Abstract

Background

Cognitive function has been suggested to be correlated with mortality, while studies regarding the association among the very elderly population with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are extremely limited.

Aim

To explore the association between cognitive function and mortality among the very elderly Chinese population with CKD.

Methods

This prospective study included 163 Chinese participants aged 80 years or older with CKD. CKD was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Cognitive function was evaluated using the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) at baseline. Participants were divided into three groups based on the MMSE score. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the contribution of cognitive function to mortality.

Results

During a median follow-up of 28 months, 24 (14.7%) participants died, and 14 of the events were cardiovascular death. After making adjustment for potential confounders, every 1-point increase of MMSE score was associated with 29% decreased risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted hazards ratio [HR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58–0.87) and 39% decreased risk of cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44–0.83). Compared with participants with top category of MMSE score, the adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among those with bottom category of MMSE score were 8.18 (95% CI, 2.05–32.54) and 14.72 (95% CI, 1.65–131.16).

Conclusion

Cognitive function was associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among the very elderly population with CKD.

Keywords: cognitive function, mortality, chronic kidney disease, very elderly

Introduction

The prevalence of both cognitive impairment and chronic kidney disease (CKD) increase with age,1–3 with an estimated prevalence of approximately 20%–30% and 30%–50% in the very elderly aged 80 years or older.1,3,4 Cognitive impairment and CKD have already been major public health problems in the very elderly and pose an enormous social and economic burden.5

Cognitive impairment is common in individuals with CKD.6 People with CKD intend to have lower cognitive function and higher risk of cognitive impairment than those without CKD.7–9 Furthermore, more advanced stages of CKD were found to be associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment, with the greatest cognitive impairment observed in those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).10 Meanwhile, cognitive impairment is associated with an increased risk of mortality in people with CKD and ESRD.11,12

To the best of our knowledge, longitudinal studies investigating the association between cognitive function and mortality in a very elderly population with CKD are extremely limited. Therefore, we initiated the present study to explore the association among a very elderly Chinese population (≥80 years) with predialysis CKD.

Study population and methods

Study population

In 2004, 284 participants aged 80 years or older from Shandong province of People’s Republic of China were recruited to participate in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial designed to establish the benefits and risks of antihypertensive treatments.7,13 All participants had no clinical diagnosis of dementia, and creatinine levels were <150 mol/L at baseline. Cognitive function was assessed with the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) at baseline. Participants were randomly assigned to receive the antihypertensive treatment or placebo. Patient randomization was initiated at the coordinating office on receipt of the completed entry form. Patients will be stratified into four groups on the basis of sex and age (ie, 80–89 years and ≥90 years). Restricted randomization was employed to ensure equal allocation per group. This trial was stopped in 2007. Full details of the protocol have been published elsewhere.14 Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the trial was approved by Ethics Committee of Beijing Hypertension League Institute.

Evaluation of cognitive function

All participants were assessed with the MMSE at baseline. MMSE is a standardized, brief, and extensively used method to assess individuals’ cognitive function.15 The MMSE score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher score indicating better cognitive function. The MMSE assesses attention, orientation, language, the ability to follow simple verbal and written commands, and immediate and short-term recall. The scores were calculated by the coordinating office staff.14

Evaluation of kidney function at baseline

Baseline serum creatinine levels were measured by Jaffe’s kinetic method using a Hitachi 7600 automated biochemical analyzer in all participants. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the modified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation developed using data from Chinese participants with CKD.16 CKD was defined as an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. All participants had an eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Evaluation of covariates at baseline

Detailed descriptions of those procedures have been published elsewhere.14 Baseline blood pressure measurements were collected for all participants. Information regarding previous cardiovascular disease (CVD; including myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and stroke) and lifestyle behaviors were obtained using a questionnaire. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Hemoglobin, fasting glucose, uric acid, and total cholesterol levels were measured at baseline.

Mortality

Participants were followed up for up to 3 years after enrollment. The primary end point was all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Mortality status (date and causes of death) was monitored through the hospital’s computerized medical records system and contact with primary physicians. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as death due to myocardial ischemia, or infarction, or stroke, or cardiac arrest. Survival time was calculated as the number of months from the baseline assessment until one of the following: death, or end of the study observation period (October 2007, at a maximum of 49 months).

Statistical analysis

Participants were divided into three MMSE groups based on the tertile of the MMSE score. Standard descriptive statistics were used to assess the baseline characteristics and to test differences in the characteristics between three groups. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]). Categorical variables were presented as proportions. Data were compared using an analysis of variance test or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

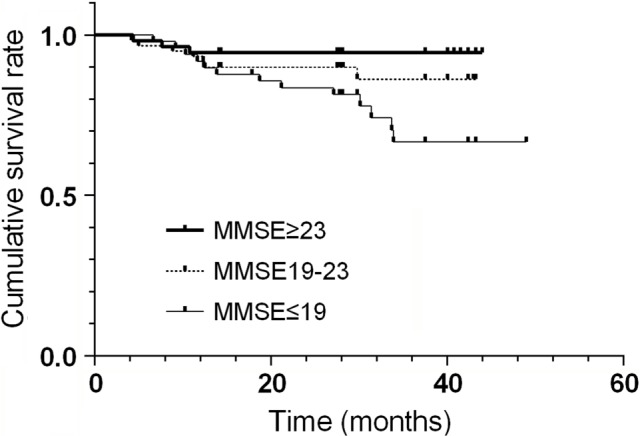

The comparison of the survival rates among three cognitive function groups was conducted by the Kaplan–Meier curve, followed by a log-rank test to assess the significance between the survival curves.

Cox proportional hazards regression were built to analyze the association between baseline cognitive function and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality (presented as hazard ratio [HR] and 95% CI). First, we analyzed the MMSE score as a continuous variable (per 1-point increase). Multivariate models were constructed to adjust for potential confounding variables associated with cognitive function and/or mortality, including age (continuous), gender (female vs male), body mass index (continuous), current smokers (yes vs no), previous CVD (yes vs no), treatment group (yes vs no), fasting blood glucose level (continuous), total cholesterol level (continuous), uric acid level (continuous), diastolic blood pressure (continuous); baseline diastolic blood pressure was reported to be associated with incident dementia in a previous study,17 and eGFR level (continuous). Crude and adjusted HRs with 95% CIs are presented. We also analyzed the MMSE score as a three categorical variable, using the same strategy.

All P-values are two-tailed. Statistical tests were performed using the SAS statistical package version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Altogether, 163 participants were diagnosed with CKD at baseline. During a median follow-up of 28 months (IQR 19–40 months), 24 (14.7%) participants died. The main cause of death was CVD (14 participants, 8.6%), including stroke (nine participants), myocardial ischemia and infarction (three participants), and cardiac arrest (two participants). Other causes of death included pneumonia (one participants), poisoning (two participants), and unknown (seven participants).

For the total study population, the median age was 82.8 (81.3–85.1) years, the median MMSE score was 21 (19–23), and 17.9% of them were male. The median MMSE score for the 139 survivors was 21 (19–23), which is significantly higher than the corresponding score for the 24 nonsurvivors (19 [17–21], P=0.003).

The three MMSE groups were: MMSE ≥23 (n=54), MMSE 19–23 (n=60), and MMSE ≤19 (n=49). The baseline characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1. All-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were lowest in the group with top category of MMSE score and highest in the group with bottom category of MMSE score (all-cause mortality 5.6% vs 11.7% vs 28.6%, P=0.003; cardiovascular mortality 1.9% vs 8.3% vs 16.3%, P=0.002). The distribution of the three MMSE groups was comparable in age, body mass index, the percentage of current smokers, the percentage of treatment group, hemoglobin level, fasting glucose level, total cholesterol level, and serum creatinine level, with the exception of gender distribution (percentage of males 33.3% vs 8.3% vs 12.5%, P=0.001), the percentage of previous CVD (5.6% vs 1.7% vs 6.1%, P=0.05), and uric acid level (µmol/L, median 268 vs 231 vs 238, P=0.04).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of three MMSE groups

| Variables | MMSE ≥23 | MMSE 19–23 | P-value | MMSE ≤19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Number of participants | 54 | 60 | 49 | |

| Male, % | 33.3 (18) | 8.3 (5) | 12.5 (6) | 0.001 |

| Age, years | 82.8 (81.4–84.3) | 82.3 (80.9–84.3) | 83.5 (81.6–85.6) | 0.13 |

| Current smokers, % | 13.0 (7) | 8.3 (5) | 2.0 (1) | 0.11 |

| Previous CVD, % | 5.6 (3) | 1.7 (1) | 6.1 (3) | 0.05 |

| Treatment group, % | 37.0 (20) | 51.7 (31) | 55.1 (27) | 0.14 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.3 (21.1–23.5) | 22.2 (21.1–23.9) | 23.1 (22.5–23.9) | 0.06 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.0±1.4 | 12.0±1.2 | 11.7±1.4 | 0.44 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.8 (4.3–5.5) | 4.9 (4.2–5.6) | 4.9 (4.4–5.3) | 1.00 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.8±0.8 | 4.7±0.6 | 4.5±0.8 | 0.08 |

| Serum uric acid, µmol/L | 268 (220–313) | 231 (182–276) | 238 (196–284) | 0.04 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 175 (167–188) | 172 (163–182) | 174 (165–184) | 0.50 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 89 (79–93) | 88 (80–93) | 87 (77–93) | 0.87 |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L | 115 (102–130) | 115 (104–129) | 117 (106–128) | 0.95 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 48.9±6.3 | 46.3±6.9 | 46.4±7.0 | 0.08 |

| The MMSE score | 24 (23–26) | 21 (20–22) | 19 (18–19) | ,0.001 |

| All-cause mortality, % | 5.6 (3) | 11.7 (7) | 28.6 (14) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular mortality, % | 1.9 (1) | 8.3 (5) | 16.3 (8) | 0.002 |

Note: Data are presented as percentage (n) or mean ± SD or median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

The survival curves of three MMSE groups are shown in Figure 1. Cumulative survival rates were 94.4%, 86.3%, and 66.7% for the three MMSE groups (P=0.02). The group with the lowest category of MMSE score had the lowest cumulative survival rate.

Figure 1.

Survival curves of three MMSE groups (n=163).

Abbreviation: MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

Results of analyzing MMSE scores as a continuous variable are shown in Table 2. After making adjustment for potential confounders, every 1-point increase of the MMSE score was associated with 29% decreased risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58–0.87) and 39% decreased risk of cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44–0.83).

Table 2.

The MMSE score and mortality

| The MMSE score, every 1-score increase

|

||

|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | Cardiovascular mortality | |

|

| ||

| Crude HR | 0.76 (0.63–0.92) | 0.66 (0.50–0.88) |

| Age, gender adjusted HR | 0.75 (0.62–0.90) | 0.66 (0.50–0.97) |

| Multivariable adjusted HRa | 0.71 (0.58–0.87) | 0.61 (0.44–0.83) |

Notes: Data are presented as HR (95% CI).

Model was further adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, current smokers, previous CVD, treatment group, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, uric acid, diastolic BP, and eGFR.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rat; HR, hazard ratio; MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate Cox analyses of the three MMSE groups for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Compared with participants at the highest category of MMSE score, the adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among those with bottom category of MMSE score were 8.18 (95% CI, 2.05–32.54) and 14.72 (95% CI, 1.65–131.16).

Table 3.

Three MMSE groups and mortality

| MMSE 19–23 (n=119) | MMSE ≥23 (n=100) | MMSE ≤19 (n=65) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| All-cause mortality | |||

| Crude HR | Reference | 2.19 (0.57–8.37) | 4.72 (1.34–16.59) |

| Age, gender adjusted HR | Reference | 2.59 (0.63–10.61) | 5.92 (1.60–21.87) |

| Multivariable adjusted HRa | Reference | 3.30 (0.77–14.16) | 8.18 (2.05–32.54) |

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||

| Crude HR | Reference | 4.76 (0.56–40.77) | 9.01 (1.13–72.09) |

| Age, gender adjusted HR | Reference | 4.73 (0.52–42.75) | 10.39 (1.24–86.83) |

| Multivariable adjusted HRa | Reference | 6.55 (0.69–62.27) | 14.72 (1.65–131.16) |

Notes: Data are presented as HR (95% CI).

Model was further adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, current smokers, previous CVD, treatment group, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, uric acid, diastolic BP and eGFR.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rat; HR, hazard ratio; MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

Discussion

Our results, for the first time, indicated that the cognitive function assessed by MMSE score is independently associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among the very elderly population with predialysis CKD. These findings could assist the clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of mortality. Given the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in the very elderly with CKD, cognitive impairment might pose substantial risk as a contributing factor to mortality.

The association between cognitive impairment and mortality in the individuals with CKD has been recognized in recent decades. Griva et al12 firstly demonstrated a strong association between cognitive impairment and mortality in dialysis patients with an average age of 50.1±14.3 years. In addition, Raphael et al11 reported an association between cognitive impairment and mortality in people aged 60 years or older with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. However, participants in both the studies were much younger, and causes of death were not presented. There are also several studies investigating the association between cognitive impairment and mortality among the very elderly population. Gussekloo et al18 reported that mild cognitive impairment assessed with the MMSE score associated with a nearly two-fold increased risk of mortality in the very elderly aged 85 years or older. Takata et al19 found that cognitive impairment assessed with the MMSE score was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular mortality in the very elderly aged 85 years or older. Skoog et al20 reported that the MMSE score is associated with mortality even in individuals aged 97–100 years.20 However, baseline kidney function were not included in those studies, which has been recognized as the risk of both cognitive impairment and mortality,21,22 and therefore is a potential confounder. In the present study, we first explored the association between cognitive function and mortality among a very elderly population with CKD. Kidney function was evaluated at baseline and was included as a covariate in the regression analysis. Therefore, we demonstrated cognitive impairment was independent of kidney function contributing to the hazard risk of mortality among the very elderly population.

Several possible mechanisms may explain the association between cognitive impairment and mortality in the individuals with CKD. Both the kidney and brain share similar low-resistance vascular beds which are exposed to a high volume of blood flow.23 They also share common cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, hyperuricemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking, which may impair endothelial function mediated by inflammatory and oxidative processes.23 Impaired endothelial function is manifested as susceptibility to cognitive impairment in the brain and as impaired glomerular filtration and secondary proteinuria in the kidney.24,25 However, adjustments for kidney function and other established cardiovascular risks in this research, including smoking, previous CVD, fasting glucose level, uric acid level, cholesterol level, and blood pressure, did not attenuate the all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality risk associated with cognitive impairment. So, the association between cognitive impairment and mortality could not be fully explained by classical cardiovascular risk factors, and its potential underlying mechanisms still need to be further explored.

Another possible explanation is that even mild cognitive impairment has a significant and detrimental impact on treatment adherence,26 which is associated with mortality.27 Self-management for the CKD patients is important and complex, requiring themselves to remember, understand, and follow treatment advices accurately and modify unhealthy behaviors, especially in the very elderly. Cognitive impairment might result in suboptimal care because of difficulty in following treatment recommendations and managing multiple medications.26 Furthermore, cognitive impairment may be a surrogate marker of disease progression or global decline in health. Population-based studies have shown that general ill health is associated with cognitive impairment.28 It therefore is plausible that poor cognitive function in CKD patients is related to mortality because cognitive function is a sensitive indicator of general physical deterioration.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, information regarding the participants’ educational background and socioeconomic status was missing, which is significantly associated with cognitive function. However, the interquartile range of the MMSE score of all participants was relatively narrow (19–23), which might be a reflection of similar education background. Moreover, all participants were aged 80 years or older and were recruited from the same province of People’s Republic of China, and so we speculated that they might also have a similar socioeconomic background. Second, an optimal method for estimating kidney function among the very elderly has not been clearly established. Third, albuminuria has been suggested to correlate with cognitive decline and mortality. However, information regarding the participants’ urinalysis was missing. Fourth, our participants were not examined with imaging tests, which might reduce the accuracy to the evaluation of cognitive function. However, the MMSE also has good sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of cognitive function in the very elderly.29 Finally, the possibility of residual confounding exists, and we did not include a large number of participants, which might limit the statistical power of the analyses.

Despite these limitations, our study had several strengths. We explored the relationship between cognitive function and mortality among a very elderly population with CKD, which has not been investigated in previous studies. Other strengths also include the longitudinal design, confirmed and adjudicated death outcomes, and availability of many cardiovascular risk factors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our prospective study suggests that cognitive function assessed by MMSE score is associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the very elderly Chinese population with CKD. More attention should be paid to the evaluation and management of kidney function and cognitive function in the very elderly.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the grant from National Key Research and Development Program (no 2016YFC1305405), and a grant by the University of Michigan Health System and Peking University Health Sciences Center Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Giulioli C, Amieva H, Caroline G, Helene A. Epidemiology of Cognitive Aging in the Oldest Old. Rev Invest Clin. 2016;68(1):33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maw TT, Fried L. Chronic kidney disease in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(3):611–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowling CB, Inker LA, Gutiérrez OM, et al. Age-specific associations of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate with concurrent chronic kidney disease complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(12):2822–2828. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06770711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowling CB, Muntner P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease among older adults: a focus on the oldest old. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(12):1379–1386. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed FA. Kidney Disease in Elderly: Importance of Collaboration between Geriatrics and Nephrology. Aging Dis. 2018;9(4):745–747. doi: 10.14336/AD.2018.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zammit AR, Katz MJ, Bitzer M, Lipton RB. Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Older Adults With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30(4):357–366. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai K, Pan Y, Lu F, Zhao Y, Wang J, Zhang L. Kidney function and cognitive decline in an oldest-old Chinese population. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1049–1054. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S134205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang F, Zhang L, Liu L, Wang H. Level of kidney function correlates with cognitive decline. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32(2):117–121. doi: 10.1159/000315618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger I, Wu S, Masson P, et al. Cognition in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Fried LF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2127–2133. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raphael KL, Wei G, Greene T, Baird BC, Beddhu S. Cognitive function and the risk of death in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(1):49–57. doi: 10.1159/000334872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griva K, Stygall J, Hankins M, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP. Cognitive impairment and 7-year mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(4):693–703. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckett NS, Peters R, et al. HYVET Study Group Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulpitt C, Fletcher A, Beckett N, et al. Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET): protocol for the main trial. Drugs Aging. 2001;18(3):151–164. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma YC, Zuo L, Chen JH, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2937–2944. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters R, Beckett N, Fagard R, et al. Increased pulse pressure linked to dementia: further results from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial – HYVET. J Hypertens. 2013;31(9):1868–1875. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283622cc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Remarque EJ, Lagaay AM, Heeren TJ, Knook DL. Impact of mild cognitive impairment on survival in very elderly people: cohort study. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1053–1054. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takata Y, Ansai T, Soh I, et al. Cognitive function and 10 year mortality in an 85 year-old community-dwelling population. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1691–1699. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S64107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skoog J, Backman K, Ribbe M, et al. A Longitudinal Study of the Mini-Mental State Examination in Late Nonagenarians and Its Relationship with Dementia, Mortality, and Education. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1296–1300. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5):1307–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000123691.46138.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried LF, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Kidney function as a predictor of noncardiovascular mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(12):3728–3735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogi M, Horiuchi M. Clinical Interaction between Brain and Kidney in Small Vessel Disease. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:306189. doi: 10.4061/2011/306189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Rourke MF, Safar ME. Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney: cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension. 2005;46(1):200–204. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168052.00426.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray AM. The brain and the kidney connection: A model of accelerated vascular cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2009;73(12):916–917. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b99a2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes TL, Larimer N, Adami A, Kaye JA. Medication adherence in healthy elders: small cognitive changes make a big difference. J Aging Health. 2009;21(4):567–580. doi: 10.1177/0898264309332836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tilvis RS, Kähönen-Väre MH, Jolkkonen J, Valvanne J, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE. Predictors of cognitive decline and mortality of aged people over a 10-year period. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):M268–M274. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahle-Wrobleski K, Corrada MM, Li B, Kawas CH. Sensitivity and specificity of the mini-mental state examination for identifying dementia in the oldest-old: the 90+ study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]