Abstract

Background:

Stressful or supportive social environments promote biological changes with regulatory implications for future relationships and substance abuse. Recent research suggests links between adverse social environments, prosocial relationships, methylation at the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR), and substance abuse. The potential for OXTR methylation to act as the mechanism linking social environments to substance abuse has yet to be investigated. We hypothesized that, for young African American men, childhood adversity increases, and supportive, prosocial bonds with parents, peers, partners, and community mentors decrease OXTR methylation levels, which in turn predict increases in substance-related symptoms.

Methods:

A sample of 358 rural African American men (age 19 at baseline) provided self-report data at three time points separated by 18 months and a genetic specimen at Time 2.

Results:

Early adversity was associated with OXTR methylation indirectly via contemporary prosocial relationships. OXTR methylation was a proximal predictor of changes in substance-related symptoms. We found no evidence for a direct association of self-reported childhood trauma with OXTR methylation status.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that OXTR methylation is linked to substance use symptomatology, ostensibly resulting in increased expression of oxytocin (OT) in peripheral and central nervous systems. OXTR may act as a mechanism to explain how prosocial ties deter substance abuse and related problems. Despite conjectures in the literature that early adversity may become physiologically embedded via methylation in the OT system, direct effects were not evident. Rather, early adversity may affect OXTR methylation via influence on contemporary prosocial relationships.

Keywords: African American men, DNA, life stress, oxytocin, social environment, substance abuse

1. Introduction

Substance use peaks during the young adult years; a majority of people ages 18–24 will misuse alcohol or report the use of marijuana or other illicit drugs during this period (Johnston et al., 2015). The vast majority of young people, however, will not develop substance-related problems (Nelson et al., 2015). The factors that differentiate those who experience serious consequences from those whose use has relatively slight long-term impact remain poorly understood. This question is particularly germane for African American men from low socioeconomic status (SES) environments. The decade after high school is a unique developmental turning point for substance-related problems among African American men (Watt, 2008). Use is generaly low during adolescence, with steep increases during young adulthood. Studies indicate that African American men experience more negative consequences per ounce of substances consumed than do their White peers, including substance-related injuries (Keyes et al., 2012), social, legal, and work difficulties (Mulia et al., 2009; Zapolski et al., 2014), and risk for substance use disorders (SUDs; Caetano et al., 2013; Mulia et al., 2009). These findings underscore the utility of investigating young adult SUD symptoms within this population.

Considerable evidence points to the influence of social relationships, both contemporary and in the rearing environment, on vulnerability to substance use and related consequences. Studies with animal models document the role of contextual stressors, such as early adversity, social defeat, subordination, and a lack of resources, in accelerating the progression from onset to problem use (Bardo et al., 2013). Similarly, among adult substance abusers, social relationship quality predicts patterns of escalation and desistance, as well as variability in rates of relapse and recovery after treatment (Goeders, 2003). Emerging research suggests that exposure to early adversity and stressors in the social environment may contribute to the escalation of substance use among vulnerable young adults in general (Sinha, 2008), and low-SES African American men in particular (Kogan et al., 2017b). These men are differentially exposed to adverse childhood experiences, which affect downstream relationships that comprise proximal predictors of substance use escalation and consequences (Umberson et al., 2014). Conversely, economic and race-related challenges to the establishment of prosocial relationships in young adulthood undermine the process of “maturing out” of substance use observed near the end of the young adult transition (Kogan et al., 2017a).

Exposure to stressful or salubrious social environments promotes numerous biological changes, some with direct regulatory implications for future relationships and substance use. Informed by evidence of common mechanisms linking social relationships, stress response, and addiction (Ozbay et al., 2007), recent research has focused on oxytocin (OT), a neuroactive peptide. OT is secreted mainly into the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland; it binds to a G protein-coupled receptor (OTR) that is expressed widely in the central nervous system. OT is thought to increase interpersonal trust, reduce stress responses, and increase resilience while protecting against drug addiction (MacDonald and MacDonald, 2010). Intranasal administration of OT can prevent tolerance to ethanol and opiates, reduce the induction of hyperactive behavior by stimulants, and diminish withdrawal symptoms from sudden abstinence from alcohol and other drugs (Graustella and MacLeod, 2012). The OT system also has been implicated in social cognition, stress, and addiction at the genetic level: allelic variation in the rs53576 variant in intron 3 of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is associated with increases in empathy, optimism, and trust, as well as with risk for substance use and abuse in adolescents and adults (Vaht et al., 2016).

Recent studies have suggested that epigenetic modification of OXTR may be a mechanism whereby experiences in social environments become biologically embedded, predisposing or protecting individuals from the negative influences of substance use (Alves et al., 2015; Cecil et al., 2014; Tops et al., 2014). OXTR contains a CpG island spanning exons 1 to 3 (Chr3:8 808 962–8 811 280, GRCh37/hg19; Kumsta et al., 2013), with evidence indicating that increased OXTR methylation is associated with decreased OXTR expression, leading to behavioral effects. Methylation of the cytosine pyrimidine ring in CpG dinucleotides occurs in response to environmental factors, including adverse rearing environments associated with maladjustment in attachment systems and the inability to develop supportive, close relationships (Alves et al., 2015). OXTR methylation has been shown to increase in response to maltreatment (Cecil et al., 2014; Unternaehrer et al., 2015), and conflicted or unsupportive social relationships (Simons et al., 2016).

The OT system is associated in complex ways with attachment processes, social cognition, and individuals’ resilience to stressful circumstances (Cochran et al., 2013). Recent reviews (Tops et al., 2014) suggest that the OT system is designed to shift neurocognitive processes from seeking novelty and rewards to reinforcing familiarity. As individuals form social bonds based on routine interaction, internal working models of relationship dynamics affect emotion and behavior regulation. This may explain why secure attachments are associated with increased resilience and less reactive reward responding in the presence of stress. A well-regulated stress response appears to play a critical proximal role in the consequences of substance use (Sinha, 2008). Recent prospective research with adults linked adverse social environments and methylation at OXTR to cognitive schemas associated with attachment style (Simons et al., 2016), internalizing problems (Gouin et al., 2017), and autistic traits (Rijlaarsdam et al., 2017). The potential for OXTR methylation to act as mechanism linking social environments to substance abuse problems has yet to be investigated.

In the present study, we tested hypotheses regarding the influences of adversity in childhood and nurturing prosocial relationships in adulthood on substance abuse symptomatology via their associations with OXTR methylation. We hypothesized that, for young African American men, childhood adversity and supportive, prosocial bonds with parents, peers, partners, and community mentors would contribute independently to OXTR methylation levels, which would predict increases in substance-related symptoms during young adulthood. Although the majority of extant studies of OXTR methylation depend on modest-sized samples (<100), advances in obtaining methylation data from saliva facilitate the assessment OXTR methylation in well-characterized and sufficiently powered longitudinal studies (Smith et al., 2015). Specifically, hypotheses were tested with data from 358 frican American young men from resource-poor rural environments who participated in a longitudinal study of substance use and risky behavior.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

At the baseline interview, participants included 505 African American men who resided in one of 11 rural counties in South Georgia, an area representative of a geographic concentration of rural poverty across the southern coastal plain (Crockett et al., 2016). Men were 19 to 22 years of age (M = 20.22; SD = 1.09) at the baseline interview (Time 1; T1). Participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling (RDS), which combines a prescribed chain-referral recruitment method designed to reduce biases commonly associated with network-based samples (Heckathorn, 1997). Community liaisons recruited 45 initial seed participants from targeted counties to complete a baseline survey. Each participant was then asked to identify three other men in his community from his personal network who met the criteria for inclusion in the study (African American, age 19–22, and living in the targeted area). Project staff contacted the referred potential participants, and the referring participant received $25 per person who completed the survey. After completing the survey, each referred participant was asked to refer three men in his network. The RDS protocols and weighting system are designed to attenuate the influence of biases common in chain-referral samples and to improve approximation of a random sample of the target population (Heckathorn, 1997, 2002). Analyses of network data related to substance use and other risky behavior at T1 (Kogan et al., 2016) indicated that the sample evinced negligible levels of common biases observed in chain-referral samples arising from the characteristics of the initial seed participants, the recruitment efficacy of individual participants, and differences in the sizes of participants’ networks.

Approximately 18.30 (SD = 4.19) months after the baseline survey, when men’s mean age was 21.85 years (SD = 1.27), a follow-up data collection visit (Time 2; T2) was conducted in the same manner. third visit (Time 3; T3) took place 19.68 months after T2; men’s mean age at T3 was 23.12 (SD = 1.26). Of the 505 men who participated at T1, 423 (84%) completed the T2 survey and 409 (81%) completed the T3 survey. Retention status was not associated with any study variables (p-values > .21). At T2, participants provided DNA specimens. Of the 423 participants who completed survey data at T2, 374 (88.4%) agreed to provide a specimen, and 358 (95.7%) had valid information on their OXTR methylation. Analyses comparing those who declined to provide a specimen and those who provided one revealed no differences on demographic (income, age, student status) or other study variables (childhood trauma, social ties, substance-related problems).

2.2. Procedures and measures

African American research staff visited participants in their homes or at convenient community locations, where participants completed an audio computer-assisted self-interview on a laptop computer. This allowed participants to navigate the survey privately with the help of voice and video enhancements, eliminating literacy concerns. Participants received $100 at each time point for completing the surveys. Participants provided written informed consent, and all study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the niversity at which the study was conducted. At T2, participants provided DNA specimens using Oragene Discover OGR-500 kits (DNA Genotek Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada). Participants rinsed their mouths with tap water and then deposited 2 ml of saliva in the Oragene sample vial. The vial was sealed, inverted, and shipped via courier to a central laboratory in Iowa City, Iowa, where samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

2.2.1. OXTR methylation assays.

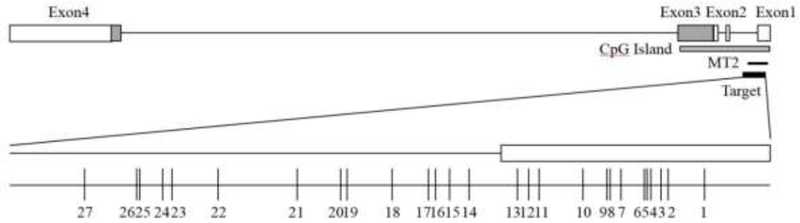

DNA was extracted using prepIT®•L2P reagent (DNA Genotek) and was quantified with PicoGreen® (Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Five hundred ng of DNA was treated with bisulfite using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). DNA methylation of 27 CpG sites (see Figure 1) in the promoter region including the MT2 region (Kusui et al., 2001) of the OXTR gene (chr3: 8,792,095–8,811,300; hg19 build) were analyzed using EpiTYPER (MassARRAY system; Agena Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forward (aggaagagagGAGGTTTTAGTGAGAGATTTTAGTTTAG) and reverse (cagtaatacgactcactatagggagaaggctTCCCTACTAAAAAAACCCCTACCTC) primers were used corresponding to chr3: 8,810,604 – 8,811,075 (Clark and Coolen, 2007); see Figure 1. Cycling conditions were: denaturation (94°C for 15 min), then 50 cycles of amplification (94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 30 s) and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. Samples were electrophoresed using 2% agarose gel to confirm amplification.

Figure 1.

Overview of OXTR and methylation sites

Note: Gene structure of OXTR (chr3: 8,792,095–8,811,300; hg19). MT2 (chr3: 8761543–8761138; Kusui et al., 2001). The location of 27 CpG sites in this study are indicated below. Assayed CpG sites correspond to the following genomic positions: chr3: 8811028 (CpG1), chr3: 8811010/8811005 (CpG2,3), chr3: 8810999 (CpG4), chr3: 8810995/8810993 (CpG5,6), chr3: 8810981 (CpG7), chr3: 8810974/8810971 (CpG8,9), chr3: 8810958 (CpG10), 8810936/8810930 (CpG11,12), chr3: 8810924 (CpG13), chr3: 8810890 (CpG14), chr3: 8810875 (CpG15), chr3: 8810863 (CpG16), chr3: 8810856 (CpG17), chr3: 8810833 (CpG18), chr3: 8810808/8810798 (CpG19,20), chr3: 8810775 (CpG21), chr3: 8810734 (CpG22), chr3: 8810709 (CpG23), chr3: 8810700 (CpG24), chr3: 8810682/8810680 (CpG25,26), chr3: 8810648 (CpG27)

Mass spectra methylation ratios were generated using EpiTYPER version 1.2 (Agena Biosciences). The instrument detects 16 Da molecular weight differences between methylated and unmethylated fragments. The percentages (or rates) of the surface area of the peak representing the methylated fragments are calculated as follows: methylation rate = methylated fragment / methylation fragment + unmethylated fragment {Suchiman, 2015 #13266}. The reliability of the methylation assays was checked for each CpG site. Epitect control DNA samples (Qiagen) known to be fully methylated and fully unmethylated were assessed in parallel to the study DNA to determine the upper and lower limits of detection for each assay.

2.2.2. OXTR DNA methylation index.

Previous research has evaluated methylation at individual CpG sites as well as mean methylation levels across sites in this region (Dadds et al., 2014; Szyf and Bick, 2013). Consistent with prior research (Dadds et al., 2014), the present study used an index summing 13 consecutive CpG sites across chr3: 8810890 (CpG14) to chr3: 8810682/8810680 (CpG25,26). Prior to summing these sites, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to determine if a unidimensional index of methylation was appropriate. Specifying each site as loading on a single factor resulted in the following fit to the data: χ2 (37) = 66.36, p < .01, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .04, and SRMR = .04. All sites loaded significantly on a single factor with loadings ranging from .28 to .56, suggesting that summing individual loci was appropriate.

2.2.3. Substance use-related problems.

At T1 and T3, men used a 9-item scale to report the number of substance use-related problems they experienced during the past three months. Items indexed the frequency with which the use of “alcohol or drugs” led to a range of difficulties that included problems with family, missing work, driving vehicles while intoxicated, and substance-related legal problems. Possible responses were 0 (0 days), 1 (1 day), 2 (2 days), 3 (3 days), 4 (4–6 days), 5 (7–10 days), and 6 (11 or more days). Responses were dichotomized to indicate the presence (1) or absence (0) of the problem then summed to form the substance use problems measure. Cronbach’s alphas were.86 at T1 and .92 at T3.

2.2.4. Prosocial ties.

Consistent with research suggesting that the number of social bonds with parents, romantic partners, mentors, and peers has a more robust influence on substance use than do any particular relationships (Epstein et al., 2001; Sullivan and Farrell, 1999), we developed a prosocial ties index with scales obtained at Waves 1 and 2. Instrumental and emotional support received from and given to a main romantic partner (“a woman or girl that you have a very special or committed romantic or sexual relationship with, such as a girlfriend or a spouse”) and the primary parent (“the person who raised you”) were assessed with the etwork of Relationships Inventory Support Scale for a main romantic partner (7 items; alphas = .79 at T1 and .85 at T2) and for a primary parent (9 items; alphas = .87 at T1 and .92 at T2). Because peers’ low levels of antisocial behavior is closely associated with supportive peer relationships, we assessed this behavior with an 11-item survey (alphas = .90 at T1 and .92 at T2). The measures for the three forms of social ties (parents, peers, partners) were dichotomized based on a median split and scored as 0 = positive bond not present or 1 = positive bond present, and they were summed to create the cumulative index of prosocial ties (range = 0–3). The mean numbers of prosocial ties were 1.21 (SD = 0.87) at T1 and 1.22 (SD = 0.89) at T2.

2.2.5. Childhood adversity.

At T3, men completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF; (Bernstein et al., 1997). The CTQ-SF contains 28 items that assess sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect experienced prior to the age of 16. The response scale ranged from 0 (never true) to 5 (very often true). Items were summed to index childhood adversity; alpha for the total score was .90.

2.2.6. Demographic covariates.

Demographic covariates at baseline were assessed to consider their potential confounding effects. Age was assessed as a continuous variable. Young men also reported their enrollment in school or any type of educational program; responses were coded as 0 (enrolled; 50.3%) or 1 (not enrolled; 49.7%). Employment status was assessed using the item, “Are you currently employed?” The responses were coded as 0 (yes; 41.1%) or 1 (no; 58.9%). Economic distress was assessed with a 5-item scale. Young men reported, on a response set ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), whether they had enough money during the past 3 months for shelter, food, clothing, and medical care (α = .79).

2.3. Plan of analysis

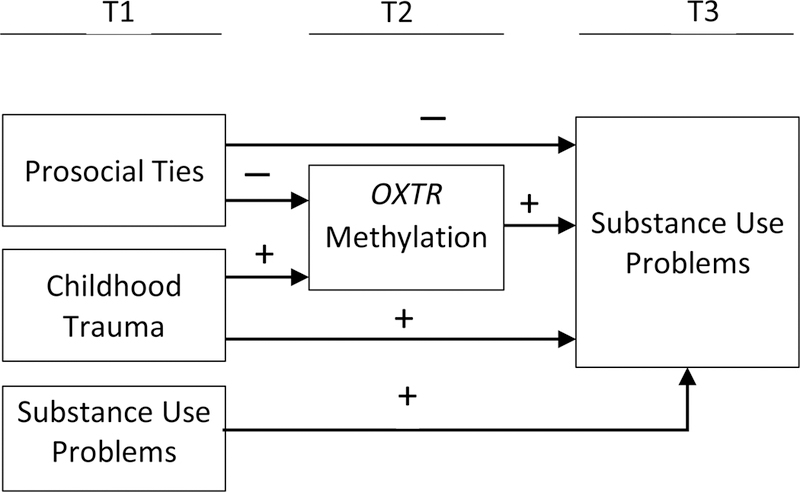

Hypotheses were tested with path analyses using the maximum likelihood estimator as implemented in Mplus 7.13 (Muthén and uthén, 1998–2015). Parameters were estimated and missing data were managed with full information likelihood estimation (FIML). The analytic sample comprised 358 cases for which we had valid OXTR methylation data. The FIML estimator tests hypotheses with all available data; no cases are dropped. The model was estimated in the presence of data missing due to (a) attrition across follow-up assessments (38 cases, 10.6%) and (b) item non-response (0 – 2 cases, 0.0 – 0.6%). To assess goodness of fit, we used indices that Bollen (Bollen, 1989) recommended. Figure 3 presents the model specification for the initial path analysis controlling for participants’ sociodemographic covariates (e.g., age, employment status). The significance of indirect effects was assessed with bootstrapping, and effect sizes were calculated based on the proportion of indirect effects to the total effects using a protocol of a regression-based model (Preacher and Kelley, 2011).

Figure 3.

Model Specification and Hypothesized Effects

3. Results

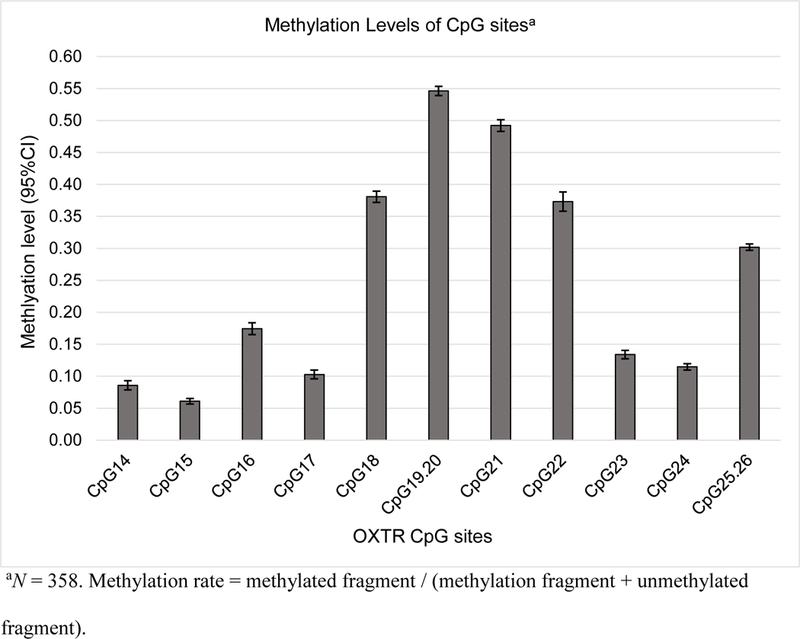

Figure 2 presents mean levels of methylation for each of the 13 CpG sites in the index, and mean levels of methylation at each quartile of prosocial ties. The methylation rates (methylated fragment / [methylation fragment + unmethylated fragment]) ranged from 6% to 55% across 14 CpG sites, and the average methylation rate was 25%. Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among the study variables. The mean numbers of substance use problems were 1.11 at T1 and 2.87 at T3, which indicated a significantly higher number of substance use-related problems among this sample at age 23 than at age 20 (p < .01).

Figure 2.

Methylation levels of each OXTR CpG site

Table 2.

Path analysis of direct and indirect OXTR methylation effects and substance use problems

|

Model 1. Childhood Trauma, Prosocial Ties (W1) → OXTR Methylation (W2) → Substance Use Problems (W3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Mediator (W2) | β (95%CI) | p | |

| Childhood Trauma | → | OXTR Methylation (W2) | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.06) | .36 |

| Prosocial Ties (W1) | → | OXTR Methylation (W2) | −0.15 (−0.25, −0.05) | .004 |

| Predictors | Outcome (W3) | β (95%C ) | p | |

| Substance Use Problems (W1) | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | 0.09 (0.01, 0.20) | .04 |

| Childhood Trauma | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | 0.19 (0.07, 0.33) | <.001 |

| Prosocial Ties (W1) | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | −0.15 (−0.28, −0.02) | .03 |

| OXTR Methylation (W2) | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | 0.20 (0.05, 0.36) | .008 |

|

Model 2. Childhood Trauma → Prosocial Ties (W2) → OXTR Methylation (W2) → Substance Use Problems (W3) | ||||

| Predictors | Mediator (W2) | β (95% CI) | p | |

| Prosocial Ties (W1) | → | Prosocial Ties (W2) | 0.28 (0.19, 0.38) | <.001 |

| Childhood Trauma | → | Prosocial Ties (W2) | −0.28 (−0.40, −0.17) | <.001 |

| Prosocial Ties (W2) | → | OXTR ethylation (W2) | −0.12 (−0.22, −0.02) | .03 |

| Predictors | Outcome (W3) | β (95%CI) | p | |

| Substance Use Problems (W1) | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | 0.11 (0.02, 0.21) | .03 |

| Childhood Trauma | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | 0.22 (0.13, 0.35) | <.001 |

| Prosocial Ties (W1) | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | −0.03 (−0.23, 0.17) | .79 |

| OXTR Methylation (W2) | → | Substance Use Problems (W3) | 0.21 (0.05, 0.37) | .007 |

Note. N = 358. Model 1 (χ2 = 12.10, df = 11, p = .36. RMSEA = .02. CFI = .96). Model 2 (χ2 = 17.86, df = 21, p = .65. RMSEA = .01. CFI = .99) In Model 1 and Model 2, target age, school enrollment status, employment status, and economic distress at baseline were controlled. CI = confidence interval.

The model, presented in Table 2, fit the data closely: χ2 = 12.10, df = 11, p = .36, RMSEA = .02. CFI = .96. Prosocial ties at T1 evinced a significant association with OXTR methylation at T2 (β [95%CI] = −.15 [−0.025, −0.05], p < .01). Childhood trauma as assessed with the CTQ was not associated with OXTR methylation. OXTR methylation at T2 was positively associated with substance use problems at T3 (β [95%CI] = .20 [0.05, 0.36], p < .01). Both prosocial ties and childhood trauma evinced significant direct effects on substance use problems at T3. The indirect effect of prosocial ties on substance use problems via OXTR methylation was significant (b [95%CI] = −.03, [−0.077, −0.003], effect size = .20).

The lack of a hypothesized association between childhood trauma and OXTR methylation sponsored an auxiliary analysis. Because research indicates that methylation levels may be modulated not only by childhood experiences, but also by ongoing social interactions (Unternaehrer et al., 2012), we hypothesized that childhood trauma may be a distal influence that carries forward through more proximal social ties. In this case, the influence of childhood trauma on OXTR methylation would primarily be a function of its influence on contemporary prosocial ties. We leveraged our repeated measures design to test the hypothesis that childhood trauma would predict changes in prosocial ties from T1 to T2, thus predicting OXTR methylation status.

The results of Model 2 are presented in Table 2. The data fit the model as follows: χ2 = 17.86, df = 21, p = .65, RMSEA = .01. CFI = .99. As hypothesized, childhood trauma was significantly associated with changes in prosocial ties (β [95%CI] = −.28 [−0.40, −0.17], p < .01) from T1 to T2, which was a proximal predictor of OXTR methylation (β [95%CI] = −.12 [−0.22, - 0.02], p < .05). Significant indirect effect of childhood trauma on OXTR methylation via prosocial ties were detected (b = .04, 95% CI [0.003, 0.078], effect size = .37). Levels of OXTR methylation were positively associated with substance use problems at T3 (β [95%CI] = .21 [0.05, 0.37], p < .01), after controlling for the effects of childhood trauma (β [95%CI] = .22 [0.13, 0.35], p < .01) and prosocial ties (β [95% CI] = −.03 [−0.23, 0.17], p = .79). The indirect effect of prosocial ties on substance use problems via OXTR methylation was significant (b [95% CI] = −.03 [−0.054, −0.002], effect size = .34). Finally, our hypothesized indirect paths linking childhood trauma to substance use problems via prosocial ties and OXTR methylation was significant (b [95% CI] = .01 [0.001, 0.020], effect size = .12).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the potential role of methylation in OXTR as a mediator linking childhood trauma and prosocial ties in young adulthood to changes in substance use problems among young African American men. Consistent with our hypotheses, OXTR methylation was a proximal predictor of changes in substance use disorder symptomatology during a three-year period. Despite some previous evidence that early adversity may become physiologically embedded via methylation in the OT system (Alves et al., 2015), we found no evidence for a direct association of self-reported childhood trauma with OXTR methylation status. Rather, more contemporary prosocial relationships were associated with reduced methylation, ostensibly resulting in increased expression of OT in peripheral and central nervous systems (Kusui et al., 2001). Follow-up analyses suggest that the influence of early adversity may affect OXTR methylation by undermining downstream prosocial relationships.

Accumulating evidence suggests that aspects of the OT system may protect against substance use symptoms, modulating the rewarding effects of drugs and supporting social relationships that deter substance abuse (Tops et al., 2014). Consistent with this speculation, we found that methylation at OXTR forecasts increases in substance use disorder symptoms. This effect was independent of the influence of childhood trauma and prosocial ties in young adulthood. An independent effect with these variables controlled suggests that OXTR expression may operate directly on the relative reward value of substances compared with supportive relationships that provide external sources of control on substance-related behaviors. Tops et al. (2014) speculate that OT affects substance-related problems by countering processes associated with novelty seeking and increasing the salience and reward reinforcement of social interactions. These findings also are consistent with intranasal administration studies in which OT reduced cravings and distress among substance-dependent participants (McGregor and Bowen, 2012).

Changes in prosocial ties over a span of 18 months predicted OXTR methylation. This finding is consistent with recent research by Simons et al. (2016) linking stressful social and economic environments to OXTR methylation among African American adults. Similarly, research links aspects of conflict and support in spousal and other close relationships to circulating OT levels, generally finding that supportive relationships are associated with increases in OT production (Unternaehrer et al., 2012). In contrast, despite a robust negative direct effect on substance use, childhood trauma did not predict methylation status. Preclinical studies find that harsh parenting is transmitted across generations through methylation at OXTR (Alves et al., 2015). To date, clinical studies linking aspects of adversity to OT or OXTR methylation are inconsistent (Alves et al., 2015). Findings from the present study suggest that, rather than exerting a direct effect on methylation, childhood trauma and other forms of adversity may contribute to problems with establishing and maintaining salutary relationships, which in turn affect methylation status. Support for this thesis is evident in research indicating that OXTR methylation can fluctuate in response to day-to-day social interactions (Unternaehrer et al., 2012). Alternatively, one study found that OXTR methylation moderated the influence of a history of physical abuse (Smearman et al., 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that OXTR methylation may act as a vulnerability factor, increasing the impact of stressful experiences and negative relationships.

Indirect effects analyses suggest that OXTR methylation is a mediator of the influence of prosocial ties on substance-related problems. Among young adults, social ties play critical roles in the diminution of “normative” substance abuse observed during the transition to adulthood. The present study suggests that the protective effects observed when young adults maintain prosocial bonds may operate by decreasing OXTR methylation and thereby increasing OXTR expression. Such activity supports continued relationship development and may counteract the rewarding effects of alcohol and some drugs.

Caution is necessary in interpreting this study’s findings. Childhood trauma was retrospectively self-reported and may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. OXTR methylation was assayed using DNA from saliva samples. Validation of this procedure and concordance with sera-based methods suggests that this procedure yields reliable information on OXTR methylation in both central and peripheral systems. Cellular heterogeneity can represent a confounding factor for epigenetic studies of saliva-derived DNA. However, the MT2 region of OXTR is located in a CpG island which has consistently low levels of methylation among cell types that express OXTR (Smith et al., 2015). This feature minimizes the impact of differences in cell type for between-group comparisons. Though based on prior findings, the OXTR methylation index had modest reliability. This increases the potential for Type II errors and may lead to underestimation of the effect of methylation. The potential links between circulating OT and OXTR methylation are unclear; studies that include assessment of methylation as well as and circulating levels of OT are warranted. In addition, some participants were relatives of each other (e.g., cousins, nephews); the extent to which shared genetic variance affected findings is not known. Finally, OXTR data were available at only one time point. Future studies with repeated assessments of OXTR methylation are needed to identify more clearly directions of effect among substance use symptoms, social relationships, and methylation.

5. Conclusion

Our findings provide evidence that OXTR methylation is linked to substance use symptomatology and may act as a mechanism to explain how prosocial ties deter substance abuse and related problems. We also found support for a perspective on childhood trauma as an instigator of poor relationships that affect OXTR expression downstream, rather than a stable effect that is biologically embedded during childhood.

Table 1.

Correlations among the study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (T1) | – | |||||||||

| 2. School enrollment statu (T1) |

−.26** | – | ||||||||

| 3. Employment status (T1) | .03 | −.03 | – | |||||||

| 4. Economic distress (T1) | .09 | −.08 | .01 | – | ||||||

| 5. CTQ (retrospective) | .04 | −.13** | −.11* | .07 | – | |||||

| 6. Prosocial ties (T1) | −.11* | .07 | −.02 | −.05 | −.15** | – | ||||

| 7. Prosocial ties (T2) | −.02 | .08 | .06 | −.06 | −.32** | .31** | – | |||

| 8. OXTR methylation (T2 | .02 | .03 | −.09 | .03 | −.02 | −.14** | −.11* | – | ||

| 9. Substance use problems (T1) |

.14** | −.03 | .03 | .08 | .03 | −.11** | −.01 | .02 | – | |

| 10. Substance use problems (T3) |

.08 | .01 | .06 | .15** | .23** | −.24** | −.18** | .26** | .15* | – |

| Mean | 20.22 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 10.56 | 24.16 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 0.25 | 1.11 | 2.87 |

| SD | 1.09 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 3.10 | 14.25 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 1.96 | 2.54 |

Note.p < .05

p < .01.

Highlights.

Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) methylation predicts substance use problems among young African American men.

OXTR methylation predicts fewer supportive prosocial ties among African American men.

Prosocial ties may deter substance use problems via reductions in OXTR methylation.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by Grants R01 DA029488 and P30 DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We would like to thank Eileen Neubaum-Carlan, MS, for her editorial assistance.

Author Disclosures

Role of the Funding Source

Nothing declared

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alves E, Fielder A, Ghabriel N, Sawyer M, Buisman-Pijlman FTA, 2015. Early social environment affects the endogenous oxytocin system: A review and future directions. Front. Endocrinol 6, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo M, Neisewander J, Kelly T, 2013. Individual differences and social influences on the neurobehavioral pharmacology of abused drugs. Pharmacolog. Rev 65, 255–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L, 1997. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, 1989. Structural equations with latent variables Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Vaeth P, Chartier KG, Mills BA, 2013. Epidemiology of drinking, alcohol use disorders, and related problems in US ethnic minority groups. Handbook Clin. Neurol 125, 629–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil CAM, Lysenko LJ, Jaffee SR, Pingault J-B, Smith RG, Relton CL, Woodward G, McArdle W, Mill J, Barker ED, 2014. Environmental risk, Oxytocin Receptor Gene (OXTR) methylation and youth callous-unemotional traits: A 13-year longitudinal study. Molec. sychiatry 19, 1071–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Coolen M, 2007. Genomic profiling of CpG methylation and allelic specificity using quantitative high-throughput mass spectrometry: Critical evaluation and improvements. Nucleic Acids Res 35, e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran D, Fallon D, Hill M, Frazier JA, 2013. The role of oxytocin in psychiatric disorders: A review of biological and therapeutic research findings. Harv. Rev. psychiatry 21, 219–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Carlo G, Temmen C, 2016. Ethnic and racial minority youth in the rural United States: An overview, rural ethnic minority youth and families in the United States Springer, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Moul C, Cauchi A, Dobson-Stone C, Hawes DJ, Brennan J, Ebstein RE, 2014. Methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene and oxytocin blood levels in the development of psychopathy. Devel. Psychopathol 26, 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, 2001. Protective factors buffer effects of risk factors on alcohol use among inner-city youth. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse 11, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, 2003. The impact of stress on addiction. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 13, 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin JP, Zhou QQ, Booij L, Boivin M, Cote SM, Hebert M, Ouellet-Morin I, Szyf M, Tremblay RE, Turecki G, Vitaro F, 2017. Associations among oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) DNA methylation in adulthood, exposure to early life adversity, and childhood trajectories of anxiousness. Sci. Rep 7, 7446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graustella AJ, MacLeod C, 2012. A critical review of the influence of oxytocin nasal spray on social cognition in humans: Evidence and future directions. Horm. Behav 61, 410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD, 1997. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc. Problems 44, 174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD, 2002. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc. Problems 49, 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA, 2015. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–55 . Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Liu XC, Cerda M, 2012. The role of race/ethnicity in alcohol-attributable injury in the United States. Epidemiol. Rev 34, 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Cho J, Barton AW, Duprey EB,Hicks MR,Brown GL,2016The influence of community disadvantage and masculinity ideology on number of sexual partners: A prospective analysis of young adult, rural black men. J. Sex. Res 54, 795–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Cho J, Brody GH, Beach SRH, 2017a. Pathways linking marijuana use to substance use problems among emerging adults: A prospective analysis of young Black men. Addict. Behav 72, 86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Cho J, Oshri A, MacKillop J, 2017b. The influence of substance use on depressive symptoms among young adult black men: The sensitizing effect of early adversity. Am. J. Addict 26, 400–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta R, Hummel E, Chen FS, Heinrichs M, 2013. Epigenetic regulation of the oxytocin receptor gene: Implications for behavioral neuroscience. Front. Neurosci 7, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusui C, Kimura T, Ogita K, Nakamura H, Matsumura Y, Koyama M, Azuma C, Murata Y, 2001. DNA methylation of the human oxytocin receptor gene promoter regulates tissue-specific gene suppression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm 289, 681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K, MacDonald TM, 2010. The peptide that binds: A systematic review of oxytocin and its prosocial effects in humans. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 18, 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor IS, Bowen MT, 2012. Breaking the loop: Oxytocin as a potential treatment for drug addiction. Horm. Behav 61, 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE, 2009. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 33, 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 1998–2015. Mplus user’s guide, 7th ed. Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SE, Van Ryzin MJ, Dishion TJ, 2015Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use trajectories from age 12 to 24 years: Demographic correlates and young adult substance use problems. Dev. Psychopathol 27, 253–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA III, Charney D, Southwick S, 2007. Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry 4, 35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K, 2011. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psycholog. Methods 16, 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijlaarsdam J, van IMH, Verhulst FC, Jaddoe VW, Felix JF, Tiemeier H, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, 2017. Prenatal stress exposure, oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) methylation, and child autistic traits: The moderating role of OXTR rs53576 genotype. Autism Res 10, 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lei MK, Beach SRH, Cutrona CE, Philibert RA, 2016. Methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene mediates the effect of adversity on negative schemas and depression. Dev. Psychopathol 29, 725–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, 2008. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals N. Y. Acad. Sci 1141, 105–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smearman EL, Winiarski DA, Brennan PA, Najman J, Johnson KC, 2015. Social stress and the oxytocin receptor gene interact to predict antisocial behavior in an at-risk cohort. Dev. Psychopathol 27, 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AK, Kilaru V, Klengel T, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Conneely KN, Ressler KJ, Binder EB, 2015. DNA extracted from saliva for methylation studies of psychiatric traits: Evidence tissue specificity and relatedness to brain. Am. J. Med. Genet. B, Neuropsychiatr. Genet 168B, 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchiman HED, Slieker RC, Kremer D, Slagboom PE, Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, 2015. Design, measurement and processing of region-specific DNA methylation assays: The mass spectrometry-based method EpiTYPER. Front. Genet 6, 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, 1999. Identification and impact of risk and protective factors for drug use among urban African American adolescents. J. Clin. Child Psychol 28, 122– 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M,Bick J,2013DNA methylation: mechanism for embedding early life experiences in the genome. Child Dev 84, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tops M, Koole SL, H IJ, Buisman-Pijlman FT, 2014. Why social attachment and oxytocin protect against addiction and stress: Insights from the dynamics between ventral and dorsal corticostriatal systems. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 119, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Thomas PA, Liu H, Thomeer MB, 2014. Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. J. Health Soc. Behav 55, 20–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unternaehrer E, Luers P, Mill J, Dempster E, Meyer AH, Staehli S, Lieb R, Hellhammer DH, Meinlschmidt G, 2012. Dynamic changes in DNA methylation of stress-associated genes (OXTR, BDNF ) after acute psychosocial stress. Transl. Psychiatry 2, e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unternaehrer E, Meyer AH, Burkhardt SCA, Dempster E, Staehli S, Theill N, Lieb R, Meinlschmidt G, 2015. Childhood maternal care is associated with DNA methylation of the genes for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and oxytocin receptor (OXR) in peripheral blood cells in adult men and women. Stress 18, 451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaht M, Kurrikoff T, Laas K, Veidebaum T, Harro J, 2016. Oxytocin receptor gene variation rs53576 and alcohol abuse in a longitudinal population representative study. Psychoneuroendocrinol 74, 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt TT, 2008. The Race/Ethnic Age Crossover Effect in drug use and heavy drinking. J. Ethnicity Subst. Abuse 7, 93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, Smith GT, 2014. Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychol. Bull 140, 188–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]