Abstract

Pioneering strategies like WHO’s Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) have resulted in substantial progress in addressing infant and child mortality. However, large inequalities exist in access to and the quality of care provided in different regions of the world. In many low-income and middle-income countries, childhood mortality remains a major concern, and the needs of children present a large burden upon primary care services. The capacity of services and quality of care offered require greater support to address these needs and extend integrated curative and preventive care, specifically, for the well child, the child with a long-term health need and the child older than 5 years, not currently included in IMCI. In response to these needs, we have developed an innovative method, based on experience with a similar approach in adults, that expands the scope and reach of integrated management and training programmes for paediatric primary care. This paper describes the development and key features of the PACK Child clinical decision support tool for the care of children up to 13 years, and lessons learnt during its development.

Keywords: public health, child health, health systems, paediatrics, practice guidelines as topic

Summary box.

Child mortality has significantly improved, yet in 2015, 5.9 million children under 5 years died, mostly from preventable conditions.

WHO’s Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) strategy, scaled up across low-income and middle-income countries has undoubtedly contributed to significant reductions in under-five mortality and morbidity, but gaps remain: the child over 5, long-term health conditions and well-child care.

The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) Child guide has the potential to expand on the gains of IMCI by blending preventive and curative care and providing algorithmic approaches to symptoms and long-term health conditions for the child from birth up to 13 years.

PACK Child has the capacity to clarify clinician scope of practice and referral prompts to facilitate task sharing and expansion of the team of primary care clinicians delivering child care.

Current landscape of primary care for children

The three overarching objectives of the 2016–2030 Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health are Survive, Thrive and Transform.1 These align with the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals,2 which envisage the highest standards of physical and mental well-being for these vulnerable groups. Healthcare, and specifically universal access to care, is intrinsic to achieving these goals. However, large inequalities exist in access to and the quality of care provided in different regions of the world.3 In many low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), childhood mortality remains a major concern, and the needs of children present a large burden on primary care services. Innovative approaches are required to improve the capacity of services and quality of care offered.4

For the last 20 years, primary healthcare for children under 5 years in LMICs has been shaped by the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) strategy, developed by WHO in collaboration with Unicef.5 6 The strategy pioneered a syndromic approach to the sick child and uses an integrated case management approach to promote timely administration of life-saving empirical treatments based on a classification system rather than diagnoses. The generic IMCI guideline requires adaptation for in-country needs, often with external technical assistance, and training involves an intensive, 11-day, skills-based course. Implemented in over 100 LMICs,7 a foremost consideration in its development was the need to address the skills gap among frontline health workers in managing common childhood illnesses by providing a practical, easy-to-follow algorithmic approach to case management.8–11

The results achieved with IMCI and lessons learnt are reported in several reviews, surveys and multicountry evaluations.10 12–17 Implementation challenges include inadequate local adaptation and infrequent revision of the guideline, insufficient staff training and supervision, patchy uptake and inconsistent use of the guideline in primary care facilities. In response, the programme incorporated a section on neonates, occasional updating, greater use of the syndromic approach, a focus on antibiotic stewardship, revised training and supervision methods, community health worker involvement and health system coordination.12 There remain aspects that are not addressed: guidance for children 5 years and older, management of chronic diseases, and more complete integration of curative and preventive measures, including care of the well child. Furthermore, there is a need for mentoring of clinicians in LMICs to adapt and regularly update the guideline to ensure it remains relevant, and for a training programme that ensures continuous learning, in response to the frequent changes in content in such ‘living’ documents.

Over the past 18 years, the Knowledge Translation Unit (KTU) of the University Cape Town Lung Institute (South Africa), a health systems intervention unit, has investigated and developed evidence-informed methods to strengthen primary care service delivery in underserved communities. The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) Adult programme was designed to support health workers to deliver policy-aligned, comprehensive and integrated primary care for adult patients.18 19 The programme comprises four pillars: (1) a clinical decision support tool (the PACK guide),20 (2) a training strategy,21 (3) a primary care health system strengthening component and (4) monitoring and evaluation.

PACK and its predecessors have been implemented, scaled up and sustained across South Africa, with over 30 000 health workers trained since 2007. Four pragmatic randomised controlled trials evaluating these interventions showed modest but consistent improvements in quality of care, health outcomes and healthcare use,22–25 with parallel qualitative evaluations reporting improved job satisfaction, work morale and a sense of empowerment.26 27

The PACK training strategy, described in detail in another paper in this Collection, employs three key elements that allow for sustainable scale-up21: an educational outreach training,28 a cascade model of implementation and support delivered by government-employed trainers, and a training methodology underpinned by adult education principles.

The KTU has mentored the in-country localisation29 of PACK Adult and its precursors in Botswana,30 Malawi,31 Brazil,32 Nigeria33 and Ethiopia.34

Strong motivation for developing a version of PACK for children came from doctors and nurses who use PACK Adult daily in public sector primary care, and from paediatricians who recognised the need to improve primary care services both to ensure greater access to quality primary care for children and encourage more appropriate referral patterns to higher levels. Both pointed to the need for an expanded scope of practice including children up to the age of 13 years. This paper describes the development of the first pillar, the PACK Child guide, its key features and lessons learnt during its development.

Importantly, the PACK guide is not a text book but rather a clinical decision support tool designed for point-of-care use during clinical encounters. Although broadly falling under the umbrella term of clinical practice guidelines, the term ‘guide’ is preferred to distinguish it from ‘guidelines’ developed with standard evidence-based methodologies.20 The terms ‘clinician’ and ‘user’ of the PACK guide describe a healthcare professional who manages patients in a primary care setting. This may include several cadres of staff; doctors, nurses and, in some settings, physician assistants and community-extension health workers. ‘Local’ and ‘localisation’ refer to the context or region for which the guide was developed, in this instance, for the primary care clinics of Western Cape Province, South Africa.

Objectives in developing PACK Child guide

We aimed to provide a guide with the following features: modelled on experience gained in the development of PACK Adult; suitable for use during primary care clinician consultations with children from birth up to 13 years; comprehensive in its coverage of reasons for attendance; fully integrated to enable cross-referencing for comorbidities; evidence-based, up to date, and in both book and electronic form.

Development process

The steps in the development of PACK Child were similar to those used for PACK Adult and drew on relevant elements from international norms and standards for trustworthy guideline development.20 35 36 The decision to develop the PACK Child guide in one province was based on experience in developing the PACK Adult guide; that close and sustained engagement with expert contributors and clinicians in one region provides a workshop for developing algorithms and checklists, capturing the phronesis that underpins the delivery of clinical care. This experience captured in the first version of PACK Child will be carried over into more generic versions of the guide.20

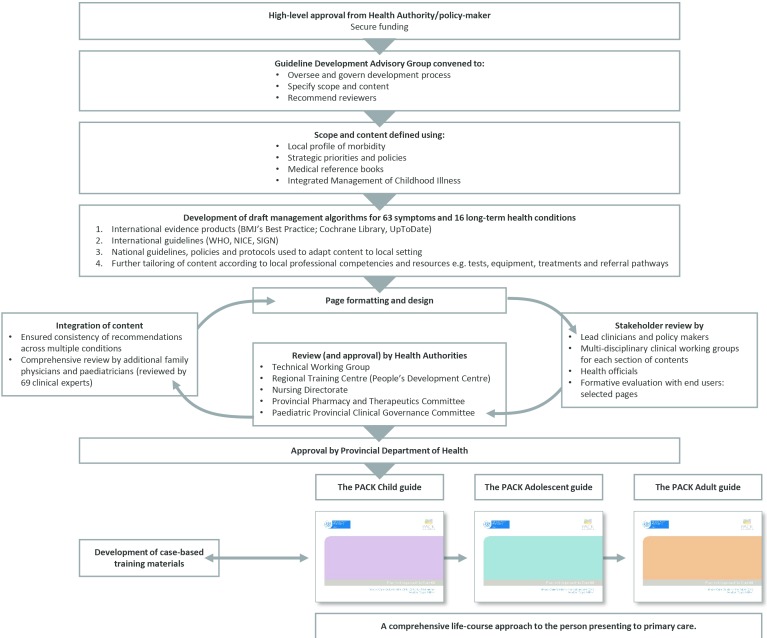

Development began January 2015 and the first version was completed in December 2017. Steps in development are presented in figure 1 and included the following:

Figure 1.

Steps in the development of the PACK Child clinical decision support tool. NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

High-level approval, funding and formation of a Guideline Development Advisory Group

The first step was to obtain high-level policy-maker endorsement and support for the project from the jurisdiction for which it was intended, the Western Cape government. The Western Cape Department of Health appointed members to form a Guideline Development Advisory Group (GDAG). This group comprised local child health clinicians (primary care physicians, paediatricians, nurses) and policy-makers who oversaw and guided the 2-year development process, assisted in defining the scope and content of the guide, and facilitated collaboration with potential peer reviewers. A specialist in the National Department of Health Child and Youth Health Directorate attended the first GDAG meeting and followed the development process.

Funds for the project were obtained from The Children’s Hospital Trust, an independent public benefit organisation that supports the delivery of healthcare for children, primarily through the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital. In 2011, the Trust expanded its fundraising reach to other levels of health services. No funding from commercial enterprises, including pharmaceutical companies, was accepted.

Ethics approval was not required for the development process, as it was not conducted as part of a research study.

Confirming the scope and content of PACK Child

When deciding on the scope of PACK Child, the GDAG considered the opinions, knowledge and experience of local clinicians, available child morbidity statistics in the Western Cape, as well as findings from a cross-sectional survey of reasons for paediatric primary care encounters across four provinces in South Africa, performed in 2010.37 The scope of content of the South African Standard Treatment Guidelines was also considered.38 Consensus decision-making led to PACK including approaches to 63 common symptoms and 16 priority long-term health conditions and that it should be directed towards children from birth up to age 13 (table 1). This content set is largely generalisable to most primary care settings although additional or adapted content is likely to be needed to address local disease profiles when localising for other settings.

Table 1.

Comparison of the content of PACK Child and 2014 South African version of IMCI,39 arranged according to page sections in PACK Child

| PACK Child | Covered in IMCI | PACK Child | Covered in IMCI |

| Symptom pages | Routine care pages | ||

| Assess and manage child’s fluid needs | Yes | Help baby breathe at birth | Yes |

| Manage glucose | Yes | Assess and interpret growth | Yes |

| Fever | Yes | First assessment of the newborn | Limited |

| Pallor or anaemia | Yes | Baby <2 months old: routine care | Limited |

| Wheeze | Yes | Child ≥2 months old: routine care | Limited |

| Diarrhoea | Yes | Screen the child in the prep room | No |

| Seizures/fits | Limited* | Routine visit (schedule) | No |

| Eye/vision symptoms | Limited | Long - term health condition pages | |

| Ear symptom/difficulty hearing | Limited | Breast feeding | Yes |

| Mouth and throat symptoms | Limited | Formula feeding | Yes |

| Cough and/or breathing problems | Limited | Eating | Yes |

| Jaundice | Limited | Poor growth in the child <2 months old | Yes |

| Skin symptoms | Limited | The underweight child | Yes |

| Painful skin | Limited | Not growing well/growth faltering | Yes |

| Generalised itchy rash | Limited | Acute malnutrition | Yes |

| Localised itchy rash/itch with no rash | Limited | The child with a close TB contact | Yes |

| Generalised red rash | Limited | Check for TB | Yes |

| Lumps and bumps on skin | Limited | TB: routine care | Yes |

| Crusts, flaky skin and ulcers | Limited | TB medication | Yes |

| The emergency child | No | HIV: diagnosis | Yes |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | No | HIV: routine care | Yes |

| Choking | No | Monitor the child with HIV | Yes |

| Decreased level of consciousness | No | Start ART | Yes |

| The injured child | No | Medication dosing chart | Yes |

| Fracture/s | No | Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV | Yes |

| Bites and stings | No | Eczema | Limited |

| Burns | No | Chronic malnutrition | No |

| The blue child | No | Overweight | No |

| Poisoning | No | The child with a drug-resistant TB contact | No |

| The inconsolable crying/irritable child | No | Post-exposure prophylaxis | No |

| Headache | No | The child with allergy | No |

| The tired or lethargic child | No | Asthma | No |

| Lumps/swellings in neck, axilla or groin | No | Epilepsy | No |

| Nose symptoms | No | Bronchiectasis | No |

| Face symptoms | No | Known heart problem | No |

| Gum/teeth symptoms | No | Chronic arthritis | No |

| Recurrent respiratory symptoms | No | Cerebral palsy | No |

| Abdominal symptoms | No | Down syndrome | No |

| Vomiting/refluxing | No | Life-limiting illness: routine palliative care | No |

| Constipation | No | Charts | |

| Anal symptoms/worms | No | Weight-for-age chart: girls | Yes |

| Genital symptoms | No | Weight-for-age chart: boys | Yes |

| Urinary symptoms | No | Height-for-age chart: girls | Yes |

| Back pain | No | Height-for-age chart: boys | Yes |

| Arm or hand symptoms | No | Weight-for-height charts: girls and boys | No |

| Leg symptoms/limp/walking problems | No | BMI chart: girls | No |

| Foot symptoms | No | BMI chart: boys | No |

| Joint symptoms | No | Weight-for-age chart: cerebral palsy (GMFCS IV) | No |

| Altered skin colour | No | Weight-for-age chart: cerebral palsy (GMFCS V) | No |

| Nappy rash | No | Useful tools for clinicians | |

| Hair and scalp symptoms | No | Protect yourself from occupational infection | No |

| Nail symptoms | No | Protect yourself from occupational stress | No |

| Suspected child abuse/neglect | No | Communicate effectively | No |

| The stressed, miserable or angry child | No | Prescribe rationally | No |

| Behaviour problems | No | Medication dosing tables | No |

| Communication problem | No | Helpline numbers | No |

| Not moving or sitting properly | No | Quick reference chart | No |

| School problems/bullying | No | ||

| Sleep problems | No | ||

| Parenting difficulty | No | ||

ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, Body Mass Index; IMCI, Integrated Management of Childhood Illness; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit; TB, tuberculosis; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System.

*Limited—these topics are covered to a limited extent in the 2014 South African version of IMCI.

A desk review was conducted of current local and international guidelines and online resources for the care of children at primary healthcare level relevant to LMICs. No single resource was found to address the objectives described above or to be suitable for adaptation.

Development of draft management algorithms

Based on the findings of the desk review, selected resources were consulted to develop each management algorithm. These resources included current international clinical practice guidelines from WHO, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, the American Academy of Pediatrics and evidence synthesis products—BMJ’s Best Practice, UpToDate and Cochrane Library reviews. As most of the evidence-based clinical recommendations appearing in these resources were developed primarily for high-income country settings, each recommendation in PACK Child, though evidence-informed, had to pass the tests of availability of resources and feasibility within South Africa. Further tailoring ensured alignment to latest Western Cape health policies and protocols and harmonisation between pages to avoid conflicting advice. Given the extensive use of IMCI in South Africa,15 we ensured close alignment with IMCI content. Table 1 compares the content of PACK Child and the 2014 South African version of IMCI.39

Page formatting and design

Draft pages of the PACK Child guide were prepared, employing the standard PACK book format, layout and colour-coding to improve recognition and ease of use.20

Stakeholder review

Draft pages were subjected to stakeholder review by specialist clinicians, allied health professionals, doctors and nurses working in primary care and school health services, patient advocates and policy-makers during clinical working group sessions, and through individual peer review. Separate clinical working groups considered 10 topics: the well-child assessment, nutrition, respiratory, neurodevelopment, mental health, musculoskeletal conditions, parenting, tuberculosis, HIV and palliative care. In addition, a group of eight primary care social workers reviewed criteria for referral to social services. Consultation with health officials developing clinic stationery for child care ensured alignment of the guide with proposed patient flow processes.

Two ‘super-user’ groups of IMCI-trained nurses trialled two sections of the guide during primary care consultations with children over a 2-week period. Focus groups were held at the end of this period to obtain feedback. A key consideration was whether clinical decision nodes in the algorithms were clear and easy to use. The response was positive and reassuring, prompting only minor adjustments and clarifications. This feedback informed the use of specific terminology, for example, ‘brassy cough’, used to describe a croupy cough, was changed to ‘barking cough’. An example of strongly positive feedback concerned the clarity of recommendations for prescribing an antibiotic.

Once complete, the full guide was sent for review to 69 clinical experts from various disciplines. They were requested to review particular sections within their field of expertise, with special attention to how this was embedded within the whole guide. Following Shekelle et al’s model, an open and systematic process was adopted for receiving and reviewing comments in the form of a database.40 In total, 410 comments were received. None suggested removal of content but rather, refinements. The iterative correspondence with reviewers led to finalisation of the guide within 3 months. This transparent methodology may have provided reassurance to key stakeholders and facilitated their endorsement of the guide.

Approval by health authorities

The final step involved obtaining comments and approval from local health authorities, governance structures and committees. In the Western Cape, approval had to be obtained from a Technical Working Group, which included operational, monitoring and evaluation expertise, the Regional Training Centre for nurses and the Nursing directorate. Furthermore, a comprehensive medicine list was prepared for the Provincial Pharmaceutical and Therapeutics Committee, whose authorisation was required for the use and confirmation of dose, duration and alignment with the South African Essential Medicines List.38 The latter informed decisions on which cadre of clinic staff was authorised to prescribe each medication.

Final approval of the PACK Child guide was obtained from the Paediatric Provincial Clinical Governance Committee and the Head of the Western Cape provincial Department of Health.

Features of PACK Child

The PACK Child guide is a comprehensive, integrated resource that uses familiar design features from PACK Adult,20 such as easy-to-read algorithms and standardised approaches to routine care, to provide a ‘one-stop’ source of guidance for primary care of the child and young adolescent.

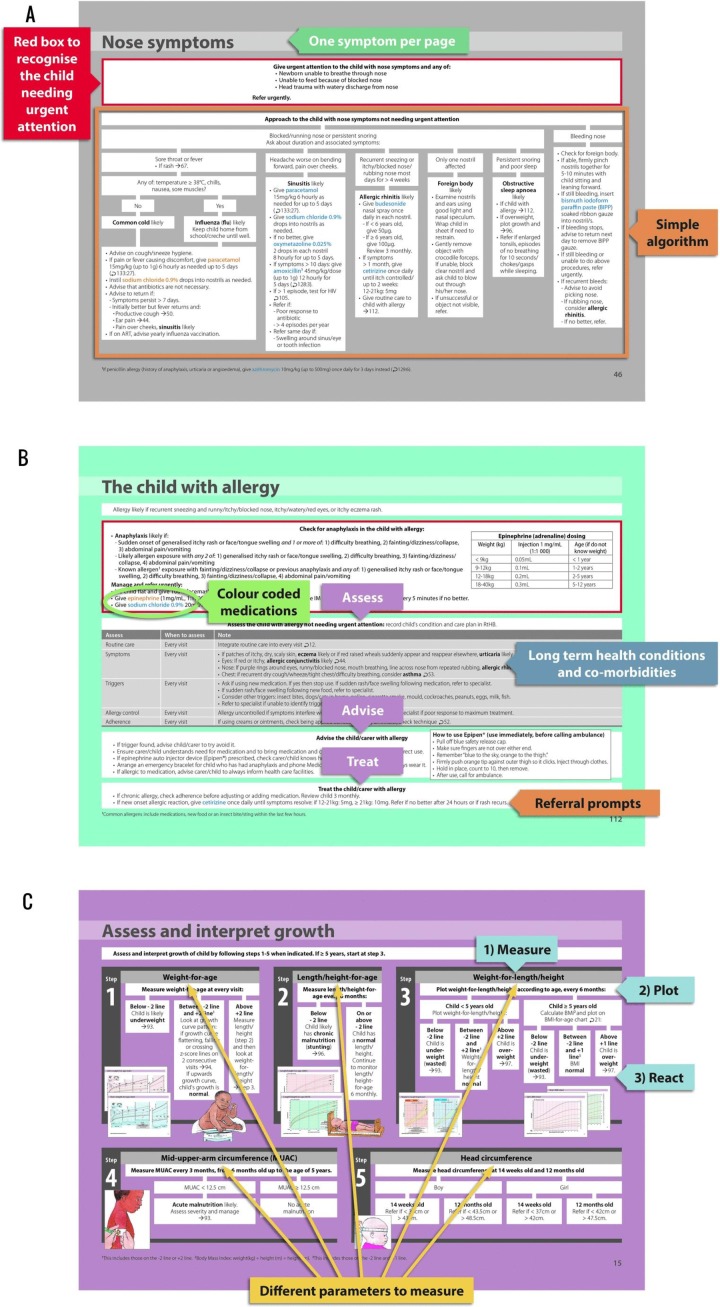

Figure 2 showcases examples of the various formats of PACK Child pages: symptom-based approach (figure 2A), standardised approach to routine care (figure 2B) and step-by-step illustrated guidance (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) Example of a symptom-based approach page. Each symptom is arranged on its own page with a ‘red box’ prefacing a simple algorithm. The ‘red box’ identifies and directs care for the child who needs urgent attention and referral to another level of care. For the child not requiring urgent attention, an algorithm directs the health worker to a likely diagnosis and provides primary care management as well as appropriate referral prompts where a condition is complex, there has been poor response to initial treatment or there is any doubt about a diagnosis. (B) Example of a standardised approach to routine care page. Structured approach to the routine care of a child with a long-term health condition: what to ‘assess’ and when, what to ‘advise’ the carer and child, and how to ‘treat’ the condition. The page also illustrates how PACK Child promotes the recognition of possible comorbid conditions. Three tones of grey in the ‘assess’ table delineate history, examination and investigations. (C) Routine care of the child is integrated into every visit. Growth is emphasised in the routine preventive care section with step-by-step, illustrated guidance on measuring, plotting, interpreting and reacting to growth parameters. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Prompts for recognising children requiring urgent or elective referral are designed to encourage efficient use of services, and timeous access to higher levels of care. Indications, pathways and timeframes are clearly specified.

Medications are colour-coded according to prescriber, which may differ by indication. For example, prednisone appears in three different colours in the guide; a single dose may be prescribed by an IMCI-trained nurse for urgent treatment of croup-related stridor, a nurse practitioner or doctor may prescribe a 5-day course for an asthma exacerbation and only a doctor may prescribe prednisone for a child with Bell’s palsy.

It is hoped that PACK Child will improve the delivery of primary care for children by:

Providing an extended scope of content (table 1) including the needs of children over 5 years old.

Actively guiding the clinician to integrate curative and preventive care at every visit.

Offering an approach for the well-child visit.

Allowing for the management of multiple presenting symptoms.

Providing an approach for routine care of long-term health conditions.

Facilitating task sharing by clarifying roles and responsibilities, referral criteria and prescribing levels.

Similarities and differences of PACK and IMCI

Table 2 uses clinical scenarios to practically demonstrate how the PACK features intend to reinforce the approach of IMCI and build on its limitations.

Table 2.

Clinical scenarios illustrating alignment and differences between IMCI24 and PACK Child guides arranged according to six key features of child healthcare

| 1 | IDENTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE SICK CHILD | ||

| Example: 2-year-old child presents with signs and symptoms of severe pneumonia—worsening cough and difficulty breathing for 4 days. Now with lower chest indrawing. | |||

| Management steps | IMCI | PACK Child | Comments |

| Check for danger signs | Yes | Yes | This clinical scenario aims to demonstrate that PACK Child management steps align well with IMCI management steps. |

| Assess cough | Yes | Yes | |

| Oxygen therapy | Yes | Yes | |

| Management of wheeze offered | Yes | Yes | |

| Management of stridor offered | Yes | Yes | |

| Pre-referral ceftriaxone | Yes | Yes | |

| Co-trimoxazole therapy | Yes | Yes | |

| Hypoglycaemia management | Yes | Yes | |

| Urgent referral | Yes | Yes | |

| 2 | INTEGRATION OF CURATIVE AND PREVENTIVE CARE | ||

| Example: 18-month-old child presents with 2-day history of diarrhoea. No danger signs. No blood or mucus. No dehydration. No feeding problem. | |||

| Management steps | IMCI | PACK Child | Comments |

| Check for danger signs | Yes | Yes | This clinical scenario aims to demonstrate that PACK Child aims to streamline the use of the guide in response to presenting symptom: Number of pages consulted in IMCI guide to manage this case=23 pages. Number of pages consulted in PACK Child to manage this case=8 pages |

| Assess level of dehydration | Yes | Yes | |

| Give fluid according to level of dehydration | Yes | Yes | |

| Advise when to return immediately | Yes | Yes | |

| Zinc therapy | Yes | Yes | |

| Follow-up of diarrhoea | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess and interpret growth (then check all children for malnutrition) | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess feeding | Yes | Yes | |

| Developmental screen | Yes | Yes | |

| Basic examination | Yes | Yes | |

| Check HIV risk | Yes | Yes | |

| Check TB risk | Yes | Yes | |

| Check immunisation status | Yes | Yes | |

| Symptom screen | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess caregiver health | Yes | Yes | |

| Advice for caregiver at home | Yes | Yes | |

| Vitamin A and deworming, if needed | Yes | Yes | |

| Follow-up for routine child visit | Yes | Yes | |

| Psychosocial risk (like parenting, neglect/abuse and grants) | No | Yes | |

| Mental health (behaviour) | No | Yes | |

| 3 | GUIDANCE FOR THE WELL-CHILD VISIT | ||

| Example: 12-month-old well child is brought for immunisations. | |||

| Management steps | IMCI | PACK Child | Comments |

| Symptom screen | IMCI is designed for use during a sick-child consultation and, while it may integrate preventive care during a curative consultation, it has no formal entry point for the well child between the ages of 2 months and 5 years. IMCI does provide an entry point for the infant <2 months old for a well-baby visit; however, this is limited to a symptom screen, advice for home care and feeding counselling. |

Yes | |

| Feeding screen | Yes | ||

| Assess and interpret growth | Yes | ||

| Developmental screen | Yes | ||

| Assess HIV risk | Yes | ||

| Assess TB risk | Yes | ||

| Assess caregiver health | Yes | ||

| Psychosocial risk | Yes | ||

| Mental health (behaviour) | Yes | ||

| Basic examination | Yes | ||

| Health promotion messages | Yes | ||

| Immunisation, if needed | Yes | ||

| Vitamin A and deworming, if needed | Yes | ||

| Follow-up for routine care | Yes | ||

| 4 | STREAMLINED MANAGEMENT OF MULTIPLE PRESENTING SYMPTOMS | ||

| Example: 3-year-old boy presents with 3-week history of loss of weight and a cough. No danger signs. No respiratory distress. No wheeze. Not growing well. HIV negative. TST positive. | |||

| Management steps | IMCI | PACK Child | Comments |

| Check for danger signs | Yes | Yes | Regardless of multiple possible entry points, in this case, loss of weight, not growing well or cough, PACK guides the clinician to the same management steps. |

| Assess cough | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess for TB | Yes | Yes | |

| Identify TB contact | Yes | Yes | |

| TB investigations (tuberculin skin test, gastric washing, sputum test, chest X-ray, if available) | Yes | Yes | |

| Relieve cough (warm water/weak tea) | Yes | Not included | |

| Advise when to return immediately | Yes | Yes | |

| Ask about diarrhoea | Yes | Symptom screen included on routine care | |

| Ask about fever | Yes | ||

| Ask about ear problem | Yes | ||

| Ask about sore throat | Yes | ||

| Assess and interpret growth (check for malnutrition) | Yes | Yes | |

| Feeding assessment and counselling | Yes | Not included, unless feeding problem | |

| Assess HIV risk | Yes | Yes | |

| Deworming and vitamin A, if needed | Yes | Yes | |

| Arrange follow-up | Yes | Yes | |

| Notify and register in TB register | Yes | Yes | |

| Give TB treatment (dosing tables) | Yes | Yes | |

| Routine follow-up TB | Yes | Yes | |

| Check immunisation status | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess any other problems | Yes | Yes | |

| Check caregiver’s health | Yes | Yes | |

| Step-by-step guidance on how to perform a tuberculin skin test (TST) | No | Yes | |

| Screen for other contacts | No | Yes | |

| Advise about importance of treatment adherence | No | Yes | |

| Advise about TB treatment side effects | No | Yes | |

| Guidance on TB and HIV co-infection (like ART dosage adjustments) | No | Yes | |

| 5 | LONG-TERM HEALTH CONDITIONS—IDENTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT | ||

| Example: 4-year-old boy known with epilepsy has had 3 fits in the last month, lasting 5 minutes each. Not fitting now. No associated illness or fever reported. | |||

| Management steps | IMCI | PACK Child | Comments |

| Prompted to integrate routine care into every visit | No | Routine care itemised in scenario 3 | |

| Check adherence | No | Yes | |

| Check side effects | No | Yes | |

| Check other medication interactions | No | Yes | |

| Review fit diary: assess triggers | No | Yes | |

| Ask about mental health (behaviour) | No | Yes | |

| Ask about school problems | No | Yes | |

| Check development | No | Yes | |

| Advise the caregiver | No | Includes health education and support | |

| Doctor review of medication: | No | Yes | |

| Medication table provided | |||

| When to refer to a specialist | No | Yes | |

| When to follow up routinely | No | Yes | |

| When to consider reducing treatment | No | Yes | |

| 6 | TASK SHIFTING | ||

| Example: 3-year-old girl has a 3-day history of wheeze. This is the 4th presentation for wheeze in 3 months. No danger signs. No respiratory distress. Nocturnal cough. Not on asthma treatment. Growing well. | |||

| Management steps | IMCI | PACK Child | Comments |

| Check for danger signs | Yes | Yes | This clinical scenario demonstrates how PACK Child might empower a nurse to perform additional tasks where she previously referred to a doctor. In this case, task-shifting may include instituting a trial of asthma treatment, screening for triggers and other allergy symptoms, providing advice and education, and demonstrating inhaler techniques. |

| Assess cough | Yes | Yes | |

| Salbutamol via spacer for 5 days | Yes | Yes | |

| Refer non-urgently for assessment | Yes | Prompted later for confirmation of diagnosis | |

| Ask about diarrhoea | Yes | Symptom screen included in routine care | |

| Ask about fever | Yes | ||

| Ask about ear problem | Yes | ||

| Assess and interpret growth (then check all children for malnutrition) | Yes | Yes | |

| Check for anaemia | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess HIV risk | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess TB risk | Yes | Yes | |

| Then check immunisation status | Yes | Yes | |

| Assess any other problem | Yes | Yes | |

| Check the caregiver’s health | Yes | Yes | |

| Vitamin A and deworming, if needed | Yes | Yes | |

| Addresses smoking in house | No | Yes | |

| Excludes TB | No | Yes | |

| Assesses recurrent respiratory symptoms (asthma diagnosis algorithm) | No | Yes | |

| Trial of treatment given: | No | Yes | |

| Corticosteroid inhaler for 2 months | |||

| Step-by-step guidance on inhaler (with spacer) technique | No | Yes | |

| Refer non-urgently for assessment if trial of treatment not effective | No | Yes | |

| Prompts a likely asthma diagnosis if trial effective (non-urgent doctor confirmation within 1 month) | No | Yes | |

| Asthma routine care started | No | Yes | |

| Assesses symptom control | No | Yes | |

| Allergy screen | No | Yes | |

| Adherence screen (inhaler technique assessment) | No | Yes | |

| Advice covers passive smoking, treatment education, recognition of acute exacerbations, trigger avoidance | No | Yes | |

| Annual influenza vaccination | No | Yes | |

| Step-up and step-down corticosteroid inhalers according to symptom control | No | Yes | |

| Prednisone course for acute exacerbations | No | Yes | |

| When to return immediately | No | Yes | |

| When to follow up for routine asthma visit | No | Yes | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IMCI, Integrated Management of Childhood Illness; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit; TB, tuberculosis.

Lessons learnt during the development of PACK Child

The concept of developing a PACK Child guide concerned some stakeholders, particularly around its impact on the use of IMCI, which is firmly embedded in clinics in the Western Cape. However, these concerns abated as development progressed and it became evident that, rather than undermine IMCI, PACK Child built on the foundations of integrated care laid by IMCI.

The clinical working groups noted system issues relating to IMCI implementation: in many Western Cape facilities, one IMCI-trained nurse was responsible for managing almost all children attending that facility. This sometimes limited the capacity of the clinic to offer care, further exacerbated by the uneven distribution of staff and curative and preventive care services across the region. This in turn was reported to influence referral patterns to doctors and hospitals. The hope was expressed that by training all categories of clinician in the care of children together, capacity might be increased and referral patterns improved. This inclusive approach to training ensures team members in the same clinic are aware of the others’ roles and responsibilities and may help facilitate task sharing between nurses and doctors. The inclusive PACK training may also ensure a pharmacist is kept up to date with approved treatments and doses and corresponding prescriber authorisation.

The active involvement in the development of PACK Child of primary care doctors and nurses who often see around 60 children per day in stressful conditions served to sharpen recommendations on the basis of feasibility, in many instances tempering the advice and opinions of specialists. This highlighted the practical challenge of successfully integrating preventive services into curative consultations and resulted in further refinement of the routine care pages and influenced the structure of the PACK Child training curriculum.

The development process also highlighted the dearth of recommendations for the adolescent, especially for young girls seeking sexual and reproductive health services, which constitute many primary care attendances.37 The consensus among reviewers, however, was that contraception or termination of pregnancy did not belong in a child guide and that there was a need for a PACK Adolescent guide.

Next steps for PACK Child

The next step for PACK Child is pilot testing in selected clinics in the Western Cape, accompanied by a process evaluation to record the experiences of clinicians who use the guide in routine daily practice, and of patients and caregivers. Major goals of this evaluation are to explore the articulation of PACK Child and IMCI in clinical practice, that is, to ensure that the outcomes expected of IMCI are achieved with PACK Child, and how the PACK training approach should be designed to help and encourage clinicians to integrate preventive and curative care in one consultation. The protocol for this study is described elsewhere and will inform changes to the guide and training programme.41Thereafter, we plan to perform a large pragmatic randomised controlled trial in over 20 clinics to assess the effectiveness and impact of PACK Child implementation, one component of which will be a comparison of the performance of PACK and IMCI in intervention and control clinics, respectively. It is hoped that these evaluations will establish whether the PACK Child programme may be considered an alternative to IMCI in some health systems, offering comprehensive coverage for the needs of children attending clinics.

The PACK Child programme will be a valuable addition to the suite of PACK tools that may be used side by side in clinics in LMICs, articulating with PACK Adult, and, in advanced stages of development, PACK Adolescent, PACK Community (for community health workers) and PACK Information (for patients). This PACK suite of tools aims to provide a continuum of care throughout the lifespan and support important concepts like the maternal-child dyad and the First 1000 days initiative.42 43

Conclusion

Completion of the first version of the PACK Child guide promises to be a step towards better equipping clinicians in primary care to handle the pressing and varying needs of children aged 0 up to 13 years. It builds on experience of a similar approach for adult patients in which its comprehensive scope, thorough integration, symptom-based approach and easy-to-use algorithms providing step-by-step guidance for the clinicians, allows a broad range of health workers to access appropriate information to optimally manage their patient with task-sharing between doctors and nurses.20 26 27 As for all versions of PACK, regular revision provides a current curriculum for continuous learning. Whether PACK Child realises its potential of filling the care gaps in services for children and young adolescents and improves the quality and organisation of care needs to be thoroughly tested in pragmatic studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the more than 198 nurses, doctors, managers and allied health professionals who gave inputs into the development of the guide. In particular, we wish to acknowledge our graphic designer Pearl Spiller for layout, Izak Vollgraaff for the illustrations and members of our Guideline Development Advisory Group: Mark Richards, Elmarie Malek, Lyn Wilkinson, Aletta Haasbroek, Jaco Murray, Sonia Botha, Sikhumbuzo Gangala, Shariefa Patel-Abrahams, Lenny Naidoo and Janet Giddy. And lastly, we would like to acknowledge the KTU Training and Implementation team for driving the next steps in the PACK Child journey.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: SP wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed intellectual content, edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: Development of the PACK Child Guide was funded by a grant from The Children’s Hospital Trust. Additional funding was provided by the University of Cape Town Lung Institute. TD’s time was supported by the South African Medical Research Council. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that SP, LF, EB, CW and RC are employees of the KTU. JH is an ex-employee of the KTU. TD is an employee of the South African Medical Research Council. EB reports personal fees from ICON, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Cipla, Menarini, ALK, ICON, Sanofi Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca, and grants for clinical trials from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann La Roche, Actelion, Chiesi, Sanofi-Aventis, Cephalon, TEVA and AstraZeneca. All of EB’s fees and clinical trials are for work outside the submitted work. EB is also a Member of Global Initiative for Asthma Board and Science Committee. Since August 2015, the KTU and BMJ have been engaged in a non-profit partnership to provide continuous evidence updates for PACK, expand PACK-related supported services to countries and organisations as requested, and where appropriate license PACK content. The KTU and BMJ co-fund core positions, including a PACK Global Development Director, based in the UK, and receive no profits from the partnership. This paper forms part of a Collection on PACK sponsored by the BMJ to profile the contribution of PACK across several countries towards the realisation of comprehensive primary health care as envisaged in the Declaration of Alma Ata, during its 40th anniversary. Each paper in this collection has been peer reviewed.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data is available.

References

- 1. New York Every Woman Every Child Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030) : Every woman every child. New York: Survive, thrive, transform, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Resolution A.70/L.1. Resolution A.70/L.1 United Nations General Assembly, New York, 18 Sep 2015 : Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) Levels & trends in child mortality: Report 2017, estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York: United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simon JL, Daelmans B, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. Child health guidelines in the era of sustainable development goals. BMJ 2018;362:bmj.k3151 10.1136/bmj.k3151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gove S. Integrated management of childhood illness by outpatient health workers: technical basis and overview. The WHO Working Group on Guidelines for Integrated Management of the Sick Child. Bull World Health Organ 1997;75 Suppl 1:7–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization Integrated management of childhood illness: distance learning course. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Victora C, Adam T, Bryce J, et al. Integrated management of the sick child : Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al., Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd edn Washington DC: World Bank, 2006: 1177–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization Improving child health IMCI: the integrated approach. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong Schellenberg J, Bryce J, de Savigny D, et al. The effect of integrated management of childhood illness on observed quality of care of under-fives in rural Tanzania. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bryce J, Victora CG, Habicht JP, et al. Programmatic pathways to child survival: results of a multi-country evaluation of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. Health Policy Plan 2005;20(Suppl 1):i5–i17. 10.1093/heapol/czi055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lambrechts T, Bryce J, Orinda V. Integrated management of childhood illness: a summary of first experiences. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:582–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chopra M, Binkin NJ, Mason E, et al. Integrated management of childhood illness: what have we learned and how can it be improved? Arch Dis Child 2012;97:350–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gera T, Shah D, Garner P, et al. Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) strategy for children under five. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;6:Cd010123 10.1002/14651858.CD010123.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Costello A, Dalglish S. Towards a Grand Convergence for child survival and health: a strategic review of options for the future building on lessons learnt from IMNCI. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fick C. Twenty years of IMCI implementation in South Africa: accelerating impact for the next decade : Padarath A, Baarron P, South African health review 2017. Durban: Health System Trust, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization Integrated management of childhood illness global survey report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goga AE, Muhe LM, Forsyth K, et al. Results of a multi-country exploratory survey of approaches and methods for IMCI case management training. Health Res Policy Syst 2009;7:18 10.1186/1478-4505-7-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fairall L, Bateman E, Cornick R, et al. Innovating to improve primary care in less developed countries: towards a global model. BMJ Innov 2015;1:196–203. 10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. PACK , 2018. Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK). Available from: http://pack.bmj.com/ [accessed July 2018].

- 20. Cornick R, Picken S, Wattrus C, et al. The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide: developing a clinical decision support tool to simplify, standardise and strengthen primary healthcare delivery. BMJ Global Health 2018;3(Suppl 5):e000962 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simelane ML, Georgeu-Pepper D, Ras CJ, et al. The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) training programme—scaling up and sustaining support for health workers to improve primary care. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press:doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fairall LR, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, et al. Effect of educational outreach to nurses on tuberculosis case detection and primary care of respiratory illness: pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:750–4. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zwarenstein M, Fairall LR, Lombard C, et al. Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2011;342:d2022 10.1136/bmj.d2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, et al. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;380:889–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fairall LR, Folb N, Timmerman V, et al. Educational outreach with an integrated clinical tool for nurse-led non-communicable chronic disease management in primary care in South Africa: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002178 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stein J, Lewin S, Fairall L, et al. Building capacity for antiretroviral delivery in South Africa: a qualitative evaluation of the PALSA PLUS nurse training programme. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:240 10.1186/1472-6963-8-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, et al. Implementing nurse-initiated and managed antiretroviral treatment (NIMART) in South Africa: a qualitative process evaluation of the STRETCH trial. Implement Sci 2012;7:66 10.1186/1748-5908-7-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;4:Cd000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cornick R, Wattrus C, Eastman T. Crossing borders: the PACK experience of spreading a complex health system intervention across low and middle-income countries. BMJGlobal Health 2018. In press: doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsima BM, Setlhare V, Nkomazana O. Developing the Botswana primary care guideline: an integrated, symptom-based primary care guideline for the adult patient in a resource-limited setting. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:347–54. 10.2147/JMDH.S112466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schull MJ, Cornick R, Thompson S, et al. From PALSA PLUS to PALM PLUS: adapting and developing a South African guideline and training intervention to better integrate HIV/AIDS care with primary care in rural health centers in Malawi. Implement Sci 2011;6:82 10.1186/1748-5908-6-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wattrus C, Zepeda J, Cornick R, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Brazil. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press: doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Awotiwon A, Sword C, Eastman T, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Nigeria. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press: doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mekonnen Y, Hanlon CFS, Cornick R, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Ethiopia. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press: doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, et al. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:525–31. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ 2014;186:E123–E142. 10.1503/cmaj.131237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mash B, Fairall L, Adejayan O, et al. A morbidity survey of South African primary care. PLoS One 2012;7:e32358 10.1371/journal.pone.0032358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. National Department of Health of South Africa Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list for South Africa: primary health care level. Pretoria: National Department of Health of South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. World Health Organization, UNICEF Integrated management of childhood illness: Department of Health: Republic of South Africa. World Health Organization, UNICEF, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, et al. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci 2012;7:62 10.1186/1748-5908-7-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murdoch J, Curran R, Bachmann M, et al. Strengthening the quality of paediatric primary care: protocol for the process evaluation of a health systems intervention in South Africa. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press: doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. First 1000 Days, 2018. Available from: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/first-1000-days/ [accessed July 2018].

- 43. UNICEF 1000 days, 2018. http://1000days.unicef.ph/ [accessed Jul 2018].