Abstract

Background:

Treatment for epistaxis includes application of intranasal vasoconstrictors. These medications have a precaution against use in patients with hypertension. Given that many patients who present with epistaxis are hypertensive, these warnings are commonly overridden by clinical necessity.

Objectives:

To determine the effects of these medications on blood pressure.

Methods:

We conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial from November 2014 through July 2016. Adult patients being discharged from the emergency department (ED) at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) were recruited. Patients were ineligible if they had a contraindication to study medications, had a history of hypertension, were currently taking antihypertensive or antiarrhythmic medications, or had nasal abnormalities such as epistaxis. Subjects were randomized to 1 of 4 study arms (phenylephrine 0.25%; oxymetazoline 0.05%; lidocaine 1% with epinephrine 1:100,000; or bacteriostatic 0.9% sodium chloride [saline]). Blood pressure and heart rate were measured every 5 minutes for 30 minutes.

Results:

Sixty-eight patients were enrolled in the study; of these, 63 patients completed the study (oxymetazoline, n=15; phenylephrine, n=20; lidocaine with epinephrine, n=11; saline, n=17). We did not observe any significant differences in mean arterial pressure over time between phenylephrine and saline, oxymetazoline and saline, or lidocaine with epinephrine and saline. The mean greatest increases from baseline in mean arterial pressure, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate for each treatment group also were not significantly different from the saline group.

Conclusion:

Intranasal vasoconstrictors did not significantly increase blood pressure in patients without a history of hypertension. Our findings reinforce the practice of administering these medications to patients who present to the ED with epistaxis, regardless of high blood pressure.

Keywords: epinephrine, epistaxis, hemodynamics, oxymetazoline, phenylephrine

Introduction

Epistaxis is a common reason for presentation to the emergency department (ED), accounting for about 1 in 200 visits (1). Episodes appear to be more common in those younger than 10 years, older than 70, and those exposed to dry indoor heating in the winter months (2). Whether a relationship exists between systemic hypertension and epistaxis, and whether that relationship implies causation or correlates with increased severity of bleeding, remains controversial (3-6).

Initial management of epistaxis includes compression and application of topical intranasal vasoconstrictive medications by spray or by packing the nose with soaked pledgets (7-9). Application of these agents facilitates examination by reducing blood flow to the nasal mucosa, and in many cases, bleeding resolves with these conservative measures alone (10). Frequently recommended medications for this indication include cocaine, phenylephrine, oxymetazoline, and lidocaine with epinephrine (7-9, 11).

The administration of phenylephrine, oxymetazoline, and epinephrine for epistaxis is considered an off-label use, and all 3 agents have a precaution against use in patients with preexisting hypertension (12-14). However, strict avoidance of these agents in hypertensive patients with epistaxis would severely limit their applicability, given that patients often have elevated blood pressure during epistaxis and also may have comorbid hypertension. Thus, these warnings are commonly overridden by clinical necessity.

Studies regarding the hemodynamic effects, safety, and efficacy of intranasal vasoconstrictors have been conducted primarily in the operative setting, with the aim of facilitating either otolaryngologic procedures or nasal intubation (15-19). These studies have shown small changes in hemodynamics after administration, and these small effects on blood pressure have been similar when various agents were compared. Instrumentation of the nasal passages itself may limit our ability to apply the results of these studies to other clinical settings, given that such procedures have been independently reported to affect hemodynamics (20).

Therefore, we conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the hemodynamic effects of 3 commonly used medications for epistaxis treatment, lidocaine with epinephrine, phenylephrine, and oxymetazoline, in patients without a history of hypertension who presented to the ED. We hypothesized that these agents would not result in clinically significant increases in blood pressure when compared with a placebo.

Methods

Study Setting, Design, and Outcomes

A single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in the ED at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota), an academic, tertiary care hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT02285634). Study reporting adheres to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines for reporting parallel-group randomized trials (21).

The study statistician used a computerized random number generator to create a simple randomization schedule, which was then provided to the research pharmacy. Only the study statistician and the research pharmacy had access to the randomization schedule. After a patient was enrolled in the study, a custom order sheet with the patient’s study identification number was sent to the research pharmacy. The pharmacy then matched the patient with the randomization schedule, and the patient was allocated to 1 of 4 study arms: oxymetazoline 0.05%, phenylephrine 0.25%, lidocaine 1% with epinephrine 1:100,000, or bacteriostatic 0.9% sodium chloride (saline [placebo]). After study enrollment was complete, subject numbers were matched to the randomization schedule to complete the data set.

The primary outcome was the greatest increase from baseline in mean arterial pressure (MAP) after medication administration. Secondary outcomes were the greatest increase from baseline in systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR).

Selection of Participants

We aimed to enroll a convenience sample of patients discharged from the ED after they were evaluated for various conditions. Patients were excluded if they declined research consent, were younger than 18 years, were not fluent in English, or had known allergies to any of the study agents. We also excluded patients if they were currently receiving antihypertensive or antiarrhythmic agents, had clinically significant cardiopulmonary comorbidities (eg, a history of hypertension, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, heart failure), were known to be using a monoamine oxidase inhibitor agent, or had a history of angle closure glaucoma, benign prostatic hyperplasia, nasal surgery, or nasal abnormalities (including epistaxis).

Patient recruitment commenced on November 12, 2014, and was completed on July 29, 2016. Potentially eligible patients were identified by screening the ED census and by referral from ED staff members who were aware of the study and responsible for patient care. Recruitment was conducted by the investigators and by trained personnel. Patients were recruited from 6:00 AM through 4:00 PM, Monday through Friday, to match the working schedule of the research pharmacy. Written, informed consent was obtained by a member of the study team before study enrollment.

Study Protocol

Patients were placed in a supine posture on an ED gurney, with the head elevated by approximately 45°. Patients remained in this position for at least 5 minutes before measurement of baseline hemodynamic parameters. Standardized, appropriately sized blood pressure cuffs and continuous pulse-oximetry finger probes were applied to the patient for monitoring.

Study drugs were dispensed in 5-mL quantities in unlabeled syringes. All 4 medications were colorless and visually indistinguishable. After measurement of baseline vital signs, half of a standard cotton ball was soaked in the study drug and placed in an anterior naris (the patient could indicate a preference for which side; otherwise, study personnel selected the side). A standard plastic nose clip, typically used for patients with epistaxis, was placed over the cartilaginous part of the nose.

Hemodynamic measurements were taken 5 minutes after application of the study drug and then in 5-minute intervals thereafter for a half hour. After the third measurement at 15 minutes, the nasal clip and cotton ball were removed, mimicking standard practice in our department for patients with epistaxis; 3 additional measurements were obtained without the medication in place (total of 6 measurements, not including the baseline measure). The total observation time of 30 minutes was selected to include the expected time to peak effect for all 3 active agents. After completion of the study protocol, any adverse effects were recorded. Subjects were compensated for their participation by a mailed check, per institutional policy.

Data Collection and Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic (22). REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources. Baseline information included age, sex, chief complaint for the corresponding ED visit, medical history, and allergies. Hemodynamic measurements included SBP, DBP, MAP, and HR, and oxygen saturation.

Continuous measurements were summarized with means and standard deviations. Categorical data were summarized with frequency counts and percentages. Differences in baseline features and the primary outcome (greatest increase in MAP from baseline) were evaluated with Fisher exact tests and analysis of variance by comparing each treatment arm with the control group (saline). Additionally, for each treatment arm, changes in hemodynamic measures over time were compared with the control (saline) with repeated-measures analysis of variance. Statistical analyses were performed by using the SAS software package (v. 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) and Stata statistical software (StataCorp). All tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Study Power

Based on previously reported population data, we anticipated a mean (SD) MAP of 80 (10) mm Hg in our study sample (23). A difference of 8 mm Hg was believed to be clinically significant. With these specifications, we estimated that 25 participants per treatment arm would have 80% power to detect a difference of 8 mm Hg among the 4 groups by 1-way analysis of variance, with an α of 0.05.

Results

From November 2014 through July 2016, 68 patients were enrolled and randomized to a study arm. The trial was discontinued prematurely because of recruitment failure in the anticipated time frame. Five subjects withdrew from the study after randomization and drug allocation (lidocaine with epinephrine, n=4; saline, n=1) but before baseline measurements were obtained; subjects withdrew because of time constraints or unwillingness to wait. In total, data from 63 patients were analyzed; 15 patients were randomized to the oxymetazoline group, 20 to the phenylephrine group, 11 to the lidocaine with epinephrine group, and 17 to the saline group. No patients withdrew after baseline measurements were obtained. Subject allocation is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Subject Recruitment, Allocation, and Completion. ED indicates emergency department.

Median participant age was 33.5 years (interquartile range [IQR], 23.5-44.5 years), with the phenylephrine group having the highest median age (40 years; IQR, 23-51 years) and the saline group having the lowest median age (31.5 years; IQR, 23-40 years). The youngest participant was 18 years old and the oldest was 74. Twenty-nine women (46%) and 34 men (54%) were included in the analysis. Major comorbidities were rare, and chief complaints for the index ED visit were diverse. These features are summarized by treatment group in Table 1. Baseline hemodynamic measures did not vary significantly among treatment groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Features, Adverse Effects, and Primary Outcome (N=63)

| Treatment |

P Value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Lidocaine With Epinephrine (n=11) |

Oxymetazoline (n=15) |

Phenylephrine (n=20) |

Saline (n=17) |

Lidocaine With Epinephrine vs Saline |

Oxymetazoline vs Saline |

Phenylephrine vs Saline |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 2 (18) | 11 (73) | 8 (40) | 8 (47) | .23 | .13 | .67 |

| Chief complaint | .32 | .98 | .91 | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 0 (0) | 3 (20) | 4 (20) | 3 (18) | |||

| Chest pain | 2 (18) | 3 (20) | 7 (35) | 3 (18) | |||

| Dental | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (6) | |||

| Dizziness | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |||

| Dyspnea | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 1 (6) | |||

| Headache | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |||

| Infectious | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |||

| Musculoskeletal | 3 (27) | 5 (33) | 1 (5) | 3 (18) | |||

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (6) | |||

| Skin | 5 (45) | 2 (13) | 1 (5) | 1 (6) | |||

| Syncope | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |||

| Urology | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (5) | 1 (6) | |||

| Weakness | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |||

| Adverse effecta | 0 (0) | 4 (27) | 3 (15) | 2 (12) | .51 | .38 | >.99 |

| Dizziness | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | NC | NC | NC |

| Nasal pain or burning | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | NC | NC | NC |

| Other adverse effect | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 1 (5) | 2 (12) | .51 | >.99 | .58 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 38.6 (15.7) | 34.5 (15.0) | 40.0 (16.8) | 31.2 (10.1) | .20 | .53 | .08 |

| Baseline hemodynamics, mean (SD) | |||||||

| MAP, mm Hg | 86.3 (15.9) | 81.2 (11.2) | 80.6 (11.6) | 79.8 (8.9) | .16 | .74 | .85 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 123.2 (14.3) | 121.3 (13.7) | 115.7 (16.6) | 113.3 (11.4) | .08 | .12 | .61 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg |

73.7 (15.6) | 68.9 (11.3) | 68.8 (12.3) | 67.8 (8.6) | .20 | .80 | .81 |

| Heart rate, beats/minuteb | 71.5 (14.1) | 77.0 (11.5) | 67.6 (12.7) | 75.9 (15.9) | .40 | .82 | .07 |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 97.2 (1.8) | 97.1 (2.5) | 97.6 (2.1) | 97.9 (1.7) | .37 | .30 | .67 |

| Highest MAP, mm Hg | 90.8 (11.1) | 86.3 (12.4) | 86.9 (11.0) | 86.4 (8.8) | .29 | .98 | .88 |

| Change in MAP, mm Hgc | 4.6 (8.0) | 5.1 (6.8) | 6.4 (5.8) | 6.5 (5.5) | .42 | .52 | .93 |

Abbreviations: MAP, mean arterial pressure; NC, not calculated (complication occurred in <5 patients).

No subjects reported chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, headache, blurry vision, or flushing.

One patient in the saline group had a heart rate that exceeded 120 beats/minute throughout the monitoring period. The mean (SD) heart rate at baseline after excluding this subject was 72.6 (8.4) beats/minute.P values for the comparisons of lidocaine with epinephrine vs saline, oxymetazoline vs saline, and phenylephrine vs saline after excluding this subject were .81, .30, and .21, respectively.

Calculated as the highest MAP observed minus the baseline MAP.

MAP did not significantly increase for any treatment group compared with saline. Mean (SD; 95% CI) increase in MAP from baseline after drug administration was: 4.6 (8.0; −0.8 to 9.9) mm Hg for lidocaine with epinephrine, 5.1 (6.8; 1.3 to 8.8) mm Hg for oxymetazoline, 6.4 (5.8; 3.7 to 9.1) mm Hg for phenylephrine, and 6.5 (5.5; 3.7 to 9.3) mm Hg for saline. We observed no clinically or statistically significant differences in the mean increase in SBP, DBP, or HR from baseline across groups. These data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Greatest Increase in Hemodynamic Measurements After Administration of Vasoconstrictor Medicationsa

| Treatment |

P Value Difference Between Means (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Phenylephrine (n=20) |

Oxy- metazoline (n=15) |

Lidocaine With Epinephrine (n=11) |

Saline (n=17) | Lidocaine With Epinephrine vs Saline |

Oxymetazoline vs Saline |

Phenylephrine vs Saline |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD; 95% CI), mm Hg | 8.2 (7.2; 4.8 to 11.6) | 7.5 (9.8; 2.1 to 13.0) | 3.5 (6.5;−0.9 to 7.8) | 8.9 (5.4; 6.1 to 11.7) | .06 −5.4 (−12.3 to 1.5) |

.61 −1.4 (−7.7 to 5.0) |

.78 −0.7 (−6.6 to 5.2) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD; 95% CI), mm Hg | 7.9 (6.8; 4.7 to 11.1) | 5.7 (7.7; 1.5 to 10.0) | 6.2 (8.3; 0.6 to 11.8) | 9.3 (6.6; 5.9 to 12.7) | .27 −3.1 (−9.9 to 3.7) |

.17 −3.6 (−9.8 to 2.7) |

.56 −1.4 (−7.2 to 4.4) |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean (SD; 95% CI), mm Hg | 6.4 (5.8; 3.7 to 9.1) | 5.1 (6.8; 1.3 to 8.8) | 4.6 (8.0; −0.8 to 9.9) | 6.5 (5.5; 3.7 to 9.3) | .42 −2.0 (−8.0 to 4.0) |

.52 −1.5 (−6.9 to 4.0) |

.93 −0.2 (−5.3 to 4.9) |

| Heart rate, mean (SD; 95% CI), beats/minb | 5.2 (6.6; 2.1 to 8.3) | 2.8 (5.2; −0.1 to 5.7) | 7.5 (9.7; 1.0 to 14.1) | 6.8 (5.6; 4.0 to 9.7) | .78 0.7 (−5.6 to 7.0) |

.10 −4.0 (−9.8 to 1.7) |

.47 −1.6 (−7.0 to 3.7) |

Calculated as the highest increase from baseline.

One patient in the saline group had a heart rate that exceeded 120 beats/minute throughout the monitoring period. The mean greatest increase in heart rate when excluding this subject’s data was 6.5 (SD, 5.5; 95% CI, 3.7-9.3) beats/minute. P values for the comparisons of lidocaine with epinephrine vs saline, oxymetazoline vs saline, and phenylephrine vs saline after excluding this subject were .80, .10, and .46, respectively.

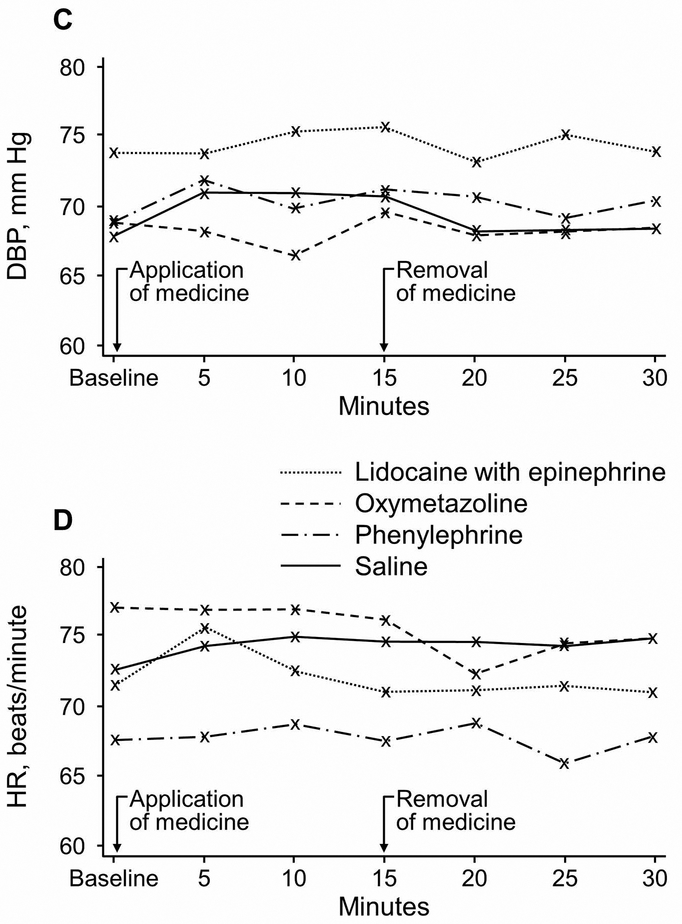

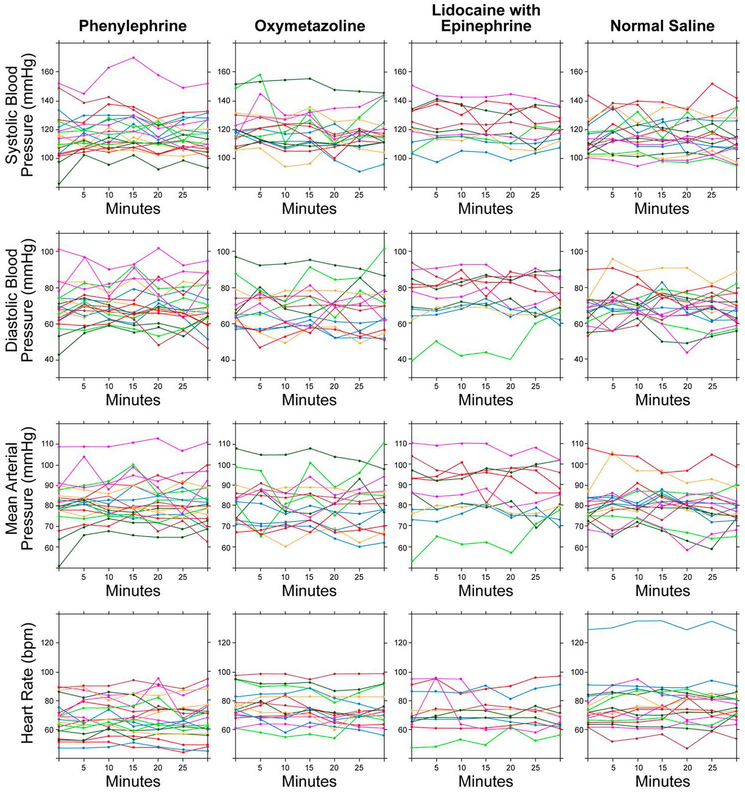

Hemodynamic measurements throughout the study protocol are summarized in Figure 2. One subject randomized to the saline group had HR measurements that consistently exceeded 120 beats/minute; HR data were analyzed with and without this subject’s data and results were similar. Plots of all hemodynamic measurements for each study participant are provided in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Hemodynamic Measures After Administration of Topical Intranasal Vasoconstrictors. A, Systolic blood pressure (SBP). B, Mean arterial pressure (MAP). C, Diastolic blood pressure (DBP). D, Heart rate (HR).

Figure 3.

Individual Participants’ Hemodynamic Measurements After Administration of Topical Intranasal Vasoconstrictors. bpm indicates beats per minute.

Adverse effects were reported by 9 patients (14.3%). In the oxymetazoline group, patients reported nasal pain (n=2) and eye watering (n=1). Both patients who reported nasal pain were unsure whether it was caused by the clip or by the medication. In the phenylephrine group, patients reported nasal pain (n=2) and dizziness (n=1). Four patients reported an unpleasant aftertaste (oxymetazoline, n=1; phenylephrine, n=1; saline, n=2).

Discussion

We conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial that examined the hemodynamic effects of intranasal vasoconstrictors commonly used to treat epistaxis. We observed no significant change in MAP, SBP, DBP, or HR. Although failure to achieve our target enrollment may have resulted in insufficient power to detect statistically significant differences, we did not observe any patterns of increasing blood pressure after administering intranasal vasoconstrictors. In fact, the highest mean increase in blood pressure was observed in the placebo group.

Intranasal epinephrine, oxymetazoline, and phenylephrine have each been associated with hypertensive crises, with some case reports describing severe consequences such as pulmonary edema, cardiovascular collapse, and even death (24-31). These events have been primarily reported in the operative setting and often involve children undergoing otolaryngologic procedures. Reports have further noted an association between β-blocker administration and intranasal vasoconstrictor—induced hypertension (24, 32, 33).

Beyond these case reports, few recent studies have specifically addressed hemodynamic changes associated with intranasal vasoconstrictor medication application. Past studies typically were performed in periprocedural settings, lacked a placebo group, and compared patient hemodynamics before and after administration as a secondary objective (15, 16, 18, 19, 34, 35). These study designs may be confounded by concurrent medications and procedures, particularly in the case of nasal intubation, which independently can produce hypertension (16, 20). However, even considering these confounders, prior studies have not identified a clinically significant pressor response to intranasal vasoconstrictor medication. In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment, phenylephrine or saline was administered intranasally to 12 patients without hypertension and 14 patients with hypertension and long-term metoprolol treatment (36). No statistically or clinically significant increases in blood pressure were identified, despite doses that were 3 to 40 times higher than the manufacturer’s recommended dose. Thus, our findings are consistent with those of previous studies, which have shown that these agents do not increase blood pressure when administered intranasally.

Most published studies indicate that patients who present with epistaxis have higher blood pressure than controls without epistaxis (37), but it is unclear whether this difference represents actual underlying hypertension (38). Patients with higher blood pressure may also have more severe episodes and require more invasive interventions (39). Although the question of causality remains unresolved, many or most patients who present with epistaxis clearly are hypertensive. Topical vasoconstrictors are simultaneously the first-line treatment for epistaxis and contraindicated in patients with hypertension, even though this contraindication is frequently bypassed in standard practice. Our study suggests that the standard practice is reasonable. Although these agents may rarely precipitate a hypertensive crisis, they do not appear to result in increased blood pressure during routine use. However, further study in patients with chronic hypertension, as well as those with epistaxis, is warranted.

Strengths of our study include the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled design, as well as the standardized method of administration that mimics the typical clinical approach to epistaxis control, ie, cotton pledgets soaked in medication and then applied in conjunction with a nasal clip. Pledget application has been posited to increase systemic absorption, which therefore makes this method of drug administration an important consideration (24).

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size that did not meet our target enrollment goal of 100 patients, based on the power calculation. Enrollment was markedly more difficult than we had anticipated. We aimed to increase study generalizability to the clinical scenario of the acute treatment of epistaxis by conducting the study in the ED and by enrolling patients being discharged from the ED, but this strategy proved difficult because patients were anxious to leave the department immediately after discharge. In addition, the research pharmacy hours coincided with low-volume periods of ED visits. Enrollment was further limited by the exclusion of patients with hypertension, which is estimated to affect about 30% of the general US population and undoubtedly was even more common among patients being seen in the ED.

Additionally, although we did not observe any trends of increasing blood pressure in our study, it is possible or perhaps probable that individual patients can have abnormal responses to these agents, with deleterious effects. However, these adverse events may have no relationship to preexisting hypertension, particularly given that they are most commonly reported in children (24, 26, 33). Importantly, the study excluded children and adults with hypertension, the 2 groups most in need of further study. Children were excluded because of concerns about obtaining consent, tolerance to completing the protocol while obtaining measurements that are sensitive to activity, and ethical concerns about potential harm in this population. Furthermore, dosing would be more variable relative to the size of the naris and body mass. Patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of hypertension were excluded because of ethical concerns about potential harm. Our study strengthens the argument that a study including these 2 groups would be ethically permissible. We also did not study patients who had epistaxis. Damage to the nasal mucosa might lead to increased systemic absorption and therefore increased hemodynamic effects. However, it might be difficult to justify use of placebo in these cases, given the efficacy of vasoconstrictors in stopping bleeding. One possible option would be to use a purely hemostatic agent, as opposed to a vasoconstrictor, in 1 comparison group.

Conclusions

Intranasal oxymetazoline, phenylephrine, and lidocaine with epinephrine do not appear to increase systemic blood pressure in adults without a history of hypertension who are being discharged from the ED. Further study is indicated in patients with a history of hypertension and antihypertensive medication use and in patients presenting with epistaxis. Our findings reinforce the current common practice of using these medications in patients who present to the ED with epistaxis, regardless of blood pressure, because these medications do not appear to affect systemic hemodynamics.

Article Summary

1). Why is this topic important?

Topical vasoconstrictors such as phenylephrine, oxymetazoline, and epinephrine are first-line treatments for epistaxis, but all 3 agents have a precaution against use in hypertensive patients. Strict avoidance of these agents in hypertensive patients with epistaxis would severely limit their applicability, given that patients presenting with epistaxis often have elevated blood pressure or preexisting hypertension.

2). What does this study attempt to show?

We aimed to determine whether intranasal application of any of these 3 medications resulted in an increase in systemic blood pressure.

3). What are the key findings?

We observed no significant change in mean arterial, systolic, or diastolic pressure or heart rate after application of topical vasoconstrictors.

4). How is patient care impacted?

These findings reinforce the common practice of using these medications in patients who present to the emergency department with epistaxis, regardless of blood pressure. These medications do not appear to affect systemic hemodynamics.

Acknowledgment

This publication was supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr Bellew receives support from the Office of Academic Affiliation (OAA), Department of Veterans Affairs, VA National Quality Scholars Program, and use of the facilities of VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, Tennessee.

The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- ED

emergency department

- HR

heart rate

- IQR

interquartile range

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Footnotes

Trial Registration: This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT02285634).

Portions of this manuscript were previously published in an abstract in: Bellew SD, Johnson KL, Kummer T. 320 Do Intranasal Vasoconstrictors Increase Blood Pressure? A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70(4): S126.

Conflict of interest: None.

Contributor Information

Dr Shawna D. Bellew, Department of Emergency Medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, and VA National Quality Scholars Program, VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville.

Dr Katie L. Johnson, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota..

Mr Micah D. Nichols, Bethel University, St Paul, Minnesota..

Dr Tobias Kummer, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota..

References

- [1].Pallin DJ, Chng YM, McKay MP, Emond JA, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA Jr. Epidemiology of epistaxis in US emergency departments, 1992 to 2001. Ann Emerg Med 2005;46:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chaaban MR, Zhang D, Resto V, Goodwin JS. Demographic, Seasonal, and Geographic Differences in Emergency Department Visits for Epistaxis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;156:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petruson B, Rudin R, Svardsudd K. Is high blood pressure an aetiological factor in epistaxis? ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1977;39:155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ibrashi F, Sabri N, Eldawi M, Belal A. Effect of atherosclerosis and hypertension on arterial epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 1978;92:877–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lubianca Neto JF, Fuchs FD, Facco SR, et al. Is epistaxis evidence of end-organ damage in patients with hypertension? Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Herkner H, Havel C, Mullner M, et al. Active epistaxis at ED presentation is associated with arterial hypertension. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:92–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. Emergency Medicine : Concepts and Clinical Practice. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. Tintinalli’s emergency medicine a comprehensive study guide. Eighth edition ed. New York Chicago San Francisco: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW, Hedges JR. Roberts and Hedges’ clinical procedures in emergency medicine. Sixth edition ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Traboulsi H, Alam E, Hadi U. Changing Trends in the Management of Epistaxis. Int J Otolaryngol 2015;2015:263987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alter H Approach to the adult with epistaxis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-adult-with-epistaxis. Last accessed November 28/.

- [12].Truven Health Analytics. Phenylephrine Hydrochloride (electronic version). http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/.

- [13].Truven Health Analytics. Epinephrine (electronic version). http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/. Last accessed Nov 28, 2017/.

- [14].Truven Health Analytics. Oxymetazoline Hydrochloride (electronic version). http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/.

- [15].Kameyama K, Watanabe S, Kano T, Kusukawa J. Effects of nasal application of an epinephrine and lidocaine mixture on the hemodynamics and nasal mucosa in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66:2226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Katz RI, Hovagim AR, Finkelstein HS, Grinberg Y, Boccio RV, Poppers PJ. A comparison of cocaine, lidocaine with epinephrine, and oxymetazoline for prevention of epistaxis on nasotracheal intubation. J Clin Anesth 1990;2:16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Saif AM, Farboud A, Delfosse E, Pope L, Adke M. Assessing the safety and efficacy of drugs used in preparing the nose for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: a systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol 2016;41:546–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Latorre F, Otter W, Kleemann PP, Dick W, Jage J. Cocaine or phenylephrine/lignocaine for nasal fibreoptic intubation? Eur J Anaesthesiol 1996;13:577–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gross JB, Hartigan ML, Schaffer DW. A suitable substitute for 4% cocaine before blind nasotracheal intubation: 3% lidocaine-0.25% phenylephrine nasal spray. Anesth Analg. 1984;63:915–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Singh S, Smith JE. Cardiovascular changes after the three stages of nasotracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 2003;91:667–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2010;1:100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].O’Brien E, Atkins N, O’Malley K. Defining normal ambulatory blood pressure. Am J Hypertens 1993;6:201S–6S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tobias JD, Cartabuke R, Taghon T. Oxymetazoline (Afrin(R)): maybe there is more that we need to know. Paediatr Anaesth 2014;24:795–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rajpal S, Morris LA, Akkus NI. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction with the use of oxymetazoline nasal spray. Rev Port Cardiol 2014;33:51 e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Latham GJ, Jardine DS. Oxymetazoline and hypertensive crisis in a child: can we prevent it? Paediatr Anaesth 2013;23:952–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schwalm JD, Hamstra J, Mulji A, Velianou JL. Cardiogenic shock following nasal septoplasty: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Anaesth 2008;55:376–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Son JS, Lee SK. Pulmonary edema following phenylephrine intranasal spray administration during the induction of general anesthesia in a child. Yonsei Med J 2005;46:305–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Montastruc F, Montastruc G, Taudou MJ, Olivier-Abbal P, Montastruc JL, Bondon-Guitton E. Acute coronary syndrome after nasal spray of oxymetazoline. Chest. 2014;146:e214–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hecker RB, Hays JV, Champ JD, Rubal BJ. Myocardial ischemia and stunning induced by topical intranasal phenylephrine pledgets. Mil Med 1997;162:832–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Thrush DN. Cardiac arrest after oxymetazoline nasal spray. J Clin Anesth 1995;7:512–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kalyanaraman M, Carpenter RL, McGlew MJ, Guertin SR. Cardiopulmonary compromise after use of topical and submucosal alpha-agonists: possible added complication by the use of beta-blocker therapy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;117:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Groudine SB, Hollinger I, Jones J, DeBouno BA. New York State guidelines on the topical use of phenylephrine in the operating room. The Phenylephrine Advisory Committee. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:859–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Alhaddad ST, Khanna AK, Mascha EJ, Abdelmalak BB. Phenylephrine as an alternative to cocaine for nasal vasoconstriction before nasal surgery: A randomised trial. Indian J Anaesth 2013;57:163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Giannakopoulos H, Levin LM, Chou JC, et al. The cardiovascular effects and pharmacokinetics of intranasal tetracaine plus oxymetazoline: preliminary findings. J Am Dent Assoc 2012;143:872–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Myers MG, Iazzetta JJ. Intranasally administered phenylephrine and blood pressure. Can Med Assoc J 1982;127:365–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kikidis D, Tsioufis K, Papanikolaou V, Zerva K, Hantzakos A. Is epistaxis associated with arterial hypertension? A systematic review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2014;271:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Theodosis P, Mouktaroudi M, Papadogiannis D, Ladas S, Papaspyrou S. Epistaxis of patients admitted in the emergency department is not indicative of underlying arterial hypertension. Rhinology. 2009;47:260–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sarhan NA, Algamal AM. Relationship between epistaxis and hypertension: A cause and effect or coincidence? J Saudi Heart Assoc 2015;27:79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]