Abstract

Family socioeconomic status (SES) is strongly associated with children’s cognitive development, and past studies have reported socioeconomic disparities in both neurocognitive skills and brain structure across childhood. In other studies, bilingualism has been associated with cognitive advantages and differences in brain structure across the lifespan. The aim of the current study is to concurrently examine the joint and independent associations between family SES and dual-language use with brain structure and cognitive skills during childhood. A subset of data from the Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition and Genetics (PING) study was analyzed; propensity score matching established an equal sample (N = 562) of monolinguals and dual-language users with similar socio-demographic characteristics (M age = 13.5, Range = 3–20 years). When collapsing across all ages, SES was linked to both brain structure and cognitive skills. When examining differences by age group, brain structure was significantly associated with both income and dual-language use during adolescence, but not earlier in childhood. Additionally, in adolescence, a significant interaction between dual-language use and SES was found, with no difference in cortical surface area (SA) between language groups of higher-SES backgrounds but significantly increased SA for dual-language users from lower-SES families compared to SES-matched monolinguals. These results suggest both independent and interacting associations between SES and dual-language use with brain development. To our knowledge, this is the first study to concurrently examine dual-language use and socioeconomic differences in brain structure during childhood and adolescence.

Keywords: bilingualism, dual-language use, socioeconomic status, cognition

Introduction

Approximately 21% of the population in the United States speaks a language other than English at home (U.S. Census, 2015). Studies have reported that bilinguals across the lifespan outperform their monolingual peers on numerous skills, including attention, working memory, inhibition, and memory, among others (for review see Costa & Sebastian-Galles, 2014). Other studies have reported that bilingual individuals demonstrate reliable differences in brain structure (Abutalebi et al, 2012; Della Rosa et al., 2013), brain function (Krizman et al., 2016; Ferjan Ramírez et al., 2016), and even delayed onset of dementia symptoms (Alladi et al., 2013; Gollan et al., 2011) compared to monolingual individuals.

Explanations for these group differences have varied. Some argue that it is the daily experience of managing different languages that leads to enhancements in executive functions (EF), and that better EF improves tasks related to other domains (Bialystok, Craik, & Luk, 2012). Other researchers have emphasized that simply having exposure to multiple languages may differentially affect specific attention and learning mechanisms due to neurocognitive adaptations to early linguistic environments (Brito, Grenell, & Barr, 2015; Costa & Sebastian-Galles, 2014) as robust associations between bilingualism and attention have been reported even during infancy, before EFs have developed (Brito & Barr, 2012; Sebastian-Galles, et al., 2012; Kovacs & Mehler, 2009; Singh et al., 2014).

However, bilingual differences in cognition are not always found, particularly in studies examining executive processing in adults (for review, see Paap & Greenberg, 2013). Some researchers have asserted that the frequently reported differences between monolinguals and bilinguals are the result of publication bias (de Bruin et al., 2015), while others have suggested that such differences are not substantial due to low convergent validity (Paap & Greenberg, 2013). Inconsistent findings may also be based in differences across studies in the types of tasks used or types of bilinguals tested (e.g., age of acquisition, language proficiency, type of exposure/use). Finally, some studies have argued that bilingual advantages are the result of confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status (SES), and that bilingual advantages are attenuated when SES is adequately controlled (Morton & Harper, 2007).

Bilingualism (specifically second language learning) and socioeconomic disadvantage often intersect in the United States; unlike in other industrialized countries, bilingualism is often considered a risk factor for poorer academic outcomes in the U.S. (Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2013), and this risk may more appropriately reflect confounds with SES. As both dual-language use and SES correlate with measures of brain structure and cognition, it is important to examine these experiences independently and as potentially interacting factors.

SES, Cognitive Development, and Brain Development

Childhood socioeconomic status (SES) is commonly characterized by parental educational attainment, parental occupation, or family income (McLoyd, 1998). Socioeconomic disparities have been reported across several neurocognitive domains, with children from higher-SES homes outperforming their peers from lower-SES homes on a variety of tasks, including language and executive functions (Farah et al., 2006; Noble, McCandliss, & Farah, 2007; Sarsour et al., 2011). Several factors may help to explain these SES differences in neurocognitive skills. First, socioeconomically disadvantaged children often experience less linguistic, social, and cognitive stimulation in their home environments compared to their age-matched peers from higher SES homes (Hart & Risley, 1995; Bradley et al., 2001; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). Second, individuals from lower SES households often experience more stressful events during their lifetime, and this higher exposure to stress may be directly related to neurocognitive disparities (Hackman & Farah, 2009; Noble et al., 2012a).

These differences in neurocognitive skills by SES may also be partially explained by differences in brain structure or function (Romeo et al., 2017). For example, Noble and colleagues (2015) analyzed the brain structure of 1,099 children (ages 3 to 20) whose families represented a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Analyses indicated that both family income and parental educational attainment were associated with differences in the total surface area (SA) of the cerebral cortex, but were particularly pronounced in areas of the brain associated with language and executive functioning (e.g., inferior temporal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, and medial prefrontal cortex). SES differences in SA partially mediated the link between SES and executive function skills (inhibitory control and working memory), but not reading or vocabulary skills (Noble et al., 2015).

Socioeconomic disparities in cognitive skills have been reported by 21-months of age (Noble et al., 2015a) and are consistently found across childhood and adolescence (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). However, SES differences in brain structure may differ by age. For example, Piccolo and colleagues (2016) reported that among children from more disadvantaged families, cortical thickness (CT) of the cerebral cortex shows steep age-related differences earlier in childhood, and then levels off during adolescence, with children from more advantaged families showing a more gradual decline in thickness with age. Hanson et al. (2013) reported slower trajectories of cortical volume growth for low-income children, particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes, compared to higher-income children. Notably, these studies did not relate age-related differences in brain structure to differences in behavioral outcomes.

Bilingualism, Cognitive Development and Brain Development

Bilingualism and its associations with cognitive development have been studied since the early 1960s (Pearl & Lambert, 1962). While the mechanisms underlying language processing may vary depending on exposure to one vs. multiple languages, the acquisition of vocabulary and grammar is quite similar for monolinguals and bilinguals (Conboy & Thal, 2006; Hoff et al., 2012). Like monolinguals, language trajectories of bilingual children are associated with the quantity and quality of speech that they hear in each language (Place & Hoff, 2011: Ramirez-Esparza, Garcia-Sierra, & Khul, 2016).

Numerous studies have shown a bilingual advantage on a number of non-linguistic cognitive tasks for infants (e.g., memory generalization [Brito & Barr, 2012]), preschool children (e.g., accuracy on executive function conflict tasks [Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008]), young adults (e.g, accuracy and reaction time on attentional network task [Costa, Hernandez, & Sebastian-Galles, 2008]), and older adults (e.g, accuracy on executive control tasks [Bialystok, Craik, & Luk, 2008). These advantages may reflect differential recruitment of resources as a consequence of the linguistic environment. As both languages are active, bilingual children must accurately select and employ the target language, all while ignoring cues from the competing language system (Bialystok, 2009; Green, 1998). Presumably, parents of bilingual infants do not speak more to their children than parents of monolingual infants. Therefore, bilingual infants must acquire both languages while experiencing reduced input to each one of their languages. This cognitively challenging environment may increase the efficiency to which bilingual children attend to and process stimuli.

Neuroimaging studies have also supported the notion that bilinguals may have more efficient attentional capabilities. Abutalebi and colleagues (2012) reported that bilinguals outperformed monolinguals on a response conflict flanker task and observed decreased activation of the ACC for bilinguals compared to monolinguals during the task, which was interpreted by the authors as more efficient neural processing by bilinguals. Grey matter volume of the ACC was significantly correlated with the functional conflict effect for both language groups but a significant relation between ACC grey matter volume and behavioral data was only present for the for bilingual group – suggesting an association between the bilingual experience, structural brain changes, functional brain activity, and behavior (Abutalebi et al., 2012). Similarly, Della Rosa and colleagues (2013) reported that children who reported higher levels of bilingualism performed more quickly on the incongruent condition of the flanker test; further, increases in grey matter volume in the LIPG over time was positively associated with both the conflict score and level of bilingualism.

Joint Consideration of SES and Bilingualism

Most studies that examine links between bilingualism or dual-language use and cognitive trajectories either control for SES or test participants from the same socioeconomic background. For example, within a sample of children from lower-SES homes, Engel de Abreu, Cruz-Santos, Tourinho, Martin, and Bialystok (2012) compared 8-year-old monolingual children in Portugal with similar children whose parents had emigrated from that region to Luxembourg and were being raised as Portuguese-Luxembourgish bilinguals. Children in both language groups performed comparably on tasks that did not involve executive function, whereas bilingual children performed significantly better than their monolingual counterparts on tasks that included EF demands. Carlson and Meltzoff (2008) compared Spanish-English bilingual children from lower SES homes to monolingual children from middle-SES homes; they found advantages in conflict tasks for the bilinguals, but only once differences in vocabulary scores between the groups were statistically controlled.

Interestingly, a growing number of studies are considering socioeconomic status and dual-language use concurrently. For example, Mezzacappa (2004) reported that children from higher SES homes performed well on most elements of a flanker task; however, Hispanic children from lower SES homes outperformed all other children on incongruent trials, which may require the greatest involvement of EF. Although degree of dual-language use was not formally assessed in this study, two-thirds of the Hispanic children spoke Spanish at home, and the author attributed the difference in scores to bilingualism (Mezzacappa, 2004). Calvo and Bialystok (2014) examined the separate associations of SES and bilingualism with a range of cognitive, linguistic, and executive function tasks among socioeconomically diverse 6- to 7-year-old children. They found that higher SES was associated with higher performance on both language and EF tasks. Although bilingualism was associated with poorer performance on standardized English assessments, bilinguals outperformed monolinguals on executive function tasks. Bilingual children made fewer errors on the flanker task and recalled more items on the working memory task, irrespective of SES level. More recently, Hartanto, Toh, & Yang (2018) examined the links between bilingualism and EF/self-regulatory skills in a sample of 18,200 children (tracked from ages 5 to 7) who represented a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Overall, results indicated that both SES and bilingualism were positively related to EF components (inhibitory control and set shifting) and adaptive self-regulatory behaviors in the classroom, but only SES was associated with verbal working memory. Interestingly, bilingualism also buffered the negative impact of SES on EF skills and self-regulatory behaviors, even after controlling for language proficiency and culture. Finally, Krizman and colleagues (2016) reported more stable neural response (evoked response to the to the consonant-vowel sound ‘da’), stronger phonemic decoding skills, and heightened executive control for bilingual adolescents, regardless of SES. The researchers argue that exposure to multiple languages may provide an enriched linguistic environment that can boost both sensory and cognitive functioning for individuals from both lower- and higher-SES households (Krizman, Skoe, & Kraus, 2016).

Notably, of 11.2 million school-aged bilingual children in the U.S., an estimated 6 million come from poor or near-poor homes (Federal Interagency Forum, 2011). In particular, many bilingual children in the U.S. belong to minority groups of lower social standing; hence, disentangling these two constructs is important when interpreting findings. As experiences of growing up in disadvantaged environments and dual-language exposure have been reported to have substantial associations with development, the current study examines the associations of dual–language use and SES both with brain structure and with cognitive performance, across childhood and adolescence. Although past studies have examined links among SES, dual-language use, and behavioral outcomes, concurrent examination of brain structure is, to our knowledge, a novel approach.

METHOD

Participants

Data used in this study were collected as part of the multi-site Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition, and Genetics (PING) study and obtained from the PING Study database (http://ping.chd.ucsd.edu). Participants were recruited through a combination of web-based, word-of-mouth, and community advertising at nine university-based data collection sites in and around the cities of Los Angeles, San Diego, New Haven, Sacramento, San Diego, Boston, Baltimore, Honolulu, and New York. Participants were excluded if they had a history of neurological, psychiatric, medical, or developmental disorders. In this study, analyses were conducted on 562 participants (281 dual-language users and 281 monolingual participants, matched using propensity score matching [PSM], as discussed below). Participants ranged from 3 to 20 years old (M = 13.5, SD = 4.9). All participants and their parents gave their informed written consent/assent to participate in all study procedures. Each data collection site’s Office of Protection of Research Subjects and Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Measures

Dual-language use

Participants were labeled as dual-language users if they responded ‘Yes’ to the question, “Does the participant speak another language other than English?” Although a coarse measure of degree of bilingualism, this is in line with other research that has found cognitive differences among dual-language users (Mezzacappa, 2004).

Socioeconomic status

Parents were asked to report the level of educational attainment for all parents in the home and total yearly family income. Both parental education and family income data were originally collected in bins, which were recoded as the means of each bin (Noble et al., 2015). The average parental educational attainment was used in all analyses and family income was natural log-transformed due to the typically observed positive skew.

Genetic collection and analysis

A genetic ancestry factor (GAF) was developed for each participant, representing the proportion of ancestral descent for each of six major continental populations: African, Central Asian, East Asian, European, Native American and Oceanic. Information on PING genetic collection and analysis is described in detail in Akshoomoff et al., (2014).

Image acquisition and processing

Each site administered a standardized high-resolution structural MRI (3D T1-weighted scan) protocol (Fjell et al., 2012 for pre- and post-processing techniques information). Image analyses were performed using a modified Freesurfer software suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) to obtain vertex-wise CT (Fischl & Dale, 2000). Neuroimaging data was submitted to a standardized quality-image check, with no manual editing of images that were deemed acceptable (see Jernigan et al., 2016 for details).

Cognitive measures

Performance on vocabulary, reading, working memory, attention/inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility tasks were evaluated using NIH Toolbox® Cognitive Function Battery (Weintraub et al., 2013), as described below.

Picture vocabulary test

This measure of receptive vocabulary was administered in a computerized adaptive format. The participant was presented with an auditory recording of a word and four high-resolution color photos on the computer screen. Then, they were instructed to touch the image that most closely represents the meaning of the auditory word. Each participant was given two practice trials and 25 test trials. Participant performance was converted to a theta score (ranging from −4 to 4), based on item response theory.

Oral reading recognition test

In this reading test, participants were asked to read aloud a word or letter presented on the computer screen. Items were presented in an order of increasing difficulty. Responses were recorded as correct or incorrect by the examiner. In order to assess the full range of reading ability across multiple ages, modifications were made and letters or multiple-choice ‘pre-reading’ items were presented to young children or participants with low literacy levels. The oral reading score ranged from 1 to 281.

List sorting working memory test

This working memory task requires immediate recall and sequencing of visually and orally presented stimuli (Tulsky et al., 2013). Participants were presented with a series of pictures of different animals and food on a computer screen and heard the name of the object from a speaker. The test was divided into the One-List and Two-List conditions. In the One-List condition, participants were told to remember a series of objects (food or animals) and repeat them in order, from smallest to largest. In the Two-List condition, participants were told to remember a series of objects (food and animals, intermixed) and then again report the food in order of size, followed by animals in order of size. Working memory scores consisted of combined total items correct on both conditions, with a max of 28 points.

Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test

The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery version of the flanker task was adapted from the Attention Network Test (ANT) (Rueda et al., 2004). Participants were asked to focus on a given stimulus, presented on the center of a computer screen and were required to indicate the left-right orientation while inhibiting attention to the flankers (surrounding stimuli: fish for ages 3–7 or arrows for ages 8–21). On some trials the orientation of the flankers was congruent with the orientation of the central stimulus and on the other trials the flankers were incongruent. The test consisted of a block of 25 fish trials (designed to be more engaging and easier for children) and a block of 25 arrow trials, with 16 congruent and nine incongruent trials in each block, presented in pseudorandom order. All children age 9 and above received both the fish and arrows blocks regardless of performance. The NIH Toolbox flanker vector score incorporates both the congruent and incongruent trials. A two-vector method was used that incorporated both accuracy and reaction time (RT) for participants who maintained a high level of accuracy (> 80% correct), and accuracy only for those who did not meet this criterion. Each vector score ranged from 0 to 5, for a maximum total score of 10.

Dimensional change card sort cognitive flexibility task

The DCCS is a measure of cognitive flexibility or set shifting. Participants are shown two target pictures, one on each side of the screen, which varies along two dimensions (e.g., shape and color). Participants are asked to match a series of bivalent test pictures (e.g., yellow trucks and red balls) to the target pictures, first according to one dimension (e.g., color) and then, after a number of trials, according to the other dimension (e.g., shape). “Switch” trials are employed in which the participant must change the dimension being matched. For example, after 4 straight trials matching on shape, the participant may be asked to match on color on the next trial and then go back to shape, thus requiring the cognitive flexibility to quickly choose the correct stimulus. Only accuracy was analyzed, with a range of possible scores from 0 to 40.

Analysis Plan

From the full sample of 1091 participants (with data on all relevant independent variables including age, sex, parental educational attainment, family income, genetic ancestry, structural MRI and at least one dependent measure from the NIH Toolbox Cognitive Function Battery), propensity score matching (PSM) was implemented to create a similar distribution of observed covariates between the monolingual and dual-language-exposed groups. A propensity score was calculated via logistic regression model with age, sex, family income, parental educational attainment, and oral reading score as the covariates, as these variables have been reported to be related to differences in brain structure and cognitive skills during childhood within this dataset (Brito, Piccolo, & Noble, 2017; Noble et al., 2015; Piccolo et al., 2016). Reading score was included to rule out the possibility of any structural brain differences being attributed to reading ability (He et al., 2013). Dual-language using children in the sample (N = 281) were matched to monolingual children using one-to-one matching without replacement and nearest neighbor matching criteria (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983; 1985). As matched participants have similar characteristics of interest based on propensity scores, this reduces potential confounds when comparing language groups on measures of brain structure or cognitive scores.

Descriptive statistics and sample sizes for each cognitive variable are shown in Table 2. All measures were normally distributed (+/− 2 values for skewness and kurtosis) and scores from the NIH Toolbox were standardized to allow for comparison across tasks. All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS (version 23). All outcome variables were winsorized to control for outliers, and observations deemed highly influential (using Mahalanobis and Cook’s distances) were excluded from analyses. Associations between SES variables, bilingualism status, cognitive skills, and brain structure controlled for age, age-squared, sex, scanner model and genetic ancestry (GAF). In addition to whole-brain surface area (SA) and cortical thickness (CT), we examined brain regions of interest (ROIs) associated with language (left inferior frontal gyrus [IFG] and left superior temporal gyrus [STG]), as well as ROIs associated with attention and executive function (middle frontal gyrus [MFG; both left and right] and anterior cingulate cortex [ACC]), as these regions have been implicated in past studies of bilingualism and cognition (Abutalebi & Green, 2007; Abutalebi et al., 2012; Luk, Green, Abutalebi, & Grady, 2012; Martensson et al., 2012; Olulade et al., 2016; Ruschemeyer et al., 2005). All multiple comparisons (number of ROIs and cognitive tasks for each domain of interest) were verified using False Discovery Rate (FDR) analyses.

Table 2.

NIH Toolbox Cognitive Measures

| Monolingual | Dual-Language Users | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD; Range) | Mean (SD; Range) | |

|

Vocabulary (n = 545) Picture Vocabulary Test |

1.04 (1.27; −1.86 – 3.77) | 0.92 (1.41; −2.26 – 3.84) |

|

Oral Reading (n = 544) Oral Recognition Test |

145.86 (66.13; 1 – 278) | 144.24 (65.49; 1 – 281) |

|

Working Memory (n = 534) List Sorting Task |

19.30 (3.82; 8 – 28) | 19.15 (3.98; 8 – 27) |

|

Attention & Inhibition (n = 526) Flanker Task |

8.32 (0.98; 4.50 – 9.98) | 8.28 (1.04; 5.03 – 9.90) |

|

Cognitive Flexibility (n = 501) Dimensional Change Card Sort Task |

8.14 (0.98; 5.14 – 10) | 8.11 (1.03; 4.99 – 9.75) |

RESULTS

The final propensity-matched sample included 562 children (254 males) ages 3 to 20 (M = 13.5, SD = 4.9). The sample was also diverse in terms of parental educational attainment, family income, and genetic ancestry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample demographics (N = 562)

| Mean (SD; Range) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 13.47 (4.9; 3.4 – 20.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 254 (45.2%) |

| Female | 308 (54.8%) |

| Dual Language Users | 281 (50%) |

| Parental Education (years) | 15.48 (2.46; 6 – 18) |

| Family Income | $98,540 ($79,582; $4,500 – $325,000) |

| Genetic Ancestry | |

| European | 0.60 (0.38; 0 – 1) |

| East Asian | 0.18 (0.33; 0 – 1) |

| African | 0.11 (0.26; 0 – 1) |

| American Indian | 0.06 (0.14; 0 – 0.83) |

| Central Asian | 0.04 (0.16; 0 – 1) |

| Oceanic | 0.01 (0.03; 0 – 0.25) |

Note. GAF data show mean, standard deviation, and range across all subjects of the estimated proportion of genetic ancestry for each reference population.

Across the full sample, income, but not dual-language use, was associated with total cortical surface area

Controlling for covariates (age, age-squared, sex, GAF, and scanner type), higher family income was significantly related to greater SA (β = 0.14, p < .001, R2= .41), but was not significantly related to CT (p = .76), as has been reported previously in the full PING sample (Noble et al., 2015). In ROI analyses, significant FDR-corrected associations were found between family income and SA in the left IFG (β = 0.10, p = .02, R2= .15) and ACC (β = 0.16, p < .001, R2= .25). Controlling for covariates, parental education was not associated with whole-brain total SA (p = .20) or whole-brain mean CT (p = .69), and no ROIs passed FDR correction. Across the whole group, no significant associations were found between dual-language use and SA or CT, either across the whole brain or in ROIs.

Across the full sample, both income and parental education, but not dual-language use, were associated with cognitive skills

When controlling for covariates (age, age-squared, sex, GAF), higher family income was significantly related to higher vocabulary (β = 0.16, p < .001, R2= .72), reading (β = 0.11, p < .001, R2= .74), working memory (β = 0.16, p < .001, R2= .54), flanker (β = 0.10, p = .001, R2= .58), and DCCS (β = 0.08, p = .01, R2= .62) scores. Higher parental education was also related to higher vocabulary (β = 0.16, p < .001, R2= .72), reading, (β = 0.11, p < .001, R2= .74), working memory (β = 0.12, p < .001, R2= .54), flanker (β = 0.14, p < .001, R2= .59), and DCCS (β = 0.11, p < .001, R2= .63) scores. Across the whole group, no significant associations were found between dual-language use and any of the cognitive measures.

Dual-language use associated with brain structure among adolescents only

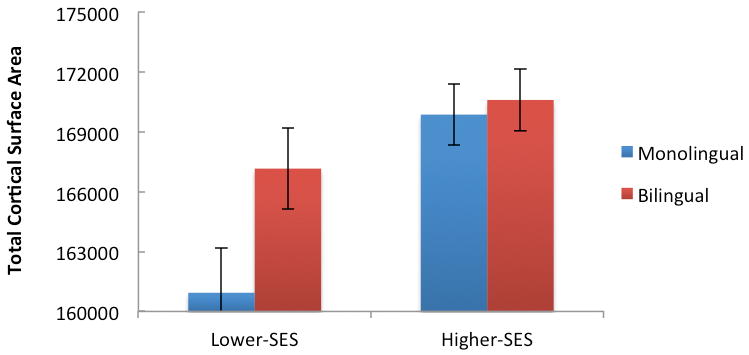

Because brain structure varies dramatically across childhood and adolescence (Brito et al., 2017; Piccolo et al., 2016), we next divided the sample into two age groups: children (ages 3–11.9, M = 8.4, SD = 2.1, N = 237) and adolescents (ages 12 – 20.9, M = 17.2, SD = 2.5, N = 325). Controlling for covariates (sex, GAF, and scanner type), group analysis for the younger children indicated no significant main effects of income (p = .20), or dual-language use (p = .40), and no significant income x dual-language interaction (p = .71) for cortical SA. In contrast, the group analysis for the adolescents indicated both main effects of income (F(1,304) = 12.80, p < .001, η2 = .04) and dual-language use (F(1,304) = 10.11, p = .002, η2 = .03) for cortical SA. Adolescents who reported speaking more than one language had more total SA than their monolingual peers matched for age, sex, SES, and reading ability. Additionally, ROI analyses showed an association among adolescents between dual-language use and SA in the ACC (F(1,302) = 6.36, p = .01, η2 = .02). Furthermore, there was a significant income x dual language interaction on total cortical SA (F(1,304) = 3.94, p = .04, η2 = .01). As shown in Figure 1, the association between dual-language exposure and cortical SA was more pronounced among adolescents from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

Figure 1.

Finally, for younger children, when controlling for covariates (sex and GAF), higher family income was significantly related to higher vocabulary scores (F(1,222) = 7.05, p = .008, η2 = .02). For adolescents, when controlling for covariates, higher income was significantly related to higher vocabulary (F(1,303) = 7.35, p = .007, η2 = .02), reading (F(1,304) = 8.20, p = .004, η2 = .023), working memory (F(1,307) = 17.49, p < .001, η2 = .05), and flanker (F(1,313) = 7.38, p = .007, η2 = .02) scores. No significant associations were found between dual-language use and any of the cognitive measures when the sample was broken down by age.

Discussion

Past studies have demonstrated that family SES and exposure to multiple languages are each associated with differences in brain structure and cognitive skills. Robust SES differences have been found across several neurocognitive domains throughout childhood (Farah et al., 2006; Noble, McCandliss, & Farah, 2007), and these associations between SES and cognitive skills may be partially mediated by differences in brain structure (Noble et al., 2015b). Variations in cognitive skills and brain structure have also been attributed to dual-language exposure (see Bialystok, 2017), but bilingual differences are not always found (de Bruin, Treccani, & Sala, 2015; Paap & Greenberg, 2013). Importantly, most studies have failed to stratify participants by both SES and bilingualism levels when examining divergences in brain structure and cognitive skills.

The current study examined the joint and independent associations of both dual-language use and SES with brain structure and cognitive performance during childhood. Across the full sample (ages 3.0 to 20.9), SES, but not dual-language use, was related to both brain structure (total SA & left IFG) and all cognitive skills of interest. When examining associations separately by age groups, a different pattern emerged. For younger children (ages 3.0 to 11.9), income was associated with language skills (vocabulary), but there were no significant associations between income and brain structure. Dual-language use for younger children was unrelated to either brain structure or cognitive skills. In contrast, for adolescents (ages 12.0 to 20.9), there was a robust association between both SES and brain structure (total SA & ACC) as well as dual-language use and brain structure (total SA & ACC). Additionally, there was a significant interaction between SES and dual-language use, such that the association between dual-language use and brain structure was most pronounced among adolescents from more disadvantaged families. Finally, for adolescents, SES was significantly related to most cognitive skills of interest, though there was no relation between dual-language use and cognitive skills.

In sum, across childhood we find consistent associations between SES and both brain and cognitive outcomes, but fewer associations between dual-language exposure and these outcomes. Further, the associations between both SES and dual-language exposure with brain structure and cognition were more pronounced in adolescence as compared to earlier in childhood. As shown in Figure 1, SES and dual-language status interacted in their contribution to differences in brain structure for adolescents.

It is notable that, unlike in past studies (Della Rosa et al., 2013; Hanson et al., 2013; Noble et al., 2012), we did not find robust associations between either SES or dual-language exposure and brain structure within the younger cohort (ages 3–11.9). We suggest three factors that may have contributed to these discrepancies.

First, the younger cohort (N = 237) had fewer matched participants than the older cohort (N = 325). This could have led to the model being underpowered to detect small associations at the younger ages.

Second, differences in findings across studies may be due to differences in the techniques used to measure morphometry. Past studies have most commonly reported gray matter volumes (total and ROIs), and not cortical surface area, as the outcome of interest. Cortical volume is a composite measure of both cortical surface area and cortical thickness, which are genetically and phenotypically independent structures. Cross-sectional comparisons of cortical volume may be a poorer indicator of brain maturation (Giedd and Rapoport, 2010) and predictors of surface area and cortical thickness may be better at accounting for individual differences in cognitive abilities.

Finally, the crude measure of dual-language exposure available in the PING dataset (i.e., whether the participants responded ‘Yes’ to the question, “Does the participant speak another language other than English?”) may have contributed to the lack of language exposure effects among younger children. This question reflects a binary categorical variable and does not account for type of exposure (e.g., dual language within the home vs. minority language within home and majority language within school/community), amount of exposure, proficiency (e.g., balanced vs. unbalanced bilingualism), or age of second language acquisition (early acquisition vs. later acquisition). These facets of bilingualism have been reported to impact both brain and behavioral findings (Archila-Suerte, Zevin, & Hernandez, 2015; Hoff, et al., 2014; Thomas-Sunesson, Hakuta, & Bialystok, 2016; Winsler et al., 2014). Age of acquisition (AoA) in particular has been strongly associated with both behavioral differences (Luk, de Sa & Bialystok, 2011; Sebastián-Gallés, Echeverría, & Bosch, 2005) and underlying neural correlates (Klein, et al., 2014; Mohades, et al., 2012; 2015) related to bilingualism, and has been reported to be a better predictor of bilingual brain-behavior correlations than proficiency or exposure (Archila-Suerte et al., 2015; Sebastian-Galles et al., 2005; Yow & Li, 2015). Unlike the binary measure of dual language exposure, the SES measures included here (i.e., income and education) were measured as continuous variables, allowing for more variability between individuals and a higher probability of finding significant associations with both brain and cognitive outcomes. Additionally, as the dual-language question itself asks whether or not the participant “speaks” another language besides English, it may have been easier to assess whether or not a second language was spoken by the participant for adolescents vs. younger children – possibly leading to less variability for the younger monolingual cohort and contributing to null effects.

Our results are consistent with past studies demonstrating robust associations between family SES and cognitive skills, particularly language. Socioeconomic disparities have been frequently associated with differences in verbal ability, as well as with differences in executive functioning (Brito & Noble, 2014). This may be due in part to differences in exposure to complex, responsive language within the home (Hart & Risely, 1995; Melvin et al., 2015), and differences in exposure to family stress (Blair et al., 2011). We also found differential links between brain structure and family income vs. parental education; it has been suggested that these SES factors have differential associations with child development (Duncan & Magnuson, 2012; Duncan, Magnuson, & Votruba-Drzal, 2014). Education may influence the quantity and quality of cognitive stimulation within the home, whereas income may be more strongly related to the material resources available (Duncan et al., 2014). These differences may manifest distinctly upon brain and cognitive trajectories and therefore these indices of SES should be evaluated separately to understand possible pathways through which socioeconomic disparities in development emerge.

It is notable that differences in adolescent brain structure were found as a function of dual-language exposure, even with such a simple measure of dual-language use, even when concurrently considering socioeconomic background. Consistent with past studies, differences as a function of language exposure were observed in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which serves to support conflict monitoring abilities (Abutalebi et al., 2012). Furthermore, the interaction between dual-language use and SES suggests that the positive correlation between exposure to multiple languages and cortical SA was more pronounced among children from disadvantaged backgrounds. One possibility is that exposure to multiple languages may in part buffer against some of the risk conferred by socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., Hartanto et al., 2018), though the mechanism underlying this finding remains to be investigated.

Both SES and dual-language exposure exhibited more pronounced associations with outcomes in adolescence, suggesting that duration of exposure may play a role. Though not directly measured here, one possible explanation for the unique role of dual-language use in adolescence may be related to differences in the AoA of the second language. Past work has reported that AoA is related to cortical thickness in sequential bilinguals only – that is, bilinguals who learned their second language after their first (Klein et al. 2014). Specifically, sequential bilinguals demonstrated a thicker left inferior frontal cortex compared to simultaneous bilinguals (i.e., bilinguals who learned both languages at roughly the same time) or monolinguals (Klein et al. 2014), but no structural differences were found between monolinguals and simultaneous bilinguals, suggesting that acquiring a second language after infancy may produce specific structural changes in brain areas associated with language, and using or switching between two languages may require more effort for sequential bilinguals (Klein et al., 2014). If we were to speculate that the younger dual-language users may be more likely to include simultaneous bilinguals and the older dual-language users may be more likely to include sequential bilinguals, then the difference in findings by age presented in the current study could be similar to the results of Klein and colleagues (2014), who suggested that that specific structural changes in the brain may be due to increased effort required by sequential bilinguals to monitor and control their two language systems.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to concurrently examine dual-language use and socioeconomic differences in brain structure during childhood. Further, through the use of propensity score matching, we took great care to match monolinguals and dual-language users on a host of observed covariates, improving our ability to draw causal inferences regarding the effect of dual-language use on brain structure and cognition.

Nonetheless, this study is not without its limitations. Within the confines of a large dataset of childhood brain and cognitive measures, our measure of dual-language use was coarse. Future studies should include more refined measures of bilingualism. Additionally, even with large sample sizes, cross-sectional studies allow for limited interpretations regarding developmental trajectories. Variations in brain structure due to SES or bilingualism may reflect experiential discrepancies in exposures (e.g., language, stress), and a longitudinal study would be necessary to more accurately examine changes in brain structure over time. Moreover, despite rigorous statistical control of numerous variables, we cannot directly infer that more or less surface area in regions identified within this study is necessarily caused by our variables of interest.

The brain demonstrates a remarkable capacity to undergo structural and functional change in response to experience throughout the lifespan. Language use is an intense and sustained experience that engages multiple regions of the brain (Friederici, 2011), and exposure to multiple languages has robust consequences for many aspects of children’s brain and cognitive development. Disentangling the independent and interacting associations between SES, bilingualism and cognitive development is crucial for identifying mechanisms of risk and resilience, and possible interventions, for lower SES minority children.

Research Highlights.

Across all ages, socioeconomic status (SES) but not dual-language use was associated with brain structure and cognitive skills during childhood.

During adolescence, an interaction between dual-language use and SES was observed; the association between dual-language and brain structure was more pronounced at lower levels of SES.

This is the first study to concurrently examine dual-language use and socioeconomic differences in brain structure during childhood and adolescence.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the Sackler Parent-Infant Project Fellowship to NHB. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition and Genetics Study (PING) (National Institutes of Health Grant RC2DA029475). PING is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. PING data are disseminated by the PING Coordinating Center at the Center for Human Development, University of California, San Diego.

References

- Abutalebi J, Della Rosa PA, Green DW, Hernandez M, Scifo P, Keim R, … Costa A. Bilingualism tunes the anterior cingulate cortex for conflict monitoring. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22(9):2076–2086. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abutalebi J, Green D. Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language representation and control. Journal of neurolinguistics. 2007;20(3):242–275. [Google Scholar]

- Akshoomoff N, et al. The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery: results from a large normative developmental sample (PING) Neuropsychology. 2014;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/neu0000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alladi S, Bak TH, Duggirala V, Surampudi B, Shailaja M, Shukla AK, … Kaul S. Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology. 2013;81(22):1938–1944. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436620.33155.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DH, Lange K. Enhancements to the ADMIXTURE algorithm for individual ancestry estimation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NB, Armstead CA. Toward understanding the association of socioeconomic status and health: A new challenge for the biopsychosocial approach. Psychosomatic medicine. 1995;57(3):213–225. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archila-Suerte P, Zevin J, Hernandez AE. The effect of age of acquisition, socioeducational status, and proficiency on the neural processing of second language speech sounds. Brain and language. 2015;141:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40(3):373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. Cognitive complexity and attentional control in the bilingual mind. Child development. 1999;70(3):636–644. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2009;12(1):3–11. doi: 10.1017/S1366728908003477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. The bilingual adaptation: How minds accommodate experience. Psychological bulletin. 2017;143(3):233. doi: 10.1037/bul0000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Barac R. Emerging bilingualism: Dissociating advantages for metalinguistic awareness and executive control. Cognition. 2012;122(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FI, Luk G. Lexical access in bilinguals: Effects of vocabulary size and executive control. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2008;21(6):522–538. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Martin MM. Attention and inhibition in bilingual children: Evidence from the dimensional change card sort task. Developmental science. 2004;7(3):325–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Martin MM, Viswanathan M. Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. International Journal of Bilingualism. 2005;9(1):103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Luk G, Peets KF, Yang S. Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13(04):525–531. doi: 10.1017/S1366728909990423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Shapero D. Ambiguous benefits: The effect of bilingualism on reversing ambiguous figures. Developmental Science. 2005;8(6):595–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, Burchinal M, McAdoo HP, García Coll C. The home environments of children in the United States Part II: Relations with behavioral development through age thirteen. Child development. 2001;72(6):1868–1886. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual review of psychology. 2002;53(1):371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito N, Barr R. Influence of bilingualism on memory generalization during infancy. Developmental Science. 2012;15(6):812–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.1184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito NH, Grenell A, Cuppari R, Nugent C, Barr R. Specificity In The Bilingual Advantage For Memory During Infancy. Developmental Psychobiology. 2015;57:S5. [Google Scholar]

- Brito NH, Piccolo LR, Noble KG. Associations between cortical thickness and neurocognitive skills during childhood vary by family socioeconomic factors. Brain and Cognition. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo A, Bialystok E. Independent effects of bilingualism and socioeconomic status on language ability and executive functioning. Cognition. 2014;130(3):278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Meltzoff AN. Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science. 2008;11(2):282–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy BT, Mills DL. Two languages, one developing brain: Event-related potentials to words in bilingual toddlers. Developmental science. 2006;9(1):F1–F12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy BT, Thal DJ. Ties Between the Lexicon and Grammar: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Studies of Bilingual Toddlers. Child development. 2006;77(3):712–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Sebastian-Galles N. How does the bilingual experience sculpt the brain? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2014;15:336–345. doi: 10.1038/nrn3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Hernández M, Sebastián-Gallés N. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition. 2008;106(1):59–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin A, Treccani B, Della Sala S. Cognitive advantage in bilingualism: An example of publication bias? Psychological Science. 2015;26:99–107. doi: 10.1177/0956797614557866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Rosa PA, Videsott G, Borsa VM, Canini M, Weekes BS, Franceschini R, Abutalebi J. A neural interactive location for multilingual talent. Cortex. 2013;49(2):605–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra T, Grainger J, Van Heuven WJ. Recognition of cognates and interlingual homographs: The neglected role of phonology. Journal of Memory and Language. 1999;41(4):496–518. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1999.2654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K. Socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning: moving from correlation to causation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2012;3(3):377–386. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K, Votruba-Drzal E. Boosting family income to promote child development. The Future of Children. 2014;24(1):99–120. doi: 10.1353/foc.2014.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel de Abreu PM, Cruz-Santos A, Tourinho CJ, Martin R, Bialystok E. Bilingualism enriches the poor: Enhanced cognitive control in low-income minority children. Psychological science. 2012;23(11):1364–1371. doi: 10.1177/0956797612443836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ, Shera DM, Savage JH, Betancourt L, Giannetta JM, Brodsky NL, … Hurt H. Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain research. 2006;1110(1):166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ, Shera DM, Savage JH, Betancourt L, Giannetta JM, Brodsky NL, … Hurt H. Childhood poverty: specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain Research. 2006;1110(1):166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children: Key national indicators of well-being. 2011 Retrieved from http://childstats.gov/americaschildren/index.asp.

- Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(20):11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Brown TT, Kuperman JM, Chung Y, Hagler DJ, … Akshoomoff N. Multimodal imaging of the self-regulating developing brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(48):19620–19625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208243109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD. The brain basis of language processing: from structure to function. Physiological reviews. 2011;91(4):1357–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbin G, Sanjuan A, Forn C, Bustamante JC, Rodríguez-Pujadas A, Belloch V, … Ávila C. Bridging language and attention: brain basis of the impact of bilingualism on cognitive control. Neuroimage. 2010;53(4):1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Structural MRI of pediatric brain development: what have we learned and where are we going? Neuron. 2010;67(5):728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Salmon DP, Montoya RI, Galasko DR. Degree of bilingualism predicts age of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in low-education but not in highly educated Hispanics. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(14):3826–3830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DW. Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 1998;1:67–81. doi: 10.1017/S1366728998000133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan A, Jones ŌP, Ali N, Crinion J, Orabona S, Mechias ML, … Price CJ. Structural correlates for lexical efficiency and number of languages in non-native speakers of English. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(7):1347–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman DA, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13(2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Hair N, Shen DG, Shi F, Gilmore JH, Wolfe BL, et al. Family poverty affects the rate of human infant brain growth. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartanto A, Toh WX, Yang H. Bilingualism Narrows Socioeconomic Disparities in Executive Functions and Self-Regulatory Behaviors During Early Childhood: Evidence From the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. Child Development. 2018 doi: 10.1111/cdev.13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Xue G, Chen C, Chen C, Lu ZL, Dong Q. Decoding the neuroanatomical basis of reading ability: a multivoxel morphometric study. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:12835–12843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0449-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AE, Li P. Age of acquisition: Its neural and computational mechanisms. Psychological bulletin. 2007;133(4):638. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Core C. Seminars in speech and language. 04. Vol. 34. Thieme Medical Publishers; 2013. Nov, Input and language development in bilingually developing children; pp. 215–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Core C, Place S, Rumiche R, Señor M, Parra M. Dual language exposure and early bilingual development. Journal of child language. 2012;39(01):1–27. doi: 10.1017/S0305000910000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Welsh S, Place S, Ribot K, Grüter T, Paradis J. Properties of dual language input that shape bilingual development and properties of environments that shape dual language input. Input and experience in bilingual development. 2014;13:119. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical research memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Mok K, Chen JK, Watkins KE. Age of learning shapes brain structure: A cortical thickness study of bilingual and monolingual individuals. Brain and Language. 2014;131:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács ÁM, Mehler J. Flexible learning of multiple speech structures in bilingual infants. Science. 2009;325(5940):611–612. doi: 10.1126/science.1173947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizman J, Skoe E, Kraus N. Bilingual enhancements have no socioeconomic boundaries. Developmental science. 2016;19(6):881–891. doi: 10.1111/desc.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk G, Green DW, Abutalebi J, Grady C. Cognitive control for language switching in bilinguals: A quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2012;27(10):1479–1488. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2011.613209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk G, De Sa ERIC, Bialystok E. Is there a relation between onset age of bilingualism and enhancement of cognitive control? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2011;14(04):588–595. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey AP, Finn AS, Leonard JA, Jacoby-Senghor DS, West MR, Gabrieli CF, Gabrieli JD. Neuroanatomical correlates of the income-achievement gap. Psychological Science. 2015;26(6):925–933. doi: 10.1177/0956797615572233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson J, Eriksson J, Bodammer NC, Lindgren M, Johansson M, Nyberg L, Lovden M. Growth of language-related brain areas after foreign language learning. NeuroImage. 2012;63:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American psychologist. 1998;53(2):185. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechelli A, Crinion JT, Noppeney U, O’doherty J, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, Price CJ. Neurolinguistics: structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature. 2004;431(7010):757–757. doi: 10.1038/431757a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin SA, Brito NH, Mack LJ, Engelhardt LE, Fifer WP, Elliott AJ, Noble KG. Home environment, but not socioeconomic status, is linked to differences in early phonetic perception ability. Infancy. 2017;22(1):42–55. doi: 10.1111/infa.12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E. Alerting, orienting, and executive attention: Developmental properties and sociodemographic correlates in an epidemiological sample of young, urban children. Child development. 2004;75(5):1373–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohades SG, Struys E, Van Schuerbeek PV, Mondt K, Van de Craen P, Luypaert R. DTI reveals structural differences in white matter tracts between bilingual and monolingual children. Brain Research. 2012;1435:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohades SG, Van Schuerbeek P, Rosseel Y, Van De Craen P, Luypaert R, Baeken C. White-matter development is different in bilingual and monolingual children: a longitudinal DTI study. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0117968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton JB, Harper SN. What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Developmental science. 2007;10(6):719–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Norman MF, Farah MJ. Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Developmental science. 2005;8(1):74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Engelhardt LE, Brito NH, Mack LJ, Nail EJ, Angal J, Barr R, Fifer WP, Elliott AJ in collaboration with the PASS Network. Socioeconomic disparities in neurocognitive development in the first two years of life. Developmental psychobiology. 2015a;57(5):535–551. doi: 10.1002/dev.21303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NB, Bartsch H, Kan E, Kuperman JM, Akshoomoff N, Amaral DG, Bloss CS, Libiger O, Schork NJ, Murray SS, Casey BJ, Chang L, Ernst TM, Frazier JA, Gruen JR, Kennedy DN, Van Zijl P, Mostofsky S, Kaufmann WE, Keating BG, Kenet T, Dale AM, Jernigan TL, Sowell ER for the Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition and Genetics Study. Family income, parental education and brain development in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience. 2015b;18(5):773–778. doi: 10.1038/nn.3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Houston SM, Kan E, Sowell ER. Neural correlates of socioeconomic status in the developing human brain. Developmental Science. 2012a;15(4):516–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, McCandliss BD, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science. 2007;10(4):464–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers RE, editors. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Vol. 2. Multilingual Matters; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Olulade OA, Jamal NI, Koo DS, Perfetti CA, LaSasso C, Eden GF. Neuroanatomical evidence in support of the bilingual advantage theory. Cerebral Cortex. 2016;26:3196–3204. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paap KR, Greenberg ZI. There is no coherent evidence for a bilingual advantage in executive processing. Cognitive Psychology. 2013;66:232–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl E, Lambert WE. The relations of bilingualism to intelligence. Psychological Monograph. 1962;76 (Serial No. 546) [Google Scholar]

- Pelham SD, Abrams L. Cognitive advantages and disadvantages in early and late bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2014;40(2):313. doi: 10.1037/a0035224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perani D, Abutalebi J. The neural basis of first and second language processing. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2005;15(2):202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo LR, Merz EC, He X, Sowell ER, Noble KG. Age-Related Differences in Cortical Thickness Vary by Socioeconomic Status. PloS one. 2016;11(9):e0162511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place S, Hoff E. Properties of dual language exposure that influence 2-year-olds’ bilingual proficiency. Child development. 2011;82(6):1834–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin-Dubois D, Blaye A, Coutya J, Bialystok E. The effects of bilingualism on toddlers’ executive functioning. Journal of experimental child psychology. 2011;108(3):567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferjan Ramírez N, Ramírez RR, Clarke M, Taulu S, Kuhl PK. Speech discrimination in 11-month-old bilingual and monolingual infants: a magnetoencephalography study. Developmental Science. 2017;20(1) doi: 10.1111/desc.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Shin HS, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D, Pentz MA. Prospective associations between bilingualism and executive function in Latino children: Sustained effects while controlling for biculturalism. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014;16(5):914–921. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. The American Statistician. 1985;39(1):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR, et al. Development of attentional networks in childhood. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(8):1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüschemeyer SA, Fiebach CJ, Kempe V, Friederici AD. Processing lexical semantic and syntactic information in first and second language: fMRI evidence from German and Russian. Human brain mapping. 2005;25(2):266–286. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarsour K, Sheridan M, Jutte D, Nuru-Jeter A, Hinshaw S, Boyce WT. Family socioeconomic status and child executive functions: The roles of language, home environment, and single parenthood. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2011;17:120–132. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián-Gallés N, Albareda-Castellot B, Weikum WM, Werker JF. A bilingual advantage in visual language discrimination in infancy. Psychological Science. 2012;23(9):994–999. doi: 10.1177/0956797612436817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián-Gallés N, Echeverría S, Bosch L. The influence of initial exposure on lexical representation: Comparing early and simultaneous bilinguals. Journal of Memory and Language. 2005;52(2):240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Singh L, Fu CS, Rahman AA, Hameed WB, Sanmugam S, Agarwal P, … Rifkin-Graboi A. Back to basics: a bilingual advantage in infant visual habituation. Child development. 2015;86(1):294–302. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Federspiel A, Koenig T, Wirth M, Strik W, Wiest R, … Dierks T. Structural plasticity in the language system related to increased second language proficiency. Cortex. 2012;48(4):458–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco A, Yamasaki B, Natalenko R, Prat CS. Bilingual brain training: A neurobiological framework of how bilingual experience improves executive function. The International Journal of Bilingualism. 2014;18:67–92. doi: 10.1177/1367006912456617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Sunesson D, Hakuta K, Bialystok E. Degree of bilingualism modifies executive control in Hispanic children in the USA. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2016.1148114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulsky DSV, et al. NIH toolbox cognition battery (CB): measuring working memory. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2013;78(4):70–87. doi: 10.1111/mono.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census Data Results. 2015 < http://2015.census.gov/2015census/>.

- Weintraub S, Dikman SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ, … Gershon R. Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80(Suppl 3):S54– 64. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsler A, Burchinal MR, Tien HC, Peisner-Feinberg E, Espinosa L, Castro DC, … De Feyter J. Early development among dual language learners: The roles of language use at home, maternal immigration, country of origin, and socio-demographic variables. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2014;29(4):750–764. [Google Scholar]

- Yow WQ, Li X. Balanced bilingualism and early age of second language acquisition as the underlying mechanisms of a bilingual executive control advantage: why variations in bilingual experiences matter. Frontiers in psychology. 2015;6:164. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Abutalebi J, Zinszer B, Yan X, Shu H, Peng D, Ding G. Second language experience modulates functional brain network for the native language production in bimodal bilinguals. NeuroImage. 2012;62(3):1367–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]