Abstract

Nigeria, in its quest to strengthen its primary healthcare system, is faced with a number of challenges including a shortage of clinicians and skills. Methods are being sought to better equip primary healthcare clinicians for the clinical demands that they face. Using a mentorship model between developers in South Africa and Nigerian clinicians, the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) for adult patients, a health systems strengthening programme, has been localised and piloted in 51 primary healthcare facilities in three Nigerian states. Lessons learnt from this experience include the value of this remote model of localisation for rapid localisation, the importance of early, continuous stakeholder engagement, the need expressed by Nigeria’s primary healthcare clinicians for clinical guidance that is user friendly and up-to-date, a preference for the tablet version of the PACK Adult guide over hard copies and the added value of WhatsApp groups to complement the programme of face-to-face continuous learning. Introduction of the PACK programme in Nigeria prompted uptake of evidence-informed recommendations within primary healthcare services.

Keywords: health policy, health systems, public health, treatment

Summary box.

Nigeria’s National Health Policy aims to strengthen primary healthcare but is faced with a number of constraints including a shortage of staff and clinical skills. Methods are being sought to better equip primary healthcare clinicians for the clinical demands they face.

The global version of the Practical Approach to Care Kit for adult patients (PACK Adult) guide and training materials were localised for use in Nigeria and piloted over a period of 18 months using a mentorship model involving frequent electronic communication between developers in South Africa and Nigeria.

A critical success factor in this project was extensive continuous engagement between a respected local partner with a long track record of improving health systems in Nigeria and key local stakeholders.

An evaluation conducted after initial training and implementation of the PACK Nigeria Adult programme confirmed a strongly favourable response from clinicians and policy makers and high usage of the guide during consultations.

Availability of medicines, equipment and tests was facilitated through the introduction of a fully localised, standardised guide promoting uniform clinical practices.

Introduction

In Nigeria, with a population of over 193 million,1 improving coverage and quality of healthcare is a major undertaking (table 1). The National Health Policy for reforming healthcare delivery in Nigeria aims to strengthen primary healthcare (PHC), in order ‘to deliver effective, efficient, equitable, accessible, affordable, acceptable and comprehensive health care services to all Nigerians’.2 3

Table 1.

Country profile of Nigeria

| Life expectancy at birth (2016) | 55.7 (women); 54.7 (men) |

| Under-five mortality rate per 1000 live births (2016) | 104.3 (77.4–139.5) |

| Maternal mortality ratio per 100 000 live births (2015) | 814 (596–1180] |

| Density of physicians per 1000 population (2009) | 0.376 |

| Density of nurses and midwives per 1000 population (2008) | 1.489 |

| Total expenditure on health as percentage of gross domestic product (2014) | 3.7 |

| General government expenditure on health as percentage of total government expenditure (2014) | 8.2 |

| Private expenditure on health as percentage of total expenditure on health (2014) | 74.9 |

| Poverty head count ratio at $1.25 a day (PPP) (% of population) (2011) | 54.4 |

Source: Global Health Observatory August 2018 (http://apps.who.int/gho/node.cco).

PPP, adjusted for purchasing power parity

Among significant challenges is a shortage of clinicians and a low level of skills among those working in PHC facilities.4 The combined ratio of doctors, nurses and midwives to the population in Nigeria in 2012 was 0.336 per 1000 population,5 lower than the suggested 2.28 per 1000 required to achieve even modest coverage for essential health interventions.6 The skills of clinicians working in 1242 randomly sampled health facilities in six states, Anambra, Bauchi, Cross River, Ekiti, Kebbi and Niger, were assessed in a World Bank survey conducted in 2013. The assessment involved medical vignettes; seven clinical cases that constituted the highest burden in children and adults and most commonly presented at health facilities. Only 37% of the PHC workers were able to correctly diagnose all seven cases and only 17% recommended the correct treatment.7

In 2014, a task-shifting policy8 was developed that promotes redistribution of tasks between the different categories of PHC clinician: doctors, nurses, midwives, community health officers (CHOs), community health extension workers (CHEWs) and junior community health extension workers (JCHEWs). Although this policy has achieved some successes, for example, improvement of access to long-acting reversible contraception,9 improved knowledge on the management of stroke10 and access to mental health services11 in some regions of the country, there is little evidence of a general improvement in the delivery of comprehensive PHC.

In order to address this skills deficit, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) proposed to introduce the Practical Approach to Care Kit or PACK programme. The PACK programme is a health systems intervention that supports streamlined delivery of primary care by frontline clinicians in low-resource settings. It has four components: a clinical guide for point of care use, an in-service training strategy, a health systems strengthening component and monitoring and evaluation. The programme was developed by the Knowledge Translation Unit in Cape Town, South Africa, through a process of formative research spanning 18 years, and has been scaled up in primary care facilities throughout South Africa by the National Department of Health. The PACK guide is evidence-aligned, updated annually and focuses on poorly resourced health systems. A global version of the PACK Adult guide has been developed12 13 and has also been successfully localised for and implemented in other low-middle income countries.14 15 The process of localisation involves more than adaptation, as it may involve creation of new context-specific content to accommodate the disease profile, national treatment policies and guidelines, essential drug lists and staff composition of the host country. Pragmatic clinical trials and qualitative research studies have confirmed the positive impact of introducing PACK programme on quality of adult PHC and staff satisfaction.13 16–18 The logic model for PACK is that providing clear actionable point of care clinical guidance to the whole clinical team, that is, all cadres of clinician, accompanied by a customised continuous programme of case-based on-site in-service training19 and supportive supervision, improves clinical competence, encourages teamwork and task-sharing and effects health system change through prompting standardisation of care, including the supply of essential equipment, medicines and tests, and pathways for referral.

The initiative to pilot PACK in Nigeria was sponsored by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), and three states in Nigeria, Adamawa, Nasarawa and Ondo, supported by Oxford Policy Management and implemented by Health Resources International West Africa (HRIWA) in partnership with the Knowledge Translation Unit of the University of Cape Town Lung Institute (KTU) and BMJ and carried out within the framework of the World Bank-assisted performance-based financing initiative. This paper describes the localisation of the PACK programme for Nigeria by HRIWA with mentorship from the KTU, its pilot implementation in three states and lessons learnt from this experience.

Localising the PACK global programme to become Practical Approach to Care Kit Nigeria

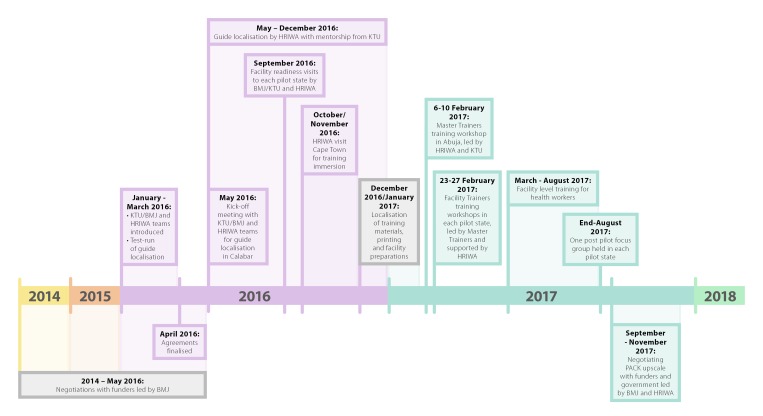

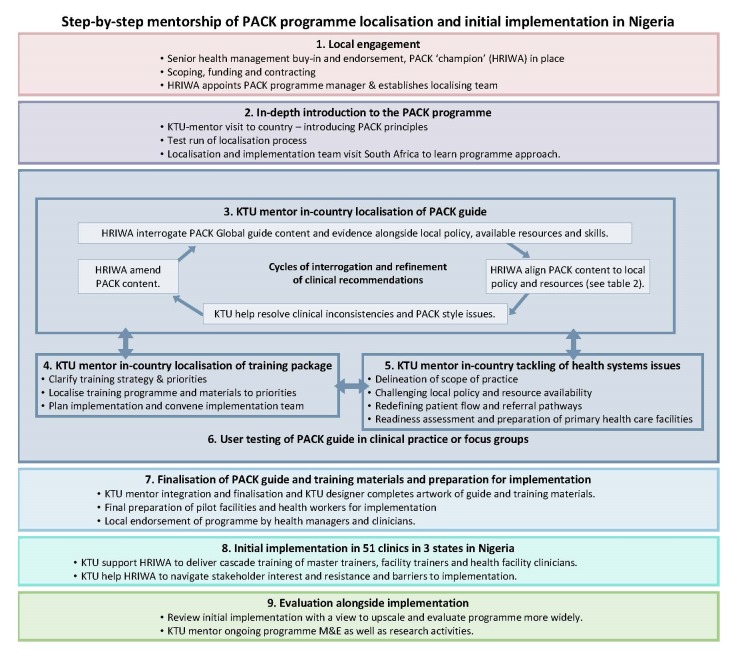

The PACK Nigeria programme was developed and piloted over 18 months (figure 1), using the localisation mentorship methodology described by Cornick and colleagues in this collection (figure 2).20

Figure 1.

Timeline of localisation and pilot implementation of PACK Nigeria Adult in three Nigerian states. BMJ, British Medical Journal; HRIWA, Health Resources International West Africa; KTU, Knowledge Translation Unit of the University of Cape Town Lung Institute; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit.

Figure 2.

Step-by-step mentorship of PACK programme localisation and initial implementation in Nigeria. HRIWA, Health Resources International West Africa; KTU, Knowledge Translation Unit of the University of Cape Town Lung Institute; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit.

Local engagement

From the outset, HRIWA, BMJ and KTU worked to secure approval and support for the PACK programme in Nigeria from the Federal Ministry of Health, NPHCDA and equivalents in each state in which PACK might be implemented and clinician regulatory bodies. High-level meetings were held with the Minister of Health and the heads of agencies and regulatory bodies and with educational institutions. The support of these stakeholders was essential for this programme to be sustainable.

Introduction to the Practical Approach to Care Kit programme

The introduction of the HRIWA to PACK involved three activities. First, two members of the PACK team conducted a 3-day introductory workshop for the 11-member HRIWA team in Calabar, Cross River state in Nigeria between the 16 and 18th May 2016 (figure 1). The HRIWA team was led by a family physician and comprised a project manager, three medical officers with local PHC experience and two community health practitioners.

Next, the teams took part in a practice ‘dry run’ of the localisation process. Communication between the KTU content mentors and HRIWA team was conducted via an online project management tool, Trello, regular emails and weekly teleconferences between Cape Town, Calabar and London. The ‘Fever’ page from the generic PACK Adult Global guide was chosen and developed for conditions in Nigeria through an iterative process of communication.

Finally, three HRIWA team members visited Cape Town, South Africa, between 12 and 19 November 2016 (figure 1) for an immersion course on the PACK training approach to take part in PACK training sessions in progress in the Western Cape and begin to plan for localisation of the training programme for Nigeria.

Localisation of the Practical Approach to Care Kit guide

Prompted by the need to complete the project within a funding window the guide was localised in 6 months, a process that in other countries had taken more than a year. This was facilitated by the readiness of the HRIWA team in Calabar to proceed and their organisation of developers into three teams working in parallel on different sections of the guide.

The 2016 edition of the PACK Adult Global guide in template form was localised section by section. The HRIWA team reviewed each page and the associated evidence database, developed and provided by the KTU, and then consulted Nigerian national guidelines and policies (listed in table 2), and also considered local disease prevalence and feasibility of management steps within the Nigerian health system. Based on these considerations, they developed recommendations and management algorithms. Clinical workshops were convened when specialist input was required. Health managers from Adamawa and Ondo states visited the HRIWA team and provided valuable input around systems issues like clinician scope of practice and availability of equipment, tests and medicines. The KTU content mentor reviewed each localised page for adherence to the PACK style and coherence with recommendations on other pages, providing more in-depth mentorship around the development of algorithms, based on KTU’s prior experiences with localisation.

Table 2.

List of Nigerian guidelines consulted

| Title | Date of publication |

| Client Tracking. Standard Operating Procedure HIV/AIDS | 2010 |

| Curriculum For Certificate in Community Health | 2006 |

| Curriculum For Diploma in Community Health | 2006 |

| Curriculum For Higher Diploma in Community Health | 2006 |

| Federal Republic of Nigeria Essential Medicines List | 2010 |

| Federal Republic of Nigeria Standard Treatment Guidelines | 2008 |

| Minimum Standards For Primary Health Care in Nigeria | 2012 |

| National Guidelines For HIV and AIDS Treatment and Care in Adolescents and Adults | 2010 |

| National Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Buruli Ulcer Management and Control Guidelines | 2015 |

| Standard Operating Procedure for the Provision of Antiretroviral Treatment in Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/AIDS Services (SIDHAS) supported sites | 2010 |

| Standing Orders For Community Health Officers and Community Health Extension Workers | 2015 |

| Standing Orders For Junior Community Health Extension Workers | 2015 |

| Task-shifting and Task-sharing Policy for Essential Health Care Services in Nigeria | 2014 |

At the time of localisation, only the 2008 Nigerian National Standard Treatment Guideline and 2010 National Essential Medicines list were available, as the 2016 editions of each were in preparation. The NPHCDA permitted access to the 2015 Standing Orders for JCHEWS and CHO/CHEWS before they were released for general use, which ensured that the PACK Nigeria guide was aligned with these. As Standing Orders for JCHEWs, CHEWs and CHOs were, to some extent, based on local expert opinion and not recent advances in evidence synthesis,21 22 the Community Health Practitioners Registration Board agreed that, where PACK Global and Standing Orders differed, recommendations could be aligned with the PACK Global guide. This decision had an impact on several recommendations, for example, antibiotic prophylaxis for premature rupture of membranes in the pregnant woman.

The PACK Nigeria guide had to be suitable for use by all cadres of clinicians. Although separate Standing Orders are published for each cadre currently, at times they failed to provide sufficient clarity on the limits of roles and responsibilities. Initially, the NPHCDA proposed that a separate version of PACK should be produced for each cadre but agreed to a single document for all cadres when HRIWA demonstrated the value of a common ‘hymn sheet’. They referred to the ‘dry run’ for the management of fever which, on a single page, was aligned with local policy and common causes of fever but integrated management by all six cadres with the role of each delineated using the standard PACK system of colour-coding medications and interpretation of tests. This exercise was key to obtaining acceptance for a single PACK Nigeria guide for all clinicians and also prompted a review of some Standing Orders recommendations and task-shifting policy documents.8 The latter necessitated extensive discussion with regulatory authorities for clarification and changes in scope of practice of some cadres of clinicians. For example, JCHEWs had previously been prohibited from administrating life-saving epinephrine for the management of life-threatening anaphylaxis. This was changed, and all clinician cadres are now authorised to administer epinephrine for this indication. However, JCHEWs are still barred from administering intravenous medications.

Localisation of the training materials

PACK Global training materials and educational tools (largely case scenario based) were also localised to be consistent with the PACK Nigeria Adult guide. The training curriculum for the pilot implementation was agreed, based on priority diseases and needs expressed by the clinicians in the pilot states.

User testing of Practical Approach to Care Kit Nigeria guide in clinical practice

End-user testing in the pilot states was conducted by HRIWA before the completion of the guide to ensure appropriateness of prescriber levels, availability of medications and investigations and feasibility of referral pathways. Forty-five clinicians selected across the pilot states were trained to use the draft PACK Nigeria Adult Guide and supplied with copies of several pages of the guide. They provided feedback on a self-administered questionnaire. Some clinicians were concerned that using a guide during consultations might be seen by patients as an obstacle to communication. However, they appreciated the clear display of clinician scope of practice and how the guide helped them identify life-threatening illness needing urgent attention. Feedback also highlighted the need to cover the care of young children (which PACK Adult does not address) and pregnant women (which it does). It identified inconsistencies in availability of recommended medications and equipment, especially in rural areas. This was communicated to state PHC development agencies and incorporated in a PACK facility readiness checklist to ensure adequate stocks of necessary medications, test kits and equipment.

Preparation for implementation

While PACK Nigeria was in development, the Adamawa State PHC development agency was working with the International Committee of the Red Cross to introduce a digital version of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness, and in Ondo, clinicians were using tablets to view training videos. Both federal and state level stakeholders expressed strong interest in a digital version of the PACK Nigeria guide. Since the KTU23 and others24 have reported improved user experience and better adherence to protocols when a digital guide was used, a digital version of the PACK Nigeria Adult guide (e-PACK) was prepared as a .pdf document by the KTU design team and downloaded onto tablet devices by BMJ and HRIWA in preparation for pilot testing in clinics.

Initial implementation

The training programme in Nigeria followed the PACK educational outreach strategy19 that aimed to familiarise clinicians with the features and use of the guide as well as profile local clinical priorities, along with the conditions assessed in the World Bank survey7 representing deficiencies in care. The PACK educational outreach strategy employs a cascade approach that enables rapid scale-up across multiple clinicians and facilities. National Lead Trainers, trained by KTU in Cape Town, train state-level master trainers, who in turn train facility trainers who deliver to facility staff. The latter occurs in 2 weekly, short, on-site and in-service training sessions that are orientated towards promoting continuous learning and a team approach, thereby alternating learning with practice.

Four master trainers from each pilot state were trained by HRIWA’s National Lead Trainers, supported by KTU training mentor in a 4-day workshop in Abuja, Federal Capital City. Chief executives and managers from partner organisations from each pilot state, NPHCDA and regulatory boards participated on the final day of training to familiarise themselves with the programme and show their support. Master trainers, supported by HRIWA National Lead Trainers, then trained 52 facility trainers from the three states during 4-day workshops in each state capital. Key stakeholders from local government and professional associations attended the last day of each workshop. Thereafter, facility trainers, supported by master trainers and HRIWA National Lead Trainers began eight fortnightly training sessions in 51 pilot facilities. During the pilot period, the HRIWA National Lead Trainers also conducted three supervisory visits to the pilot states.

Monitoring and evaluation

Limited monitoring and evaluation was undertaken with master and facility trainers, supported and mentored by the HRIWA National Lead Trainers. Methods used to assess the operational performance and impact of the PACK Nigeria pilot programme were training attendance registers, training feedback forms, pretraining and post-training testing and focus group discussions.

By the end of the pilot, 354 clinicians had been trained to use the PACK Nigeria guide: 161 CHEWs, 90 JCHEWs, 56 nurses, 22 CHOs, 19 midwives and 6 medical officers. Overall, 90% of clinicians trained completed all eight sessions, in which 83% in Adamawa, where some civil conflict limited training. The first training session included non-clinical staff in the facility so that the whole team became aware of the intervention even though only the clinicians were assessed. The results of these assessments are presented in box 1.

Box 1. Results of pretraining and post-training assessments and user experience of clinicians in the pilot evaluation of PACK Nigeria Adult and results of focus groups comparing paper and electronic tablet versions of the guide.

Pretraining and post-training assessment of clinical knowledge and skills:

Before the first and after the last training sessions, a self-administered paper-based questionnaire of multiple-choice questions assessing clinical decision making was completed by trainees. Two hundred and fifty-three (71%) clinicians completed both pretest and post-test. The pretraining test scores were generally low, averaging 24.6% (3.7/15) across all states. After training, the average score increased to 46% (a point score of 6.9 out of a maximum score of 15), a substantial improvement of 86%.

Assessment of user experience:

Two hundred and sixty-five clinicians completed a questionnaire on their experience of using the guide and of the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) programme: 73% reported using the PACK guide with almost every patient, 92% reported finding the guide easy to use, 95% reported that the guide was useful in their daily work, 94% agreed that it had improved their ability to make diagnoses and 95% agreed that PACK had improved their ability to manage patients. Sixty-three per cent of respondents felt that using PACK reduced the amount of time spent with the patient and 95% that PACK had increased their confidence in their day-to-day work. Almost all trainees reported that by following the PACK guide they had a clear understanding of their prescribing authority (95%) and when and to whom or what level of care to refer patients.

Focus group discussions at the end of the pilot period:

Master trainers in each state, assisted by Health Resources International West Africa (HRIWA), moderated focus group discussions with six to nine clinicians who had used both the paper and e-versions of the PACK Nigeria Adult guide. The group considered the impact, strengths and weaknesses of the PACK programme and provided views on the comparison of the paper and digital version of the guide. A thematic analysis of the discussions found that they felt the PACK guide contained the standard of care required of them, clearly defined their scope of practice and provided a uniform standard for diagnosing and treating patients, supporting them to deliver effective primary healthcare to their patients. Users in Adamawa and Ondo States reported that the guide had resulted in more appropriate requests for investigations and identified a reduction in prescriptions and polypharmacy, effects that may have significant resource implications for the health system. All three states indicated a clear preference for e-PACK over the hard copy largely because of ease of use and acceptability to patients. Although e-PACK offered navigational ease over the hard copy version, it did not easily enable users to return to their previous page. Battery life was also insufficient for a full shift, complicated by unreliable power supply in some facilities.

In summary, pretraining scores were low in all states but increased substantially after training. User experience was generally strongly positive in terms of ease of use, usefulness during consultations, improved ability to diagnose and manage patients and when to refer, increased confidence as clinicians and appreciation of their scope of practice. A high proportion of the clinicians reported using the guide in most consultations. The focus groups confirmed similar experiences and views and a clear preference for the e-PACK version. Some participants reported that use of PACK reduced polypharmacy prescribing and reduced the number of investigations ordered per patient.

Midway through the pilot, 43 tablets with e-PACK were introduced in 20 facilities across the three states. This was delayed to ensure that initial PACK training focused on the content rather than the format of the guide and allowed time to identify suitable facilities to test the tablet format. Clinicians were encouraged to use the tablet during all consultations.

A critical element that sustains the PACK programme is the provision of ongoing supportive supervision to PACK trainers and clinicians. In Nigeria, some of this support was delivered via social media, an approach that has been successful elsewhere.25 Four WhatsApp groups were created: three for the state-level facility trainer groups and one for the master trainers. Over 6 months, 2236 messages were shared, providing support for facilities and trainers, scheduling administrative meetings, announcements, supervisory messages, feedback on guide use and sharing stories of successful patient care using PACK Nigeria. Quarterly action plans, records of training and photographs and videos of training sessions were also shared.

Challenges and limitations of the Practical Approach to Care Kitk Nigeria Adult Project

As expected during the development and introduction of a complex health system intervention, several challenges and limitations were encountered:

Clinicians and health administrators at state level and the NPHCDA expressed strongly the need to broaden the scope of the PACK Nigeria guide to include children, as children constitute the majority of patients seeking care at PHC facilities.

Despite recent attempts to strengthen health services and ensure that facilities intended for the PACK pilot were prepared, essential equipment, tests and medicines were still not complete in some facilities. Implementing PACK assisted managers by surfacing specific gaps that required attention.

Owing to limitations of budget and time, a more complete and technically robust evaluation of the programme could not be conducted. Important potentially useful information on changes in practice and prescribing patterns and other process measures could not be evaluated.

Lessons learnt

Use existing networks to ensure early and continuous stakeholder engagement

The widespread, federal and state-level, intersectoral (health system and health education system) and regulatory engagement from the start along with end-user engagement during localisation was an important contributor to the enthusiastic uptake of PACK in Nigeria. Stakeholder engagement also occurred at ground level with clinicians and managers in clinics at various stages of programme development and in the preparation for and during pilot implementation of the guide. These stakeholder engagements enabled early access to 2015 Standing Orders for JCHEWs and CHO/CHEWs, integration of the clinical practice of all six cadres of PHC clinicians into one single PACK guide and facilitated speedy resolutions where recommendations differed between PACK Global and Standing Orders. These engagements were facilitated by the HRIWA team’s network, credentials and collaborative approach and by a leader with significant professional standing as a former commissioner for health with a track record of strengthening Nigerian health services at both state and federal levels.

A remote mentorship model of localisation can achieve quality and timeous completion of the Practical Approach to Care Kit guide

Remote mentorship first developed in the localisation of PACK Adult in Brazil15 was refined during the PACK Nigeria localisation and resulted in more rapid completion of the guide. Contact between the teams facilitated by the overall KTU/BMJ managers of the project took place several times per week. Localisation was also streamlined as a result of a high rate of adoption of PACK Global Adult recommendations, partly attributable to the fact that several local guidelines and policies were outdated and required revision and that their development had previously relied largely on expert opinion rather than rigorous evidence synthesis.

Primary healthcare clinicians prefer a digital version of the Practical Approach to Care Kit guide

Most clinicians preferred e-PACK to the paper version although some technical challenges in rural facilities need to be addressed, such as battery life.

Use WhatsApp to support Practical Approach to Care Kit Nigeria cascade training

Use of WhatsApp to establish group discussions about clinical practice and use of the PACK guide proved a valuable means of supporting trainees and facility trainers and encouraging their continued use of the guide.

Next steps

Plans for scale up, expansion of content and integration into training curricula

Before the results of the small evaluation were known, managers from all three pilot states expressed their intention to scale up PACK to all their PHC facilities, and the NPHCDA indicated that it would like to introduce the PACK Nigeria programme nationally, starting with the remaining new Nigerian State Health Investment Project (NSHIP) states in the North East zone. PACK Nigeria will be included in the pilot of the Federal Ministry of Health Basic Health Care Provision Fund of the National Health Act 2014 in three more states and will see an expansion to include coverage of child care and integration into preservice training curricula of all cadres of PHC clinicians.

Plans for further evaluation

A more extensive and robust evaluation is required to measure the immediate, medium-term and long-term impact of the PACK Nigeria programme. This should include an economic evaluation to explore outcomes such as changes in polypharmacy and ordering inappropriate tests, quantifying the impact of PACK on both state health budgets and out-of-pocket expenses to patients. In due course, when the PACK Nigeria programme is scaled-up, a study to assess its impact on important health outcomes should be performed.

Conclusion

PACK Nigeria represents the first single, comprehensive guide that, drawing on applicable national guidelines, integrates the roles of all cadres of clinicians at PHC level in Nigeria. Its development was achieved over a short period through a unique process of remote mentorship of a multidisciplinary clinical team in Nigeria by PACK developers in South Africa.

Extensive and ongoing stakeholder engagement before and during the localisation process played a crucial role in ensuring that, despite some gaps in medication and test availability, the programme enjoyed high levels of acceptance across cadres and geographies and was successfully implemented in all pilot facilities, reflecting local clinicians’ need for up-to-date comprehensive clinical guidance that is user-friendly and responsive to their requirements.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the junior community health extension workers, community health extension workers, community health officers, nurses, midwives, doctors and health managers and chief executives who supported the implementation of the PACK Nigeria programme across the pilot states. Dr Helen Unuareokpa consulted for Health Resources International West Africa during the localisation of the guide, and we acknowledge her contribution. This initiative to pilot PACK was sponsored by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) and the three pilot states, supported by Oxford Policy Management (OPM) and World Bank Nigeria. The leadership provided by the executive chairmen of the primary healthcare development agencies in Adamawa (Dr Mohammed Belel) and Nasarawa (Dr Mohammed Adis), and board executive secretary in Ondo (Dr Francis Akanbiemu) and their teams was invaluable for the successes recorded. It must be noted that without the assistance of World Bank Nigeria, there would have been no pilot.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: CS led on engagement between BMJ, KTU, OPM and Nigerian authorities, and recruited JA as the in-country lead. AA and CJR provided content and training mentorship from the KTU with oversight by RVC and LF. TE provided overall support on engagement and project management. PA oversaw the activities of the HRI team (IU, U-OE, OA and TSE) under JA’s leadership. AD, RC and AA assisted with the monitoring and evaluation with support from LF and EB. AA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed intellectual content, edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: The PACK Nigeria pilot was funded through the Nigerian State Health Investment Project (NSHIP). This is a World Bank-assisted initiative led by Nigeria's NNPHCDA that uses a performance-based financing approach to drive improvements in the quality of care in primary health centres in Adamawa, Nasarawa and Ondo states. It has subsequently been extended to cover five other states in north-eastern Nigeria. The localisation of the PACK Nigeria guide and training resources was funded through a central NSHIP technical assistance budget managed by Oxford Policy Management. The implementation of the pilot at the state level was paid for by each state out of their own NSHIP budget.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that AA, CJR, RVC, LF, EB, AD, RC are employees of the KTU. TE is a contractor for both KTU and BMJ, London, UK. EB reports personal fees from ICON, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Menarini, ALK, Sanofi Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca and grants for clinical trials from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann le Roche, Actelion, Chiesi, Sanofi-Aventis, Cephalon, TEVA and AstraZeneca. All of EB’s fees and clinical trials are for work outside the submitted work. EB is also a member of Global Initiative for Asthma Board and Science Committee. Since August 2015, the KTU and BMJ have been engaged in a non-profit strategic partnership to provide continuous evidence updates for PACK, expand PACK-related supported services to countries and organisations as requested and where appropriate licence PACK content. The KTU and BMJ cofund core positions, including a PACK Global Development Director (TE) and receive no profits from the partnership. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry. This paper forms part of a collection on PACK sponsored by the BMJ to profile the contribution of PACK across several countries towards the realisation of comprehensive primary healthcare as envisaged in the Declaration of Alma Ata during its 40th anniversary.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Nigerian National Health Research and Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. United Nations DoEaSA, Population Division World population prospects: the 2017 Revision, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organisation WHO country cooperation strategy at a glance. Nigeria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health National health policy 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chinawa J. Factors militating against effective implementation of primary health care (PHC) system in Nigeria. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 2015;8:5 10.4103/1755-6783.156701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Federal Republic of Nigeria Nigeria health workforce profile as of december 2012. Nigeria: Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization Working together for health: World Health Report 2006, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health Draft country report, quality of services assessment and resource tracking studies in nigeria (Phase 1). Nigeria: Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Federal Ministry of Health Task-shifting and task-sharing policy for essential health care services in nigeria 2014.

- 9. Charyeva Z, Oguntunde O, Orobaton N, et al. . TAsk shifting provision of contraceptive implants to community health extension workers: results of operations research in northern nigeria. Glob Health Sci Pract 2015;3:382–94. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akinyemi RO, Owolabi MO, Adebayo PB, et al. . Task-shifting training improves stroke knowledge among Nigerian non-neurologist health workers. J Neurol Sci 2015;359:112–6. 10.1016/j.jns.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gureje O, Abdulmalik J, Kola L, et al. . Integrating mental health into primary care in Nigeria: report of a demonstration project using the mental health gap action programme intervention guide. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:242 10.1186/s12913-015-0911-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cornick R, Picken S, Wattrus C, et al. . The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide: developing a clinical decision support tool to simplify, standardise and strengthen primary health care delivery. Submitted to BJM Global Health as part of the PACK Collection 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zwarenstein M, Fairall LR, Lombard C, et al. . Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2011;342:d2022 10.1136/bmj.d2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsima BM, Setlhare V, Nkomazana O. Developing the botswana primary care guideline: An integrated, symptom-based primary care guideline for the adult patient in a resource-limited setting. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:347–354. 10.2147/JMDH.S112466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wattrus C, Zepeda J, Cornick R. Using a mentorship model to localisethe Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Brazil. BMJ Global Health 2018; In press. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fairall LR, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, et al. . Effect of educational outreach to nurses on tuberculosis case detection and primary care of respiratory illness: pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:750–4. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, et al. . Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;380:889–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fairall LR, Folb N, Timmerman V, et al. . Educational outreach with an integrated clinical tool for nurse-led non-communicable chronic disease management in primary care in south africa: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002178 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simelane M, Georgeu-Pepper D, Ras CJ. The practical approach to care kit(PACK) training programme - scalingup and sustaining support for healthworkers to improve primary care. BMJ Global Health 2018; In press. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cornick R, Wattrus C, Eastman T. Crossing borders: the PACK experienceof spreading a complex health systemintervention across low-income andmiddle-income countries. BMJ Global Health 2018; In press. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria N, CHPRBN National standing orders for junior community health extension workers. Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria N, CHPRBN National standing orders for community health officers/community health extension workers. Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yau M, Fairall L, Mayers P. An electronic clinical decision support tool for primary care - a mixed-methods pilot evaluation of e-PC101. BMJ Global Health 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitchell M, Getchell M, Nkaka M. Perceived Improvement in Integrated Management of Childhood Illness Implementation through Use of Mobile Technology: Qualitative evidence from a pilot study in tanzania 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Pimmer C, Mhango S, Mzumara A, et al. . Mobile instant messaging for rural community health workers: a case from Malawi. Glob Health Action 2017;10:1368236 10.1080/16549716.2017.1368236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]