Abstract

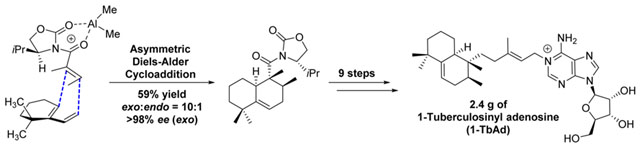

Despite its status as one of the world’s most prevalent and deadly bacterial pathogens, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection is not routinely diagnosed by rapid and highly reliable tests. A program to discover Mtb-specific biomarkers recently identified two natural compounds, 1-tuberculosinyl adenosine (1-TbAd) and N6-tuberculosinyl adenosine (N6-TbAd). Based on their association with virulence, the lack of similar compounds in nature, the presence of multiple stereocenters, and the need for abundant products to develop diagnostic tests, synthesis of these compounds was considered to be of high value but challenging. Here, a multigram-scale stereoselective synthesis of 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd is described. As a key-step, a chiral auxiliary-mediated Diels–Alder cycloaddition was developed, introducing the three stereocenters with a high exo endo ratio (10:1) and excellent enantioselectivity (>98% ee). This constitutes the first entry into the stereoselective synthesis of diterpenes with the halimane skeleton. Computational studies explain the observed stereochemical outcome.

Graphical Abstract

■ INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis is a bacterial infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Mtb is estimated to have infected 1.4 billion humans and is responsible for a mortality rate exceeding 1.5 million worldwide deaths annually.1 The persistence of Mtb in human hosts can be attributed to at least two key factors. First, intracellular survival of the bacterium is granted by successful infection of the endosomal network of phagocytes.2 In these phagocytes, Mtb arrests phagosomal acidification, which in turn inhibits pH-dependent killing mechanisms and other aspects of phagosome maturation. In its intracellular state, Mtb is protected from immunoglobulin and cellular immune responses during a decades long infection process. Second, its unusually hydrophobic, multilayered cell wall functions as an additional source of protection against drugs and immune response.3 In particular, the layers outside the cytosolic membrane are chemically diverse and quite different from lipids found in other cellular organisms. One catalog, organized by Lipid Maps criteria, defines more than 100 lipid subfamilies in Mtb, with more than 90% of these species expressed by actinobacteria and not by human cells or unrelated bacteria.4 Therefore, lipids can serve as specific chemical markers of mycobacteria.

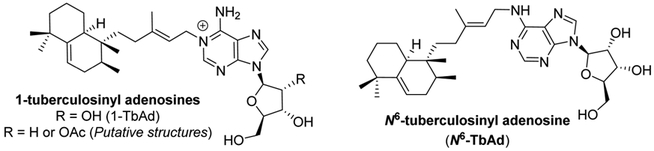

M. bovis strains known as Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) are genetically related to Mtb but are much less virulent and have been used as attenuated vaccinates in more than 1 billion humans worldwide.1 We reasoned that a comparative lipidomics screen to identify lipids present in Mtb, but absent in BCG, might identify virulence factors and Mtb-specific molecules useful for specific detection of this pathogen.5 By screening through more than 8000 compounds, this approach identified 1-tuberculosinyl adenosine (1-TbAd, Figure 1) as a previously unknown lipid, with no known substantially similar molecules in nature.6 Additional studies identified the pseudoisomer N6-tuberculosinyl adenosine (N6-TbAd, Figure 1), which was postulated to arise from an in vivo Dimroth rearrangement of 1-TbAd.7

Figure 1.

Tuberculosinyl adenosines from M. tuberculosis.

Very recently, two closely related compounds, tuber-culosinyl-2’-deoxyadenosine (“2’-deoxy 1-TbAd”) and tuber-culosinyl 2’-O-acetyladenosine (2’-acetyl TbAd, Figure 1), were discovered.8 The structures of these analogues were tentatively assigned based on mass spectrometry, confirming the existence of TbAd-like molecules in mycobacteria.

In a screen of bacteria or fungi, 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd were only found in Mtb and not in 13 BCG vaccine strains, environmental bacteria, or nonmycobacterial lung pathogens.7 These facts, along with their high rate of biosynthesis and ready shedding from the cell wall, make 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd attractive candidates for development as chemical markers for tuberculosis infection.9 Supporting this concept, 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd are produced in vivo in infected mice and are readily detected ex vivo in whole-lung homogenates and serum,7 as well as human serum,10 using a one-step RP-HPLC/MS method.

Further, TbAd biosynthesis requires the virulence-associated enzymes Rv3377c and Rv3378c, which were shown to be essential for phagosome maturation arrest.11 Therefore, 1-TbAd is expected to be involved in phagosomal survival of Mtb. Collectively, these studies provide two strong rationales, based on virulence and diagnostics, for a high yield stereoselective synthesis of 1-TbAd and N6-Tbad as reference factors and targets of ELISA technology. Here we report the first enantio-and diastereoselective total synthesis of 1-TbAd, together with its 13C-labeled congener, and N6-TbAd.

■ RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In 2010, the groups of Sorensen12 and Snider13 independently reported a synthesis of tuberculosinol.14 Both routes relied on a Diels–Alder reaction between 6,6-dimethyl-1-vinylcyclohexene 115 (Scheme 1) and a tigloyl-based dieneophile leading to the racemic core. This Diels–Alder reaction is as such very productive, as it forms the three stereocenters, of which one is quaternary, in the ring. The reaction, however, is also highly demanding as neither the diene nor the dienophile is very reactive, and the cycloaddition has to occur with exo selectivity. Whereas tiglic aldehyde generally gives a high endo selectivity (99:1),16 it is known from work by Danishefsky et al. that a bulky tiglic acid derivative leads to an increased exo selectivity.17 In the total synthesis of tuberculosinol by Sorensen et al., the Diels–Alder reaction was performed with the relatively small ethyl tiglate providing a modest diastereoselectivity of 2:1 in favor of the exo diastereomer.12 Increase of the steric bulk by using N-tigloyloxazolidinone in the Snider synthesis led to an exo:endoselectivity of ~10:1.13

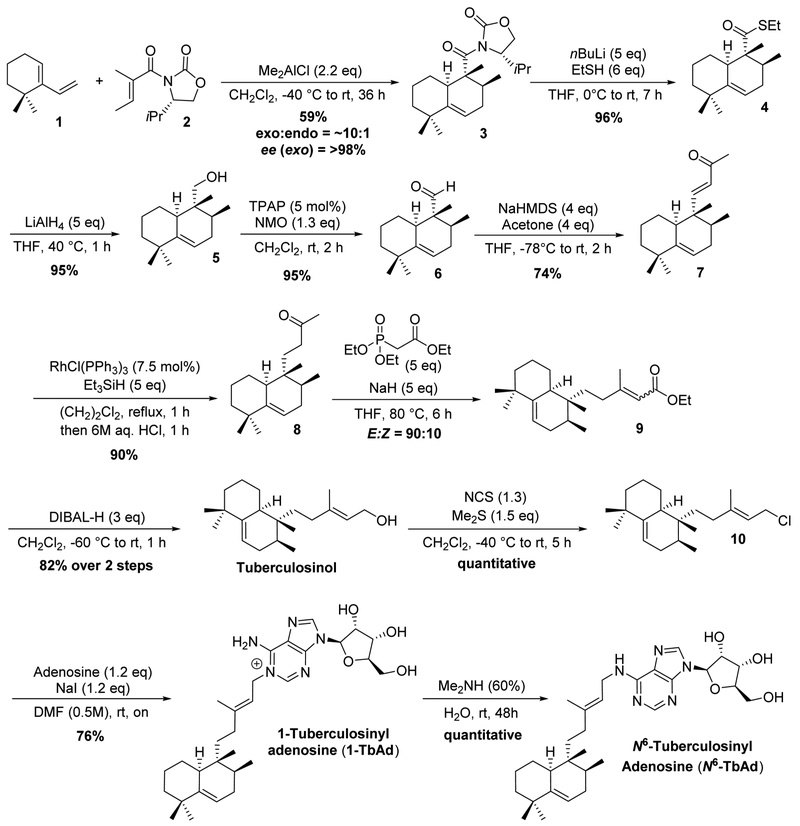

Scheme 1.

Asymmetric Total Synthesis of the Tuberculosinyl Adenosines, 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd

Although this (diastereoselective) Diels–Alder cycloaddition has been reported several times, an enantioselective version has not been developed.18 This, however, would provide a first and direct entry into the halimane family of diterpenes in an enantiopure fashion and, in particular, to the members of the TbAd-cluster. Extensive experimentation led to the conclusion that most asymmetric catalytic methods, and also the use of several chiral auxiliaries, were met with failure.19 Careful inspection of the assumed reaction coordinate, however, led to the hypothesis that an Evans-type chiral auxiliary could serve as an efficient reagent for chiral induction, as the substituent might shield one face of the dienophile. Snider et al. had shown that the parent (achiral) oxazolidinone, in combination with the strong Lewis acid Me2AlCl, produced a reactive dienophile.13 To our delight, upon reaction of diene 1 with (S)-isopropyl-N-tigloyloxazolidinone 220 and 2.2 equiv of Me2AlCl as the Lewis acid,21 the desired exo isomer 3 was formed in 59% yield and a diastereoselectivity of 10:1 (Scheme 1). Determination of the asymmetric induction was achieved by removal of the chiral auxiliary with lithium ethanethiolate followed by reduction of the resulting thioester 4 to the corresponding alcohol 5, in 91% over the two steps. Chiral HPLC analysis of 5 showed an excellent enantioselectivity for the exo isomer exceeding 98% ee. The minor diastereoisomer (endo) exhibited an ee of ~60%.

Remarkably, and despite the interest in tuberculosinol and related compounds, the absolute stereochemistry of tuberculosinol had not been unequivocally established. It was tentatively assigned22 by comparing the sign of the optical rotation of tuberculosinol with that of neopolypodatetraene A, which has the same bicyclic core structure, of known absolute configuration.23 This is not fully convincing since small differences in structure can lead to a different sign of optical rotation. In addition, tuberculosinol is formed by the geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate cyclase Rv3377c, whereas neo-polypodatetraene A is formed by a squalene cyclase. We therefore sought for a definite confirmation of the absolute stereochemistry.

Diels–Alder cycloadduct 3 turned out to be crystalline and its X-ray structure (see Supporting Information) established the absolute stereochemistry of tuberculosinol, based on the known stereocenter in the chiral auxiliary. The optical rotation of 5 () matched with that of the Sorensen laboratory (),12 obtained by chiral supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) of the racemate. Since alcohol 5 is obtained from 3 and the precursor of the naturally occurring enantiomer of tuberculosinol, the absolute stereochemistry corresponds to that in Scheme 1 (see Supporting Information for the X-ray structure).

The sequence from Diels–Alder adduct 3 to alcohol 5 was chosen to circumvent moderate yields (40–50%) in the direct removal of the chiral auxiliary with LiAlH4. NaBH4 was completely unreactive, presumably due to the significant steric crowding around the carbonyl functionality. This inaccessibility was observed once more upon attempts to reduce thioester 4 to aldehyde 6 with either DIBAL-H or a Fukuyama reduction (Pd/C, Et3SiH).24

With alcohol 5 in hand, the route was pursued along the lines of the Sorensen12 and Snider13 syntheses. A Ley–Griffith oxidation was performed on alcohol 5 to form aldehyde 6 which subsequently was condensed with acetone to furnish enone 7, in 70% yield over the two steps. The enone was then efficiently reduced by Wilkinson’s catalyst in combination with triethylsilane in 90% yield. Installation of the double bond was achieved by a Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons olefination with triethyl phosphonoacetate to produce the desired enoate 9 in a 9:1 E/Z mixture. This mixture was reduced with DIBAL-H, which after purification afforded pure, naturally occurring, tuberculosinol in 82% yield over the two steps.

To complete the synthesis of the tuberculosinyl adenosines, tuberculosinol was converted into tuberculosinyl chloride 10, using a Corey–Kim chlorination, in near quantitative yield.25 10 turned out to be unstable on silica, but purification was achieved by straightforward precipitation of the residual NCS and succinimide by the addition of pentane. A thorough study of the alkylation of adenosine with 10 led to a procedure involving NaI in DMF (0.5 M in 10).26 This produced 1-TbAd in 76% yield after purification. The compound was identical in all aspects to the natural isolate.

In addition to the synthesis of naturally occurring 1-TbAd, we also used this alkylation procedure to construct the derivatives (Z)-1-TbAd, 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd,8 and 13C-labeled 1-TbAd (see Supporting Information). The latter compound, made from adenosine fully 13C-labeled in the ribose, was prepared to facilitate the development of 1-TbAd as a biomarker for tuberculosis. Isotope-labeled biomarkers are important as standards for accurate quantification with HPLC-MS.

In order to verify its chemical structure as proposed by Lau et al.,8 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd was produced by reacting tuberculosinyl chloride with 2’-deoxy adenosine. CID/MS analysis of synthetic 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd produced MS spectra closely matching that of the proposed natural product. This, and the fact that 2’-deoxy adenosine is an abundant nucleoside, provides strong evidence that 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd is a M. tuberculosis produced natural product.

The finishing touch of our synthesis was the construction of N6-TbAd. It is known that 1-alkyl adenosines rearrange to N6-alkyl adenosines under nucleophilic conditions via a Dimroth rearrangement.27 Treatment of 1-TbAd with 60% aqueous Me2NH brought about this rearrangement to N6-TbAd quantitatively. This result concluded our total synthesis of the naturally occurring tuberculosinyl adenosines and directly confirmed the existence of a plausible, nonenzymatic basis for generation of the N6-product from 1-TbAd, as hypothesized previously.7

The excellent stereoinduction observed in the Diels–Alder reaction deserves particular attention. In 2010 the Snider laboratory used the achiral tigloyl-based oxazolidinone and stated “The unsubstituted oxazolidinone was chosen to minimize steric interactions between the α-methyl group and the oxazolidinone and because asymmetric induction seemed unlikely in an exo Diels–Alder reaction in which a chiral oxazolidinone would be far away from the diene (1)”.13

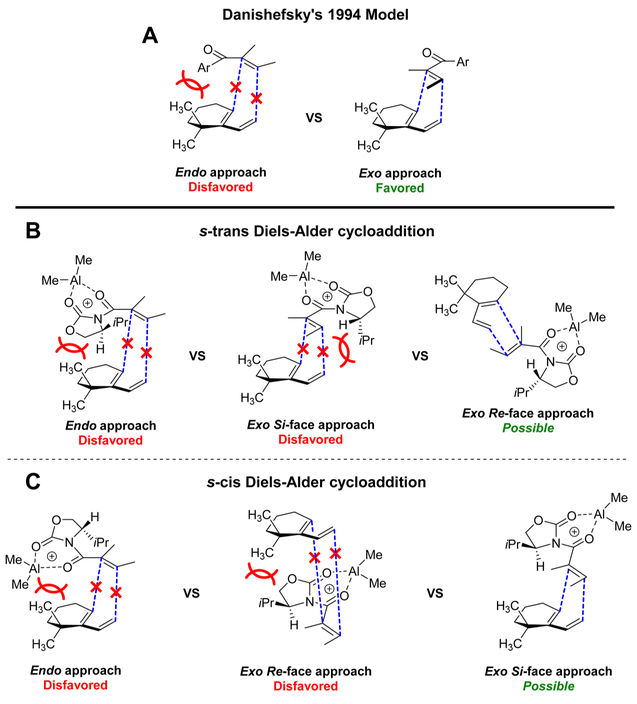

This statement was based on the mechanistic model proposed by Danishefsky (Figure 2A), explaining exo-selectivity in the Diels–Alder reaction with diene 1.17 A steric clash between the diene’s geminal dimethyl group and the bulky dienophile disfavors the endo approach, hence providing the exo-Diels–Alder adduct selectively. This model, however, only addresses the dienophile in its s-trans conformation. Although this model predicts the observed exo-selectivity, it ignores a possible contribution of the s-cis conformation of the dienophile.28

Figure 2.

Models for stereoinduction in the Diels–Alder cycloaddition between diene 1 and dienophile 2.

In a combined experimental and computational study by Houk, Gouverneur et al., it was shown that Evans chiral auxiliary-based dienophiles provide efficient chiral induction and endo or exo-selectivity depending on the substitution at the α-position of the dienophile and the diene.29 The reaction takes place from the s-cis conformation of the dienophile as expected, as the diene is not substituted at the α-position, like in the current tigloyl-based dieneophile.

In Figure 2B, a model for the [4 + 2] cycloaddition between diene 1 and dienophile 2, in its s-trans conformation, is presented. As in Danishefsky’s model,17 the endo approach is disfavored for reasons previously mentioned. The exo approach on the Si-face of the dienophile seems disfavored as the isopropyl group on the chiral oxazolidinone clashes with the vinyl substituent of the diene. The Re-face approach, on the other hand, seems plausible as no obvious steric interactions shield this face from reaction. However, this facial approach would provide the Diels–Alder adduct 3 with a stereochemistry opposite to that observed experimentally.

Considering the s-cis conformer of dienophile 2 (Figure 2C), the endo approach is again disfavored, this time because of a clash between the dimethylaluminum function and the geminal dimethyl. The Re-face appears unapproachable due to a steric interaction between the isopropyl group and the geminal dimethyl in diene 1. A Si-face approach does not result in such steric clash and provides Diels–Alder adduct 3 with the experimentally obtained stereochemistry. This model therefore seems to be a better picture of the course of the reaction, despite the expectation that the s-cis conformation of the dienophile is unfavorable compared to the s-trans conformation. Therefore, we studied the reaction through DFT calculations.

Calculations were carried out using the ADF program suite30 at the BP8631/TZ2P level of theory. The geometries of all stationary points were optimized in the gas phase and verified to be proper local minima or transition states through vibrational analyses. The gas-phase harmonic frequencies were used for the enthalpic and entropic corrections to the free energies at 233.15 K (−40 °C).

First, it was determined whether the s-cis conformer is energetically feasible by calculating the s-trans/s-cis equilibrium for Me2Al-complexed dienophile 2. We found the s-trans conformer is favored over the s-cis conformer by 0.2 kcal/mol on the Gibbs free energy surface at 233.15 K, providing a ratio of 6:4 respectively at −40 °C (Figure 3). With a rotational barrier of ΔG‡ = 3.2 kcal/mol, however, the conformers are readily interconvertible, and due to the Curtin–Hammet principle, the observed product can be reached via the s-cis conformer.32

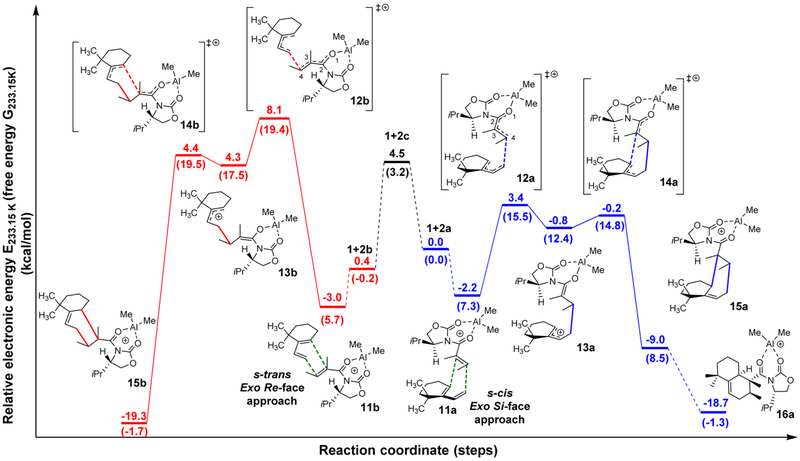

Figure 3.

DFT BP86/TZ2P calculated reaction coordinate for the Diels–Alder cycloaddition between diene 1 and dienophile 2. For these studies, the s-cis exo Si-face approach was chosen as the reference point. IRC analyses were performed on both transition states on the s-cis pathway (blue lines) and are connected with solid lines. The dashed lines connect the structures in which IRC was not performed, but was found to exist on the potential energy surface. (Relative electronic energies are given in kcal/mol, and relative Gibbs free energies are given in kcal/mol in parentheses.) The geometry of diene 1, aluminum-complexed s-cis conformer of the dienophile (2a), aluminum-complexed s-trans conformer of the dienophile (2b), and the transition state between 2a and 2b corresponding to the rotation along the C(2)–C(3) bond (2c) were optimized separately. The energies of the three states 1 + 2a, 1 + 2b and 1 + 2c are the sum of the corresponding diene and aluminum-complexed dienophile fragments (See Supporting Information).

The energy profile for the entire reaction pathway was calculated next. On this basis, and according to the models in Figure 2, the endo approach for both the s-trans and s-cis conformers can be ruled out. Attack of the s-trans conformer from the exo Si-face and attack of the s-cis conformer from the exo Re-face are prohibited too, as modeling showed significant steric clash for initial bond formation (see Supporting Information). The two models in which calculations were carried out were the Re-face and the Si-face approaches for the s-trans and s-cis conformers, respectively (both exo attack).

The reaction of the s-trans conformer (Figure 3, red pathway) has a considerably higher activation energy (ΔG‡ = 19.4 kcal/mol) for the initial and enantio-determining step, compared to the reaction of the s-cis conformer (blue path, ΔG‡ = 15.5 kcal/mol). This convincingly explains the reaction outcome.

The Diels–Alder reaction was found to proceed stepwise rather than concerted. After the first bond formation, the cationic intermediate is in an energy well with a relative energy of 12.4 kcal/mol, before proceeding to form the second bond with a saddle point at 14.8 kcal/mol. From this point the reaction is thermodynamically downhill to form the Me2Al complexed Diels–Alder adduct 3 with a relative ΔG = −1.3 kcal/mol.

The differences in activation energies between the two pathways can be rationalized using the activation strain model.33 In this model, the electronic activation energy (ΔE‡) is the sum of strain energy (ΔEstrain‡), which is associated with the deformation of the starting materials to the geometry they acquire in the transition state, and the interaction energy (ΔEint‡), which is associated with the favorable electronic interactions between the deformed starting materials.i.e., ΔE‡ = ΔEstrain‡ + ΔEint‡.

As outlined in Table 1, the difference in ΔE‡ between transition states 12a and 12b is mainly due to strain, not due to orbital interaction. Upon inspection of the geometry of the dienophile at the transition state, the dihedral angle O(1)–C(2)–C(3)–C(4) is deviating 17.2° and 18.2° from planarity for transition states 12a and 12b, respectively, while the corresponding dihedral angle of the s-cis and s-trans conformers are deviating 29.8° and 43.0° from planarity, respectively.

Table 1.

Activation Strain Analysis (in kcal/mol) for the Four Transition States Shown in Figure 3

| transition states | ΔE‡ | ΔEstrain‡ | ΔEint‡ | ΔH‡ | TΔS‡ | ΔG‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12a | 3.4 | 16.5 | −13.1 | 4.2 | −11.4 | 15.6 |

| 12b | 7.7 | 23.4 | −15.7 | 8.4 | −11.3 | 19.7 |

| 14a | −0.2 | 79.1 | −79.3 | 2.2 | −12.6 | 14.8 |

| 14b | 3.9 | 75.6 | −71.6 | 5.8 | −13.9 | 19.7 |

The larger deviation from planarity, of the dihedral angle O(1)–C(2)–C(3)–C(4), in the s-trans conformer might be attributed to a steric interaction between the hydrogen atom at the stereocenter of the oxazolidinone scaffold and that of the hydrogen atom at C(4). The distance between these two hydrogen atoms is 2.07 Å for the s-trans conformer, while the closest distance between the hydrogen atom at the oxazolidinone and the hydrogens on the α-methyl group in the s-cis conformer is 2.17 Å. Since both distances are less than the sum of the van der Waals radii of two hydrogen atoms (2.4 Å), the steric interactions between the hydrogen atoms in both cases are non-negligible, and the steric interaction in the s-cis conformer is indeed less severe than that in the s-trans conformer. The s-cis conformer can thus retain a relatively planar geometry without experiencing severe steric interactions. The larger difference of the dihedral angle between the ground state and the transition state of the s-trans conformer compared to that of the s-cis conformer could explain the difference in activation strain.

While ΔEint‡ plays a larger role in determining the ΔE‡ of the second transition state, this difference is argued to be less important due to the fact that enantioselectivity is determined at the first transition state.

This computational study shines light on the stereochemical course of Diels–Alder reactions with tigloyl (i.e., α,β-disubstituted) chiral oxazolidinones. Although the Curtin–Hammet principle in Diels–Alder reactions has been described before,28 in the use of tigloyl-based dienophiles, this concept is novel.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, 1-TbAd and N6-TbAd have been prepared as pure stereoisomers in 10 and 11 steps, respectively, starting from diene 1. Installation of the three chiral centers in tuberculosinol was efficiently achieved (exo:endo = 10:1, >98% ee for the exo isomer) employing a chiral auxiliary-aided Diels–Alder reaction. The synthesis has been scaled to produce 2.4 g of 1-TbAd in 21% overall yield. In addition, the family members N6-TbAd and 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd have been prepared, confirming the structure of the latter. The compounds are currently studied as biomarkers for tuberculosis, which is assisted by the availability of 13C-labeled 1-TbAd.

The stereoselectivity observed in the Diels–Alder reaction was also investigated in detail. In silico studies showed the cycloaddition proceeded via the thermodynamically less stable s-cis conformer of the dienophile because this conformer needs less deformation in the transition state, which results in a lower reaction barrier.

This asymmetric and exo-selective Diels–Alder reaction sets the stage for the synthesis of other diterpenes bearing the halimane skeleton as present in tuberculosinol (i.e., akaterpin,34 siphonodictyal D,35 neopolypodatetraene A,23 cacospongionolide F,36 11R*-acetoxyhalima-5,13E-dien-15-oic acid,37 and mamanuthaquinone38).

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

6,6-Dimethyl-1-vinylcyclohex-1-ene (1)15.

To a solution of cyclohexanone (9.91 mL, 96 mmol) and iodomethane (12.5 mL, 201 mmol, 2.05 equiv) in dry THF (500 mL), cooled to −20 °C, was added dropwise, using a dropping funnel, a solution of KOtBu (22.6 g, 201 mmol, 2.05 equiv) in dry THF (125 mL). Upon addition, a white precipitate formed, and the reaction turned yellow. After addition, the mixture was stirred for 60 min at this temperature after which GC/MS indicated complete conversion of the cyclohexanone. The reaction mixture was quenched with an aqueous saturated NH4Cl solution (200 mL). Quenching resulted in significant, but not complete, disappearance of the white precipitate, which was completely removed by filtration of the quenched mixture over a glass filter. The phases were separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with ether. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash column chromatography of the resulting oil using pentane:ether (4:1) afforded 2,2-dimethylcyclohexanone (18.3 g, 145 mmol, 49% yield) ~90% pure. Note: The reaction was performed 3× on this scale. The extractions were performed on the combined reaction mixtures. The yield represents that of the combined reactions. In order to obtain the desired 90% purity, the individual column fractions were analyzed with GC/MS.

To a stirred solution of vinylmagnesium bromide (174 mL, 174 mmol, 1.2 equiv) at 0 °C was added dropwise a solution of 2,2-dimethylcyclohexanone (18.3 g, 145 mmol) in dry THF (50 mL) over 30 min. The reaction was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was carefully quenched with an aqueous saturated NH4Cl solution (75 mL). After phase separation, the aqueous layer was extracted with ether (3 × 25 mL). The organic layers were combined and dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting yellowish oil (27.3 g, > 99% yield) was used in the subsequent dehydration reaction.

The crude alcohol was dissolved in benzene (300 mL). To the stirred solution, anhydrous CuSO4 (50 g, 313 mmol, 2.2 equiv) was added. The suspension was refluxed under Dean–Stark conditions overnight. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt and thereafter filtered over Celite and flushed with pentane. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residual oil was subjected to flash column chromatography employing pentane as the eluent. Pure 6,6-dimethyl-1-vinylcyclohex-1-ene 1 (10.5 g, 77 mmol, 53% yield) was obtained as a colorless oil.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.32 (dd, J = 17.2, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (t, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1H), 4.92 (d, J = 10.9 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (q, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 1.61 (dt, J = 12.0, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 1.53–1.46 (m, 2H), 1.07 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.7, 137.2, 123.2, 112.8, 39.6, 33.3, 28.5, 26.3, 19.3.

Note: Diene 1 is rather volatile, and therefore concentration, after column chromatography, was performed very carefully. As a result the NMR spectra of diene 1 contain benzene and traces of pentane.

(S,E)-4-Isopropyl-3-(2-methylbut-2-enoyl)oxazolidin-2-one(2)20.

To vigorously stirred thionyl chloride (27.2 mL, 375 mmol, 1.5 equiv) in a 250 mL three-neck round-bottom flask (open flask!) was added portionwise (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoic acid (25 g, 250 mmol). Each portion was added after significant gas evolution (HCl, SO2) ceased. After addition of all the acid, the reaction mixture (open flask!) was heated to 40 °C until no gas evolution was observed. The three-neck round-bottom flask was equipped with a reflux condenser, and the reaction was refluxed for 1 h. After this time, no gas evolution was observed. The excess of thionyl chloride was removed by concentration under reduced pressure. The product was subsequently distilled in the rotavapor to afford (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoyl chloride E (29.6 g, 250 mmol, quantitative) as a clear liquid. Note: The reaction is exothermic with vigorous evolution of HCl/SO2 gas.

To a cooled solution, −60 °C, of (S)-4-isopropyloxazolidin-2-one (25.0 g, 194 mmol) in dry THF (500 mL) was added dropwise n-butyllithium (133 mL in hexanes, 213 mmol, 1.1 equiv) by the aid of a dropping funnel. Upon addition, the reaction mixture became turbid. After addition, the reaction was allowed to warm-up to 0 °C and was stirred at this temperature for 30 min, where after the mixture was recooled to −60 °C and (E)-2-methylbut-2-enoyl chloride (29.6 g, 250 mmol, 1.3 equiv) was added dropwise by the aid of a syringe pump over 20 min. Upon addition the reaction mixture turned yellow/orange. After addition of the acid chloride, the reaction was allowed to warm up to rt, and the reaction became transparent. The reaction was stirred overnight after it was carefully quenched using aqueous HCl (1 M, 150 mL). After phase separation, the aqueous layer was extracted twice with ether. The combined organic layers were washed with a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 and dried using Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. A solid formed which was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) and subjected to flash column chromatography employing pentane:ether (3:2) as the eluent to afford pure (S,E)-4-isopropyl-3-(2-methylbut-2-enoyl)oxazolidin-2-one 2 (25 g, 118 mmol, 61% yield) as a waxy solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.20 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (dt, J = 9.0, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (t, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (dd, J = 8.9, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (dq, J = 13.8, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 1.90 (s, 3H), 1.80 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.91 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.9, 153.8, 134.7, 131.9, 63.5, 58.4, 28.4, 18.0, 15.1, 14.2, 13.5. HRMS: (ESI +) calculated mass [M + H]+ C11H18NO3+ = 212.1281, found: 212.1281. Calculated mass [M + Na] + C11H17NO3Na+ = 234.1101 found: 234.1101.

(S)-4-isopropyl-3-((1 R,2S, 8aR)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene-1-carbonyl)oxazolidin-2-one (3).

To a stirred solution of dienophile 2 (9.13 g, 43.2 mmol, 1.1 equiv) in dry (CH2)2Cl2 (250 mL) at −40 °C under N2 was added Me2AlCl (86.5 mL, 1 M in hexanes, 86.5 mmol, 2.2 equiv) over 15 min, by the aid of a dropping funnel. The yellow reaction mixture was stirred for 20 min, and diene 1 (5.35 g, 39.3 mmol) in dry (CH2)2Cl2 (90 mL) was added dropwise over 15 min by the aid of a dropping funnel. The reaction was then allowed to warm to rt and was stirred for 36 h at this temperature. GC/MS indicated complete conversion of the diene.

The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C and carefully quenched by dropwise addition of aqueous 1 M HCl (50 mL). After phase separation, the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash column chromatography with pentane:ether (6:1) provided (S)-4-isopropyl-3-((1R,2S,8aR)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene-1-carbonyl)-oxazolidin-2-one 3 as a white crystalline solid (8.0 g, 19.6 mmol, 59% yield, exo:endo = 10:1). Note: the reaction temperature was monitored inside the flask. Lower temperatures leads to crystallization of the dienophile.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.47 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.33–4.13 (m, 2H), 3.34 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 3.15 (tt, J = 12.5, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.39–2.30 (m, 1H), 1.95 (dt, J = 17.5, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 1.79–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.54 (tt, J = 7.0, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 1.43–1.29 (m, 2H), 1.28–1.13 (m, 2H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.90 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 6H), 0.78 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.0, 153.0, 144.8, 116.1, 62.9, 61.2, 53.5, 40.9, 37.6, 36.4, 31.3, 29.7, 29.5, 28.9, 28.3, 22.2, 18.5, 16.5, 14.5, 12.4. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M + H]+ C21H34NO3+ = 348.2533, found: 348.2536. Calculated mass [M + Na]+ C21H33NO3Na+ = 370.2353, found: 370.2355. Melting point: 95–97 °C Optical rotation: .

(1 R,2S,8aR)-S-Ethyl 1,2,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-oc-tahydronaphthalene-1-carbothioate (4).

To a solution of ethanethiol (8.3 mL, 115 mmol, 5.9 equiv) in dry THF (200 mL), cooled to 0 °C, was added dropwise n-butyllithium (57.6 mL, 92 mmol, 4.7 equiv). Upon addition a white precipitate formed. After addition, the milk white, now viscous, suspension was allowed to warm to rt. Diels–Alder adduct 3 (8.0 g, 19.6 mmol) in dry THF (50 mL) was added, and the reaction was stirred for 7 h. Full conversion was observed by TLC and GC/MS analysis. The reaction was diluted with ether and quenched by addition of a saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution. The white precipitate dissolved. The phases were separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with ether. The combined organic phases were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellow oil. Upon standing, the oxazolidinone chiral auxiliary crystallized. Pentane was then added to the crystallized product, and the resulting suspension was cooled to −20 °C, where after the cold suspension was filtered over a sintered glass filter (pore size 3). The residue was rinsed with cold pentane (−20 °C) to recover the chiral auxiliary as needle-shaped transparent crystals (2.2 g). The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford crude (1R,2S,8aR)-S-ethyl 1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene-1-carbothioate 4 (7.2 g, 25.7 mmol >99% yield) as a yellowish oil. The product was considered sufficiently pure to be used in the next step.

Alternatively flash column chromatography can be performed: The oil/crystal mixture was dissolved in a minimum amount of ether and loaded on the column. Elution using pentane:ether (98:2) as the eluent afforded pure (1R,2S,8aR)-S-ethyl 1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene-1-carbothioate 4 (5.06 g, 18.0 mmol, 96% yield) as a yellowish oil. (The 96% yield was obtained for a reaction starting from 6.5 g of Diels–Alder adduct 3).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.46 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 2.88 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.79 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 2.02–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.75 (ddt, J = 13.4, 11.5, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 1.53–1.46 (m, 3H), 1.44–1.36 (m, 1H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.21–1.10 (m, 2H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 0.98 (s, 3H), 0.79 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.9, 144.9, 116.0, 56.7, 43.5, 40.6, 36.8, 36.0, 31.4, 29.7, 28.4, 28.2, 23.1, 21.7, 15.9, 14.8, 9.6. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M + H]+ C17H29OS+ = 281.1934, found: 281.1932. Optical rotation: .

((1R,2S8aR)-1,2,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)methanol (5).12,13

To a cooled (0 °C) solution of crude thioester 4 (7.2 g, 25.7 mmol) in dry THF (150 mL) was added portionwise lithium aluminum hydride (4.9 g, 128 mmol, 5 equiv). After addition, the reaction was allowed to warm-up to rt, where after the reaction was heated to 40 °C and stirred for 2 h. GC/MS and TLC analysis indicated complete conversion of the starting material. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, diluted with ether, and carefully quenched using a saturated aqueous Rochelle salt solution. After addition, the quenched reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min. After phase separation, the aqueous layer was extracted three times with ether, where after the combined organic layers were washed with brine. The organic phase was then dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield ((1R,2S,8aR)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)methanol 5 (6.2 g, 30 mmol, quantitative yield) as yellow oil. The material was deemed pure enough to be used in the next step without purification.

Alternatively flash column chromatography can be performed: purification of the obtained yellow oil, using pentane:ether (9:1) as the eluent, afforded pure ((1R,2S,8aR)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)methanol 5 (4.7 g, 21.1 mmol, 91% yield) as a yellowish oil. (The 91% yield reflects that obtained over the past 2 steps, starting from Diels–Alder adduct 3. With 96% isolated yield for the oxazolidinone cleavage, this corresponds to 95% isolated yield for the reduction of thioester 4 to alcohol 5.)

Chiral HPLC analysis of alcohol 5 showed an enantiomeric excess exceeding 98% for the exo isomer. The endo isomer also proved to be enantiomerically enriched, possessing an enantiomeric excess of ~60%.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.43 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (d, J =11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 1.91–1.81 (m, 1H), 1.81–1.71 (m, 2H), 1.70–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.51 (m, 2H), 1.38 (s, 1H), 1.28–1.14 (m, 2H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.86 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 0.51 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.1, 116.1, 65.8, 41.1, 39.3, 38.1, 36.3, 31.9, 31.3, 29.9, 28.9, 27.7, 22.3, 15.1, 11.6. HRMS: (ESI+) Calculated mass [M + H]+ C15H27O+ = 223.2056, found: 223.2059. Chiral HPLC analysis on a Chiracel AD-H column, n-heptane: i-PrOH = 98:2, 40 °C, flow =0.5 mL/min, UV detection at 190 nm, 210 and 254 nm, retention times (min): 15.7 (endo minor), 15.1 (endo major), 17.7 (exo major), and 21.1 (exo minor, not detected for chiral alcohol 5)

(1R,2S,8aR)-1,2,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene-1-carbaldehyde (6).12,13

To a solution of alcohol 5 (4.7 g, 21.1 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (80 mL) were added TPAP (371 mg, 1.06 mmol, 5 mol %), 4-methylmorpholine-N-4-oxide (or its monohydrate) (3.22 g, 27.5 mmol, 1.3 equiv), and 3 Å molecular sieves. The reaction was stirred at rt for 2 h after which TLC and GC/MS analysis indicated complete conversion of the starting material. The reaction mixture was diluted using pentane which resulted in precipitation of the TPAP. The mixture was filtered over Celite to remove the TPAP. NMO and its reduced analogue were removed by flash column chromatography using pentane:ether (95:5) as the eluent to afford pure (1R,2S,8aR)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene-1-carbaldehyde 6 (4.43 g, 20.1 mmol, 95% yield) as a yellowish oil which crystallized upon standing.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.38 (s, 1H), 5.52–5.47 (m, 1H), 2.50 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1H), 2.00–1.91 (m, 1H), 1.90–1.80 (m, 1H), 1.80–1.69 (m, 1H), 1.57–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.45–1.37 (m, 1H), 1.36–1.28 (m, 1H), 1.27–1.14 (m, 2H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 0.80 (s, 3H), 0.78 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.2, 143.9, 116.6, 52.3, 40.6, 38.2, 36.3, 32.7, 30.5, 29.7, 29.1, 28.7, 21.8, 16.1, 7.5. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M + H]+ C15H25O+ = 221.1900, found: 221.1901. Melting point: 52–53 °C.

(E)-4-((1S,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)but-3-en-2-one (7).12,13

A solution of NaHMDS (30 mL, 2 M in THF, 30 mmol, 3 equiv) diluted to a 1 M solution with dry THF (30 mL) was cooled to −78 °C. The orange solution became slightly turbid and viscous, however stirring was assured. Acetone (4.4 mL, 60.3 mmol, 3 equiv) was added dropwise to the turbid solution which became clear upon addition. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 20 min, after which a solution of aldehyde 6 (4.43 g, 20.1 mmol) in dry THF (125 mL) was added dropwise over 20 min by the aid of a dropping funnel. After addition, the reaction was taken out of the cooling bath and allowed to warm-up to rt (by the aid of a water bath at rt). The reaction was stirred for 2 h after which TLC and GC/MS indicated complete consumption of the aldehyde 6.

The reaction was diluted with ether and quenched with a saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution. The phases were separated, and the organic phase was washed with distilled water and brine. The combined aqueous layers were back-extracted once with ether, and the combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash column chromatography employing pentane:ether (95:5) afforded (E)-4-((1S,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)but-3-en-2-one 7 as an amorphous solid (3.4 g, 13.1 mmol, 65% yield)

Note: The aldol condensation was also performed on a 3.5 g scale which resulted in a slightly higher isolated yield of 74%. It is very important to monitor the reaction and not let it run overnight. This gives overcondensation and therefore lowers isolated yields.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.60 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.02 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 2.13 (d, J =13.1,Hz, 1H), 1.93 (dt, J = 17.8, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 1.80–1.68 (m, 1H), 1.62–1.34 (m, 5H), 1.17 (dd, J = 12.6, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.96–0.89 (m, 1H), 0.78 (s, 3H), 0.72 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.7, 158.2, 144.7, 129.6, 116.5, 43.7, 40.8, 36.7, 36.2, 31.1, 29.7, 29.3, 28.3, 27.4, 22.0, 16.4, 10.3. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M + H]+ C18H29O+ = 261.2213 found: 261.2215. Calculated mass [M + Na]+ C18H28ONa+ = 283.2032, found: 283.2034. Melting point: 70–72 °C

4-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)butan-2-one (8).12,13

To a solution of α,β-unsaturated ketone 7 (3.4 g, 13.1 mmol) in dry (CH2)2Cl2 (150 mL) were added Wilkinson’s catalyst (909 mg, 0.98 mmol, 7.5 mol %) and triethylsilane (10.4 mL, 65.5 mmol, 5 equiv). The reaction mixture was heated to reflux and stirred for 90 min after which TLC indicated complete conversion of the starting material. The reaction was cooled to rt, where after it was quenched with an aqueous solution of HCl (6 M, 100 mL). The mixture was stirred for 30 min after which the phases were separated, and the organic layer was washed with water, followed by a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash column chromatography employing pentane:ether (95:5) afforded pure 4-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)butan-2-one 8 (3.1 g, 11.7 mmol, 90% yield) as a slightly yellow oil.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.41 (s, 1H), 2.37–2.28 (m, 2H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 1.99 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 1.88–1.60 (m, 4H), 1.60–1.32 (m, 6H), 1.17 (td, J = 13.0, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 0.98 (s, 3H), 0.78 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.63 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 209.6, 145.9, 116.3, 41.0, 40.1, 37.8, 36.7, 36.2, 33.6, 31.6, 30.2, 30.1, 29.8, 29.0, 27.6, 22.3, 16.0, 15.1.

Ethyl 3-Methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-enoate (9).13

Ethyl 2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acetate (6.96 mL, 35.1 mmol, 3 equiv) in dry THF (50 mL) was added dropwise to a suspension of sodium hydride (1.4 g, 60% in oil, 35.1 mmol, 3 equiv) in dry THF (50 mL) at 0 °C by the aid of a dropping funnel. The suspension turned into a clear solution and was stirred for 20 min after which ketone 8 (3.1 g, 11.7 mmol) in dry THF (100 mL) was added dropwise over 10 min by the aid of a dropping funnel. The cooling bath was removed, and the mixture was allowed to warm to rt. The reaction vessel was then sealed under N2 and placed in an oil bath at 80 °C and was allowed to stir for 6 h. TLC and GC/MS indicated full conversion of the starting material.

The reaction was cooled to rt and quenched with saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The reaction mixture was diluted with ether, and the phases were separated. The aqueous phases was extracted with ether were after the combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellow oil. Flash column chromatography employing pentane:ether (95:5) afforded crude ethyl 3-methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-enoate 9 (4.0 g, 12.0 mmol, 103%) as an E/Z mixture of ~9:1. Note: The sodium hydride was prewashed three times with pentane to remove the oil.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.67 (s, 1H), 5.45–5.40 (m, 1H), 41.3,(q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.17 (s, 3H), 2.13 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (dt, J = 10.1, 4.4 Hz, 2H), 1.90–1.67 (m, 4H), 1.65–1.44 (m, 5H), 1.44–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.26 (d, J =6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.22–1.14 (m, 1H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 0.99 (s, 3H), 0.81 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.63 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.9, 161.3, 146.0, 116.3, 115.3, 59.5, 41.0, 40.0, 37.2, 36.2, 34.7, 34.6, 33.5, 31.7, 29.9, 29.1, 27.6, 22.3, 19.2, 16.3, 15.2, 14.5.

(E)-3-Methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-en-1-ol (Tuberculosinol).12,13

To a solution of crude enoate 9 (4.0 g, 12.0 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (75 mL) cooled to −78 °C was added dropwise DIBAL-H (36.0 mL, 1.0 M in CH2Cl2, 36.0 mmol, 3 equiv) over 15 min by the aid of a dropping funnel. The cooling bath was removed, and the reaction was allowed to slowly warm up to rt. TLC and GC/MS indicated complete conversion of the starting material after 1 h of reaction time.

The reaction mixture was carefully quenched using MeOH (10 mL), where after saturated aqueous Rochelle salt solution (75 mL) was added at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred for 30 min while warming up to rt, where after the phases were separated. The aqueous phase was extracted three times with CH2Cl2, and the combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellowish oil. Flash column chromatography was executed using pentane:ether (4:1) as the eluent, affording pure (E)-3-methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-en-1-ol (2.33 g, 8.0 mmol, 68% yield) as a colorless oil. A mixture of (E)-tuberculosinol and (Z)-tuberculosinol was also obtained (0.9 g). This was subjected to an additional chromatographic purification (pentane:ether = 5:1), affording 460 mg of (E)-tuberculosinol, giving a combined yield of 82%. Also (Z)-tuberculosinol (0.4 g, 1.4 mmol, 11%) was isolated as a colorless oil.

Analytical Data for (E)-Tuberculosinol.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.43–5.33 (m, 2H), 4.08 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.57 (s, 1H), 2.13, (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 1.92–1.85 (m, 2H), 1.81–1.67 (m, 3H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.59–1.28 (m, 6H), 1.28–1.10 (m, 1H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 0.97 (s, 3H), 0.78 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.59 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146., 140.1, 123.1, 116.1, 59.1, 40.9, 39.8, 36.9, 36.1, 35.0,33.4, 32.8, 31.7, 29.8, 29.0, 27.4, 22.3, 16.5, 16.2, 15.1. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M+Na+]+ C20H34ONa+ = 313.2502, found: 313.2500. Optical rotation: and .

Analytical Data for (Z)-Tuberculosinol.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.46–5.42 (m, 1H), 5.39 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 1.99 (ddp, J = 17.4, 12.6, 5.3 Hz, 3H), 1.91–1.79 (m, 1H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.67–1.47 (m, 4H), 1.47–1.15 (m, 6H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 0.85 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.62 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.8, 139.9, 123.9, 116.0, 58.7, 40.9, 39.7, 37.0, 36.0, 35.3, 33.2, 31.6, 29.7, 29.0, 27.5, 25.4, 23.6, 22.2, 16.0, 15.1.

(4aS,5R,6S)-5-((E)-5-Chloro-3-methylpent-3-en-1-yl)-1,1,5,6-tetramethyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydronaphthalene (10).

To a suspension of 1-chloropyrrolidine-2,5-dione (1.0 g, 7.61 mmol, 1.3 equiv) in dry CH2Cl2 (15 mL), cooled to −20 °C, was added dropwise dimethyl sulfide (0.65 mL, 8.78 mmol, 1.5 equiv) in dry CH2Cl2 (5.0 mL). The milk white suspension was allowed to warm to 0 °C for 15 min, after which the temperature was lowered to −40 °C. Tuberculosinol (1.7 g, 5.85 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added slowly by the aid of a syringe pump over 15 min. After addition, the cooling bath was removed, and the reaction was allowed to warmup to rt. The reaction was allowed to stir at this temperature for 2 h, after which TLC and GC/MS analysis indicated complete conversion of the tuberculosinol. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and treated with pentane upon which succinimide oiled out. The mixture was decanted and filtered, and the elute was concentrated under reduced pressure affording nearly pure (4aS,5R,6S)-5-((E)-5-chloro-3-methylpent-3-en-1-yl)-1,1,5,6-tetramethyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydronaphthalene 10 (1.85 g, 6.0 mmol, > 99% yield) as a yellow oil contaminated only with DMSO formed during the reaction.

Analytical Data for (E)-Tuberculosinyl Chloride.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.51–5.41 (m, 2H), 4.09 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 2.16 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 1.96 (dt, J = 10.4, 4.6 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (ddd, J = 17.7, 14.5, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 1.75 (s, 3H), 1.72 (s, 1H), 1.63–1.25 (m, 7H), 1.20 (td, J = 12.9, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.82 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.63 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.1, 144.0, 119.9, 116.3, 41.3, 41.1, 39.9, 37.1, 36.2, 34.8, 33.5, 32.9, 31.8, 29.9, 29.1, 27.6, 22.4, 16.5, 16.3, 15.2. HRMS: (APCI) calculated mass [M-Cl−]+ C20H33+ = 273.2582, found: 273.2576

Analytical Data for (Z)-Tuberculosinyl Chloride.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.46–5.42 (m, 1H), 5.39 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 1.99 (ddp, J = 17.4, 12.6, 5.3 Hz, 3H), 1.91–1.79 (m, 1H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.67–1.47 (m, 4H), 1.47–1.15 (m, 6H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 0.85 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.62 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.8, 139.9, 123.9,116.0, 58.7, 40.9, 39.7, 37.1, 36.0, 35.3, 33.2, 31.6, 29.7, 29.0, 27.5, 25.4, 23.6, 22.2, 16.0, 15.1.

6-Amino-9-((2R,3R,4S,5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-1-((E)-3-methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-en-1-yl)-9H-purin-1-ium (1-TbAd).6

To a solution (0.5 M) of nearly pure tuberculosinyl chloride 10 (1.8 g, 5.8 mmol) in peptide grade DMF (11.6 mL) were added sodium iodide (1.05 g, 7.0 mmol, 1.2 equiv) and adenosine (1.87 g, 7.0 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The suspension was stirred in the dark at rt overnight, forming a dark turbid solution. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and subsequently purified using flash column chromatography (15% MeOH in CH2Cl2) affording 1-TbAd (2.4 g, 4.43 mmol, 76% yield) The reaction can also be performed in dimethylacetamide as the solvent. Starting from tuberculosinyl chloride 10 (0.4 g, 1.29 mmol), 1-TbAd (560 mg, 1.04 mmol, 79% yield) was obtained.

Note: 1-TbAd proved to be difficult to separate from unreacted adenosine due to tailing of the 1-TbAd. It is recommended to use a long column (30 cm) and analyze individual fractions by 1H NMR analysis to determine the presence of free adenosine. Visualization of the adenosine on a TLC plate proved to be difficult.

Analytical Data for Naturally Occurring 1-TbAd.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.62 (s, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 6.08 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 5.51–5.42 (m, 2H), 4.91 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.62 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 4.58 (s, 1H), 4.38–4.31 (m, 2H), 4.15 (q, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (dd, J = 12.3, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (dd, J = 12.2, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 2H), 2.12–2.04 (m, 2H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.87–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.84–1.71 (m, 2H), 1.65–1.47 (m, 5H), 1.47–1.36 (m, 3H), 1.21 (ddd, J = 12.7, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.85 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.66 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 152.5, 147.8, 147.6, 147.3, 147.1, 143.7, 121.5, 117.3, 115.9, 90.4, 87.4, 76.4, 71.8, 62.6, 49.4, 42.0, 41.1, 38.1, 36.9, 35.9, 34.5, 33.9, 32.6, 30.3, 29.5, 28.5, 23.2, 17.4, 16.6, 15.5. HRMS: (ESI+) Calculated mass [M]+ C30H46N5O4+ = 540.3544, found: 540.3542.

Analytical Data for Non-Natural (Z)-1-TbAd Constructed from (Z)-Tuberculosinyl Chloride.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.56 (2× s, 2H), 8.41 (2× s, 1H), 6.09–6.02 (m, 1H), 5.44 (dt, J = 23.8, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 4.88 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.61 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (t, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.14 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.91–3.82 (m, 1H), 3.76 (dd, J = 12.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.14 (m, 2H), 2.07 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 1.88 (s, 3H), 1.85–1.71 (m, 3H), 1.65–1.47 (m, 5H), 1.43 (dd, J = 14.6, 8.6 Hz, 2H), 1.22 (dd, J = 12.4, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.02 (2× s, 3H), 0.86 (2× d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.66 (2× s, J = 10.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 152.7, 152.5, 147.8, 147.6, 147.3, 147.1, 147.0, 143.6, 143.4, 121.6, 121.5, 117.2, 117.2, 116.5, 116.0, 90.4, 87.4, 76.2, 71.7, 62.6, 42.0, 41.9, 41.0, 38.2, 38.0, 36.9, 36.9, 35.8, 34.4, 34.3, 33.8, 32.6, 30.3, 29.5, 28.7, 28.5, 26.8, 23.9, 23.2, 23.1, 17.5, 16.6, 16.6, 15.8, 15.6. HRMS: (ESI+) Calculated mass [M]+ C30H46N5O4+ = 540.3544, found: 540.3542. Note: The appearance of additional signals in the NMR spectra of (Z)-1-TbAd, compared to that of naturally occurring (E)-1-TbAd, is attributed to rotamers.

13C-Labeled 1-TbAd.

To a solution (0.5 M) of nearly pure tuberculosinyl chloride (142 mg, 0.459 mmol, 1.25 equiv) in peptide grade DMF (0.92 mL) were added sodium iodide (69 mg, 0.459 mmol, 1.25 equiv) and [1’,2’,3’,4’,5’,-13C5] adenosine (100 mg, 0.367 mmol). The suspension was stirred in the dark at rt overnight, forming a dark turbid solution. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure where after purified using flash column chromatography (15% MeOH in CH2Cl2) affording [1’,2’,3’,4’,5’,-13C5] 1-TbAd (100 mg, 0,18 mmol, 57% yield) as an off-white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 6.26 (s, 1H), 5.84 (s, 1H), 5.52–5.40 (m, 2H), 4.58 (s, 1H), 4.51 (s, 1H), 4.42 (s, 1H), 4.33 (s, 1H), 4.14 (s, 1H), 4.04 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 3.77–3.63 (m, 1H), 3.59 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 2.22 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 2H), 2.07 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 1.88 (s, 3H), 1.86–1.70 (m, 3H), 1.65–1.47 (m, 4H), 1.47–1.35 (m, 2H), 1.21 (td, J = 12.4, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.84 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.65 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 152.6, 147.8, 147.3, 147.1, 147.0, 143.6, 121.6, 117.3, 116.0, 90.4 (dd, J = 42.0, 3.7 Hz), 87.4 (t, J = 41.7, 38.5 Hz), 76.2 (dd, J = 42.0, 37.8 Hz), 71.7 (td, J = 38.1, 3.8 Hz), 62.6 (d, J = 41.7 Hz), 49.9, 42.0, 41.0, 38.0, 36.9, 35.8, 34.5, 33.8, 32.6, 30.3, 29.5, 28.5, 23.1, 17.4, 16.6, 15.5. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M + H]+ C25(13C)5H46N5O4+ = 545.3712 found: 545.3702.

(2R,3S,4R,5R)-2-(Hydroxymethyl)-5-(6-(((E)-3-methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-en-1-yl)amino)-9H-purin-9-yl)-tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol (N6-TbAd):7

A solution of 1-TbAd (550 mg, 1.02 mmol) in 60% Me2NH in water (5.5 mL) was stirred for 90 min. NMR analysis indicated complete conversion of the 1-TbAd. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and subsequently subjected to flash column chromatography, with 15% MeOH in CH2Cl2, to afford N6-TbAd as a white solid (550 mg, 1.02 mmol, quantitative yield) as yellowish oil. Note: The rearrangement could be performed with similar results using Et2NH or iPr2NEt (2 M) in MeOH.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.23 (s, 1H), 5.95 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 5.51–5.44 (m, 1H), 5.41 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 4.35–4.29 (m, 1H), 4.20 (s, 1H), 4.17 (s, 1H), 3.89 (dd, J = 12.6, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (dd, J = 12.9, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 2.24 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 2.07–1.93 (m, 3H), 1.91–1.82 (m, 2H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 1.65–1.49 (m, 4H), 1.49–1.36 (m, 3H), 1.21 (td, J = 11.9, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 3H), 0.85 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.65 (s, 3H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.19 (s, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 5.86 (bs, 1H), 5.82 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (s, 1H), 4.47 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (s, 1H), 4.19 (bs, 2H), 3.94 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (s, 2H), 2.49 (bs, 2H), 2.16 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 2.01–1.90 (m, 2H), 1.85 (d, J = 23.8 Hz, 2H), 1.76 (s, 3H), 1.72 (s, 1H), 1.64–1.28 (m, 6H), 1.21 (tt, J = 13.0, 6.2 Hz, 2H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.82 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.63 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.6, 152.4, 147.0, 146.1, 141.7, 140.1, 120.7, 119.0, 116.2, 91.1, 87.6, 73.9, 72.5, 63.2, 41.0, 39.9, 38.9, 37.0, 36.2, 35.0, 33.5, 32.8, 31.7, 29.9, 29.1, 27.5, 22.3, 16.8, 16.3, 15.2. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M + H]+ C30H46N5O4+ = 540.3544 found: 540.3542.

6-Amino-9-((2R,4S,5R)-4-hydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-1-((E)-3-methyl-5-((1R,2S,8aS)-1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydronaphthalen-1-yl)pent-2-en-1-yl)-9H-purin-1-ium (2’-deoxy 1-TbAd).

To a solution (0.5M) of nearly pure tuberculosinyl chloride 10 (300 mg, 0.97 mmol) in peptide grade DMA (2 mL) were added sodium iodide (175 mg, 1.17 mmol, 1.2 equiv) and 2’-deoxy-adenosine monohydrate (314 mg, 1.17 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The suspension was stirred in the dark at rt overnight, forming a dark turbid solution. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and subsequently purified using flash column chromatography (15% MeOH in CH2O2) affording 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd (190 mg, 0.36 mmol, 37% yield) as a white solid. Also a slightly impure fraction of 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd (150 mg, 0.29 mmol, 31%) was obtained. The impurity, based on NMR analysis, remained unresolved.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.44 (s, 1H), 6.46 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 5.46 (s, 2H), 4.90 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 4.57 (s, 1H), 4.09–4.01 (m, 1H), 3.77 (qd, J = 12.1, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (dt, J = 13.0, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 2.56–2.44 (m, 1H), 2.21 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 2H), 2.11–1.99 (m, 2H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.86–1.70 (m, 3H), 1.54 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 4H), 1.42 (dd, J = 17.1, 8.8 Hz, 2H), 1.19 (td, J = 12.3, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.83 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 0.64 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.5, 147.7, 147.05, 146.99, 146.95, 143.5, 117.2, 116.1, 89.5, 86.3, 72.3, 63.0, 49.9, 42.0, 41.8, 41.0, 38.0, 35.8, 34.5, 33.9, 32.6, 30.3, 29.5, 28.5, 23.1, 17.5, 16.6, 15.6. HRMS: (ESI+) calculated mass [M]+ C30H46N5O3+ = 524.3595, found: 524.3588.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.J.M. acknowledges The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-CW) for a VICI grant. Mrs Tiemersma is kindly acknowledged for HRMS analysis. Dr. J. Poater, and Dr. R. W. A. Havenith are acknowledged for their input regarding the computational chemistry.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01332.Associated analytical data (1H NMR, 13C NMR, and APT spectra for all compounds, CID-MS of 2’-deoxy 1-TbAd, and computational data (PDF) Crystallographic data (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Global Tuberculosis Report, 2015. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (date accessed 01/24/2015).

- (2).Sturgill-Koszycki S; Schlesinger PH; Chakraborty P; Haddix PL; Collins HL; Fok AK; Allen RD; Gluck SL; Heuser J; Russell DG Science 1994, 263, 678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).The mycobacterial cell envelope; Daffé M, Reyrat J-M, Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sartain MJ; Dick DL; Rithner CD; Crick DC; Belise JT J. Lipid Res 2011, 52, 861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Layre E; Sweet L; Hong S; Madigan CA; Desjardins D; Young DC; Cheng T-Y; Annand JW; Kim K; Shamputa IC; McConnell MJ; Debona CA; Behar SM; Minnaard AJ; Murray M; Barry CE III; Matsunaga I; Moody DB Chem. Biol 2011, 18, 1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Layre E; Lee HL; Young DC; Martinot AJ; Buter J; Minnaard AJ; Annand JW; Fortune SM; Snider BB; Matsunaga I; Rubin EJ; Alber T; Moody DB Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A 2014, 111, 2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Young DC; Layre E; Pan S-J; Tapley A; Adamson J; Seshadri C; Wu Z; Buter J; Minnaard AJ; Coscolla M; Gagneux S; Copin R; Ernst JD; Bishai WR; Snider BB; Moody DB Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lau SKP; Lam C-W; Curreem SOT; Lee K-C; Lau CCY; Chow W-N; Ngan AHY; To KKW; Chan JFW; Hung IFN; Yam W-C; Yuen K-Y; Woo PCY Emerging Microbes Infect. 2015, 4, e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wallis RS; Kim P; Cole S; Hanna D; Andrade BB; Maeurer M; Schito M; Zumla A Lancet Infect. Dis 2013, 13, 362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pan S-J; Tapley A; Adamson J; Little T; Urbanowski M; Cohen K; Pym A; Almeida D; Dorasamy A; Layre E; Young DC; Singh R; Patel VB; Wallegren K; Ndung’u T; Wilson D; Moody DB; Bishai WJ Infect. Dis 2015, 212, 1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pethe K; Swenson DL; Alonso S; Anderson J; Wang C; Russell DG Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101, 13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Spangler JE; Carson CA; Sorensen EJ Chem. Sci 2010, 1, 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Maugel N; Mann FM; Hillwig ML; Peters RJ; Snider BB Org. Lett 2010, 12, 2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14) (a).Nakano C; Okamura T; Sato T; Dairi T; Hoshino T Chem. Commun 2005, 1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mann FM; Xu M; Chen X; Fulton DB; Russell DG; Peters RJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 17526; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) A correction regarding reference 14b was published by the same authors: 2010, 132, 10953. [Google Scholar]

- (15) (a).Knapp S; Sharma S J. Org. Chem 1985, 50, 4996. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanis SP; Abdallah YM Synth. Commun 1986, 16, 251. [Google Scholar]

- (16) (a).Brohm D; Waldmann H Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3995. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brohm D; Philippe N; Metzger S; Bhargava A; Müller O; Lieb F; Waldmann H J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 13171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) A recent study demonstrates that the use of a bulky Lewis acid catalyst leads to the exo product, see: Zhou J-H; Jiang B; Meng F-F; Xu Y-H; Loh T-P Org. Lett 2015, 17, 4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yoon T; Danishefsky SJ; de Gala S Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1994, 33, 853. [Google Scholar]

- (18) For 6,6-dimethyl-1-vinylcyclohexene 1 as the diene, see refs 12, 13, 15b, 16, 17 and: (a).Hosoi H; Kawai N; Suzuki T; Nakazaki A; Takao K; Umezawa K; Kobayashi S Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4961. [Google Scholar]; (b) de Miranda DS; da Conceição GJA; Zukerman-Schpector J; Guerrero MA; Schuchardt U; Pinto AC; Rezende BM; Marsaioli AJJ J. Braz. Chem. Soc 2001, 12, 391. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Buter J On the total synthesis of terpenes containing quaternary stereocenters: Stereoselective synthesis of the taiwaniaqui-noids, mastigophorene A, and tuberculosinyl adenosine. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Groningen, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Miyata O; Shinada T; Ninomiya I; Naito T Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 2421. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Evans DA; Chapman KT; Bisaha JJ Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 1238. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Nakano C; Hoshino T ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23) (a).Sato T; Hoshino T Biosci. Biotechnol., Biochem 2001, 65, 2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoshino T; Sato T Chem. Commun 1999, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tokuyama H; Yokoshima S; Yamashita T; Lin S-C; Li L; Fukuyama TJ Braz. Chem. Soc 1998, 9, 381. [Google Scholar]

- (25) (a).Davisson VJ; Woodside AB; Neal TR; Stremler KE; Muehlbacher M; Poulter CD J. Org. Chem 1986, 51, 4768. [Google Scholar]; (b) Woodside AB; Huang Z; Poulter CD Org. Synth 1988, 66, 211. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Jones JW; Robins RK J. Am. Chem. Soc 1963, 85, 193. [Google Scholar]

- (27) For representative reviews on the Dimroth rearrangement see: (a).Fujii T; Itaya T Heterocycles 1998, 48, 359. [Google Scholar]; (b) El Ashry ESH; Nadeem S; Sha MR; El Kilany Y Adv. Heterocycl Chem 2010, 101, 161. [Google Scholar]; (c) El Ashry ESH; El Kilany Y; Rashed N; Assafir H Adv. Heterocycl. Chem 1999, 75, 79. [Google Scholar]

- (28) For selected reviews highlighting s-cis/s-trans equilibria see: (a).Evans DA; Johnson JS In Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis; Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto Y, Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1999; Chapter 33: Diels-Alder Reactions. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dias LC J. Braz. Chem. Soc 1997, 8, 289. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lam Y-H; Cheong PH-Y; Blasco Mata JM; Stanway SJ; Gouverneur V; Houk KN J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).te Velde G; Bickelhaupt FM; Baerends EJ; Fonseca Guerra C; van Gisbergen SJA; Snijders JG; Ziegler TJ Comput. Chem 2001, 22, 931. [Google Scholar]

- (31) (a).Becke AD Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys 1988, 38, 3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perdew JP Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 1986, 33, 8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32) (a).Seeman JI Chem. Rev 1983, 83, 83. [Google Scholar]; (b) Seeman JI J. Chem. Educ 1986, 63, 42. [Google Scholar]

- (33) (a).Wolters LP; Bickelhaupt FM WIRES Comput. Mol. Sci 2015, 5, 324–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bickelhaupt FM J. Comput. Chem 1999, 20, 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fukami A; Ikeda Y; Kondo S; Naganawa H; Takeuchi T; Furuya S; Hirabayashi Y; Shimioike K; Hosaka S; Watanabe Y; Umezawa K Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 1201. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sullivan BW; Faulkner DJ J. Org. Chem 1986, 51, 4568. [Google Scholar]

- (36).De Rosa S; Crispina A; De Giulio A; Iodice C; Amodeo P; Tancredi TJ Nat. Prod 1999, 62, 1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rijo P; Gaspar-Marques C; Simeões MF; Jimeno ML; Rodríguez B Biochem. Syst. Ecol 2007, 35, 215. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Swersey JC; Barrows LR; Ireland CM Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 6687. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.