Abstract

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) is a life-threatening malignancy. The level of the cell growth regulator mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3 (MAP4K3) has been shown to be correlated with a high risk of NSCLC recurrence and poor recurrence-free survival rate. The present study examined the effects of Astragalus polysaccharide (APS) and 10-hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT), which are associated with marked suppression and dephosphorylation of the MAP4K3/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, in the H1299 NSCLC cell line. APS and HCPT decreased H1299 cell viability, induced apoptosis and altered the cell cycle stages, as evaluated using an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay and flow cytometric analysis. Furthermore, APS increased the expression of apoptosis-associated genes B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX), of proteases cysteine-aspartic acid protease (caspase)-3 and -9, and of cytochrome c. HCPT promoted autophagy in H1299 cells, with concomitant suppression of the expression of MAP4K3 and downregulation of mTOR signaling. Notably, combination treatment with the two agents reduced the migration and invasion of H1299 cells compared with the single treatments. It was also demonstrated that the overexpression of MAP4K3 promoted the migration and invasion of H1299 cells, and that the kinase activity was essential to this. These findings suggested that MAP4K3 may be an attractive target for the treatment of NSCLC

Keywords: Astragalus polysaccharide, 10-hydroxycamptothecin, antimetastatic, non-small cell lung carcinoma, H1299, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3/mammalian target of rapamycin

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common aggressive malignancies and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for ~85% of lung cancer-associated mortalities (1). Metastasis is common in patients with NSCLC and early metastasis is responsible for a majority that succumb to the disease (2,3). Random genetic and epigenetic mutations in cancer cells, combined with a plastic and responsive microenvironment, support the metastatic evolution of tumors. Metastasis comprises a series of complex processes requiring the interaction of different signaling pathways; it involves the detachment of tumor cells, the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM), the invasion, migration and adhesion of endothelial cells, and the re-establishment of growth at distant sites (4,5). Genes associated with the initiation of metastasis and virulence operate in the early and late stages of invasion and growth, when located within the primary tumor and in various metastatic environments, respectively (6). A previous study suggested that the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway was involved in the transformation and neoplastic proliferation of human NSCLC malignancies. Constitutive activation of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mTOR signaling pathway occurs in 90% of NSCLC cell lines (7). The mTOR signaling pathway primarily regulates growth by affecting ribosome biogenesis, protein translation and autophagy, and has emerged as a promising target for therapies against diseases, including cancer and diabetes (8). It appears to be a prime strategic target for inhibiting the proliferation, invasion and migration of thyroid cancer, breast cancer, glioblastoma and gastric adenocarcinoma (9-12).

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3 (MAP4K3), also termed germinal center-like kinase, is a regulator of cell growth that is required for maximal mTORC1-dependent S6K/4E-BP1 phosphorylation in cell cultures (13,14). In addition to promoting the activation of mTORC1, there is evidence that MAP4K3 is involved in tumor metastasis, viability and apoptosis. MicroRNA let-7c has been reported to inhibit the migration and invasion of SKEMS-1 cells by targeting MAP4K3 (15) and MAP4K3 knockdown almost eradicated breast cancer cell migration (16). MAP4K3 is overexpressed in pulmonary tissues of patients with NSCLC and its overexpression is correlated with high recurrence risk and poor recurrence-free survival rates (17). Therefore, MAP4K3 may be a prognostic biomarker for NSCLC recurrence and a promising antimetastatic and antitumor target.

To assist in developing superior anti-NSCLC treatments, the present study examined a panel of compounds with anti-MAP4K3 activity and identified two targets, Astragalus polysaccharide (APS) and 10-hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT). APS is an active ingredient found in the dried roots of Astragalus membranaceus, a herb used in numerous traditional Chinese medicines (18,19), and HCPT, a natural camptothecin (CPT) derivative, has increased antitumor activity and decreased toxicity compared with CPT (20). In the present study, the anti-NSCLC effects of APS and HCPT on H1299 cells were investigated following single and combination treatments.

Materials and methods

Reagents, antibodies and plasmid constructs

pRK5myc-MAP4K3 (M4K3) and AFG kinase-dead (KD) MAP4K3 were prepared as described previously (13). APS [2-(chlorom ethyl)-4-(4-nitrophenyl)-1,3-thiazole; ≥98%] was purchased from ShangHai YuanYe Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China; CAS no. 89250-26-0; cat. no. C18M6Y1). HCPT (98%) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China; CAS no. 19685-09-7; cat. no. H1524105). 3-methyladenine (3-MA) and chloroquine (CQ) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from HyClone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Logan, UT, USA) and penicillin G, streptomycin and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) were from Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). p-nitrobenzyl mesylate (PNBM) was from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA, USA). Myelin basic protein (MBP), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and isopropyl alcohol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, EMD Millipore. β-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb; cat. no. ab8226), Bax rabbit antibody (Ab; cat. no. 2772), Bcl-2 rabbit mAb (cat. no. 3498), caspase-3 rabbit Ab (cat. no. 9662), caspase-9 rabbit Ab (cat. no. 9502S), cytochrome c (D18C7) rabbit mAb (cat. no. 11940S), p70S6K mouse mAb (cat. no. 611261), phospho-p70 S6K (Thr389) rabbit Ab (cat. no. 9205), MAP4K3 rabbit Ab (cat. no. PAB3189), anti-myc 9E10 mouse mAb (cat. no. 05-419), thiophosphate ester rabbit mAb (cat. no. ab92570), microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) rabbit Ab (cat. no. 8025) and P62 rabbit mAb (cat. no. 11940) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA), Abcam (Cambridge, UK) or BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; cat. no. 31460) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. 31430) antibodies were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Cell culture and transfection

Human H1299 NSCLC cells (H1299), NCI H460 (H460) cells and 293T cells were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology and Biochemistry, and the Chinese Type Culture Collection, Shanghai, China). The cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

For transfection, the cell lines were plated at 5 ×105 cells/well in 6-well plates and incubated overnight prior to transfection with Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Unless otherwise specified, H1299 cells or H460 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg pRK5myc Vec, 0.5 µg AFG MAP4K3-KD or 0.5 µg pRK5myc M4K3 and cultured for 24 h, after which, they were used in subsequent experiments.

MAP4K3 in vitro kinase activity assay

Immunoprecipitated myc-tagged MAP4K3 from 293T cells, produced as previously described (13), were incubated with MBP as a substrate and the indicated agents. To screen for inhibitors of MAP4K3 by western blot analysis, ATPγS was used at a concentration of 1 mM in appropriate kinase buffers (21). The proteins were alkylated with 2.5 mM PNBM for 2 h at room temperature (18-22°C) and the products were analyzed by western blot analysis.

Cell viability

The H1299 cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and incubated for 24 h. Following treatment with the agents at the indicated concentrations and times, cell viability was evaluated using an MTT assay, which is based on the reduction of a tetrazolium salt by mitochondrial dehydrogenase by viable cells. Following treatment, MTT solution (final concentration, 500 µg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The formed formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

Cell cycles were analyzed using a propidium iodide (PI) cell cycle detection kit (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, centrifuged at 190 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and the concentration was adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml. The cells were resuspended in solution A at room temperature for 10 min. Solution B was added for 10 min and the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled PI at room temperature for 15 min under light-protected conditions.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a BD FACSAria II Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences). The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated using BD FACSDiva Software v7.0 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The apoptotic indices were determined using a FITC-labeled Annexin V/PI apoptosis detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich, EMD Millipore). Briefly, the cells were harvested, washed with PBS and centrifuged at 190 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml, resuspended in binding buffer and stained with FITC-labeled Annexin V/PI at room temperature for 15 min under light-protected conditions. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Wound-healing assay

Wound healing was assayed as previously described with modifications (22). Briefly, the H1299 cells and H460 cells were cultured to confluence in 6-well cell culture plates for 24 h in serum-free medium, respectively. The medium was replaced with serum-containing medium followed by the addition of APS or/and HCPT, and cell monolayers were disrupted by scraping with a 100-µl micropipette tip. At the indicated times (0 and 24 h without transfection; 0,19 and 60 h with transfection) following scraping, the cells were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.4) and images were captured using an optical microscope at ×40 magnification.

In vitro migration and invasion assay

The chemotactic directional migration of H1299 cells was measured using 24-well Transwell inserts. Pore filters (8-µm; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) were coated with gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, EMD Millipore). Following culture for 24 h in serum-free DMEM, the cells were resuspended in serum-free medium, seeded in the upper chambers of the Transwell inserts (1×105 cells/ml) and incubated with APS and/or HCPT. DMEM containing 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber. The cells in each treatment group were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 95% air and 5% CO2. The filters were stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Cells that had migrated and adhered to the underside of the filters were counted and images were captured using an optical microscope at × 40 magnification. The invasiveness of the H1299 cells was measured using Matrigel-coated Transwell cell culture chambers (8-µm pore size) as previously described. The method was the same as for migration analysis. Cells that had penetrated through the Matrigel coating and adhered to the lower surface of the filters were counted and images were captured using an optical microscope at ×40 magnification.

Western blot analysis

The cells were washed in 1X PBS and lysed in lysis buffer as described (13). The total protein concentrations was determined using the Bradford method. The total protein or protein fractions (50 µg/lane) were loaded and separated by 10 or 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder for 45 min at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies directed against β-actin (dilution 1:2,000), Bax (dilution 1:1,000), Bcl-2 (dilution 1:1,000), caspase-3 (dilution 1:1,000), caspase-9 (dilution 1:1,000), cytochrome c dilution 1:1,000), p70S6K (dilution 1:500), phospho-p70 S6K (Thr389) (dilution 1:1,000), MAP4K3 rabbit Ab (dilution 1:500), myc (dilution 1:2,000), thiophosphate ester (dilution 1:5,000), LC3 (dilution 1:1,000) and P62 (dilution 1:1,000) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were subsequently washed three times with PBS-0.1% Tween-20 for 10 min and were then incubated with goat anti-mouse (dilution 1:10,000) or goat anti-rabbit (dilution 1:5,000) secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The expression of individual proteins was detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Applygen Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China). The densitometric values of the bands were measured using ImageQuant TL software (version 8.1; GE Life Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences between groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test with SPSS 14.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

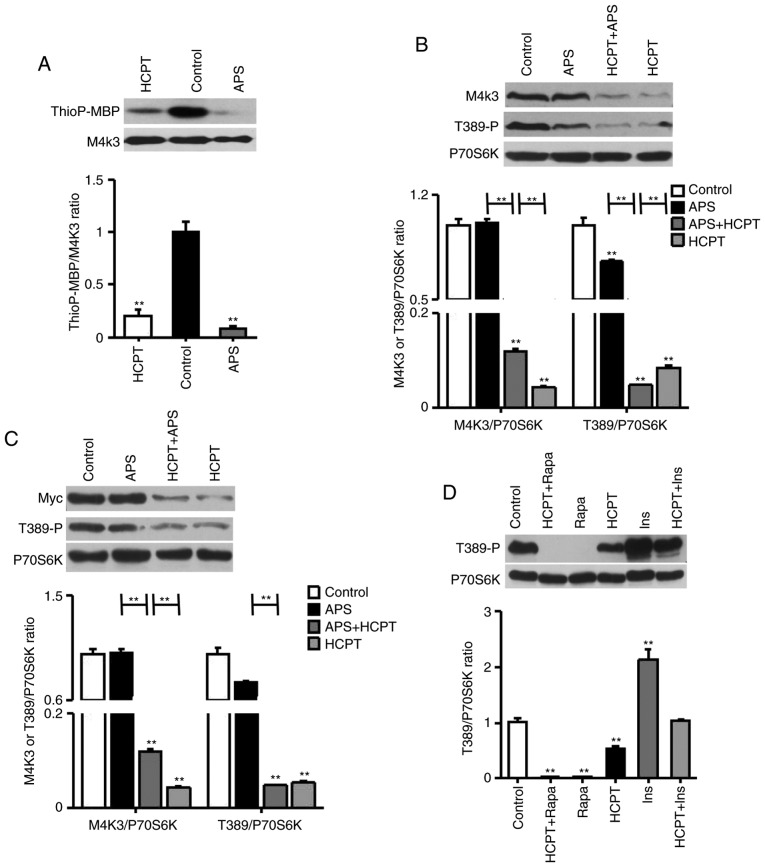

Effects of APS, HCPT and their combination on MAP4K3 and mTOR signaling in H1299 cells

To identify an inhibitor specific for MAP4K3, the in vitro activity of MAP4K3 was measured by incubating the kinase with the generic substrate MBP. In the presence of ATPγS, MAP4K3 kinase activity was markedly inhibited by APS and HCPT (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

APS, HCPT and the combination of APS and HCPT inhibit the MAP4K3/mTOR signaling pathway in H1299 cells. (A) In vitro kinase assays using WT-MAP4K3 immunoprecipitated from 293T cells with myelin basic protein as a substrate, ATPγS as a phospho-donor and 1 mg/ml APS or 1 µM HCPT incubated at 30°C for 30 min. (B) Endogenous expression of MAP4K3 and Thr389-phosphorylation of S6K in H1299 cells, detected by western blot analysis following incubation with 1 mg/ml APS or 1 µM HCPT, or the combined agents, for 24 h. (C) H1299 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg pRK5mycMAP4K3, serum-starved for 16 h and treated for 24 h with 1 mg/ml APS or 1 µM HCPT, or the combined agents. (D) Thr389-phosphorylation of S6K in H1299 cells was assessed via western blot analysis. Serum-starved cells were incubated with 1 µM Ins for 30 min or 1 µM HCPT for 24 h, or Ins followed by HCPT; or, cells were treated with 50 nM Rapa for 1 h or 1 µM HCPT for 24 h, or with Rapa followed by HCPT. Western blot results are representative of three independent experiments. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin; M4K3, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; WT, wild-type; Rapa, rapamycin; Ins, insulin. **P<0.01, vs. untreated control.

Subsequently, it was demonstrated that APS and HCPT inhibited the phosphorylation of S6K. The endogenous expression of MAP4K3 in H1299 cells was markedly reduced by HCPT, although not by APS (Fig. 1B). HCPT and the combined agents inhibited S6K phosphorylation at Thr389 by 10.02±0.01 and 20.89±0.01-fold, respectively, which was increased compared with APS (1.33±0.02-fold). In addition, the overexpression of MAP4K3 reduced the inhibition of mTOR signaling in the presence of APS, although not when treated with HCPT or the combined agents (Fig. 1C). Unlike rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTOR, HCPT was observed to partially inhibit insulin-responsive mTOR activation (Fig. 1D). These results suggested that the two agents impaired the activation of MAP4K3 and act on the mTOR signaling pathway in a similar manner.

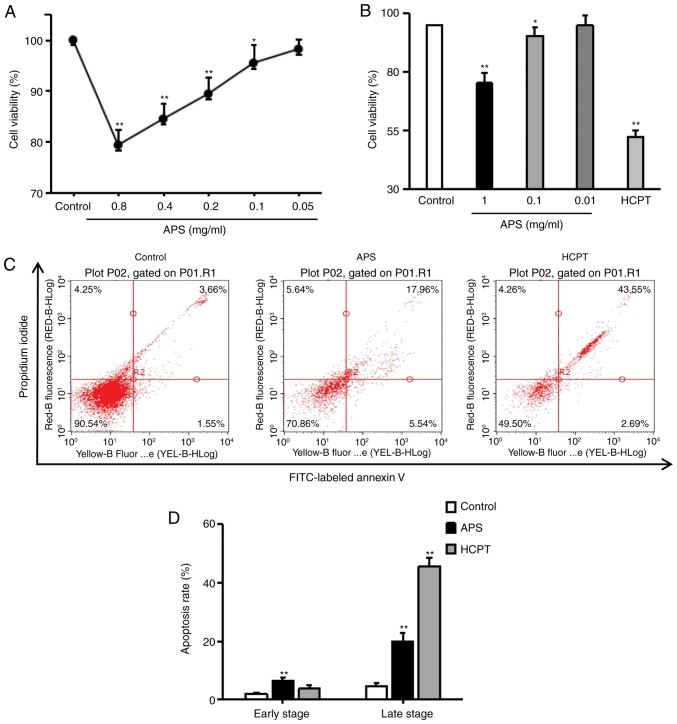

Effects of APS and HCPT on cell viability and apoptosis

To detect the cytotoxic effects of APS, the H1299 cells were exposed to HCPT and varying of doses of APS for 24 h and cell viability was examined using an MTT assay. As with HCPT, APS moderately inhibited the growth and proliferation of H1299 cells (Fig. 2A and B). The effects of APS and HCPT on apoptosis were assessed using an Annexin V-FITC/PI assay. APS significantly enhanced apoptosis in H1299 cells (early apoptosis, 6.48±1.27%; late apoptosis, 19.88±2.89%) and HCPT induced late apoptosis, up to 45.59±2.91% (Fig. 2C and D), indicating that APS and HCPT inhibited cell proliferation by promoting apoptosis in H1299 cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of APS and HCPT on the viability and apoptosis of H1299 cells. Viability of H1299 cells was determined via MTT assay. (A) H1299 cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of APS, and (B) the indicated concentrations of APS or 1 µM HCPT for 24 h. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments. (C) H1299 cells were treated with 0.4 mg/ml APS or 1 µM HCPT for 24 h, and the apoptotic response was analyzed by FACS analysis of Annexin V/propidium iodide double-stained cells. (D) Graph showing the results of apoptisis. Data are representative of two independent experiments. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. untreated control.

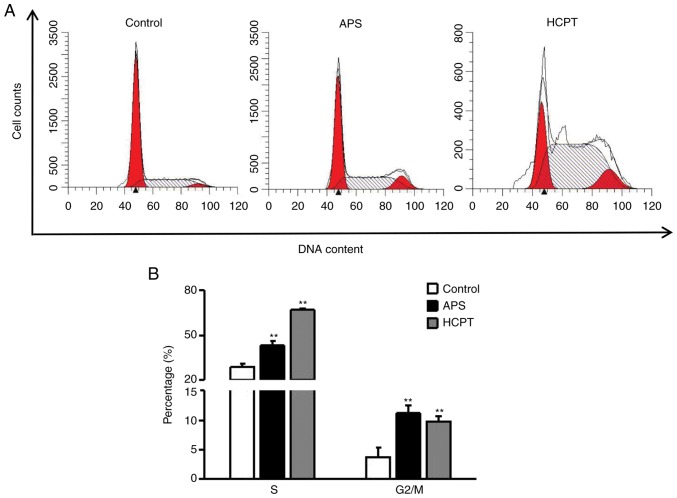

Flow cytometry was used to distinguish between cells in different phases of the cell cycle. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, following APS treatment, the percentages of cells in the S and G2/M phases increased to 42.94±3.09 and 11.12±1.32%, respectively, and following HCPT treatment these proportions were 66.57±2.93 and 9.73±1.39%, respectively, indicating that HCPT and APS treatment induced S phase and G2/M phase arrest. These results further suggested that APS and HCPT induced H1299 cell death by altering the cell cycle distribution.

Figure 3.

Effects of APS and HCPT on cell cycle progression in H1299 cells. (A) Effects of 0.4 mg/ml APS and 1 µM HCPT on cell cycle progression in H1299 cells were analyzed by FACS analysis using propidium iodide single staining. (B) Graph showing results of cell cycle analysis. Data are representative of three independent experiments. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin. **P<0.01, vs. untreated control.

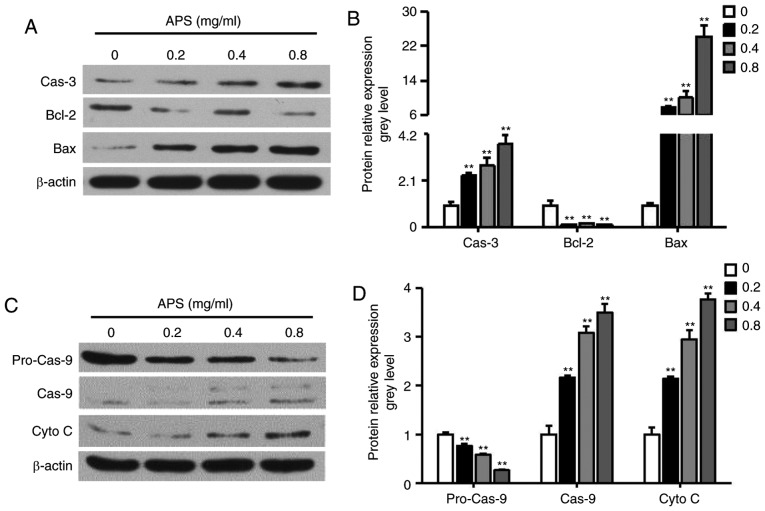

APS induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and HCPT induces autophagy in H1299 cells

The upregulation of caspase-3, cytochrome c and the Bax/Bcl-2 and caspase-9/pro-caspase-9 ratios were observed following treatment of the H1299 cells with APS (Fig. 4A-D). The results indicated that APS treatment induced H1299 cell death through the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria.

Figure 4.

Effects of APS on the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in H1299 cells. H1299 cells were incubated with 0.2-0.8 mg/ml APS for 24 h. (A) Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate levels of Bax, Bcl-2, and Cas-3, with (B) quantification of results shown in the graph. (C) Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate levels of pro-Cas-9, Cas-9 and Cyto C, with (D) quantification of results shown in the graph. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; Cas, caspase; Cyto C, cytochrome c. *P<0.05, vs. control.

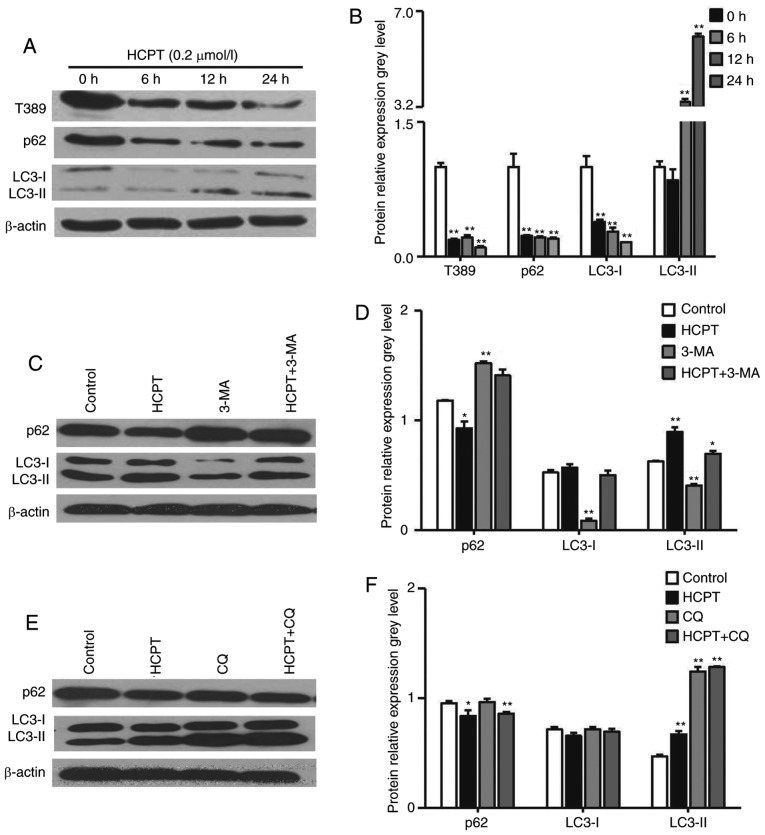

As inhibition of the Akt/mTOR/S6K signaling pathway is linked to the induction of autophagy (23), the present study examined whether HCPT induces autophagy by inhibiting this pathway. Autophagy is activated by the increased expression of LC3-II, which controls the completion of autophagosome formation. P62 is selectively incorporated into autophagosomes through directly binding to LC3 and is efficiently degraded during autophagy. Therefore, the total cellular expression levels of P62 is inversely correlated with the autophagic activity. In the present study, it was demonstrated that HCPT induced the formation of LC3-II and decreased the expression of P62 following treatment with HCPT for 6, 12 and 24 h (Fig. 5A and B). To validate and interpret this result, western blot analysis was performed with the control extracts harvested from cells treated with 3-MA, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, which prevents the induction of autophagosomes and inhibits autophagic flux, and CQ, which inhibits the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes, inhibiting autophagy and leading to LC3 accumulation. Compared with the H1299 cells incubated with HCPT alone, pretreatment with 3-MA markedly decreased the levels of LC3-II and increased the expression of P62 (Fig. 5C and D), whereas pretreatment with CQ markedly increased the levels of LC3-II (Fig. 5E and F), suggesting that HCPT treatment induced autophagic flux.

Figure 5.

HCPT induces autophagy in H1299 cells. H1299 cells were treated with 2 µM HCPT for the indicated times. (A) Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the levels of Thr389-P70S6K, P62, LC3-I/-II and β-actin. β-actin served as a loading control. (B) Graph showing protein expression levels. (C) H1299 cells were pretreated with 5 mM 3-MA for 1 h and incubated with 2 µM HCPT for another 24 h. Levels of P62 and LC3-I and -II were determined and (D) quantified. (E) H1299 cells were pretreated with 20 µM CQ for 1 h and incubated with 2 µM HCPT for another 24 h. P62 and LC3-I and -II levels were determined and (F) quantified. β-actin served as a loading control. Data are representative of three independent experiments. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin; 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; CQ, chloroquine; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. control.

APS and HCPT inhibit the migration and invasion of H1299 cells

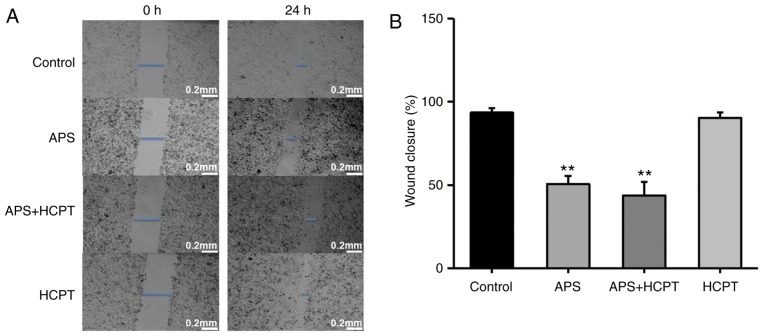

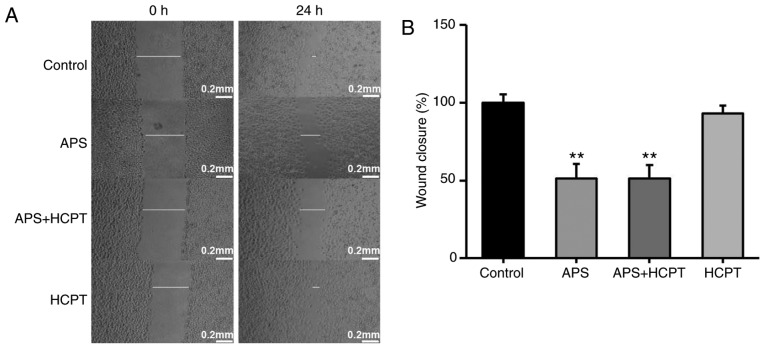

To assess the effect of APS and HCPT on migration and invasion of H1299 cells, a gradual reduction in the area of wounding was observed in the control cells incubated with DMEM for 24 h. Treatment of the H1299 cells with APS resulted in significant inhibition of this migration, whereas HCPT treatment did not affect migration (Fig. 6A and B). The present study further assessed the effect of APS and HCPT on the migration of H460 cells. APS and HCPT affected the migration of H460 cells similar to that of the H1299 cells (Fig. 7A and B).

Figure 6.

APS and combination treatment of APS and HCPT reduce the migration ability of H1299 cells. (A) Migration of H1299 cells with and without treatment with 0.1 mg/ml APS, 0.1 µM HCPT or the combined agents was measured using a wound-healing assay. (B) Quantification of the wound gaps 24 h following induction of the wound. Images were captured using an optical microscope at ×40 magnification. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments, with ten random fields counted in each chamber. Scale bar, 200 µM. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin. **P<0.01, vs. control.

Figure 7.

APS and the combination of APS and HCPT reduce the migration ability of H460 cells. (A) Migration of H460 cells with or without treatment with 0.05 mg/ml APS, 0.2 µM HCPT or the combined agents was measured using a wound-healing assay. (B) Quantification of the wound gaps 24 h following induction of the wound. Images were captured using an optical microscope at a ×40 magnification. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments, with 10 random fields counted in each chamber. Scale bar, 200 µM. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin. **P<0.01 vs. control.

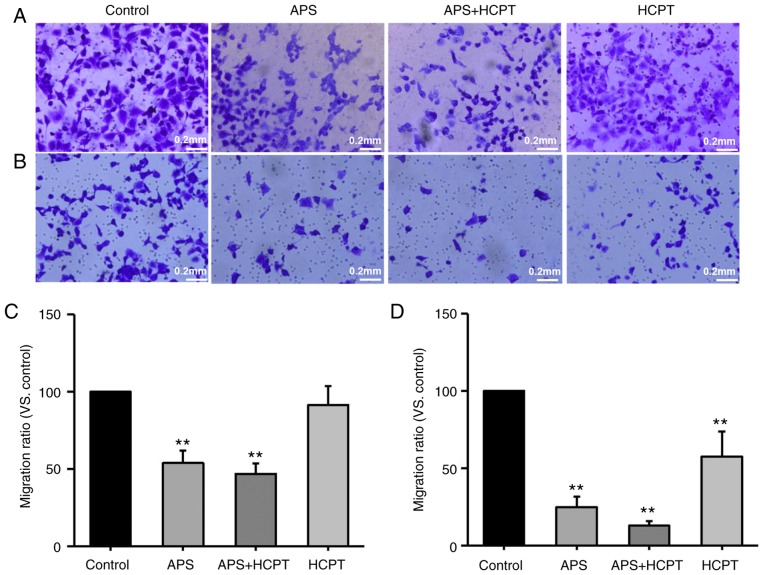

Transwell assays were also performed with polycarbonate filters to analyze the migration and invasion of H1299 (Fig. 8A-D). It was demonstrated that APS and the combination of APS and HCPT inhibited migration by 46.21±7.93 and 53.09±6.7%, respectively, whereas HCPT only had a moderate effect on migration, indicating that treatment with APS and the combined agents inhibited the migration of H1299 cells more effectively than HCPT (Fig. 8A and C). It was also observed that treatment with APS, the combined agents and HCPT inhibited the invasion of H1299 cells by 75.13±6.63, 87.22±3.01 and 42.52±16.36%, respectively, compared with the control, suggesting that the combination of the agents was more effective in inhibiting H1299 migration and invasion compared with APS treatment alone or HCPT alone (Fig. 8B and D).

Figure 8.

A combination of APS and HCPT is most effective at inhibiting the migration and invasion of H1299 cells. (A) Migration and (B) invasion assays were performed following treatment with 0.1 mg/ml APS, 0.1 µM HCPT or the combined agents using a Transwell assay with and without Matrigel. Photomicrographs and bar diagrams of the number of cells that (C) migrated and (D) invaded through the filter to the fibronectin-coated surface following crystal violet staining. Images were captured using an optical microscope at a ×40 magnification. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments with 10 random fields counted for each chamber. Scale bar, 200 µM. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; HCPT, 10-hydroxycamptothecin. **P<0.01 vs. control.

Overexpression of MAP4K3 increases the migration and invasion of H1299 cells, and these effects are reversed by APS treatment

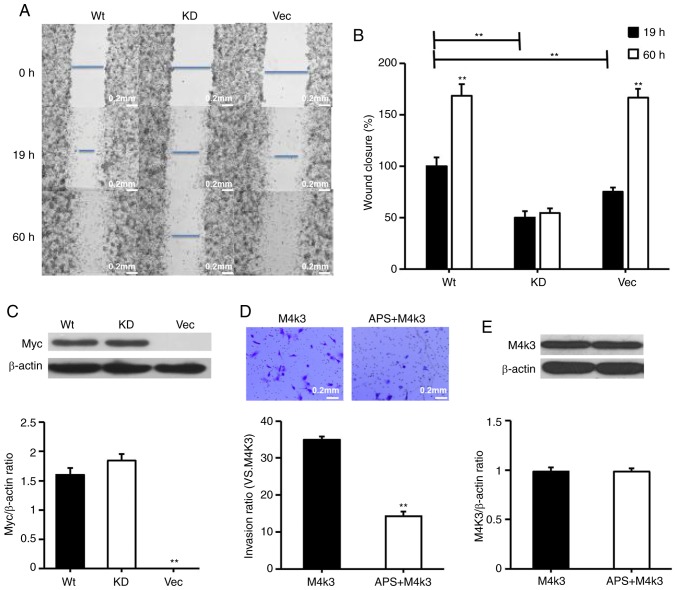

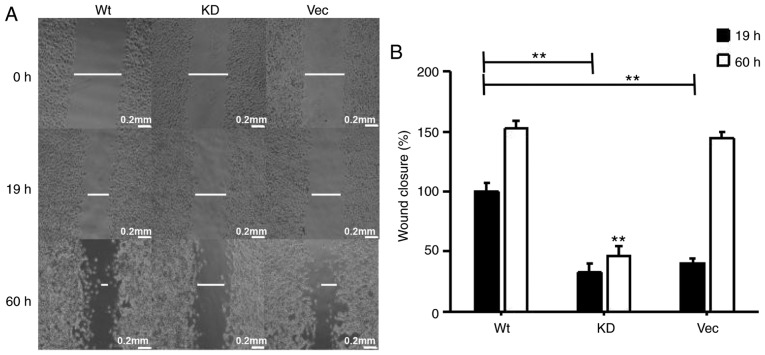

The present study considered whether the overexpression of MAP4K3 stimulates the migration of H1299 cells, despite H1299 exhibit relatively high background expression of MAP4K3. The H1299 cells were transfected with wild-type MAP4K3 and KD MAP4K3, and it was demonstrated that cells transfected with wild-type MAP4K3 led to more rapid closure of the wounded area compared with the cells transfected with KD MAP4K3 or the vector control (Fig. 9A-C). It was also observed that cells transfected with wild-type MAP4K3 and the vector control almost fully reversed the inflicted wound within a 60-h incubation period, whereas the cells transfected with the KD MAP4K3 exhibited decreased migration, suggesting that the KD MAP4K3 behaves like a dominant negative mutation. The results also suggested that, when cells transfected with wild-type MAP4K3 were exposed to APS, their invasive properties were reduced (Fig. 9D and E). The overexpression of MAP4K3 also increased wound closure in the H460 cell line (Fig. 10A and B).

Figure 9.

Overexpression of MAP4K3 increases migration and invasion of H1299 cells and migration and invasion remain sensitive to APS. H1299 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg pRK5myc Vec, 0.5 µg AFG MAP4K3-KD or 0.5 µg pRK5myc M4K3 for 24 h. (A) Images of wound gaps were captured using an optical microscope at a ×40 magnification. (B) Gaps were quantified at 19 and 60 h post-wound induction. (C) Myc levels were determined. (D) H1299 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg pRK5myc M4K3 for 24 h and subsequently incubated for 24 h with or without 0.1 mg/ml APS. Invasion was assessed using Transwell assays with Matrigel. Images were captured using an optical microscope at a ×40 magnification. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments with 10 random fields counted for each chamber. (E) Overexpression of MAP4K3 was determined. β-actin served as a loading control. Scale bar, 200 µM. APS, Astragalus polysaccharide; MAP4K3 or M4K3, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3; Vec, vector; WT, wild-type; KD, kinase-dead. **P<0.01 vs. control.

Figure 10.

Overexpression of MAP4K3 increases the migration of H460 cells. (A) H460 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg pRK5myc Vec, 0.5 µg AFG MAP4K3-KD or 0.5 µg pRK5myc M4K3, and cultured for 24 h. (B) Wound width was quantified at 19 and 60 h following induction of the wound to cell monolayers. Images were captured using an optical microscope at a ×40 magnification. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments with 10 random fields counted for each chamber. Scale bar, 200 µM. MAP4K3 or M4K3, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3; Vec, vector; WT, wild-type; KD, kinase dead. **P<0.01 vs. M4K3 group at 19 h.

Discussion

Traditional Chinese medicines have been considered to be effective in treatment for thousands of years, suggesting that Chinese herbal medicines may serve as suitable candidates in drug development. In the present study, the antitumor effects of commonly used Chinese herbal medicines on H1299 NSCLC cells were screened using an in vitro kinase assay based on the activity of MAP4K3. Two candidates, APS and HCPT, were identified. HCPT was initially used as a positive control in the present study. In previous experiments, HCPT exhibited significant antitumor activity against various tumors, including lung cancer cells, human SMS-KCNR neuroblastoma cells, DU145-TxR prostate cancer cells, and hepatoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma and breast cancer cells (24-29). It was found that HCPT inhibited MAP4K3 kinase activity in vitro and S6K phosphorylation at Thr389 in H1299 cells, however, whether HCPT was able to induce autophagy in H1299 cells remained to be elucidated. Therefore, the expression of autophagy-associated proteins (LC3-I/-II and P62) was assessed, and it was demonstrated that HCPT induced autophagy in H1299 cells by the impairment of MAP4K3/mTOR signaling to S6K. As reported previously for HeLa cells (30), HCPT induced autophagy in H1299 cells.

APS is a mixture of biological macromolecules extracted from Astragalus spp. that exhibits a number of biologically-relevant activities, including potent immunoregulatory properties (31,32), the reduction of chemotoxicity (33) and adverse treatment-associated effects (34,35), and antitumor activities (36). APS can increase the expression of Toll-like receptor 4 to enhance innate immunity during mucosal bacterial infections in vivo and in vitro (37). It has also been used as an adjuvant for an avian infectious bronchitis virus vaccine (38), it inhibits cell volume increases in the myocardium, and has a protective effect on myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury/isoprenaline-treated cardiomyocytes by inhibiting myocardial tissue apoptosis in vivo (39). However, APS treatment inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis in H460 NSCLC cells (36), and combination treatment with vinorelbine and cisplatin administered to patients with advanced NSCLC significantly improved quality of life (40). Astragalus and Salvia miltiorrhiza extract have been shown to inhibit cell migration and invasion in HepG2 cells (41).

The versatile effects of APS on different cell and tissue types in vivo and in vitro explain why the root of Astragalus membranaceus, termed Huang Qi in Mandarin, is one of the most commonly used Chinese herbal medicines. The present study reported that APS induced mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by increasing levels of pro-apoptotic Bax, caspase-3, caspase-9 and cytochrome c, and decreasing levels of Bcl-2 and pro-caspase-9 in H1299 cells. It was also demonstrated that the combination treatment of APS and HCPT was more effective compared with either APS or HCPT treatment alone with respect to inhibiting the migration and invasion of H1299 cells. Furthermore, it was observed that the effects of APS and HCPT treatment on the migration of H460 were similar to those on H1299 cells.

MAP4K3 is a member of the Ste20-related family, named after Sterile 20 involved in pheromone signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (42). Members of this family are characterized by a conserved kinase domain and a noncatalytic region, which enables these proteins to interact with various signaling molecules and regulatory proteins. MAP4K3 promotes cell growth in human HeLa cells in culture in a similar manner to Ras homolog enriched in brain and mTORC1 (43). Therefore, the present study examined MAP4K3 inhibitors as potential tumor-selective therapeutic agents by measuring the inhibition of the kinase in vitro. It was found that APS and HCPT inhibited the activity of MAP4K3 in vitro, particularly HCPT, and the combined agents exhibited more marked suppression of MAP4K3/mTOR signaling to S6K in H1299 cells. It was also demonstrated that the overexpression of wild-type MAP4K3 stimulated wound healing in vitro. Therefore, MAP4K3 may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of NSCLC.

Future preclinical studies may elucidate and supplement the findings of the present study. However, target-based drug screening is a viable approach and mechanism-based combination regimens, including APS and HCPT, may be beneficial in the treatment of NSCLC.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31370764 to LY) and the Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (grant no. ZD2015007 to LY).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Acquisition of data: TH, WL, YZ, LT and JL; analysis and interpretation of data: LY, YZ and TH; statistical analysis: YZ and TH; administrative and technical support: JL and FW; Provision of reagents: XY; drafting of the manuscript: LY; obtained funding: LY. LY conceived and supervised the study, planned experiments, and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Richard F. Lamb at the Section of Cell and Molecular Biology, Chester Beatty Laboratories, Institute of Cancer Research (London, UK), for providing the pRK5mycMAP4K3 and AFG KD MAP4K3 plasmids.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanzaki R, Higashiyama M, Fujiwara A, Tokunaga T, Maeda J, Okami J, Kozuka T, Hosoki T, Hasegawa Y, Takami M, et al. Occult mediastinal lymph node metastasis in NSCLC patients diagnosed as clinical N01 by preoperative integrated FDG-PET/CT and CT: Risk factors, pattern, and histopathological study. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spizzo G, Seeber A, Mitterer M. Routine use of pamidronate in NSCLC patients with bone metastasis: Results from a retrospective analysis. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:5245–5249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidler IJ, Kim SJ, Langley RR. The role of the organ micro-environment in the biology and therapy of cancer metastasis. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:927–936. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiraga M, Yano S, Yamamoto A, Ogawa H, Goto H, Miki T, Miki K, Zhang H, Sone S. Organ heterogeneity of host-derived matrix metalloproteinase expression and its involvement in multiple-organ metastasis by lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5967–5973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen DX, Massagué J. Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:341–352. doi: 10.1038/nrg2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen M, Du Y, Qui M, Wang M, Chen K, Huang Z, Jiang M, Xiong F, Chen J, Zhou J, et al. Ophiopogonin B-induced autophagy in non-small cell lung cancer cells via inhibition of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:430–436. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell. 2017;169:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han B, Cui H, Kang L, Zhang X, Jin Z, Lu L, Fan Z. Metformin inhibits thyroid cancer cell growth, migration, and EMT through the mTOR pathway. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:6295–6304. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Zhang HE, Liu Z. MicroRNA-147 suppresses proliferation, invasion and migration through the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:405–410. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Ding Z, Mo J, Sang B, Shi Q, Hu J, Xie S, Zhan W, Lu D, Yang M, et al. GOLPH3 promotes glioblastoma cell migration and invasion via the mTOR-YB1 pathway in vitro. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:1252–1263. doi: 10.1002/mc.22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai L, Zhuang L, Zhang B, Wang F, Chen X, Xia C, Zhang B. DAG/PKCδ and IP3/Ca2+/CaMK IIβ operate in parallel to each other in PLCγ1-driven cell proliferation and migration of human gastric adenocarcinoma cells, through Akt/mTOR/S6 pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:28510–28522. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Findlay GM, Yan L, Procter J, Mieulet V, Lamb RF. A MAP4 kinase related to Ste20 is a nutrient-sensitive regulator of mTOR signalling. Biochem J. 2007;403:13–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan L, Mieulet V, Burgess D, Findlay GM, Sully K, Procter J, Goris J, Janssens V, Morrice NA, Lamb RF. PP2A T61 epsilon is an inhibitor of MAP4K3 in nutrient signaling to mTOR. Mol Cell. 2010;37:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao B, Han H, Chen J, Zhang Z, Li S, Fang F, Zheng Q, Ma Y, Zhang J, Wu N, Yang Y. MicroRNA let-7c inhibits migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer by targeting ITGB3 and MAP4K3. Cancer Lett. 2014;342:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park J, Lee J, Choi C. Evaluation of drug-targetable genes by defining modes of abnormality in gene expression. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13576. doi: 10.1038/srep13576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu CP, Chuang HC, Lee MC, Tsou HH, Lee LW, Li JP, Tan TH. GLK/MAP4K3 overexpression associates with recurrence risk for non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:41748–41757. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu J, Wang Z, Huang L, Zheng S, Wang D, Chen S, Zhang H, Yang S. Review of the botanical characteristics, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of Astragalus membranaceus (Huangqi) Phytother Res. 2014;28:1275–1283. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Liu F, Yang Y, Li D, Lv J, Ou Y, Sun F, Chen J, Shi Y, Xia P. Astragalus polysaccharide ameliorates ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress in mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;68:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han R. Highlight on the studies of anticancer drugs derived from plants in China. Stem Cells. 1994;12:53–63. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen JJ, Li M, Brinkworth CS, Paulson JL, Wang D, Hübner A, Chou WH, Davis RJ, Burlingame AL, Messing RO, et al. A semisynthetic epitope for kinase substrates. Nat Methods. 2007;4:511–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Che X, Yan H, Sun H, Dongol S, Wang Y, Lv Q, Jiang J. Grifolin induces autophagic cell death by inhibiting the Akt/mTOR/S6K pathway in human ovarian cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:1041–1047. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Zheng Q, Chen W, Wu M, Pan G, Yang K, Li X, Man S, Teng Y, Yu P, Gao W. Chemosensitizing effect of Paris Saponin I on Camptothecin and 10-hydroxycamptothecin in lung cancer cells via p38 MAPK, ERK, and Akt signaling pathways. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;125:760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan ZF, Tang YM, Xu XJ, Li SS, Zhang JY. 10-Hydroxycamptothecin induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SMS-KCNR cells through p53, cytochrome c and caspase 3 pathways. Neoplasma. 2016;63:72–79. doi: 10.4149/neo_2016_009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Z, Zhu G, Getzenberg RH, Veltri RW. The upregulation of PI3K/Akt and MAP kinase pathways is associated with resistance of microtubule-targeting drugs in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116:1341–1349. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallery SR, Shenderova A, Pei P, Begum S, Ciminieri JR, Wilson RF, Casto BC, Schuller DE, Morse MA. Effects of 10-hydroxycamptothecin, delivered from locally injectable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres, in a murine human oral squamous cell carcinoma regression model. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:1713–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Zhang R. Upregulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 in human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 undergoing apoptosis induced by natural product anticancer drugs 10-hydroxycamptothecin and camptothecin through p53-dependent and independent pathways. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:793–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang XW, Qing C, Xu B. Apoptosis induction and cell cycle perturbation in human hepatoma hep G2 cells by 10- hydroxycamptothecin. Anticancer Drugs. 1999;10:569–576. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng YX, Zhang QF, Pan F, Huang JL, Li BL, Hu M, Li MQ, Chen Ch. Hydroxycamptothecin shows antitumor efficacy on HeLa cells via autophagy activation mediated apoptosis in cervical cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37:238–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida Y, Wang MQ, Liu JN, Shan BE, Yamashita U. Immunomodulating activity of Chinese medicinal herbs and Oldenlandia diffusa in particular. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:359–370. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(97)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai X, Xia W, Wei J, Ding X. Therapeutic effect of Astragalus polysaccharides on hepatocellular carcinoma H22-bearing mice. Dose Response. 2017;15:1559325816685182. doi: 10.1177/1559325816685182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassileth BR, Rizvi N, Deng G, Yeung KS, Vickers A, Guillen S, Woo D, Coleton M, Kris MG. Safety and pharmacokinetic trial of docetaxel plus an Astragalus-based herbal formula for non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;65:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1003-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan P, Wang ZM. Clinical study on effect of Astragalus in efficacy enhancing and toxicity reducing of chemotherapy in patients of malignant tumor. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2002;22:515–517. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y, Ruan Y, Shen T, Huang X, Li M, Yu W, Zhu Y, Man Y, Wang S, Li J. Astragalus polysaccharide suppresses doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by regulating the PI3k/Akt and p38MAPK pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014;674219 doi: 10.1155/2014/674219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang JX, Han YP, Bai C, Li Q. Notch1/3 and p53/p21 are a potential therapeutic target for APS-induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung carcinoma cell lines. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:12539–12547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin X, Chen L, Liu Y, Yang J, Ma C, Yao Z, Yang L, Wei L, Li M. Enhancement of the innate immune response of bladder epithelial cells by Astragalus polysaccharides through up regulation of TLR4 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang P, Wang J, Wang W, Liu X, Liu H, Li X, Wu X. Astragalus polysaccharides enhance the immune response to avian infectious bronchitis virus vaccination in chickens. Microb Pathog. 2017;111:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu D, Chen L, Zhao J, Cui K. Cardioprotection activity and mechanism of Astragalus polysaccharide in vivo and in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;111:947–952. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo L, Bai SP, Zhao L, Wang XH. Astragalus polysaccharide injection integrated with vinorelbine and cisplatin for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Effects on quality of life and survival. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1656–1662. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Yang Y, Zhang X, Xu S, He S, Huang W, Roberts MS. Compound Astragalus and Salvia miltiorrhiza extract inhibits cell invasion by modulating transforming growth factor-beta/Smad in HepG2 cell. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leberer E, Dignard D, Harcus D, Thomas DY, Whiteway M. The protein kinase homologue Ste20p is required to link the yeast pheromone response G-protein beta gamma subunits to downstream signalling components. EMBO J. 1992;11:4815–4824. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan L, Lamb RF. Signalling by amino acid nutrients. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:443–445. doi: 10.1042/BST0390443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.