Abstract

Objective:

Our objective is to describe the prevalence of breastfeeding and sleep location practices among US mothers and the factors associated with these behaviors, including advice received regarding these practices.

Methods:

A nationally representative sample of 3218 mothers, who spoke English or Spanish were enrolled at a sample of 32 US birth hospitals between January 2011 and March 2014.

Results:

Exclusive breastfeeding was reported by 30.5% of mothers, while an additional 29.5% reported partial breastfeeding. The majority of mothers, 65.5%, reported usually room sharing without bed sharing, while 20.7% reported bed sharing. Compared to mothers who room shared without bed sharing, mothers who bed shared were more likely to report exclusive breastfeeding (aOR 2.46: 95%CI 1.76, 3.45) or partial breastfeeding (aOR1.75: 95% CI 1.33, 2.31). The majority of mothers reported usually room sharing without bedsharing regardless of feeding practices, including 58.2% of exclusively breastfeeding mothers and 70.0% of non-breastfeeding mothers. Receiving advice regarding sleep location or breastfeeding increased adherence to recommendations in a dose response manner (the adjusted odds of roomsharing without bedsharing and exclusive breastfeeding increased as the relevant advice score increased), however, receiving advice regarding sleep location did not impact feeding practices.

Conclusion:

Many mothers have not adopted the recommended infant sleep location or feeding practices. Receiving advice from multiple sources appears to promote adherence in a dose response manner. Many women are able to both breastfeed and room share without bedsharing, and advice to adhere to both of these recommendations did not decrease breastfeeding rates.

What’s New:

Many mothers have not adopted recommended infant sleep location or feeding practices. This study suggests that receiving advice from multiple sources promotes adherence to these practices and providing advice on infant sleep recommendations did not negatively affect breastfeeding rates.

Keywords: SIDS, sleep location, breastfeeding, AAP safe sleep recommendations

Introduction

Infant sleep location (e.g. bed sharing and sleeping in a separate room) has been associated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and unintentional infant sleep-related death, leading the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to strongly recommend that infants sleep in the parents’ room, but in a separate sleep space.1 Increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates is also an important public health initiative, given the well-established beneficial health outcomes for both mothers and infants.2–5 Breastfeeding has been shown to be protective against SIDS, as well as certain infections that can increase the risk of SIDS.6 Promoting breastfeeding is a priority, and exclusive breastfeeding is recommended until the infant is 6 months old.2–5,7

There has been considerable debate among clinicians, researchers, and public health leaders over whether bedsharing is only a risk among impaired parents and whether advice to avoid bed sharing inadvertently interferes with breastfeeding.8–19 Parents may receive conflicting advice, resulting in confusion and possibly the adoption of even riskier behaviors, such as unplanned sleeping with infants on sofas, chairs or recliners.8,13,17,20

The Study of Attitudes and Factors Effecting Infant Care Practices (SAFE) is a nationally representative survey of mothers that examines advice received and behavior reported for a variety of infant care practices, including infant sleep location and breastfeeding. This report assesses the prevalence of breastfeeding and sleep location the factors that are associated with these behaviors, including advice received regarding these practices.

Methods

The SAFE Study used a stratified, two-stage, clustered design to obtain a nationally representative sample of mothers of infants, while oversampling Hispanic and non-Hispanic (NH) Black mothers. In the first stage, beginning in March 2010, we recruited 32 intrapartum hospitals with at least 100 births per year, based on American Hospital Association data. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all participating hospitals. In the second stage, January 2011 to March 2104, hospitals were assigned targets for sampling and enrollment of Hispanic, NH-Black, and non-Hispanic, non-Black (all other) race mothers. Recruitment periods were organized into three cycles in which each hospital obtained approximately one-third of its targeted enrollment, resulting in at least 250 completed surveys per cycle each from Hispanic and NH-Black mothers, for a total of 750 completed surveys for each group).

Mothers were eligible if they spoke English or Spanish, lived in the United States, and would be caring for their infant by 2–4 months after delivery. Mothers who were not expected to be caring for their baby at this age, such as due to infant’s prolonged hospitalization or social service placement, were excluded. Of 6,508 sampled mothers, 6,011 (92.4%) were eligible for the study. Of those eligible, 5,354 (89.1%) were approached during their postpartum stay, and of those, 3,983 (74.4%) agreed to participate and provided written informed consent. Mothers were asked to complete the follow-up survey, either online or by telephone, once their infant was at least 60 days old. The survey was completed by 3297 mothers, of whom 3218 mothers responded to the questions required for the study analyses (80.9 % of those enrolled). The survey development included extensive pilot testing and assessment of test-retest reliability.

Measures from follow-up survey

Infant Care Practices (Feeding, Sleep Location, Sleep Surface)

To assess infant care practices the relevant questions were:

Breastmilk or formula feeding: Over the LAST two weeks, what has your baby been drinking?

Responses were organized into three categories: Only Breastfeeding (only breastmilk, whether by breast or bottle), Partial Breastfeeding (included mostly breastmilk, equally breastmilk and formula, and mostly formula) or No Breastfeeding.

Sleep Location: Over the last two weeks, where has your baby USUALLY slept?

Responses were organized into three categories: the parents’ room, but in his or her own bed, designated as Room Sharing, Separate Room, or Bed Sharing Whole or Part of the night.

Sleep Surface: Please CHECK ALL the places your baby has slept, over the last two weeks.

Possible responses were: crib, bassinet, cradle, carry cot, pack and play, adult bed or mattress, sofa, car or infant seat, co-sleeper, or other.

Advice Received

To assess the advice received for both feeding and sleep location, mothers were asked if they received advice from each of the following four sources: my family, my baby’s doctor, the nurses at the hospital where my baby was born, and the media.

For sleep location, in order to evaluate the agreement with current AAP recommendations, only if the mother said they had received advice, she was then asked, “[Source of advice] thinks my baby should sleep in a parent’s (or other adult’s) room in his/her own bed,” and answered using a Likert scale from 1,”Strongly Disagree”, to 7, “Strongly Agree”. Responses of 5–7 were classified as the mother reporting the source advises room sharing without bed sharing, responses of 1–3 were classified as the mother reporting the source advises against room sharing without bed sharing, and responses of 4 were classified as “neutral”. Respondents were asked about all potential sleep locations, but for this analysis, we focused on room sharing without bed sharing.

For breastfeeding, if the answer was “yes”, the mother was asked, “[Source of advice] thinks I should breastfeed my baby.” and answered using a Likert scale from 1,”Strongly Disagree”, to 7, “Strongly Agree”. Responses of 5–7 were classified as the mother reporting that the source thinks she should breastfeed, responses of 1–3 were classified as the mother reporting that the source does not think she should breastfeed, and responses of 4 was classified as “neutral”.

An “advice score” for each infant care practice was calculated to sum advice received from all sources. For sleep location, each source the mother reported as advising room sharing without bed sharing received a +1, each source reported as disagreeing, received a −1, and each source reported as neutral or offering no advice received a 0. Therefore, the advice score could range from +4 (mother reports all four sources advise room sharing), to −4 (mother reports all four sources advise against room sharing). Similarly for breastfeeding, the advice score could range from +4 (mother reports all four sources think she should breastfeed), to −4 (mother reports all four sources do not think she should breastfeed). Due to few negative scores (7.2% of mothers for sleep location and 7.5% for breastfeeding advice), all negative scores were pooled into one category.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses accounted for the stratified two-stage cluster sample design for parameter estimates and standard errors, using SAS procedures for complex survey designs. Data were weighted to account for sampling probabilities and drop out, and to reflect the national joint distribution of maternal age and race/ethnicity. Generalized logit models were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between demographic factors (Table 1), infant care practices (Table 2), and advice received (Table 3) and each of three categories for feeding practices (only breastfeeding, partial breastfeeding, and no breastfeeding) and sleep locations (room sharing but not bed sharing, separate room, and bed sharing for all or part of the night). In these analyses, the primary analysis assessed the odds of the most adherent category vs. the least adherent category (i.e. only breastfeeding compared to no breastfeeding, and room sharing without bed sharing compared to bed sharing all or part of the night). As a secondary analysis, we also assessed the odds of the pooled “more adherent” categories to the least adherent category (i.e. only and partial breastfeeding compared to no breast feeding, and room sharing and sleeping in separate room compared to bedsharing all or part of the night). The results of these secondary analyses are provided in Tables 1-3, but are not discussed in the results section because results were similar to the primary analyses. All percentages presented are weighted, not raw, percentages.

Table 1:

Association between demographic factors and breastfeeding and bed sharing practices at follow-up.

| Characteristic | Overall N=3218 |

Weighted Percent a |

US Vital Statistics Percent a |

Breastfeed Only N=891 (30.5%) |

Breastfeed Partial N=977 (29.5%) |

Breastfeed None N=1350 (40.0%) |

Adj. OR (95%CI) Only vs. None |

Adj. OR (95%CI) Only/Partial vs. None |

Room share not bed sharing (RS not BS) N=2152 (65.5%) |

Separate room (SR) N=380 (13.7%) |

Bed Sharing whole or part of the night (BS) N=686 (20.7%) |

Adj. OR (95%CI) RS not BS vs. BS |

Adj. OR (95%CI) RS or SR not BS vs. BS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at survey | |||||||||||||

| 8–11 weeks | 1997 | 63.5% | NA | 35.4% | 27.9% | 36.7% | REF | REF | 65.6% | 13.2% | 21.3% | REF | REF |

| 12–15 weeks | 543 | 16.8% | NA | 26.3% | 33.6% | 40.1% | 0.78 (0.60,1.02) |

0.91 (0.73,1.14) |

66.9% | 11.4% | 21.7% | 1.04 (0.80,1.35) |

1.07 (0.84,1.37) |

| 16–19 weeks | 307 | 9.1% | NA | 19.2% | 26.7% | 54.1% | 0.53 (0.36,0.79) |

0.59 (0.45,0.79) |

62.4% | 18.6% | 18.9% | 1.14 (0.68,1.91) |

1.28 (0.78,2.11) |

| 20+ weeks | 371 | 10.6% | NA | 17.6% | 34.8% | 47.5% | 0.63 (0.43,0.91) |

0.90 (0.64,1.26) |

66.0% | 16.3% | 17.8% | 1.20 (0.80,1.78) |

1.32 (0.91,1.92) |

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 1646 | 50.8% | 48.8% | 27.9% | 31.6% | 40.5% | REF | REF | 64.7% | 13.7% | 21.5% | REF | REF |

| Female | 1568 | 49.2% | 51.2% | 33.2% | 27.4% | 39.4% | 1.18 (0.98,1.42) |

1.00 (0.86,1.16) |

66.4% | 13.6% | 20.0% | 1.10 (0.91,1.33) |

1.09 (0.91,1.29) |

| Birth weight | |||||||||||||

| <2500 | 193 | 5.5% | 8.0% | 17.5% | 30.3% | 52.1% | 0.41 (0.27,0.61) |

0.60 (0.41,0.88) |

70.8% | 10.7% | 18.5% | 1.27 (0.79,2.06) |

1.23 (0.76,1.99) |

| 2500+ | 3006 | 94.5% | 91.9% | 31.3% | 29.3% | 39.4% | REF | REF | 65.4% | 13.9% | 20.7% | REF | REF |

| Parity | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 1182 | 37.7% | 39.8% | 32.6% | 26.5% | 40.9% | REF | REF | 61.9% | 17.0% | 21.1% | REF | REF |

| 2 | 1072 | 33.8% | NA | 31.3% | 29.2% | 39.5% | 0.89 (0.68,1.16) |

0.95 (0.78,1.15) |

66.9% | 14.7% | 18.4% | 1.23 (0.94,1.59) |

1.18 (0.92,1.51) |

| 3+ | 955 | 28.5% | NA | 26.8% | 33.8% | 39.4% | 0.89 (0.68,1.16) |

0.99 (0.78,1.25) |

68.9% | 8.3% | 22.7% | 1.03 (0.78,1.36) |

0.94 (0.72,1.23) |

| Mother’s age | |||||||||||||

| Less than 20 | 264 | 7.4% | 8.1% | 13.8% | 23.9% | 62.2% | 0.62 (0.35,1.10) |

0.71 (0.49,1.03) |

64.3% | 7.6% | 28.0% | 0.73 (0.52,1.01) |

0.72 (0.53,0.98) |

| 20 to 29 | 1743 | 51.9% | 51.8% | 27.6% | 27.1% | 45.3% | REF | REF | 67.2% | 12.9% | 19.9% | REF | REF |

| 30 or more | 1211 | 40.7% | 40.1% | 37.2% | 33.6% | 29.2% | 1.31 (1.04,1.65) |

1.43 (1.14,1.79) |

63.6% | 15.8% | 20.5% | 0.93 (0.73,1.19) |

0.94 (0.74,1.20) |

| Race | |||||||||||||

| White | 1263 | 53.0% | 54.1% | 36.0% | 23.1% | 40.9% | REF | REF | 63.7% | 20.0% | 16.3% | REF | REF |

| Black | 803 | 12.8% | 14.7% | 14.4% | 32.9% | 52.6% | 0.67 (0.51,0.88) |

1.13 (0.83,1.56) |

68.4% | 7.1% | 24.5% | 0.61 (0.47,0.80) |

0.54 (0.42,0.69) |

| Hispanic | 876 | 25.4% | 23.1% | 27.3% | 38.7% | 34.0% | 1.56 (1.06,2.30) |

2.12 (1.46,3.07) |

69.8% | 4.7% | 25.5% | 0.84 (0.66,1.06) |

0.74 (0.59,0.94) |

| Other | 275 | 8.8% | NA | 30.0% | 36.8% | 33.2% | 0.75 (0.48,1.16) |

1.14 (0.81,1.60) |

60.2% | 11.5% | 28.3% | 0.71 (0.47,1.07) |

0.65 (0.42,1.02) |

| Mother’s Education | |||||||||||||

| Less than HS | 453 | 12.3% | 17.8% | 15.7% | 33.8% | 50.5% | REF | REF | 66.8% | 3.3% | 29.9% | REF | REF |

| HS or GED | 810 | 23.5% | 24.1% | 21.1% | 26.2% | 52.7% | 1.22 (0.79,1.87) |

1.04 (0.76,1.42) |

72.9% | 8.1% | 19.0% | 1.65 (1.16,2.36) |

1.68 (1.17,2.42) |

| Some college | 1016 | 30.8% | 28.8% | 24.8% | 29.1% | 46.1% | 1.35 (0.85,2.13) |

1.28 (0.92,1.77) |

65.5% | 13.6% | 20.9% | 1.32 (0.82,2.14) |

1.41 (0.88,2.27) |

| College or more | 926 | 33.4% | 28.0% | 47.8% | 31.0% | 21.3% | 4.18 (2.40,7.26) |

3.38 (2.15,5.33) |

60.0% | 21.3% | 18.8% | 1.42 (0.79,2.57) |

1.60 (0.90,2.85) |

| Household Income | |||||||||||||

| Less than $20K | 1114 | 29.1% | NA | 18.4% | 29.1% | 52.5% | REF | REF | 70.2% | 7.7% | 22.1% | REF | REF |

| $20K-49K | 814 | 24.6% | NA | 22.2% | 32.7% | 45.1% | 1.36 (0.99,1.88) |

1.28 (0.96,1.69) |

68.7% | 10.2% | 21.1% | 0.95 (0.72,1.25) |

0.96 (0.73,1.26) |

| $50K or more | 570 | 20.0% | NA | 38.3% | 27.0% | 34.7% | 1.76 (1.28,2.43) |

1.34 (1.02,1.77) |

64.1% | 15.4% | 20.6% | 0.79 (0.57,1.11) |

0.82 (0.58,1.15) |

| Unknown | 720 | 26.4% | NA | 45.6% | 28.9% | 25.5% | 2.12 (1.53,2.95) |

1.63 (1.24,2.14) |

58.6% | 22.3% | 19.1% | 0.81 (0.56,1.15) |

0.89 (0.62,1.26) |

| Region | |||||||||||||

| Northeast | 621 | 21.4% | 16.2% | 27.9% | 30.2% | 41.9% | 0.97 (0.50,1.88) |

1.02 (0.66,1.57) |

68.1% | 17.7% | 14.3% | 1.42 (0.90,2.24) |

1.45 (0.93,2.27) |

| Midwest | 487 | 12.9% | 21.1% | 35.0% | 25.6% | 39.4% | 1.40 (0.95,2.08) |

1.17 (0.85,1.61) |

66.0% | 21.5% | 12.5% | 1.52 (0.96,2.43) |

1.63 (1.01,2.63) |

| South/Southeast | 1344 | 41.2% | 38.1% | 23.5% | 30.1% | 46.4% | REF | REF | 66.8% | 12.3% | 20.9% | REF | REF |

| West | 766 | 24.5% | 24.6% | 42.1% | 29.9% | 28.0% | 2.43 (1.64,3.60) |

1.78 (1.20,2.63) |

61.0% | 8.5% | 30.5% | 0.61 (0.46,0.83) |

0.59 (0.44,0.79) |

The percentages presented in these columns represent column percentages and sum to 100 percent within each demographic category. All other percentages presented are weighted row percentages and sum to 100 percent across the 3 bed sharing or breastfeeding categories.

Adj. OR denotes adjusted odds ratio; CI denotes confidence interval; RS denotes room share; BS denotes bed sharing; SR denotes separate room

The odds ratios were adjusted for the following independent variables: geographic region, baby’s age and birth weight, parity, mother’s age, education, and race.

Table 2:

Associations between sleep location and feeding practices at follow-up.

| Characteristic | Overall N=3218 |

Weighted Percent a |

Breastfeed Only N=891 (30.5%) |

Breastfeed Partial N=977 (29.5%) |

Breastfeed None N=1350 (40.0%) |

Adj. OR (95%CI) Only vs. None |

Adj. OR (95%CI) Only/Partial vs. None |

Room share not bed sharing (RS not BS) N=2152 (65.5%) |

Separate room (SR) N=380 (13.7%) |

Bed sharing whole or part of the night (BS) N=686 (20.7%) |

Adj. OR (95%CI) RS not BS vs. BS |

Adj. OR (95%CI) RS or SR not BS vs. BS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual sleep location in past 2 weeks | ||||||||||||

| Room share without bed sharing |

2152 | 65.5% | 27.1% | 30.2% | 42.7% | REF | REF | |||||

| Separate room | 380 | 13.7% | 29.8% | 26.8% | 43.4% | 0.71 (0.49,1.02) |

0.74 (0.57,0.97) |

|||||

| Bed sharing whole or part of the night |

686 | 20.7% | 41.8% | 29.0% | 29.2% | 2.46 (1.76,3.45) |

1.75 (1.33,2.31) |

|||||

| Feeding practice in past 2 weeks | ||||||||||||

| Only breast milk | 891 | 30.5% | 58.2% | 13.4% | 28.5% | 0.41 (0.29,0.56) |

0.39 (0.28,0.54) |

|||||

| Partial breast milk | 977 | 29.5% | 67.2% | 12.5% | 20.4% | 0.75 (0.55,1.02) |

0.73 (0.54,0.99) |

|||||

| No breast milk | 1350 | 40.0% | 70.0% | 14.9% | 15.1% | REF | REF | |||||

| All sleep surfaces used in the past two weeks b | ||||||||||||

| Crib | 1772 | 55.2% | 25.9% | 33.2% | 40.9% | 0.71 (0.55,0.91) |

0.96 (0.78,1.19) |

63.4% | 23.0% | 13.6% | 2.12 (1.68,2.68) |

2.71 (2.19,3.36) |

| Adult bed/mattress | 1317 | 39.1% | 37.0% | 28.7% | 34.3% | 2.00 (1.49,2.69) |

1.49 (1.19,1.85) |

52.2% | 6.2% | 41.6% | 0.13 (0.10,0.17) |

0.12 (0.09,0.16) |

| Bassinet | 1180 | 38.1% | 33.5% | 25.6% | 40.9% | 1.12 (0.89,1.40) |

0.97 (0.81,1.15) |

75.1% | 7.1% | 17.8% | 1.53 (1.22,1.92) |

1.30 (1.04,1.63) |

| Car seat | 1059 | 36.1% | 39.7% | 27.7% | 32.5% | 1.45 (1.09,1.93) |

1.28 (1.02,1.62) |

62.0% | 17.1% | 20.9% | 0.83 (0.64,1.08) |

0.85 (0.66,1.08) |

| Pack and play | 1011 | 33.2% | 31.5% | 28.4% | 40.1% | 0.90 (0.76,1.07) |

0.95 (0.80,1.12) |

67.2% | 17.6% | 15.2% | 1.44 (1.14,1.83) |

1.45 (1.17,1.78) |

| Sofa | 318 | 10.2% | 35.1% | 25.8% | 39.1% | 1.15 (0.76,1.75) |

0.99 (0.75,1.32) |

57.6% | 9.0% | 33.4% | 0.49 (0.36,0.67) |

0.47 (0.35,0.63) |

| Cradle | 259 | 8.7% | 35.9% | 34.9% | 29.3% | 1.38 (0.87,2.18) |

1.45 (0.93,2.25) |

71.0% | 9.4% | 19.6% | 1.15 (0.82,1.61) |

1.05 (0.76,1.46) |

| Co-sleeper c | 238 | 8.0% | 45.2% | 30.1% | 24.7% | 1.80 (1.15,2.82) |

1.66 (1.06,2.60) |

51.5% | 3.3% | 45.2% | 0.29 (0.22,0.38) |

0.24 (0.18,0.32) |

The percentages presented in this column represent column percentages and sum to 100 percent within each practice category. All other percentages presented are weighted row percentages and sum to 100 percent across the 3 bed sharing or breastfeeding categories.

For each sleep surface, the odds ratios compare the use of the specific surface vs. not using the specified item.

Co-sleepers allow infants to sleep on separate surface that is adjacent to adult bed.

Adj. OR denotes adjusted odds ratio; CI denotes confidence interval; RS denotes room share; BS denotes bed sharing; SR denotes separate room.

The odds ratios were adjusted for the following independent variables: geographic region, baby’s age and birth weight, parity, mother’s age, education, and race.

Table 3:

Association between advice score categories and sleep location and feeding practices at follow-up.

| Characteristic | Overall N=3218 |

Weighted Percent a |

Breastfeed Only N=891 (30.5%) |

Breastfeed Partial N=977 (29.5%) |

Breastfeed None N=1350 (40.0%) |

Adj. OR (95%CI) Only vs. None |

Adj. OR (95%CI) Only/Partial vs. None |

Room share not bed sharing (RS not BS) N=2152 (65.5%) |

Separate room (SR) N=380 (13.7%) |

Bed sharing whole or part of the night (BS) N=686 (20.7%) |

Adj. OR (95%CI) RS not BS vs. BS |

Adj. OR (95%CI) RS or SR not BS vs. BS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sleep Location Advice Score b |

||||||||||||

| <0 | 210 | 7.2% | 27.6% | 32.9% | 39.5% | 0.91 (0.56,1.47) |

1.03 (0.67,1.59) |

29.9% | 47.0% | 23.1% | 0.54 (0.35,0.82) |

0.98 (0.65,1.49) |

| 0 | 972 | 31.6% | 31.3% | 29.2% | 39.5% | REF | REF | 59.3% | 18.0% | 22.6% | REF | REF |

| 1 | 679 | 22.6% | 33.6% | 27.7% | 38.7% | 1.18 (0.87,1.61) |

1.12 (0.89,1.42) |

68.2% | 10.3% | 21.5% | 1.20 (0.96,1.50) |

1.07 (0.86,1.33) |

| 2 | 553 | 17.1% | 34.9% | 26.1% | 39.0% | 1.35 (0.99,1.84) |

1.15 (0.90,1.47) |

71.6% | 8.9% | 19.4% | 1.39 (1.06,1.84) |

1.23 (0.94,1.62) |

| 3 | 417 | 11.7% | 24.6% | 30.5% | 44.9% | 1.07 (0.72,1.59) |

1.05 (0.77,1.42) |

76.8% | 3.5% | 19.7% | 1.63 (1.18,2.26) |

1.42 (1.02,1.97) |

| 4 | 387 | 9.8% | 21.9% | 36.9% | 41.2% | 1.25 (0.82,1.92) |

1.38 (0.98,1.95) |

81.7% | 3.6% | 14.7% | 2.36 (1.52,3.67) |

2.10 (1.35,3.25) |

| Feeding Advice Score b | ||||||||||||

| <0 | 230 | 7.5% | 8.2% | 15.4% | 76.5% | 0.31 (0.18,0.53) |

0.52 (0.32,0.87) |

72.6% | 13.7% | 13.6% | 1.52 (0.98,2.35) |

1.37 (0.87,2.15) |

| 0 | 360 | 11.6% | 21.0% | 15.3% | 63.7% | REF | REF | 62.0% | 20.9% | 17.1% | REF | REF |

| 1 | 412 | 13.4% | 31.5% | 23.3% | 45.1% | 1.94 (1.19,3.15) |

2.00 (1.41,2.84) |

61.7% | 13.9% | 24.3% | 0.74 (0.46,1.19) |

0.67 (0.44,1.04) |

| 2 | 605 | 19.9% | 30.0% | 28.9% | 41.1% | 2.24 (1.41,3.54) |

2.58 (1.82,3.65) |

65.4% | 14.3% | 20.3% | 0.93 (0.60,1.44) |

0.85 (0.55,1.32) |

| 3 | 772 | 23.1% | 37.5% | 33.3% | 29.2% | 4.46 (3.17,6.28) |

4.59 (3.51,6.00) |

64.8% | 11.8% | 23.4% | 0.91 (0.55,1.52) |

0.83 (0.50,1.37) |

| 4 | 839 | 24.6% | 35.0% | 40.8% | 24.2% | 5.67 (3.72,8.64) |

6.54 (4.69,9.10) |

67.9% | 11.5% | 20.6% | 1.12 (0.69,1.80) |

1.02 (0.64,1.62) |

The percentages presented in this column represent column percentages and sum to 100 percent within each advice score category. All other percentages presented are weighted row percentages and sum to 100 percent across the 3 bed sharing or breastfeeding categories.

The “advice score” is the sum of the advice received from all four sources (family, baby’s doctor, nurses, and the media). Each source that was reported as agreeing with the recommendation to room share without bed sharing received a +1, each source reported as disagreeing with that recommendation received a −1, and each source reported as providing neutral or no advice received a 0. Due to relatively few negative scores, all negative scores were pooled into one category. A score of 0 was obtained from mothers who received no advice from all four sources or who received conflicting advice from different sources resulting in a net score of 0.

Adj. OR denotes adjusted odds ratio; CI denotes confidence interval; RS denotes room share; BS denotes bed sharing; SR denotes separate room

The odds ratios were adjusted for the following independent variables: geographic region, baby’s age and birth weight, parity, mother’s age, education, and race.

Results

Study Population

The numbers and demographic characteristics for the mothers responding to the survey, along with the corresponding percentage, after statistical weighting, are provided in Table 1. The weighted percentages are similar to data reported for all US mothers giving birth in 2011–2012,21 (see Table 1). The weighted percentages of White, Black and Hispanic mothers were 53.0%, 12.8% and 25.4%, respectively, compared to 54.1%, 14.7% and 23.1% reported based on US vital statistics. For maternal education, weighted percentages were comparable to national data for high school graduates (23.5% weighted vs. 24.1% national) and women with some college (30.8% weighted vs. 28.8%% national), however, our sample somewhat underrepresented women with less than high school education (12.3% weighted vs. 17.8% national) and overrepresented college or more (33.4% weighted vs. 28.0% national). For categories of parity, maternal age, and percentage of infants born less than 2500 g, weighted percentages were within 3 percentage points of national percentages. The majority of infants, 63.5%, were 8–11 weeks, and all but 10.6% were less than 20 weeks of age, at the follow-up survey.

Prevalence of breastfeeding and sleep location practices

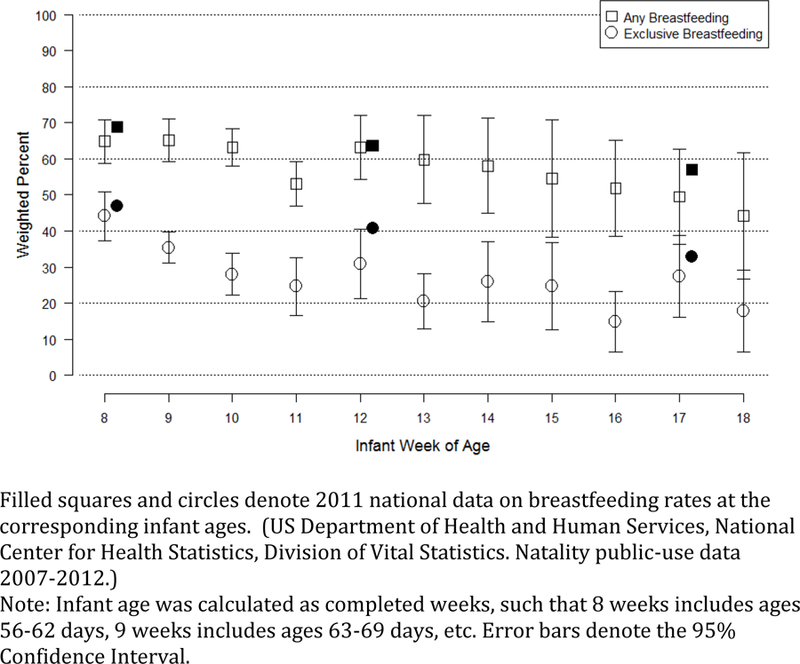

For breastfeeding, the weighted percentages of only (30.5%), some (29.5%) and no (40.0%) breastfeeding are shown in Table 1. Since breastfeeding is strongly associated with infant age, Figure 1 shows the percentages of exclusive and any (i.e. the sum of the only and partial breastfeeding categories) breastfeeding by infant age in weeks, as well as 2011 breastfeeding data reported by the CDC.21 Rates of any and only breastfeeding, as reported by the CDC at 60, 90, and 120 days of age, generally were within the 95% CI bounds for the SAFE data for the corresponding week of age.

Figure 1:

Weighted Percentage of Exclusive and Any Breastfeeding by Infant Age, 95% Confidence Interval

For sleep location, the majority of respondents, 65.5%, reported that their infants usually slept in the parents’ room, but in his or her own bed, designated as room sharing (Table 1), consistent with the AAP recommendations. Another 20.7% reported bed sharing for all or part of the night, and 13.7% reported that their infant slept in a separate room. Both of these practices are inconsistent with AAP recommendations.

Demographic factors associated with feeding and sleep location practices

The associations between demographic factors and breastfeeding and sleep location practices are provided in Table 1. For feeding practices, the factors associated with greater likelihood of only breastfeeding (vs. no breastfeeding) included younger infant age, normal birthweight, older maternal age, white and Hispanic race, higher level of maternal education, higher income and location in the West and Midwestern regions. Data for partial breastfeeding (vs. no breastfeeding) are consistent with observations for the only vs. no breastfeeding comparisons. For sleep location, factors associated with room sharing (vs. bedsharing for whole or part of the nights), included white race, mothers having at least a high school education.

Association between sleep locations, sleep surfaces and feeding practices

Associations between feeding practices, sleep location practices, and infant sleep surfaces are provided in Table 2. Compared to mothers who usually room shared, mothers who usually bed shared for all or part of the night were more likely to breastfeed (exclusive breastfeeding, aOR 2.46: 95%CI 1.76, 3.45; and partial breastfeeding, aOR 1.75: 95% CI 1.33, 2.31). Although not apparent in unadjusted analyses, adjusted odds of breastfeeding were lowest among mothers whose infants usually slept in a separate room. Compared to room sharing, the aORs were 0.71: 95% CI 0.49, 1.02; and 0.74: 95% CI 0.57, 0.97, for exclusive breastfeeding and partial breastfeeding, respectively, for those mothers whose infants slept in separate room. Despite the higher odds of breastfeeding among bed sharing mothers, the majority of mothers reported usually room sharing (without bedsharing), including 58.2% of exclusively breastfeeding mother and 70.0% of mothers reporting no breastfeeding. Of note, 15.1% of non-breastfeeding mothers indicated they bedshare for all or part of the night.

Table 2 also shows sleep surfaces used at least once during the prior two weeks and the corresponding associations with feeding and sleep location practices. The most commonly reported sleep surface was a crib (55%). Approximately one-third of mothers reported using each of the following: bassinet, pack and play, adult bed/mattress, and car seat. Of particular concern is that sofa, an especially dangerous sleep surface, was reported by 10.2% of mothers. Sofa sleeping was not associated with breastfeeding practice.

Advice on sleep location and feeding practices

The summary sleep location and feeding advice scores reported by mothers from doctors, nurses, family and media, are provided in Table 3. For sleep location, 31.6% had a neutral score of zero (primarily mothers reporting no advice from any source), while 61.2%, had an advice score of at least 1 and 38.6% had an advice score of at least 2, indicating that, overall, the sources of advice favored the AAP recommendation to room share without bed sharing. Similarly, for breastfeeding , 80.9% of mothers reported overall advice in favor of this practice. For both sleep location and feeding advice, a small proportion of respondents had a negative score, 7.2% and 7.5%, respectively.

Association between advice score and related practices

The association between the relevant advice score and the feeding and sleep location reported by mothers is shown in Table 3. After adjustment for geographic region, baby’s age and birth weight, parity, and mother’s age, education, and race, aORs for advice scores for both sleep location and feeding practices were consistent with a dose response, with the odds of roomsharing and exclusive breastfeeding increasing as the relevant advice score increased. For sleep location, compared to mothers with an advice score of 0, mothers whose advice score was negative had a lower adjusted odds of room sharing (vs. bedsharing all or part of the night), aOR 0.54 (95% CI 0.35–0.82), whereas mothers with scores of 1, 2, 3 and 4 had increasing aORs of 1.20 (95% CI 0.96–1.50), 1.39 (95% CI 1.06–1.84), 1.63 (95% CI 1.18–2.26) and 2.36 (95% CI 1.52–3.67). The results were similar when adjusted ORs were calculated for ANY non-bed sharing (i.e. either room sharing or in separate room) was compared to bed sharing all or part of the night.

For breastfeeding practices, the report of feeding advice also showed a strong dose response. Compared to mothers with an advice score of 0, mothers whose advice score was negative had a lower adjusted odds of exclusive breastfeeding (vs. no breastfeeding), a OR 0.31 (95% CI 0.18–0.53), whereas mothers with scores of 1, 2, 3 and 4 had increasing aORs of 1.94 (95% CI 1.19–3.15), 2.24 (95% CI 1.41–3.54), 4.46 (95% CI 3.17–6.28) and 5.67 (95% CI 3.72–8.64). The results were similar when adjusted ORs were calculated for ANY breastfeeding (i.e. either exclusive or partial breastfeeding) compared to no breastfeeding.

Association between advice score and unrelated practices

We also assessed the extent to which advice for one infant care practice, might impact on the other practice (Table 3). There was no suggestion that advice regarding sleep location was associated with breastfeeding practice or that advice regarding feeding practice was associated with sleep location. In each case, the adjusted ORs for the practices were all non-significant, close to 1.0 and showed no suggestion of a dose response related to the advice score.

Discussion

Using a representative sample of mothers in the US, our study reports sleep location and feeding practices, as well as factors associated with those practices. Adherence to recommended practice is reported by 65% of mothers for sleep location, and by only 30.5% of mothers for exclusive breastfeeding. After accounting for demographic factors, advice to have infant sleep in the parents’ room but in his or her own bed (room sharing) and advice to breastfeed both increased the likelihood of those practices with a strong dose response relationship; an indication that advice matters, and that advice from multiple sources appears cumulative. Consistent with prior studies, we also observed an association between breastfeeding and higher rates of bedsharing.14,22–24 However, roomsharing was the most common usual sleep location, even among mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding. In addition, there was no indication that providing advice to room share without bedsharing negatively affected the likelihood of breastfeeding. Although formula feeding is a well-established independent risk factor for SIDS while bed sharing,25,26 15% of non-breastfeeding mothers report bedsharing.

The rates of adherence to recommended practices observed in this study are generally consistent with previous reports.21,27 As shown in Figure 1, 2011 national breastfeeding rates reported by CDC are consistent with those in our study. Both the CDC and SAFE surveys rely on maternal self-report. However, the SAFE study used a two-week recall period, while the CDC survey asked mothers of infants aged 19 – 35 months when formula was first introduced and when breastfeeding stopped completely. These differences in recall period may explain any differences in results between the surveys.

Prior studies have documented relatively high rates of bed sharing, especially among Black mothers, and that advice to room share but not bed share is associated with increased rates of that recommended practice.28–31 Colson and co-workers, based on a national telephone survey, reported that in 2010 the overall rate of usual bedsharing was 13.5%, compared to 20.7% in the current study, and also reported that doctor advice not to bed share was associated with a decrease odds of bed sharing, which is consistent with our findings.27 Differences in bed sharing prevalence between these two studies are likely related to variation in the specific wording of the sleep location questions and under representation of Black and Hispanic mothers in the national telephone survey.27

Some have suggested that instructions to avoid bed sharing undermines the success of breastfeeding, which most would consider to be the recommended source of nutrition and the physiologic norm.14,32–34 Therefore, the prevalence of bed sharing may be partly attributed to advice given to bed share to enhance breastfeeding. Some suggest that babies and mothers who are breastfeeding and bed sharing sleep differently and may be more easily arousable, that bed sharing parents interact more with their infant during sleep and that breastfeeding mothers assume a posture that serves to prevent overlying when they are co-sleeping with their infant.32,33,35 Our data suggest that advice to avoid bed sharing is not associated with a decrease in breastfeeding, and shows that the majority of exclusively breastfeeding mothers report the recommended practice of room sharing without bed sharing.

There has also been a concern that advising against bed sharing might inadvertently lead to tired parents falling asleep with their infants in other dangerous locations, such as sofas or chairs.17 Sleeping with an infant on surfaces such as sofas, chairs or recliners, further increases the risk of SIDS associated with bed sharing and many infant deaths related to bed sharing are likely due to situations of accidental sleeping, when parents had not planned to bedshare.12,17,20 Kendall-Tackett et al found that up to 25% of a sample of primarily breastfeeding mothers fell asleep with their infants in unsafe sleep locations, such as chairs, sofas or recliners.20 We cannot directly address this issue, since we did not specifically ask mothers about instances of inadvertently falling asleep in various locations. However, our results do not suggest that following the recommendation for either sleep location or breastfeeding is associated with increased sofa sleeping. Sofa sleeping during the prior two weeks was reported by 10% of mothers and was equally distributed across the categories of feeding practice.

Limitations:

This study relies on maternal report of advice received and breastfeeding and infant sleep practices, and could be biased if mothers reported the behavior they thought was expected, rather than actual practices. It is possible that bed sharing families are less likely to tell their health care providers that their babies sleep with them.20 However, despite this potential reluctance to disclose, most studies of infant breastfeeding and sleep behavior, regardless of the conclusions regarding bed sharing, rely on parental report of those behaviors.18,22,36,37 Maternal recall of advice received 2–6 months prior may also be incomplete. Although 5354 mothers were approached for the study, 3983 enrolled and 3218 responded, we do not have detailed data about those who did not respond. We did not assess the specific reasons for maternal choices regarding bed sharing and breastfeeding. Our sample of 32 hospitals and more than 3200 mothers may not represent the US population precisely, however, the demographic characteristics of our weighted sample were reasonably well matched to nationally reported data.21

Conclusions:

Many mothers have not adopted the recommended infant sleep location or feeding practices. However, receiving advice from multiple sources can promote adherence in a dose response manner. Many mothers are able to breastfeed, exclusively or partially, when their infants sleep in the parents’ room, but in his or her own bed. Offering advice to adhere to both of these recommendations did not seem to negatively affect breastfeeding rates. A small, but important group of mothers report that their infants have slept on a sofa, a practice which is unrelated to their breastfeeding behavior. Given the substantial potential risk posed to infants by sleeping on sofas, chairs or other hazardous locations, health care providers and public health leaders should continue to specifically advise parents to avoid unplanned sleep in those locations, regardless of what feeding practice is chosen. In addition, the infants of the non-breastfeeding mothers who reported bed sharing could be at increased risk of sleep-related death.6,16,38

Our results provide information on the prevalence of infant sleep location and feeding practices and the influence of demographic factors and advice received on those practices, which can inform health care providers, public health leaders, and others who wish to prevent SIDS and other sleep-related deaths, and to promote breastfeeding. Given the cumulative impact of advice from different sources on sleep location and feeding, it would be important for pediatricians to promote a common understanding of relevant recommendations, among family members, nursing staff and the media, to ensure consistent messages from multiple sources.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant U10 HD059207.

The authors thank the study staff at the Boston University Slone Epidemiology Center for coordinating data collection from study sites and for all mother follow-up. The authors want to acknowledge Brenda Cox, PhD for hospital sampling and help with weighting. Lastly we want to thank the study staff at all 32 of the participating hospitals for their role in data collection and mother enrollment: Baylor University Medical Center, TX; Baystate Medical Center, MA; Ben Taub General Hospital, TX; Bethesda Memorial Hospital and Kidz Medical Services, FL; Brookdale Hospital and Medical Center, NY; CamdenClark Medical Center, WV; Delaware County Memorial Hospital, PA; Geisinger Regional Medical Center, PA; Genesys Regional Medical Center, MI; Hamilton Medical Center, GA; Jersey Shore University Medical Center, NJ; Johns Hopkins Hospital and Medical Center, MD; Kaweah Delta Health Care District, CA; Lake Charles Memorial Hospital, LA; Medical Center of Arlington, TX; Moreno Valley Community Hospital, CA; Mount Carmel, OH; Natchitoches Regional Medical Center, LA; Nashville General Hospital, TN; Northcrest Medical Center, TN; Riverside County Regional Medical Center, CA; Riverside Regional Medical Center, VA; Rush-Copley Medical Center, IL; Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center, CT; Saint Joseph Hospital, CA; Saint Mary’s Health Care, MI; Socorro General Hospital, NM; Sutter Roseville Medical Center, CA; Tacoma General Hospital, WA; Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Plano, TX; University of California, Davis Medical Center, CA; and Wheaton Franciscan Healthcare, WI.

Funding source: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant U10 HD059207. Michael J. Corwin, PI.

Abbreviations:

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- SIDS

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

- SAFE

Study of Attitudes and Factors Effecting Infant Care Practices

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: No conflict of interests to declare.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- 1.Task Force on Sudden Infant Death S, Moon RY SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 2011;128(5):1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Surgeon General (US) CfDCaPU, Office on Women’s Health (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding Rockville (MD) 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Services USDoHaH. Healthy People 2020 https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed February 5, 2015.

- 4.Section on B. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):e827–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007(153):1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hauck FR, Thompson JM, Tanabe KO, Moon RY, Vennemann MM. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011;128(1):103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. .The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding Rockville (MD) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, et al. Babies sleeping with parents: case-control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. CESDI SUDI research group. BMJ 1999;319(7223):1457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartick M Bed sharing with unimpaired parents is not an important risk for sudden infant death syndrome: to the editor. Pediatrics 2006;117(3):992–993; author reply 994–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eidelman AI, Gartner LM. Bed sharing with unimpaired parents is not an important risk for sudden infant death syndrome: to the editor. Pediatrics 2006;117(3):991–992; author reply 994–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming P, Blair P, McKenna J. New knowledge, new insights, and new recommendations. Arch Dis Child 2006;91(10):799–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Evason-Coombe C, Edmonds M, Heckstall-Smith EM, Fleming P. Hazardous cosleeping environments and risk factors amenable to change: case-control study of SIDS in south west England. BMJ 2009;339:b3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming P, Pease A, Blair P. Bed-sharing and unexpected infant deaths: what is the relationship? Paediatr Respir Rev 2015;16(1):62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna JJ, Mosko SS, Richard CA. Bedsharing promotes breastfeeding. Pediatrics 1997;100(2 Pt 1):214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol C. ABM clinical protocol #6: guideline on co-sleeping and breastfeeding. Revision, March 2008. Breastfeed Med 2008;3(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter R, McGarvey C, Mitchell EA, et al. Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case-control studies. BMJ Open 2013;3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartick M, Smith LJ. Speaking out on safe sleep: evidence-based infant sleep recommendations. Breastfeed Med 2014;9(9):417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Pease A, Fleming PJ. Bed-sharing in the absence of hazardous circumstances: is there a risk of sudden infant death syndrome? An analysis from two case-control studies conducted in the UK. PLoS One 2014;9(9):e107799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das RR, Sankar MJ, Agarwal R, Paul VK. Is “Bed Sharing” Beneficial and Safe during Infancy? A Systematic Review. Int J Pediatr 2014;2014:468538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall-Tackett KCZ, Hale TW Mother-Infant Sleep Locations and Nighttime Feeding Behavior: US Data from the Survey of Mothers’ Sleep and Fatigue. Clinical Lacation 2010;1(Fall):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS) CfDCaPC, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Division of Vital Statistics. Natality public-use data 2007–2012, on CDC Wonder Online Database November 2013; http://wonder.cdc.gov/natality-current.html, 2015.

- 22.Santos IS, Mota DM, Matijasevich A, Barros AJ, Barros FC. Bed-sharing at 3 months and breast-feeding at 1 year in southern Brazil. J Pediatr 2009;155(4):505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blair PS, Heron J, Fleming PJ. Relationship between bed sharing and breastfeeding: longitudinal, population-based analysis. Pediatrics 2010;126(5):e1119–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Hauck FR, Signore C, et al. Influence of bedsharing activity on breastfeeding duration among US mothers. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167(11):1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vennemann MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, et al. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics 2009;123(3):e406–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleming PJ, Blair PS. Making informed choices on co-sleeping with your baby. BMJ 2015;350:h563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colson ER, Willinger M, Rybin D, et al. Trends and factors associated with infant bed sharing, 1993–2010: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167(11):1032–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colson ER, Levenson S, Rybin D, et al. Barriers to following the supine sleep recommendation among mothers at four centers for the Women, Infants, and Children Program. Pediatrics 2006;118(2):e243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostfeld BM, Perl H, Esposito L, et al. Sleep environment, positional, lifestyle, and demographic characteristics associated with bed sharing in sudden infant death syndrome cases: a population-based study. Pediatrics 2006;118(5):2051–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu LY, Moon RY, Hauck FR. Bed sharing among black infants and sudden infant death syndrome: interactions with other known risk factors. Acad Pediatr 2010;10(6):376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenna JJ, Ball HL, Gettler LT. Mother-infant cosleeping, breastfeeding and sudden infant death syndrome: what biological anthropology has discovered about normal infant sleep and pediatric sleep medicine. Am J Phys Anthropol 2007;Suppl 45:133–161. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ball H Parent-infant bed-sharing behavior : Effects of feeding type and presence of father. Hum Nat 2006;17(3):301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breastfeeding AAoPSo. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):e827–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baddock SA, Galland BC, Bolton DP, Williams SM, Taylor BJ. Differences in infant and parent behaviors during routine bed sharing compared with cot sleeping in the home setting. Pediatrics 2006;117(5):1599–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krouse A, Craig J, Watson U, Matthews Z, Kolski G, Isola K. Bed-sharing influences, attitudes, and practices: implications for promoting safe infant sleep. J Child Health Care 2012;16(3):274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blair PS, Ball HL. The prevalence and characteristics associated with parent-infant bed-sharing in England. Arch Dis Child 2004;89(12):1106–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McVea KL, Turner PD, Peppler DK. The role of breastfeeding in sudden infant death syndrome. J Hum Lact 2000;16(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]