W375–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblihtt AR, et al. , Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2013. 14(3): p. 153–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scotti MM and Swanson MS, RNA mis-splicing in disease. Nat Rev Genet, 2016. 17(1): p. 19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelemen O, et al. , Function of alternative splicing. Gene, 2013. 514(1): p. 1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd CD, et al. , Alternate Exon Usage is a Commonly Used Mechanism for Increasing Coding Diversity Within Genes Coding for Extracellular Matrix Proteins. Matrix, 1993. 13(6): p. 457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.