Abstract

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a rare disease characterised by venous and/or arterial thrombosis, pregnancy complications and the presence of specific autoantibodies called antiphospholipid antibodies. This review aims to identify existing clinical practice guidelines (CPG) as part of the ERN ReCONNET project, aimed at evaluating existing CPGs or recommendations in rare and complex diseases. Seventeen papers providing important data were identified; however, the literature search highlighted the scarceness of reliable clinical data to develop CPGs. With no formal clinical guidelines in place, diagnosis and treatment of APS is largely based on consensus and expert opinion. Patients’ unmet need refers to the understanding of the disease and its clinical picture and implications, the need of education for patients, family members and healthcare providers, as well as to the development of monitoring pathways involving multiple healthcare providers.

Keywords: antiphospholipid syndrome, European reference networks, ERN ReCONNET, clinical practice guidelines, unmet needs

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Antiphospholipidsyndrome (APS) is a rare systemic autoimmune disease characterised by venousand/or arterial thrombosis, pregnancy complications and the presence ofspecific antiphospholipid autoantibodies.

Thereare still unmet needs with regard to diagnosis and management of APS.

What does this study add ?

This review identified all existing clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) on APS inorder to integrate possible recommendations.

How might this impact on clinical practice or futuredevelopments?

Theliterature search highlighted the scarceness of reliable clinical data todevelop CPGs.

Diagnosisand treatment of APS is largely based on consensus and expert opinion.

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a systemic autoimmune disease with the highest prevalence in women of childbearing age, characterised by venous and/or arterial thrombosis, pregnancy complications and the presence of specific autoantibodies called antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies. APS is a rare disease; although accurate figures for incidence and prevalence are lacking, it is generally considered to fall within the Orphanet definition of rare disease, being a disease not affecting more than 1 person per 2000 (https://www.orpha.net/consor4.01/www/cgi-bin/Disease.php?lng=EN). Due to its low prevalence, not many randomised, controlled clinical trials have been undertaken. This review aims to identify all existing clinical guidelines on APS, to integrate possible recommendations and to identify unmet needs with regard to diagnosis and management of APS. This work has been driven by the ERN ReCONNET team that performed the literature research and assisted the authors during the whole search process. In addition, ERN ReCONNET allowed for the first time, at least to our knowledge, to write a manuscript including both patients and physicians’ opinions about the disease and its management.

Methods

We carried out a systematic search in PubMed and Embase based on controlled terms (MeSH and Emtree) and keywords of the disease and publication type (clinical practice guidelines (CPG)). We reviewed all the published articles in order to identify existing CPGs on diagnosis, monitoring and treatment, according to the Institute of Medicine 2011 definition (CPGs are statements that include recommendations intended to optimise patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options).

The disease coordinator of the ERN ReCONNET for APS has assigned the work on CPGs to the healthcare providers (HCP) involved. This publication was funded by the European Union’s Health Programme (2014-2020), Framework Partnership Agreement number: 739531 – ERN ReCONNET. The content of this publication represents the views of the authors only and it is their sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Moreover, in order to implement the list of guidelines provided by Medline and Embase search, the group also performed a hand search. A first screening among papers included in the final list (systematic search +hand search) was based on title and abstract selected evidence-based medicine guidelines. A general assessment of the CPGs was performed following the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation II tool checklist1 not used for formal appraisal but rather intended to inform discussion. A discussion group was set for the evaluation of the existing CPGs and to identify the unmet needs.

Shown below are the terms used in the search strategy:

Medline (PubMed): (“antiphospholipid syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“antiphospholipid”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “antiphospholipid syndrome”[All Fields]) AND (“Practice Guideline”[Publication Type] OR “Practice Guidelines As Topic”[MeSH Terms] OR Practice Guideline[Publication Type] OR “Practice Guideline”[Text Word] OR “Practice Guidelines”[Text Word] OR “Guideline”[Publication Type] OR “Guidelines As Topic”[MeSH Terms] OR Guideline[Publication Type] OR “Guideline”[Text Word] OR “Guidelines”[Text Word] OR “Consensus Development Conference”[Publication Type] OR “Consensus Development Conferences As Topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “Consensus”[MeSH Terms] OR “Consensus”[Text Word] OR “Recommendation”[Text Word] OR “Recommendations”[Text Word] OR “Best Practice”[Text Word] OR “Best Practices”[Text Word]). Embase: ('antiphospholipid syndrome'/exp OR 'Hughes syndrome' OR 'antiphospholipid syndrome' OR 'primary antiphospholipid syndrome' OR 'syndrome, antiphospholipid') AND ('practice guideline'/exp OR ‘practice guideline’ OR ‘practice guidelines’/exp OR ‘practice guidelines’ OR 'clinical practice guideline'/exp OR ‘clinical practice guideline’ OR ‘clinical practice guidelines’/exp OR ‘clinical practice guidelines’ OR 'clinical practice guidelines as topic'/exp OR ‘clinical practice guidelines as topic’ OR ‘guideline'/exp OR ‘guideline’ OR ‘guidelines’/exp OR ‘guidelines’ OR 'guidelines as topic'/exp OR ‘guidelines as topic’ OR ‘consensus development’/exp OR ‘consensus development’ OR ‘consensus development conference’/exp OR ‘consensus development conference’ OR ‘consensus development conferences’/exp OR ‘consensus development conferences’ OR ‘consensus development conferences as topic’/exp OR ‘consensus development conferences as topic’ OR ‘consensus’/exp OR ‘consensus’ OR ‘recommendation’ OR ‘recommendations’) AND [embase]/lim NOT [medline]/lim

State of the art on CPGs

By a systematic search, 808 papers were identified initially; 25 papers were added by hand search. A total of 439 papers were selected and screened on full text. Out of these, a total of 18 papers2–19 were finally evaluated. Among these 18 papers, one paper was excluded from the evaluation because this was a report of a task force meeting, reflecting expert opinion.17

At this moment, no formal CPGs covering all the aspects of diagnosis and treatment of APS could be identified even if a conventional way to manage these patients, mainly experience based, has been identified. However, several papers were dealing with important issues and unmet needs, which should be included in a future guideline. The following paragraphs will summarise where we stand and what we still need to do.

Unmet needs

Clinicians’ unmet needs

We identified the following areas of uncertainty that need to be addressed in a guideline: laboratory tests and their standardisation,2–5 primary prophylaxis,6–10 thrombosis treatment,3 7–12 pregnancy and pregnancy-related issues management,3 7 13–16 non-criteria manifestations17 and catastrophic APS (CAPS).18 19

The articles that contain information about unmet needs are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

List of the references discussing unmet needs in APS

| Unmet needs | Articles |

| Laboratory tests | Bertolaccini et al,2 Keeling et al,3 Lakos et al,4 Pengo et al 5 |

| Primary prophylaxis | Alarcon-Segovia et al,6 Bertsias et al,7 Bertsias et al,8 Groot et al,9* Ruiz-Irastorza et al 10 |

| Thrombosis treatment | Bertsias et al,7 Bertsias et al,8 Ruiz-Irastorza et al,10 Crowther and Wisloff,11 Keeling et al, 3 Meroni et al,12 Groot et al 9 |

| Obstetric complications | Keeling et al,3 Bates et al,13 de Jesus et al,14 Huchon et al,15 Andreoli et al,16 Bertsias et al 7 |

| Non-criteria manifestations | Abreu et al 17 (note: negatively graded through AGREE-II tool, no original data but expert opinion) |

| Catastrophic APS | Asherson et al,18 Groot et al 9* |

*Paediatric articles.

AGREE, Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome.

Laboratory tests

Although standardised testing for lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin and anti-beta2GPI antibodies remains a concern, both influencing research and clinical diagnosis, clear recommendations on best practices for immunoassays for the measurement of aPL (by the three tests) and on the most important requirements for technical and performance characteristics have been published.3 4 Today, the complete antibody profile is required for diagnosis and classification of patients with APS, and most importantly for the risk assessment of both pregnancy morbidity and thrombosis. In fact, patients with the so-called ‘triple antibody positivity’, those with LAC test positivity or those with high IgG aCL/anti-beta2GPI titres are considered at higher risk. The clinical value of IgM aCL/anti-beta2GPI antibodies needs further studies. However, evidence that so-called ‘non-criteria’ aPL tests may contribute to the diagnosis and risk stratification in APS is building up. For instance, antibodies directed against domain 1 of beta2GPI were shown to correlate with triple positivity and correlate with higher titres of aPL.20 21 Furthermore, testing of ‘non-criteria’ antibodies such as antiphosphatidylserine and antiphosphatidylserine/prothrombin complex may be helpful in patients with clinical symptoms comparable with APS, but without positive classical antibodies, so-called seronegative APS. Including these non-criteria antibodies may result in a better identification of patients with APS.22 However, the clinical value of these antibodies remains to be proven.

Primary prophylaxis

Patients with positive aPL, but without clinical symptoms/events compatible with APS, presumably have a higher thrombotic risk profile, in particular patients who tested triple positive or have persistently high titres of aPL. How to prevent thrombotic events in this group of patients is still being debated. It is not clear if low-dose aspirin may or may not influence thrombotic risk,23 24 and the use of hydroxychloroquine for this purpose showed conflicting results.25 26 How to identify who to treat, and consequently how to treat, are still unanswered questions.

Thrombosis treatment

The mainstay of treatment of thrombotic APS remains vitamin K antagonists, although with recognised limitations especially in the long-term follow-up,27 failing to prevent recurrent events. Recommendations on treatment of a first thrombotic event, or a second event while on anticoagulation, both for venous and arterial thrombosis, have been published.28 However, these recommendations are largely based on expert opinion and randomised controlled clinical trials are mostly lacking. Although several reports suggest that additional drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine, rituximab, intravenous Ig and eculizumab, may have a place in the treatment of thrombotic APS, their position in clinical practice is not well defined.29–32 Direct acting oral anticoagulants for treatment of APS were investigated with special interest (mainly because of their administration that does not need international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring); these relatively new drugs are considered first-line therapy for atrial fibrillation and deep venous thrombosis in many countries. Unfortunately, at least for rivaroxaban, the efficacy and safety in patients with APS has not been demonstrated.33

In patients with APS, long-term anticoagulant treatment is indicated. Treatment withdrawal has been suggested for patients who became antibody negative.19

Obstetric complications

With the introduction of combined low-dose aspirin and low molecular weight heparin, most of the aPL-related pregnancy loss can be prevented.14

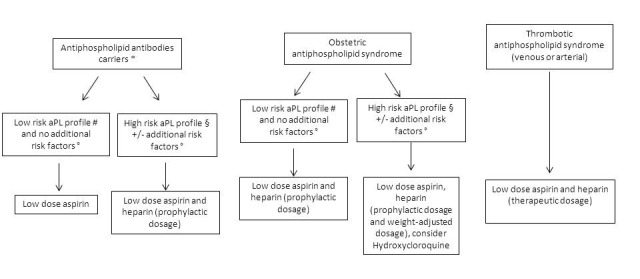

The ‘grading’ of treatment is linked to the clinical and serological disease profile (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conventional treatment to prevent obstetric complications during pregnancy. *Antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody carriers: individuals with aPL positivity without any anamnestic thrombotic event or pregnancy complications. #Low-risk aPL profile: single aPL positivity OR double positivity but low aPL titre OR IgM isotype. §High-risk aPL profile: triple aPL positivity OR LA positivity OR high-titre aCL and anti-B2GPI IgG/IgM. °Additional risk factors: risk factors for thrombosis other than aPL; autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Hydroxychloroquine can be added when indicated (ie, systemic lupus or autoimmunity features).

However, severe adverse pregnancy outcomes such as pre-eclampsia, low birth weight and early birth, and fetal deaths can still occur despite treatment.16 Additional treatments with hydroxychloroquine, low-dose prednisone and intravenous Ig have been suggested to be beneficial, but further studies are needed to confirm their clinical value.34–36 More experimental, pathophysiological-based approaches for the prevention of pregnancy loss and other pregnancy morbidity in APS are being investigated, including the use of statins.37

Based on experience, the use of combined contraceptive drugs in patients with APS is linked to an increased thrombosis risk and is therefore discouraged. Progestin pill is not always well tolerated by the patients. Therefore, intrauterine devices (with or without progestin) are actually recommended.16

Non-criteria manifestations

Though not part of the clinical classification criteria, symptoms and signs such as livedo reticularis, skin ulcers, sterile endocarditis, migraine, chorea, epilepsy and nephropathy are often observed in patients with APS. Treatment of these features is a matter of debate and based on expert opinion; no conclusive clinical studies on this subject have been performed; however, many experts suggest the use of old and new immunosuppressive treatments with or without low-dose aspirin and warfarin.19 38

Catastrophic APS

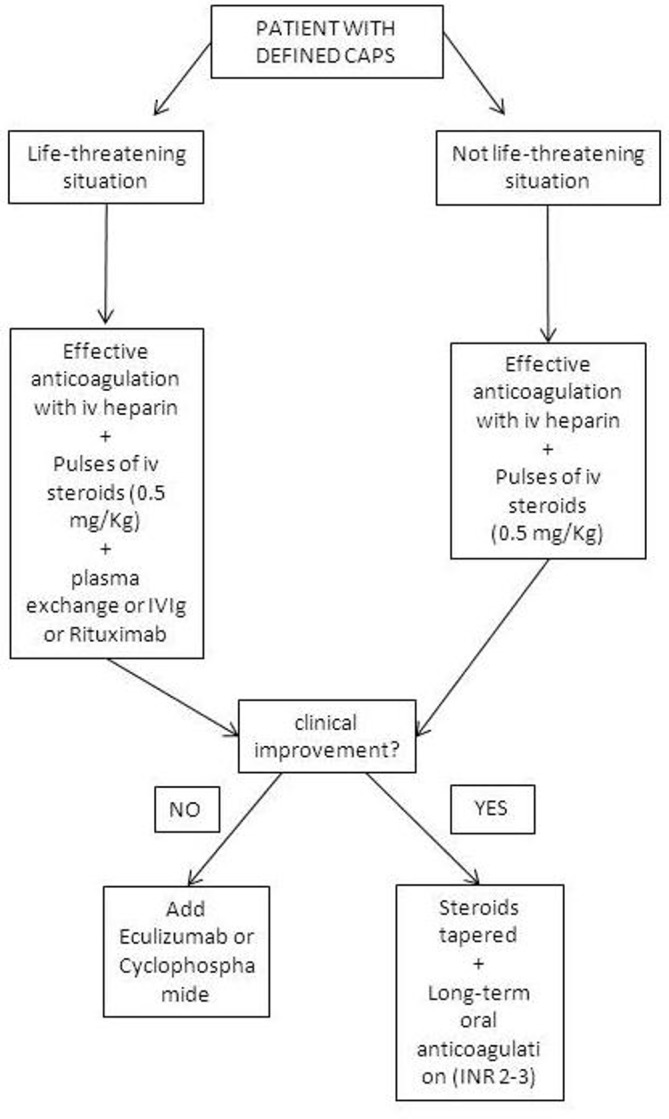

CAPS is a rare but very severe form of APS, characterised by multiorgan failure due to massive small vessel thrombosis, occurring in an estimated <1% of patients with APS. Data from the international CAPS registry show that treatment with a combination of heparin, corticosteroids, plasma exchange and/or intravenous Ig and, sometimes, rituximab or eculizumab, results in higher survival rates.39 A proposed algorithm of treatment is provided in figure 2. However, these data are based on a retrospective case series, subjected to inclusion bias. Due to the severity and rarety of the disease, no prospective studies on treatment of CAPS have been undertaken. Complement inhibition may be of added value in the treatment of CAPS, but its position is not well established yet.40 The recently published international guidelines are largely based on expert opinion.41

Figure 2.

Proposed algorithm for treatment of CAPS. CAPS, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome; INR, international normalised ratio. (Modified from Cervera et al 39).

Patients’ unmet needs

On diagnosis of APS there are two reactions the patient experiences: ‘dismay’ and ‘surprise’.

Regarding ‘surprise’, women of childbearing age should know about the pathology and its possible complications, without alarmism. Non-immunologists should also understand APS and its symptoms: it is difficult to diagnose rapidly and the patient can suffer multiple traumatic events (such as multiple miscarriages), which might otherwise be avoided. It is also difficult for patients to identify suitable specialists, as the symptoms are not always easily interpretable. Again, this could be addressed through more widespread knowledge of the disease. On confirmation of diagnosis it is important for the patient and family to understand the disease’s possible effects and the purpose of each drug. This information would engage the patient and family in treatment, rather than ‘imposing it from above’ and would help affront lengthy and complex treatment, which is a burden on the patient. The treatment should be tailored to the person, after careful study of the clinical history.

Regarding ‘dismay’, a ‘network’ must be created between specialist, general practitioner, family, friends and coworkers, as solitude can be a great obstacle in dealing with the pathology, its possible effects and the need for treatment. The effects of APS also often have a negative impact on the patient’s life: the resulting events, as well as the time and the energy consumed by the pathology, commonly delay career advancement or building a family. It can even be difficult to withstand the financial burden (eg, for specialist consultancies, for INR home measurement systems), especially without structured support from a public health service. Lastly, doctors could be more encouraging towards patients with APS: discouraging people from having children or creating anxiety regarding possible complications helps neither the patient nor research. Despite a ‘difficult’ clinical picture, the positive results obtained can often surprise doctors as well as the patient himself.

Conclusions

With APS being a rare disease, not many well-designed clinical trials have been performed, resulting in a lack of reliable clinical data. With no formal clinical guidelines in place, diagnosis and treatment of APS is largely based on consensus and expert opinion.

In the current review process, we were able to identify six main areas of uncertainty for patient’s diagnosis and care, namely: laboratory tests and their standardisation, primary prophylaxis, thrombosis treatment, pregnancy and pregnancy-related issues management, non-criteria manifestations and CAPS. The 17 papers evaluated allocated to the respective areas could be useful in providing background information for a future clinical guideline. However, some limitations concerning these papers were noted. First, some papers had a primary focus on systemic lupus erythematosus, including only scarce data and recommendations on APS. Second, most of the included papers were rather outdated, with only six articles published in the last 3 years, while others were published 5–9 years and one 14 years ago.

In conclusion, we were able to identify 17 papers that provide important and helpful data on APS that should be taken into account for the development of a future clinical guideline. However, much more well-designed clinical research is needed to answer the still many open questions in this disease. Patients’ unmet needs deserve special interest in future research. At present, the European League Against Rheumatism installed a task force, working on a clinical guideline for the management of APS. Large international collaborations will be necessary to have enough statistical power in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the members of the Steering Committee of the ERN ReCONNET for the huge commitment during this work. A special thank goes to all the members of the ERN ReCONNET team for providing support during all the phases of the Work Package 3.

Footnotes

Contributors: LM, NCC, TA: substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data; substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CAS, TR, ZA, LC, AD, DL, FL, CM, CMM, VR, MT, JMvL, SB, VS, AV, MM: substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AT, MB, GB, RC, NCC, TD, FJE, IG, EH, PM, MFMF, LM, MS, MC: substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This publication was funded by the European Union’s Health Programme (2014-2020).

Disclaimer: ERN ReCONNET is one of the 24 European Reference Networks (ERNs) approved by the ERN Board of Member States. The ERNs are co-funded by the European Commission. The content of this publication represents the views of the authors only and it is their sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. The AGREE Collaboration. Appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation, 2001. Available from: http://www.agreetrust.org/

- 2. Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Andreoli L, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force. Report on antiphospholipid syndrome laboratory diagnostics and trends. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:917–30. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, et al. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol 2012;157:47–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lakos G, Favaloro EJ, Harris EN, et al. International consensus guidelines on anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein I testing: report from the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1–10. 10.1002/art.33349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pengo V, Tripodi A, Reber G, et al. Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:1737–40. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03555.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alarcón-Segovia D, Boffa MC, Branch W, et al. Prophylaxis of the antiphospholipid syndrome: a consensus report. Lupus 2003;12:499–503. 10.1191/0961203303lu388oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. report of a task force of the EULAR standing committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:195–205. 10.1136/ard.2007.070367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertsias GK, Ioannidis JP, Aringer M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus with neuropsychiatric manifestations: report of a task force of the EULAR standing committee for clinical affairs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:2074–82. 10.1136/ard.2010.130476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Groot N, de Graeff N, Avcin T, et al. European evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of paediatric antiphospholipid syndrome: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1637–41. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-211001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Cuadrado MJ, Ruiz-Arruza I, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the prevention and long-term management of thrombosis in antiphospholipid antibody-positive patients: report of a task force at the 13th International Congress on antiphospholipid antibodies. Lupus 2011;20:206–18. 10.1177/0961203310395803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crowther MA, Wisloff F. Evidence based treatment of the antiphospholipid syndrome II. Optimal anticoagulant therapy for thrombosis. Thromb Res 2005;115:3–8. 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meroni PL, Moia M, Derksen RH, et al. Venous thromboembolism in the antiphospholipid syndrome: management guidelines for secondary prophylaxis. Lupus 2003;12:504–7. 10.1191/0961203303lu389oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, et al. VTE, Thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy. Chest 2012;141:e691S–e736S. 10.1378/chest.11-2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Jesus GR, Agmon-Levin N, Andrade CA, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force report on obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:795–813. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huchon C, Deffieux X, Beucher G, et al. Pregnancy loss: French clinical practice guidelines. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;201:18–26. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andreoli L, Bertsias GK, Agmon-Levin N, et al. EULAR recommendations for women's health and the management of family planning, assisted reproduction, pregnancy and menopause in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and/or antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:476–85. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abreu MM, Danowski A, Wahl DG, et al. The relevance of "non-criteria" clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Technical Task Force Report on Antiphospholipid Syndrome Clinical Features. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:401–14. 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus 2003;12:530–4. 10.1191/0961203303lu394oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Espinosa G, Cervera R. Current treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome: lights and shadows. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:586–96. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pengo V, Ruffatti A, Tonello M, et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome: antibodies to Domain 1 of β2-glycoprotein 1 correctly classify patients at risk. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:782–7. 10.1111/jth.12865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meneghel L, Ruffatti A, Gavasso S, et al. Detection of IgG anti-Domain I beta2 Glycoprotein I antibodies by chemiluminescence immunoassay in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 2015;446:201–5. 10.1016/j.cca.2015.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zohoury N, Bertolaccini ML, Rodriguez-Garcia JL, et al. Closing the serological gap in the antiphospholipid syndrome: the value of ‘non-criteria’ antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1597–602. 10.3899/jrheum.170044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arnaud L, Mathian A, Ruffatti A, et al. Efficacy of aspirin for the primary prevention of thrombosis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies: an international and collaborative meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:281–91. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Erkan D, Harrison MJ, Levy R, et al. Aspirin for primary thrombosis prevention in the antiphospholipid syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in asymptomatic antiphospholipid antibody-positive individuals. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2382–91. 10.1002/art.22663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Erkan D, Unlu O, Sciascia S, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in the primary thrombosis prophylaxis of antiphospholipid antibody positive patients without systemic autoimmune disease. Lupus 2018;27 10.1177/0961203317724219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nuri E, Taraborelli M, Andreoli L, et al. Long-term use of hydroxychloroquine reduces antiphospholipid antibodies levels in patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Immunol Res 2017;65:17–24. 10.1007/s12026-016-8812-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taraborelli M, Reggia R, Dall'Ara F, et al. Longterm Outcome of patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome: a retrospective multicenter study. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1165–72. 10.3899/jrheum.161364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Erkan D, Aguiar CL, Andrade D, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies: task force report on antiphospholipid syndrome treatment trends. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:685–96. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van den Hoogen LL, Fritsch-Stork RD, Versnel MA, et al. Monocyte type I interferon signature in antiphospholipid syndrome is related to proinflammatory monocyte subsets, hydroxychloroquine and statin use. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:e81 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emmi G, Urban ML, Scalera A, et al. Repeated low-dose courses of rituximab in SLE-associated antiphospholipid syndrome: Data from a tertiary dedicated centre. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:e21–e23. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tenti S, Guidelli GM, Bellisai F, et al. Long-term treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome with intravenous immunoglobulin in addition to conventional therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31:877–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kronbichler A, Frank R, Kirschfink M, et al. Efficacy of eculizumab in a patient with immunoadsorption-dependent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report. Medicine 2014;93:e143 10.1097/MD.0000000000000143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pengo V, Denas G, Zoppellaro G, et al. Rivaroxaban vs warfarin in high-risk patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood 2018. 10.1182/blood-2018-04-848333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mekinian A, Lazzaroni MG, Kuzenko A, et al. The efficacy of hydroxychloroquine for obstetrical outcome in anti-phospholipid syndrome: Data from a European multicenter retrospective study. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:498–502. 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bramham K, Thomas M, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. First-trimester low-dose prednisolone in refractory antiphospholipid antibody-related pregnancy loss. Blood 2011;117:6948–51. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruffatti A, Favaro M, Hoxha A, et al. Apheresis and intravenous immunoglobulins used in addition to conventional therapy to treat high-risk pregnant antiphospholipid antibody syndrome patients. A prospective study. J Reprod Immunol 2016;115:14–19. 10.1016/j.jri.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lefkou E, Mamopoulos A, Dagklis T, et al. Pravastatin improves pregnancy outcomes in obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome refractory to antithrombotic therapy. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2933–40. 10.1172/JCI86957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Erkan D, Vega J, Ramón G, et al. A pilot open-label phase II trial of rituximab for non-criteria manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:464–71. 10.1002/art.37759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cervera R, Rodríguez-Pintó I, Espinosa G. The diagnosis and clinical management of the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun 2018;92:1–11. 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shapira I, Andrade D, Allen SL, et al. Brief report: induction of sustained remission in recurrent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome via inhibition of terminal complement with eculizumab. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2719–23. 10.1002/art.34440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Legault K, Schunemann H, Hillis C, et al. McMaster RARE-Bestpractices clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and management of the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2018:1656–64. 10.1111/jth.14192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]