Abstract

Background

Doxorubicin (DOX)-based chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) yields excellent disease-free survival, but poses a substantial risk of subsequent left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and heart failure, typically with delayed onset. At the cellular level, this cardiotoxicity includes deranged cardiac glucose metabolism.

Methods

By reviewing the hospital records from January 2008 through December 2016, we selected HL patients meeting the following criteria: ≥ 18 year-old; first-line DOX-containing chemotherapy; no diabetes and apparent cardiovascular disease; 18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scans before treatment (PETSTAGING), after 2 cycles (PETINTERIM) and at the end of treatment (PETEOT); at least one echocardiography ≥ 6 months after chemotherapy completion (ECHOPOST). We then evaluated the changes in LV 18FDG standardized uptake values (SUV) during the course of DOX therapy, and the relationship between LV-SUV and LV ejection fraction (LVEF), as calculated from the LV diameters in the echocardiography reports with the Teicholz formula.

Results

Forty-three patients (35 ± 13 year-old, 58% males) were included in the study, with 26 (60%) also having a baseline echocardiography available (ECHOPRE). LV-SUV gradually increased from PETSTAGING (log-transformed mean 0.20 ± 0.27) to PETINTERIM (0.27 ± 0.35) to PETEOT (0.30 ± 0.41; P for trend < 0.001). ECHOPOST was performed 22 ± 17 months after DOX chemotherapy. Mean LVEF was normal (68.8 ± 10.3%) and only three subjects (7%) faced a drop below the upper normal limit of 53%. However, when patients were categorized by median LV-SUV, LVEF at ECHOPOST resulted significantly lower in those with LV-SUV above than below the median value at both PETINTERIM (65.5 ± 11.8% vs. 71.9 ± 7.8%, P = 0.04) and PETEOT (65.6 ± 12.2% vs. 72.2 ± 7.0%, P = 0.04). This was also the case when only patients with ECHOPRE and ECHOPOST were considered (LVEF at ECHOPOST 64.7 ± 8.9% vs. 73.4 ± 7.6%, P = 0.01 and 64.6 ± 9.3% vs. 73.5 ± 7.0%, P = 0.01 for those with LV-SUV above vs. below the median at PETINTERIM and PETEOT, respectively). Furthermore, the difference between LVEF at ECHOPRE and ECHOPOST was inversely correlated with LV-SUV at PETEOT (P < 0.01, R2 = − 0.30).

Conclusions

DOX-containing chemotherapy causes an increase in cardiac 18FDG uptake, which is associated with a decline in LVEF. Future studies are warranted to understand the molecular basis and the potential clinical implications of this observation.

Keywords: Doxorubicin, Cardiotoxicity, 18FDG-PET, Left ventricular dysfunction, Heart failure

Background

Anthracyclines are the cornerstone of many life-saving treatments, and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a paradigm of a curable malignancy also by virtue of anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens, with optimal treatment providing a 10-year disease-free survival exceeding 80% [1, 2]. Unfortunately, however, anthracyclines are cardiotoxic [3].

Anthracycline cardiotoxicity may present as left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and heart failure within months or few years after exposure to high cumulative doses of drug, especially in the case of pre-existing cardiovascular disease. Nonetheless, LV dysfunction and heart failure may also develop more insidiously, several years after treatment with only moderate doses of anthracyclines [4–6]. This type of cardiotoxicity is typically observed in patients who do not have cardiovascular risk factors or disorders at the time of chemotherapy, such as first-line treated subjects with HL, for whom the incidence of anthracycline-related LV dysfunction may be as high as one in three treated patients [7].

Predicting late anthracycline cardiotoxicity is challenging. Both biomarkers and echocardiography with speckle tracking analysis or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging have been proposed to identify individuals who may require cardiac monitoring and may benefit from early cardioprotection with drugs such as beta-blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [8–11]. Yet, these tools are underused in clinical practice as they require additional exams for already overwhelmed patients, need expert personnel for appropriate interpretation of the results and, in some cases, are expensive.

Whole-body 18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) is recommended for HL staging [2, 12]. While the oncologist evaluates 18FDG uptake in the hematopoietic system, this exam may also offer unique information concerning the effects of anthracyclines on the heart. Impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism with heightened glycolytic flux is a major feature of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in experimental mouse models [13, 14]; since hexokinase, the rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, is also responsible for phosphorylation and intracellular retention of 18FDG, it is expected that myocardial uptake of this tracer increases in response to anthracycline. In fact, previous studies demonstrated a change in LV 18FDG standardized uptake value (LV-SUV) during anthracycline exposure [15] and it has been hypothesized that 18FDG-PET might detect myocardial toxicity of anthracycline very early [16]. Consistent with this literature, we recently found that 18FDG uptake increases in mice injected with the anthracycline, doxorubicin (DOX), as well as in patients receiving anthracycline-containing chemotherapy, with a direct correlation with a composite endpoint of subsequent cardiac alterations [17]. Here, we sought to expand these findings focusing on LV ejection fraction (EF), because even minor decreases in this parameter were shown to predict clinically relevant anthracycline cardiotoxicity [18].

Methods

Patient selection

This retrospective study included patients affected by HL and referred to the IRCCS San Martino Policlinic Hospital, Genova, Italy, between January 2008 and December 2016. According to the research mission of the hospital and as per approval by the local Institutional Review Board, all subjects signed an informed consent allowing the utilization of their anonymized clinical data for scientific purposes.

By reviewing the medical records, eligible patients were identified based on the following criteria (Fig. 1): age ≥ 18 years; HL receiving first-line chemotherapy with DOX as part of the ABVD or BEACOPP protocols; at least three 18FDG-PET scans available, i.e. before treatment (PETSTAGING), after 2 cycles (PETINTERIM) and at the end of treatment (PETEOT); no diabetes; no more than two major cardiovascular risk factors, no history of cardiac disease and normal ECG at baseline; and transthoracic echocardiography performed ≥ 6 months after DOX exposure (ECHOPOST). Thus, by study design all subjects underwent an echocardiogram 6 or more months after chemotherapy completion. Some patients, however, received more than one post-treatment echocardiogram: in this case, the most recent one was considered (i.e. closest to the time when the retrospective analysis was carried out). When available, data of a baseline echocardiographic evaluation (ECHOPRE) were also taken into account.

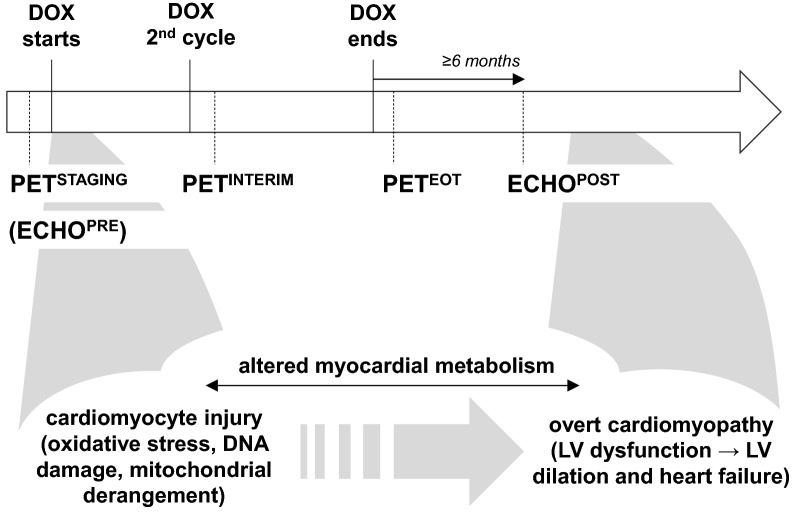

Fig. 1.

Study design and stages of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. A schematic of the timing of the 18FDG positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scans and echocardiograms taken into analysis is depicted in the upper panel, while the corresponding stages of anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity are presented in the lower part. DOX: doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy; ECHOPRE: echocardiography at baseline (available only in a subgroup of patients); ECHOPOST: echocardiography after completion of DOX chemotherapy; PETSTAGING: 18FDG-PET before treatment; PETINTERIM: 18FDG-PET after 2 cycles of doxorubicin; PETEOT: 18FDG-PET at the end of treatment; LV: left ventricular

Nuclear imaging

18FDG-PET/CT scans were performed using a 16-slice Biograph 16 PET/CT hybrid system (Siemens Medical Solutions). In accordance to standard clinical practice, each patient received an intravenous bolus of 4.8–5.2 MBq/kg 18FDG. PET/CT acquisition started after 60–75 min, during which subjects were recommended to drink water in order to increase the urinary clearance of the unbound 18FDG fraction. The body was scanned from vertex to mid-thigh in arms-up position. The emission scan lasted 120 s per bed position. PET raw data were reconstructed using ordered-subset expectation maximization (OSEM, 3 iterations; 16 subsets), and attenuation was corrected using the raw CT data. 16-detector-row helical CT was performed with non-diagnostic current and voltage settings (120 kV; 80 mA), a gantry rotation speed of 0.5 s, and a table speed of 24 mm per gantry rotation. The entire CT dataset was merged with the three-dimensional PET images using an integrated software interface (Syngo; Siemens Medical Solutions).

Volumes of interest were manually drawn on the metabolically active LV myocardium and on a 2 cm-thick section of longissimus thoracis muscle at the level of 12th vertebral body. When the LV was not clearly identifiable on PET images due to the low myocardial 18FDG uptake, hybrid PET/CT images were used to select the volume of interest. Next, the mean SUV within the LV and skeletal muscle (SM) volumes of interest were measured (LV-SUV and SM-SUV, respectively) and normalized for the circulating 18FDG concentration, as estimated by the mean SUV value in a volume of interest drawn at the level of the inferior vena cava, in order to correct for the noise signal of the blood pool. The ratio between LV-SUV and SM-SUV was then calculated. These analyses were carried out by two nuclear medicine specialists with experience in 18FDG-PET and cardiac imaging, who were blinded to other data.

Echocardiography

All patients underwent standard transthoracic echocardiography. LVEF was measured by means of the Teicholz formula by two cardiologists, different from those who selected the study cases and blinded to clinical and nuclear medicine data. Although a LVEF value was written in the echocardiography reports, this parameter was recalculated in order to have standardized and thereby comparable numbers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package of R-software (ver. 3.4). Data are given as number (percentage of total), mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). LV-SUV and SM-SUV values were normalized by logarithmical transformation. Comparisons were drawn by unpaired or paired Student’s t-test or repeated measures ANOVA, as appropriate, while the relationship between LVEF changes and LV-SUV was assessed by Pearson’s correlation test. The association between LVEF changes and LV-SUV was also examined in a linear regression model with age and DOX dose as covariates, since they can affect LV function. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Sixty-five patients were eligible during the study period, but 22 did not have ECHOPOST, leaving a sample of 43 subjects. For 26 of them (60%), ECHOPRE was available.

The baseline characteristics of the 43 patients are summarized in Table 1. Mean age was 35 ± 13 years, male gender was slightly predominant and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was low. Consistent with the fact that diabetes was a cause of exclusion from the study, mean fasting plasma glucose was normal at baseline (82 ± 9 mg/dL), and remained normal at PETINTERIM (83 ± 10 mg/dL) and PETEOT (86 ± 24 mg/dL). LVEF in the subgroup with ECHOPRE was always within the normal range.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study

| Male | 25 (58%) |

| Age (years) | 35 ± 13 |

| Age > 65 years | 0 |

| Hypertension | 0 |

| Smoke | 18 (42%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 (9%) |

| Family history of heart disease | 8 (19%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 |

| Mediastinal RT (non-cardiac field) | 6 (14%) |

| Doxorubicin dose (mg/m2) | 251 ± 57 |

| ECHOPRE | 26 (60%) |

| LVEDD (mm) | 47.2 ± 5.2 |

| LVESD (mm) | 28.2 ± 3.9 |

| LVEF (%) | 70.3 ± 7.1 |

RT: radiotherapy; ECHOPRE: baseline echocardiography; LVEDD: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVESD: left ventricular end-systolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

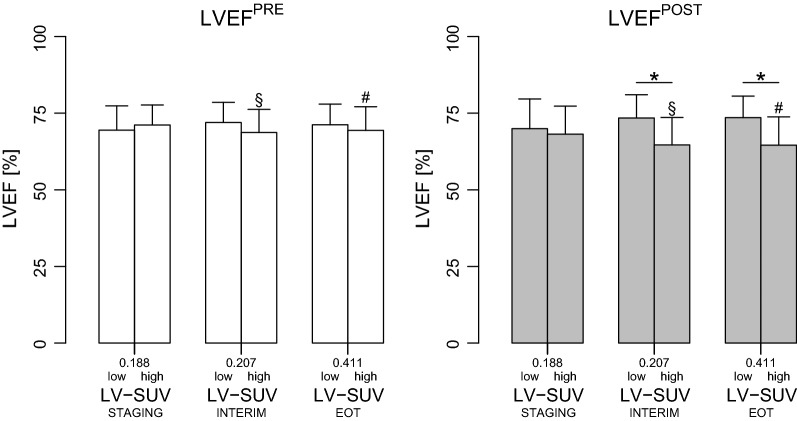

A significant progressive increase in LV-SUV was observed over DOX treatment (Fig. 2), and this trend was confirmed in the subgroup of patients with ECHOPRE (data not shown). SM-SUV also increased during chemotherapy (Fig. 2), thus no significant change occurring in the ratio between LV-SUV and SM-SUV.

Fig. 2.

18FDG uptake during doxorubicin treatment in the myocardium and in the longissimus thoracis muscle. Boxes are median and interquartile ranges of left ventricular and skeletal muscle 18FDG standardized uptake values (SUV) at the indicated 18FDG positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scans. Vertical bars indicate the highest and lowest SUV at each time point. Repeated measures ANOVA P for trend = 0.0007 and 0.02 for SUV in the heart and longissimus thoracis, respectively. STAGING: 18FDG-PET before treatment; INTERIM: 18FDG-PET after 2 cycles of doxorubicin; EOT: 18FDG-PET at the end of treatment

ECHOPOST was performed 22 ± 17 (range 6–76) months after DOX chemotherapy. LVEF dropped below the upper normal limit of 53% in 3 (7%) patients, who remained asymptomatic, and mean LVEF in ECHOPOST was normal (68.8 ± 10.3%), as was LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) (47.4 ± 5.1 mm). In the subgroup with both ECHOPRE and ECHOPOST, mean LVEF and LVEDD minimally and non-significantly changed from 69.0 ± 9.3 to 70.3 ± 7.1% (P = 0.43) and from 47.2 ± 5.2 to 46.9 ± 4.9 mm (P = 0.60), respectively.

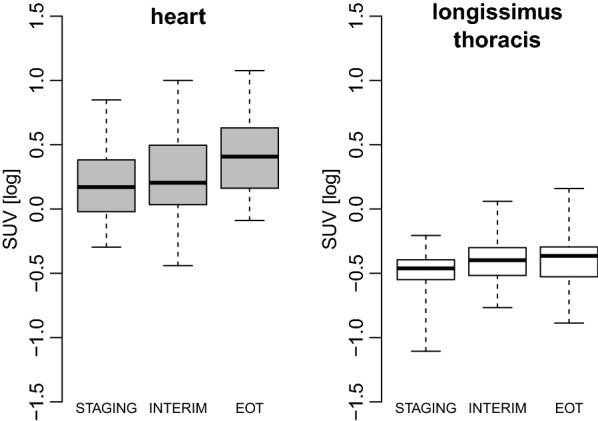

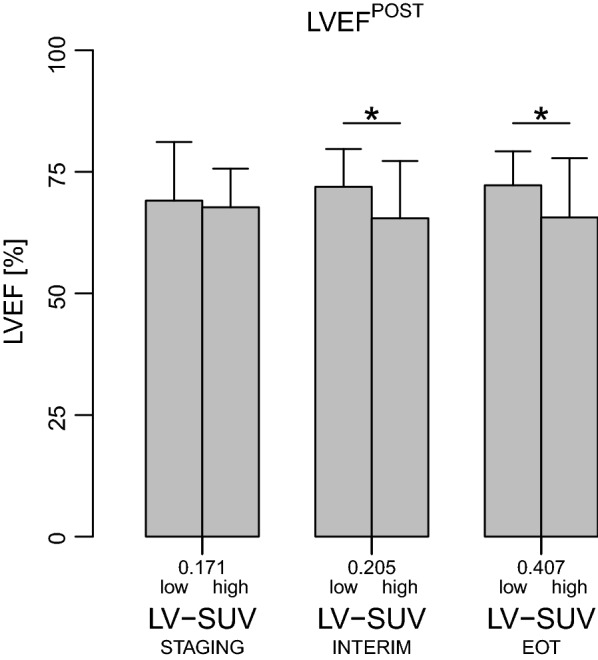

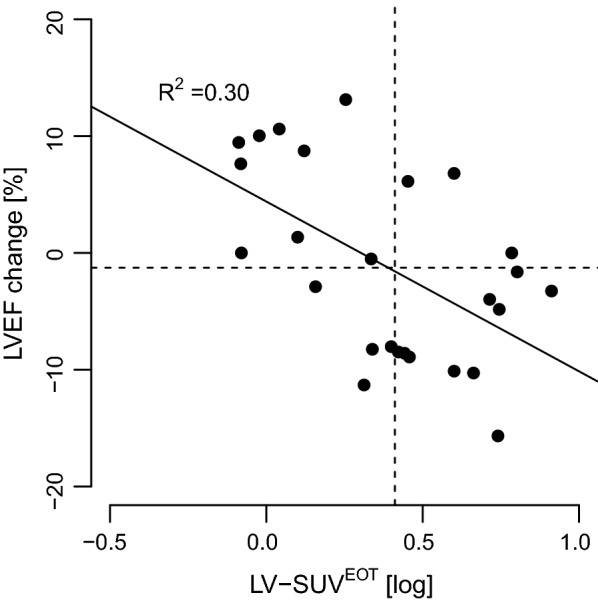

However, when patients were categorized in high and low LV-SUV by LV-SUV median value, LVEF was significantly lower in those with high vs. low LV-SUV values at both PETINTERIM and PETEOT (Fig. 3). This was also the case when only subjects with ECHOPRE and ECHOPOST were considered (Fig. 4). Interestingly, LVEF at ECHOPRE was similar among LV-SUV categories at any PET scan; consequently, LVEF as measured at ECHOPOST was significantly lower than LVEF at ECHOPRE in patients who had a high LV-SUV at either PETINTERIM or PETEOT (Fig. 4). In addition, the difference between LVEF at ECHOPRE and ECHOPOST was inversely correlated with LV-SUVEOT, the higher being LV-SUVEOT the wider the decrease in LVEF (Fig. 5). The relation between LV-SUVEOT and the magnitude of LVEF change remained significant after adjusting for age and dose of DOX (univariate analysis: β − 14.5, SE 4.6, P = 0.004; after accounting for age and DOX dose: β − 13.7, SE 4.9, P = 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Left ventricular ejection fraction according to categories of 18FDG uptake in patients with echocardiography at follow-up. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), as assessed by echocardiography performed after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy, in patients with myocardial 18FDG standardized uptake values (LV-SUV) below or above the median value (low and high, respectively) measured at each 18FDG positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scan. For each PET time point, LVEF was compared between patients with LV-SUV below vs. above the median value by unpaired t-test. * indicates P < 0.05. LV-SUVSTAGING: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET scan before treatment; LV-SUVINTERIM: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET performed after 2 cycles of doxorubicin; LV-SUVEOT: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET performed at the end of chemotherapy

Fig. 4.

Left ventricular ejection fraction according to categories of 18FDG uptake in patients with echocardiography at both baseline and follow-up. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at the baseline and follow-up echocardiography (LVEFPRE and LVEFPOST, respectively) in patients with myocardial 18FDG standardized uptake values (LV-SUV) below or above the median value (low and high, respectively) at each 18FDG positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scan. LVEF was compared between patients with LV-SUV below vs. above the median value at each PET time point by unpaired t-test and * is P < 0.05. LVEFPRE and LVEFPOST for each subgroup of patients with LV-SUV below or above the median value (e.g. LVEFPRE and LVEFPOST in subjects with high LV-SUV at EOT) were compared by paired t-test; § and # indicate P < 0.05 and < 0.01, respectively. LV-SUVSTAGING: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET scan before treatment; LV-SUVINTERIM: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET performed after 2 cycles of doxorubicin; LV-SUVEOT: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET performed at the end of chemotherapy

Fig. 5.

Relationship between left ventricular ejection fraction change and 18FDG uptake in the subsets of patients with baseline and follow-up echocardiography data available. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LV-SUVEOT: LV 18FDG standardized uptake value at positron emission tomography performed at the end of anthracycline chemotherapy

By contrast, LVEDD was not significantly different among the high and low LV-SUV categories at any PET time point (Table 2).

Table 2.

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter across categories of 18FDG uptake at each 18FDG-PET scan

| LV-SUV | LVEDD (mm) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PETSTAGING | Low | 47.3 ± 5.2 | 0.81 |

| High | 47.7 ± 5.2 | ||

| PETINTERIM | Low | 46.1 ± 4..9 | 0.11 |

| High | 48.7 ± 5.2 | ||

| PETEOT | Low | 47.7 ± 4.8 | 0.90 |

| High | 47.7 ± 5.1 |

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), as assessed by echocardiography performed after completion of anthracycline chemotherapy, in patients with myocardial 18FDG standardized uptake values (LV-SUV) below or above the median value (low and high, respectively) measured at each 18FDG positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scan

For each PET time point, LVEDD was compared between patients with LV-SUV below vs. above the median value by unpaired t-test

LV-SUVSTAGING: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET scan before treatment; LV-SUVINTERIM: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET performed after 2 cycles of doxorubicin; LV-SUVEOT: LV-SUV at the 18FDG-PET performed at the end of chemotherapy

Discussion

The present study shows that DOX-containing chemotherapy causes an increase in 18FDG uptake by the normal heart, as defined by clinical assessment, which is associated with a significant decline in LVEF several months to years after treatment completion. These results substantiate an emerging literature putting attention on the effects of anthracyclines on myocardial retention of 18FDG-PET [15–17, 19], and raise research and practical prospects.

First, our and other authors’ work prompts the question of which mechanism underlies the higher accumulation of 18FDG in the myocardium exposed to DOX as compared with control conditions. Finding the answer would imply gaining insights into the pathogenesis of DOX cardiotoxicity, which is complex and still to be fully resolved [20], and possibly laying the foundations for novel strategies to avoid or mitigate cardiac injury.

DOX and other anthracyclines acutely and invariably elicit a triad of alterations in cardiomyocytes—oxidative stress, DNA damage due to topoisomerase II poisoning and mitochondrial derangement [21]. Intriguingly, however, development of gross cardiac abnormalities is delayed, in both the animal model and, to the largest extent, patients [22, 23]. Therefore, anthracycline cardiotoxicity may be schematically divided in immediate molecular and cellular events, which occur right after drug administration, and whole-organ clinically relevant perturbations, which most often appear after a temporal gap that may last months or even years (Fig. 1). The reason for this two-stage course remains elusive, and several, likely not mutually exclusive factors, such as senescence [24] or stalled autophagy [14], have been suggested.

Abnormal energy metabolism with depressed mitochondrial oxidation and enhanced lactate-producing glycolysis characterizes both the early and the late phases of anthracycline cardiotoxicity [13, 14, 23] (Fig. 1). Within this metabolic reorganization, hexokinase displays increased activity [13, 14, 25, 26]. Since this enzyme is also thought to be responsible for the phosphorylation of 18FDG leading to intracellular tracer retention [27], it is conceivable that the augmented myocardial uptake of 18FDG following DOX chemotherapy is the consequence of heightened hexokinase activity. If so, this and other recent studies [16, 17, 19, 28] may be viewed as indirect confirmation that anthracycline-initiated impairment of energy metabolism occurs in the human heart as it does in experimental models.

There may be other explanations for cardiac 18FDG accumulation upon exposure to DOX. Intracellular mediators other than hexokinase may mediate at least part of 18FDG uptake in cardiomyocytes, as it has recently been proposed for cancer cells [29]. Furthermore, the possible contribution of an increase in the expression of transmembrane glucose (and 18FDG) transporters [30], as well as of non-cardiomyocytes, must be taken into consideration.

Regardless of how the heart becomes more avid of 18FDG after anthracycline chemotherapy, this phenomenon might be exploited for cardiotoxicity surveillance.

Nowadays, LVEF monitoring by repeated echocardiography is the standard of care to detect anthracycline cardiotoxicity, but it captures only the late steps of anthracycline-elicited cardiomyopathy, when global LV systolic dysfunction develops. The ideal marker should allow the recognition of anthracycline damage much earlier, when cardiac homeostasis is profoundly disrupted but the whole heart appears normal. Both troponin, a biomarker of cardiomyocyte injury [31], and echocardiography with LV global longitudinal strain analysis, which identifies an impairment in myocardial deformation that occurs when LVEF is still preserved, have been proposed for the scope [8, 9, 11]. Nevertheless, implementation of these screening approaches in clinical practice is difficult, one main reason being that they represent further procedures added to the already high number of diagnostic tests the oncological patient undergoes, with not negligible personal and health care costs.

By contrast, 18FDG-PET offers the unique advantage that it is routinely performed for HL [1, 2, 32] and does not require additional radiation or exam prolongation. In our cohort, higher myocardial 18FDG uptake was associated with a small but significant drop of LVEF values to the very low part of the range of normality, suggesting that systematic analysis of radiotracer retention by the heart during 18FDG-PET done for oncological purposes may be another way to detect anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Additional work is needed to confirm this opportunistic use of 18FDG-PET and whether cardiac 18FDG accumulation may anticipate LVEF decline, since we did not evaluate echocardiograms performed at the same time of PET scans. Similarly, it has to be investigated whether and how 18FDG-PET can be integrated with other imaging techniques and/or circulating biomarkers.

Only a few of our patients had LVEF below the upper normal limit and there were no cases of heart failure at follow-up. Nonetheless, the study population was made of young individuals with low cardiovascular risk, for whom minor decreases in LVEF are not expected and must be deemed biologically relevant, even though clinically silent. This is even more so considering that such patients are generally believed not to be prone to cardiovascular events and therefore are not monitored in this regard. Moreover, it was shown that subjects treated with anthracyclines who initially face a small reduction in LVEF are at greatest risk of developing heart failure over time [18].

There are some limitations of this work to be acknowledged. Because of the retrospective design, LVEF was calculated from reported LV diameters. However, in the presence of normal LV size and regional kinesis like for the cases we reviewed, the Teicholz formula is reliable to estimate LVEF [7]. Second, the 18FDG-PET scans we analyzed were obtained without any dietary preparation of the patients, as it is routinely done in oncological practice. Even though we corrected for SM activity, it cannot be excluded that at least part of the variations in myocardial tracer uptake were due to different dietary regimens followed by the studied subjects. Prospective investigations are needed to overcome this shortcoming, by including a high-fat low-carbohydrate diet or pharmacological preparation to minimize diet-dependent LV-SUV variability. Finally, the method used to evaluate myocardial metabolism in non-dedicated 18FDG-PET is not yet standardized and the LV-SUV thresholds according to which patients were categorized were arbitrary. Future studies should define the optimal technical aspects and reduce inter-reader and inter-scanner variability [33].

Conclusions

We propose 18FDG-PET as a tool to better characterize and monitor anthracycline toxicity on the human heart, with potential clinical implications. Further research is warranted to support this claim and expand the evidence from low-risk subjects like the ones we studied to a population that ultimately develop heart failure. From the basic science standpoint, our results reiterate the emphasis on the metabolic aspects of anthracycline cardiotoxicity.

Authors’ contributions

MS, EA, SC, SM, MM and AGC reviewed the medical records, selected the eligible patients and created the study dataset. MB and CM analyzed the 18FDG-PET data. GG and MB analyzed the echocardiography data. MS, GS, CB, PA and PS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients admitted to the hospital where the study was carried out sign a written informed consent for use of their data for research purposes, as approved by the institutional Ethics Committee.

Funding

This study was funded by the program “Ricerca Corrente,” line “Guest-Cancer Interactions,” by Compagnia di San Paolo (Project ID Prot.: 2015.AAI4110.U4917).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- HL

Hodgkin lymphoma

- LV

left ventricle

- 18FDG

18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose

- PET

positron emission tomography

- LV-SUV

left ventricular standardized uptake value

- DOX

doxorubicin

- PETSTAGING

PET before treatment

- PETINTERIM

PET after 2 cycles

- PETEOT

PET at the end of treatment

- ECHOPRE

baseline echocardiography

- ECHOPOST

follow-up echocardiography

- LVEF

ejection fraction

- LVEDD

LV end-diastolic diameter

- CT

computed tomography

- SM

skeletal muscle

Contributor Information

Matteo Sarocchi, Email: matteosarocchi@gmail.com.

Matteo Bauckneht, Email: matteo.bauckneht@gmail.com.

Eleonora Arboscello, Email: eleonora.arboscello@alice.it, Email: eleonora.arboscello@hsanmartino.it.

Selene Capitanio, Email: selene.capitanio@hsanmartino.it.

Cecilia Marini, Email: cecilia.marini@unige.it.

Silvia Morbelli, Email: silvia.morbelli@unige.it.

Maurizio Miglino, Email: ematlab@unige.it.

Angela Giovanna Congiu, Email: angelagiovanna.congiu@hsanmartino.it.

Giorgio Ghigliotti, Email: gghiglio@unige.it.

Manrico Balbi, Email: Manrico.Balbi@unige.it.

Claudio Brunelli, Email: bc@unige.it.

Gianmario Sambuceti, Email: Gianmario.Sambuceti@unige.it.

Pietro Ameri, Phone: +390103538928, Email: pietroameri@unige.it.

Paolo Spallarossa, Email: paolo.spallarossa@unige.it.

References

- 1.Ansell SM. Hodgkin lymphoma: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(7):771–779. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrington SF, Kirkwood AA, Franceschetto A, et al. PET-CT for staging and early response: results from the response-adapted therapy in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma study. Blood. 2016;127(12):1531–1538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-679407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith LA, Cornelius VR, Plummer CJ, et al. Cardiotoxicity of anthracycline agents for the treatment of cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Yeo F, et al. Cumulative burden of cardiovascular morbidity in paediatric, adolescent, and young adult survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nimwegen FA, Schaapveld M, Janus CPM, et al. Cardiovascular disease after Hodgkin lymphoma treatment: 40-year disease risk. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):1007–1017. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aleman BMP, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Klokman WJ, van’t Veer MB, Bartelink H, van Leeuwen FE. Long-term cause-specific mortality of patients treated for Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(18):3431–3439. doi: 10.1200/jco.2003.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hequet O, Le QH, Moullet I, et al. Subclinical late cardiomyopathy after doxorubicin therapy for lymphoma in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1864–1871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(36):2768–2801. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curigliano G, Cardinale D, Suter T, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity induced by chemotherapy, targeted agents and radiotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 7):155–166. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spallarossa P, Maurea N, Cadeddu C, et al. A recommended practical approach to the management of anthracycline-based chemotherapy cardiotoxicity: an opinion paper of the working group on drug cardiotoxicity and cardioprotection, Italian Society of Cardiology. J Cardiovasc Med Hagerstown Md. 2016;17(Suppl 1):S84–S92. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, et al. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(9):911–939. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the international conference on malignant lymphomas imaging working group. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3048–3058. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.53.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1639–1642. doi: 10.1038/nm.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Sala V, De Santis MC, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma inhibition protects from anthracycline cardiotoxicity and reduces tumor growth. Circulation. 2018 doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.117.030352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borde C, Kand P, Basu S. Enhanced myocardial fluorodeoxyglucose uptake following adriamycin-based therapy: evidence of early chemotherapeutic cardiotoxicity? World J Radiol. 2012;4(5):220–223. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i5.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorla AKR, Sood A, Prakash G, Parmar M, Mittal BR. Substantial increase in myocardial FDG uptake on interim PET/CT may be an early sign of adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41(6):462. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauckneht M, Ferrarazzo G, De Fiz F, et al. Doxorubicin effect on myocardial metabolism as a pre-requisite for subsequent development of cardiac toxicity: a translational 18F-FDG PET/CT observation. J Nucl Med. 2017 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.191122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mousavi N, Tan TC, Ali M, Halpern EF, Wang L, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular size and function as predictors of symptomatic heart failure in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50–59% treated with anthracyclines. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Park KS, Jeong G-C, et al. Routine oncologic FDG PET/CT may be useful for evaluation of cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(supplement 1):1549. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groarke JD, Nohria A. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: a new paradigm for an old classic. Circulation. 2015;131(22):1946–1949. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercurio V, Pirozzi F, Lazzarini E, et al. Models of heart failure based on the cardiotoxicity of anticancer drugs. J Card Fail. 2016;22(6):449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyu YL, Kerrigan JE, Lin C-P, et al. Topoisomerase II mediated DNA double-strand breaks: implications in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and prevention by dexrazoxane. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8839–8846. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varricchi G, Ameri P, Cadeddu C, et al. Antineoplastic drug-induced cardiotoxicity: a redox perspective. Front Physiol. 2018;9:167. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spallarossa P, Altieri P, Aloi C, et al. Doxorubicin induces senescence or apoptosis in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes by regulating the expression levels of the telomere binding factors 1 and 2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(6):H2169–H2181. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00068.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carvalho RA, Sousa RPB, Cadete VJJ, et al. Metabolic remodeling associated with subchronic doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Toxicology. 2010;270(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berthiaume JM, Wallace KB. Persistent alterations to the gene expression profile of the heart subsequent to chronic doxorubicin treatment. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2007;7(3):178–191. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-0026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, et al. The [14c]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat1. J Neurochem. 1977;28(5):897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauckneht M, Morbelli S, Fiz F, et al. A score-based approach to 18F-FDG PET images as a tool to describe metabolic predictors of myocardial doxorubicin susceptibility. Diagnostics. 2017;7(4):57. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics7040057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marini C, Ravera S, Buschiazzo A, et al. Discovery of a novel glucose metabolism in cancer: the role of endoplasmic reticulum beyond glycolysis and pentose phosphate shunt. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):25092. doi: 10.1038/srep25092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hrelia S, Fiorentini D, Maraldi T, et al. Doxorubicin induces early lipid peroxidation associated with changes in glucose transport in cultured cardiomyocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Biomembr. 2002;1567:150–156. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00612-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Lamantia G, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–3067. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keyes JW. SUV: standard uptake or silly useless value? J Nucl Med. 1995;36(10):1836–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.