Abstract

Rationale:

Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs) have risen as a useful tool in cardiovascular research, offering a wide gamut of translational and clinical applications. However, inefficiency of the currently available iPSC-EC differentiation protocol and underlying heterogeneity of derived iPSC-ECs remain as major limitations of iPSC-EC technology.

Objective:

Here we performed droplet-based single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) of the human iPSCs following iPSC-EC differentiation. Droplet-based scRNA-seq enables analysis of thousands of cells in parallel, allowing comprehensive analysis of transcriptional heterogeneity.

Methods and Results:

Bona fide iPSC-EC cluster was identified by scRNA-seq, which expressed high levels of endothelial-specific genes. iPSC-ECs, sorted by CD144 antibody-conjugated magnetic sorting, exhibited standard endothelial morphology and function including tube formation, response to inflammatory signals, and production of nitric oxide. Non-endothelial cell populations resulting from the differentiation protocol were identified, which included immature and atrial-like cardiomyocytes, hepatic-like cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Furthermore, scRNA-seq analysis of purified iPSC-ECs revealed transcriptional heterogeneity with four major subpopulations, marked by robust enrichment of CLDN5, APLNR, GJA5, and ESM1 genes respectively.

Conclusions:

Massively parallel, droplet-based scRNA-seq allowed meticulous analysis of thousands of human iPSCs subjected to iPSC-EC differentiation. Results showed inefficiency of the differentiation technique, which can be improved with further studies based on identification of molecular signatures that inhibit expansion of non-endothelial cell types. Subtypes of bona fide human iPSC-ECs were also identified, allowing us to sort for iPSC-ECs with specific biological function and identity.

Keywords: Single cell RNA-sequencing, induced pluripotent stem cells, endothelial cell differentiation, bioinformatics, Endothelium, Vascular Type, Nitric Oxide, Stem Cells

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States and in the world1. Endothelial dysfunction is implicated in pathogenesis of various CVDs including atherogenesis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and vascular inflammation2,3. To develop patient-specific CVD therapeutics tailored to their varying genetic and epigenetic backgrounds, the use of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cardiovascular cells has become essential4,5.

In particular, iPSC-derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs) has risen as a useful tool to study the precise pathobiology of patient-specific vascular diseases6. Human iPSC-ECs offer a wide spectrum of applications, from cell-based therapy to replace damaged or dysfunctional ECs in ischemic tissue7,8 to cell-free therapy by providing paracrine factors beneficial for tissue regeneration and repair9. Multiple reports have illustrated the therapeutic potential of human iPSC-ECs in preclinical animal models of retinopathy, myocardial infarction, and hindlimb ischemia10–12. iPSC-ECs also serve as an effective platform for vascular disease modeling and drug screening. Patient-specific iPSC-ECs have been used to successfully recapitulate in vitro the clinical phenotype of pulmonary arterial hypertension, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, diabetes mellitus, calcified aortic valvular disease, and cardiomyopathies13–15. In addition, iPSC-ECs have been used to generate organoids or bioengineered three-dimensional organ structures16,17.

However, there currently exists a number of limitations with the iPSC-EC technology that must be addressed6. First, the iPSC-EC differentiation protocol is not fully optimized and remains inefficient. The percentage of bona fide ECs obtained from the current differentiation protocols is low and variable. Heterogeneity of the iPSC-ECs has not been resolved, as the subpopulations of iPSC-ECs remain undetermined18. Reported methods to date for generating specific subtypes of iPSC-ECs are limited19.

To resolve these issues, we performed large-scale single-cell RNA-seq across the iPSC-EC differentiation to identify heterogeneous populations of iPSC-ECs. Droplet-based single-cell RNA-seq is a powerful, state-of-the-art tool in analyzing transcriptome of thousands of cells in parallel20,21. In contrast to the plate-based or automated microfluidic-based scRNA-seq techniques that are limited to analysis of tens to hundreds of cells, microdroplet-based scRNA-seq allows parallel analysis of thousands of cells per experiment, enabling comprehensive characterization of heterogeneous cell populations22.

In this study, we identified bona fide iPSC-EC cluster during the differentiation process, which exclusively expressed endothelial-specific genes. We characterized various non-endothelial cell types of mesodermal lineage generated during differentiation. Lastly, we identified four major subpopulations of iPSC-ECs marked by robust enrichment of CLDN5, APLNR, GJA5, and ESM1 genes respectively. Enabled by massively parallel scRNA-seq analysis, our findings uncover the inefficiency of iPSC-EC differentiation and heterogeneity of human iPSC-ECs.

METHODS

All data have been made publicly available at NCBI GEO Datasets and can be accessed at GSE116555, or from the corresponding author upon request.

Detailed Methods section is available in the Supplemental Material.

RESULTS

Differentiation of human iPSCs to bona fide endothelial cells.

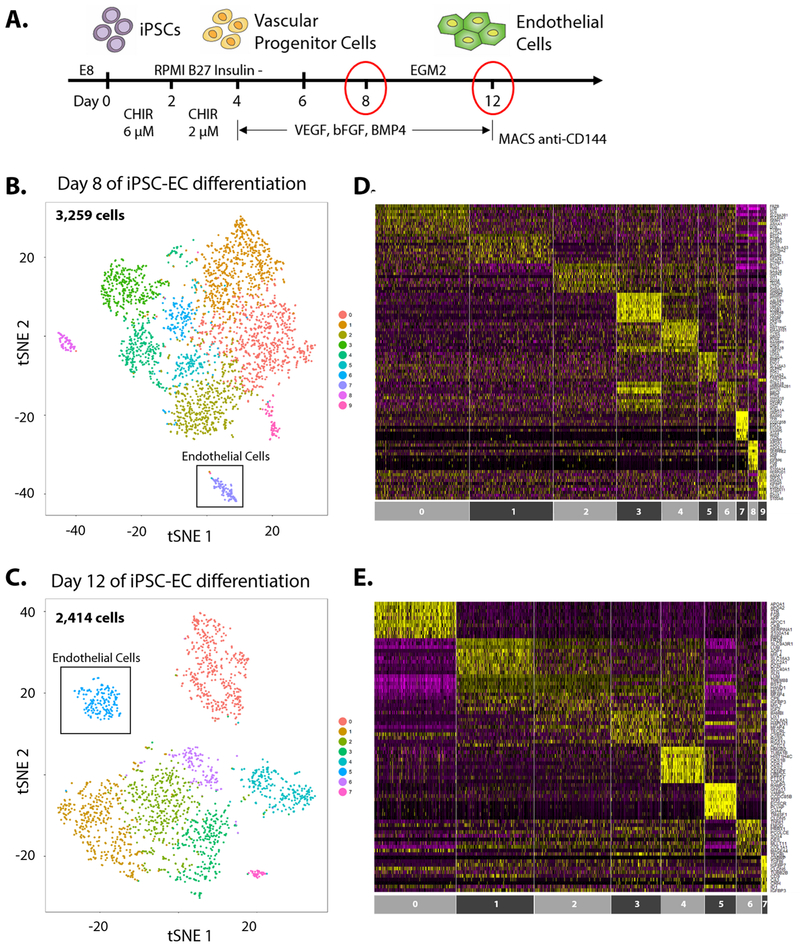

Human iPSCs were differentiated using a monolayer-based, serum-free protocol as previously described15,23. In brief, the iPSCs were treated with 6 μM CHIR from day 0 to 2 and 2 μM CHIR from day 2 to 4 to generate mesoderm. From day 4 to 12 of differentiation, cells were treated with VEGF, bFGF, and BMP4 in EGM2 endothelial growth media to promote specification to endothelial cells. On day 12 of differentiation, bona fide endothelial cells were positively selected by magnetic-activated cell sorting using bead-conjugated CD144 antibody (Fig. 1A). The sorted iPSC-ECs express endothelial-specific transcription regulator ETS-related gene (ERG) and endothelial-specific cadherin protein VE-cadherin (also known as CD144 or CDH5) (Online Fig. I-A, B). The iPSC-ECs exhibited cobblestone-like morphology, formed tube-like networks on Matrigel substrate and migrated in wound scratch assay, demonstrating endothelial identity and function (Online Fig. I-C). The iPSC-ECs also generated nitric oxide (NO) (Online Fig. I-D) and took up acetylated low-density lipoprotein (AcLDL) (Online Fig. I-E). When treated with ATP or TNFα, iPSC-ECs induced expression of cell surface molecules ICAM1, VCAM1, and E-Selectin, indicating iPSC-ECs are activated in response to danger-associated molecular pattern (e.g., ATP) or to pro-inflammatory cytokine (e.g., TNFα) (Online Fig. I-F).

Figure 1. Monolayer-based differentiation of human iPSCs to endothelial cells.

(A) Schematic representation of endothelial cell differentiation from human iPSCs. At day 12 of differentiation, bona fide iPSC-ECs are purified by MACS sorting with bead-conjugated CD144 antibody and cultured for up to five passages. t-SNE plots of scRNA-seq at (B) day 8 and (C) day 12 of human iPSCs subjected to EC differentiation. Heatmaps of enriched gene expression for each cluster of cells in (D) day 8 and (E) day 12 of differentiation.

Large-scale single-cell RNA-sequencing of day 8 and day 12 of iPSC-EC differentiation.

Large-scale single cell RNA-seq (10X Genomics) were performed on differentiating iPSCs at day 8 and day 12 of EC differentiation. Seurat R package was used to log-normalize and analyze data24. Cells with a clear outlier number of genes were perceived as potential multiplets and excluded from subsequent analyses - cells with 3500+ genes in “day 8” sample and 4000+ genes in “day 12” sample were therefore excluded from downstream analysis (Online Fig. II). Likewise, cells with mitochondrial gene percentage of 0.05% or above were excluded in both samples (Online Fig. II). A total of 3,259 cells and 2,414 cells were captured in “day 8” and “day 12” samples respectively (Online Table I). Statistically significant principal components were determined (Online Fig. III) and non-linear dimensional reduction (t-SNE) to two t-SNE dimensions was performed, resulting in 10 clusters of cells for “day 8” cells and 8 clusters for “day 12” cells (Fig. 1B, C). Each cluster is defined by a unique set of differentially expressed genes20. Heatmaps show highly differentially expressed genes for each cluster of cells (Fig. 1D, E). Individual clusters possess variable number of cells, ranging from 71 to 726 cells per cluster (Fig. 2A).

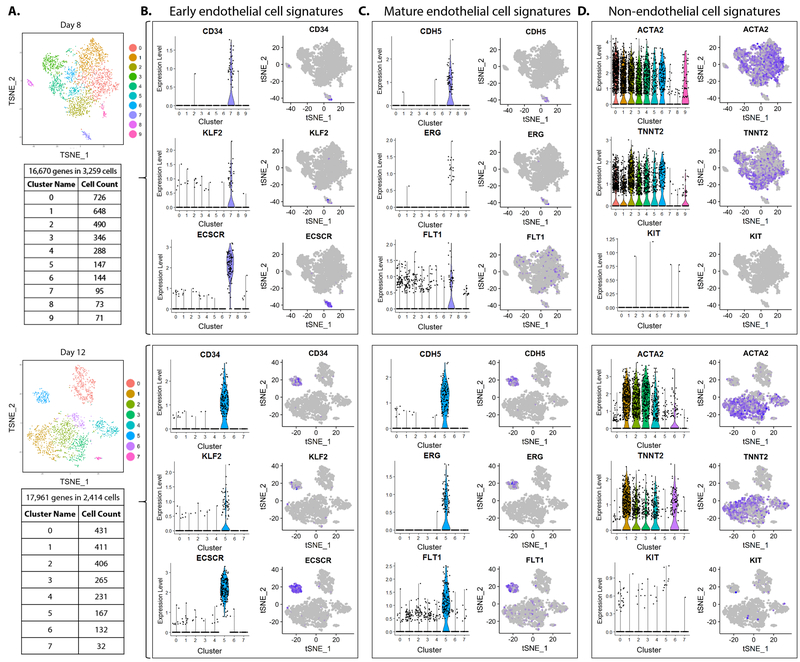

Figure 2. Identification of bona fide iPSC-EC cluster.

(A) Number of cells counted in each of ten clusters of day 8 (top) and of eight clusters of day 12 (bottom) of iPSC-EC differentiation. (B) Expression of early endothelial cell signatures (CD34, KLF2, ECSCR), (C) mature endothelial cell signatures (CDH5, ERG, FLT1), and (D) non-endothelial cell signatures (mesenchymal marker ACTA2, cardiac marker TNNT2, hematopoietic marker KIT) visualized by ViolinPlots (left) and FeaturePlots (right).

Identification of iPSC-derived endothelial cells.

To identify the cell cluster(s) representative of bona fide iPSC-ECs, expression of known markers of endothelial cells were visualized by ViolinPlot and FeaturePlot functions of Seurat20. Early endothelial cell markers (e.g., CD34, KLF2, ECSCR) were expressed exclusively in cluster 7 of “day 8” sample and in cluster 5 of “day 12” sample (Fig. 2B). Mature endothelial cell markers (e.g., CDH5, ERG, FLT1) were similarly expressed in the identical clusters in each of the two samples respectively (Fig. 2C). The level of expression and number of cells expressing both early and mature endothelial markers were markedly increased in the iPSC-EC cluster on day 12 than in day 8. Expression of non-endothelial cell markers, such as ACTA2 (mesenchymal), TNNT2 (cardiac), and KIT (hematopoietic) were absent in the iPSC-EC clusters (Fig. 2D), indicating these clusters were exclusively endothelial and transcriptionally distinct from other cell types.

Canonical correlation analysis of day 8 and day 12 iPSC-EC differentiation.

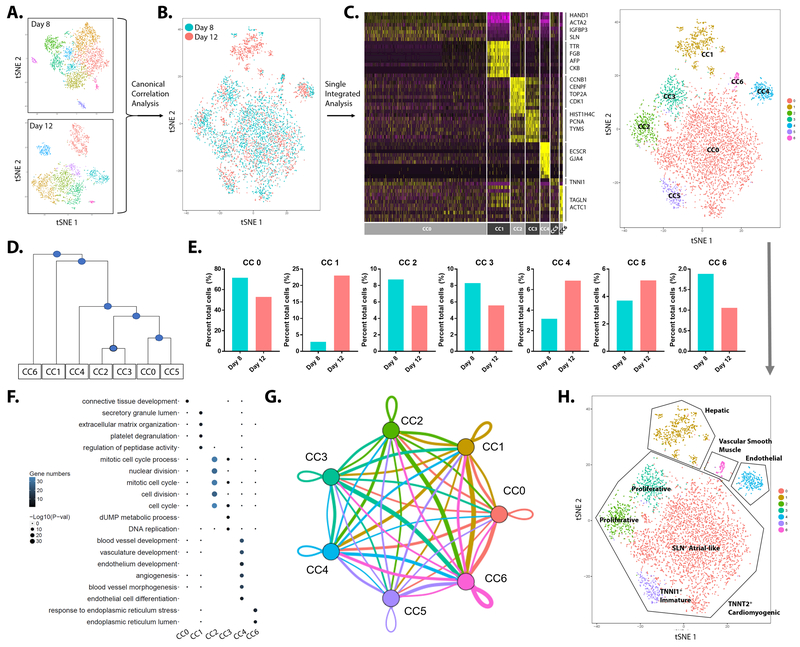

In order to track differentiating cells from day 8 to 12, canonical correlation analysis (CCA) of scRNA-seq data of the two differentiation days was performed using the Seurat package. CCA combined the two datasets and clustered cells with similar transcriptomic profiles (Fig. 3A, B). Single integrated analysis of the combined datasets then defined seven individual clusters (termed CC0 to CC6) from cells pooled from both datasets (Fig. 3C; Online Table II). Hierarchical analysis showed greatest transcriptomic similarity among the four clusters CC0, CC5, CC2, and CC3. Cluster CC4 showed some similarity to this group of clusters, while clusters CC6 and CC1 were more distinctive (Fig. 3D). To elucidate the differentiation process of cells in each cluster, the number of cells per cluster at the two days of differentiation was counted (Fig. 3E). Cell numbers in clusters CC0, CC2, CC3, and CC6 decreased from day 8 to 12, whereas cell numbers in clusters CC1, CC4, and CC5 increased from day 8 to 12. Greatest increase in cell number occurred in CC1 (~10-fold), followed by CC4 (~2.5-fold). To identify the biological function and cell identity of each cluster, pathway enrichment analysis was performed to reveal statistically significant gene ontologies for each cluster (Fig. 3F). Based on this information, CC4 was identified as the bona fide iPSC-EC cluster that expressed genes known to regulate blood vessel development, vasculature development, endothelium development, and angiogenesis (Online Fig. IV-A, B). Furthermore, cellular interaction and molecular crosstalk, such as ligand-to-receptor interactions among the clusters were determined at the transcriptomic level (Fig, 3G; Online Fig. IV-C, D; Online Fig. V). Using these approaches, cell identities for all clusters were determined (Fig. 3H). Clusters CC0, CC2, CC3, and CC5 were TNNT2-high cardiomyogenic cells. Cluster CC0 represented Sarcolipin (SLN)- and TMEM88-high atrial-like cardiomyocytes, which also displayed expression of mesenchymal genes such as LUM, ACTA2, and IGFBP3 (Online Table II). CC5 represented Troponin I1 (TNNI1)-high cardiomyocytes with immature sarcomeric formation25. CC2 and CC3 cells were identified as proliferative cardiomyocytes expressing genes that regulate cell cycle and cell division, such as TOP2A, CDK1, PCNA, and HIST1H4C (Fig. 3C). Cluster CC1 was found to be hepatocyte-like cells, expressing Transthyretin (TTR) and α-Fetoprotein (AFP) (Fig. 3C, H). Cluster CC6 was Transgelin (TAGLN)-expressing vascular smooth muscle-like cells (Fig. 3C, H). Thus, the current iPSC-EC differentiation protocol generates a pure population of bona fide iPSC-ECs but also large numbers of cardiomyocytes as well as other cell types of mesodermal lineage by day 12 of differentiation.

Figure 3. Canonical correlation analysis of day 8 and day 12 iPSC-EC differentiation.

(A) Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) of day 8 and day 12 samples combines the two datasets. (B) t-SNE plot of CCA shows cells from two independent samples correlating based on transcriptional similarity. (C) Heatmap (left) and t-SNE plot (right) of single integrated analysis reveal seven canonically-correlated (CC) clusters (CC0-CC6). (D) Hierarchical analysis of seven CC clusters. (E) Percentage of cell number is determined for each CC cluster. (F) Pathway enrichment analysis shows statistically significant gene ontologies. (G) Intercellular communication analysis amongst CC clusters. Line color indicates ligands broadcast by the cell population of the same color (labeled). Lines connect to cell populations where cognate receptors are expressed. Line thickness is proportional to the number of ligands where cognate receptors are present in the recipient cell population. Loops indicate autocrine circuits. Map quantifies potential communication but does not account for anatomic position or boundaries of cell populations. (H) Biological function and identity of each CC cluster are identified and are labeled accordingly.

Unique molecular signatures define heterogeneous populations of iPSC-ECs.

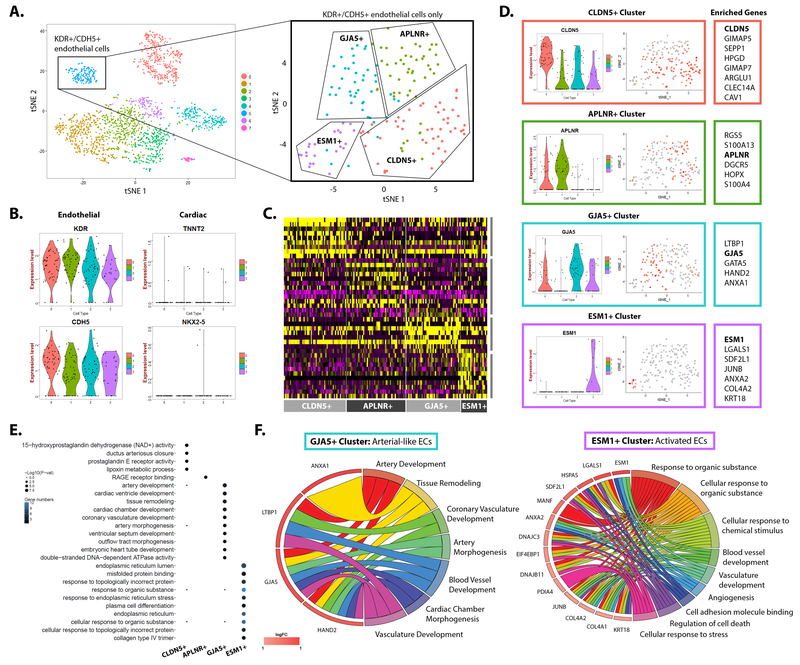

To elucidate the heterogeneity of differentiated iPSC-ECs, the iPSC-EC cluster (cluster 5) at day 12 was isolated as an independent Seurat object and sub-clustering was performed (Fig. 4A). Four iPSC-EC sub-clusters were generated, with all clusters showing high level of expression of pan-endothelial markers KDR and CDH5 and no expression of cardiac genes TNNT2 or NKX2-5 (Fig. 4B). Each sub-cluster is defined by a unique set of differentially expressed genes (Fig. 4C). For example, Claudin-5 (CLDN5) is expressed throughout the majority of iPSC-ECs but is particularly enriched in one of the four sub-clusters (Fig. 4D). Similarly, expressions of Apelin Receptor (APLNR), Gap Junction Protein Alpha 5 (GJA5), and Endocan (ESM1) were enriched in each of the sub-clusters and hence these four membrane protein coding genes were used to distinguish each sub-cluster (Fig. 4D). Pathway enrichment analysis of the four iPSC-EC sub-clusters revealed their biological function (Fig. 4E). CLDN5+ cluster represented metabolically active iPSC-ECs with expression of genes related to mitochondrial integrity and metabolic function such as GIMAP5, HPGD, and CAV1 (Fig. 4D, E). APLNR+ cluster represented inflammation-responsive iPSC-ECs with expression of genes related to innate immune response such as RAGE receptor binding (Fig. 4D, E). GJA5+ iPSC-ECs showed robust expression of four genes related to arterial EC development in ANXA1, LTBP1, GJA5, and HAND2, indicating that GJA5 can be used as a robust marker for human arterial iPSC-ECs26–28 (Fig. 4D-F). ESM1+ iPSC-ECs showed gene ontologies for angiogenesis, regulation of cell death, and cellular response to chemical stimulus and stress, representing activated iPSC-ECs (Fig. 4F). ESM1 is thus a robust marker for human iPSC-ECs in the activated state, which can be used to distinguish iPSC-ECs under inflammatory or angiogenic conditions from the senescent state. The expression of enriched genes in the four subpopulations were confirmed in bulk RNA-seq data of human pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells from independent studies29,30 (Online Fig. VI).

Figure 4. Novel molecular signatures that define heterogeneous populations of human iPSC-ECs.

(A) Bona fide iPSC-EC cluster on the final day of differentiation is further analyzed by sub-clustering. The iPSC-ECs are divided into four distinct sub-clusters, marked by expression of CLDN5, APLNR, GJA5, and ESM1. (B) All iPSC-EC sub-clusters show high expression of endothelial markers KDR and CDH5 while no expression of cardiac markers TNNT2 or NKX2–5. (C) Heatmap shows enriched genes of four iPSC-EC sub-clusters. (D) Representative ViolinPlots and FeaturePlots of enriched genes in sub-clusters. (E) Pathway enrichment analysis reveals statistically significant gene ontologies for each iPSC-EC sub-cluster. (F) GJA5+ cluster represents arterial-like endothelial cells (left). ESM1+ cluster represents activated endothelial cells with enriched expression of genes related to angiogenesis, regulation of cell death, cell adhesion molecule binding, and response to stress and chemical stimulus.

Arterial and venous classification of iPSC-ECs.

Expressions of traditionally-known markers for arterial, venous, and lymphatic endothelial specification19 were investigated. Arterial endothelial genes of NRP1, EFNB2, and NOTCH1 were highly expressed in the majority of iPSC-EC clusters, whereas venous endothelial genes of EPHB4, NR2F2, and NOTCH4 were modestly expressed in iPSC-EC clusters (Online Fig. VII-A). In particular, expression of venous genes was nearly absent in the GJA5+ cluster, which supports our identification of the cluster as arterial-specific iPSC-ECs (Fig. 4F). Very few iPSC-ECs expressed PROX1 and PDPN, markers of lymphatic endothelial cells (Online Fig. VII-A). The number of iPSC-ECs of each subtype was counted and plotted as Venn diagram (Online Fig. VII-B). Arterial iPSC-ECs were greatest in numbers and its population increased by 4-fold from day 8 to day 12. Expression of iPSC-EC genes were also confirmed in human aortic endothelial cells and HUVECs (Online Fig. VI-B).

DISCUSSION

Here we employ a monolayer-based, chemically-defined differentiation protocol to generate bona fide iPSC-ECs. Resulting iPSC-ECs exhibit cobblestone-like morphology and endothelial function, indicating the patient-specific ECs can be used for vascular disease modeling and drug screening6. However, the iPSC-EC differentiation protocol suffers from a number of limitations, most notably in the low yield and significant heterogeneity of the derived bona fide iPSC-ECs. To address these problems, we performed droplet-based scRNA-seq of human iPSCs subjected to EC differentiation and analyzed thousands of cells per sample in parallel.

Our scRNA-seq data reveal the current differentiation protocol generates cells of several mesodermal lineages. A large number of differentiated cells were cardiomyocyte-like cells, expressing TNNT2 and NKX2-5. These cells were divided into three transcriptionally distinct groups: a proliferative cardiomyocyte cluster, a functionally immature cardiomyocyte cluster, and atrial-like cardiomyocyte cluster. Following mesodermal formation by GSK-3 inhibition, the continuous exogenous addition of VEGF in the protocol is intended for differentiation of vascular progenitor cells and ECs. However, VEGF has also been shown to promote cardiomyocyte differentiation from pluripotent stem cells31–33. Previous studies have shown VEGF activates ERK and JNK signaling pathways in cardiac progenitor cells and cardiomyocytes that express high levels of the VEGF receptors FLT1 and KDR31,34. During embryonic stem cell differentiation, VEGF was shown to increase the levels of cardiac-specific proteins TNNI1 and NKX2-5, which were highly expressed in the cardiomyocyte-like cells derived from the human iPSC-EC differentiation31.

A low percentage of cells from the differentiation protocol were hepatic-like cells. The hepatic-like cells increased by 10-fold from day 8 to 12 of differentiation, indicating a rapid expansion during the late phase of iPSC-EC differentiation. VEGF has been previously shown to promote hepatic maturation during the final stage of hepatocyte-like cells from iPSCs35. Another low percentage of non-endothelial cells were vascular smooth muscle cells, whose number modestly decreased from day 8 to 12 of differentiation.

Transcriptomic analysis of bona fide iPSC-ECs on the final day of differentiation identified four distinct populations of iPSC-ECs, noted by enriched expressions of CLDN5, APLNR, GJA5, and ESM1 respectively. Regulation of various signaling pathways controls biological and physiological functionality of endothelial cells36,37. Likewise, the identified iPSC-EC subpopulations displayed enriched expression of genes that together indicate specialized biological functions as metabolically active (CLDN5+), immune-responsive (APLNR+), arterial (GJA5+), and activated (ESM1+) ECs.

In conclusion, we performed large-scale scRNA-seq to better understand the limitations of currently existing iPSC-EC differentiation protocol and to resolve the transcriptional heterogeneity of the resulting iPSC-ECs. Co-presence of various endothelial subtypes in iPSC-ECs currently confines the use of the cells to uncover mechanisms of specific vascular disease conditions such as arterial hypertension, aortic diseases, vasculopathies, and lymphedemas. Based on the findings from this study, future efforts will aim to enable derivation of iPSC-ECs of specific origin and function, which will be necessary for effective disease modeling and for elucidation of molecular mechanisms of vascular diseases. Improved versions of patient-specific iPSC-ECs can also be used as a source of autologous cells for cardiovascular regenerative medicine, where iPSC-ECs of fitting origin and function can replace the damaged ECs in ischemic conditions.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Endothelial cells derived from patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC-ECs) provide a platform for elucidating molecular and cellular mechanisms of vascular diseases.

Generation of iPSC-ECs with currently available methodologies remains inefficient, yielding a low percentage of bona fide iPSC-ECs.

Heterogeneity of iPSC-ECs is high, whose identity and biological functions remain undetermined.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Using large-scale single-cell RNA-sequencing, we provide single-cell transcriptome of differentiating iPSC-ECs at two time-points of differentiation.

Four subpopulations of iPSC-ECs are identified, marked by robust expression of CLDN5, APLNR, GJA5, and ESM1 respectively.

Currently generated iPSC-ECs are predominantly arterial-like ECs, with low number of venous and lymphatic ECs.

Patient-specific iPSCs allow mass generation of endothelial cells to recapitulate in vitro the clinical phenotype of the patient’s vascular dysfunction. iPSCs serve as an effective platform to investigate patient-specific disease mechanisms and to screen and test drugs in non-invasive, high-throughput manner. While iPSC-derived endothelial cells (iPSC-ECs) present a wide gamut of preclinical and clinical applications, there remains a number of limitations with the technology. Most notably, the efficiency of differentiation protocol is suboptimal and the large heterogeneity of iPSC-ECs remains undetermined. In this study, we use large-scale single-cell RNA-sequencing of iPSCs during EC differentiation to address these issues. From the single-cell transcriptome analysis of bona fide iPSC-ECs, we uncovered identities of iPSC-EC subpopulations and their biological function. We define enriched genes and molecular signaling pathways that govern the subpopulations of iPSC-ECs, which will be used as cues to generate iPSC-ECs of specific origin and function in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dhananjay Wagh and John Coller of Stanford Functional Genomics Facility for assistance with single-cell RNA-sequencing. We thank Soah Lee for assistance with graphical design.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 EB009035 (D.T.P.), F32 HL134221 (J-W.R.), K01 HL135455 and American Heart Association grant 13SDG17340025 (N.S.), R01 HL134817, R01 HL128170, R01 HL123968, R33 HL120757 (T.Q.), R01 HL113006, R01 HL130020, R01 HL128170, R01 HL132875, and Burroughs Wellcome Foundation 1015009 (J.C.W.).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- EC

Endothelial cell

- scRNA-seq

Single cell RNA-sequencing

- CCA

Canonical correlation analysis

- CLDN5

Claudin-5

- APLNR

Apelin Receptor

- GJA5

Gap Junction alpha-5

- ESM1

Endothelial Cell Specific Molecule 1

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

In June 2018, the average time from submission to first decision for all original research papers submitted to Circulation Research was 13.26 days.

This manuscript was sent to Buddhadeb Dawn, Consulting Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:840–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gimbrone MA, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:620–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen IY, Matsa E, Wu JC. Induced pluripotent stem cells: at the heart of cardiovascular precision medicine. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13:333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida Y, Yamanaka S. Induced pluripotent stem cells 10 years later: For cardiac applications. Circ Res. 2017;120:1958–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Y, Gil C-H, Yoder MC. Differentiation, evaluation, and application of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:2014–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou L, Coller J, Natu V, Hastie TJ, Huang NF. Combinatorial extracellular matrix microenvironments promote survival and phenotype of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells in hypoxia. Acta Biomater. 2016;44:188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S-J, Sohn Y-D, Andukuri A, Kim S, Byun J, Han JW, Park I-H, Jun H-W, Yoon Y-S. Enhanced therapeutic and long-term dynamic vascularization effects of human pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells encapsulated in a nanomatrix gel. Circulation. 2017;136:1939–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung J-H, Fu X, Yang PC. Exosomes generated from iPSC-derivatives: new direction for stem cell therapy in human heart diseases. Circ Res. 2017;120:407–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rufaihah AJ, Huang NF, Jamé S, Lee JC, Nguyen HN, Byers B, De A, Okogbaa J, Rollins M, Reijo-Pera R, Gambhir SS, Cooke JP. Endothelial cells derived from human iPSCs increase capillary density and improve perfusion in a mouse model of peripheral arterial disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:e72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo CH, Na H-J, Lee D-S, Heo SC, An Y, Cha J, Choi C, Kim JH, Park J-C, Cho YS. Endothelial progenitor cells from human dental pulp-derived iPS cells as a therapeutic target for ischemic vascular diseases. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8149–8160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park TS, Bhutto I, Zimmerlin L, Huo JS, Nagaria P, Miller D, Rufaihah AJ, Talbot C, Aguilar J, Grebe R, Merges C, Reijo-Pera R, Feldman RA, Rassool F, Cooke J, Lutty G, Zambidis ET. Vascular progenitors from cord blood-derived induced pluripotent stem cells possess augmented capacity for regenerating ischemic retinal vasculature. Circulation. 2014;129:359–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theodoris CV, Li M, White MP, Liu L, He D, Pollard KS, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Human disease modeling reveals integrated transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of NOTCH1 haploinsufficiency. Cell. 2015;160:1072–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barruet E, Morales BM, Lwin W, White MP, Theodoris CV, Kim H, Urrutia A, Wong SA, Srivastava D, Hsiao EC. The ACVR1 R206H mutation found in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva increases human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cell formation and collagen production through BMP-mediated SMAD1/5/8 signaling. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu M, Shao N-Y, Sa S, Li D, Termglinchan V, Ameen M, Karakikes I, Sosa G, Grubert F, Lee J, Cao A, Taylor S, Ma Y, Zhao Z, Chappell J, Hamid R, Austin ED, Gold JD, Wu JC, Snyder MP, Rabinovitch M. Patient-specific iPSC-derived endothelial cells uncover pathways that protect against pulmonary hypertension in BMPR2 mutation carriers. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:490–504. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama KH, Hong G, Lee JC, Patel J, Edwards B, Zaitseva TS, Paukshto MV, Dai H, Cooke JP, Woo YJ, Huang NF. Aligned-braided nanofibrillar scaffold with endothelial cells enhances arteriogenesis. ACS Nano. 2015;9:6900–6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JJ, Hou L, Huang NF. Vascularization of three-dimensional engineered tissues for regenerative medicine applications. Acta Biomater. 2016;41:17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rufaihah AJ, Huang NF, Kim J, Herold J, Volz KS, Park TS, Lee JC, Zambidis ET, Reijo-Pera R, Cooke JP. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells exhibit functional heterogeneity. Am J Transl Res. 2013;5:21–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Chu L-F, Hou Z, Schwartz MP, Hacker T, Vickerman V, Swanson S, Leng N, Nguyen BK, Elwell A, Bolin J, Brown ME, Stewart R, Burlingham WJ, Murphy WL, Thomson JA. Functional characterization of human pluripotent stem cell-derived arterial endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E6072–E6078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, Trombetta JJ, Weitz DA, Sanes JR, Shalek AK, Regev A, McCarroll SA. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng GXY, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, Ziraldo SB, Wheeler TD, McDermott GP, Zhu J, Gregory MT, Shuga J, Montesclaros L, Underwood JG, Masquelier DA, Nishimura SY, Schnall-Levin M, Wyatt PW, Hindson CM, Bharadwaj R, Wong A, Ness KD, Beppu LW, Deeg HJ, McFarland C, Loeb KR, Valente WJ, Ericson NG, Stevens EA, Radich JP, Mikkelsen TS, Hindson BJ, Bielas JH. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papalexi E, Satija R. Single-cell RNA sequencing to explore immune cell heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayed N, Wong WT, Ospino F, Meng S, Lee J, Jha A, Dexheimer P, Aronow BJ, Cooke JP. Transdifferentiation of human fibroblasts to endothelial cells: role of innate immunity. Circulation. 2015;131:300–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:495–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bedada FB, Chan SS-K, Metzger SK, Zhang L, Zhang J, Garry DJ, Kamp TJ, Kyba M, Metzger JM. Acquisition of a quantitative, stoichiometrically conserved ratiometric marker of maturation status in stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:594–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh HI, Lai YJ, Chang HM, Ko YS, Severs NJ, Tsai CH. Multiple connexin expression in regenerating arterial endothelial gap junctions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1753–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buschmann I, Pries A, Styp-Rekowska B, Hillmeister P, Loufrani L, Henrion D, Shi Y, Duelsner A, Hoefer I, Gatzke N, Wang H, Lehmann K, Ulm L, Ritter Z, Hauff P, Hlushchuk R, Djonov V, van Veen T, le Noble F. Pulsatile shear and Gja5 modulate arterial identity and remodeling events during flow-driven arteriogenesis. Dev Camb Engl. 2010;137:2187–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gkatzis K, Thalgott J, Dos-Santos-Luis D, Martin S, Lamandé N, Carette MF, Disch F, Snijder RJ, Westermann CJ, Mager JJ, Oh SP, Miquerol L, Arthur HM, Mummery CL, Lebrin F. Interaction Between ALK1 Signaling and Connexin40 in the Development of Arteriovenous Malformations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:707–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohta R, Niwa A, Taniguchi Y, Suzuki NM, Toga J, Yagi E, Saiki N, Nishinaka-Arai Y, Okada C, Watanabe A, Nakahata T, Sekiguchi K, Saito MK. Laminin-guided highly efficient endothelial commitment from human pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao M-T, Chen H, Liu Q, Shao N-Y, Sayed N, Wo H-T, Zhang JZ, Ong S-G, Liu C, Kim Y, Yang H, Chour T, Ma H, Gutierrez NM, Karakikes I, Mitalipov S, Snyder MP, Wu JC. Molecular and functional resemblance of differentiated cells derived from isogenic human iPSCs and SCNT-derived ESCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E11111–E11120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Amende I, Hampton TG, Yang Y, Ke Q, Min J-Y, Xiao Y-F, Morgan JP. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1653–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, Henckaerts E, Bonham K, Abbott GW, Linden RM, Field LJ, Keller GM. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JH, Protze SI, Laksman Z, Backx PH, Keller GM. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes develop from distinct mesoderm populations. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:179–194. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pimentel RC, Yamada KA, Kléber AG, Saffitz JE. Autocrine regulation of myocyte Cx43 expression by VEGF. Circ Res. 2002;90:671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han S, Bourdon A, Hamou W, Dziedzic N, Goldman O, Gouon-Evans V. Generation of functional hepatic cells from pluripotent stem cells. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;Suppl 10:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paik DT, Rai M, Ryzhov S, Sanders LN, Aisagbonhi O, Funke MJ, Feoktistov I, Hatzopoulos AK. Wnt10b gain-of-function improves cardiac repair by arteriole formation and attenuation of fibrosis. Circ Res. 2015;117:804–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryzhov S, Robich MP, Roberts DJ, Favreau-Lessard AJ, Peterson SM, Jachimowicz E, Rath R, Vary CPH, Quinn R, Kramer RS, Sawyer DB. ErbB2 promotes endothelial phenotype of human left ventricular epicardial highly proliferative cells (eHiPC). J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;115:39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.