Abstract

The systematic positions of two hesperiid genera, Apostictopterus and Barca (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae), remain ambiguous. We sequenced and annotated the two mitogenomes of Apostictopterus fuliginosus and Barca bicolor and inferred the phylogenetic positions of the two genera within the Hesperiidae based on the available mitogenomes. The lengths of the two circular mitogenomes of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor are 15,417 and 15,574 base pairs (bp), respectively. These two mitogenomes show similar AT skew, GC skew, codon usage and nucleotide bias of AT: the GC skew of the two species is negative, and the AT skew of A. fuliginosus is negative, while the AT skew of B. bicolor is slightly positive. The largest intergenic spacer is located at the same position between trnQ and ND2 in A. fuliginosus (73 bp) and B. bicolor (72 bp). Thirteen protein-coding genes (PCGs) start with ATN codons except for COI, which starts with CGA. The control regions of both mitogenomes possess a long tandem repeat, which is 30 bp long in A. fuliginosus, and 18 bp in B. bicolor. Bayesian inference and maximum likelihood methods were employed to infer the phylogenetic relationships, which suggested that A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor belong in the subfamily Hesperiinae.

Introduction

Skipper butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) include approximately 4,000 species in 567 genera worldwide1 and account for a fifth of the world’s butterfly fauna2. Despite considerable efforts in recent years3–5, the higher-level phylogenetic relationships within the family Hesperiidae are still unsatisfactorily resolved. The taxonomic affinities of many genera are not conclusive, even at the subfamily level6, including Apostictopterus and Barca.

The taxonomic positions of the two monotypic genera Apostictopterus and Barca have been controversial. They were assigned to the Heteropterus group of the subfamily Hesperiinae close to the Astictopterus group in Evans’s classification7, while Chou8 assigned Apostictopterus to the tribe Astictopterini and Barca to the tribe Heteropterini. Since Higgins9, the Heteropterus group of Evans has widely been regarded as Heteropterinae at the subfamily level. In previous studies1,10, these two genera were both treated as members of the subfamily Heteropterinae. However, on the basis of morphological evidence, Warren et al.6 were more likely to place them in Hesperiinae.

The difficulty of morphologically based phylogenetic systematics has been shown, whereas molecular phylogeny has been contributing to the development of a more stable classification. Since mitochondria are characterised by maternal inheritance, a rapid evolutionary rate, and little or no genetic recombination, they have been extensively used in the field of genetics and evolutionary biology11–14. Insect mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) are typically compact circular molecules of 15–18 kb containing 37 genes, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and two ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs)15,16. In addition, the mitogenome mostly contains a control region (an AT-rich region due to a high A + T content) that has a longer sequence than the other regions and embraces essential regulatory elements for transcription and replication16–20. However, this region cannot be well sequenced by high-throughput sequencing techniques, as the depth of coverage is strongly positively correlated with the GC content21.

Mitogenomes are data rich and relatively accessible source of information. Condamine21 had obtained promising results on the genus-level relationships of swallowtail butterflies using mitogenomes. Thus far, 30 complete or nearly complete mitogenomes of skippers have been sequenced. In this study, we sequenced two additional complete mitogenomes of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor and then elucidated the composition of the genomes. Finally, we inferred the phylogenetic relationships from the 27 available mitogenomes within the Hesperiidae4,5,22–26. We did not use three mitogenomes. Polytremis jigongi and Polytremis nascens showed very low homology to the other species. There are two mitogenomes of Daimio tethys that are basically in line, so we randomly selected the one from Korea based on a computation-efficient strategy.

Results and discussion

Genome structure and organization

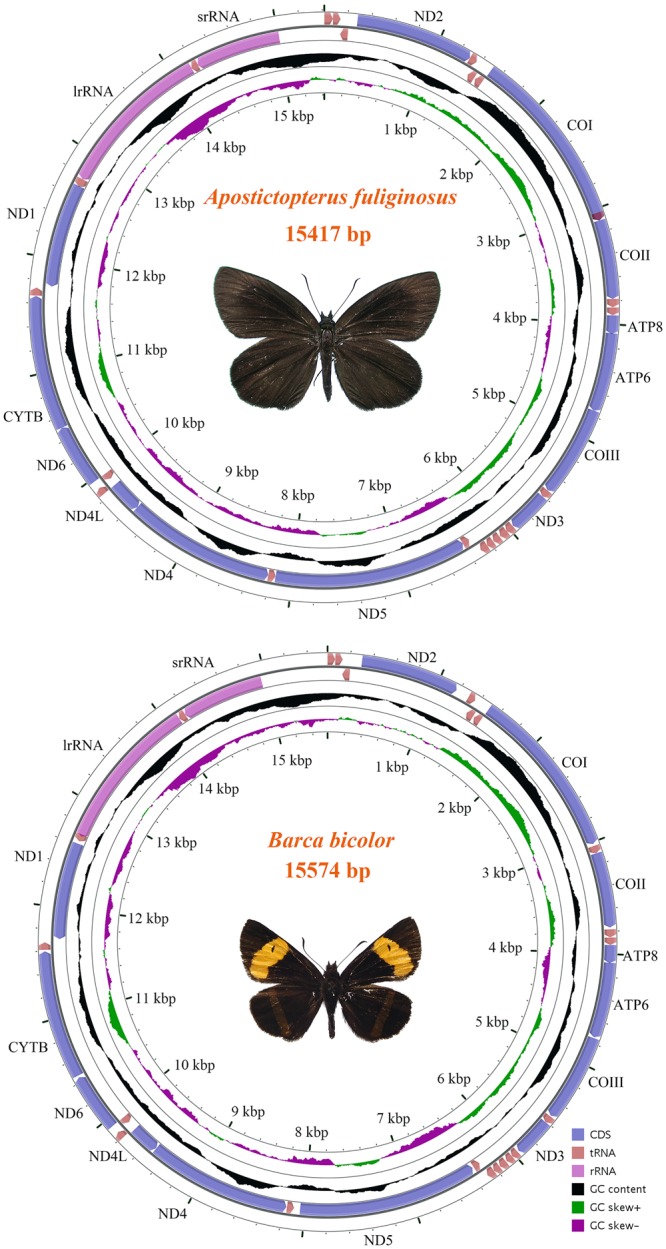

The complete mitogenomes of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor are 15,417 bp and 15,574 bp (Fig. 1), respectively, which are similar to other hesperiid mitogenomes (Table 1). The organisations of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor are shown in Table 1. Similar to most typical insect mitogenomes, these two species harbours 13 protein-coding genes (ATP6, ATP8, Cytb, COI-COIII, ND1-ND6, and ND4L), 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), two ribosomal RNAs (rRNA: lrRNA and srRNA), and an AT-rich region. These assembly units are identical to those of the other skippers, and the encoding protein genes’ ORF direction is the same as in most skippers. Both mitogenomes have 15 intergenic regions. The maximum intervals of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor, both between trnQ with ND2, are 73 bp and 72 bp, respectively. Only a few genes (four PCGs, eight tRNAs, and two rRNAs) are from the N strand, and the remaining 23 genes (nine PCGs and 14 tRNAs) are from the J strand. The nucleotide composition of A. fuliginosus is A (40.1%), T (40.6%), C (11.8%), and G (7.4%); the AT nucleotide content is as high as 80.7%. In B. bicolor, the composition is A (40.0%), T (39.4%), C (12.9%), and G (7.7%); the AT nucleotide content is as high as 79.4%. In these two mitogenomes, the GC skew of two mitogenomes and the AT skew of A. fuliginosus are negatively biased, while the AT skew of B. bicolor has a slightly positive bias (Supplementary Material S1).

Figure 1.

Circular map of the mitogenomes of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor.

Table 1.

Organization of the A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor mitogenomes.

| Specices | Gene | Direction | Location | Size | Anticodon | Start codon | Stop codon | Intergenic nucleotide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apostictopterus fuliginosus | tRNA Met | F | 1–74 | 74 | ATG | 0 | ||

| tRNA Ile | F | 75–138 | 64 | ATC | 3 | |||

| tRNA Gln | R | 142–210 | 69 | CAA | 73 | |||

| ND2 | F | 284–1,297 | 1,014 | ATT | TAA | 1 | ||

| tRNA Trp | F | 1,299–1,363 | 65 | TGA | −8 | |||

| tRNA Cys | R | 1,356–1,420 | 65 | TGC | 12 | |||

| tRNA Tyr | R | 1,433–1,498 | 66 | TAC | 7 | |||

| COI | F | 1,506–3,036 | 1,531 | CGA | T– | 0 | ||

| tRNA Leu | F | 3,037–3,104 | 68 | TTA | 0 | |||

| COII | F | 3,105–3,783 | 679 | ATG | T– | 0 | ||

| tRNA Lys | F | 3,784–3,854 | 71 | AAG | 2 | |||

| tRNA Asp | F | 3,857–3,923 | 67 | GAC | 0 | |||

| ATP8 | F | 3,924–4,082 | 159 | ATT | TAA | −7 | ||

| ATP6 | F | 4,076–4,753 | 678 | ATG | TAA | −1 | ||

| COIII | F | 4,753–5,538 | 786 | ATG | TAA | 2 | ||

| tRNA Gly | F | 5,541–5,607 | 67 | GGA | 0 | |||

| ND3 | F | 5,608–5,961 | 354 | ATT | TAA | 3 | ||

| tRNA Ala | F | 5,965–6,032 | 68 | GCA | −1 | |||

| tRNA Arg | F | 6,032–6,100 | 69 | CGA | 7 | |||

| tRNA Asn | F | 6,108–6,172 | 65 | AAC | 4 | |||

| tRNA Ser | F | 6,177–6,237 | 60 | AGC | 0 | |||

| tRNA Glu | F | 6,238–6,304 | 67 | GAA | 38 | |||

| tRNA Phe | R | 6,343–6,407 | 65 | TTC | 0 | |||

| ND5 | R | 6,408–8,148 | 1,741 | ATT | T– | 0 | ||

| tRNA His | R | 8,149–8,215 | 67 | CAC | 0 | |||

| ND4 | R | 8,216–9,554 | 1,339 | ATG | T– | −1 | ||

| ND4L | R | 9,554–9,838 | 285 | ATG | TAA | 2 | ||

| tRNA Thr | F | 9,841–9,905 | 65 | ACA | 0 | |||

| tRNA Pro | R | 9,906–9,970 | 65 | CCA | 2 | |||

| ND6 | F | 9,973–10,509 | 537 | ATA | TAA | −1 | ||

| Cytb | F | 10,509–11,660 | 1,152 | ATG | TAA | 3 | ||

| tRNA Ser | F | 11,664–11,730 | 67 | TCA | 19 | |||

| ND1 | R | 11,750–12,688 | 939 | ATG | TAA | −6 | ||

| tRNA Leu | R | 12,683–12,757 | 75 | CTA | 0 | |||

| lrRNA | R | 12,758–14,172 | 1,415 | 0 | ||||

| tRNA Val | R | 14,173–14,237 | 65 | GTA | −1 | |||

| srRNA | R | 14,237–15,010 | 774 | −1 | ||||

| AT-rich region | 15,011–15,417 | 407 | 0 | |||||

| Barca bicolor | tRNA Met | F | 1–68 | 68 | ATG | 0 | ||

| tRNA Ile | F | 69–132 | 64 | ATC | 3 | |||

| tRNA Gln | R | 136–204 | 69 | CAA | 72 | |||

| ND2 | F | 277–1,290 | 1,014 | ATT | TAA | 4 | ||

| tRNA Trp | F | 1,295–1,359 | 65 | TGA | 8 | |||

| tRNA Cys | R | 1,352–1,419 | 68 | TGC | 13 | |||

| tRNA Tyr | R | 1,433–1,497 | 65 | TAC | 7 | |||

| COI | F | 1,505–3,035 | 1,531 | CGA | T– | 0 | ||

| tRNA Leu | F | 3,036–3,103 | 68 | TTA | 0 | |||

| COII | F | 3,104–3,782 | 679 | ATG | T– | 0 | ||

| tRNA Lys | F | 3,783–3,853 | 71 | AAG | 1 | |||

| tRNA Asp | F | 3,855–3,920 | 66 | GAC | 0 | |||

| ATP8 | F | 3,921–4,082 | 162 | ATC | TAA | −7 | ||

| ATP6 | F | 4,076–4,753 | 678 | ATG | TAA | −1 | ||

| COIII | F | 4,753–5,538 | 786 | ATG | TAA | 2 | ||

| tRNA Gly | F | 5,541–5,606 | 66 | GGA | 0 | |||

| ND3 | F | 5,607–5,960 | 354 | ATT | TAA | 3 | ||

| tRNA Ala | F | 5,964–6,026 | 63 | GCA | 0 | |||

| tRNA Arg | F | 6,027–6,093 | 67 | CGA | 3 | |||

| tRNA Asn | F | 6,097–6,163 | 67 | AAC | 4 | |||

| tRNA Ser | F | 6,168–6,229 | 62 | AGC | 0 | |||

| tRNA Glu | F | 6,230–6298 | 69 | GAA | −2 | |||

| tRNA Phe | R | 6,297–6,360 | 64 | TTC | 0 | |||

| ND5 | R | 6,361–8,098 | 1,738 | ATT | T– | 0 | ||

| tRNA His | R | 8,099–8,164 | 66 | CAC | −1 | |||

| ND4 | R | 8,164–9,504 | 1,341 | ATG | TAA | −1 | ||

| ND4L | R | 9,504–9,788 | 285 | ATG | TAA | 2 | ||

| tRNA Thr | F | 9,791–9,855 | 65 | ACA | 0 | |||

| tRNA Pro | R | 9,856–9,921 | 66 | CCA | 2 | |||

| ND6 | F | 9,924–10,460 | 537 | ATA | TAA | −1 | ||

| Cytb | F | 10,460–11,611 | 1,152 | ATG | TAA | 1 | ||

| tRNA Ser | F | 11,613–11,678 | 66 | TCA | 18 | |||

| ND1 | R | 11,697–12,635 | 939 | ATG | TAA | −6 | ||

| tRNA Leu | R | 12,630–12,703 | 74 | CTA | 0 | |||

| lrRNA | R | 12,704–14,122 | 1,419 | 0 | ||||

| tRNA Val | R | 14,123–14,187 | 65 | GTA | 0 | |||

| srRNA | R | 14,188–14,960 | 773 | 0 | ||||

| AT-rich region | 14,961–15,574 | 614 | 0 |

In the column intergenic length, the positive number indicates interval base pairs between genes, while the negative number indicates the overlapping base pairs between genes.

Protein-coding genes (PCGs)

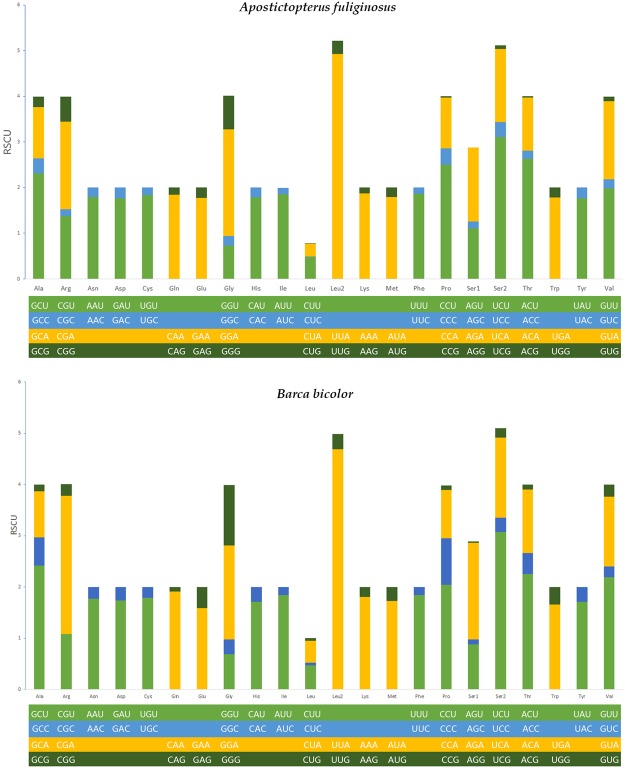

The PCGs of the two mitogenomes encode a total of 3,730 (A. fuliginosus) and 3,731 (B. bicolor) amino acids, which account for 72.6% and 71.9% of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor, respectively. All PCGs in both mitogenomes start with typical ATN codons, except for COI, which is initiated by CGA, as is common in Lepidoptera. Stop codons in the PCGs include two types: TAA or T. Though incomplete stop codons always appear in lepidopteran mitogenomic PCGs, translation will not be affected at all because the codons will be automatically filled by added As during the transcription process27. We calculated the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) of the PCGs in the two mitogenomes (Table 2). According to the RSCU analyses, TTT (F), ATT (I), TTA (L) and ATA (M) were the four most frequently used codons. In both species, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine and serine are the most frequent PCG amino acids (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Codon number and RSCU in the A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor mitochondrial PCGs.

| Specices | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apostictopterus fuliginosus | UUU(F) | 339 | 1.87 | UCU(S) | 123 | 3.11 | UAU(Y) | 165 | 1.77 | UGU(C) | 34 | 1.84 |

| UUC(F) | 23 | 0.13 | UCC(S) | 13 | 0.33 | UAC(Y) | 21 | 0.23 | UGC(C) | 3 | 0.16 | |

| UUA(L) | 462 | 4.93 | UCA(S) | 63 | 1.6 | UAA(*) | 0 | 0 | UGA(W) | 85 | 1.79 | |

| UUG(L) | 27 | 0.29 | UCG(S) | 3 | 0.08 | UAG(*) | 0 | 0 | UGG(W) | 10 | 0.21 | |

| CUU(L) | 45 | 0.48 | CCU(P) | 76 | 2.5 | CAU(H) | 60 | 1.79 | CGU(R) | 18 | 1.38 | |

| CUC(L) | 1 | 0.01 | CCC(P) | 11 | 0.36 | CAC(H) | 7 | 0.21 | CGC(R) | 2 | 0.15 | |

| CUA(L) | 26 | 0.28 | CCA(P) | 34 | 1.11 | CAA(Q) | 63 | 1.85 | CGA(R) | 25 | 1.92 | |

| CUG(L) | 1 | 0.01 | CCG(P) | 1 | 0.03 | CAG(Q) | 5 | 0.15 | CGG(R) | 7 | 0.54 | |

| AUU(I) | 445 | 1.86 | ACU(T) | 104 | 2.63 | AAU(N) | 224 | 1.8 | AGU(S) | 44 | 1.11 | |

| AUC(I) | 33 | 0.13 | ACC(T) | 7 | 0.18 | AAC(N) | 24 | 0.2 | AGC(S) | 6 | 0.15 | |

| AUA(M) | 259 | 1.8 | ACA(T) | 46 | 1.16 | AAA(K) | 109 | 1.88 | AGA(S) | 64 | 1.62 | |

| AUG(M) | 30 | 0.2 | ACG(T) | 1 | 0.03 | AAG(K) | 7 | 0.12 | AGG(S) | 0 | 0 | |

| GUU(V) | 59 | 1.98 | GCU(A) | 70 | 2.31 | GAU(D) | 53 | 1.77 | GGU(G) | 35 | 0.73 | |

| GUC(V) | 6 | 0.2 | GCC(A) | 10 | 0.33 | GAC(D) | 7 | 0.23 | GGC(G) | 10 | 0.21 | |

| GUA(V) | 51 | 1.71 | GCA(A) | 34 | 1.12 | GAA(E) | 64 | 1.78 | GGA(G) | 113 | 2.34 | |

| GUG(V) | 3 | 0.1 | GCG(A) | 7 | 0.23 | GAG(E) | 8 | 0.22 | GGG(G) | 35 | 0.73 | |

| Barca bicolor | UUU(F) | 332 | 1.84 | UCU(S) | 119 | 3.07 | UAU(Y) | 163 | 1.71 | UGU(C) | 35 | 1.79 |

| UUC(F) | 28 | 0.16 | UCC(S) | 11 | 0.28 | UAC(Y) | 28 | 0.29 | UGC(C) | 4 | 0.21 | |

| UUA(L) | 445 | 4.69 | UCA(S) | 61 | 1.57 | UAA(*) | 0 | 0 | UGA(W) | 78 | 1.66 | |

| UUG(L) | 28 | 0.3 | UCG(S) | 7 | 0.18 | UAG(*) | 0 | 0 | UGG(W) | 16 | 0.34 | |

| CUU(L) | 45 | 0.47 | CCU(P) | 65 | 2.04 | CAU(H) | 58 | 1.71 | CGU(R) | 14 | 1.08 | |

| CUC(L) | 5 | 0.05 | CCC(P) | 29 | 0.91 | CAC(H) | 10 | 0.29 | CGC(R) | 0 | 0 | |

| CUA(L) | 41 | 0.43 | CCA(P) | 30 | 0.94 | CAA(Q) | 66 | 1.91 | CGA(R) | 35 | 2.7 | |

| CUG(L) | 5 | 0.05 | CCG(P) | 3 | 0.09 | CAG(Q) | 3 | 0.09 | CGG(R) | 3 | 0.23 | |

| AUU(I) | 417 | 1.84 | ACU(T) | 87 | 2.25 | AAU(N) | 216 | 1.77 | AGU(S) | 34 | 0.88 | |

| AUC(I) | 37 | 0.16 | ACC(T) | 16 | 0.41 | AAC(N) | 28 | 0.23 | AGC(S) | 4 | 0.1 | |

| AUA(M) | 251 | 1.73 | ACA(T) | 48 | 1.24 | AAA(K) | 103 | 1.81 | AGA(S) | 73 | 1.88 | |

| AUG(M) | 40 | 0.27 | ACG(T) | 4 | 0.1 | AAG(K) | 11 | 0.19 | AGG(S) | 1 | 0.03 | |

| GUU(V) | 74 | 2.19 | GCU(A) | 75 | 2.42 | GAU(D) | 53 | 1.74 | GGU(G) | 33 | 0.69 | |

| GUC(V) | 7 | 0.21 | GCC(A) | 17 | 0.55 | GAC(D) | 8 | 0.26 | GGC(G) | 14 | 0.29 | |

| GUA(V) | 46 | 1.36 | GCA(A) | 28 | 0.9 | GAA(E) | 59 | 1.59 | GGA(G) | 87 | 1.83 | |

| GUG(V) | 8 | 0.24 | GCG(A) | 4 | 0.13 | GAG(E) | 15 | 0.41 | GGG(G) | 56 | 1.18 |

Figure 2.

The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in the mt-genomes of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor.

Ribosomal RNA and Transfer RNA genes

The two rRNA genes (lrRNA, srRNA) encoding the small and large ribosomal subunits are located between trnL(CUN) and trnV and between trnV and the AT-rich region. The lrRNA and srRNA lengths are 1,415 and 774 bp, respectively, in A. fuliginosus, and are 1,419 and 773 bp in B. bicolor.

Both A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor have 22 tRNAs with sizes ranging from 62–75 bp, which are systematically embedded in each PCG, rRNA and AT-rich region. The total length of 22 tRNAs is 1,475 bp in A. fuliginosus and 1,475 bp in B. bicolor. Among the 22 tRNAs, 14 are encoded on the J strand and the remaining eight on the N strand, which is in accord with the other lepidopteran mitogenomes28. Most tRNA genes were folded into a cloverleaf secondary structure using MITOS, except for trnS(AGN), which lacks the DHU arm both in A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor (Supplementary Material 2). In many insects, an ancestral status that lacks the DHU stem of trnS(AGN) has been demonstrated29. In addition, the number of bases in the dihydrouridine loop ranges from 4 to 8 bp, which is not uniform because the DHU stem is highly variable30.

Overlapping sequences, intergenic spacers and the control region

There are nine gene overlaps in A. fuliginosus and eight in B. bicolor, with sizes ranging from 1 to 8 bp. The maximum overlap of the two mitogenomes are located between trnW and trnC (Table 1). The length of the common overlap between ATP6 and ATP8, which is widespread in hesperiid mitogenomes18,31,32, is 7 bp both in A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor.

The intergenic spacers of these two skippers are distributed among 15 regions, and their total lengths are 178 bp in A. fuliginosus and 135 bp in B. bicolor. Most of the intergenic spacers are not more than 20 bp. In these two mitogenomes, the longest, but not conserved, spacing sequence, whose position is similar to that in other hesperiid mitogenomes, is located between trnQ and ND2. This is consistent with this spacer probably arising in the process of gene rearrangements23.

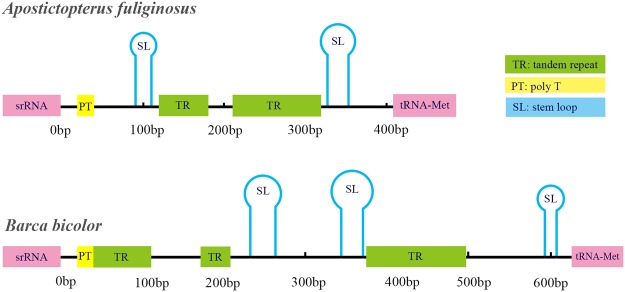

The control region is also called the AT-rich region because it is typically characterised by a high AT content. Moreover, the proportion of the AT content is as high as 94.6% in A. fuliginosus and 92% in B. bicolor. The control regions, the longest region of noncoding sequences that is located between the srRNA and trnM, are 407 bp and 614 bp in A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor, respectively. We found one dinucleotide repeat (TA)55 in A. fuliginosus and two dinucleotide repeats (TA)36 and (AT)54 in B. bicolor. Furthermore, we found a long tandem repeat of 30 bp (AAATAAAAAATTAAAATAATTATTTTAATT) in A. fuliginosus and a tandem repeat length of 18 bp (TAAAAAAATAATTATTTT) in B. bicolor. There was also a structure in the AT-rich region of both species with the poly-T stretch in a position close to the srRNA. Several microsatellite-like A/T sequences following the motif ATTTA in the control region were found in A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor, which were also discovered in the other skipper mitogenomes33. Moreover, our predicted results showed that there are two stem-loop structures in A. fuliginosus and three stem-loop structures in B. bicolor (Fig. 3). Many studies have shown that the motif ATAGA close to the 5ʹ-end of srRNA is greatly conserved23,34. This also exists in A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor.

Figure 3.

Predicted structural elements in the control region of A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor.

Phylogenetic analyses

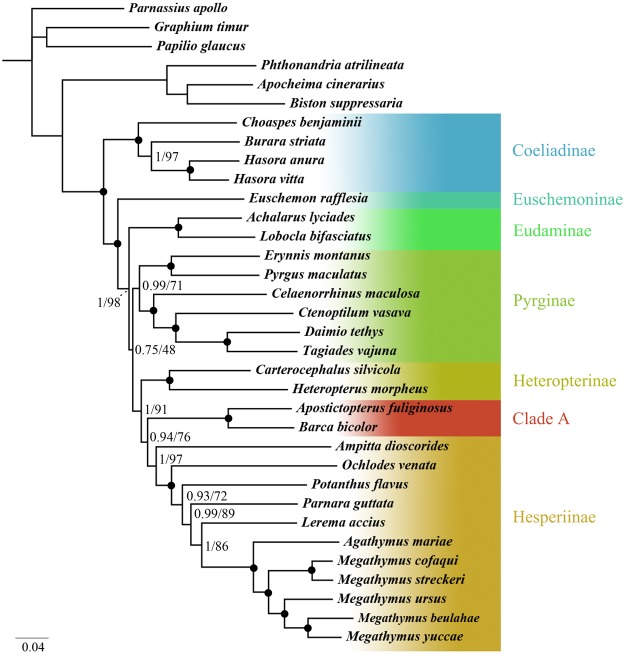

Our datasets included 29 skippers for 14,715 nucleotides after removing ambiguous regions. Different strategies obtained almost the same results (see below); here, we present the results based on the PRT dataset as a basis for subsequent analyses. 16 best-fitting partitioning schemes (Supplementary Material S3) were determined by PartitionFinder with an initial subset of 63 possible partitions based on the PRT dataset.

Similar topologies were inferred from phylogenetic analyses with MrBayes and IQ-TREE (Fig. 4). Six major clades were recovered: Coeliadinae, Euschemoninae, Eudaminae, Pyrginae, Heteropterinae, and Hesperiinae including subclade A, A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor, most of which agree with previous studies1,3,6,10. Coeliadinae is sister to the remaining subfamilies; the systematic positions of Euschemoninae and Eudaminae are confirmed, and Euschemoninae is the sister to all other skippers except Coeliadinae. Pyrginae, containing only four tribes (Erynnini, Pyrgini, Celaenorrhinini and Tagiadini), is recovered as monophyletic with weak support. Hesperiinae is obtained as monophyletic.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree using BI method based on PRT dataset. Numbers at node indicated posterior probabilities (PP) and bootstrap value (BS) based on ML analyses were also given. Dot on nodes means this branch: PP/BS = 1/100.

In the phylogenetic tree, A. fuliginosus and B. bicolor formed a strongly supported subclade (Clade A); this subclade branches after Heteropterinae and is followed by Hesperiinae with high support. Our results do not agree with placing them in the subfamily Heteropterinae1,10. We thus tentatively assign these two genera to the subfamily Hesperiinae. Previous studies have inferred a close relationship among Heteroptinae, Trapezitinae and Hesperiinae, but the sister relationships were uncertain3,6, and none of these studies sampled Apostictopterus and Barca. In this study, we were unable to include Trapezitinae to test for close relationships with Hesperiinae along with Apostictopterus and Barca, as no mitogenome is yet available. Hence, more samples in Trapezitinae are needed to confirm this hypothesis and clarify their systematic positions.

The phylogenetic analyses based on four datasets (PRT, PCGC, PCGD and PCGR) using two methods revealed very similar topologies except for the phylogenetic position of Eudaminae and Pyrginae. In the BI and ML analyses from different datasets, the topologies were largely congruent except for three strategies with little discrepancy. As many studies have concluded, the mitogenome can provide robust and stable phylogenetic analyses. The result from the PCGR dataset showed that Eudaminae branched after Euschemoninae in the BI analyses. In the ML analyses, however, the topologies based on the PCGC and PCGD datasets revealed that Eudaminae nested within Pyrginae (Supplementary Material S4), suggesting that Pyrginae is polyphyletic. Above all, the monophyly of Pyrginae and Eudaminae remains unresolved in our analyses, and more evidence is needed to address this issue.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

The adult specimen of A. fuliginosus was collected in Linzhi, Tibet Autonomous Region, China. The adult B. bicolor specimen was obtained in Weixi Lisu Autonomous County, Yunnan Province, China. Two or three legs from a single specimen were used to extract the genomic DNA using the HiPure Insect DNA Kit (Magen, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Primers, PCR, and cloning

For amplification, the complete mitogenomes were divided into 27 overlapping fragments. The primers were mainly taken from Kim et al.23 except for SF2, SF10, SF18, SF22 and SF27, which are newly designed (Supplementary Material S5). Due to the instability of the AT-rich region, we cloned this fragment after amplification and subsequent sequencing. For cloning, we referred to Fan et al.35.

We amplified all of the mitogenome but AT-rich regions using SuperMix (Transgene, China) via the following protocol: initial denaturation for 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94 °C, annealing for 45 s at 40–50 °C, and extension for 1 min at 72 °C, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. For the AT-rich region, we used KOD high-fidelity thermostable DNA polymerase (Takara, Japan) to improve the accuracy of the amplification and employed the following PCR conditions: initial denaturation of 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 10 s at 98 °C, annealing for 45 s at 42 °C, and extension for 1 min at 68 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Sequence analysis and annotation

We assembled and proof-read the sequences using the software Geneious v7.1.436. PCGs were identified by finding the ORFs on the NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) with the invertebrate mitochondrial genetic codes. The tRNAs and rRNAs were identified using the MITOS Web Server (http://mitos.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/index.py)37. Moreover, to confirm the accuracy of the boundaries of different genes, 37 genes were aligned using ClustalW in MEGA v7.0.238 and manual inspection. The nucleotide composition statistics and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) were calculated using MEGA v7.0.2. The AT skew and GC skew39 values used for measuring the deviation of the base were calculated by the following formulas: AT skew = (A − T)/(A + T); GC skew = (G − C)/(G + C). The circular maps were drawn by CGView Server (http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/)40. The tandem repeats of the control region were identified with the Tandem Repeats Finder on-line server (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html)15. Stem loop structures of the AT-rich region were predicted by DNAMAN. The two complete mitogenomes were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers MH985707 and MH985708.

Phylogenetic analysis

We downloaded 33 available lepidopteran mitogenomes from GenBank, including 27 Hesperiidae, three Papilionidae and three Geometridae. The species used in this study are listed in Table 3. Each of the 13 PCGs was aligned individually using the software MAFFT V7.31341 with the G-INS-i strategy. Each of the two rRNAs was aligned separately using the Q-INS-i strategy through the MAFFT V7 online alignment server (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/)42. We removed gaps and ambiguous sites from the 13 PCGs by using the Gblocks V0.9143 online server (http://molevol.cmima.csic.es/castresana/Gblocks_server.html) with default settings.

Table 3.

List of butterfly species analyzed in this paper with their respective GenBank accession numbers.

| Species | Family | Size | GBAN* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achalarus lyciades | Hesperiidae | 15,612 bp | NC_030602 |

| Agathymus mariae | Hesperiidae | 15,342 bp | KY630504 |

| Ampittia dioscorides | Hesperiidae | 15,313 bp | KM102732 |

| Apostictopterus fuliginosus | Hesperiidae | 15,417 bp | MH985707 |

| Barca bicolor | Hesperiidae | 15,574 bp | MH985708 |

| Burara striata | Hesperiidae | 15,327 bp | NC_034676 |

| Carterocephalus silvicola | Hesperiidae | 15,765 bp | NC_024646 |

| Celaenorrhinus maculosa | Hesperiidae | 15,282 bp | NC_022853 |

| Choaspes benjaminii | Hesperiidae | 15,300 bp | NC_024647 |

| Ctenoptilum vasava | Hesperiidae | 15,468 bp | NC_016704 |

| Daimio tethys | Hesperiidae | 15,350 bp | NC_024648 |

| Erynnis montanus | Hesperiidae | 15,530 bp | NC_021427 |

| Euschemon rafflesia | Hesperiidae | 15,447 bp | NC_034231 |

| Hasora anura | Hesperiidae | 15,290 bp | NC_027263 |

| Hasora vitta | Hesperiidae | 15,282 bp | NC_027170 |

| Heteropterus morpheus | Hesperiidae | 15,769 bp | NC_028506 |

| Lerema accius | Hesperiidae | 15,338 bp | NC_029826 |

| Lobocla bifasciata | Hesperiidae | 15,366 bp | NC_024649 |

| Megathymus beulahae | Hesperiidae | 15,412 bp | KY630505 |

| Megathymus cofaqui | Hesperiidae | 15,421 bp | KY630503 |

| Megathymus streckeri | Hesperiidae | 15,507 bp | KY630501 |

| Megathymus ursus | Hesperiidae | 15,396 bp | KY630502 |

| Megathymus yuccae | Hesperiidae | 15,477 bp | KY630500 |

| Ochlodes venata | Hesperiidae | 15,622 bp | NC_018048 |

| Parnara guttatus | Hesperiidae | 15,441 bp | NC_029136 |

| Potanthus flavus | Hesperiidae | 15,267 bp | NC_024650 |

| Pyrgus maculatus | Hesperiidae | 15,346 bp | NC_030192 |

| Tagiades vajuna | Hesperiidae | 15,359 bp | KX865091 |

| Apocheima cinerarium | Geometridae | 15,722 bp | NC_024824 |

| Biston suppressaria | Geometridae | 15,628 bp | NC_027111 |

| Phthonandria atrilineata | Geometridae | 15,499 bp | NC_010522 |

| Graphium timur | Papilionidae | 15,226 bp | NC_024098 |

| Papilio glaucus | Papilionidae | 15,306 bp | NC_027252 |

| Parnassius apollo | Papilionidae | 15,404 bp | NC_024727 |

*GenBank accession number.

To compare the phylogenetic signal information of the different dataset combinations, four datasets were used: 1) PCGD: the 13 complete PCGs with the 3rd codon removed; 2) PCGC: the 13 complete PCGs; 3) PRT: the 13 complete PCGs, two rRNAs and 22 tRNAs; and 4) PCGR: two rRNAs and 13 PCGs with the 3rd codon removed. We employed PartitionFinder V2.1.144 to identify the best partitioning strategies under the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed on the IQ-TREE web online server (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/)45 with 1000 ultrafast bootstraps (UFBS) to estimate the branch support. The best-fit models produced by ModelFinder46 implemented in IQ-tree. The Bayesian inference (BI) analyses were performed using MrBayes V3.2.6 on the CIPRES Science Gateway 3.347. We used reversible-jump MCMC to allow sampling across all substitution rate models instead of specifying one substitution model, as suggested by PartitionFinder in BI analysis. Four Markov chains (one cold and three heated chains) were run simultaneously for 1 × 107 generations with sampling every 1,000 generations. We examined the average standard change of the split frequencies in Tracer V1.748 to determine the values falling below 0.01. We discarded the first 25% of the sampled trees as burn-in. The remaining trees were then used to calculate the posterior probabilities (PP) under the majority rule consensus.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Min Wang (South China Agricultural University) for kind help in collecting materials and reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 31471984 and 31172136) to X. F. Two anonymous reviewers are thanked for constructive and insightful suggestions that substantially improved the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Y.H. and X.F. designed the research. Y.H. performed the experiments. Y.H. and Z.H. analyzed the data. Y.H. wrote the early draft of manuscript. Z.H., J.T. and H.C. contribute most to the revision. Y.H., Z.H. and X.F. discussed results and discussion. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuke Han and Zhenfu Huang contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-34107-1.

References

- 1.Warren AD, Ogawa JR, Brower AVZ. Phylogenetic relationships of subfamilies and circumscription of tribes in the family Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea) Cladistics. 2008;24:642–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00218.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernández-Roldán JL, Bofill R, Dapporto L, Munguira ML, Vila R. Morphological and chemical analysis of male scent organs in the butterfly genus Pyrgus (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Org. Divers. Evol. 2014;14:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s13127-014-0170-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahoo RK, et al. Ten genes and two topologies: an exploration of higher relationships in skipper butterflies (Hesperiidae) Peer J. 2016;4:e2653. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cong Q, Grishin NV. The complete mitochondrial genome of Lerema accius and its phylogenetic implications. Peer J. 2016;4:e1546. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang, J. et al. Mitogenomes of giant-skipper butterflies reveal an ancient split between deep and shallow root feeders. F1000Research6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Warren AD, Ogawa JR, Brower AVZ. Revised classification of the family Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea) based on combined molecular and morphological data. Syst. Entomol. 2009;34:467–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2008.00463.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans, W. A Catalogue of the Hesperiidae from Europe, Asia, and Australia in the British Museum (Natural History) (Trustees of the British Museum, London, 1949).

- 8.Chou, I. Classification and Identification of Chinese Butterflies (Henan Scientific and Technological Press, Zhengzhou, 1998).

- 9.Higgins, L. G. Classification of European Butterflies (Collins Press, Cork, 1975).

- 10.Yuan, F., Yuan, X. Q. & Xue, G. X. Fauna Sinica. (Insecta Vol. 55 Lepidoptera, Hesperiidae) (China: Science Press, Beijing, 2015).

- 11.Simon C, Buckley TR, Frati F, Stewart JB, Beckenbach AT. Incorporating molecular evolution into phylogenetic analysis, and a new compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers for animal mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2006;37:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song N, Liang AP, Bu CP. A molecular phylogeny of Hemiptera inferred from mitochondrial genome sequences. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, et al. Higher-level phylogeny of paraneopteran insects inferred from mitochondrial genome sequences. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8527. doi: 10.1038/srep08527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avise JC. Phylogeography: retrospect and prospect. J. Biogeogr. 2009;36:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02032.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron SL. Insect mitochondrial genomics: implications for evolution and phylogeny. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014;59:95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolstenholme DR. Animal mitochondrial DNA: structure and evolution. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992;141:173. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang ST, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the giant silkworm moth, Eriogyna pyretorum (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009;5:351. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fauron CMR, Wolstenholme DR. Extensive diversity among Drosophila species with respect to nucleotide sequences within the adenine+thymine-rich region of mitochondrial DNA molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:2439–2452. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.11.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang DX, Jacek MS, Godfrey MH. Evolution and structural conservation of the control region of insect mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;40:382–391. doi: 10.1007/BF00164024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Condamine FL, Nabholz B, Clamens A, Dupuis JR, Sperling FAH. Mitochondrial phylogenomics, the origin of swallowtail butterflies, and the impact of the number of clocks in Bayesian molecular dating. Syst. Entomol. 2018;43:460–480. doi: 10.1111/syen.12284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen J, Cong Q, Grishin NV. The complete mitogenome of Achalarus lyciades (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2016;1:581–583. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2016.1197070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim MJ, Wang AR, Park JS, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genomes of five skippers (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) and phylogenetic reconstruction of Lepidoptera. Gene. 2014;549:97–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, Hao J, Zhao H. Characterization of complete mitochondrial genome of the skipper butterfly, Celaenorrhinus maculosus (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2013;26:690–691. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.840610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang AR, Jeong HC, Han YS, Kim I. The complete mitochondrial genome of the mountainous duskywing, Erynnis montanus (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae): a new gene arrangement in Lepidoptera. Mitochondrial. DNA. 2013;25:93–94. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.784752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, et al. The complete mitogenome of Euschemon rafflesia (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2:136–138. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1292478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ojala D, Julio M, Giuseppe A. TRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature. 1981;290:470. doi: 10.1038/290470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xin ZZ, et al. Mitochondrial genomes of two Bombycoidea insects and implications for their phylogeny. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garey JR, David RW. Platyhelminth mitochondrial DNA: evidence for early evolutionary origin of a tRNAserAGN that contains a dihydrouridine arm replacement loop, and of serine-specifying AGA and AGG codons. J. Mol. Evol. 1989;28:374–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02603072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tajima F. Simple methods for testing the molecular evolutionary clock hypothesis. Genet. Soc. Am. 1993;135:599–607. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu BJ, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Diaphania pyloalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralididae) Gene. 2013;527:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen MM, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of the atlas moth, Attacus atlas (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) and the phylogenetic relationship of Saturniidae species. Gene. 2014;545:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron SL, Whiting MF. The complete mitochondrial genome of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within butterflies and moths. Gene. 2008;408:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu QN, et al. A transfer RNA gene rearrangement in the lepidopteran mitochondrial genome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;489:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan XL, et al. Clarification of the phylogenetic framework of the tribe Baorini (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae: Hesperiinae) inferred from multiple gene sequences. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernt M, et al. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;69:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perna N, Kocher T. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;41:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF01215182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView Server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W181–W184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT Multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J. & Yamada, K. D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;34:772–773. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen L, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller, M. A., Pfeiffer, W. & Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE) 1–8 (2010).

- 48.Huang ZF, Fei W, Wang M, Chiba H, Fan XL. A preliminary molecular phylogeny of the genus Scobura, with a synonym of Scobura masutaroi (Lepidoptera, Hesperiidae) ZooKeys. 2016;638:33–44. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.638.10026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.