KL1

HIV/AIDS, global health and the Sustainable Development Goals

K De Cock

CDC Country Office, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nairobi, Kenya

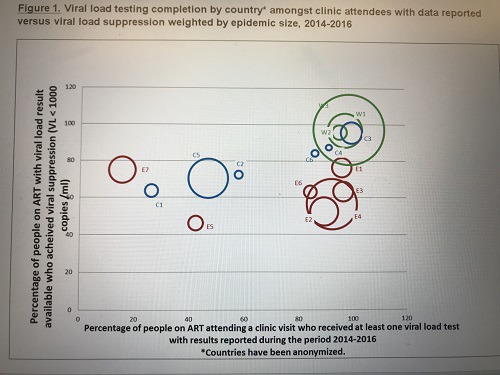

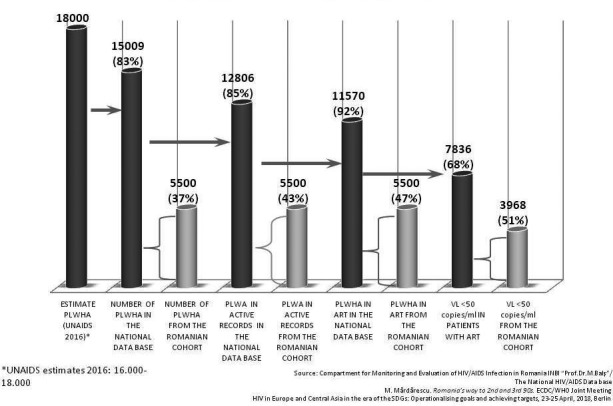

Sustainable Goal (SDG) 3 calls for an end to the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases by 2030, and the concomitant UNAIDS Fast‐Track Strategy aims to reduce new HIV infections to no more than 500,000 annually by 2020 and 200,000 by 2030. Central to the global effort is the UNAIDS 90‐90‐90 initiative which requires 90% of persons with HIV to be diagnosed, 90% of those to receive ART and 90% of the treated to be virally suppressed. There is controversy around how “the end of AIDS” is defined, about whether this ambitious goal is achievable and whether AIDS exceptionalism is still appropriate. UNAIDS has targeted 30 million people to be on ART by 2020, when fiscal requirements are expected to be 26 billion US dollars annually; current expenditure is about 7 billion US dollars less. This presentation will review progress in the AIDS response in the overall context of current global health. It honours Jacqueline Van Tongeren and Joep Lange and their work, and is dedicated to their memory.

KL2

Strategies to reduce HIV incidence in Europe

A Pharris

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Stockholm, Sweden

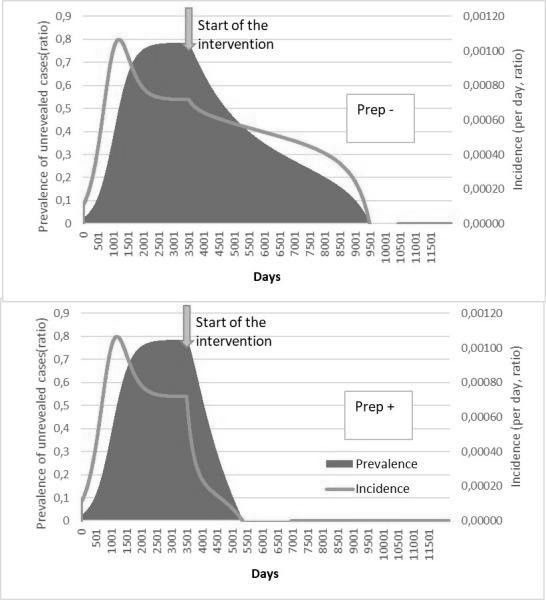

HIV incidence is increasing in the European region as a whole, although there are large epidemiological differences between Western, Central and Eastern Europe. Whilst overall 80% of people in the European region have been diagnosed with HIV, this varies greatly across sub‐regions with 86%, 83% and 76% of people diagnosed in Western, Central and Eastern Europe respectively. Among those diagnosed, 64% are estimated to be on treatment and this, too, differs across the region with 90%, 73% and 46% of those diagnosed on treatment in Western, Central and Eastern sub‐regions, respectively. Among those on treatment in the European region, 85% are virally suppressed with variations across sub‐regions in Europe (92%, 78% and 74% in Western, Central and Eastern). Within sub‐regions and among key populations within countries there is considerable diversity in diagnosis, proportion on treatment and viral suppression rates. While some countries within the region have been successful in meeting and surpassing the 90‐90‐90 targets, others are facing enormous challenges and are lagging behind. While the tools to prevent HIV – including diversified testing strategies, treatment as prevention, PrEP and harm reduction – have multiplied in recent years, their application across Europe is uneven and, in most settings, far lower than needed to impact incidence. Differences in epidemiology of HIV and health systems across Europe necessitate context‐specific strategies to strengthen and control HIV prevention and care efforts.

KL3

PrEP: what's happening in Europe and the world in general

S McCormack

MRC Clinical Trials Unit, University College London, London, UK

Within and beyond Europe, PrEP is undoubtedly contributing to the decline in new diagnoses reported in gay and other MSM, but the public health benefit is difficult to assess precisely and the impressive decline seen in some city clinics is not universal. San Francisco, central London and New South Wales have seen the largest gains. In all these settings testing and treatment were already at scale when PrEP was introduced. The contribution of PrEP to the toolkit is most accurately captured in New South Wales where they observed a 35% reduction in state‐wide new HIV diagnoses in MSM following rapid scale‐up of PrEP in the EPIC trial, two seroconversions amongst 3927 years of follow‐up amongst trial participants [1]. TDF/FTC PrEP is extremely effective biologically, but it is costly and needs to be delivered as part of a comprehensive package of interventions to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections including HIV – a package that is not available to everyone in Europe or globally in spite of the current burden of sexually transmitted infections. Introducing PrEP is therefore an opportunity to strengthen prevention services, and one of the most cost‐efficient methods is to employ key populations to deliver services when and where convenient to eligible peers (AIDS 2018). Adherence remains the Achilles heel for PrEP, and the products in the pipeline may go some way to addressing this: vaginal rings, long‐acting injectables and implants. However, first and foremost is the need to empower key populations with the information they need to understand their risk of HIV/STIs and how to reduce this during the various phases of their sexual lifetime.

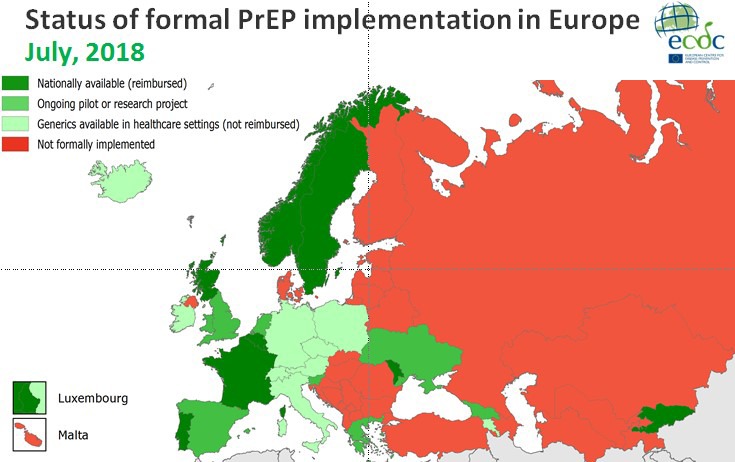

Abstract KL3 – Figure 1. Status of formal PrEP implement in Europe.

Reference

[1] Grulich et al. Rapid reduction in HIV diagnoses after targeted PrEP implementation in NSW, Australia. CROI 2018; Abs 88.

Oral Abstracts O11 – Living Well with HIV: Ongoing Challenges

O111

Retention and re‐engagement in care: a combination approach again required

F Burns

Centre for Sexual Health and HIV Research, and Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

Effective ART remains the cornerstone of successful HIV management, with life expectancy in those successfully treated similar to that of the general population. ART is also an effective means of reducing population HIV transmission with the goal of zero new infections. However, suboptimal engagement in HIV care threatens to derail this success and is associated with serious consequences for both individual and public health. Engagement in care for any individual is dynamic and disengagement may happen at any time. Indeed, in the UK as many as one in four HIV clinic appointments are missed. While ‘living well with HIV’ is the current mantra, it is still denied to many. The population groups most at risk of disengagement are invariably those most marginalised and with the least advocacy. They include people who struggle with HIV‐related stigma, those with insecure residency and/or employment and people living with mental health, alcohol and drug dependency issues – problems that may increase in the current political and economic environment. Sustainable engagement will require a combination of biomedical, behavioural and structural strategies that recognise and address individual level factors and create a more enabling environment for health over the life course. Community participation and partnership in this process will be vital, with peer and social support services playing a key role. To tailor and target interventions appropriately, mechanisms are needed to predict those at risk of subsequent disengagement as well to respond once this occurs. Effective mechanisms for predicting and monitoring engagement are either limited or lacking, and the pool of evidence‐based interventions to improve engagement small. Future investment in research and services to tackle engagement is required to ensure the health inequalities we see across our cohorts reduced.

O112

HIV and aging: challenges and goals

J Falutz

Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Currently, overall long‐term survival of treated PLWHIV world‐wide approaches that of the general population. An increasing minority will live as long as their seronegative peers. As a result, the average age of PLWHIV, currently in the mid‐50s in resource‐rich countries, has increased. The proportion of older PLWHIV who are long‐term survivors compared to those who seroconvert at an older age varies according to local factors. The salutary impact on survival has nevertheless been challenged by several developments. The increasing proportion of PLWHIV approaching a typical geriatric age range will significantly impact health care delivery; their clinical features are similar to that of the general population about 5 to 10 years older. In addition to the earlier occurrence of common age‐related conditions, with increased multimorbidity compared to controls, several common geriatric syndromes have also impacted this younger population. These often difficult‐to‐evaluate and ‐manage conditions may include: sarcopenia, impaired mobility and falls, sensory complaints (neuropathy, visual and auditory deficits), cognitive decline and, significantly, frailty. This latter condition, a state of increased vulnerability to biologic and environmental stressors, with reduced ability to maintain homeostasis, remains challenging to evaluate and operationalize. In the general population, a simple and reliable metric to diagnose frailty in the usual clinical setting remains elusive. This is compounded by the poorly understood biologic basis for frailty, distinct from its increased risk of concurrent disabilities and comorbidities. Research into common determinants of frailty between the geriatric population and PLWHIV related to immune‐senescence, chronic inflammation, epigenetics and mitochondriopathy provide clues to potential avenues for prevention and management. Frailty may be key to understanding the discordance between chronologic and biologic age. Concurrently, investigation of predictors of successful aging in PLWHIV is progressing. Insights into the concepts of both psychological and physical resilience in seronegatives may be an important bridge contributing not only to increased lifespan but also to improved health‐span for PLWHIV.

O113

48‐week changes in biomarkers in subjects with high cardiovascular risk switching from ritonavir‐boosted protease inhibitors to dolutegravir: the NEAT022 study

E Martinez1, L Assoumou2, G Moyle3, L Waters4, M Johnson5, P Domingo6, J Fox7, H Stellbrink8, G Guaraldi9, M Masia10, M Gompels11, S de Wit12, E Florence13, S Esser14, F Raffi15, A Pozniak3, J Gatell16

1Infectious Diseases, Hospital Clínic & University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. 2Institut Pierre Louis d’Épidémiologie et de Santé, INSERM, Sorbonne Universités, Paris, France. 3St Stephen's AIDS Trust, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK. 4Mortimer Market Centre, Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. 5Infectious Diseases, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK. 6Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain. 7Infectious Diseases, Guy's and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK. 8Infectious Diseases, Infektionsmedizinisches Centrum, Hamburg, Germany. 9Infectious Diseases, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy. 10Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital de Elche, Elche, Spain. 11Infectious Diseases, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, UK. 12Infectious Diseases, Saint Pierre Hospital, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium. 13Infectious Diseases, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. 14Infectious Diseases, Universitatsklinikum, Essen, Germany. 15Infectious Diseases, University Hospital of Nantes, Nantes, France. 16Medicine, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

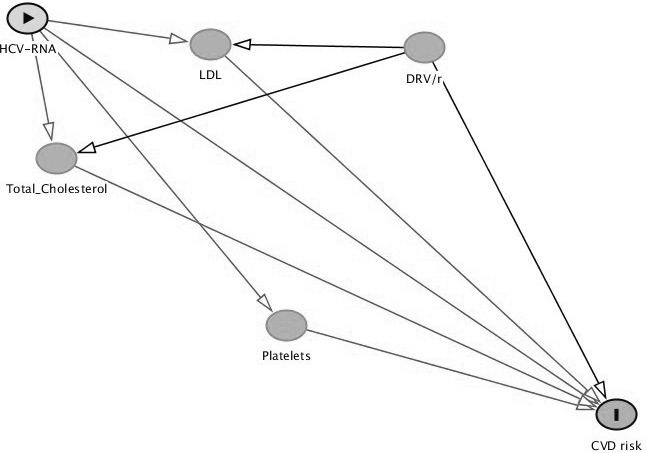

Background: Switching from ritonavir‐boosted protease inhibitors (PI/r) to dolutegravir (DTG) in subjects with a high cardiovascular risk resulted in a better lipid profile at 48 weeks than continuing PI/r. Whether this strategy may have an impact on biomarkers involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease in HIV‐infected subjects is unknown.

Materials and methods: Within a pre‐planned sub‐study, we assessed 48‐week changes in several biomarkers including serum high‐sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1), vascular adhesion molecule‐1 (VCAM‐1), selectin E and P, adiponectin, insulin, oxidised LDL, malondialdehyde, soluble CD14 (sCD14) and CD163 (sCD163), and cystatin C, and urine beta‐2 microglobulin. The median percent changes from baseline were compared with Mann‐Whitney test, and the association between the percent changes in biomarkers and lipid fractions or other variables of interest with Spearman correlation test. All p values were two‐sided with a significance level of 0.01 to account for the multiplicity of tests.

Results: Of 415 randomised patients, 313 (147 DTG, 166 PI/r) remained on their allocated therapy for 48 weeks and had samples available. We observed significant decreases in sCD14 (−11%, p < 0.001) and adiponectin (−11%, p < 0.001), and a trend to decrease in hsCRP (−13%, p = 0.069) and oxidised LDL (−13%, p = 0.084) in the DTG group relative to PI/r group. Percent change in sCD14 was inversely correlated with percent change in CD4 count (coefficient ‐0.113, p = 0.049). Median (IQR) CD4 cell (/mm3) change was +32 (‐66 to 109) in DTG arm and ‐6 (‐87 to 73) in PI/r arm (p = 0.049). Percent change in adiponectin was inversely correlated with percent change in body mass index (BMI) (coefficient ‐0.227, p < 0.001). Median (IQR) baseline BMI (kg/m2) was 25.7 (23.4 to 28.0) in DTG arm and 26.1 (23.5 to 28.2) in PI/r arm (p = 0.907). Median (IQR) BMI (kg/m2) change was +0.3 (‐0.4 to 1.1) in DTG arm and +0.2 (‐0.7 to 0.8) in PI/r arm (p = 0.121).

Conclusions: Switching from a PI/r‐containing to a DTG‐containing regimen in virologically suppressed HIV‐infected adults with a high cardiovascular risk decreased sCD14 but also adiponectin at 48 weeks. sCD14 and adiponectin reductions may have opposite decreasing [1] and increasing [2] cardiovascular effects in HIV‐infected subjects. Although the overall cardiovascular impact of the NEAT022 study switching strategy was positive [3], the decrease in adiponectin was associated with BMI gain and this sub‐study highlights the importance of further assessing the potential impact of DTG therapy on the mechanisms involved in body weight.

References

[1] Longenecker CT, Jiang Y, Orringer CE, Gilkeson RC, Debanne S, Funderburg NT, et al. Soluble CD14 is independently associated with coronary calcification and extent of subclinicalvascular disease in treated HIV infection. AIDS 2014;28:969‐77.

[2] Ketlogetswe KS, Post WS, Li X, Palella FJ Jr, Jacobson LP, Margolick JB, et al. Lower adiponectin is associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease among HIV‐infected men. AIDS 2014;28:901‐9.

[3] Gatell JM, Assoumou L, Moyle G, Waters L, Johnson M, Domingo P, et al. Switching from a ritonavir‐boosted protease inhibitor to a dolutegravir‐based regimen for maintenance of HIV viral suppression in patients with high cardiovascular risk. AIDS 2017;31:2503‐14.

O114

Risk of hospitalisation according to gender, sexuality and ethnicity among people with HIV in the modern ART era

S Rein1, F Lampe1, M Johnson2, C Chaloner1, F Burns1, S Madge2, A Phillips1, C Smith1

1Institute for Global Health, University College London, London, UK. 2HIV Medicine, Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust, London, UK

Background: There has been little research on the impact of gender and sexual orientation on hospitalisations in HIV‐positive people in the UK in the modern ART era.

Materials and methods: All HIV‐diagnosed individuals attending the Royal Free Hospital, London, from 2007 onwards were followed until 2016. Rates of all‐cause hospitalisation in the first year after diagnosis (analysis A) and from Year 1 onwards (analysis B) were calculated according to gender/sexuality/ethnicity and adjusted for demographic and clinical factors using Cox and Poisson regression respectively. Repeated hospitalisations were permitted in analysis B.

Results: For analysis A, 166 hospitalisations occurred in 1307 newly‐diagnosed individuals. Forty‐four percent, 55% and 46% of hospitalisations in MSM, men who have sex with women (MSW) and women were AIDS‐related. The higher hospitalisation rate in MSW and women compared to MSM was only partially explained by CD4 count and other factors (Table 1). Lower CD4, older age and earlier diagnosis date were independently associated with higher hospitalisation rate. For analysis B, 4211 individuals diagnosed for >1 year contributed 773 hospitalisations from 553 individuals. Seven percent, 18% and 10% of hospitalisations in MSM, MSW and women were AIDS‐related. Non‐Black MSW and women remained at higher risk of hospitalisation, but the association was weaker than that seen in the first year after diagnosis (Table 1). Lack of viral suppression, lower CD4, older age and earlier diagnosis date were also independently associated with hospitalisations.

Abstract O114 – Table 1. Association between gender / sexual orientation & ethnicity and all‐cause hospitalisation rate in HIV‐positive individuals in the first year after diagnosis (analysis A) and >1 year after diagnosis (analysis B)

| A: Hospitalisation in first year after diagnosis | B: Hospitalisations from one year after diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (PY) | Ratea | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | N (PY) | Ratea | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)c | |

| MSM | 655 (592) | 6.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2310 (15,013) | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black MSW | 138 (103) | 27.2 | 4.2 (2.5 to 6.8) | 2.4 (1.5 to 4.0) | 391 (2514) | 3.7 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) |

| Other ethnicity MSW | 169 (127) | 30.6 | 4.7 (3.0 to 7.5) | 3.2 (2.0 to 5.1) | 431 (2314) | 4.8 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.8) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2) |

| Black women | 245 (185) | 25.4 | 3.8 (2.5 to 5.9) | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.8) | 752 (4621) | 3.7 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Other ethnicity women | 100 (81) | 19.8 | 3.1 (1.7 to 5.6) | 2.3 (1.3 to 4.2) | 327 (2090) | 3.3 | 1.5 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) |

All p values <0.0001. aper 100 person‐years; adjusted for: bage, diagnosis year, 1st visit CD4; cage, current CD4, current CD4 nadir, current viral non‐suppression, time since diagnosis, previous AIDS. HR = hazard ratio; RR = rate ratio.

Conclusions: MSW and women have increased rate of hospitalisation in the modern ART era partially independent of clinical factors. Reasons for these variations in clinical outcomes should be investigated further to establish whether targeted interventions are needed.

O115

Multimorbidity and risk of death differs by gender in people living with HIV in the Netherlands: the ATHENA cohort study

F Wit1, M van der Valk2, J Gisolf3, W Bierman4, P Reiss2

1Stichting HIV Monitoring, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands. 2Department of Internal Medicine, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands. 3Department of Internal Medicine, Rijnstate Ziekenhuis, Arnhem, Netherlands. 4Department of Internal Medicine – Infectious Diseases, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

Background: PLWHIV on cART are living longer and because of ageing are experiencing more non‐AIDS comorbidities, which have become the most common cause of death in PLWHIV on cART. We investigated if multimorbidity predicts mortality in PLWHIV on cART and whether this differs by gender.

Materials and methods: We used data from PLWHIV from the ATHENA cohort collected from 2000 to 2016. Comorbidities identified were: cardiovascular disease; stroke; non‐AIDS malignancies, excluding non‐melanoma skin cancers and pre‐malignant cervical/anal lesions; moderate‐severe chronic kidney disease (eGFR <30 mL/min ≥6 months, Grade ≥G3b); diabetes mellitus; hypertension (use of antihypertensives or blood pressure ≥160/100 mmHg); obesity (BMI >30). Poisson regression compared mortality between genders adjusting for demographics, traditional risk factors and HIV‐related parameters.

Results: Data from 24,383 PLWHIV (19.2% females) were included (see Table 1). At cART initiation the mean number of non‐AIDS comorbidities in males (0.26) and females (0.25) were similar (p = 0.34). At last available follow‐up in 2016 the mean number of comorbidities had increased in both males (0.59) and females (0.59), p = 0.18. Mortality risk increased with number of comorbidities, from 6.83 deaths per 1000 person‐years in PLWHIV with zero comorbidities, to 13.8, 28.2, 65.6 and 139 per 1000 person‐years with 1, 2, 3, ≥4 comorbidities, respectively. Poisson regression confirmed the relationship between multimorbidity and mortality: risk ratio (RR) 2.66 (2.54 to 2.79) per additional comorbidity. Overall mortality risk, adjusted for the number of comorbidities, was significantly lower in women than men (RR 0.78 [0.67 to 0.91], p = 0.002). However, there was a significant interaction between gender, number of comorbidities and mortality (p < 0.0001) with the RR for women compared to men, ranging from 0.57 (0.45 to 0.74), to 0.75 (0.59 to 0.95), to 1.00 (0.74 to 1.38), to 1.52 (1.00 to 2.32), and 1.77 (0.83 to 3.78) for those with 0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4 comorbidities. Every individual comorbidity, except non‐AIDS malignancies, carried excess mortality risk for women. Excess mortality in women with more extensive multimorbidity was driven partly by exposure to mono‐ and dual nucleoside analogues before the cART era, as the increased risk attenuated and lost statistical significance after excluding PLWHIV pre‐treated with nucleoside analogues before start of cART: RR for women compared to men at three and four comorbidities were 1.39 (0.87 to 2.23) and 1.17 (0.47 to 2.91), respectively.

Abstract O115 – Table 1. All results are presented as percentages or as median (IQR)

| Females | Males | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at entry into the cohort | |||

| Number of participants | 4687 (19.2%) | 19,696 (80.8%) | ‐ |

| Age | 33.5 (27.7 to 40.9) | 39.3 (32.5 to 47.1) | <0.0001 |

| Dutch nationality | 27.1% | 63.1% | <0.0001 |

| Transmission category | <0.0001 | ||

| MSM | ‐ | 73.4% | |

| Heterosexual | 87.8% | 17.0% | |

| Injecting drug use | 4.2% | 2.7% | |

| Other | 8.0% | 6.9% | |

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | ||

| Never | 42.0% | 27.5% | |

| Current | 21.0% | 36.6% | |

| Past | 8.8% | 12.8% | |

| Missing | 28.3% | 23.1% | |

| Chronic HBV infection | 3.9% | 5.1% | 0.0003 |

| Chronic HCV infection | 7.1% | 5.2% | <0.0001 |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 310 (171 to 490) | 323 (200 to 482) | 0.0002 |

| Viral load (log10 copies/mL) | 3.6 (2.4 to 4.7) | 4.2 (2.6 to 5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Characteristics at start cART | |||

| Pre‐treated with nucleosides before start cART | 7.6% | 8.9% | 0.0002 |

| Years known HIV‐positive | 0.5 (0.2 to 3.2) | 0.8 (0.3 to 3.5) | <0.0001 |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 270 (150 to 410) | 290 (160 to 430) | <0.0001 |

| Duration of prior CD4 count <200 (years) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.23) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.21) | <0.0001 |

| Viral load (log10 copies/mL) | 4.1 (2.9 to 4.9) | 4.6 (3.5 to 5.1) | <0.0001 |

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | 14.3% | 14.5% | 0.76 |

Conclusions: Multimorbidity was a strong independent predictor of mortality in adult PLWHIV. Although women in general and especially women with less than three comorbidities had lower mortality than men, their risk was reversed and increased compared to men when experiencing three or more comorbidities.

O116

The economic burden of comorbidities among people living with HIV in Germany: a cohort analysis using health insurance claims data

E Wolf1, S Christensen2, H Diaz‐Cuervo3

1MUC Research, Munich, Germany. 2Infectious Diseases, Center for Interdisciplinary Medicine, Münster, Germany. 3HEOR, Gilead Sciences, London, UK

Background: Current treatment options for HIV increased life expectancy of PLWHIV. Therefore, management of non‐HIV related comorbidities became an essential part of HIV care. Although the clinical burden of comorbidities is well described in PLWHIV, data on the economic burden of comorbidities are limited. This analysis estimated the cost of acute and chronic non‐HIV related comorbidities by using a large health insurance claims database in Germany.

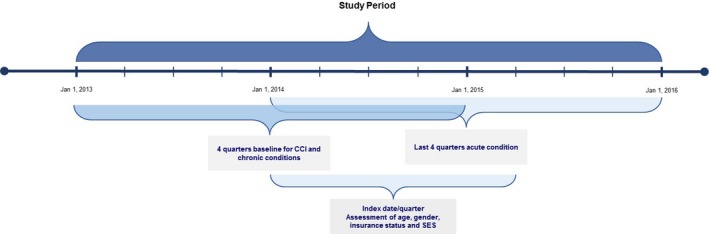

Materials and methods: The German InGef health insurance claims database was used to identify a cohort of adult patients with HIV diagnosis record within every calendar between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2014. HIV infection and comorbidities were detected using ICD‐10‐GM codes (see Figure 1 for evaluation periods). Total costs (Euro, €) including outpatient, inpatient, medication costs were evaluated during the last available 1‐year period before study end (31 December 2015), date of death or loss to follow‐up. A multivariable GLM regression model using log‐link function and gamma distribution was used to estimate the contribution of comorbidity to total healthcare costs excluding ART costs. The model included patient demographics, the clinical conditions used in Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), other chronic comorbidities not overlapping with CCI and acute comorbidities (i.e. acute/chronic cardiovascular disease excluding congestive heart failure, acute/chronic hepatitis B or C, alcohol abuse, bone fractures due to osteoporosis, dyslipidaemia and hypertension). The results of statistically significant estimators (using backward selection) are presented here.

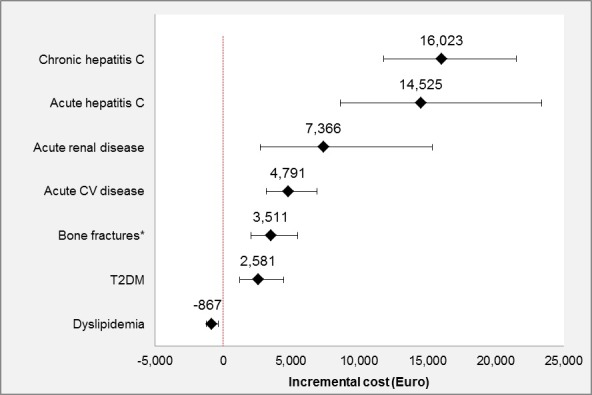

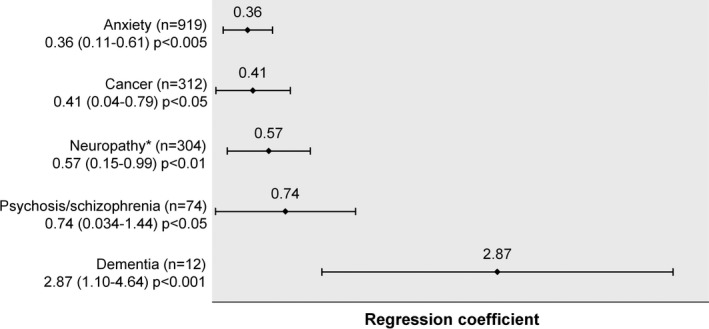

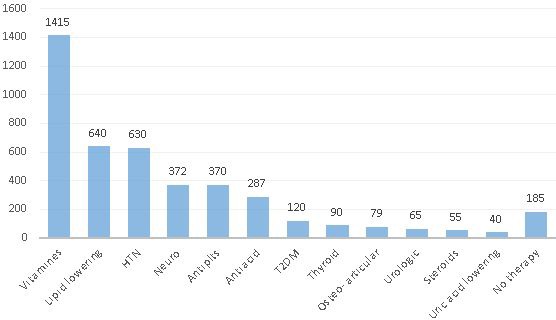

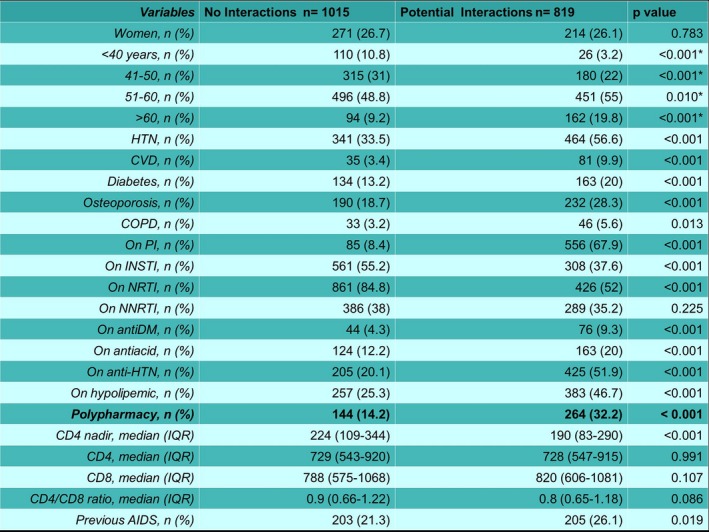

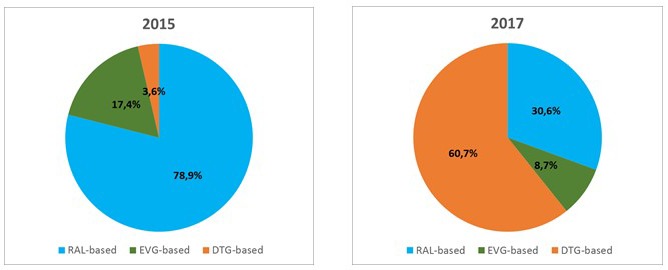

Results: Two thousand one hundred and five patients met eligibility criteria (82.6% male, median age 47.8 years, 41.6% >50 years). Average number of acute and chronic comorbidities was 0.3 (range 0 to 3) and 1 (range 0 to 6), respectively. Mean annual total healthcare costs including ART were 22,817€, excluding ART 7609€; mean inpatient costs were 1467€, mean outpatient costs were 1589€, mean medication costs excluding ART were 4196€, and mean ART costs were 14,232€. Estimated incremental annual costs were 4791€ for acute cardiovascular disease, 14,525€ for acute hepatitis C, 7366€ for acute renal disease, 3511€ for bone fractures due to osteoporosis, 16,023€ for chronic hepatitis C, 2581€ for diabetes mellitus type 2, ‐867€ for dyslipidaemia and ‐1678€ for being female (Table 1, Figure 2).

Abstract O116 – Figure 1. Evaluation periods. CCI = Charlson comorbidity index.

Abstract O116 – Figure 2. Incremental cost estimates of acute and chronic non‐HIV related comorbidities.

Abstract O116 – Table 1. Prevalence and incremental cost estimates for acute and chronic non‐HIV related comorbidities included in the final model

| Comorbidities | Prevalence | Incremental cost (€) | 95% CI of cost (€) (lower) | 95% CI of cost (€) (upper) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4766 | 4460 | 5093 | ||

| Gender, being female | 17.4% | ‐1,678 | ‐1929 | ‐1327 | <0.001 |

| Acute conditions | |||||

| Acute cardiovascular disease | 12.7% | 4791 | 3165 | 6884 | <0.001 |

| Acute hepatitis C | 2.4% | 14,525 | 8618 | 23,360 | <0.001 |

| Acute renal disease | 1.3% | 7366 | 2742 | 15,340 | <0.001 |

| Bone fractures due to osteoporosis | 9.0% | 3511 | 2020 | 5481 | <0.001 |

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| Chronic hepatitis C | 8.5% | 16,023 | 11,771 | 21,535 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 8.3% | 2581 | 1214 | 4421 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 23.5% | ‐867 | ‐1250 | ‐356 | 0.002 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 0.6% | 0.438 | |||

ART = antiretroviral treatment. Evaluation of the model appropriateness; AIC = 40,587, Box Cox λ = 0, Park test estimate = 2.24, scaled deviance/df =1.2.

Conclusions: This multivariable GLM regression model using claims data in Germany revealed the high economic impact of some comorbidities with estimated incremental annual costs ranging from 2581€ to 16,023€. These results support the importance of management of comorbidity in PLWHIV to decrease medical and economic burden.

O13 – Lock Lecture

O131

STIs among MSM: new challenges in prevention, diagnosis and treatment

J Molina

Department of Infectious Diseases and University of Paris 7, St Louis Hospital, Paris, France

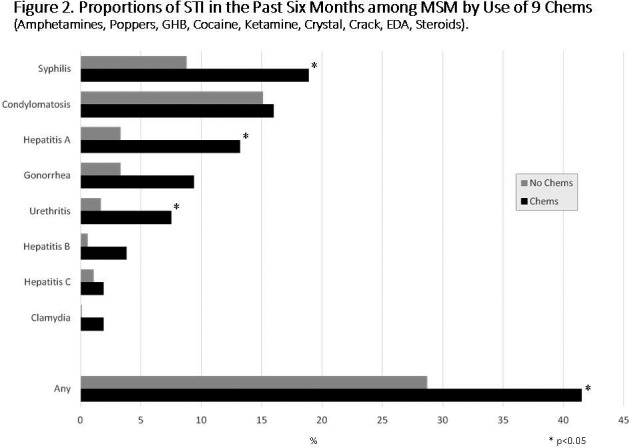

The incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), both bacterial (due to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrheae, Mycoplasma genitalium and Treponema pallidum) and viral (due to viral hepatitis A and C and human papillomaviruses), is increasing worldwide, especially in MSM, and represents a major public health concern. Indeed, the advances in the treatment and prevention of HIV infection over the last couple of years have led to an increase in risk compensation with less consistent use of condoms in this population. Although these high rates of STIs among MSM predated the implementation of oral PrEP and do not undermine its efficacy against HIV, they represent a new challenge in prevention, diagnosis and treatment. This review will first address the different approaches that could be proposed today to reduce the rate of STIs in a context of low condom use, and will include prospects for future strategies including antibiotic prophylaxis and vaccines for STIs. Also, most guidelines have updated their recommendations to encourage systematic testing for STIs every three months among MSM with high‐risk behaviour, and implementation of this recommendation combined with early treatment and partner notification should lead to a decrease in STI rates. The different diagnostic tools available and in development will be presented with a focus on point‐of‐care tests and tests that allow detection of antimicrobial resistance to guide treatment. Indeed, one of the main challenges with bacterial STIs is the increasing rate of antibiotic resistance, especially for gonorrhoea and Mycoplasma genitalium. National networks for surveillance of antimicrobial resistance need to be implemented and supported. Also, new antibiotics need to be developed to overcome the limitations of current treatment strategies. Altogether, there is a need to foster research in STIs to address all these challenges and meet the World Health Organization global targets for STIs in 2030, such as a 90% reduction of the global incidence of gonorrhoea and syphilis.

O14 – Drug Interactions, ARV Toxicity and Switching

O141

The top 10 DDIs in day‐to‐day clinical management of HIV

C Marzolini

Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Large surveys suggest that up to a quarter of HIV‐infected patients may be at risk of a clinically significant drug‐drug interaction (DDI) even with the latest antiretroviral treatments. Antiretroviral drugs are recognised to be amongst the therapeutic agents with the highest potential for DDIs as these drugs can be both a perpetrator and a victim of DDIs. Common mechanisms of DDIs with antiretroviral agents involve inhibition or induction of drug metabolism enzymes or drug transporters as well as chelation with divalent cations or pH‐dependent changes in drug absorption. DDIs can lead to drug toxicity or treatment failure of the antiretroviral drug and/or the co‐administered drug. DDIs are practically unavoidable in HIV care given the life‐long antiretroviral treatments and the growing prevalence of non‐HIV polypharmacy particularly in the context of an ageing HIV population. Thus, the identification, prevention and management of DDIs should remain a key priority in HIV care. The potential for DDIs needs to be considered systematically when selecting an antiretroviral regimen or when adding any new comedication to an existing HIV treatment with particular attention to adjust dosage or perform clinical monitoring when needed. In this regard, searchable online drug interactions databases constitute valuable tools to recognise and manage unwanted DDIs in clinical practice. In addition, educational programmes should be encouraged to improve awareness on the issue of DDIs and thereby prevent deleterious drug effects. This presentation will review the clinical management including mechanistic aspects of 10 selected clinically relevant DDIs between antiretroviral agents and non‐HIV drugs.

O142

Adverse effects of current ARVs: myths and realities

P Mallon

School of Medicine, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Advances in antiretroviral drug development have helped the majority of people living with HIV‐1 infection with access to current antiretroviral therapy (ART) to realise long‐term treatment goals of near‐normal life span with limited drug‐related toxicity. Often, discrimination between which ART to use, in both treatment initiation and switch, is based on knowledge of subclinical toxicities that may not necessarily have clinically meaningful impact for the individual. Examples of these toxicities include laboratory or imaging changes such as proteinuria and loss of bone density. Switch for potential subclinical toxicity carries with it a risk of unintentional introduction of new clinical problems, which for a particular individual may have important clinical consequences. Additionally, some new compounds may have toxicities that remain ill‐defined or are still emerging as they become more widely used in populations underrepresented in registration clinical trials. Understanding these nuances is central to the appropriate use of antiretrovirals in treatment of chronic HIV‐1 infection. This presentation will discuss common toxicities, provide evidence behind associations between toxicities and specific antiretrovirals and place these within a relevant clinical context to provide a framework for healthcare providers to consider the best regimen for an individual person living with HIV.

O143

Meta‐analysis of the risk of Grade 3/4 or serious clinical adverse events in 12 randomised trials of PrEP (n = 15,678)

V Pilkington1, A Hill2, S Hughes3, N Nkwolo4, A Pozniak4

1Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK. 2Department of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. 3Research, Metavirology Ltd, London, UK. 4Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Background: TDF/FTC used as pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has proven benefits in preventing HIV infection. Generic formulations of TDF/FTC are available for <$60 per person‐year in low‐income countries. Widespread use of TDF/FTC can only be justified if the preventative benefits outweigh potential risks of adverse events. A previous meta‐analysis of TDF/FTC compared to alternative TAF/FTC for treatment found no significant difference in safety endpoints [1], but more evidence around the safety of TDF/FTC is needed to address concerns and inform widespread use.

Methods: A systematic review identified 13 randomised trials of PrEP, using either TDF/FTC or TDF, versus placebo or no treatment: VOICES, PROUD, IPERGAY, FEM‐PrEP, TDF‐2, iPREX, IAVI Kenya, IAVI Uganda, PrEPare, PARTNERS, US Safety study, Bangkok TDF study, W African TDF study. The number of participants with Grade 3/4 adverse events or serious adverse events (SAEs) was compared between treatment and control in meta‐analysis. Further analyses of specific renal and bone markers were also undertaken, with fractures as a marker of bone effects and creatinine elevations as a surrogate marker for renal impairment. Analyses were stratified by study duration (one year of follow‐up).

Results: The 13 randomised trials included 15,678 participants in relevant treatment and control arms. Three studies assessed TDF use only. The number of participants with Grade 3/4 adverse events was 1305/7504 (17.4%) on treatment versus 1259/7502 (16.8%) on control (difference 0%, 95% CI ‐1% to +2%). The number of participants with SAEs was 738/7843 (9.4%) on treatment versus 795/7835 (10.1%) on no treatment (difference 0%, 95% CI ‐1% to +1). Similarly, adverse renal and bone outcomes did not occur significantly more often in participants taking PrEP versus control regimens (difference 0%, 95% CI 0% to 0%). There was no difference in outcome between studies with <1 versus >1 year of randomised treatment.

Conclusions: In this meta‐analysis of 13 randomised clinical trials of PrEP in 15,678 participants, there was no significant difference in risk of Grade 3/4 clinical adverse events or SAEs between TDF/FTC (or TDF) and control (Table 1). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in risk of specific renal or bone adverse outcomes. The safety profile of TDF/FTC would support more widespread use of PrEP in populations with a lower risk of HIV infection.

Abstract O143 – Table 1. Results of the meta‐analyses of overall risk difference between treatment and control study arms for each outcome of interest

| Outcome | Events (PrEP) | Total participants (PrEP) | Events (control) | Total participants (control) | Risk difference (95% CI) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3/4 adverse events | 1305 | 7504 | 1259 | 7502 | 0% (‐1% to 2%) | p = 0.56 |

| Serious adverse events | 738 | 7843 | 795 | 7835 | 0% (‐1% to 1%) | p = 0.74 |

| Renal (creatinine elevations) | 11 | 7620 | 5 | 7622 | 0% (0%‐0%) | p = 0.38 |

| Bone (fractures) | 202 | 5588 | 184 | 5596 | 0% (0%‐0%) | p = 0.69 |

Reference: [1] Hill A, Hughes SL, Gotham D, Pozniak AL. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: is there a true difference in efficacy and safety? J Virus Erad. 2018;4:72‐9.

O144

Dual therapy with PI/r+3TC or PI/r+TDF shows non‐inferior HIV RNA suppression and lower rates of discontinuation for adverse events, versus triple therapy. Meta‐analysis of seven randomised trials in 1624 patients

Z Liew1, A Hill2, B Simmons1

1Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK. 2Department of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Background: Using fewer nucleos(t)ide analogues could improve safety, increase adherence and lower treatment costs. Generic versions of lamivudine (3TC), tenofovir (TDF), atazanavir/r (ATVr), darunavir/r (DRV/r) and lopinavir/r (LPV/r) are becoming available worldwide. Several randomised trials have evaluated two drug combinations of a ritonavir‐boosted protease inhibitor (PI/r) in combination with 3TC or TDF in naive patients or those with HIV RNA suppression at baseline.

Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, conference proceedings and trial registries was conducted to identify all randomised controlled trials comparing PI/r+3TC or PI/r+TDF dual therapy to triple therapy in treatment‐naïve and treatment‐experienced, suppressed patients. Using inverse‐variance weighting, pooled risk differences (RD) were calculated for virological suppression (FDA Snapshot), protocol‐defined virological failure, treatment‐emergent resistance and discontinuation due to adverse events. Virological suppression was assessed for non‐inferiority (FDA non‐inferiority margin delta=‐4%).

Results: Seven studies were identified of three different ritonavir‐boosted PIs in 1624 patients, three treatment naïve (ANDES n = 145, GARDEL n = 306, Kalead n = 152) and four treatment experienced (ATLAS n = 236, DUAL n = 249, OLE n = 239, SALT n = 267). The pooled risk difference for viral suppression at 48 weeks of dual therapy compared to triple therapy was +2% (95% CI ‐2% to +6%) which met the FDA criteria for non‐inferiority. Results were consistent in treatment‐naïve and switching studies (p = 0.94). There were 5/822 patients on dual therapy with treatment‐emergent primary IAS NRTI drug resistance mutations, versus 5/802 on triple therapy (p = 0.98) (Table 1). Treatment discontinuation for adverse events was significantly lower for dual therapy at Week 48 (RD ‐2.6%, 95% CI ‐4.2 to ‐0.9%, p = 0.002).

Conclusions: In this meta‐analysis of seven randomised trials in 1624 patients, rates of HIV RNA suppression <50 copies/mL at Week 48 on PI/r+3TC or PI/r+TDF dual therapy were non‐inferior to triple therapy by US FDA criteria, with significantly fewer discontinuations for adverse events. Consistent results were seen in treatment‐naive and suppressed patients. There was no increased risk of treatment‐emergent drug resistance for dual therapy. Combination treatment with DRV/r+3TC costs <$500 per person‐year in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Generic combinations of DRV/r+3TC could save significant costs relative to branded TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC, with potential improvements in safety.

Abstract O144 – Table 1. Meta‐analysis of dual therapy trials

| Endpoint | Dual therapy | Triple therapy | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV RNA <50 copies/mL FDA Snapshot | 686/822 (83.5%) | 644/802 (80.3%) | +2% (‐2% to +4%) |

| Protocol‐defined virological failure | 41/822 (5.0%) | 36/802 (4.5%) | 0% (‐2% to +2%) |

| Treatment‐emergent drug resistance | 5/822 (0.6%) | 5/802 (0.6%) | 0% (‐1% to +1%) |

Country of research: United Kingdom. Key population: People living with HIV.

O145

No significant changes to residual viremia after switch to dolutegravir and lamivudine in a randomized trial

J Li1, P Sax1, V Marconi2, J Fajnzylber1, B Berzins3, A Nyaku4, C Fichtenbaum5, T Wilkin6, C Benson7, S Koletar8, R Lorenzo‐Redondo3, B Taiwo3

1Infectious Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA. 2Infectious Diseases, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA. 3Infectious Diseases, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA. 4Infectious Diseases, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ, USA. 5Internal Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA. 6Infectious Diseases, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA. 7Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA. 8Infectious Diseases, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

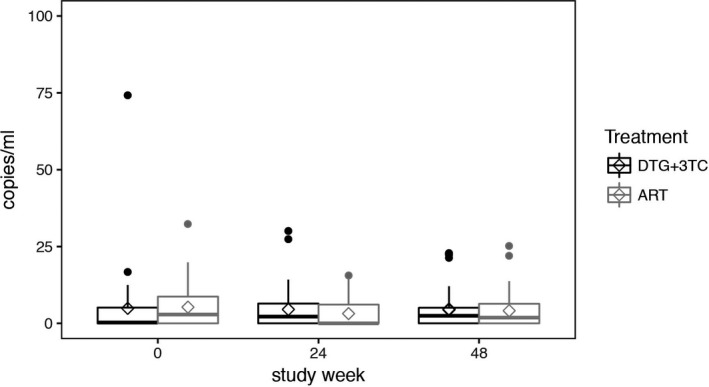

Background: The Antiretroviral Strategy to Promote Improvement and Reduce Exposure (ASPIRE) study was a randomized, 48‐week, controlled trial for participants who were virologically suppressed on a standard three‐drug antiretroviral regimen (ART) and maintained viral suppression by commercial viral load testing after switching to dolutegravir and lamivudine (DTG+3TC) [1]. We assessed levels of residual viremia by an ultrasensitive viral load assay to determine whether DTG+3TC resulted in increased low‐level viral replication.

Materials and methods: The integrase single‐copy assay (iSCA, limit of detection 0.5 HIV‐1 RNA copies/mL) was performed on plasma from study entry, Week 24 and Week 48 after randomization to DTG+3TC versus continued three‐drug ART. Differences in residual viremia between the treatment arms were analyzed by fitting a linear model accounting for possible within‐patient correlation using a generalized least square fit. We included the study time point and treatment arm in the model. Participants who discontinued ART during the study were excluded from this analysis.

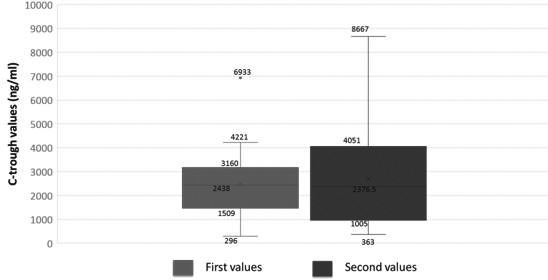

Results: Of the 89 participants randomized in the ASPIRE study, seven discontinued their randomized ART due to virologic rebound (N = 2), adverse events (N = 1) or noncompliance (N = 4). A total of 82 participants were included in the current analysis (41 from each arm). The 82 participants were 88% male, 61% white and had a median age of 48 years with a median CD4 count of 677 cells/mm3. Prior ART exposure (median 5.8 years) consisted of integrase inhibitors (40%), non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (30%) and protease inhibitor‐based regimens (29%) at the time of study entry. At baseline, mean residual viremia in the DTG+3TC versus three‐drug ART arms (4.9 vs. 5.3 copies/mL HIV‐1 RNA copies/mL, Figure 1) did not differ significantly (difference = ‐0.5 copies/mL, 95% CI ‐3.8 to 2.8, p = 0.78). After randomization, the differences in residual viremia, between the DTG+3TC versus three‐drug ART arms, adjusting for the baseline values, were not statistically significant (at Week 24: 1.3 copies/mL, 95% CI ‐2.1 to 4.7, p = 0.45; and at Week 48: 0.5 copies/mL, 95% CI ‐2.9 to 3.9, p = 0.77).

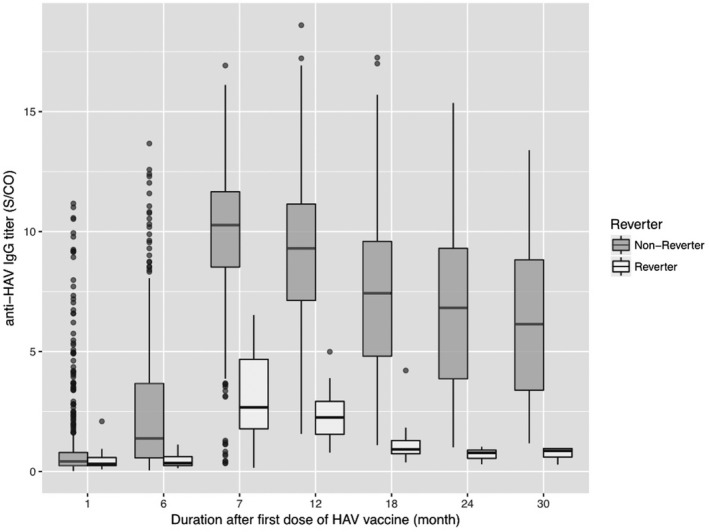

Abstract O145 – Figure 1. Levels of HIV viral load (copies/mL) by the ultrasensitive integrase single‐copy assay by treatment arm at baseline, 24 and 48 weeks after ART switch. ART specifies participants who maintained their three‐drug ART regimen. Tukey's box‐and‐whisker plots, box limits: interquartile range (IQR); middle line: median; diamond: mean; vertical lines: adjacent values (1st quartile −1.5 IQR; 3rd quartile +1.5 IQR); dots: outliers.

Conclusions: In this randomized trial, we found no evidence for increased viral replication after a switch to DTG+3TC as reflected by stable levels of residual viremia. These results support further investigation of DTG+3TC dual therapy.

Reference: [1] Taiwo BO, Marconi VC, Berzins B, Moser CB, Nyaku AN, Fichtenbaum CJ, et al. Dolutegravir plus lamivudine maintain HIV‐1 suppression through week 48 in a pilot randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1794‐7.

O21 – Approaches to Treatment and Cure

O211

Phase III randomized, controlled clinical trial of bictegravir coformulated with FTC/TAF in a fixed‐dose combination (B/F/TAF) versus dolutegravir (DTG) + F/TAF in treatment‐naïve HIV‐1 positive adults: Week 96

H Stellbrink1, J Arribas2, J Stephens3, H Albrecht4, P Sax5, F Maggiolo6, C Creticos7, C Martorell8, X Wei9, K White10, S Collins11, A Cheng11, H Martin11

1ICH Study Center, Hamburg, Germany. 2Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain. 3Department of Internal Medicine, Mercer University School of Medicine, Macon, GA, USA. 4Palmetto Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA. 5Division of Infectious Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA. 6Infectious Diseases, Azienda Ospedaliera Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy. 7Infectious Diseases, Howard Brown Health Center, Chicago, IL, USA. 8Infectious Diseases, The Research Institute, Springfield, MA, USA. 9Biometrics, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA. 10Clinical Virology, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA. 11HIV Clinical Research, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA

Background: Bictegravir (B), a novel, potent integrase strand transfer inhibitor with a high barrier to resistance, is coformulated with emtricitabine (F) and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) as the European Medicine Agency‐approved single‐tablet regimen, B/F/TAF. We report Week (W) 96 secondary endpoint results from an ongoing, double‐blind, Phase III study directly comparing B with dolutegravir (DTG), each given with F/TAF in treatment‐naïve, HIV‐infected adults. Both treatments demonstrated high efficacy with no viral resistance and were well tolerated through W48.

Methods: Six hundred and forty‐five treatment‐naive adults living with HIV‐1 and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min were randomized 1:1 to receive blinded treatment with B/F/TAF (50/200/25 mg) or DTG (50 mg) + F/TAF (200/25 mg) with matching placebos once daily. Chronic hepatitis B and/or C infection was allowed. Primary endpoint was proportion of participants with HIV‐1 RNA <50 copies/mL (c/mL) at W48 (FDA Snapshot); same measure of efficacy was evaluated as a secondary endpoint at W96. Noninferiority for the secondary endpoint was assessed through 95% CIs using a 12% margin. Secondary endpoints were safety measures (adverse events [AEs], laboratory results).

Results: At W96, 84.1% (269 of 320) on B/F/TAF and 86.5% (281 of 325) on DTG+F/TAF had HIV‐1 RNA <50 c/mL (difference ‐2.3%; 95% CI ‐7.9% to 3.2%, p = 0.41). Number of participants with HIV‐1 RNA ≥50 c/mL at W96 was 0 for B/F/TAF and 5 (1.5%) for DTG+F/TAF. In the per‐protocol analysis, 100% of participants on B/F/TAF had HIV‐1 RNA <50 c/mL versus 98.2% on DTG+F/TAF (p = 0.03). Through W96, no participant had emergent resistance to study drugs. AEs led to discontinuation in six (2%) B/F/TAF versus five (2%) DTG+F/TAF (one [B/F/TAF] and four [DTG+F/TAF] after W48). Most common AEs overall were diarrhea (18% B/F/TAF, 16% DTG+F/TAF) and headache (16% B/F/TAF, 15% DTG+F/TAF). Treatment‐related AEs were reported for 20% B/F/TAF versus 28% DTG+F/TAF (p = 0.02). Lipid changes were not significantly different between groups. No renal discontinuations and no cases of proximal renal tubulopathy were reported.

Conclusions: After 96 weeks, B/F/TAF achieved virologic suppression in 84.1% of treatment‐naïve adults with no treatment‐emergent resistance, and 100% had HIV‐1 RNA <50 c/mL in the per‐protocol analysis. B/F/TAF was safe and well tolerated with fewer treatment‐related AEs compared to DTG+F/TAF.

O212

Efficacy and safety of the once‐daily, darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (D/C/F/TAF) single‐tablet regimen (STR) in ART‐naïve, HIV‐1‐infected adults: AMBER Week 96 results

C Orkin1, J Eron2, J Rockstroh3, D Podzamczer4, S Esser5, L Vandekerckhove6, E Van Landuyt7, E Lathouwers7, V Hufkens7, J Jezorwski7, M Opsomer7

1Barts Health NHS Trust and Queen Mary University of London, London, UK. 2School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. 3HIV Outpatient Clinic, Universitätsklinikum Bonn, Bonn, Germany. 4L'Hospitalet, IDIBELL‐Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Barcelona, Spain. 5Dermatology und Venerology, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany. 6Ghent University and Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium. 7Janssen, Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium

Background: The once‐daily STR D/C/F/TAF 800/150/200/10 mg is approved in the EU and under regulatory review in the US. In AMBER (NCT02431247), D/C/F/TAF was non‐inferior versus D/C+F/TDF (control) (Week 48 VL <50 copies/mL: 91% vs. 88%, respectively; FDA Snapshot), with improved bone and renal biomarker safety, in ART‐naïve, HIV‐1‐infected adults. Week 96 analysis of efficacy, safety and resistance results are presented.

Methods: AMBER is a Phase III, randomised, active‐controlled, double‐blind, international, multicentre, non‐inferiority trial. ART‐naïve, HIV‐1‐infected adults were randomised (1:1) to D/C/F/TAF or D/C+F/TDF over at least 48 weeks. After unblinding, patients randomised to D/C/F/TAF continued on open‐label D/C/F/TAF and patients randomised to control were switched to D/C/F/TAF in the extension phase until Week 96.

Results: Seven hundred and twenty‐five patients were randomised and treated (at baseline 18% VL ≥100,000 copies/mL; median CD4+ count 453 cells/mm3). At Week 96, exposure to D/C/F/TAF was 626 patient‐years in the D/C/F/TAF arm, and consecutively 512 to D/C+F/TDF and 109 to D/C/F/TAF in the control arm. A high proportion of patients in the D/C/F/TAF arm (85%, 308/362) had virological suppression at Week 96 (VL <50 copies/mL; FDA Snapshot). A high Week 96 response rate (from baseline) was also observed in the control arm (84%, 304/363). VL ≥50 copies/mL (VF category by FDA Snapshot) at Week 96 occurred in 20/362 (6%) patients in the D/C/F/TAF arm and 16/363 (4%) from baseline in the control arm. Increases from baseline to Week 96 in CD4+ count (LS means, NC=F) were 229 cells/mm3 (D/C/F/TAF) and 227 cells/mm3 (control). No darunavir, primary PI or tenofovir RAMs were seen post‐baseline. In one patient in each arm an M184I and/or V RAM was detected (D/C/F/TAF arm Week 36; control arm Week 84). Few serious adverse events (SAEs) and AE‐related discontinuations and no deaths occurred (Table 1). Improvements in renal and bone parameters were maintained in the D/C/F/TAF arm and seen in the control arm after switch, with a small change in TC/HDL‐C ratio (Table 1).

Abstract O212 – Table 1. Treatment‐emergent AEs and changes in renal, lipid and bone parameters at Week 96

| D/C/F/TAF arm | Control arm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment‐emergent AEs, n (%) | D/C/F/TAF (baseline — Week 48) N = 362 | D/C/F/TAF (Week 48 — Week 96) N = 335 | D/C/F/TAF (baseline — Week 96) N = 362 | p‐valuea , >b | D/C+F/TDF (baseline — switch) N = 363 | D/C/F/TAF (switch— Week 96)c N = 295 | p‐valuea,b |

| Patient‐years exposure | 323 | 303 | 626 | 512 | 109 | ||

| AEs, any grade | 312 (86) | 246 (73) | 334 (92) | ND | 326 (90) | 125 (42) | ND |

| Grade 3–4 AEs | 20 (6) | 29 (9) | 45 (12) | ND | 33 (9) | 15 (5) | ND |

| Serious AEs | 17 (5) | 24 (7) | 39 (11) | ND | 36 (10) | 8 (3) | ND |

| AE‐related discontinuations | 8 (2) | 2 (1) | 10 (3) | ND | 17 (5) | 1 (0.3) | ND |

| Median change in eGFR | |||||||

| eGFRcyst, mL/min/1.73 m2 | +4.0 | ND | +4.4 | 0.007 | +1.6 | 0.0 | 0.130 |

| eGFRcr, mL/min/1.73 m2 | ‐5.5 | ND | ‐5.6 | 0.001 | ‐8.0 | +2.3 | 0.001 |

| Median changes in renal biomarkers | |||||||

| UPCR (mg/g) | ‐15.7 | ND | ‐15.5 | 0.001 | ‐10.5 | ‐1.4 | 0.112 |

| UACR (mg/g) | ‐0.6 | ND | ‐0.7 | 0.001 | ‐0.2 | ‐0.5 | 0.001 |

| RBP:Cr (µg/g) | +6.9 | ND | +13.7 | 0.001 | +35.1 | ‐35.5 | 0.001 |

| B2M:Cr (µg/g) | ‐30.4 | ND | ‐27.0 | 0.001 | +18.4 | ‐40.5 | 0.001 |

| Median change in fasting lipids | |||||||

| TC (mg/dL) | +28.6 | ND | +34.0 | 0.001 | +10.4 | +21.8 | 0.001 |

| HDL‐C (mg/dL) | +4.4 | ND | +5.0 | 0.001 | +1.5 | +1.9 | 0.001 |

| LDL‐C (mg/dL) | +17.4 | ND | +21.7 | 0.001 | +5.0 | +15.1 | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL | +24.4 | ND | +29.2 | 0.001 | +14.2 | +14.2 | 0.001 |

| TC/HDL‐C ratio | +0.20 | ND | +0.25 | 0.001 | +0.08 | +0.24 | 0.001 |

| Change in BMD | N = 113 | N = 113 | N = 99 | N = 83 | |||

| Lumbar spine | |||||||

| Mean % change | ‐0.7 | ND | ‐0.9 | 0.039 | ‐2.6 | +0.5 | 0.223 |

| Increase by ≥3% | 12% | ND | 16% | ND | 5% | 18% | ND |

| Decrease by ≥3% | 27% | ND | 34% | ND | 43% | 10% | ND |

| Total hip | |||||||

| Mean % change | +0.1 | ND | ‐0.3 | 0.473 | ‐2.8 | +0.5 | 0.160 |

| Increase by ≥3% | 12% | ND | 17% | ND | 2% | 18% | ND |

| Decrease by ≥3% | 13% | ND | 23% | ND | 48% | 11% | ND |

| Femoral neck | |||||||

| Mean % change | ‐0.3 | ND | ‐1.3 | 0.005 | ‐3.1 | +0.2 | 0.660 |

| Increase by ≥3% | 14% | ND | 11% | ND | 5% | 21% | ND |

| Decrease by ≥3% | 23% | ND | 30% | ND | 58% | 17% | ND |

awithin treatment arm comparisons for change at Week 96 from reference assessed by: Wilcoxon signed‐rank test (eGFR, renal biomarkers and fasting lipids) and paired t‐test (BMD).

breference for the D/C/F/TAF arm is study baseline and for the control arm is the last value before the switch.

crespectively 2.5%, 41.3%, 36.4% of patients randomised to the control arm switched to D/C/F/TAF at Week 60, Week 72 and Week 84.

eGFRcyst = eGFR based on serum cystatin C (CKD‐EPI formula); eGFRcr = eGFR based on serum creatinine (CKD‐EPI formula); UPCR = urine protein: creatinine ratio; UACR = urine albumin: creatinine ratio; RBP:Cr = urine retinol binding protein: creatinine ratio; B2M:Cr = urine beta‐2‐microglobulin: creatinine ratio; TC = total cholesterol; HDL‐C = high density lipoprotein‐cholesterol; LDL‐C = low density lipoprotein‐cholesterol; BMD = bone mineral density; ND = not determined.

Conclusions: High virological response and low failure rates were seen at Week 96 in both arms, with no development of resistance to darunavir or TAF. FoR D/C/F/TAF, safety findings at Week 96 were consistent with those at Week 48. Bone, renal and lipid safety were consistent with known TAF and cobicistat profiles. In the control arm, safety findings were consistent with those in the D/C/F/TAF arm. D/C/F/TAF combines the efficacy and high genetic barrier to resistance of darunavir with the safety benefits of TAF for ART‐naïve, HIV‐1‐infected patients.

O213

Comparable viral decay with dolutegravir plus lamivudine versus dolutegravir‐based triple therapy

J Gillman1, P Janulis2, R Gulick3, C Wallis4, B Berzins2, R Bedimo5, K Smith6, M Aboud6, B Taiwo2

1Prism Health North Texas, Dallas, TX, USA. 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA. 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA. 4BARC South Africa and Lancet Laboratories, Johannesburg, South Africa. 5Infectious Diseases Section, VA North Texas Health Care System, Dallas, TX, USA. 6ViiV Healthcare, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

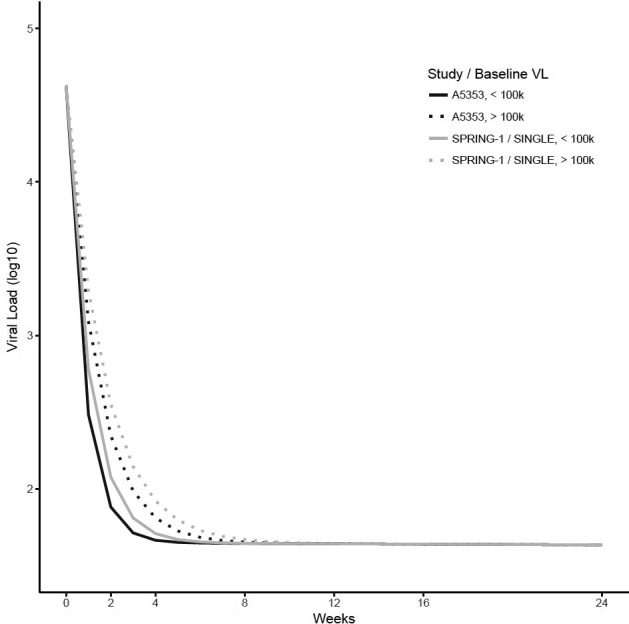

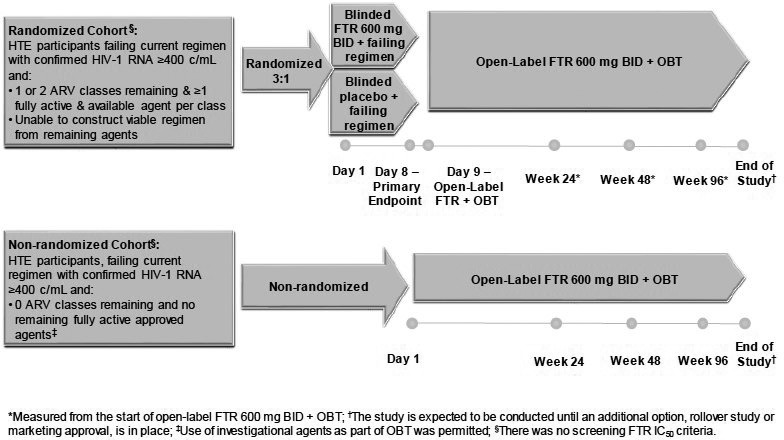

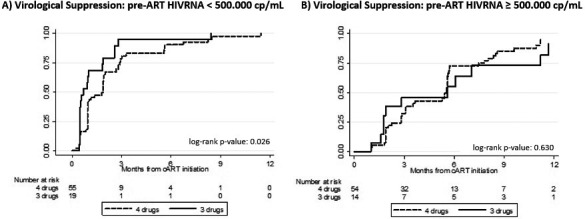

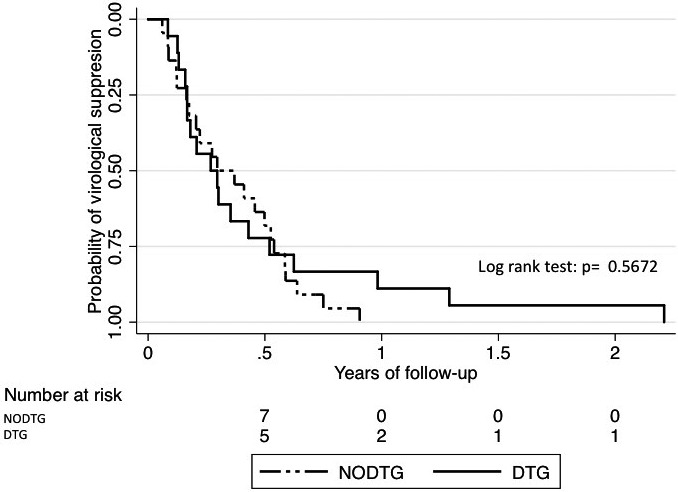

Background: The GEMINI studies demonstrated non‐inferiority of dolutegravir (DTG) plus lamivudine (3TC) compared to DTG plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) in treatment‐naïve HIV‐1 infected individuals with pre‐treatment plasma HIV‐1 RNA (viral load, VL) 1000 to 500,000 copies/mL. However, rapidity of viral suppression with DTG plus 3TC, which may influence the risk of viral transmission or selection of resistant variants, has not been studied adequately, particularly at higher pre‐treatment VL. A substudy of the PADDLE trial showed comparable viral decay between DTG plus 3TC and DTG‐based three‐drug therapy in participants with pre‐treatment VL <100,000 copies/mL. Viral decay in A5353, a pilot study of DTG plus 3TC where 30% of participants had pre‐treatment VL of 100,000 to 500,000 copies/mL, was determined in comparison to the decay in the DTG (50 mg) plus two nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors arms of the SPRING‐1 and SINGLE studies.

Materials and methods: Change in VL from baseline (pre‐treatment) was calculated for time points shared by A5353 (N = 120), SPRING‐1 (N = 51) and SINGLE (N = 417), i.e. study entry (Week 0), and Weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24. Ninety‐five percent confidence intervals of change from baseline for each observed week, using the log10 transformed VL, were examined and compared across the two‐drug and three‐drug therapy groups using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for non‐inferiority (δ = 0.5). For the viral decay analysis, we examined a bi‐exponential non‐linear mixed effect model. Three variables were added as covariates of the initial and secondary decay parameters: two‐drug versus three‐drug therapy, baseline VL (≤ vs. > 100,000 copies/mL) and an interaction term of the drug therapy and baseline VL stratum.

Results: The VL change from baseline with two‐drug therapy was non‐inferior to three‐drug therapy (p < 0.001). In the decay model (Figure 1), two‐drug therapy was associated with a faster initial decay rate compared to three‐drug therapy. Baseline VL greater than 100,000 copies/mL was associated with a slower initial decay rate. The faster initial decay rate with two‐drug therapy is partially offset when baseline VL is greater than 100,000 copies/mL as indicated by a significant interaction between baseline VL and drug therapy, resulting in simple slope decay rates as shown below. The later decay rate was non‐significantly different from zero, with no significant associations.

Abstract O213 – Figure 1. Simple slope decay rates.

Two‐drug – baseline VL <100,000 copies/mL = 1.272; two‐drug – baseline VL >100,000 copies/mL = 0.725; three‐drug – baseline VL <100,000 copies/mL = 0.969; three‐drug – baseline VL >100,000 copies/mL = 0.596.

Conclusions: Viral decay with the two‐drug regimen of DTG plus 3TC is comparable to the viral decay with DTG‐based triple therapy, even in individuals with higher pre‐treatment VL up to 500,000 copies/mL.

O214

The impact of M184V/I mutation on the efficacy of abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir regimens prescribed in treatment‐experienced patients

F Olearo1, H Nguyen2, F Bonnet3, G Wandeler4, M Stoeckle5, V Bättig5, M Cavassini6, A Scherrer7, P Schmid8, H Bucher9, H Günthard7, J Böni10, S Yerly11, A D'Armino Monforte12, M Zazzi13, P Bellerive14, B Rijnders15, P Reiss16, F Wit16, R Kouyos17, A Calmy18

1Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. 2Epidemiology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. 3Infectious Diseases Department, University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France. 4Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospital of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 5Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospital of Basel, Basel, Switzerland. 6Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. 7Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospital of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. 8Infectious Diseases Department, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 9Epidemiology, Basel University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland. 10Virology, Infectious Diseases Department, Zurich, Switzerland. 11Virology, University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. 12Infectious Diseases Department, Azienda Ospedaliera‐Polo Universitario San Paolo, Milan, Italy. 13Molecular Biology, University of Siena, Siena, Italy. 14Virology, University Hospital of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France. 15Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospital Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands. 16Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. 17Infectious Diseases Department and Epidemiology, University Hospital of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. 18Infectious Diseases Department, University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

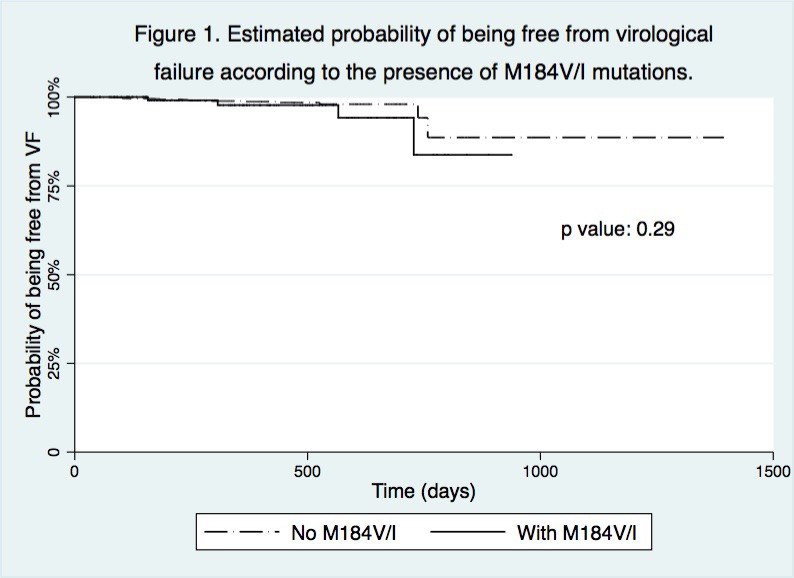

Background: The impact of archived resistance mutation M184V/I on virological success remains unclear in treatment‐experienced patients switching to the fixed dose combination abacavir (ABC)/lamivudine (3TC)/dolutegravir (DTG). Considering the possible role of this mutation in impairing the efficacy of both ABC and 3TC, we aimed to determine its impact on the virological failure (VF) rate in patients with suppressed viraemia on cART switching to an ABC/3TC/DTG regimen.

Materials and methods: This prospective study included treatment‐experienced adults from five European HIV cohorts (ARCA, Aquitaine, ATHENA, ICONA and SHCS) who switched to ABC/3TC/DTG between 2012 and 2016, with ≤50 copies/mL of HIV‐RNA at the time of switch and at least one pre‐existing genotypic resistance test from plasma (when drug‐naïve or during previous treatment failure). The primary outcome was the time to first VF (defined as two consecutive HIV‐RNA measurements >50 copies/mL or one HIV‐RNA measurement >50 copies/mL accompanied by a change in ART). We further considered a composite outcome considering the presence of VF or virological blips, defined as an isolated detectable HIV‐RNA >50 copies/mL followed by a return to virological suppression. A secondary outcome was discontinuation due to adverse events. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to quantify the effect of the M184V/I on outcomes.

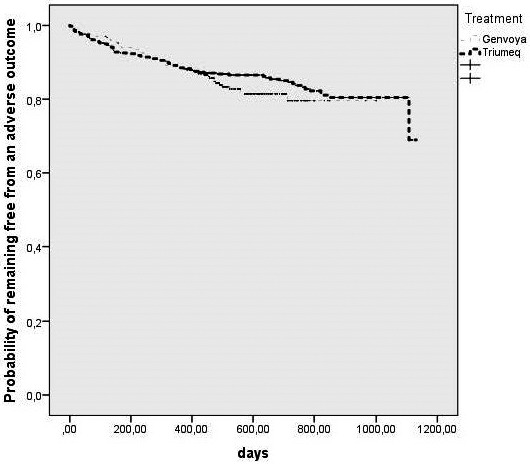

Results: One thousand six hundred and twenty‐six patients were included in the analysis (median follow‐up 289 days; IQR 154 to 441). Patients with archived M184V/I (n = 137) were older, more likely to have a history of previous injection drug use and with a longer duration of virological suppression before the switch. The VF rate was 15.1 per 1000 person‐years (95% CI 9.9 to 23.2) and higher in patients harbouring an archived M184V/I mutation, although not statistically significant (29.80 [11.17 to 79.39] vs. 13.56 [8.43 to 21.83]; p = 0.093) (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the estimated probability of being free from VF according to the presence of M184V/I mutations. In the multivariable model, M184I/V was not associated with VF (adjustment for VL zenith) or the composite endpoint (HR 3.03, CI 0.84 to 10.82; HR 2.22, CI 0.8 to 5.6, respectively). There were no differences in treatment discontinuation for reasons other than VF between patients with and without documented M184V/I (10.22% vs. 15.58%, respectively; p = 0.12).

Abstract O214 – Figure 1. Estimated probability of being free from virological failure according to the presence of M184V/I mutations.

Abstract O214 – Table 1. Virological primary outcomes

| Without M184V/I, N = 1489 (%) | With M184 V/I, N = 137 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Virological failure (VF) | 17 (1.14) | 4 (3) |

| a) 1st definition: 2x HIV‐RNA >50 copies/mL | 10 (0.67) | 1 (0.73) |

| b) 2nd definition: 1x HIV‐RNA >50 copies/mL + ABC/3TC/DTG stop | 7 (0.47) | 3 (2.1) |

| Treatment (ABC/3TC/DTG) discontinued for reasons other than VF | 232 (15.58) | 14 (10.22) |

| Virological blipsa (VB) had at least one blip during ABC/3TC/DTG | 63 (4.2) | 12 (8.8) |

| VB, median copies/mL (IQR) | 79 (62 to 122) | 72 (58 to 154) |

| VF incidence (per 1000 person‐years) | 13.56 (8.43 to 21.83) | 29.8 (11.17 to 79.39) |

avirological blips: any viral load measurement >50 copies/mL, with viral load subsequently undetectable.

Conclusions: The VF rate was very low among treatment‐experienced patients with or without an M184V/I archived mutation who switched to ABC/3TC/DTG and starting this regimen in these patients is safe and well tolerated. However, data over a longer period are needed to confirm the total absence of any impact of M184V/I on the risk of VF.

O215

Approaches towards a cure for HIV

S Fidler

Department of GUM and HIV Medicine, Imperial College and Imperial College NHS Trust, London, UK

Whilst ART has dramatically improved survival for PLWHIV, maintaining lifelong health through viral suppression requires sustainable global access to ART, lifelong daily adherence to medication, which is untenable for both the individual and implementers. An HIV cure or remission is therefore highly desirable. The accepted definition of an HIV cure is the goal of a significant period of maintained viral suppression off ART (post‐treatment viral control), maintaining zero risk of onward viral transmission as well as individual health. The key barrier to curing HIV is the persistence of virus within a pool of latently infected cells, the so‐called HIV reservoir. These cells appear to persist for the lifetime of the individual and despite years of suppressed viraemia, viral replication re‐emerges, quite rapidly on stopping ART for the vast majority of individuals. The research field of HIV cure has moved rapidly towards new innovations which are currently under trial in addition to ART to explore how to eliminate or significantly reduce the size of the measured HIV reservoir, with a view towards HIV remission. In this presentation I will explore the results of recent studies that are investigating the different approaches to HIV cure. I will present data from some of the UK studies that have recently completed and discuss the next planned studies and approaches with a discussion of what we have learnt along the way.

O216

HIV cure and cancer immunotherapy: cross‐disciplinary research at its best

S Deeks

Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA

Given the challenge of delivering complex, expensive and potentially harmful ART on a global level, there is intense interest in the development of short‐term, well‐tolerated regimens that will either fully eradicate all HIV (a “cure”) or durably prevent HIV replication in the absence of any therapy (a “remission”). Most experts agree that a remission will be easier to achieve than a complete cure. Enthusiasm for this approach is driven in part by recent advances in using novel immunotherapies to reduce and control cancer cells. Cancer and HIV persistence share a number of similarities. In each case, a rare population of cells with the capacity to cause harm becomes established in difficult‐to‐reach tissues. The local environment in cancer and perhaps HIV reshaped to prevent immune mechanisms from clearing the diseased cell. Specifically, a chronic inflammatory environment is often present, resulting in upregulation of a number of pathways which prevent effective immune responses. Therapies that target these immune pathways have either been very successful (in cancer) or now entering the clinic (in HIV disease). Recent observations in HIV‐infected adults with cancer suggest that these approaches are unlikely to cure HIV alone and might have an unacceptable safety profile. Novel approaches to enhance their efficacy and reduce risk are being developed and will be discussed.

O22 – #Adolescent Lives Matter

O221

Living with it: complications of long‐term HIV

R Ferrand

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK, and Harare, Zimbabwe

The global scale‐up of ART has dramatically increased survival of people with HIV and turned the infection from an invariably fatal disease into a chronic condition. Hence, increasing numbers of children who would previously have died in childhood are now reaching adolescence and adulthood. However, despite ART, HIV‐infected children commonly experience chronic multisystem complications that result in considerable morbidity and increased mortality risk. These include cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, neurocognitive and skin disease. These complications are likely a consequence of HIV infection itself, a sequelae of HIV‐associated infections and/or HIV treatment. As coverage of ART increases, it is increasingly apparent that ART alone is insufficient to maintain health and quality of life of children living with HIV. Research to understand the pathogenesis of these complications and to develop therapeutic strategies is needed. Looking ahead, HIV programmes will need to focus not only on delivery of ART but on management of these complications to ensure that children reaching adulthood achieve optimum health outcomes.

O222

Taking it: PrEP experiences among adolescent MSM

S Hosek

John Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, IL, USA

While oral HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has demonstrated safety and efficacy across populations, uptake and persistent use have been suboptimal among young adult MSM. Furthermore, disparities in race and health care access are emerging that may inhibit the true potential of PrEP as an HIV prevention strategy for young MSM. Prescription rates among adolescent MSM under the age of majority fall even further behind adults, due in part to ethical and regulatory interpretations of consent laws as well as limited knowledge about PrEP and subsequent discomfort of prescribers. This presentation will review the current regulatory landscape for adolescent PrEP access as well as provide data from several recent studies of PrEP knowledge, uptake, adherence and persistence among adolescent and young adult MSM.

O223

Staying with it: novel ways to increase adolescent adherence

C Foster

Imperial College NHS Trust, London, UK

Is lifelong adherence to ART, or to any medication, potentially for 80+ years, really possible? Why is adherence poorer in adolescents when compared to younger children or older adults? What is the impact of adolescent cognitive development and of mental health on adherence? Are these issues specific to adolescents living with HIV and what can we learn from other chronic diseases? With these questions in mind, how do healthcare professionals, families, peers and the wider community best support adherence for adolescents living with HIV? The existing evidence of the impact of technology, peer mentors, disclosure, education, ART simplification, economic strengthening and cash transfers will be explored, highlighting examples of best practice, yet considerable data gaps persist. The needs of the research community to move from small pilot interventions to well‐powered randomised controlled trials for adolescents struggling with adherence to ART, frequently not a favoured population for research funding, is critical.

O224

Dealing with it: mental health and stigma. Report from a study of YPLHIV in the Ukraine

M Durteste1, G Kyselyova2, A Volokha2, A Judd3, C Thorne1, R Malyuta4, V Martsynovska5,6, N Nizova6, H Bailey1, the Study of Young People Living with HIV in Ukraine

1UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, UK. 2Shupyk National Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, Kiev, Ukraine. 3MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, Institute of Clinical Trials & Methodology, University College London, London, UK. 4Perinatal Prevention of AIDS Initiative, Odessa, Ukraine. 5Institute of Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases, The Public Health Center of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, Kiev, Ukraine. 6The Public Health Center of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, Ukraine.

Background: Ukraine has the second largest European HIV epidemic. This study aimed to describe stigma, demographic and social factors and their association with anxiety among young people with perinatally‐acquired HIV (PHIV) or behaviourally‐acquired HIV (BHIV) in Kiev and Odessa.

Methods: One hundred and four young people with PHIV and 100 with BHIV aged 13 to 25 years confidentially completed a tablet‐based survey. Tools included the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (score of 8 to 10 on anxiety sub‐scale indicating mild and ≥11 indicating moderate/severe symptoms in last seven days), Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale (RSES) and HIV Stigma Scale (HSS, short version). Unadjusted Poisson regression models were fitted to explore factors associated with moderate/severe anxiety symptoms.

Results: PHIV and BHIV young people had median age 15.5 [IQR 13.9 to 17.1] years and 23.0 [21.0 to 24.3] years respectively and had registered for HIV care a median 12.3 [10.3 to 14.4] years and 0.9 [0.2 to 2.4] years previously; 97% (97/100) and 66% (65/99) respectively were on ART. Overall 30% reported mild and 13% (25/188) moderate/severe anxiety symptoms, with no difference by mode of HIV acquisition (p = 0.405) or sex (p = 0.700). Forty‐two percent (75/180) reported history of an emotional health problem for which they had not been referred/attended for care, or were unsure regarding care. Higher risk of moderate/severe anxiety symptoms was found with higher HIV‐related stigma (prevalence ratio [PR] 1.24, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.34 per HSS unit increase), lower self‐esteem (PR 0.83, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.90 per RSES point increase), less stable living situation (PR 3.13, 95% CI 1.31 to 7.47 for ≥2 vs. no home moves in last three years), CD4 ≤350 cells/mm3 (PR 2.29, 95% CI 1.06 to 4.97), having no‐one at home who knew the respondent's HIV status (PR 9.15, 95% CI 3.40 to 24.66 vs. all know) and, among BHIV, history of drug use (PR 4.64, 95% CI 1.83 to 11.85).

Conclusions: Results indicated unmet need for support. Future work is needed to explore strategies for mental health support, particularly around disclosure, self‐esteem and stigma.

O23 – Mental Health and HIV: What We All Need to Know

O23

Mental health and HIV: what we all need to know

C Orkin1, F Lampe2, C Izambert3, L Waters4

1Barts Health NHS Trust and Queen Mary University of London, London, UK; Chair, British HIV Association (BHIVA). 2Institute for Global Health, University College London, London, UK. 3AIDES, France. 4Mortimer Market Centre, University College London Hospitals, London, UK.

People living with HIV experience a higher prevalence of mental health conditions than the general population. Mental health, like HIV, attracts unacceptable levels of stigma; mental ill health negatively impacts quality of life, morbidity & mortality and adherence to medication; neuropsychiatric symptoms, including insomnia, are common and can be associated with HIV medication; medications to treat anxiety, depression and other psychiatric conditions are associated with numerous drug‐drug interactions, requiring prescribers, and patients, to understand how to manage, and mitigate, the risk of related complications. This BHIVA‐led symposium will, with BHIVA and European speakers, describe the epidemiological, stigma and drug interaction challenges related to HIV and mental health and will summarise the management of people reporting insomnia with a view to equipping the community and clinicians to improve mental health care.

O31 – HIV and Migration: a Renewed Challenge

O311

HIV and migration: a renewed challenge

J del Amo Valero

National Center for Epidemiology, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain

Migrants are heterogeneous and dynamic populations originating from a variety of countries. In Europe, migrants are exposed to multiple risk‐contexts for HIV infection, which are also related to migration drivers such as poverty and homophobia. This heterogeneity hampers the concept of “migrant” as a single category for analyses. The contribution of migrants to national epidemics varies globally but is the highest in Europe. In the European Union and Economic Area, over half of HIV reports in persons born in a different country to that of residence originate from Sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA), but HIV‐positive persons from Latin America and the Caribbean and from Western, Central and Eastern Europe account for large numbers. These different geographical origins are associated with different epidemiological characteristics, and thus require distinct interventions. The epidemiological patterns largely resemble those of the countries of origin; with a fundamentally heterosexually acquired epidemic in migrants from SSA, a very high proportion of MSM among cases from Latin America and the highest proportion of persons who inject drugs among HIV‐positive European migrants. Time trends are also different; for migrants from SSA sustained declines in new HIV reports have been observed from 2003 onwards whereas steady increases in HIV diagnoses in MSM from Latin America and the Caribbean have been reported. There is solid evidence that HIV acquisition among migrant MSM takes place largely after migration into European cities and accounts for a larger than previously thought proportion among heterosexual migrants from SSA. For most migrant groups, but particularly for undocumented migrants, difficulties to access HIV testing and health care are issues in many European countries and in some, undocumented migrants are not entitled to universal antiretroviral treatment. This talk will address how the dynamism and heterogeneity of migrant populations in Europe demands renewed answers for renewed challenges.

O32 – Coinfections: TB and Viral Hepatitis

O321

HIV‐associated tuberculosis: diagnosis, management and prevention

G Meintjes

University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa