Abstract

The tuberous sclerosis complex is a rare disease, with autosomal dominant transmission, with multisystemic involvement including ophthalmologic. Retinal hamartomas and retinal achromic patch are the most frequent ocular findings. Other ophthalmic signs and symptoms are relatively rare in this disease.

We describe the case of a young woman with tuberous sclerosis who presented with horizontal binocular diplopia and decreased visual acuity without complaints of nausea, vomiting or headache. She had right abducens nerve palsy, pale oedema of both optic discs and retinal hamartomas. An obstructive hydrocephalus caused by an intraventricular expansive lesion was identified in brain CT.

Observation by the ophthalmologist is indicated in all confirmed or suspected cases of tuberous sclerosis to aid in clinical diagnosis, monitoring of retinal hamartomas or identification of poorly symptomatic papilloedema.

Keywords: cranial nerves, hydrocephalus, neurooncology, retina, neuroopthalmology

Background

The tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) belongs to a group of systemic diseases called phakomatoses, which are characterised by neurological, ophthalmological and dermatological involvement (also called ‘neuro-oculo-cutaneous’ syndromes).1–3

TSC is a rare disease with autosomal dominant transmission. It is caused by mutations in tumour suppressor genes, namely the TSC1 gene encoding hamartin, or the TSC2 gene, which codes for tuberin.1 Hamartin and tuberin have a important role in the inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway controlling cell proliferation. Mutations that condition the loss of function of these proteins are in the genesis of cell proliferation and the formation of benign tumours (hamartomas) that characterise this complex.1 Most of the mutations are de novo and occur in the TSC2 gene.1

TSC is a multisystemic disease that can involve the ophthalmological, neurological, dermatological, cardiac, renal and pulmonary systems. Definitive diagnosis of TSC may be clinical or genetic when pathogenic mutations are found in one of the two genes involved.4

Retinal astrocytic hamartomas are the most frequent ophthalmological manifestation, occurring in more than half of patients with TSC. These tumours are essentially composed of astrocytes (also by blood vessels) and can be classified into three types: (1) Flat lesions are the most common type, which are characterised by poorly defined margins and located near the vascular arcades; (2) Multinodular considered the ‘classic’ hamartomas are elevated more frequently found in the macular or peripapillary areas and present calcification allowing their identification in the B-mode ultrasound and CT of the orbits; (3) Mixed are the rarest of these types, have characteristics of the first two, they are usually flat and with poorly defined margins at the periphery and are elevated in the central area.1 Retinal hamartomas are not exclusive of TSC and have been described in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), retinitis pigmentosa and may appear isolated.5–9

Iris hamartomas, known as Lisch nodules, are characteristic of NF1 and may rarely appear in patients with TSC.6 Other ophthalmological manifestations of TSC are the hypopigmented sectoral lesions of the iris and ciliary body, colobomas of the iris and choroid, angiofibromas of the eyelids, and abducens nerve paresis and papilloedema in the context of an hydrocephalus caused by the growth of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA).1

Case presentation

We present a 33-year-old woman, without family history of TSC, with clinical diagnosis of TSC since 12 years old. A mutation in TSC2 gene was detected later. She had dermatological (facial angiofibromas and subungual fibromas), neurological (SEGA), renal (angiomyolipomas) and pulmonary (lymphangioleiomyomatosis) involvement, and was in period of reduction the dose of levetiracetam because she was considering to get pregnant. She did not take any mTOR inhibitor medication for the same reason.

She presented complaints of reduced visual acuity, horizontal binocular diplopia and right eye (RE) esotropia, for the last 3 days. She denied headache, vomiting or nausea. The neuro-ophthalmological examination revealed: right abducens nerve palsy, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 7/10 in the RE and 8/10 in the left eye (LE), and in the ocular fundus signs of pale oedema of both optic discs and lesions consistent with retinal hamartomas bilaterally.

Investigations

Brain CT revealed multiple small subcortical hypodensities of the cerebral hemispheres compatible with tubes and an intraventricular expansive lesion, obliteration of the cortical grooves of the cerebral hemispheres, as well as dilation of the supratentorial ventricular system in the context of obstructive hydrocephalus.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of hydrocephalus includes several conditions (eg, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IH), intracranial haemorrhage, intracranial epidural abscess, meningioma), however, contextualising the signs and symptoms with the systemic disease, the diagnosis of growing SEGA was the most likely.

Treatment

Removal of subependymal tubers, the intraventricular lesion was completely resected and the anatomopathological study confirmed the presence of a SEGA.

Outcome and follow-up

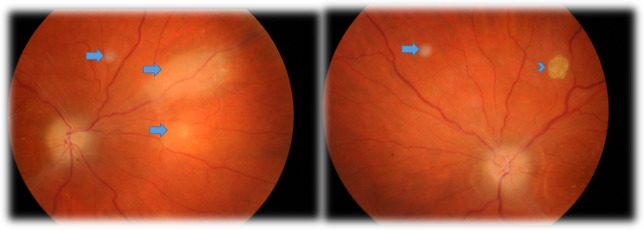

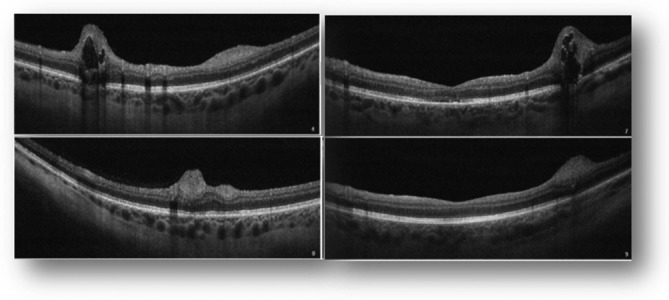

One month after the surgery, the patient had partial recovery of the abducens palsy (some degree of esotropia of the RE, with partial limitation of the abduction of the RE) and slight improvement in visual acuity (BCVA of 8/10 in the RE and 9/10 in the LE). In the funduscopy, she presented pallor of optic discs and of the peripapillary area, poor definition of the limits of both optic discs and lesions consistent with flat and multinodular hamartomas of the retina (figure 1). Optical coherence tomography confirmed the location of hamartomas in the retinal nerve fibre layer, adjacent retinal disorganisation and in some hamartomas the presence of optically empty spaces (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Retinography taken 1 month after surgery, showing pale oedema of both optic discs and retinal lesions consistent with retinal hamartomas (flat lesions (arrows) and a classic multinodular hamartoma (arrow head).

Figure 2.

Macular optical coherence tomography demonstrating retinal disorganisation, lesions located in the retinal nerve fibre layer and optically empty spaces in the two top images (representing the multinodular hamartoma).

Discussion

Retinal hamartomas are benign tumours that result from the proliferation of retinal astrocytes. Hamartomas usually present a non-progressive course.1 In 2005, Shields et al presented four cases, in children between the ages of 1 and 14 years, with TSC with peripapillary astrocytic retinal hamartomas that presented an ‘aggressive behaviour’ characterised by persistent growth, development of exudative retinal detachment, neovascular glaucoma, ocular pain, absence of light perception and that ended in enucleation of the eyeball.10

SEGAs are found in 10%–15% of cases with TSC. These are benign tumours, but by their growth and the development of obstructive hydrocephalus and consequent IH can be a cause of death. Incomplete resection carries a risk of tumour recurrence. The paresis of the abducens nerve occurs in the context of hydrocephalus due to the passage of this nerve through the subarachnoid space.

Ocular manifestations, especially the development of retinal hamartomas, can occur in up to 70% of cases, and ophthalmological observation is indicated in suspected or confirmed cases of TSC.1

In the reported case, correlating the clinical presentation (decreased bilateral visual acuity, absence of headache, nausea or vomiting) in a woman with TSC, with the ophthalmological findings (pale papilloedema) make us think that this is a case of IH with subacute or chronic onset due to the slow growth of SEGA.

Learning points.

The present case illustrates the multisystemic involvement of tuberous sclerosis complex in a patient with a pathogenic mutation in the TSC2 gene.

The observation by the ophthalmologist is important to aid in the clinical diagnosis of the disease (retinal hamartomas constitute a major criteria), and to monitor the evolution of hamartomas (some show a slow and persistent growth, which may lead to the absence of light perception) as well as the diagnosis of little symptomatic papilloedema (subacute or chronic onset) that can be life-saving.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the mentioned authors had an active contribution in the realisation of this paper. Specifying by author: TM was involved in the reporting, conception and design, acquisition and interpretation of data. JL was involved in the planning, conduct and revision of the paper. JM was involved in the planning, acquisition of data and revision. FS was involved in the reporting, interpretation of data and revision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hodgson N, Kinori M, Goldbaum MH, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations of tuberous sclerosis: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2017;45:81–6. 10.1111/ceo.12806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thavikulwat AT, Edward DP, AlDarrab A, et al. Pathophysiology and management of glaucoma associated with phakomatoses. J Neurosci Res 2018;00:1–13. 10.1002/jnr.24241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northrup H, Krueger DA. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 iinternational tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol 2013;49:243–54. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wataya-Kaneda M, Seyama Y, Nihigori CH, et al. Revised tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines. Jpn. J. Dermatol 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinori M, Hodgson N, Zeid JL. Ophthalmic manifestations in neurofibromatosis type 1. Surv Ophthalmol 2018;63:30126–1. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinori M, Moroz I, Rotenstreich Y, et al. Bilateral presumed astrocytic hamartomas in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Ophthalmol 2011;5:1663–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loukianou E, Kisma N, Pal B. Evolution of an astrocytic hamartoma of the optic nerve head in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa - photographic documentation over 2 years of follow-up. Case Rep Ophthalmol 2011;2:45–9. 10.1159/000324037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bec P, Mathis A, Adam P, et al. Retinitis pigmentosa associated with astrocytic hamartomas of the optic disc. Ophthalmologica 1984;189:135–8. 10.1159/000309399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shields CL, Say EAT, Fuller T, et al. Retinal astrocytic hamartoma arises in nerve fiber layer and shows "moth-eaten" optically empty spaces on optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1809–16. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shields JA, Eagle RC, Shields CL, et al. Aggressive retinal astrocytomas in four patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2004;102:139–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]