Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequent malignant tumor of the eyelid; it progresses slowly and rarely metastasizes. However, BCC of the eyelid is partially invasive and can extend to the surrounding ocular adnexa even if appropriate treatment is performed. To understand the molecular mechanism underlying its pathogenesis, global gene expression analysis of surgical tissue samples of BCC of the eyelid (n=2) and normal human epidermal keratinocytes was performed using a GeneChip® system. The histopathological examination of surgically removed eyelid tissues showed the tumor nest composed with small basaloid. In the samples from patients 1 and 2, 687 and 713 genes were identified, respectively, demonstrating ≥5.0-fold higher expression than that noted in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. For the 640 genes with upregulated expression in both patient samples, Ingenuity® pathway analysis showed that the gene network in BCC of the eyelid included many BCC-associated genes, such as the following: BCL2 apoptosis regulator; Patched-1; and SRY-box 9. In addition, unique gene networks related to cancer cell growth, tumorigenesis, and cell survival were identified. These results of integrating microarray analyses provide further insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in BCC of the eyelid and may provide a therapeutic approach for this disease.

Keywords: basal cell carcinoma, microarray analysis, GeneChip system, Ingenuity pathway analysis, normal human epidermal keratinocytes

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequent malignant tumor of the eyelid, and it accounts for ~80% of all malignant eyelid tumors (1,2). Well-known risk factors of BCC include high levels of sunlight exposure and ultraviolet radiation and increasing age (2,3). The progression of BCC is relatively slow, and distant metastasis is rare (4–6). Various treatments have been reported for BCC of the eyelid, including surgical techniques, radiotherapy, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, laser ablation, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy (7). However, BCC is topically invasive tumor with destructive growth to surrounding tissue and has a recurrence rate of 1–10% even if appropriate treatment is performed (8). There is limited understanding of how alteration of gene expression in BCC of the eyelid is related to its pathogenesis; therefore, it is important to study the mechanism underlying carcinogenesis at the level of gene profiling.

Several studies have reported gene mutations associated with the carcinogenesis of BCC, such as mutations in the Patched-1 (PTCH1) gene of the sonic hedgehog (SHH) pathway (9) and mutations in the tumor suppressor p53 (10). PTCH-1 suppresses Smoothened signaling and plays an important role in the transcription of cell cycle regulators. p53 is a tumor suppressor gene and prevents gene replication in the case of DNA damage by cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. However, limited information is available at the genetic and molecular levels for BCC of the eyelid, and only a few gene profiling studies have been performed on this disease (11). Therefore, the aim of the current study was to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying BCC of the eyelid. For this purpose, we analyzed gene expression patterns by using a combination of global microarray analysis and bioinformatics tools.

Patients and methods

Patients and tissue samples

We enrolled two patients, patient 1 (78-year-old woman) and patient 2 (83-year-old woman) with BCC of the eyelid. The patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor at Toyama University Hospital. A part of the tissue samples was frozen and kept at −80°C after sampling for subsequent RNA extraction. The remaining part of the tissue samples was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and paraffin-embedded tissues were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Toyama (Toyama, Japan; no. 27–51), and the procedures conformed to the tenets of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients after they had been provided sufficient information about the procedures.

Cell culture

Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) were obtained from Kurabo Ind., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan; cat. no. KK-4109). They were cultured with HuMedia-KB2 medium (Kurabo Ind., Ltd.) at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted from cancer tissues and NHEKs using a NucleoSpin® RNA isolation kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co., Düren, Germany) along with On-column DNase I treatment, as per manufacturer instructions. RNA quality was analyzed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Microarray gene expression analysis

Microarray gene expression analysis was performed using a GeneChip® system with a Human Genome U133-plus 2.0 array, which was spotted with 54,675 probe sets (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The hybridization intensity data obtained were converted into a presence or an absence call for each gene, and changes in gene expression levels between experiments were detected by comparison analysis. The data were further analyzed using the GeneSpring® GX software (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) to extract the significant genes. For gene ontology analysis, including that pertaining to biological processes, cellular components, molecular functions, and gene networks, the data obtained were analyzed using Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis tools (Ingenuity Systems, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (12,13).

Results

Histopathological analysis

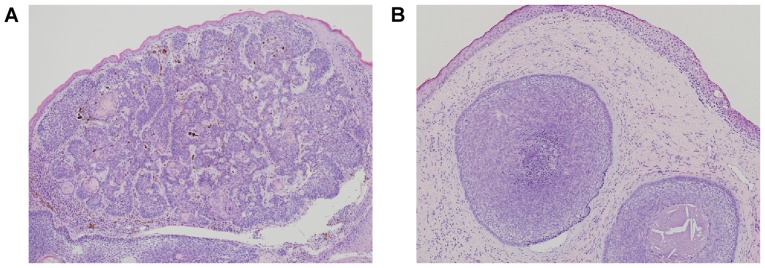

We performed histopathological examination of surgically removed eyelid tissues from two patients with a lower eyelid mass. We found that the tumor nest composed with small basaloid cell was proliferating with peripheral palisading and mucinous stroma; the histopathological findings were suggestive of BCC of the eyelid (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Histpathologic analysis of BCC of the eye. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of samples of BCC of the eyelid from patient 1 (A) and patient 2 (B) (original magnification, ×40). BCC, basal cell carcinoma.

Global gene expression analysis

Global gene expression analysis was performed to identify the genes involved in BCC of the eyelid. Complete lists of probe sets for all samples are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus, a public database (accession no. GSE103439). The GeneSpring software was used to analyze gene expression in the two patient samples and the NHEKs and revealed that many genes showed >5.0-fold difference in expression between the two sample types. The Venn diagram in Fig. 2 summarizes the numbers of specifically and commonly expressed genes in each group. The samples from patients 1 and 2 showed upregulation of the expression of 687 and 713 genes, respectively, as compared to that noted in the control cells (NHEKs); 640 genes were upregulated in both patient samples (Fig. 2). From these 640 genes, the upregulated genes that were reported to be associated with BCC are listed as follows: Nkyrin 2 (ANK2), anoctamin 5 (ANO5), androgen receptor (AR), ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit α 2 (ATP1A2), BCL2 apoptosis regulator (BCL2), calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit alpha2delta1 (CACNA2D1), complement factor H (CFH), chromogranin B (CHGB), cardiomyopathy associated 5 (CMYA5), collagen type VI α 3 chain (COL6A3), dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD), fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), filaggrin (FLG), forkhead box C1 (FOXC1), frizzled class receptor 7 (FZD7), heat shock protein family B member 2 (HSPB2), heat shock protein family B member 3 (HSPB3), heat shock protein family B member 7 (HSPB7), interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1), keratin 1 (KRT1), keratin 4 (KRT4), keratin 7 (KRT7), keratin 13 (KRT13), keratin 19 (KRT19), keratin 23 (KRT23), keratin 25 (KRT25), keratin 79 (KRT79), LIM homeobox 2 (LHX2), LIM and calponin homology domains 1 (LIMCH1), myosin heavy chain (MYH1), nebulin (NEB), nebulin related anchoring protein (NRAP), phosphodiesterase 4D interacting protein (PDE4DIP), PTCH1, SRY-box 9 (SOX9), tropomyosin 2 (TPM2), titin (TTN), tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP1) and xin actin binding repeat containing 2 (XIRP2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of genes that were differentially expressed in BCC of the eyelid (patients 1 and 2). Gene expression analysis was performed using a GeneChip® microarray system and the GeneSpring software. The numbers of upregulated genes are shown. In the samples from patients 1 and 2, we found that 687 and 713 genes, respectively, showed ≥5.0-fold higher expression that that noted in NHEKs. NHEK, normal human epidermal keratinocytes; BCC, basal cell carcinoma.

Identification of biological functions and gene networks

To identify the biological functions of and the relevant gene networks in the case of genes that were involved in BCC of the eyelid and showed differential expression, functional category and gene network analyses were conducted using the Ingenuity® Pathways Knowledge Base. In the case of the 640 genes that were upregulated in both patient samples, Ingenuity® pathway analysis showed that the gene network included many BCC-associated genes, such as the following (Fig. 3): AR; BCL2; PTCH1; CHGB; heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27); TPM2; NEB; XIRP2; TTN; CACNA2D1; CMYA5; MYH1; and SOX9.

Figure 3.

Networks involving upregulated genes in BCC of the eyelid. Upregulated genes were analyzed using Ingenuity pathway tools. The network is represented graphically with nodes (genes) and edges (biological associations between the nodes). Nodes and edges are displayed using various shapes and labels reflecting the functional class of each gene and the nature of the relationships involved, respectively. BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CHGB, chromogranin B; Hsp27, heat shock protein 27; TPM2, tropomyosin 2; NEB, nebulin; XIRP2, xin actin binding repeat containing 2; BCL2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; AR, androgen receptor; TTN, titin; CACNA2D1, calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit alpha2delta1; SOX9, SRY-box 9; PTCH1, Patched-1; MYH1, myosin heavy chain 1; CMYA5, cardiomyopathy associated 5.

We also identified unique gene networks related to cancer cell growth, tumorigenesis, and cell survival (Fig. 4). The cancer cell growth gene network included several genes, such as the following (Fig. 4A): AR, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3 (ERBB3), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), BCL2, insulin-like growth-factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP5), matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2), platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA), plasminogen activator, tissue type (PLAT), and prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA). This network was associated with the biological functions involved in cancer cell growth. The tumorigenesis gene network included several genes, such as the following: BCL2, KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT), CXCL12, serpin family F member 1 (SERPLNF1), insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), IGFBP5, PLAT, and neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (NTRK2). This network was associated with biological functions involved in tumorigenesis (Fig. 4B). The cell survival gene network included several genes, such as the following (Fig. 4C): AR; PSCA; PTCH1; IGF2; fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1); ERBB3; IGFBP5; versican (VCAN); BCL2; and galanin and GMAP prepropeptide (GAL). This network was associated with biological functions involved in cell survival.

Figure 4.

Gene networks. (A) Cancer growth, (B) tumorigenesis, and (C) cell survival in relation to the upregulated genes in patients with BCC of the eyelid. These networks were analyzed using the Ingenuity pathway analysis tools. The networks are represented graphically with nodes (genes) and edges (biological associations between the nodes). BCC, basal cell carcinoma; BCL2, BCL2 apoptosis regulator; MMP2, matrix metallopeptidase 2; PDGFRA, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α; CXCL12, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12; IGFBP5, insulin like growth factor binding protein 5; PLAT, plasminogen activator, tissue type; AR, androgen receptor; ERBB3, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3; PSCA, prostate stem cell antigen; GAL, galanin and GMAP prepropeptide; IGF2, insulin like growth factor 2; VCAN, versican; PTCH1, Patched-1; NTRK2, neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2; KIT, KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase.

Discussion

BCC of the eyelid is the most frequent malignant tumor of the eyelid; however, to date, only insufficient information is available regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying this disease. In the current study, we examined gene expression patterns associated with BCC of the eyelid by performing global microarray analysis, and gene network analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed using computational gene expression analysis tools.

We successfully identified a unique gene network on the basis of our data for upregulated gene expression in patients with BCC of the eyelid. This network included PTCH1 (14,15), which has been reported as an important player in BCC pathogenesis. The PTCH1 gene is a negative regulator of the SHH pathway; the dysfunction of this pathway has been recognized as essential events for BCC development (15,16). Furthermore, it is reported that PTCH-1 mutations contribute to the development of cutaneous eyelid BCC (17). In this network, PTCH1 was found to interact with several genes, such as MYH1, CACNA2D1, AR, SOX9, BCL2, CHGB, Hsp27, TPM2, NEB, NIRP2, TTN, and CMYA5. These genes have been reported to be related to BCC (18–20); it is possible that they play a role at the molecular level in the pathogenesis of BCC of the eyelid. Among them, SOX9 (21,22) and BCL2 (23,24) have been reported as biomarkers of BCC and may play an important role through interactions with PTCH1 in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Our functional category analysis showed that the upregulated genes in patients with BCC of the eyelid were related to biological functions such as cancer cell growth, tumorigenesis, and cell survival (Fig. 4). The cancer cell growth gene network consisted of nine genes, that is, AR (25), BCL2 (26), IGFBP5 (27), CXCL12 (28), ERBB3 (29), MMP2 (30), PDGFRA (31), PLAT (32) and PSCA (33), which have been found to be associated with the cell growth of various cancers, such as renal cell carcinoma, neuroblastoma and pancreatic cancer. The tumorigenesis gene network consisted of 10 genes, that is, PTCH1 (9,34), BCL2 (35), FGFR1 (36), AR (37), ERBB3 (38), IGF2 (39), IGFBP5 (40), PSCA (41), VCAN (42), and GAL (43), which have been reported to be associated with the tumorigenesis of various cancers, such as prostate cancer, neck squamous cell carcinoma and breast cancer. The cell survival gene network consisted of eight genes, that is, BCL2 (44), LGF2 (45), IGFBP5 (46), PLAT (47), NTRK2 (48), SERPINF1 (49), KIT (50), and CXCL12 (50), which have been found to be associated with cell survival in various cancers, such as lung cancer and prostate cancer. In BCC of the eyelid, the genes upregulated in these networks may play an important role in BCC cell survival through the network.

To summarize, from the 640 genes that were upregulated in both patient samples, Ingenuity® pathway analysis showed that the gene network of BCC of the eyelid included many BCC-associated genes, such as BCL2, PTCH1, and SOX9. We identified unique gene networks related with cancer cell growth, tumorigenesis, and cell survival. Thus, our results may help clarify the pathogenesis of BCC of the eyelid at the molecular level. However, the interaction between gene expression and this disease needs to be studied further. These results of integrating microarray analyses provide further insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in BCC of the eyelid and may lead to a therapeutic approach for this disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ANK2

ankyrin 2

- ANO5

anoctamin 5

- AR

androgen receptor

- ATP1A2

ATPase Na+/K+ transporting subunit α 2

- BCC

basal cell carcinoma

- BCL2

BCL2 apoptosis regulator

- CACNA2D1

calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit alpha2delta1

- CFH

complement factor H

- CHGB

chromogranin B

- CMYA5

cardiomyopathy associated 5

- COL6A3

collagen type VI α 3 chain

- CXCL12

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12

- DPYD

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

- ERBB3

erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3

- FGFR1

fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

- FLG

filaggrin

- FOXC1

forkhead box C1

- FZD7

frizzled class receptor 7

- GAL

galanin and GMAP prepropeptide

- Hsp27

heat shock protein 27

- HSPB2

heat shock protein family B member 2

- HSPB3

heat shock protein family B member 3

- HSPB7

heat shock protein family B member 7

- IFITM1

interferon induced transmembrane protein 1

- IGF2

insulin like growth factor 2

- IGFBP5

insulin like growth factor binding protein 5

- KIT

KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase

- KRT1

keratin 1

- KRT4

keratin 4

- KRT7

keratin 7

- KRT13

keratin 13

- KRT19

keratin 19

- KRT23

keratin 23

- KRT25

keratin 25

- KRT79

keratin 79

- LHX2

LIM homeobox 2

- LIMCH1

LIM and calponin homology domains 1

- MMP2

matrix metallopeptidase 2

- MYH1

myosin heavy chain 1

- NEB

nebulin

- NHEK

normal human epidermal keratinocytes

- NRAP

nebulin related anchoring protein

- NTRK2

neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- PDE4DIP

phosphodiesterase 4D interacting protein

- PDGFRA

platelet-derived growth factor receptor α

- PLAT

plasminogen activator, tissue type

- PSCA

prostate stem cell antigen

- PTCH1

Patched-1

- SERPINF1

serpin family F member 1

- SHH

sonic hedgehog

- SOX9

SRY-box 9

- TPM2

tropomyosin 2

- TTN

titin

- TYRP1

tyrosinase related protein 1

- VCAN

versican

- XIRP2

xin actin binding repeat containing 2

Funding

The present study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP16K20309).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

TY, YT and TH conceived the study, designed the experiments, wrote the manuscript and performed the experiments. SM and JI also performed experiments. TY and AH provided materials for microarray analysis and were involved in data analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Toyama (no. 27–51). All patients provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients after they were provided with sufficient information about the procedures and publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cook BE, Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:746–750. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allali J, D'Hermies F, Renard G. Basal cell carcinomas of the eyelids. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219:57–71. doi: 10.1159/000083263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neale RE, Davis M, Pandeya N, Whiteman DC, Green AC. Basal cell carcinoma on the trunk is associated with excessive sun exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindgren G, Lindblom B, Larkö O. Mohs' micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinomas on the eyelids and medial canthal area. II. Reconstruction and follow-up. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:430–436. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078004430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database, part II: Periocular basal cell carcinoma outcome at 5-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris DS, Elzaridi E, Clarke L, Dickinson AJ, Lawrence CM. Periocular basal cell carcinoma: 5-year outcome following Slow Mohs surgery with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections and delayed closure. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:474–476. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.141325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margo CE, Waltz K. Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular skin. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:169–192. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90100-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diepgen TL, Mahler V. The epidemiology of skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.146.s61.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Zwaan SE, Haass NK. Genetics of basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00579.x. quiz 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller PA, Vousden KH, Norman JC. p53 and its mutants in tumor cell migration and invasion. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:209–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heller ER, Gor A, Wang D, Hu Q, Lucchese A, Kanduc D, Katdare M, Liu S, Sinha AA. Molecular signatures of basal cell carcinoma susceptibility and pathogenesis: A genomic approach. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:583–596. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabuchi Y, Yunoki T, Hoshi N, Suzuki N, Kondo T. Genes and gene networks involved in sodium fluoride-elicited cell death accompanying endoplasmic reticulum stress in oral epithelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:8959–8978. doi: 10.3390/ijms15058959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yunoki T, Tabuchi Y, Hayashi A, Kondo T. Network analysis of genes involved in the enhancement of hyperthermia sensitivity by the knockdown of BAG3 in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:236–242. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Knobbe CB, Köhler B, Schönicke A, Scharwächter C, Kumar K, Blaschke B, Ruzicka T, Reifenberger G. Somatic mutations in the PTCH, SMOH, SUFUH and TP53 genes in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer CJ, Galan-Caridad JM, Weisberg SP, Lei L, Esquilin JM, Croft GF, Wainwright B, Canoll P, Owens DM, Reizis B. Zfx facilitates tumorigenesis caused by activation of the Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5914–5924. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupu M, Caruntu C, Ghita MA, Voiculescu V, Voiculescu S, Rosca AE, Caruntu A, Moraru L, Popa IM, Calenic B, et al. Gene expression and proteome analysis as sources of biomarkers in basal cell carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:9831237. doi: 10.1155/2016/9831237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celebi AR, Kiratli H, Soylemezoglu F. Evaluation of the ‘Hedgehog’ signaling pathways in squamous and basal cell carcinomas of the eyelids and conjunctiva. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:467–472. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astarci HM, Gurbuz GA, Sengul D, Hucumenoglu S, Kocer U, Ustun H. Significance of androgen receptor and CD10 expression in cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and trichoepithelioma. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:3466–3470. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharpe HJ, Pau G, Dijkgraaf GJ, Basset-Seguin N, Modrusan Z, Januario T, Tsui V, Durham AB, Dlugosz AA, Haverty PM, et al. Genomic analysis of smoothened inhibitor resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trautinger F, Kindas-Mügge I, Dekrout B, Knobler RM, Metze D. Expression of the 27-kDa heat shock protein in human epidermis and in epidermal neoplasms: An immunohistological study. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vidal VP, Ortonne N, Schedl A. SOX9 expression is a general marker of basal cell carcinoma and adnexal-related neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:373–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Youssef KK, Lapouge G, Bouvrée K, Rorive S, Brohée S, Appelstein O, Larsimont JC, Sukumaran V, Van de Sande B, Pucci D, et al. Adult interfollicular tumour-initiating cells are reprogrammed into an embryonic hair follicle progenitor-like fate during basal cell carcinoma initiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1282–1294. doi: 10.1038/ncb2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zbacnik AP, Rawal A, Lee B, Werling R, Knapp D, Mesa H. Cutaneous basal cell carcinosarcoma: Case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:903–910. doi: 10.1111/cup.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regl G, Kasper M, Schnidar H, Eichberger T, Neill GW, Philpott MP, Esterbauer H, Hauser-Kronberger C, Frischauf AM, Aberger F. Activation of the BCL2 promoter in response to Hedgehog/GLI signal transduction is predominantly mediated by GLI2. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7724–7731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He D, Li L, Zhu G, Liang L, Guan Z, Chang L, Chen Y, Yeh S, Chang C. ASC-J9 suppresses renal cell carcinoma progression by targeting an androgen receptor-dependent HIF2α/VEGF signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4420–4430. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannan S, Sutphin RM, Hall MG, Golfman LS, Fang W, Nolo RM, Akers LJ, Hammitt RA, McMurray JS, Kornblau SM, et al. Notch activation inhibits AML growth and survival: A potential therapeutic approach. J Exp Med. 2013;210:321–337. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanno B, Cesi V, Vitali R, Sesti F, Giuffrida ML, Mancini C, Calabretta B, Raschellà G. Silencing of endogenous IGFBP-5 by micro RNA interference affects proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:213–223. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton A, Friand V, Brulé-Donneger S, Chaigneau T, Ziol M, Sainte-Catherine O, Poiré A, Saffar L, Kraemer M, Vassy J, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1/chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 stimulates human hepatoma cell growth, migration, and invasion. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:21–33. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaborit N, Abdul-Hai A, Mancini M, Lindzen M, Lavi S, Leitner O, Mounier L, Chentouf M, Dunoyer S, Ghosh M, et al. Examination of HER3 targeting in cancer using monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:839–844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423645112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kesanakurti D, Chetty C, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Role of MMP-2 in the regulation of IL-6/Stat3 survival signaling via interaction with α5β1 integrin in glioma. Oncogene. 2013;32:327–340. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettazzoni P, Viale A, Shah P, Carugo A, Ying H, Wang H, Genovese G, Seth S, Minelli R, Green T, et al. Genetic events that limit the efficacy of MEK and RTK inhibitor therapies in a mouse model of KRAS-driven pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1091–1101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menouny M, Binoux M, Babajko S. Role of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 and its limited proteolysis in neuroblastoma cell proliferation: Modulation by transforming growth factor-beta and retinoic acid. Endocrinology. 1997;138:683–690. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.2.4919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saeki N, Gu J, Yoshida T, Wu X. Prostate stem cell antigen: A Jekyll and Hyde molecule? Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3533–3538. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Northcott PA, Jones DT, Kool M, Robinson GW, Gilbertson RJ, Cho YJ, Pomeroy SL, Korshunov A, Lichter P, Taylor MD, Pfister SM. Medulloblastomics: The end of the beginning. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:818–834. doi: 10.1038/nrc3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez-García I, Grütz G. Tumorigenic activity of the BCR-ABL oncogenes is mediated by BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5287–5291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall ME, Hinz TK, Kono SA, Singleton KR, Bichon B, Ware KE, Marek L, Frederick BA, Raben D, Heasley LE. Fibroblast growth factor receptors are components of autocrine signaling networks in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5016–5025. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroeder A, Herrmann A, Cherryholmes G, Kowolik C, Buettner R, Pal S, Yu H, Müller-Newen G, Jove R. Loss of androgen receptor expression promotes a stem-like cell phenotype in prostate cancer through STAT3 signaling. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1227–1237. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaught DB, Stanford JC, Young C, Hicks DJ, Wheeler F, Rinehart C, Sánchez V, Koland J, Muller WJ, Arteaga CL, Cook RS. HER3 is required for HER2-induced preneoplastic changes to the breast epithelium and tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2672–2682. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veronese A, Lupini L, Consiglio J, Visone R, Ferracin M, Fornari F, Zanesi N, Alder H, D'Elia G, Gramantieri L, et al. Oncogenic role of miR-483-3p at the IGF2/483 locus. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3140–3149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butt AJ, Dickson KA, McDougall F, Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29676–29685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chapman EJ, Kelly G, Knowles MA. Genes involved in differentiation, stem cell renewal, and tumorigenesis are modulated in telomerase-immortalized human urothelial cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1154–1168. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kunisada M, Yogianti F, Sakumi K, Ono R, Nakabeppu Y, Nishigori C. Increased expression of versican in the inflammatory response to UVB- and reactive oxygen species-induced skin tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:3056–3065. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tofighi R, Joseph B, Xia S, Xu ZQ, Hamberger B, Hökfelt T, Ceccatelli S. Galanin decreases proliferation of PC12 cells and induces apoptosis via its subtype 2 receptor (GalR2) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2717–2722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712300105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin Y, Fukuchi J, Hiipakka RA, Kokontis JM, Xiang J. Up-regulation of Bcl-2 is required for the progression of prostate cancer cells from an androgen-dependent to an androgen-independent growth stage. Cell Res. 2007;17:531–536. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linnerth NM, Baldwin M, Campbell C, Brown M, McGowan H, Moorehead RA. IGF-II induces CREB phosphorylation and cell survival in human lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:7310–7319. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashyap AS, Hollier BG, Manton KJ, Satyamoorthy K, Leavesley DI, Upton Z. Insulin-like growth factor-I:vitronectin complex-induced changes in gene expression effect breast cell survival and migration. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1388–1401. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin L, Jin Y, Hu K. Tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) promotes M1 macrophage survival through p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7910–7917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.599688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osborne JK, Larsen JE, Shields MD, Gonzales JX, Shames DS, Sato M, Kulkarni A, Wistuba II, Girard L, Minna JD, Cobb MH. NeuroD1 regulates survival and migration of neuroendocrine lung carcinomas via signaling molecules TrkB and NCAM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6524–6529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303932110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheikpranbabu S, Haribalaganesh R, Gurunathan S. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits advanced glycation end-products-induced cytotoxicity in retinal pericytes. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun J, Pedersen M, Rönnstrand L. The D816V mutation of c-Kit circumvents a requirement for Src family kinases in c-Kit signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11039–11047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808058200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.