Description

A 75-year-old woman presented with a 3-week history of escalating nocturnal neuropathic pain affecting her left thigh. This pain was described as sharp and ‘shooting’ in nature, primarily in the upper outer part of her thigh, with a severity of ‘10/10’ at its worst. She had a medical history of osteoarthritis, hypercholesterolaemia, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, a complete left bundle branch block with normal cardiac function and intestinal metaplasia for which she was undergoing regular endoscopic surveillance. She provided a strong family history of malignancy, with colorectal cancer in her sister, ovarian cancer in her mother, oesophageal cancer in her father, and lung and prostate cancer in her brother. Of note, in this time she had not experienced any trauma, fevers, fatigue, altered bowel habits, or weight loss.

The clinical exam revealed loss of the ankle reflex on the left side despite reinforcement but no other discernible neurological deficit. The musculoskeletal exam was unremarkable.

Given her strong family history of malignancy, the clinical team pursued a workup to rule out a paraneoplastic neuropathy from an undiagnosed primary malignancy. The patient underwent CT imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and tumour markers were performed including carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein, cancer antigen 19–9, cancer antigen 125 and calcitonin. Additionally, she was counselled for DNA mismatch repair testing to exclude Lynch syndrome. These aforementioned tests returned negative, rendering the possibility of malignancy or a systemic process unlikely.

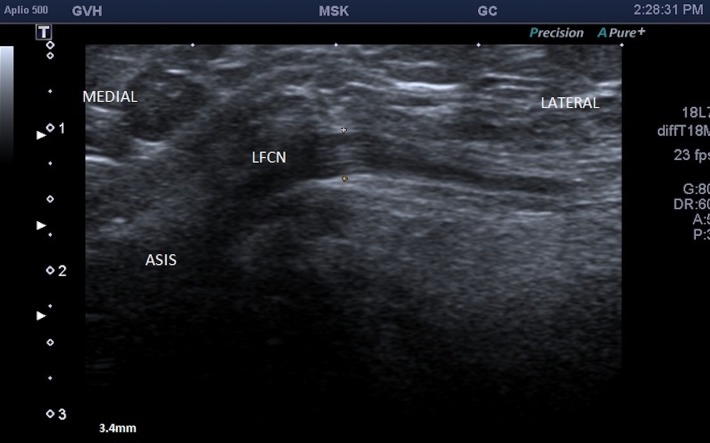

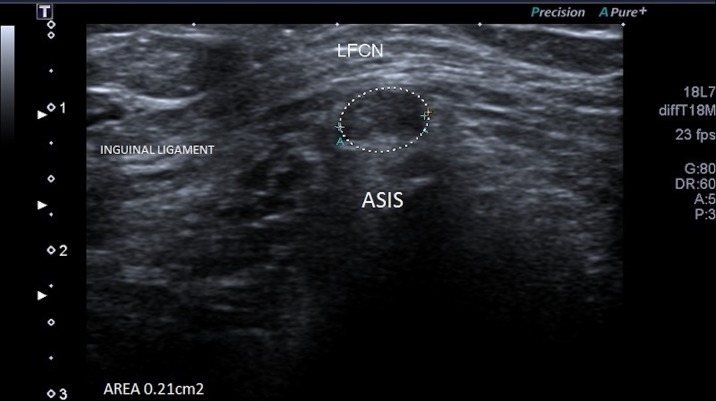

Eight weeks following initial presentation, a focal ultrasound of the groin and left thigh was performed which revealed a thickened and abnormally hypoechoic left lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, measuring 3.4 mm in diameter (figures 1 and 2) compared with 2.2 mm on the right side (figure 3). There was loss of the normal fascicular pattern between the anterior superior iliac spine and the inguinal ligament, consistent with nerve entrapment. At this point, the diagnosis of left meralgia paraesthetica was made.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image demonstrating a thickened and abnormally hypoechoic left lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN).

Figure 2.

Axial view of the left lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN).

Figure 3.

Normal right lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) measuring 2.2 mm.

She was treated with a corticosteroid injection to the left inguinal ligament adjacent to the neurovascular bundle, with subsequent resolution of symptoms.

Meralgia paraesthetica describes anterolateral thigh pain and/or dysaesthesia caused by compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.1 Though primarily diagnosed based on clinical assessment, this case demonstrates the utility of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool when the presentation remains undifferentiated. In a high-risk patient, it is worthwhile considering malignancy with local effect2 or an associated paraneoplastic phenomenon3 as the cause of systemic or focal symptoms distant from the tumour site.

Learning points.

Investigations have previously been perceived to be of limited utility in the diagnosis of meralgia parasthetica, with nerve conduction testing producing variable results. The presented case demonstrates the benefit of ultrasound as an imaging modality in the diagnosis of meralgia paraesthetica through demonstration of a thickened and hypoechoic femoral cutaneous nerve.

As a general principle, when contemplating a list of differential diagnoses, investigations should begin with the highest-yield modalities, bearing in mind the likelihood of the condition and the cost effectiveness of the relevant test.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals: Mr A Goh for his assistance with technical support and proofreading. Mr G Curley (Ultrasound Supervisor, Goulburn Valley Health) for his assistance with the selection and acquisition of the ultrasound images.

Footnotes

Contributors: AE contributed to conception of the submission by identifying this as a case with learning points. EN contributed to the planning, drafting and revising of the case report. PG contributed to annotation of the provided ultrasound images.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Dr AE, a listed author for his contribution to conception of this case study, has a personal relationship with the patient deidentified in the case report. He was not, however, involved in her medical care or treatment decisions. In retrospect after her recovery, he identified the learning points of this case and made recommendation for the medical records of the patient to be reviewed by an objective third party.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ivins GK. Meralgia paresthetica, the elusive diagnosis: clinical experience with 14 adult patients. Ann Surg 2000;232:281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tharion G, Bhattacharji S. Malignant secondary deposit in the iliac crest masquerading as meralgia paresthetica. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:1010–1. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90067-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koike H, Sobue G. Paraneoplastic neuropathy. Handb Clin Neurol 2013;115:713–26. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52902-2.00041-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]