Abstract

Objective

Under US law, tobacco product marketing may claim lower exposure to chemicals, or lower risk of health harms, only if these claims do not mislead the public. We sought to examine the impact of such marketing claims about potential modified risk tobacco products (MRTPs).

Methods

Participants were national samples of 4797 adults and 969 adolescent US smokers and non-smokers. We provided information about a potential MRTP (heated tobacco product, electronic cigarette or snus). Experiment 1 stated that the MRTP was as harmful as cigarettes or less harmful (lower risk claim). Experiment 2 stated that the MRTP exposed users to a similar quantity of harmful chemicals as cigarettes or to fewer chemicals (lower exposure claim).

Results

Claiming lower risk led to lower perceived quantity of chemicals and lower perceived risk among adults and adolescents (all p<0.05, Experiment 1). Among adults, this claim led to higher susceptibility to using the MRTP (p<0.05). Claiming lower exposure led to lower perceived chemical quantity and lower perceived risk (all p<0.05), but had no effect on use susceptibility (Experiment 2). Participants thought that snus exposed users to more chemicals and was less safe to use than heated tobacco products or electronic cigarette MRTPs (Experiments 1 and 2).

Discussion

Risk and exposure claims acted similarly on MRTP beliefs. Lower exposure claims misled the public to perceive lower perceived risk even though no lower risk claim was explicitly made, which is impermissible under US law.

Keywords: public policy, advertising and promotion, packaging and labelling

Introduction

Attempts to market products as safer alternatives to conventional cigarettes or as smoking cessation tools date back to the 1950s. The tobacco industry aimed to appeal to health-conscious consumers1 and respond to declining cigarette smoking rates2 3 attributable to tobacco control efforts (eg, smoke-free laws, media campaigns, taxation)4 and growing antismoking norms.5 Some tobacco companies made claims that their tobacco products cause less harm or deliver lower levels of chemicals than conventional cigarettes. For example in the early 2000s, Brown & Williamson advertised their Advance Lights as ‘A step in the right direction. All of the taste … Less of the toxins’6 and Vector claimed their Omni cigarettes to be ‘The only cigarette to significantly reduce carcinogens that are among the major causes of lung cancer’.7 More recently, electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) marketing has often claimed e-cigarettes to be safer than combusted cigarettes.8–10 Such advertising claims of reduced exposure to harmful chemicals and reduced risk of harm lower public perceptions of harm and increase willingness to try these products.11–17

After decades of misleading reduced risk claims,18 the 2009 US Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act) provided a regulatory framework in which tobacco companies could introduce and market tobacco products with lower exposure or risk claims only after a review and obtaining a marketing order from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).19 Under the law, products with these claims are ‘modified risk tobacco products’ (MRTPs), defined as products ‘sold or distributed for use to reduce harm or the risk of tobacco-related disease associated with commercially marketed tobacco products.’20

According to US law, applicants for MRTP status can qualify through one of two legal pathways.21 For the first pathway, a manufacturer can qualify by demonstrating that the product, as used by consumers, lowers harm or risk of tobacco-related diseases compared with other tobacco products (modified risk pathway, Section 911(g)(1)).22 23 Alternatively, for the second pathway, a manufacturer can qualify by demonstrating that the product or its smoke is free of or contains reduced levels of harmful chemicals, but only if such claims do not mislead the public to believe the product poses less harm than other commercially available products (modified exposure pathway, Section 911(g)(2)).22 23 In 2014, Swedish Match North America filed the first MRTP application for 10 of their General snus products.24 The FDA did not grant the Swedish Match request for MRTP status.24 25 In 2016, Philip Morris International filed an MRTP application for its IQOS heated tobacco product.26 In January 2018, FDA’s Tobacco Product Scientific Advisory Committee voted that Philip Morris International’s application did not demonstrate reduced risks of disease. The FDA is also reviewing an MRTP application by Reynolds American for its Camel Snus.27 E-cigarettes are another tobacco product for which future modified-risk applications are likely.

The purpose of our study was to examine the impact of marketing claims about exposure and risk for potential MRTPs. We hypothesised that modified risk claims would lower perceptions of chemical quantity and health harm, and increase susceptibility to use an MRTP. Similarly, we hypothesised that modified exposure claims would lower perceptions of chemical quantity, lower perceived risk of health harm and increase use susceptibility. Of particular importance would be whether exposure claims lower perceived risk in the absence of explicit claims of lower risk, which would prevent a product from gaining an MRTP status under US law.

Methods

Participants

Participants were national samples of US adults and adolescents. The Carolina Survey Research Laboratory (CSRL) used sampling frames with coverage for 96% of US households, oversampling geographical areas, households and individuals to ensure adequate representation of smokers. CSRL recruited 4964 adults aged 18 years or older using both random digit dialling (of landlines and cell phones) and respondent-driven sampling approaches from August 2016 to May 2017. Separately, CSRL recruited 975 adolescents aged 13–17 years using random digit dial and list-assisted sampling frames from August 2016 to May 2017. The response rate was 39% for adults and 33% for adolescents. Adults provided consent verbally; adolescents’ parents or guardians provided consent verbally on behalf of their adolescents, who provided their assent verbally. The analytical sample comprised the 4797 adults and 969 adolescents who were correctly randomised and responded to all outcomes. Additional details about the survey methodology are available elsewhere.28 29

Procedures

We conducted two between-subjects factorial experiments. In Experiment 1, we randomised 2352 adults and 480 adolescents to receive one message that varied by (a) risk claim (less harmful than cigarettes, as harmful as cigarettes, no statement (control)) and (b) potential MRTP type (IQOS heated tobacco product, Apollo e-cigarette, Swedish snus), which we also refer to as product type. For example, a message about snus read, ‘I am going to describe a new type of moist tobacco called Swedish snus. It comes in a small pouch that goes under your lip. Suppose the FDA approves a label saying that Swedish snus is less harmful than cigarettes.’

In Experiment 2, we randomised 2445 adults and 489 adolescents to receive one message that varied by (a) exposure claim (20% less than cigarettes, 90% less than cigarettes, similar to cigarettes (control)) and (b) potential MRTP type (same as in Experiment 1). To increase the generalisability of the findings, the scenarios used one of three randomly selected chemicals (arsenic, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde). An example message about IQOS was, ‘I am going to describe a new type of cigarette called IQOS. It makes less smoke because it warms the tobacco without burning it. Suppose the FDA approves a label saying that IQOS exposes you to 90% less arsenic than cigarettes.’

Measures

We adapted survey items from previous studies, or for new items, cognitively tested them.30 The survey measured perceived chemical quantity with the following item, ‘Do you think that using [product] would expose you to…’ The 4-point response scale ranged from ‘almost no harmful chemicals’ (coded as 1) to ‘a lot of harmful chemicals’ (coded as 4). The survey assessed perceived risk of health harm using the following item, ‘If you used [product] regularly for the next 10 years, how likely do you think it is that you would eventually develop serious health problems?’ The 4-point response scale ranged from ‘not at all likely’ (1) to ‘extremely likely’ (4). This item includes the four components required to accurately gauge perceived risk: who is at risk, for what hazard, over what period of time, given a person’s behaviour.31 The survey measured susceptibility to use the potential MRTP, ‘If one of your best friends was to offer you [product], would you try it?’ The 4-point response scale ranged from ‘definitely not’ (1) to ‘definitely yes’ (4).

The survey also collected demographic data including education (for adolescents, maternal education). The survey assessed numeracy (ability to understand and use numeric information) using the item: ‘In general, which of these numbers shows the biggest risk of getting disease?’ Response options were: 1 in 10, 1 in 100 or 1 in 1000.32 We categorised adults as current smokers if they had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoke some days or every day.33 We categorised adolescents as current smokers if they had smoked at least 1 day in the past 30 days.34

Data analysis

We analysed the data using R (V.3.4.3).35 All statistical tests were two tailed and used a critical alpha of 0.05. In randomisation checks, only 25 associations of 80 models were significant (p<0.05) confirming that demographics, numeracy and smoking status were equally distributed across experimental conditions.

We conducted 2×3 between-subjects analyses of variance. Analyses combined categories for risk claim (less harmful than cigarettes vs as harmful as cigarettes or no statement) in Experiment 1 and exposure claim (similar to cigarettes vs 20% less or 90% less) in Experiment 2 because the combined categories showed the same pattern of results. We further examined statistically significant main effects of potential MRTPs with post hoc t-tests comparing IQOS and the e-cigarette to Swedish snus, using Bonferroni adjustments. Finally, we used linear regression models to examine whether perceived quantity and perceived risk mediated the relationship between independent variables and susceptibility to use MRTPs as a dependent variable. Analyses bootstrapped total, direct and mediated effects with 1000 iterations.

Results

The samples were 55% female, 67% white, 91% non-Hispanic and 70% non-smokers (table 1). Less than one-third had a high school diploma or equivalent or earned US$25 000 or less in annual income. Mean age for adults was 46 (SD=17) years and 45 (SD=17) years in Experiments 1 and 2, respectively. Mean age for adolescents was 15 (SD=1) years in both Experiments 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | |||

| Adults (n=2352) | Adolescents (n=480) | Adults (n=2445) | Adolescents (n=489) | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 13–17 | – | 100 | – | 100 |

| 18–25 | 15.2 | – | 17.5 | – |

| 26–34 | 14.5 | – | 16.0 | – |

| 35–44 | 16.7 | – | 16.2 | – |

| 45–54 | 18.2 | – | 17.3 | – |

| 55–64 | 21.6 | – | 19.4 | – |

| 65+ | 13.7 | – | 13.6 | – |

| Male | 45.0 | 50.0 | 45.5 | 49.0 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 67.1 | 79.2 | 67.2 | 82.4 |

| Black or African-American | 21.6 | 14.0 | 22.3 | 11.5 |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 3.9 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 1.0 |

| Asian or Pacific islander | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Other | 5.0 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

| Hispanic | 8.7 | 6.7 | 8.1 | 5.7 |

| Education | ||||

| <High school | 12.0 | 4.8 | 9.6 | 5.1 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 26.2 | 18.8 | 25.7 | 17.5 |

| Some college | 20.3 | 12.4 | 21.7 | 11.2 |

| Associate degree | 10.4 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 12.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 19.1 | 33.0 | 19.8 | 34.0 |

| Master’s degree | 9.3 | 15.8 | 9.1 | 15.4 |

| Professional or doctorate degree | 2.7 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| Low numeracy | 31.8 | 24.2 | 29.7 | 21.4 |

| Income per year | ||||

| US$0–US$24 999 | 31.0 | – | 29.8 | – |

| US$25 000–US$49 999 | 24.6 | – | 26.5 | – |

| US$50 000–US$74 999 | 17.9 | – | 18.5 | – |

| US$75 000–US$100 000 | 11.5 | – | 10.5 | – |

| >US$100 000 | 15.0 | – | 14.7 | – |

| Current smoker | 26.7 | 3.5 | 25.7 | 2.0 |

Among adults, missing data for income and education were 5% in Experiments 1 and 2. Among adolescents, missing data were less than 5% for age in Experiment 2 and 9% and 8% for mother’s education in Experiments 1 and 2, respectively. Missing data for other characteristics were minimal.

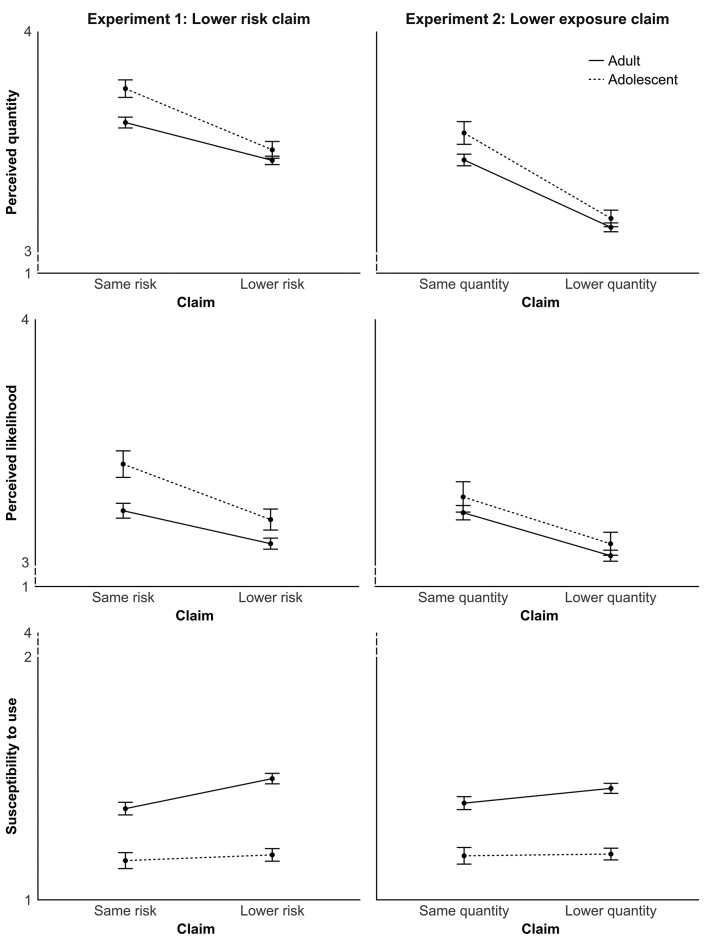

Experiment 1: lower risk claim

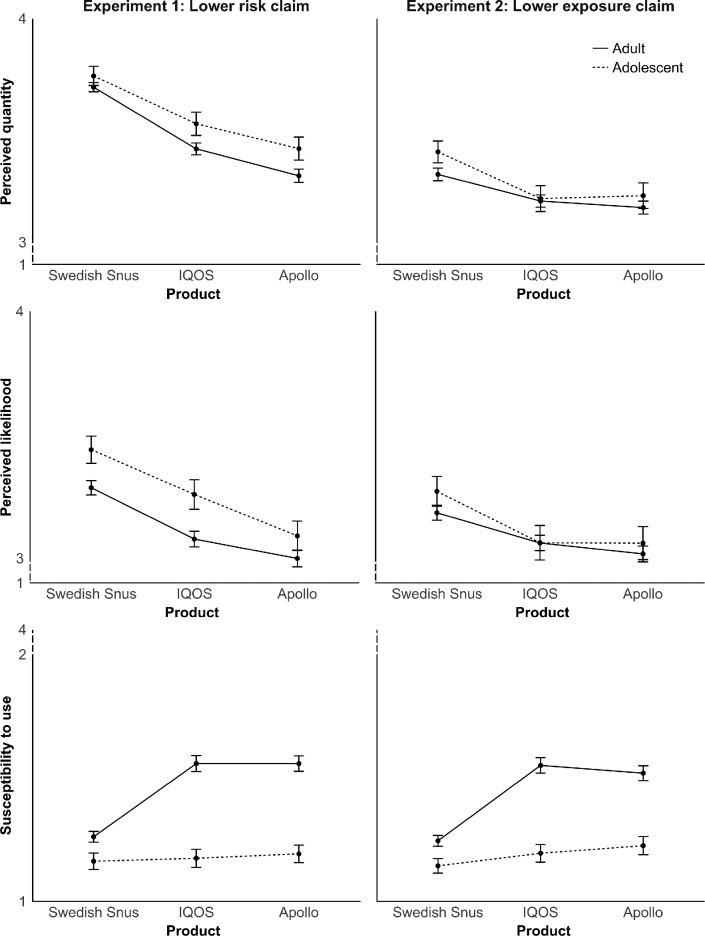

Perceived chemical quantity. Among adults, claims that an MRTP was less harmful than cigarettes led to lower perceived chemical quantity compared with claims that an MRTP was as harmful as cigarettes or when there was no statement (p<0.001) (table 2; figure 1). Perceived chemical quantity differed among the products (p<0.001); post hoc t-tests showed higher perceived chemical quantity for Swedish snus than for IQOS (p<0.001) and the e-cigarette (p<0.001) (figure 2). Adolescents showed the same pattern of results for the experimental manipulations.

Table 2.

Impact of lower risk and lower exposure claims

| df | Perceived quantity | Perceived risk | Use susceptibility | ||||

| Adults | Adolescents | Adults | Adolescents | Adults | Adolescents | ||

| F | F | F | F | F | F | ||

| Experiment 1 | |||||||

| Risk claim | 1 | 31.8** | 21.5** | 12.9** | 10.1* | 14.1** | 0.4 |

| Product | 2 | 50.0** | 10.6** | 19.7** | 8.6** | 31.4** | 0.5 |

| Risk claim×product | 2 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Experiment 2 | |||||||

| Exposure claim | 1 | 82.6** | 35.3** | 21.6** | 5.2* | 3.1 | 0.0 |

| Product | 2 | 8.4** | 5.5* | 8.9* | 2.9 | 30.6** | 1.3 |

| Exposure claim×product | 2 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

Experiment 1: n=2352 adults and 480 adolescents. Experiment 2: n=2445 adults and 489 adolescents. df=degrees of freedom.

*P<0.05, **P<0.001.

Figure 1.

Impact of lower risk claim (Experiment 1) and lower exposure claim (Experiment 2). Error bars show standard errors.

Figure 2.

Impact of potential modified risk tobacco product. Error bars show standard errors.

Perceived risk of health harm. Lower risk claims led to lower perceived risk of harm among adults (p<0.001). Perceived risk differed among the products (p<0.001); post hoc t-tests showed Swedish snus elicited higher perceived risk of harm than IQOS (p<0.001) and the e-cigarette (p<0.001). Adolescents again showed the same pattern of results as adults except that snus and IQOS did not differ.

Susceptibility to use potential MRTP. Lower risk claims elicited higher susceptibility to use the product among adults (p<0.001). Use susceptibility differed among the products (p<0.001); post hoc t-tests showed use susceptibility was lower for Swedish snus than for IQOS (p<0.001) and the e-cigarette (p<0.001). Among adolescents, risk claims and product type had no effect on use susceptibility. Interactions with smoking status were not statistically significant.

Mediation. Claims that an MRTP was less harmful than cigarettes elicited lower perceived chemical quantity, which in turn, was associated with greater use susceptibility among adults (mediated effect =0.07, p <0.001; table 3). Similarly, the claims elicited lower perceived risk, which was associated with greater use susceptibility (mediated effect=0.05, p<0.001). The two constructs also mediated the effect of product type on susceptibility among adults. Although risk claims and product type did not change adolescents’ susceptibility to use, analyses showed the same pattern of mediation as among adults. The correlation between the mediators, perceived chemical quantity and perceived risk, was r = 0.53 among adults and r=0.54 among adolescents (both p values < 0.001).

Table 3.

Path coefficients from mediation analysis for the effects of lower risk and lower exposure claims on susceptibility to use MRTPs

| Perceived quantity | Perceived risk | |||||||||

| a | b | c | c′ | Mediated effect | a | b | c | c′ | Mediated effect | |

| EXPERIMENT 1 | ||||||||||

| Adults (n=2352) | ||||||||||

| Risk claim | −0.17** | −0.41** | 0.12* | 0.05 | 0.07** | −0.14** | −0.34** | 0.12** | 0.08* | 0.5** |

| IQOS versus snus | −0.28** | −0.40** | 0.30** | 0.19** | 0.11** | −0.21** | −0.33** | 0.30** | 0.23** | 0.07** |

| E-cigarettes versus snus | −0.40** | −0.40** | 0.30** | 0.14** | 0.16** | −0.29** | −0.33** | 0.30** | 0.20** | 0.09** |

| Adolescents (n=480) | ||||||||||

| Risk claim | 0.28** | −0.17** | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.05** | −0.23* | −0.20** | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.05* |

| IQOS versus snus | −0.21* | −0.17** | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04** | −0.18* | −0.20** | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04* |

| E-cigarettes versus snus | −0.33** | −0.17** | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.06** | −0.35** | −0.20** | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.07** |

| EXPERIMENT 2 | ||||||||||

| Adults (n=2445) | ||||||||||

| Exposure claim | −0.31** | −0.29** | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.09** | −0.18** | −0.31** | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06** |

| IQOS versus snus | −0.12* | −0.27** | 0.31** | −0.27** | 0.03** | −0.12* | −0.30** | 0.31** | 0.27** | 0.04* |

| E-cigarettes versus snus | −0.15** | −0.27** | 0.27** | −0.23** | 0.04** | −0.17** | −0.30** | 0.27** | 0.22** | 0.05** |

| Adolescents (n=489) | ||||||||||

| Exposure claim | −0.39** | 0.19** | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.07** | −0.19* | −0.18** | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04* |

| IQOS versus snus | −0.21* | 0.17** | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04* | −0.21* | −0.18** | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04* |

| E-cigarettes versus snus | −0.20* | 0.17** | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03* | −0.21* | −0.18** | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04* |

a=path from independent variable to mediator. b=path from mediator to dependent variable. c=path from independent variable to dependent variable (total effect). cꞌ=c path adjusted for mediator (direct effect).

*P<0.05, **P<0.001.

MRTPs, modified risk tobacco products.

Experiment 2: lower exposure claim

Perceived chemical quantity. Among adults, claims that an MRTP exposed users to fewer chemicals led to lower perceived chemical quantity compared with the claim that an MRTP had chemical quantities similar to cigarettes (p<0.001) (table 2; figure 1). Perceived chemical quantity differed among the products (p<0.001); post hoc t-tests showed higher perceived chemical quantity for use of Swedish snus than IQOS (p=0.002) and the e-cigarette (p<0.001). Adolescents showed the same pattern of results as adults.

Perceived risk of health harm. Claims that an MRTP exposed users to less chemicals lowered adults’ perceived risk of health harm (p<0.001). Perceived risk differed among the products (p<0.001); post hoc t-tests showed perceived risk was higher for use of Swedish snus than IQOS (p=0.005) and e-cigarettes (p<0.001). Exposure claims had a similar effect on adolescents, but product type had no effect.

Susceptibility to use potential MRTP. Exposure claims did not change use susceptibility among adults or adolescents. Among adults, use susceptibility differed among the products (p<0.001); post hoc t-tests showed lower susceptibility to use Swedish snus than IQOS (p<0.001) or the e-cigarette (p<0.001). Among adolescents, use susceptibility did not vary among the products. Interactions with smoking status were not statistically significant.

Mediation. Although claims of lower exposure did not change adults’ susceptibility to use an MRTP, the claims led to lower perceived chemical quantity, which was associated with greater use susceptibility (mediated effect=0.09, p<0.001; table 3). Similarly, claims of lower exposure led to lower perceived risk, which was associated with greater use susceptibility (mediated effect=0.06, p<0.001). The two constructs also mediated the effect of product type on use susceptibility among adults. While risk claims and product type did not change adolescents’ susceptibility to use, lower exposure claims and product type showed similar mediation effects as among adults. The correlation between perceived chemical quantity and perceived risk was r=0.47 among adults and r=0.49 among adolescents (both p values<0.001).

Discussion

Tobacco product claims about reduced exposure to harmful chemicals and health risk had similar impact on the beliefs of four diverse samples of US adults and adolescents. A key finding was that claims of lower exposure led to lower perceived risk of harm from MRTP use, even in the absence of an explicit claim of reduced risk. This linkage makes it extremely unlikely that, absent actual evidence of reduced risk, reduced exposure claims can be allowed under the Tobacco Control Act without misleading consumers. Adults’ susceptibility to use MRTPs increased in response to lower risk claims but not in response to lower exposure claims whereas adolescents were not affected by either claim, suggesting some impact of claims on behaviour.

With respect to policy, a modified exposure claim would probably not satisfy US regulations for MRTP marketing.23 The intent of the law is to proactively ensure ‘that statements about MRTPs are complete, accurate and relate to the overall disease risk of the product’ because the ‘dangers of products sold or distributed as MRTPs that do not in fact reduce risk are so high.’36 National samples of adults and adolescents misinterpreted modified exposure claims as showing reduced risk. Accordingly, the modified exposure pathway (section 911(g)(2)) is not likely to be a viable legal mechanism to introduce and market MRTPs that reduce exposure without actually reducing risk. In contrast, in our studies the public interpreted modified risk claims as intended, which suggests a modified risk claim for a product that truly does reduce risk compared with other products would appear to satisfy US regulatory requirements with respect to public understanding.23 In addition, per the law, applications would need to back up the risk claim with clear evidence of reduction in health harms to support an issuance of a risk modification order under section 911(g)(1).23 Finally, our findings about use susceptibility suggest that, should the FDA issue a risk or exposure modification order, the agency should first require measures to minimise initiation among non-users and multiple tobacco product use among current users.

Several risk perception findings in our studies are likely to be generalisable beyond the context of MRTPs. First, the public infers that both risk and exposure are lower when they hear that either one is lower. Our participants perceived lower risk claims for MRTPs as indicating lower quantities of harmful chemicals and less health harm, consistent with previous studies.11 13 16 Our findings and previous studies also show claims of reduced quantities of chemicals are associated with lower perceived harm.12–14 17 Perceived risk and perceived chemical quantity were also highly correlated in our studies. Second, perceived risk is surprisingly responsive to claims about products and chemical amounts even in the absence of explicit reduced risk claims. Perceived risk is fairly insensitive to pictorial warnings and many other persuasion approaches.37 38 Yet, perceived risk changed in response to our experimental manipulations of exposure and risk claims, and MRTP type. It is reasonable for the public to think of lower exposure claims to be relevant to and influence the assessment of MRTP harm.39 Third, the public is quite susceptible to being misled about tobacco products. Exposure claims were misleading to our study participants. Tobacco companies have successfully misled the public on many topics for decades.12 13 16 Disclaimers are unlikely to remedy these misperceptions as evidenced by industry-sponsored studies26 and by external scientists.40

Exposure and risk beliefs mediated all pathways to susceptibility to use MRTPs in both experiments and age groups, which is broadly consistent with our hypotheses. However, only risk claims changed use susceptibility and only among adults. Nonetheless, the results raise some concerns about uptake of MRTPs given that susceptibility is a risk factor for tobacco use behaviour.41 This is concerning given the detrimental health effects of multiple (vs single) tobacco product use42 and those of any tobacco use compared with non-use.43 Among current tobacco users, MRTP marketing claims might encourage multiple tobacco product use. Previous studies show that users of non-cigarette tobacco products are less likely to quit44 and are more likely to progress to smoke cigarettes in addition to or instead of these alternative tobacco products.45 46 Among non-users, MRTP marketing claims might encourage initiation of tobacco use. This is particularly relevant to youth and their perceptions of potential MRTPs such as IQOS and e-cigarettes. Existing evidence on e-cigarettes shows that they appeal to youth because of their trendiness, youth-oriented flavours and social appeal.47 Literature on adolescents’ tobacco use shows that experimentation with non-cigarette tobacco products is a predictor of future cigarette smoking48 and multiple tobacco product use,49 and that adolescents who initiate tobacco use are more likely to continue using tobacco in their adulthood and experience its negative health effects over a longer period.50

Our studies’ strengths include national samples, inclusion of adults and adolescents, use of experimental designs, and replication of many of our findings across the samples. Limitations include the use of brief descriptions of the products, some of which may have been new to participants, and not examining actual product use. Using three tobacco products currently on the market increases the relevance of our results. Additional research is needed to replicate our findings with other candidate MRTPs, both existing and proposed.

Conclusion

Accuracy of claims and public comprehension of health risks associated with MRTPs are a requirement of US law.19 At long last, the Tobacco Control Act shifts the burden to tobacco manufacturers to demonstrate with scientific evidence that the issuance of an MRTP order under the Tobacco Control Act section 911 would be appropriate for the protection of the public health. Our national samples of adults and adolescents understood modified risk claims as intended. However, they misinterpreted modified exposure claims as communicating lower risk even when there was no explicit claim of lower risk, suggesting that this may not be a viable pathway under the law.

What this paper adds.

The US Tobacco Control Act allows marketing of tobacco products as causing less exposure to harmful chemicals only if this claim does not mislead the public into believing the product presents reduced risk of health harm.

Claims of lower exposure and lower risk acted similarly, with both leading to lower perceived quantity of harmful chemicals and lower perceived risk of health harm.

Absent concurrent evidence of reduced risk, claims of lower exposure are intrinsically misleading.

Claims of lower exposure do not satisfy US legal requirements for modified risk tobacco products.

Footnotes

Contributors: NTB, KMR, SAB and MJB designed the experiment. SAB conducted the analyses and SE-T led writing of the manuscript. All authors were involved in analysis and interpretation of data, as well as critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number P50CA180907 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The effort of SE-T was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (K99MD011755). This research was supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Health and Human Services, The National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Competing interests: None of the authors have received funding from tobacco product manufacturers. NTB and KMR have served as paid expert consultants in litigation against tobacco companies. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina approved study protocol and materials.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Gilpin EA, Emery S, White MM, et al. Does tobacco industry marketing of ’light' cigarettes give smokers a rationale for postponing quitting? Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4(Suppl 2):147–55. 10.1080/1462220021000032870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monitoring the future. Trends in 30-day prevalence of use of various drugs for grades 8, 10, and 12 combined. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/16data/16drtbl7.pdf (accessed 13 Nov 2017).

- 3. Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2005-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1233–40. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6444a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levy DT, Chaloupka F, Gitchell J. The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking rates: a tobacco control scorecard. J Public Health Manag Pract 2004;10:338–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stuber J, Galea S, Link BG. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:420–30. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stanford University Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. Can a cigarette with less toxin taste good? http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_web/images/tobacco_ads/filter_safety_myths/carcinogens/large/carcinogens_09.jpg (accessed 13 Feb 2018).

- 7. Stanford University Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. Reduced carcinogens. http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_web/images/tobacco_ads/filter_safety_myths/carcinogens/large/carcinogens_01.jpg (accessed 14 Feb 2018).

- 8. Klein EG, Berman M, Hemmerich N, et al. Online E-cigarette marketing claims: a systematic content and legal analysis. Tob Regul Sci 2016;2:252–62. 10.18001/TRS.2.3.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grana RA, Ling PM. "Smoking revolution": a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:395–403. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. Tobacco on the web: surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tob Control 2015;24:341–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Connor RJ, Lewis MJ, Adkison SE, et al. Perceptions of "natural" and "additive-free" cigarettes and intentions to purchase. Health Educ Behav 2017;44:222–6. 10.1177/1090198116653935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cummings KM, Hyland A, Bansal MA, et al. What do Marlboro Lights smokers know about low-tar cigarettes? Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(Suppl 3):323–32. 10.1080/14622200412331320725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shiffman S, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL, et al. Smokers' beliefs about "Light" and "Ultra Light" cigarettes. Tob Control 2001;10(Suppl 1):i17–i23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fix BV, Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, et al. Evaluation of modified risk claim advertising formats for Camel Snus. Health Educ J 2017;76:971–85. 10.1177/0017896917729723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pearson JL, Johnson AL, Johnson SE, et al. Adult interest in using a hypothetical modified risk tobacco product: findings from wave 1 of the population assessment of tobacco and health study (2013-14). Addiction 2018;113:113–24. 10.1111/add.13952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamilton WL, Norton G, Ouellette TK, et al. Smokers' responses to advertisements for regular and light cigarettes and potential reduced-exposure tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(Suppl 3):353–62. 10.1080/14622200412331320752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byron MJ, Jeong M, Abrams DB, et al. Public misperception that very low nicotine cigarettes are less carcinogenic. Tob Control 2018;27:712–4. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. U.S. Food and Drugs Administration. Food and Drug Administration. Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company, Inc. 8/27/15. 2015. https://www.fda.gov/ICECI/enforcementactions/warningletters/2015/ucm459778.htm (accessed 1 Feb 2018).

- 19. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Sec. 911, Pub. L. 111-31, 21 U.S.C. 387k (2009).

- 20. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Sec. 911(b)(1), Pub. L. 111-31, 21 U.S.C. 387k (2009).

- 21. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the FD&C Act) (21 U.S.C. 387k).

- 22. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Sec. 911(g), Pub. L. 111-31, 21 U S.C. 387k 2009.

- 23. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry, modified risk tobacco product applications, draft guidance. 2012. (accessed 1 Feb 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swedish Match North America, Inc. MRTP applications. https://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/labeling/marketingandadvertising/ucm533454.htm (accessed 5 Feb 2018).

- 25. Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes action on applications seeking to market modified risk tobacco products. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm533219.htm (accessed 5 Feb 2018).

- 26. Philip Morris Products S.A. Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) applications. https://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/labeling/marketingandadvertising/ucm546281.htm (accessed 5 Feb 2018).

- 27. U.S. Food and Drugs Administration. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) applications. https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/MarketingandAdvertising/ucm564399.htm (accessed 5 Feb 2018).

- 28. Boynton MH, Agans RP, Bowling JM, et al. Understanding how perceptions of tobacco constituents and the FDA relate to effective and credible tobacco risk messaging: a national phone survey of U.S. adults, 2014-2015. BMC Public Health 2016;16:516 10.1186/s12889-016-3151-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Agans RP, Bowling M, Boynton MH, et al. Using social networks to supplement RDD telephone surveys to oversample hard-to-reach populations: a new RDD+RDS approach. In Press.

- 30. Willis GB, Artino AR. What do our respondents think we’re asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:353–6. 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00154.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brewer NT, Weinstein ND, Cuite CL, et al. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Ann Behav Med 2004;27:125–30. 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lipkus IM, Samsa G, Rimer BK. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med Decis Making 2001;21:37–44. 10.1177/0272989X0102100105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Davis S, Malarcher A, Thorne S, et al. State-specific prevalence and trends in adult cigarette smoking--United States, 1998-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:381–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Team R Core. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Sec. 2(40), Pub. L. 111-31, 21 U.S.C. 387k (2009).

- 37. Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:905–12. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, et al. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control 2016;25:341–54. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwarz N. Judgment in a social context: biases, shortcomings, and the logic of conversation. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 1994;26:123–62. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Green KC, Armstrong JS. Evidence on the effects of mandatory disclaimers in advertising. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 2012;31:293–304. 10.1509/jppm.12.053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Unger JB, Johnson CA, Stoddard JL, et al. Identification of adolescents at risk for smoking initiation: validation of a measure of susceptibility. Addict Behav 1997;22:81–91. 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00107-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Choi K, Sabado M, El-Toukhy S, et al. Tobacco product use patterns, and nicotine and tobacco-specific nitrosamine exposure: NHANES 1999-2012. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1525–30. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation 2014;129:1972–86. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tomar SL. Is use of smokeless tobacco a risk factor for cigarette smoking? The U.S. experience. Nicotine Tob Res 2003;5:561–9. 10.1080/1462220031000118667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, et al. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:1018–23. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, et al. E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: adolescent and young adult perceptions of electronic nicotine delivery systems. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:2006–12. 10.1093/ntr/ntw095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watkins SL, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW. Association of noncigarette tobacco product use with future cigarette smoking among youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:181 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Soneji S, Sargent J, Tanski S. Multiple tobacco product use among US adolescents and young adults. Tob Control 2016;25:174–80. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. 3 Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]