Abstract

Context

Patients with end-stage kidney disease have a high mortality rate and disease burden. Despite this, many do not speak with health care professionals about end-of-life issues. Advance care planning is recommended in this context but is complex and challenging. We carried out a realist review to identify factors affecting its implementation.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are 1) to identify implementation theories; 2) to identify factors that help or hinder implementation; and 3) to develop theory on how the intervention may work.

Methods

We carried out a systematic realist review, searching seven electronic databases: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect.

Results

Sixty-two papers were included in the review.

Conclusion

We identified two intervention stages—1) training for health care professionals that addresses concerns, optimizes skills, and clarifies processes and 2) use of documentation and processes that are simple, individually tailored, culturally appropriate, and involve surrogates. These processes work as patients develop trust in professionals, participate in discussions, and clarify values and beliefs about their condition. This leads to greater congruence between patients and surrogates; increased quality of communication between patients and professionals; and increased completion of advance directives. Advance care planning is hindered by lack of training; administrative complexities; pressures of routine care; patients overestimating life expectancy; and when patients, family, and/or clinical staff are reluctant to initiate discussions. It is more likely to succeed where organizations treat it as core business; when the process is culturally appropriate and takes account of patient perceptions; and when patients are willing to consider death and dying with suitably trained staff.

Key Words: advance care planning, advance directives, kidney failure, chronic, palliative care, realist review, renal dialysis

Introduction

Patients with end-stage kidney disease have a high disease burden and a mortality rate that exceeds age-matched individuals with cancer and cardiovascular disease.1, 2 Renal replacement therapy is life-long treatment to replace the normal function of the kidneys with either chronic dialysis (peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis) or renal transplantation. However, older patients with end-stage kidney disease and additional comorbidities may not achieve improved functional status or live longer on renal replacement therapy. They may be unsuitable for renal transplantation and have complex technical challenges associated with initiating dialysis. Furthermore, some older patients may face the decision of whether or not to even start renal replacement therapy.2, 3, 4 Those who accept renal replacement therapy often experience a range of distressing psychological and physical symptoms.5, 6 Despite this, many do not have conversations with loved ones or clinicians about end-of-life issues such as preferences in relation to admission to intensive care, referral to palliative care services, withdrawal from renal replacement therapy, resuscitation, or where they might choose to die.7, 8 In this context, advance care planning may be a useful intervention to promote shared decision-making among patients, their families, and health care professionals.

Advance care planning is a process aimed at eliciting preferences of patients in relation to future care, including end-of-life preferences.9 It can help patients identify their future health priorities; make an advance decision to refuse a specific treatment (an advance directive); or to appoint someone with lasting power of attorney.10 Advance care planning is associated with considerable benefits in the general population including improved quality of life, decreased anxiety and depression among family members, reduced hospitalizations, increased uptake of hospice and palliative care services, and care that concurs with patient preferences.11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Advance care planning is recommended as good practice for patients with end-stage kidney disease,16, 17, 18 although recent systematic reviews have demonstrated the limited evidence base for the effectiveness of advance care planning in this population.19, 20 Furthermore, advance care planning is a complex process that can provoke cultural and personal sensitivities related to dying11; and uptake is influenced by a range of personal and organizational factors.21 A review of barriers to advance care planning in the general population22 found that implementation was more likely to succeed when advance care planning was embedded in an evaluative research infrastructure, supported by organizational guidance, and part of clinical governance requirements. It was made more difficult when staff lacked time and training, by staff fears around upsetting patients and their relatives, and due to the difficulty of picking the right time for the discussion. Adhering to patients' preferences could be jeopardized by the unpredictability of clinical and organizational factors, and communication difficulties between health care organizations. Given that advance care planning is recommended as best practice in end-stage kidney disease and yet is a complex and challenging process,23 we carried out a realist review of the literature to identify factors that may help or hinder the implementation of advance care planning in this population.

Realist Review

A realist review aims to critically examine the interaction between context, mechanism, and outcome (characterized as context-mechanism-outcome configurations) in a sample of studies of an intervention,24 seeking to establish “what works, for whom, and in what circumstances.”25

Underlying realist reviews are the assumptions of realist evaluation.25 This proposes that an intervention works by changing the context for the people acting within it. Context is defined as “the spatial or geographical or institutional location into which programs are embedded” and “the prior set of social rules, norms, values and interrelationships gathered in these places which sets limits on the efficacy of program mechanisms” (25, P. 70). These “mechanisms” are the reasoning, beliefs, feelings, motivations, and choices of individuals and groups, which lead to patterns of behavior that we recognize as outcomes.26, 27

When an intervention is introduced, it changes the context (by providing further reasoning, opportunities, permissions, legitimations, authorizations, and limitations), so presenting people with a different set of circumstances in which to exercise agency, leading to different outcomes. Of course, this is an interactive process and people will both reproduce and transform their new context, potentially producing a range of outcomes, some of them unintended by those devising the program.

This understanding is neatly summarized by Cheyne et al.:

“A programme comprises multiple elements or components which introduce ideas and/or opportunities for change into existing social systems; the process of how people interpret and act upon these opportunities/ideas are known as the programme's mechanisms.” (28, P1112)

Objectives

The objectives of the review were as follows:

-

1.

To identify the dominant program theories in relation to how advance care planning can be successfully implemented.

-

2.To identify factors that may help or hinder the implementation of advance care planning, with reference to the Consolidated Framework For Implementation Research,29 a pragmatic structure for identifying potential influences on implementation, focused on the following constructs:

-

•The characteristics of the intervention

-

•The outer and inner settings for implementation

-

•The characteristics of the individuals involved

-

•The implementation process

-

•

-

3.

To develop theory based on context-mechanism-outcome configurations to help explain how the intervention may work.

Methods

We followed the RAMESES publication standards for realist syntheses in conducting and reporting our review.24

Scoping the Literature

Before systematically searching the literature, we consulted with patient advocacy groups, health care professionals, and fellow researchers and carried out a rapid survey of systematic reviews, guidance, and policy documents relevant to advance care planning to identify key issues in this area of practice.

Search Methods for the Review

P. O'H and K. N. searched the following databases (from 1960 to 2016) using the relevant search terms or MESH/Thesaurus/Keyword headings for each database: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect. The Medline search terms, which were based on those proposed in a recent Cochrane review protocol,30 are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Strategy for Medline—Modified for Searches in CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect

| 1) exp Advance Care Planning/ 2) (advance care adj (plan or plans or planning)).tw. 3) (advance adj (directive* or decision*)).tw. 4) living will*.tw. 5) Right to Die/ 6) right to die.tw. 7) Patient Advocacy/ 8) ((patient or patients) adj5 (advocat* or advocacy)).tw. 9) power of attorney.tw. 10) ((end of life or end-of-life) adj5 (care or discuss* or decision* or plan or plans or planning or preference*)).tw. 11) Terminal Care/ 12) terminal care.tw. 13) Treatment Refusal/ 14) exp Withholding Treatment/ 15) (treatment adj5 (refus* or withhold* or withdraw*)).tw. 16) 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 17) Renal Replacement Therapy/ 18) renal replacement therapy.tw. 19) exp Renal Dialysis/ 20) dialysis.tw. 21) (hemodialysis or haemodialysis).tw. 22) (endstage kidney or endstage renal or end stage kidney or end stage renal).tw. 23) (ESKD or ESKF or ESRD or ESRF).tw. 24) 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 25) 16 and 24 |

Selection and Appraisal of Documents

Documents were selected based on their relevance for theory building rather than their quality or methodological approach, which allowed us to include a range of literature. We included documents if they addressed advance care planning and end-stage kidney disease. We excluded documents that were not in English as we had no access to translation services. Finally, we excluded documents published before 2000 as we found no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published before this date and the organizational and clinical context was likely to be significantly different for papers published earlier.

Realist reviews include a broad spectrum of studies, but the quality of studies is used to moderate findings. The methodological quality of empirical studies was assessed using the appropriate appraisal tool from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,31 and studies were classified as strong, moderate, or weak in terms of rigor.

Data Extraction

Data were harvested from papers selected for full-text review by five reviewers (P. O'H., K. N., H. N., J. B., and J. C.) using a standardized data extraction form developed for a previous realist review,32 based on the RAMESES publication standards.24 This form included sections related to the realist assessment, requiring the reviewer to seek information on the theoretical background and characteristics of the intervention, how it was thought to work, outer and inner settings for implementation, characteristics of the individuals involved, the implementation process, and the characteristics of the context thought to influence outcomes.

Analysis and Synthesis

Candidate theories were identified through a close reading of texts by two reviewers (P. O'H. and K. N.). Explicit theories were noted, and where absent, implicit theories deduced from the elements of the interventions. Data synthesis involved the two reviewers independently assessing each paper, identifying common components from the data extraction forms, and reflecting on candidate theories before coming together to discuss findings and achieve a consensus regarding the explanatory power of each. All authors then assessed the candidate theories and provided feedback. We privileged empirical papers in our final analysis as these represent studies closest to particular practice contexts.

Results

Study Selection

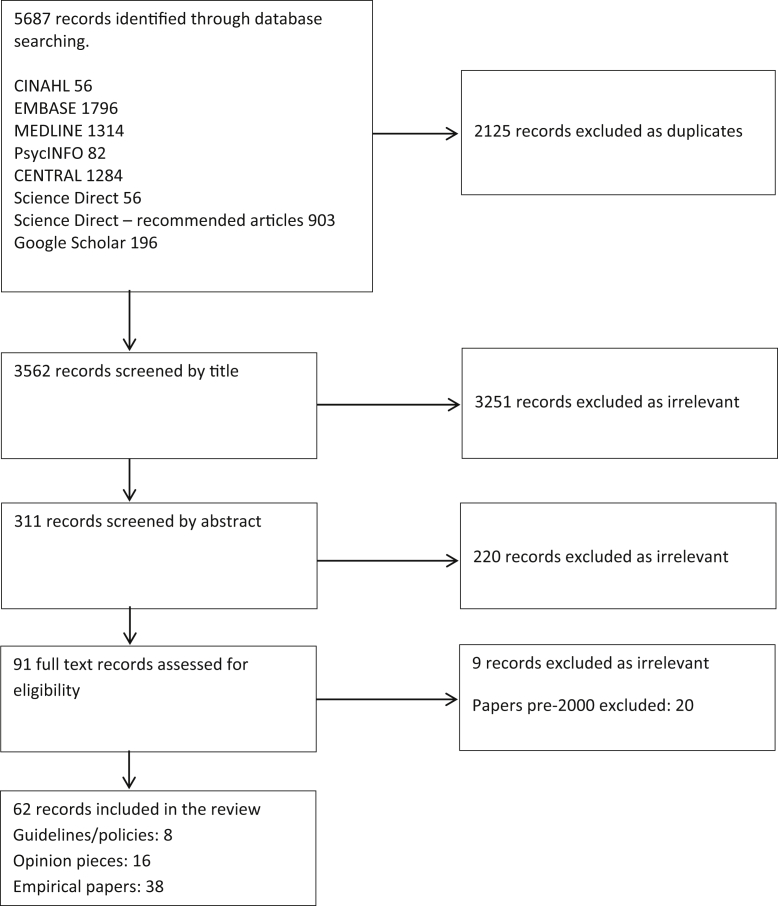

Our initial search of databases produced 5687 documents (Figure 1). Removing duplicates left 3562 documents. Title review looking for documents relevant to advance care planning and end-stage kidney disease by two reviewers (K. N. and P. O'H.) excluded 3251 papers, with abstract review reducing this to 91 papers. The full text of these papers was reviewed by the two reviewers and a decision taken at this stage by the review authors to exclude 20 papers published before 2000 in the interests of organizational and clinical relevance to contemporary practice. This left 62 documents, of which 16 were opinion pieces, eight were guidelines or policies, and 38 were empirical papers that formed the basis of this review.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart illustrating the search process.

Study Characteristics

Study Designs

The 38 empirical studies were of various designs (Supplemental Table 1). Three were literature reviews19, 20, 33; five were RCTs34, 35, 36, 37, 38; and another39 a secondary analysis of an RCT.38 Three were nonequivalent group designs40, 41, 42; one single-group test-retest study43; nine were qualitative studies44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52; and 16 observational studies.53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68

Methodological Quality

Thirteen studies were classified as “strong”19, 20, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 53, 55, 60, 63, 65, including one RCT38; and 10 as “weak”33, 34, 40, 41, 43, 48, 54, 59, 62, 67; with the remaining 14 classified as “moderate.” One paper42 reported a protocol, so a judgment was not made.

Main Objectives of the Studies

Intervention studies sought to evaluate the effect of advance care planning on use of services and on congruence of care at end-of-life with patients' wishes,19, 20, 37 or on congruence between patients and surrogates.34, 36, 38, 39 Other studies focused on interventions to improve uptake of advance care plans,35, 41 or to encourage professionals to support patients in making advance care plans.40, 43 Most of the observational and qualitative studies concentrated on establishing patients' attitudes (or those of professionals55 or family members49) toward death, dying, end-of-life care, discussing treatment preferences, withdrawal of treatment, and making advance care plans or advance directives. Exceptions were those that looked for congruence between advance care plans and clinical outcomes,53 and between surrogates' and patients' views on treatment preferences44, 61; and those that sought to examine the prevalence and contents of advance directives60, 68 to evaluate patient-physician communication about end-of-life care57; to explore the association between advance care planning and withdrawal from dialysis, use of hospice, and location of death59; and to describe how seriously ill patients can be assisted to identify a surrogate.58 Two studies were intended to inform interventions for staff training.48, 51

Study Populations

With the exception of three studies that focused on health professionals40, 55 and family members49, all studies were of patients with end-stage kidney disease, some including family members/surrogate decision-makers, and three including patients with other long-term conditions.34, 37, 41 A minority specified further characteristics for patient inclusion, such as aged over 50 years34; or thought to be at risk of death in the next six42, 1238, or 24 months37; or with significant comorbidity.43

Advance Care Planning Interventions

Three RCTs34, 36, 37 evaluated patient-centered advance care planning: a one-hour interview delivered by a trained facilitator to patients and their surrogates to help prepare surrogates to make decisions that honor the patient's preferences for care, leading to documentation of preferences. Song et al.38 took a similar approach but in two sessions over two weeks. Simon et al.52 a qualitative study, reported an advance care planning process comprising trained facilitators, a workbook with suggestions for levels of intervention, and organizational processes that audit and operationalize advance care planning in medical records and treatment plans. Perry et al.35 used trained peer mentors who had three face-to-face and five telephone contacts with patients over a two- to four-month period.

Outcomes of Advance Care Planning Interventions

The RCT intervention studies showed statistically significant improvements in congruence in statement of treatment preferences,34, 36, 38 surrogate decision-making confidence,38 patient's perceived quality of communication,34, 36 and decisional conflict34; an increase in completion of advance directives; and comfort in discussing them.35 Unexpected results were more intervention patients (37.7%) choosing to withdraw from dialysis than controls (17%)—although this had not been discussed in advance care planning37—and a shift among participants toward using all possible life-sustaining treatments to prolong their lives.36 The non-RCT intervention studies reported that electronic medical record reminders improved advance directive documentation41; that nurses self-reported increased efficacy in relation to upholding patients informed choices40; and that there was no effect on number of advance directives.43 In their review of RCTs or quasi-RCTs, Lim et al.20 reported no effect on hospital admissions or use of treatments with life-prolonging or curative intent or on following patient's wishes at end of life.

Program Theories in Relation to How Advance Care Planning Can Be Successfully Implemented

Luckett et al.19 reflect the broad concept of advance care planning found in most studies when they characterize it as

“ …. a process of reflection, and discussion between a patient, their family and healthcare providers for the purpose of clarifying values, treatment preferences and goals of end-of-life care. Advance care planning provides a formal means of ensuring healthcare providers and family members are aware of patients' wishes for care if they become unable to speak for themselves. Advance care planning is a patient-centered initiative that promotes shared decision-making, which may include the patient completing an advance directive that documents their wishes and/or the appointment of a substitute decision-maker.” (P. 762)

The theory is that once the patient, their family or surrogate, and the health professionals have a common understanding of the patient's preferences for end-of-life care, then they will be more likely to act together to enact those preferences, even if the patient loses capacity. A subtheme is that the patient will be less likely to choose (possibly futile) life-prolonging treatments (such as resuscitation and dialysis) at end of life and more likely to choose palliative care services and hospice care, which will enhance their quality of life until death. These views on the nature and outcomes of advance care planning are reflected in many guidelines and opinion pieces.7, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74

The empirical studies provide more detailed explanations as to how advance care plans may work. Several studies report that the advance care planning process helps to prepare both the patient and the surrogate to make better decisions by helping the patient to clarify values and develop skills related to initiating discussions, and by actively involving the surrogate to help prepare for the emotional burden of decision-making.34, 36, 37, 38, 39 Systematically, eliciting patient preferences for end-of-life care allows concordant care to be provided.42 Other studies focused on the role of professionals, theorizing that addressing concerns about advance care planning, optimizing skills, and clarifying processes will legitimize advance care planning and encourage professionals to initiate discussions.40, 48

Some studies based their approach on previously published theories. Five papers reporting four RCTs34, 36, 37, 38, 39 described attempts to help the patient examine their own belief systems and integrate new information, based on the representational approach to patient education. This seeks to illuminate a person's illness representation—the set of thoughts that a person has about a health problem in five dimensions: identity, cause, timeline, consequences, and cure/control—to provide an opportunity for the person to reflect and to allow the clinician to provide individualized, acceptable information.75, 76, 77, 78 One study66 drew on components of the theory of planned behavior79 to argue that a person who holds strong beliefs about death and dying and has a positive evaluation of advance care planning will more likely have a positive attitude toward making an advance care plan.

Calvin et al.45, 54 developed a new “theory of personal preservation.” Patients on dialysis are thought to experience three phases: a redefined sense of self as they acknowledge a shortened lifespan; a response to this redefinition that asserted their individuality in terms of their resilience in the face of life's challenges, and finding meaning and optimism in their suffering, often through prayer or trusting in God's will; and finally living in the tension of acting responsibly to care for themselves and others, while managing the risks and uncertainty associated with treatment by fallible professionals. They did not see advance care plans as a means to maintain personal autonomy, preferring to leave such decisions to trusted family members, and to focus on negotiating present challenges. This theory (which has elements in common with that of Goff et al.51) is intended to inform communication around advance care planning. Similarly, Simon et al.52 propose a model in which preexisting ideas formed by “witnessing illness in self and others” and “acknowledging mortality” lead to reflection on states of dysfunction in which patients would not want to live. These combine with the advance care planning process to produce a degree of peace of mind in that participants had planned to avoid burdensome states and reduced family stress.

Factors That May Help or Hinder the Implementation of Advance Care Planning

The Characteristics of the Intervention

One review concluded that interventions do not give comprehensive attention to patient, caregiver, health professional, and system-related factors.19 Giving structured feedback to facilitators on their delivery of advance care planning was thought to enhance the process.37, 38 An electronic medical record–based reminder appeared to improve completion of advance directives by prompting discussions within the outpatient visit workflow.41 Tailoring advance directive documentation to patient needs and keeping documents short was thought to encourage completion,63 whereas administrative and legal complexities discouraged completion.58

The Inner and Outer Settings for Implementation

In terms of the inner organizational setting—which includes organizational structure, communications, culture, and capacity for change29—implementation was enhanced by educating staff on the benefits of advance care planning.19 Advance care planning was more likely to be used when staff trained to facilitate appropriate discussions were available,34, 36, 37, 38, 48 when physicians actively recommended hospice care,59 and where there were processes reflecting organizational endorsement such as administrative requirement for advance directives,53 and a policy of providing support for staff education, patient information, and related safety and quality systems.40 Overall, ensuring staff have time for advance care planning as “core business” supported implementation.19

On the other hand, the pressures of (and focus on) routine clinical work,33, 46 a “conveyor-belt” culture in relation to providing hemodialysis,50 lack of funds to support staff training,48 and poor continuity of medical care,57 all militated against uptake of advance care planning.

Turning to the outer setting—which includes external policies and incentives, patient needs and resources, and relationships with other (peer) organizations29—wider cultural differences were reported to exert profound effects on advance care planning processes. In general, it appears that advance care planning is seen as a more normal part of health care in the U.S.—all but one of the intervention studies40 were carried out there. However, within the U.S., patients and families with lower socioeconomic status reported feeling disempowered in interactions with the dialysis team and therefore less likely to build trust and complete advance care plans.51 African Americans were described as more responsive than whites to an intervention that was highly inclusive of family surrogates, as this may align with their familial, religious, and communal frame of reference39 and to be open to peer interventions because of a preference for oral traditions35. Similarly, Asian Americans and Hawaiians (from cultures where family involvement and discussion, and collective decision-making, are important) expressed a preference for discussing advance care planning with family rather than health professionals.66 African and Asian American patients were found to be more likely to engage in end-of-life discussions, but African Americans were less likely to prefer dialysis withdrawal at end of life and to complete a do-not-resuscitate directive.67 In one rural study, reluctance of many patients to travel the necessary distance for tertiary care contributed to the low prevalence of in-hospital death.59

A Saudi Arabian study64 reported that Islam is in principle compatible with advance care planning, but that this was rarely discussed and patients were generally against “do-not-resuscitate” decisions—attitudes echoed in a study in the Republic of Ireland, where it was also reported that advance directives had no legal status, with very few people aware of their existence.56 Miura et al.61 stated that Japanese culture includes the belief that one's wishes are intuitively known to others, leading to an erroneous assumption that family members can correctly predict patient's preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or continuation of dialysis at end of life. Physicians may be paternalistic and families may see withdrawal of treatment as abandoning their duty to the patient, so that the physician defers to the family even against the patient's advance directive, leading to inappropriately aggressive treatment at end of life. Similarly, Yee et al.55 perceive Singaporeans may not be ready for advance care planning, as it can be confused with advance directives (and advance directives with euthanasia) by both health care professionals and patients. The family also plays an important role in health-related decisions and may sometimes disagree with patients' preferences. A Spanish study reported that people are unfamiliar with advance directives and fear that physicians may withhold necessary treatments, leading to low uptake.68 A study in the United Kingdom argued that there is a need for a culture shift from a “disease-focused” model toward a “holistic care-based” approach, normalizing discussions about preferences, priorities, and future care.50

Characteristics of Individuals

A common finding was that patients and their families found it difficult to initiate conversations about future care with professionals, especially nephrologists.19, 45, 49, 51 Patients expected professionals to take the initiative,19, 33, 46, 47 but professionals were reluctant for fear of upsetting patients and families20, 37, 43, 49, 50, 55, 62 and in the case of nurses, upsetting senior staff.19 One study argued that a focus on technology had taken nephrologists away from offering emotional and spiritual support.65

Patients were thought to overestimate their life expectancy19 and to distance themselves from thoughts of death,45, 52 thus reducing their sense of urgency to have advance care planning discussions. Surrogates were often unaware of patients' views and held different positions on care at end of life.19, 44, 55, 61

A trusting relationship with the person proposing advance care planning seemed to make acceptance by the patient35, 51, 56, 68 and family members49 more likely, with lack of trust, making discussions more difficult.

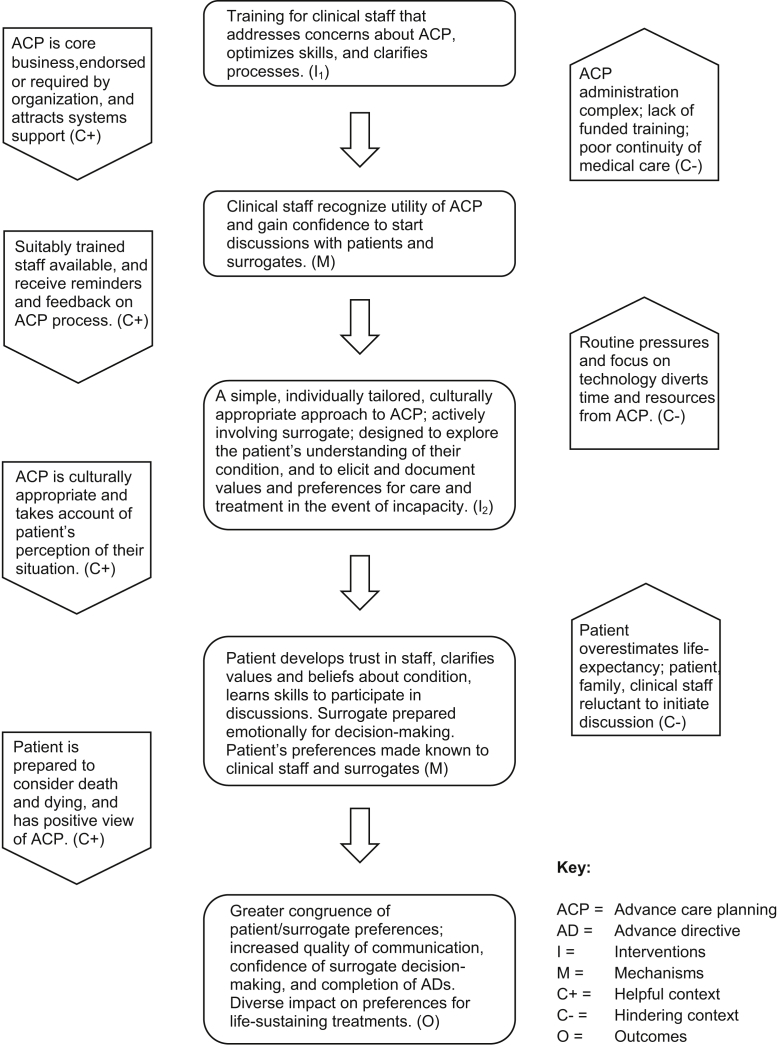

Theory Synthesis

In the following section, we seek to examine the interaction between the intervention (I), context (C), mechanism (M), and outcome (O) in relation to advance care planning, with a view to offering a theory to explain and support implementation (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Model for the implementation of advance care planning with patients who have end-stage kidney disease.

Implementation of advance care planning entails two major intervention stages (I1 and I2). First, there is training for clinical staff that addresses concerns, optimizes skills, and clarifies processes (I1). This helps clinical staff to appreciate the usefulness of advance care planning and to gain confidence to initiate discussions with patients and their surrogates (M). The second stage (I2) is when the advance care planning documentation and processes are implemented. These should be simple, individually tailored, culturally appropriate, and actively involve surrogates. They are designed to explore the patient's understanding of their condition, to elicit what the patient values in relation to their health and relationships, and on this basis to document their preferences for care and treatment in the event of incapacity.

These processes have their effect as patients develop trust in staff, clarify their values and beliefs about their condition, and learn skills to participate in discussions with clinical staff and others. Consequently, patients' preferences are made known to clinical staff and surrogates, and surrogates are prepared emotionally for decision-making (M). These interventions, working through the mechanisms described, lead to greater congruence between patient and surrogate on treatment preferences; increased quality of communication between patients and clinical staff; greater confidence in surrogates about decision-making on patients' behalf; and an increased rate of completion of advance directives. Preferences for life-sustaining treatments may increase or decrease under the influence of the sociocultural context (O).

These outcomes are hindered by a number of organizational issues: lack of funded training opportunities, administrative and legal complexities around advance care planning, the prioritization and pressures of routine care, and a focus on technological (rather than personal and spiritual) aspects of care. Barriers may also arise from interpersonal issues: when the patient overestimates life expectancy and therefore does not appreciate the relevance of discussions about future care; and when the patient, family, and/or clinical staff are reluctant to initiate discussions about treatment decisions in the event of deterioration because of fears of causing distress (C).

On the other hand, advance care planning is more likely to succeed where it is acknowledged as core business and required or endorsed by the organization and therefore attracts resources to support education and quality assurance; when suitably trained staff are available and receive reminders and feedback on implementation; when the process and documentation are culturally appropriate and take account of the patient's perception of their situation; and when the patient is prepared to consider death and dying and has positive view of advance care planning.

Discussion

Most of the included papers (25/38) reported observational or qualitative designs. These provide useful information on the perceptions, attitudes, and behavior of patients, families, and professionals in relation to death, dying, and advance care planning. However, there were only eight intervention studies found, of which five were RCTs, with 593 patients and 390 relative participants. RCT outcomes were diverse, showing statistically significant improvements in the quality of communication and confidence in decision-making, but no effect on hospital admissions or use of treatments with life-prolonging or curative intent, or on following patient's wishes at end of life. Indeed, only one RCT37 attempted to measure whether patients received care in accord with their wishes, and low numbers precluded statistical analysis. No RCTs effectively investigated impact on use of health services, hospital admissions, or treatment, which ruled out any evaluation of cost-effectiveness. Of the RCTs, we judged only one38 to be methodologically strong; the others to be moderate or, in one case, weak.

The commonly held theory that advance care planning will lead to a shared understanding of patient preferences for end-of-life care, and subsequent enactment of those preferences, with less recourse to life-prolonging treatments and greater use of palliative care services and hospice care, is only partially supported by the evidence. One study37 reported that more intervention patients chose to withdraw from dialysis than controls, despite withdrawal not being discussed in advance care planning, but this result should be interpreted with caution as the paper does not specify numbers of participants for this subgroup analysis. Song et al.36 report an increase in preference for life-sustaining treatment in their intervention group, attributing this to cultural and religious mores among their African American sample. Again, a small sample size (n = 19) invites cautious interpretation. It does seem that advance care planning can help clarify preferences and improve communication, but other outcomes remain unsupported or equivocal. These findings are consistent with two recent reviews,19, 20 which concluded that the evidence base is weak in this population.

Unpicking the program theories in relation to how advance care planning could be successfully implemented, and identifying contexts that may help or hinder, has allowed us to synthesize an integrated theory to explain and support implementation. Unsurprisingly, the first stage is staff training. However, it is important to note the focus of the training—to address staff concerns, clarify processes, and optimize skills—and its goal—to persuade staff of the usefulness of advance care planning and to give them confidence to start discussions with patients and their relatives. Training is less likely to be effective if it takes for granted the usefulness of advance care planning, marginalizes staff concerns, and does not engender confidence in the process.

Similarly, when addressing the second stage of implementation (the approach to the patient and relatives), the focus and goal of the approach are key ingredients for success. The advance care planning document and approach should be culturally appropriate, actively involve the surrogate, explore the patient's understanding of their condition, and elicit and document their values and preferences for care. The goal is for the patient (and their surrogate) to trust staff sufficiently that they are able to share their values and beliefs and gain confidence to enter into discussions with clinicians. The few detailed reports of advance care planning interventions largely described relatively short (e.g. one hour) guided interactions between the patient, their surrogate, and a trained facilitator, helping the patient and surrogate to clarify values and develop skills related to initiating discussions, preparing for decision-making, and leading to a document recording patient preferences. One hour is not a long time to spend making a plan for one's care in the event of deterioration, but it is significant in terms of professional time when there are competing priorities. This introduces the impact of context. In organizational terms, the umbrella concept is that advance care planning should be core business. That is, it should attract support in the form of policy, administrative processes, resources (funded training, staffing levels), quality assurance, and accountability. Advance care planning that is an “add-on” is likely to be swamped by the pressures of routine care. Interestingly, only two studies directly addressed organizational issues: one that reported training nurses to offer advance care planning in the context of a supportive policy framework of educative, patient information, safety, and quality systems40; and the other examining the effectiveness of an electronic medical record–based reminder in improving advance directive documentation.41 The vast majority of studies focused on patient-staff interaction in relative isolation from the organizational context.

Surrounding and pervading organizations are the cultural and personal values that heavily influence the responses of both staff and patients to discussions about care at end of life. Advance care planning has largely evolved within Western democracies and been developed by professional elites. Consequently, the approach typically embodies a cultural commitment to individual autonomy, which may sit uneasily with those with lower socioeconomic status, or from cultures, which privilege the family in decision-making. Similarly, professionals may assume advance care planning will entail refusing or curtailing treatment, when patients are inclined to continue and maximize interventions. Added to this is a reluctance on all sides to raise the issues of poor prognosis and death. For these reasons, it is important that the advance care planning process and documentation are culturally appropriate. It should take into account patient and family perceptions of their situation, including life expectancy and the likely efficacy of life-sustaining interventions; religious and cultural understandings of death, dying, and the place of medical care; together with preferences in relation to involvement of the family in decision-making. Given that patients have difficulty in raising advance care planning with professionals, there is a role for patient representative bodies and the charitable sector in educating patients and families in relation to advance care planning and advocating for health care organizations and professionals to take the lead in introducing it to patients.

Strengths and Limitations

Intervention studies were relatively few and often small, which limited our ability to comment on clinical or cost-effectiveness of advance care planning in this population. Other studies had diverse aims and designs, making synthesis a challenge. However, this diversity did serve to provide data on organizational and cultural aspects. Having said that, most studies did not set out to explain how advance care planning might work or to identify helping or hindering factors, which meant the authors had to glean some of these insights from the narrative and discussion sections of the papers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Robust clinical trials are needed in this population to investigate the impact of advance care planning on enactment of patient preferences for end-of-life care; recourse to life-prolonging treatments; and use of palliative care services and hospice care.

Nevertheless, it is evident that for patients with end-stage kidney disease, advance care planning is much more than an administrative or merely intellectual task. On the contrary, it is an intensely human process in which a vulnerable patient is invited to consider their own deterioration and death, and to make plans for navigating various threatening possibilities. Despite this, there is already some evidence of positive outcomes for patients and their families in the form of congruence in statement of treatment preferences, surrogate decision-making confidence, improvements in perceived quality of communication and decisional conflict; an increase in completion of advance directives; and comfort in discussing them. Consequently, professionals have a responsibility to offer advance care planning to patients and to support them during the process. Given the significance and complexity of this task, professionals need organizational support in the form of policy endorsement; quality assurance; administrative systems; training that addresses concerns, optimizes skills, and clarifies processes; and staffing levels that allow time for proper attention to implementation. This will allow them to develop an approach to advance care planning that is designed to explore the patient's understanding of their condition, and to elicit and document values and preferences for care and treatment in the event of incapacity, but is also simple, individually tailored, culturally appropriate, and actively involves surrogates.

Bearing in mind the profound impact of cultural and organizational context, we recommend that patient groups, professionals, and their organizations take a diagnostic approach to their particular situation when implementing advance care planning. In other words, they should consider the beliefs and expectations of the surrounding culture, their own resources, and how they can best organize advance care planning training and implementation to trigger the mechanisms and achieve the outcomes identified in our implementation model. Specific recommendations for stakeholders are offered in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recommendations for the Development and Implementation of Advance Care Planning for Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease

|

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Dunhill Medical Trust [grant number R428/0715]. Dr. Jackie Boylan and Dr. Judith Cole assisted in data extraction for this review.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Appendix

Supplemental Table 1.

Empirical Studies

| First Author, Country, and Objectives | Population, Setting, and Intervention | Design and Methodological Rigor (Strong/Moderate/Weak) | Key Results | How the Intervention Was Thought to Work | Contextual Features Thought to Influence Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic reviews | |||||

| Lim (2016), Australia. Objectives: To determine whether advance care planning in hemodialysis patients, compared with no or less-structured forms of advance care planning, can result in fewer hospital admissions or less use of treatments with life-prolonging or curative intent, and if patient's wishes were followed at end of life. |

Systematic review: RCTs or quasi-RCTs with hemodialysis patients. Intervention: ACP is where the responsible physician helps the patient (with their family) to reflect on their future care, consults the patient on their priorities and preferences and levels of care, manages transition from active to palliative care, and, together with any spokesperson appointed by the patient, acts as an advocate for the patient in the event of incapacity, drawing on the patient's documented preferences. |

Systematic review. Rigor: Strong (comprehensive search strategy and rigorous assessment of study quality). |

Two studies (three reports) that involved 337 participants investigated advance care planning for people with ESKD. Neither of the included studies reported outcomes relevant to the review. Study quality was assessed as suboptimal. The results suggested patients were highly satisfied with the quality of communication and greater levels of comfort. Discussion regarding ACP and end-of-life care did not destroy hope or cause unnecessary discomfort or anxiety to patients. Given the lack of evidence for advance care planning for people receiving hemodialysis, large scale, well-designed RCTs involving people with ESKD are necessary to determine the efficacy and value of advance care planning for patients. |

Aiding patients to establish options and priorities for end-of-life care enables preferences to be maintained according to individual wishes. ACP enables patients to prepare for death, strengthen relationships with loved ones, achieve control over their lives, and relieve burden on others. | The most significant barrier may be lack of physician intervention to initiate and guide advance care planning discussions. |

| Luckett (2014), Australia. Review objectives: 1) To identify what interventions have been developed, piloted, and evaluated. 2) To identify which measures have been used in intervention and other studies. 3) To establish evidence for the efficacy of interventions. 4) To inform understanding of barriers and facilitators to implementation as well as stakeholders' perceptions of ideal approaches. |

Systematic review: Samples had to be adults with a primary diagnosis of CKD and/or families and the health professionals caring for this group. Intervention: ACP was defined as any formal means taken to ensure health professionals and family members are aware of patients' wishes for care in the event they become too unwell to speak for themselves. |

Systematic integrative review using narrative and meta-analysis. Rigor: Strong (comprehensive search, assessment of study quality, rigorous meta-analysis/synthesis). | Fifty-five papers were included in the review. Seven interventions were tested; all were narrowly focused, and none was evaluated by comparing wishes for end-of-life care with care received. One intervention demonstrated effects on patient/family outcomes in the form of improved wellbeing and anxiety following sessions with a peer mentor. Qualitative studies showed the importance of instilling patient confidence that their advance directives will be enacted and discussing decisions about (dis)continuing dialysis separately from “aggressive” life-sustaining treatments (e.g., ventilation). Of eight intervention studies identified, four were RCTs, two used a predesign/postdesign, and two reported postdata without comparison. Rating of bias identified six of these studies as poor quality and two as fair. |

Loss of cognitive capacity is common, leaving families and nephrologists to decide whether to withdraw dialysis, so that patients may continue on dialysis or be resuscitated or ventilated, when they would have chosen otherwise. ACP facilitates an opportunity for discussion of treatment preferences, ensuring health care providers and family members are aware of patients' wishes. | Interventions do not give comprehensive attention to patient, caregiver, health professional, and system-related factors. Implementation enhanced by educating staff on the benefits of early ACP and ensuring staff have time for ACP as “core business.” Patients tended to wait for health professionals to raise ACP and dramatically overestimated their life expectancy; nephrologists discussed EOL issues based on prognosis but struggled to identify a suitable juncture; nurses felt uncomfortable raising ACP for fear of upsetting patients, families, and senior staff; judging the optimal timing for the ACP was difficult. Surrogates are influenced by their ideas rather than patient preferences, leading to poor congruence concerning EOL care decisions such as discontinuation of dialysis. |

| Noble (2008), UK. Review questions: 1) What are the experiences of those opting not to have dialysis to treat renal disease and their carers? 2) What is the difference in experience and trajectory to death, for those withdrawing from dialysis compared with those choosing not to start dialysis? |

Systematic review: Studies were included if they had been peer-reviewed and included adult populations with a principal diagnosis of ESRD. No specific intervention but advance care planning was included. |

Systematic narrative review: Papers were themed. Rigor: Weak (quality of studies not assessed; analysis is not clearly reported). |

Fifty-one quantitative papers and three qualitative papers included in the review. The presence of an advance directive requesting the cessation of dialysis, in addition to the family preference to stop dialysis, led to most nephrologists saying that they would stop dialysis. American nephrologists were more likely to stop than German or Japanese nephrologists. If the family disagreed with the patient's advance directive, nephrologists were less willing to stop dialysis. |

Patients identified hope as central to the advance care planning process in that hope helped them to identify future goals of care and influenced their willingness to engage in end-of-life discussions. | Potential barriers to hope were a reliance on health care professionals to initiate end-of-life discussions and the need for staff to focus on their daily clinical work. |

| Randomized controlled trials | |||||

| Briggs (2004), USA Objectives: To examine feasibility of patient-centered advance care planning (PC-ACP) and reliability of data collection instruments. |

Patients aged 50 yrs or more (and surrogates) attending heart failure, renal dialysis, and cardiovascular surgery clinics. Intervention: One-hour PC-ACP interview, delivered by an experienced ACP facilitator; focused on patient understanding/misconceptions of condition and ACP; what the patient would want the chosen surrogate to understand and act on; summary of choices and need for future discussions. |

Pilot RCT: patient/surrogate pairs. Randomized to PC-ACP (n = 13) or “usual care” (n = 14)—written material on advance directives, with referrals to trained advance care planning facilitators if requested. Predialysis patients offered a class on dialysis treatment choices and consequences. Rigor: Weak (Randomization not concealed. Gender and surrogate (spouse/child) imbalance in the groups. Small sample size). |

The experimental group had superior outcomes in congruence in statement of treatment preferences, decisional conflict, and patient's perceived quality of communication; but not in surrogate's perceived quality of communication, patient knowledge of ACP, or surrogate knowledge of ACP. | Deeply involving the surrogate as the patient clarifies their values and preferences will enable them to better represent the patient. | Interviewer skilled in facilitating difficult conversations regarding future medical care. |

| Kirchhoff (2012); USA Objectives: 1) to identify patient choices using patient-centered advance care planning (PC-ACP) compared with usual care, and 2) for those patients who died, to assess whether their EOL care was in accord with their choices stated on study intake. |

Patients (and their surrogates) with a diagnosis of end-stage congestive heart failure (CHF) or ESRD; at risk of serious complication or death in the next two years; receiving outpatient medical care, from two centers in Wisconsin. Intervention: 1–1.5 hour PC-ACP interview, delivered by a trained ACP facilitator to assess the patient and surrogate understanding of illness; provide information about treatment options and their benefits and burden; assist in documentation of treatment preferences; help prepare surrogates to make decisions that honor the patient's preferences; ending with the documentation of patient preferences for care using the Statement of Treatment Preferences form. |

RCT: 313 patients with CHF (n = 179) or ESRD (n = 134) and their surrogates who were randomized to receive either PC-ACP (n = 160; CHF = 88, r = 70) or usual care (n = 153; CHF = 89, r = 64). Rigor: Moderate (clear objectives, adequate randomization, not blinded, good follow-up, underpowered). |

Among ESKD patients, significantly more experimental patients (37.7%) chose to withdraw from dialysis than controls (17%)—however, this was not discussed in the interview. Hundred and ten deaths; 74% (n = 81) of the patients made their own decisions until death and therefore received care in accord with their wishes. Patients and surrogates were usually appreciative of discussions. They asked why no one had raised these issues earlier. |

When we are doing disease-specific planning, we are really helping prepare both the surrogate and the patient to face future decisions in a more informed and prepared way. | The facilitators (selected nurses, social workers, and chaplains) were trained in delivery of the intervention and observed during the study. They received video-taping, evaluation, and feedback. Health professionals reluctant to hold sensitive discussions. Routinizing the discussions requires a facilitator and dedicated time, checking to see if preferences have changed. |

| Perry (2005); USA Objectives: To explore the impact of peer mentors (dialysis patients trained to help other patients) on end-of-life planning. |

Patients from 21 dialysis centers across Michigan. Intervention: Peers were trained through an advance directive (AD) workshop and also completed their own ADs. Eight contacts with patients over a two- to four-month period: three face-to-face and five by phone. Discussion of chronic illness experiences, values, spirituality, fears, AD issues, and documents. |

RCT: 203 participants in three groups: usual care (n = 81); printed material on AD (n = 59); peer intervention (n = 63). Rigor: Moderate (randomization briefly described; nonblinded outcome assessment). |

Peer mentoring significantly increased the completion of ADs overall; most prominently among African Americans, also improving comfort discussing subjective wellbeing and anxiety. Among white patients, printed material on ADs decreased reported suicidal ideation. | Face-to-face relationship with someone with similar experiences engenders trust, which motivates completion of ADs. | African Americans may be more open to peer interventions because their culture partakes of oral, rather than written traditions, which may be mistrusted. |

| Song (2010), USA Objectives: To determine the feasibility and acceptability of patient-centered advance care planning (PC-ACP) among African Americans and their surrogate decision-makers. |

African Americans over 18 with stage 5 CKD receiving either center hemodialysis or home peritoneal dialysis for at least three months and their surrogates. Intervention: One-hour PC-ACP interview, delivered by a trained ACP facilitator. Addressing: 1) representational assessment of participants' beliefs about their illness; 2) exploration of misunderstandings about CKD and life-sustaining treatment, including dialysis; 3) creation of conditions for conceptual change; 4) introduction of replacement information; and 5) summarization of the discussion. |

Pilot RCT: 19 patient/surrogate pairs. Randomized to PC-ACP (n = 11) or “usual care” (n = 8)—written information on advance directives provided by a nurse or social worker who encouraged patients to complete an AD and addressed their questions about life-sustaining treatment options. Questions about medical options were referred to physicians. Rigor: Moderate (clearly focused question, randomization acceptable, outcome data collectors blinded, very small sample size). |

Significantly greater congruence and quality of communication in the intervention dyads. No significant difference in patient-clinician interaction, patient's difficulty in making choices, surrogate's comfort in decision-making, or psychospiritual wellbeing of the patient and surrogate. A shift among participants toward using all possible life-sustaining treatments to prolong their lives. |

PC-ACP promotes skills related to initiating discussions, assisting individuals in the identification of values and goals related to their health care, and developing educational and organizational systems that are effective in implementing an individual's plan of care. | African Americans typically prefer continuing life-sustaining treatment. |

| Song (2015); USA Objectives: To test the effect of an ACP intervention on preparation for EOL decision-making for dialysis patients and surrogates, and for surrogates' bereavement outcomes. |

Patients dialyzed for at least six months and at risk of dying in the next 12 months, and their surrogates, from 20 dialysis centers in North Carolina. Intervention: A psychoeducational intervention to help patients clarify EOL preferences and prepare the surrogate for making decisions on the patient's behalf, with a trained nurse facilitator at the center and a follow-up session at home two weeks later, with completion of a “goals of care” document to indicate patient preferences and ADs. Facilitator adherence to protocol monitored. |

RCT: 210 dyads randomized to intervention (n = 109) and control (n = 101) groups. Rigor: Strong (concealed randomization, blinded outcome assessment, sample size adequate, although small for bereavement measures). |

Dyad congruence and surrogate decision-making confidence were better in the intervention group, but patient decisional conflict did not differ between groups. Forty-five patients died during the study. Intervention surrogates had less anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic distress than controls. |

ACP can help prepare patients and surrogates for treatment decision-making at the end of life by providing individualized information on effectiveness of mechanical supports at the end of life; by helping the patient to clarify values; and by actively involving the surrogate to help prepare for the emotional burden of decision-making. | Intervention sessions were audited for fidelity and refresher training offered. African Americans have been reported as less amenable to ACP, but the focus on decision-making rather than advance directives could have made this more acceptable. |

| Song (2016)*; USA Objectives: To compare the efficacy of an ACP intervention on preparation for end-of-life decision-making and postbereavement outcomes for African Americans and whites on dialysis. *A secondary analysis of data from Song (2015) |

Patients dialyzed for at least six months and at risk of dying in the next 12 months, and their surrogates, from 20 dialysis centers in North Carolina. Intervention: a psychoeducational intervention to help patients clarify EOL preferences and prepare the surrogate for making decisions on the patient's behalf, with a trained nurse facilitator at the center and a follow-up session at home two weeks later, with completion of a “goals of care” document to indicate patient preferences and ADs. Facilitator adherence to protocol monitored. |

A secondary analysis of data from a randomized trial comparing an ACP intervention (Sharing Patient's Illness Representations to Increase Trust [SPIRIT]) with usual care was conducted. There were 420 participants and 210 patient-surrogate dyads (67.4% African Americans). Rigor: Moderate (the study was not powered to test the interaction of the intervention with race). |

Among African Americans (but not whites), the intervention was superior to usual care in improving dyad congruence and surrogate decision-making confidence two months after intervention and in reducing surrogates' bereavement depressive symptoms. | ACP can help prepare patients and surrogates for treatment decision-making at the end of life by providing individualized information on effectiveness of mechanical supports at the end of life, by helping the patient to clarify values, and by actively involving the surrogate to help prepare for the emotional burden of decision-making. | It may be that the intervention aligns with African Americans' familial, religious, and communal frame of reference; whites in the control group seemed to benefit simply from being asked thought-provoking questions repeatedly. |

| Non-RCT intervention studies | |||||

| Eneanya (2015), USA Objectives: To test the shared decision-making renal supportive care communication intervention to systematically elicit patient and caretaker preferences for end-of-life care so that care concordant with patients' goals can be provided. |

Hemodialysis patients who are at high risk of death in the ensuing six months, attending 16 dialysis units associated with two large academic centers. Intervention: Nephrologists and social workers will communicate prognosis and provide EOL planning in face-to-face encounters with patients and families using a social work–centered algorithm. Follow-up sessions with the social worker will take place monthly to provide further support, education, information, and referral to resources such as hospice. |

Protocol for a prospective cohort study with a retrospective cohort serving as the comparison group. | Protocol: No results | The intervention systematically elicits patient preferences for EOL care, so that concordant care can be provided. | |

| Hayek (2014), USA. Objectives: To examine the effectiveness of an electronic medical record (EMR)-based reminder in improving AD documentation rates. |

Hundred and fifty-seven patients aged >65 yrs, CHF, COPD, AIDS, malignancy, cirrhosis, ESRD, or stroke attending a hospital outpatient clinic. Intervention: Adding a visual reminder of “Advanced Directives Counseling” to the EMR problem list of outpatients with high risk for morbidity/mortality. |

Design: Test-retest of nonequivalent groups—initial cross-sectional estimation of the percentage of patients with documented ADs; retested twice over the following year. Rigor: Weak (design open to confounding, fair sample size. Lack of detail on physicians' AD discussions with patients). |

Of the initial pre-intervention sample (n=100) none had AD documented. 588 patients were screened and 157 (26.7%) were eligible. Over 6 months, 64 of these patients were seen in clinic; 38 had AD on their problem list. By the end of the study, 29 (76%) charts with the EMR reminder had documentation of an AD, compared to 3 (11.5%) of those without. Results suggest that EMR reminders may improve AD documentation rates. | By adding AD to the patient's active problem list, its importance is highlighted and seen as equivalent as the patient's medical problems, therefore encouraging physicians to address them. | E-mail and visual alerts contribute to information overload, leading physicians often to either ignore or avoid them. The intervention in the present study was simple, cost-effective and did not require any extra financial or human resources. Combining AD discussions with the outpatient visit workflow serves as a reminder to the health care provider. |

| Seal (2007), Australia Objectives: To explain the role of patient advocacy in the advance care planning process. |

Nurses on the palliative care, respiratory, renal and colorectal pilot wards, and the hem-oncology coronary care, cardiology, and neurology/geriatric control wards. Intervention: The Respecting Patient Choices Program (RPCP) to improve use of AD through a framework of educative, patient information, safety and quality systems, and policy support for ACP, plus equipping mainly nurses, through a comprehensive two day training course, with skills and resources to facilitate the process. |

A prospective nonrandomized controlled trial, with focus groups. 74 in the intervention group; 69 in the control group. Rigor: Weak (nonvalidated questionnaires; nonrandomized trial with nonequivalent control group). |

Statistically significant differences in favor of the intervention wards in nurses' self-reported willingness, efficacy, and job satisfaction in relation to upholding patients informed choices about their end-of-life treatment, supported by focus group findings. | Being able to provide information to patients while they were still well enough to talk with their families stimulated communication, enabling people to determine their future care and easing their concerns about loss of control. The program provided a legitimate platform for nurses to empower patients and to advocate on their behalf. | Organizational endorsement of ACP with framework of RPCP encouraged nurses to be patient advocates. Pressure from medical staff and relatives to treat at all costs can prevent the patients' wishes being respected. |

| Weisbord (2003), USA. Objectives: To identify symptom burden, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and advance directives in extremely ill hemodialysis patients to assess their suitability for palliative care and to ascertain the acceptability of palliative care to patients and specialist health professionals. |

Nineteen patients who received outpatient dialysis three times per week in a hospital, for at least three months, and had modified Charlson comorbidity scores of P8. | Single-group test-retest study. Each patient completed surveys to assess symptom burden, HRQoL, and prior advance care planning. Palliative care specialists then visited patients twice and generated recommendations. Patients again completed the surveys, and dialysis charts were reviewed to assess nephrologists' compliance with recommendations and nephrologists' documentation of symptoms reported by patients on the symptom assessment survey. Rigor: Weak (small, single-group test-retest study). |

Patients: mean age 67 yrs, majority male, six of the 19 patients died before end of the study. Advance care planning: Twelve patients (63%) had never spoken to their nephrologist about their wishes for care at the end of life; five (26%) had never spoken to their family or friends. Six (32%) had executed a living will, and of these, four had informed their nephrologist verbally and three had presented a copy of the document to their nephrologist. Seventeen patients (89%) reported having someone they desired to make medical decisions for them at the end of life; six (32%) had formally appointed this person in writing as a surrogate decision-maker. Postintervention assessment: no differences were observed in symptoms, HRQoL, or number of patients making advance directives as a result of the intervention. |

Patients have significant symptom burden and impaired HRQoL. Only a small number officially documented their wishes for their future care. | Nephrologists did not implement recommendations related to addressing advance directives or to pursuing workup for ongoing medical problems. Patients may discuss these issues with nurses, dieticians, and social workers, so incorporating palliative care may depend on their input. |

| First Author, Country, and Objectives | Population and Setting | Design, Methods of Data Collection, and Methodological Rigor (Strong/Moderate/Weak) | Key Results | Explanation of the Results | Contextual Features Thought to Influence Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | |||||

| Al-Jahdali (2009), Saudi Arabia. Objectives: To examine the preferences for CPR and end of life medical intervention among Saudi HD patients. |

Hundred patients from two hospitals hemodialyzed for two yrs or more (mean duration 6.0 years). | Multicenter cross-sectional, observational study. Data collection: questionnaire completed during dialysis capturing demographics, education, employment, family size, knowledge of CPR, mechanical ventilation, and ICU admission; and responses to scenarios on EOL decisions, medical interventions, CPR, ICU admission, and surrogate decision-makers. Rigor: Moderate (questionnaire trialed on a sample of patients, appropriate use of statistics to interpret data). |

More than 95% of patients had little or no knowledge about CPR, intubation, and mechanical ventilation; majority wanted their physician to make decisions about CPR if they did not have an AD, and only 22% believed that decisions should be made by family members. Overall, physicians should advise patients about their disease/prognosis and discuss the effects of future medical interventions. Informed patients can make rational choices about EOL issues. | Limited patient education about CPR and ventilatory support. ACP preferences are rarely discussed with patients and their families. Physicians may lack time, training, or be uncomfortable with EOL discussions. |

In Saudi society, ADs are not routinely discussed (not for religious reasons but) because physicians fear distressing patients. |

| Anderson (2006), USA. Objectives: To establish the preferences and directives of severely ill dialysis patients/surrogates and whether these change with time or are influenced by patient's functional status; and whether ACPs established by patients correlate with clinical outcomes. |

Hundred and nine peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients in an academic nursing home. | Design: Retrospective chart review of PD patients. Patients were followed up to death or loss to follow-up during a 14-year period (1986 to 2000). Rigor: Strong (all data extracted systematically and appropriate use of statistics). |

60.6% of patients were women, 54.1% were white, 45.0% African American, and 0.9% Asian. ACPs were obtained for 108 patients. Do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) status was significantly associated with increased age, lower ADL scores, coronary disease, amputation, and dementia. In compliance with ACP: patients indicating do not hospitalize (DNH) spent as much time in hospital as those planning to accept hospitalization. Seven of 46 patients designated attempt CPR (ACPR) had CPR attempted. For these chronically ill patients, age and functional status strongly influence DNAR and DNH plans. ACP was not conclusive in determining events during acute illness. |

Nonadherence with DNH and ACPR plans may have occurred due to decisions about hospitalization during times of acute illness with patients who retained capacity (or their surrogates) who changed their minds. CPR not being attempted for ACPR patients may be because CPR is rarely performed in nursing homes. | The near-complete participation with ACP is attributable to the facility's explicit requirement for ACP, the commitment of staff in ACP participation, and high rates of face-to-face discussions with patients and family. African American patients participated in ACP as often as whites due to discussions and inclusion of family members. |

| Calvin (2006), USA. Objectives: To develop an instrument to assess readiness of patients with chronic kidney disease to discuss advance care plans. |

Questionnaire assessed for content validity by a panel of four experts in end-of-life care, and a patient panel of five persons currently being treated with HD in an inpatient setting. Thirty-item instrument piloted with another sample of 10 patients on HD. | Design: Development of a questionnaire. Rigor: Weak (content validity and reliability assessed in the instrument but only using a small sample. Inadequate reporting of results from the pilot questionnaire). |

Content validity—Most patients rated the items as very relevant and very clear, but the professional panel ratings were more varied. Reliability—Cronbach's alpha (0.88) for the 30-item questionnaire. Patients also reported the item was “helpful and not difficult” and “gave me something to think about.” |

The questionnaire has the potential to ease the initiation of ACP discussions for health care providers—AD completion may remain low among patients with kidney failure because health care professionals are not assessing patient readiness to discuss ACP. | |

| Collins (2013), Ireland. Objectives: To investigate the views of HD patients on death and dying; beliefs about what is worse than death; likelihood of talking about death and dying and issues related to end-of-life care and ACP. |

Fifty HD (minimum three months) adult patients attending a hospital dialysis unit. | Design: Cross-sectional, questionnaire (modified version of the EOL survey developed by Life's End Institute) survey with a convenience sample of all adult patients. Rigor: Moderate (clear objectives, adequately sized convenience sample). |

Most participants were comfortable discussing death, but not always among family, with most wanting medical interventions to extend life. The control of pain and other symptoms, being physically comfortable and being at peace spiritually were the most important issues at end of life. | Generally, dialysis patients believed that their chances of survival were as good as anyone else's and did not see themselves as having a terminal illness, so issues relating to death and dying were rarely considered. The majority wanted medical intervention to extend life. | ADs have no legal status in Ireland, and very few people are aware of their existence. Health care professionals developed good relationships with patients allowing the discussion of sensitive topics and providing accurate information supported informed decisions. |

| Davison (2010), Canada. Objectives: To evaluate EOL care preferences of CKD patients, highlight gaps between current EOL care practice and patients' preferences, and to help prioritize and direct future innovation in EOL care policy. |

Hundred CKD patients (stages 4 and 5) in dialysis, transplantation, or predialysis clinics in a university-based renal program. | Design: Survey development and implementation (n = 584). Survey developed from literature review aiming to identify patients' preferences and expectations of EOL care, such as place of death, symptom treatment, and advance care planning. Preferences for hypothetical clinical EOL scenarios were also included. Rigor: Strong (survey rigorously reviewed by experts and piloted in four dialysis units; large sample). |

Patients relied on decision-making by the nephrology staff for EOL care; pain and symptom management, ACP, and psychosocial and spiritual support. ACP: Patients were comfortable discussing EOL issues with family and nephrology staff, yet less than 10% had done so, and only 38.2% had completed an advance directive Patients had poor knowledge of palliative care options and of their illness trajectory; 84.6% felt well informed but only 17.9% felt that their health would deteriorate over the next year. 61% regretted their decision to start dialysis. EOL care that patients most wanted was better education and support for staff, patients, and families, greater involvement of family, more focus on pain and symptom management, what to expect clinically near the end of life, palliative care, and hospice services. |

CKD patients need to be better informed with EOL care issues; symptom management was a significant priority for patients but pain in CKD is both underrecognized and undertreated. Current EOL clinical practices do not meet the needs of patients with advanced CKD. |

Doctors and nurses are vital for providing emotional, social, and spiritual support. However, a focus on technology has drawn physicians away, leaving emotional and spiritual support mainly to nursing staff and other professionals such as social workers and spiritual counselors. |

| Feely (2016), USA. Objectives: To retrospectively examine the prevalence and contents of ADs used by HD patients. |

Review of medical records of all HD patients (n = 808) in an academic medical center. | Design: Retrospective review of medical records of all HD patients over a five-year period (2007–2012). Data collected: Demographics, prevalence of ADs, and content analysis of those ADs with emphasis on management of EOL interventions including dialysis. Rigor: Strong (large sample size, clear objectives, and results well described and discussed). |

Forty-nine percent had ADs; 10.6% mentioned dialysis; and 3% specifically addressed dialysis management at EOL. Patients who had ADs were older. For HD patients who had ADs, more addressed CPR, mechanical ventilation, artificial nutrition and hydration, and pain management than dialysis. | Patients may have had ADs because they are more aware of their reduced life span and are encouraged by health professionals, especially, when they have comorbidities and see a range of professionals. | Patients receiving in-center HD come into contact with several health care professionals and create multiple opportunities for this high-risk group to complete ACP. |

| Janssen (2013), The Netherlands Objectives: To investigate HD patient preferences for life-sustaining treatments; and to examine the quality of patient-physician communication about EOL care, including barriers and facilitators to this communication. |

Eighty ESRD HD patients attending dialysis departments in six hospitals. | Design: Cross-sectional, observational study examined palliative care needs using a convenience sample of ESRD patients. Validated questionnaires, administered at home or during dialysis sessions, to measure comorbidity, quality of life, willingness to accept life-sustaining treatment, and quality of/barriers to communication. Nephrologists completed a questionnaire on ACP for each patient to evaluate if they discussed prognosis of survival, preferences for CPR and mechanical ventilation, the EOL, and palliative care with the patient. Rigor: Moderate (small convenience sample but validated questionnaires used). |

All patients communicated their choices for life-sustaining treatments and place of death. Thirty percent of patients discussed life-sustaining treatments with their nephrologist, and quality of patient-physician communication about EOL care was rated poor. Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication were identified, e.g., barrier's “I would rather concentrate on staying alive than talk about death”; and facilitators “my doctor cares about me as a person.” | Sixty-five percent of patients reported that they were not ready to talk about the care they want if they get very sick, making it unlikely that they would initiate ACP discussions. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care is poor: prognosis, dying, and spirituality are infrequently discussed. Most patients stated that they wanted CPR but are likely not aware of low success rates with CPR. |

In this setting, continuity of care was lacking and patients did not know which doctor was going to be caring for them at the EOL, which hindered development of ACP. |

| Rodriguez Jornet (2007), Spain. Objectives: To investigate dialysis patients' wishes for health care if their condition became untreatable; and to provide patients the opportunity to create an AD. |

Hundred and thirty-five dialysis patients (aged 18–95 yrs) on dialysis for more than three months and not expected to die within three months. | Design: Questionnaire gathering data on demographics, medical status, and preference for interventions in the event of deterioration. Rigor: Weak (statistics not a good fit for the design and no details regarding validation of the questionnaire). |