Abstract

Introduction

Heated tobacco products (HTPs) are being marketed in several countries around the world with claims that they are less harmful than combusted cigarettes, based on assertions that they expose users to lower levels of toxicants. In the USA, Philip Morris International (PMI) has submitted an application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016 seeking authorisation to market its HTPs, IQOS, with reduced risk and reduced exposure claims.

Methods

We examined the PMI’s Perception and Behavior Assessment Studies evaluating perceptions of reduced risk claims that were submitted to the FDA and made publicly available.

Results

Qualitative and quantitative studies conducted by PMI demonstrate that adult consumers in the USA perceive reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims.

Conclusion

The data in the PMI modified risk tobacco product IQOS application do not support reduced risk claims and the reduced exposure claims are perceived as reduced risk claims, which is explicitly prohibited by the FDA. Allowing PMI to promote IQOS as reduced exposure would amount to a legally sanctioned repeat of the ‘light’ and ‘mild’ fraud which, for conventional cigarettes, is prohibited by the US law and the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

Keywords: advertising and promotion, non-cigarette tobacco poroducts, packaging and labelling, tobacco industry

Introduction

Heated tobacco products (HTPs), also called heat-not-burn products, are tobacco products that heat tobacco to temperatures that avoid combustion and produce a nicotine aerosol that is inhaled by smokers and may also generate side-stream emissions.1 As of February 2018, HTP entrants into the global market included Philip Morris International’s (PMI)’s ‘IQOS’, British American Tobacco’s ‘Glo’, Japan Tobacco’s ‘Ploom Tech’ and RJ Reynolds’ revamped ‘Eclipse’. Because of the growing evidence of severe negative health effects of smoking and smokers’ concerns about their health, tobacco companies have been motivated to create ‘safer cigarettes’ since the 1960s, and in 1988 they first introduced HTPs, marketing them as less harmful than combusted cigarettes. While HTPs produce different toxic chemicals than combusted cigarettes,2 the human health effects of HTPs are not completely understood and the evidence that PMI submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revealed that, in terms of the clinical biomarkers of disease3 or pulmonary and immune toxicity,4 IQOS was not significantly different from cigarettes.

As of February 2018, the new HTPs, like PMI’s IQOS, were being sold in multiple countries around the world in minimalist high-tech looking stores that resemble Apple stores.5–7 Advertisements and marketing materials for IQOS emphasise both its superiority over combustible cigarettes (in terms of cleanliness and customisability) and similarity to them (in terms of product’s taste, size and providing similar behavioural experience).6 Claims about health benefits or lower risks of IQOS are not emphasised in the marketing materials and some of the materials carry minimal health warnings, such as ‘This tobacco product can harm your health and is addictive’6 or it is ‘not risk-free or a safe alternative to cigarettes but it is a much better choice than smoking.’7 Before IQOS is introduced into the US market, PMI needs the FDA’s permission. The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act8 (FSPTCA) assigns the FDA authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing and distribution of tobacco products in the USA. Tobacco manufacturers may seek authorisation from FDA to market products with claims that they reduce risks of tobacco-related diseases compared with other tobacco products currently on the market.

To obtain FDA authorisation to market a product as a ‘modified risk tobacco product’ (MRTP), a company must submit an MRTP application to FDA. FDA may issue one of two types of orders permitting such marketing: (1) a ‘risk modification order’ or (2) an ‘exposure modification order’.9 10 For a risk modification order, a company must provide scientific evidence that the product ’as actually used by consumers will (1) significantly reduce harm and the risk of tobacco-related disease to individual users and (2) benefit the health of the population as a whole taking into account both users of tobacco products and persons who do not currently use tobacco products.'10 When such scientific evidence is not available and cannot be obtained without long-term epidemiological studies, an exposure modification order can be issued if the company demonstrates that such an order would be appropriate for promoting public health (once again taking into account both users and non-users) and that lower levels of harmful chemicals in the product will likely result in reduced death and disease among individual tobacco users. Under the exposure modification order, the marketing claim can only state that the product has lower levels of or is free of a certain substance. Furthermore, a company needs to demonstrate that “consumers will not be misled into believing that the product is […] less harmful or presents […] less of a risk of disease than one or more other commercially marketed tobacco products.”9 The FSPTCA puts the burden on the MRTP applicant, not the FDA, to demonstrate that the product presents reduced risk or reduced exposure and to demonstrate that consumers do not perceive reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims.

Long before the MRTP process was enacted in 2009, tobacco companies had been misleading the public with reduced exposure claims since the 1950s, asserting that filtered and low-tar cigarettes11 gave smokers ‘less tar and nicotine’,12 a reduced exposure claim. ‘Light’ and ‘mild’ cigarettes have been marketed to smokers concerned about their health and positioned as an alternative to quitting smoking.13–15 Even though advertisements for light and mild cigarettes almost never explicitly stated that they would reduce risk of tobacco-related disease, people who saw these advertisements with reduced exposure claims perceived these cigarettes to have lower health risks than regular cigarettes.16 17

Furthermore, these cigarettes did not result in lower levels of exposure to harmful chemicals for users. Tobacco companies created them with microscopic ventilation holes in the filters to draw in air and reduce machine-measured tar and nicotine, which gave the appearance that these products delivered lower emissions to the user.18 19 However, the cigarette companies designed these products so that smokers would compensate for dilution of the smoke by blocking ventilation holes with their lips, taking larger puffs or taking more frequent puffs.20–23

This inherently deceptive nature of reduced exposure and reduced risk (‘light’ and ‘mild’) marketing claims was at the core of the US Department of Justice’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization (RICO) Act lawsuit against the major cigarette companies for defrauding the public about the dangers of smoking and which essentially became the basis of the FSPTCA’s MRTP provisions. In August 2006, Federal Judge Gladys Kessler held24 that the tobacco companies, including Philip Morris, violated RICO by fraudulently covering up the health risks associated with smoking and for marketing their products to children. Judge Kessler found that the companies “have engaged in and executed – and continue to engage in and execute -- a massive 50 year scheme to defraud the public, including consumers of cigarettes, in violation of RICO [emphasis added].” In her 1683-page opinion with extensive Findings of Fact, Judge Kessler found, among other fraudulent acts, that Philip Morris and other tobacco companies deceptively marketed cigarettes characterised as ‘light’ or ‘low tar’, while knowing that those cigarettes were at least as hazardous as ‘full flavoured’ cigarettes; misled smokers, former smokers and non-smokers to believe that these cigarettes were safer and deliberately targeted the youth market (see table 1 for examples of relevant findings). Importantly, the court found that there was a reasonable likelihood that defendants would continue to violate RICO in future.

Table 1.

Relevant findings from Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization case

| “According to [Brand Manager of Marlboro from 1969 to 1972, James] Morgan, Philip Morris made a calculated decision to use the phrase ‘lower tar and nicotine’ even though its own marketing research indicated that consumers interpreted that phrase as meaning that the cigarettes not only contained comparatively less tar and nicotine, but also that they were a healthier option." | 24 Para 2402, p. 888 |

| “Morgan, who later became CEO of Philip Morris, further explained in 2002 that rather than relying on the tar and nicotine numbers from the FTC Method, ‘the major influence in people’s perceptions in the tar of a cigarette would have come from the marketing positioning of a brand as opposed to people literally reading the FTC [tar and nicotine figures].” | 24 Para 2403, p. 888 |

| Philip Morris and the other tobacco companies knew that “many smokers who were concerned and anxious about the health risks from smoking would rely on the health claims made for low tar cigarettes as a reason, or excuse, for not quitting smoking" | 24 Para 2627, p. 971 |

Following the 2006 RICO decision, in 2009, Congress recognised and described the tobacco companies’ use of reduced exposure claims to mislead the public and Judge Kessler’s findings in 14 of the 49 Findings for the FSPTCA.10 Of particular relevance, Congressional Finding 40 states: “The dangers of products sold or distributed as modified risk tobacco products that do not in fact reduce risk are so high that there is a compelling governmental interest in ensuring that statements about modified risk tobacco products are complete, accurate, and relate to the overall disease risk of the product."

Given the long history of the tobacco industry using reduced exposure claims to mislead consumers into believing that the products in question have reduced risk, most notably through the use of ‘light’ and ‘mild’ cigarette claims, it is important to evaluate to what extent the modified risk claims for the new HTP products are based on scientific evidence and whether reduced exposure claims are perceived by consumers as reduced risk claims. This paper uses the materials in the PMI MRTP application made public by the FDA to evaluate these claims.

Methods

We examined the materials in the PMI MRTP applications to FDA25 for its HTP IQOS system and Heatstick products (PMI also refers to IQOS as Tobacco Heating System (THS) 2.2 in these materials). On 5 December 2016, PMI submitted its MRTP applications asking the FDA to authorise marketing of IQOS with reduced risk and reduced exposure claims. Our analysis is based on the Executive Summary26 and Module 7: Scientific Studies and Analyses,27 specifically Section 7.3 Studies in Adult Human Subject (7.3.2 Perception and Behavior Assessment (PBA) Studies), studies THS-PBA-02-US, THS-PBA-03-US, THS-PBA-04-US and THS-PBA-05-REC-US. We report PMI’s findings on the consumer perceptions of reduced exposure claims.

Results

To develop and evaluate marketing messages and materials with reduced risks and reduced exposure claims, PMI conducted Consumer PBA Studies (table 2). Participants were recruited by phone from proprietary databases maintained by local research agencies, which include people interested in participating in market research. Participants’ smoking status was based on self-report.

Table 2.

Philip Morris International’s (PMI)’s Consumer Perception and Behavior Assessment (PBA) Studies in the USA

| Study name | Methodology | Location | Study year | Participants | Age | Materials |

| THS-PBA-02-US | Qualitative 20 focus groups (n=113) 37 individual interviews |

Boston, MA Chicago, IL Charlotte, NC Phoenix, AZ |

Oct–Dec 2013 | S-NITQ, S-ITQ, FS, NS* |

21+ | Nine potential ‘plain text’† messages‡ |

| THS-PBA-03-US | Quantitative (n=1713) | Chicago, IL Marlton, NJ Phoenix, AZ Atlanta, GA |

Oct–Dec 2014 | S-NITQ, S-ITQ, FS, NS | LA+ | Three potential ‘plain text’† messages selected from THS-PBA-02-US |

| THS-PBA-04-US | Qualitative 28 individual interviews |

Chicago, IL Phoenix, AZ |

Dec 2014 | AS, FS, NS | 18+ | Five potential branded§ communication materials with claims selected from THS-PBA-02-US |

| THS-PBA-05-RRC-US | Quantitative (n=2255) | Paramus, NJ Dallas, TX St Louis, MO Los Angeles, CA |

Jul 2015 | S-NITQ, S-ITQ, FS, NS | LA+ | Three branded§ communication materials with claim #1 ‘Reduced risks of tobacco-related diseases’ |

| THS-PBA-05-RRC2-US | Quantitative (n=2247) | Marlton, NJ Chicago, IL Tampa, FL Denver, CO |

Sep 2015 | S-NITQ, S-ITQ, FS, NS | LA+ | Three branded§ communication materials with the claim #2—‘Reduced risk of harm’ |

| THS-PBA-05-REC-US | Quantitative (n=2272) | Framingham, MA San Diego, CA St Louis, MO Baltimore, MD |

Dec 2015 | S-NITQ, S-ITQ, FS, NS | LA+ | Three branded§ communication materials with the claim #3 ‘Reduced body’s exposure to harmful and potentially harmful chemicals’ |

*Never smokers participated only in Phase 2 of THS-PBA-02-US.

†‘Plain text’ message describes the information communicated on the product.

‡The table in the PMI document says nine messages, but the file (Online Supplementary 1) for Phase 1 shows 13 messages because there are two versions of some (A1, A2, B, C1, C2, D and so on). Phase 2 tested seven messages (Online Supplementary 2).

§The branded communication materials were brochure, pack and direct mail piece with iQOS commercial name and the Tobacco Sticks as HeatSticks with the Marlboro Brand.

AS, adult smokers; FS, adult former smokers; LA, legal smoking age; NS, adult never smokers; S-ITQ, adult smokers with the Intention to quit; S-NITQ, adult smokers with no intention to quit.

Source: adapted from table 1 Overview of the Studies from PMI Research and Development51 (p. 7).

tobaccocontrol-2018-054324supp001.pdf (432.7KB, pdf)

tobaccocontrol-2018-054324supp002.pdf (413.1KB, pdf)

Qualitative studies

PMI’s qualitative studies (THS-PBA-02-US and THS-PBA-04-US) were conducted by TNS Qualitative. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted in person, in facilities with one-way mirrors with PMI representatives observing the studies. They followed discussion guides and employed ‘visual aids’ to position products on relative risk and interest to use scales. Focus groups lasted 2.5 hours, while individual interviews took 1.5 hours. Participants evaluated various messages containing either reduced exposure or reduced risk claims. In THS-PBA-02-US, they evaluated 13 messages in focus groups in Phase 1 (Online Supplementary 1), which were subsequently modified into seven messages for testing with individual interviews in Phase 2 (Online Supplementary 2).

Participants frequently equated reduced exposure claims with reduced risk, conflating the reduction in chemicals with lower chances of developing tobacco-related health issues. For example, female smoker (21–34 years old, Phoenix) stated: "It reduces your body’s exposure to the chemicals… that would be my biggest take-away… it suggests that it is better for you than a traditional cigarette." When asked to clarify: (Better—In what way?), she specified: “It’s the lesser of two evils; it’s a better bad choice… It reduces harmful chemicals which is likely to reduce your chances of getting a tobacco-related disease."

While the PMI’s claims that reduced exposure does not mean reduced harm tried to address this issue, some people found this juxtaposition of a claim of reduced exposure and no reduced harm confusing and hard to believe, which reduced credibility of the message source. Female smoker (21–35 years old, Boston) explained: "It says to me that if you smoke this or if you use this thing, you’re still at risk of getting all those diseases that they claim it reduces your exposure to… The way it’s worded… I’m not buying into it. It’s kind of doubletalk… […] It’s flip flopping, saying it will reduce but you still might get it, or … It’s just weird, it doesn’t make me want to use it at all, now that I’m reading this… This makes me less likely to use it, because I’m… almost mad that it tries to claim that it… has benefits, but it really doesn’t."

The THS-PBA-02-US Study report concludes that all messages (both reduced risk and reduced exposure claims) were perceived by participants as statements about lower harm. In Phase 2, three out of seven messages were reduced exposure claims. For all three reduced exposure messages, the PMI’s report stated that participants perceived IQOS to be a lower risk than conventional cigarettes because the tobacco is heated, not burned, which results in reduced ‘exposure to harmful chemicals’ (pp. 31, 34) and ‘the absence of smoke and second-hand smoke’ (p. 37).28 For the four reduced risk messages, the report similarly concluded that the product was ‘perceived to be a lower risk than conventional cigarettes’ (pp. 40, 42, 44, 46) by ’reducing the production of harmful chemicals found in cigarette smoke and providing a possible chance of reducing the risk of tobacco-related diseases’ (pp. 44, 46).28

The fact that PMI’s report does not distinguish perception of reduced risk and reduced exposure provides additional evidence that reduced exposure claims are viewed as reduced risk claims.

The findings from the second qualitative study (THS-PBA-04-US) that assessed reduced risk and reduced exposure claims in the context of marketing materials (brochure, pack and direct mail) portray a similar picture. The study report concludes that “There is a clear recognition that this is an innovative product that heats, rather than burns, the tobacco using electronic technology combining the tobacco taste satisfaction of CC’s [conventional cigarettes] with hygiene benefits (less odor, no ash, less mess) and the potential to reduce the risk to health compared to smoking conventional cigarettes.”29 Also, "Understanding is generally consistent across all label, labeling and marketing material and subject groups.”29

In this second qualitative study, reduced exposure claims in combination with the information that IQOS does not reduce risk of tobacco-related disease (presented as ‘Important Warning’) were also perceived as confusing and contradictory, but still made participants rate the risk as moderate, below the risk of conventional cigarettes. Some participants were able to articulate that reduced exposure does not mean reduced risk:

“It’s still as risky as smoking a cigarette. It does not mean a reduction in the risk of developing tobacco related diseases…Tobacco related diseases are what you get from smoking cigarettes. It’s telling me that even though it scientifically reduces my body’s exposure to these chemicals, I have the exact same risk of developing a tobacco-related disease." (female adult smoker, 26–35 years old, Chicago).

Yet others were still very optimistic about the product that offers reduced risk, particularly appreciating the implications of reduced exposure as the ability to use HTPs in smoke-free places:

“There’s still a risk, so we all know we can’t get anywhere besides-you can’t get anywhere, you can’t even hide from that, so there’s going to be risk. But it’s just a better way of smoking a cigarette. It gives you a better option. ‘Real tobacco, no fire, tobacco heating system’, so obviously trying to make it a better way of smoking, make it better for you to smoke at your workplace, school, anywhere. So yeah, that’s what I get from it. Well, they give you the less odor, no fire. It even tells you-it gives you a little hint that it will be better for the people that’s around you worrying about affecting them, so that’s good." (male adult smoker, 18–25 years old, Phoenix).

In summary, PMI’s qualitative studies demonstrate that US adults understand reduced exposure claim to mean that the lower levels of harmful chemicals in the product means reduced risk of health harms.

Quantitative studies

PMI reports results of two quantitative studies (THS-PBA-03-US and THS-PBA-05-REC-US, see table 2 for details) that were conducted by Covance Market Access Service. Quantitative studies were five-arm parallel group experiments, where each arm corresponded to the different message condition tested in the study. Studies used computer-assisted self-interviews (with computer-assisted personal interviews for more in-depth questions in THS-PBA-03-US) and lasted 45 min on average. The outcome measures used in these studies are presented in table 3. For the purpose of our study, we focus on the measures PMI used to assess global comprehension and risk perceptions because they indicate to what extent reduced exposure claims are perceived as reduced risk claims.

Table 3.

Outcome measures in quantitative studies

| Construct | Instrument | Example question |

| Intent to Use | The Intent to Use Questionnaire

|

Based on what you know about IQOS, how likely or unlikely are you to try IQOS? If you try IQOS and like it, and taking into consideration the prices that are shown on the material, how likely or unlikely are you to use IQOS regularly? |

| Change in Intention to Quit Smoking | Yes/No questions based on Prochaska and DiClemente’s Stages of Change model (Prochaska and DiClemente 1982) measured before and after exposure to THS 2.2 message to determine change in Intention to Quit Smoking (four items). | Are you seriously considering quitting smoking within the next 6 months? |

| Comprehension |

|

|

| Risk Perception | The Perceived Risk Instrument-Personal Risk comprised of two domains, each measured by a unidimensional scale:

|

|

Source: adapted from table 17 in the Executive Summary, p. 121.26

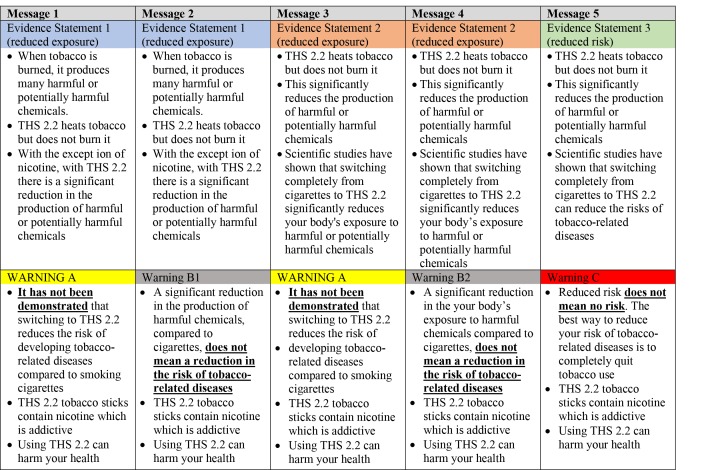

In THS-PBA-03-US, five different text-based messages were evaluated: four contained reduced exposure claims and one had a reduced risk claim (figure 1). Participants were randomised into five groups, where each group saw one of the messages. For the measure of global comprehension, the proportion selecting the answer ‘Reduces the risk of tobacco-related diseases’ was 18% for reduced exposure Message 3, 28% (Message 2), 32% (Message 1) and 35% (Message 4). For all perceived risk measures (health risk to self (figure 3), addiction risk and risk to others), participants rated IQOS lower in risk than cigarettes for all messages, whether it was a reduced exposure message or a reduced risk message.

Figure 1.

Reduced exposure and reduced risk messages used in study THS-PBA-03-US. Note: same messages are indicated by the same colour. PBA, Perception and Behavior Assessment.

Figure 3.

Participants in a quantitative study (THS-PBA-03-US, top panel) perceived health risk of IQOS to be significantly lower than health risks of combusted cigarettes, regardless of whether they saw a reduced exposure claim (Messages 1–4) or a reduced risk claim (Message 5)31 (p. 68). Similarly, participants in THS-PBA-05-REC-US (bottom panel) rated perceived health risks of IQOS lower than combusted cigarettes for all marketing materials with reduced exposure claim30 (pp. 56, 72, 86). Note: answers were no risk, low risk, moderate risk, high risk, very high risk and don’t know and were later converted into a 0–100 scale (0=no risk and 100=very high risk). Error bars represent 95% CIs from the mean. Connecting lines are only to highlight clustering of outcomes for each comparator along the y-axis across IQOS messages. Abbreviations for Smoking Status Group: FS, adult former smokers; LA-25 NS, adult never smokers aged between their state legal smoking age (18 or 21) to 25 years; NS, adult never smokers; PBA, Perception and Behavior Assessment; PMI, Philip Morris International; SG, Surgeon General; S-ITQ, adult smokers with the intention to quit combusted cigarettes; S-NITQ, adult smokers with no intention to quit combusted cigarettes.

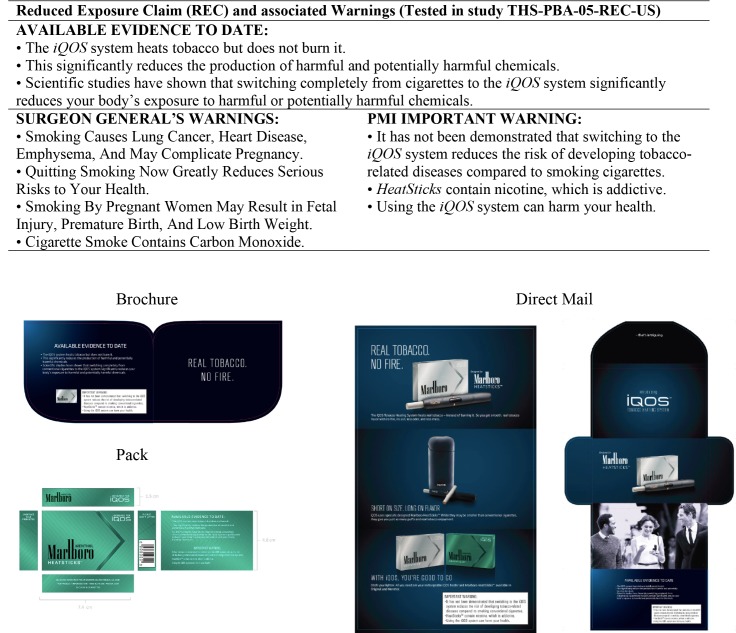

In THS-PBA-05-REC-US, participants evaluated marketing materials with a reduced exposure warning: a brochure, a pack and a direct mail piece (figure 2). In this study, all materials had a reduced exposure claim, but it was paired with either a Surgeon General (SG) warning for cigarettes or a PMI-developed warning for IQOS communicating that reduced exposure does not mean reduced risk, that IQOS contains addictive nicotine and that IQOS can be harmful (‘PMI Important Warning’ in figure 2). Participants were randomised into five groups: (1) brochure with SG warning, (2) brochure with PMI warning, (3) pack with the SG warning, (4) pack with PMI warning and (5) direct mail piece with PMI warning.

Figure 2.

Reduced exposure message and an example of marketing materials from study THS-PBA-05-REC-US. In study THS-PBA-05-REC-US, all marketing materials carried a reduced exposure claim. PBA, Perception and Behavior Assessment; PMI, Philip Morris International.

Between 26% of participants (brochure with a PMI warning) and 58% (pack with SG warning) selected an answer that using IQOS reduces the risk of tobacco-related diseases for the global comprehension measure. An additional 0.8–2.6% answered that it ‘eliminates the risk of tobacco-related diseases.’ The proportion of participants who answered ‘don’t know’ was 3.1–12.3%. In sum, a large proportion of participants who saw the reduced exposure messages selected answers indicating that tobacco-related disease risk is reduced by switching from cigarettes to IQOS.

For the measures of perceived risk to self, IQOS was rated lower than cigarettes. IQOS was rated similar in perceived risks to e-cigarettes for all measures of perceived risk (figure 3).

Participants also consistently rated IQOS as lower in perceived risk of addiction than combusted cigarettes, even though the marketing brochure did not contain any information on how IQOS compared with cigarettes in terms of addiction risk. PMI’s report speculated that participants might be inferring lower perceived addiction risk for IQOS based on the information about reduced exposure to harmful chemicals.30

PMI’s study report31 concluded, "In general, reduced exposure messages may present a greater challenge than reduced risk messages on comprehension of disease risk" (p. 74). “It appears likely that consumers will typically infer a degree of reduced disease risk, even where such inferences are explicitly contradicted by warning statements" (p. 76).31 The report suggested that reduced exposure claims for IQOS “may present an apparent contradiction between (1) reductions in HPHCs [harmful or potentially harmful chemicals identified by the FDA in conventional cigarettes] and (2) a lack of reduced risk for disease" where participants have a hard time reconciling these claims. The report referred the FDA MRTP Draft Guidance, which also acknowledged that “there may be challenges to constructing appropriate claim language that conveys the potential benefits of the product to tobacco users and does not convey that the product is less harmful than other tobacco products.9 In summary, PMI’s quantitative studies corroborated the findings from qualitative studies that US adults perceive reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims.

Discussion

PMI proposed to market IQOS with reduced exposure and reduced risk claims in the USA. PMI’s own qualitative and quantitative studies consistently show that reduced exposure claims are likely to be perceived as reduced risk claims and will, therefore, mislead the public. While few studies outside the tobacco industry evaluated consumer perceptions of reduced risk or reduced exposure claims for non-cigarette tobacco products,32–34 the results were similar. El-Toukhy et al 34 found that modified exposure claims reduced perceived risks of snus and e-cigarette products among adults and adolescents. These results indicate that perceptions of exposure and risk are highly correlated and communication about one— either lower risk or lower exposure—reduces perceptions of both risk and chemical exposure.

The conclusion that consumers interpret reduced exposure information as reduced harm seems to hold across different contexts and tobacco products. The tobacco industry’s ‘reduced exposure’ claims are perceived as indicators of lower harm, as demonstrated by the PMI’s studies reviewed here and by research on ‘light’ and ‘mild’ descriptors.16 17 Furthermore, studies on different ways to communicate amounts of harmful chemicals in cigarettes consistently show that consumers misinterpret quantities of harmful chemicals as indicators of health risks.35 36 This misperception holds regardless of the way the information on reduced exposure is presented: graphically, numbers only, or numbers with additional information, such as common use of these chemicals.37

The tobacco industry has a long history of using reduced exposure claims to mislead consumers into believing that the products in question have reduced risk, most notably through the use of ‘light’ and ‘mild’ cigarette claims.24 Therefore, it is particularly important that the FDA and comparable authorities elsewhere in the world take care not to give legal sanction for PMI or other tobacco companies to market their IQOS or other similar products to mislead the public in the same way that it and other tobacco companies have done with earlier products. In particular, IQOS and other HTPs should not be permitted to be marketed with labelling or advertising that claims or implies modified exposure because the PMI’s own studies demonstrate that consumers perceive reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims. Both US law (FSPTCA, 911(g) and 903)10 and the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control38 (FCTC) and FCTC’s Guidelines for Implementation39 prohibit tobacco product labelling that is false or misleading, especially labelling that would mislead consumers to believe that the product is less harmful than other products.40

Even though tobacco companies almost never marketed light and mild cigarettes with explicit claims of reduced health risks, promotions focused on reduced exposure (lower tar and nicotine) made smokers believe they were reducing their health risks by switching to light cigarettes.13–17 Later, tobacco companies went further to promote light and mild cigarettes with aspirational messages, linking light cigarettes to highly desirable places and situations, such as style, relaxation and sophistication.41 PMI is using the same playbook in marketing IQOS around the world by promoting IQOS as sophisticated and aspirational,7emphasising the themes of cleanliness, customisation and sociability.6 Based on what we have learnt from marketing of light cigarettes and natural tobacco,42–44 as well as the results of PMI’s own research, it is likely that these claims will also be understood by consumers as reduced risk claims.34

Limitations and directions for future research

We report findings from PMI’s qualitative and quantitative studies, relying primarily on the summary reports for each study rather than re-analysing the raw data. Our study is limited by the shortcomings of the original studies. For example, it is possible that participants in the qualitative studies perceived reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims in part because they were exposed to all claims during their focus groups or interviews. These studies focused on more intensive message processing under conditions of participants paying attention to the messages. In the real world, these claims might be processed differently, and the resultant perceptions might be different. Future research should investigate how understanding of reduced exposure and reduced risk claims varies under situations of limited attention and unmotivated processing. Combining reduced risk/exposure claims with warning information that comes from a different source (such as the government) might result in differential processing by various people and more studies need to be done with warnings attributed to various sources to evaluate whether the findings were the artefacts of these specific claims.

Another area worth examining is the role of the source of modified risk information. The PMI’s studies do not report on who the consumers attributed the claims to; however, given what we know, understanding whether consumers think this information comes from FDA or from tobacco companies would play an important role. Past research found that consumers (including tobacco users) generally trust FDA and generally distrust tobacco companies.45 Furthermore, attributing reduced risk claims to FDA might make consumers mistakenly believe that the government endorsed these products and further reduce their risk perceptions, resulting in less informed decision making in the marketplace.33

Conclusion

PMI’s MRTP application for IQOS makes reduced risk claims about IQOS that, like its earlier ‘light’ and ‘mild’ claims that were deemed fraudulent in the RICO case, are not substantiated by PMI’s own internal research reported in its application.2–4 Several of the other papers in this supplement indicate that IQOS is not significantly less harmful than combusted cigarettes2–4 46 47 and that while IQOS had lower levels of pulmonary cytotoxicity48 and carcinogens49 than combusted cigarettes, they were higher than those of e-cigarettes. Therefore, the limited evidence on the health risks of HTPs does not support the much lower levels of perceived harm that PMI’s consumer studies found. Even the evidence for the reduced exposure claim is questionable because PMI’s data show higher levels of exposure than conventional cigarettes to some toxins.2

In the MRPT application, PMI makes an argument that the ‘reduction in exposure to toxicants provides the foundation for the reduced harm rationale for this product as an MRTP’, which further indicates that they do not currently have evidence aside from the data on reduced emissions to demonstrate effects on health. However, this is exactly what FDA says is not sufficient to show reduced risk, that is, to demonstrate that IQOS ’significantly reduce[s] harm and the risk of tobacco-related disease to individual users.' On 25 January 2018, the FDA Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) voted not to accept Philip Morris' claims that IQOS is less harmful than cigarettes (with 8 ’No’s and 1 ’Abstain'). The TPSAC found (on an 8 to 1 vote) that the evidence presented by PMI demonstrated its reduced exposure claim, but unanimously rejected the idea that PMI demonstrated that consumers accurately understand the risks of IQOS. The important point is that the evidence from consumer studies clearly indicates that even a reduced exposure claim does not meet the regulatory criteria because consumers will understand such a claim as a reduced risk claim.

PMI’s reduced exposure claims in its labelling and marketing for IQOS and similar claims for HTPs made by other companies are likely to be misunderstood as reduced risk claims. Therefore, FDA and other regulatory agencies in other countries should not permit PMI or any other tobacco company to market IQOS with reduced exposure claims. If PMI and other tobacco companies are allowed to make confusing (if not deliberately deceptive) claims in its labelling and/or advertising, it is likely to result in consumers being misled into believing HTPs are endorsed by regulatory agencies or into misunderstanding HTP’s harmfulness.50 In short, despite PMI’s contradictory statements,26 the actual reports, transcripts and data submitted by PMI to FDA provide substantial evidence that consumers perceive reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims. Allowing PMI to promote IQOS as reduced exposure would amount to a legally sanctioned repeat of the ‘light’ and ‘mild’ fraud which, for conventional cigarettes, is prohibited by the US law and the FCTC.

What this paper adds.

The US Food and Drug Administration can authorise marketing of tobacco products as causing less exposure to harmful chemicals or lowering health risks. The law requires that claims of lower exposure do not mislead the public into believing the product presents reduced risk of health harm.

The evidence in Philip Morris International’s qualitative and quantitative studies submitted as part of its modified risk tobacco product application reveals that adult consumers in the USA perceive reduced exposure claims as reduced risk claims.

Without evidence of reduced risk, claims of lower exposure are inherently misleading because they will be interpreted as reduced risk claims even if they do not explicitly make reduced risk claims.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors conceptualised the study, contributed to the writing and revision and approved the final version of the manuscript. LP and LKL analysed the data.

Funding: This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (P50 CA180890, R00 CA187460) and the National Institute of Drug Abuse and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (P50 DA036128). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the FDA. The funding agencies played no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. O’Connell G, Wilkinson P, Burseg K, et al. Heated tobacco products create side-stream emissions: implications for regulation. J Environ Anal Chem 2015;2:2380–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helen G, ob P, Nardone N, et al. IQOS: examination of Philip Morris International’s claim of reduced exposure. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s30–s36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glantz SA. PMI’s own in vivo clinical data on biomarkers of potential harm in Americans show that IQOS is not detectably different from conventional cigarettes. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s9–s12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moazed F, Chun L, Matthay MA, et al. Pulmonary and immunosuppressive effects of IQOS. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s20–s25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathers A, Schwartz R, O’Connor S, et al. Marketing IQOS in a dark market. Tob Control 2018. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054216. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hair EC, Bennett M, Sheen E, et al. Examining perceptions about IQOS heated tobacco product: consumer studies in Japan and Switzerland. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s70–s73. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim M. Philip Morris International introduces new heat-not-burn product, IQOS, in South Korea. Tob Control 2018;27:e76–e78. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reynolds RJ. Fact sheet. R.J. Reynolds test markets innovative smokeless tobacco product: Camel snus. Bates no. 525006622. 2006. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=hrlm0006

- 9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Modified risk tobacco product applications - draft guidance. 2012. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/UCM297751.pdf

- 10. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Public Law 111-31, U.S. Statutes at Large 123. 2009. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ31/pdf/PLAW-111publ31.pdf

- 11. Fairchild A, Colgrove J. Out of the ashes: the life, death, and rebirth of the "safer" cigarette in the United States. Am J Public Health 2004;94:192–204. 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tobacco Advertisements. Stanford university research into the impact of tobacco advertising. 2017. http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/index.php

- 13. Warner KE, Slade J. Low tar, high toll. Am J Public Health 1992;82:17–18. 10.2105/AJPH.82.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hurt RD, Robertson CR. Prying open the door to the tobacco industry’s secrets about nicotine: the Minnesota Tobacco Trial. JAMA 1998;280:1173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. The dark side of marketing seemingly "Light" cigarettes: successful images and failed fact. Tob Control 2002;11(Suppl 1):i18–31. 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shiffman S, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL, et al. Smokers' beliefs about "Light" and "Ultra Light" cigarettes. Tob Control 2001;10(suppl 1):i17–i23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamilton WL, Norton G, Ouellette TK, et al. Smokers' responses to advertisements for regular and light cigarettes and potential reduced-exposure tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(Suppl 3):353–62. 10.1080/14622200412331320752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hammond D, Fong GT, Cummings KM, et al. Smoking topography, brand switching, and nicotine delivery: results from an in vivo study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1370–5. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kozlowski LT, Dreschel NA, Stellman SD, et al. An extremely compensatible cigarette by design: documentary evidence on industry awareness and reactions to the Barclay filter design cheating the tar testing system. Tob Control 2005;14:64–70. 10.1136/tc.2004.009167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Khouw V, et al. The misuse of ’less-hazardous' cigarettes and its detection: hole-blocking of ventilated filters. Am J Public Health 1980;70:1202–3. 10.2105/AJPH.70.11.1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kozlowski LT, Heatherton TF, Frecker RC, et al. Self-selected blocking of vents on low-yield cigarettes. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1989;33:815–9. 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90476-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sutton SR, Russell MA, Iyer R, et al. Relationship between cigarette yields, puffing patterns, and smoke intake: evidence for tar compensation? Br Med J 1982;285:600–3. 10.1136/bmj.285.6342.600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frost C, Fullerton FM, Stephen AM, et al. The tar reduction study: randomised trial of the effect of cigarette tar yield reduction on compensatory smoking. Thorax 1995;50:1038–43. 10.1136/thx.50.10.1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. United States v. Philip Morris, 449 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D.D.C. 2006).

- 25. Philip Morris International. Scientific update for smoke-free products. 2017. https://www.pmiscience.com/system/files/publications/pmi_scientific_update_may_2017.pdf

- 26. Philip Morris Products S.A. Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) Applications, Section 2.7 Executive Summary https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/MarketingandAdvertising/ucm546281.htm#E

- 27. Philip Morris Products S.A. Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) Applications, Module 7: scientific studies and analyses https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/MarketingandAdvertising/ucm546281.htm#7

- 28. TNS Qualitative. Qualitative study to develop THS 2.2 hypothetical product messages (PBA 02) within the United States. 2014. https://digitalmedia.hhs.gov/tobacco/static/mrtpa/732pba/PBA02.zip

- 29. TNS Qualitative. Qualitative Study to Develop THS 2.2 Potential label, labeling and marketing material (“THS-PBA-04-US”). 2015. https://digitalmedia.hhs.gov/tobacco/static/mrtpa/732pba/PBA02.zip

- 30. PMI Research and Development. Study Report THS-PBA-05-REC-US: quantitative assessement of THS 2.2 Label, labeling and marketing material with reduced exposure claims. 2016. https://digitalmedia.hhs.gov/tobacco/static/mrtpa/732pba/PBA05REC.zip

- 31. PMI Research and Development. Study Report THS-PBA-03-US: study to quantitatively assess THS 2.2 Potential Messages. 2015. https://digitalmedia.hhs.gov/tobacco/static/mrtpa/732pba/PBA03.zip

- 32. Wackowski O, Hammond D, O’Connor R, et al. Smokers’ and E-Cigarette users’ perceptions about e-cigarette warning statements. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:655 10.3390/ijerph13070655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popova L, Ling PM. Nonsmokers' responses to new warning labels on smokeless tobacco and electronic cigarettes: an experimental study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:997 10.1186/1471-2458-14-997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. El-Toukhy S, Baig SA, Jeong M, et al. Impact of modified risk tobacco product claims on beliefs of US adults and adolescents. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s62–s69. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gallopel-Morvan K, Moodie C, Hammond D, et al. Consumer understanding of cigarette emission labelling. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:373–5. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hammond D, White CM. Improper disclosure: tobacco packaging and emission labelling regulations. Public Health 2012;126:613–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pepper JK, Nonnemaker JM, DeFrank JT, et al. Communicating about cigarette smoke constituents: a National US Survey. Tob Regul Sci 2017;3:388–407. 10.18001/TRS.3.4.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Article 11. 2005.

- 39. World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Elaboration of guidelines for implementation of Article 11 of the Convention. 2008.

- 40. Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Heated tobacco product regulation under US law and the FCTC. Tob Control 2018;27:s118–25. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Anderson SJ, Pollay RW, Ling PM. Taking ad-Vantage of lax advertising regulation in the USA and Canada: reassuring and distracting health-concerned smokers. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1973–85. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McDaniel PA, Malone RE. "I always thought they were all pure tobacco": American smokers' perceptions of "natural" cigarettes and tobacco industry advertising strategies. Tob Control 2007;16:e7 10.1136/tc.2006.019638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Byron MJ, Baig SA, Moracco KE, et al. Adolescents' and adults' perceptions of ’natural', ’organic' and ’additive-free' cigarettes, and the required disclaimers. Tob Control 2016;25:517–20. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Czoli CD, Hammond D. Cigarette packaging: Youth perceptions of "natural" cigarettes, filter references, and contraband tobacco. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:33–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weaver SR, Jazwa A, Popova L, et al. Whom do Adults Trust for Health Information on Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems? Social Science & Medicine - Population Health 2017;3:787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nabavizadeh P, Liu J, Havel C, et al. Vascular endothelial function is impaired by aerosol from a single IQOS HeatStick to the same extent as by cigarette smoke. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s13–s19. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chun L, Moazed F, Matthay M, et al. Possible hepatotoxicity of IQOS. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s39–s40. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leigh NJ, Tran PL, O’Connor RJ, et al. Cytotoxic effects of heated tobacco products (HTP) on human bronchial epithelial cells. Tob Control 2018(27(Suppl1):s26–s29. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leigh N, Palumbo M, Marino A, et al. Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines (TSNA) in Heated Tobacco Product IQOS. Tob Control 2018;27(Suppl1):s37–s38. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. World Health Organization. WHO condemns misleading use of its name in marketing of heated tobacco products. 2018.

- 51. PMI Research and Development. THS 6.4 consumer understanding and perceptions. 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Static/widgets/tobacco/MRTP/PMP/PMP_MRTPA_FDA-2017.zip

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tobaccocontrol-2018-054324supp001.pdf (432.7KB, pdf)

tobaccocontrol-2018-054324supp002.pdf (413.1KB, pdf)