Abstract

Coinfection with leishmaniasis and schistosomiasis has been associated with increased time to healing of cutaneous lesions of leishmaniasis. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of Leishmania braziliensis infection on co-cultures of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs) with autologous lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis and patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis. MoDCs were differentiated from peripheral blood monocytes, isolated by magnetic beads, infected with L. braziliensis, and co-cultured with autologous lymphocytes. Expression of HLA-DR, CD1a, CD83, CD80, CD86, CD40, and the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) on MoDCs as well as CD28, CD40L, CD25, and CTLA-4 on lymphocytes were evaluated by flow cytometry. The production of the cytokines IL-10, TNF, IL-12p40, and IFN-γ were evaluated by sandwich ELISA of the culture supernatant. The infectivity evaluation was performed by light microscopy after concentration of cells by cytospin and Giemsa staining. It was observed that the frequency of MoDCs expressing CD83, CD80, and CD86 as well as the MFI of HLA-DR were smaller in the group of patients with schistosomiasis compared to the group of patients with leishmaniasis. On the other hand, the frequency of IL-10R on MoDCs was higher in patients with schistosomiasis than in patients with leishmaniasis. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from patients with schis-tosomiasis presented a lower frequency of CD28 and a higher frequency of CTLA-4 compared to lymphocytes from patients with leishmaniasis. Levels of IL-10 were higher in the supernatants of co-cultures from individuals with schistosomiasis compared to those with leishmaniasis. However, levels of TNF, IL-12p40, and IFN-γ were lower in the group of individuals with schistosomiasis. Regarding the frequency of MoDCs infected by L. braziliensis after 72 h in culture, it was observed that higher frequencies of cells from patients with schistosomiasis were infected compared to cells from patients with leishmaniasis. It was concluded that MoDCs from patients with schistosomiasis are more likely to be infected by L. braziliensis, possibly due to a lower degree of activation and a regulatory profile.

Keywords: Schistosomiasis, Leishmaniasis, Dendritic cells, Leishmania braziliensis

1. Introduction

Parasitic infectious diseases, such as schistosomiasis caused by Schistosoma mansoni and cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) are a serious public health problem presenting a high morbidity rate. The immunopathogenesis of chronic schistosomiasis is predominated by the Th2/regulatory immune response, which is important for the elimination of the worm and the containment of Schistosoma mansoni eggs. At the same, this immune response appears to be associated with the long-term survival of the parasite in host tissues (Pearce and MacDonald, 2002). In cutaneous leishmaniasis the predominant immune response is the Th1/inflammatory type that is associated with parasitic elimination, but is also responsible for the development of the characteristic lesion observed in the disease (Ribeiro-de-Jesus et al., 1998; Antonelli et al., 2005). Studies have demonstrated that helminth infection has the ability to modulate the immune response in immune-mediated diseases, such as asthma (Medeiros et al., 2003; Araujo et al., 2004a,b), Crohn’s disease (Elliott et al., 2007), type 1 diabetes mellitus (Cooke et al., 1999), HTLV infection (Porto et al., 2005; Lima et al., 2013), and leishmaniasis (O’Neal et al., 2007; Bafica et al., 2011). It has been shown that infection by Schistosoma mansoni or its products are able to modulate the Th1 inflammatory response (Actor et al., 1993; Sabin et al., 1996) involved in some immune-mediated diseases. In an experimental model, animals coinfected with Leishmania and Schisto-soma had larger lymph nodes than monoinfected animals (Yole et al., 2007). Another study using BALBc mice coinfected with L. major and S. mansoni showed a reduction in lesion size after the combined treatment with a pentavalent antimonial and praziquantel compared to separately treated animals (Khayeka-Wandabwa et al., 2013).

In human cutaneous leishmaniasis, the modulation of the immune response induced by helminth infection, including infection by Schistosoma mansoni, has been associated with changes in the immune response and an increase in healing time of cutaneous lesions in humans (O’Neal et al., 2007). A human study showed that a total of 51.1% of patients coinfected with helminths and L. braziliensis had persistent lesions on day 90 of antimonial treatment compared to 62.2% in the group who first had their helminths treated. The failure rate in both groups was 57%. The mean cure time was 88 days in the control group and 98 days in the group that received anthelmintic treatment. Al-though there was no statistically significant difference, patients who received early anthelmintic treatment took longer to heal their lesions than patients in the untreated group. This study shows that the early introduction of anthelmintic therapy does not improve clinical out-comes in patients coinfected with helminths and L. braziliensis (Newlove et al., 2011). A recent study showed that patients coinfected with intestinal helminths and Leishmania braziliensis had a higher frequency of tegumentary lesions and took longer to heal compared to patients without helminth infection (Azeredo-Coutinho et al., 2016). These co-infected individuals also presented more therapeutic failures or relapses than patients not infected with helminths. These results suggest that intestinal infections with helminths interfere with the clinical course of tegumentary leishmaniasis (Azeredo-Coutinho et al., 2016).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are recognized for their ability to sensitize naïve T lymphocytes and for contributing to the functional differentiation of regulatory T cells (Yamazaki et al., 2003), as well as being important sources in the production of cytokines and the presentation of parasite antigens to T cells (de Saint-Vis et al., 1998). Early events in Leishmania infection involving macrophages and dendritic cells in the presentation of parasite antigens to T cells and in the production of cytokines likely influence host response and the course of infection. It is understood that the Th1 response is important for infection control, but Th1 cytokines may also be related to the pathogenesis of disease. Therefore, it is important to have a balance between Th1 cells and regulatory T cells, not a single polarized type of response, as these regulatory mechanisms are important in maintaining the tissue integrity of the host against an exaggerated inflammatory response (Baratta-Masini et al., 2007; Reis et al., 2007). The Th2-type response may also be dependent on DCs. Several pathogens such as Schistosoma sp. and fungi provoke DCs to induce a Th2 response. This response appears to be the result of the action of some parasitic antigens on DCs (d’Ostiani et al., 2000; MacDonald et al., 2001; Bacci et al., 2002).

Experimental infection of dendritic cells by L. braziliensis promastigotes induces the production of high levels of TNF, which may contribute to a local parasitic control response (Carvalho et al., 2008). The type 1 immune response pattern with IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-12 production has been associated with the control of infection by macrophage activation and parasitic destruction in human leishmaniasis (Roberts, 2005; Ameen, 2010). On the other hand, cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β favor parasitic multiplication, inhibiting the production of NO by IFN-γ-activated macrophages and also inhibiting the differentiation of T lymphocytes into Th1 cells and their consequent production of IFN-γ and TNF (Baratta-Masini et al., 2007; Matos et al., 2007). CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes act as a source of cytokines involved in the pro-cess of macrophage activation in leishmaniasis (Da-Cruz et al., 2002). DCs may influence CD4+ T cell responses whether they be type 1 (Th1) or type 2 (Th2) (Moser and Murphy, 2000). The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of Leishmania braziliensis infection on monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs) co-cultured with autologous lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis and cutaneous leish-maniasis.

Since studies have shown that lesions of individuals coinfected by Leishmania sp. and helminths take longer to heal (O’Neal et al., 2007) and since an experimental model has shown that the dual treatment of leishmaniasis and schistosomiasis is related to a reduction in lesion size at the onset of the disease and an increase in lesion size at later stages of disease (La Flamme et al., 2002), the understanding of the im-munological mechanisms that contribute to the aggravation of the in-flammatory process mediated by DCs and lymphocytes will help in understanding the mechanisms associated with the severity of leish-maniasis in coinfected individuals.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Three groups of patients were included in the study: one group of patients with schistosomiasis (n = 6), another group of patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis (n = 12), and one group of healthy individuals (n = 7). Individuals with schistosomiasis are residents of an endemic area, located in the municipality of Conde in the state of Bahia, Brazil. In this group, 75% of the individuals were male and 25% female, with a mean age of 35.5 ± 22.4 years. The diagnostic criteria were based on the presence of Schistosoma mansoni eggs in at least one fecal para-sitological sample by the Hoffman method. All had high parasitic load (> 200 epg) by the Kato-Katz method. Twelve patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) living in an endemic area, known as Corte de Pedra, located in the southeastern region of the state of Bahia, Brazil, were included in the group of patients with leishmaniasis, with 67% of the patients male and 33% female and a mean age of 33.5 ± 14.5 years. Diagnostic criteria included a clinical presentation characteristic of CL (granulomatous lesions on the skin), parasite isolation, delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) in response to soluble Leishmania antigen (SLA), or histological characteristics of CL in skin biopsy. Three fecal samples from each individual were examined using the Hoffman sedimentation method to exclude S. mansoni-infected individuals from the CL and healthy control groups. To rule out the effect of previous S. mansoni exposure in immunological assays, we also measured the levels of serum-specific IgE to S. mansoni soluble adult worm antigen (SWAP). Individuals from the CL group and healthy controls were negative for S. mansoni infection or exposure to this parasite antigen. Of the 12 CL patients evaluated, 42% had only one lesion characteristic of leishma-niasis and 58% presented with between two and four lesions. The healthy control group consisted of individuals residing in Salvador, 70% of whom were male and 30% of whom were female, with a mean age of 28 ± 15 years.

The Ethics Committee of the Universidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB) has approved the present study. All individuals who were re-cruited and agreed to participate in the study signed an informed consent form.

2.2. In vitro generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs), L. braziliensis infection, and co-culture with autologous lymphocytes

Dendritic cells from patients with schistosomiasis and leishmaniasis were differentiated from monocytes (monocyte-derived dendritic cells, MoDCs). Whole blood was collected by venipuncture and collected in a tube containing sodium heparin. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained by the Ficoll-Hypaque gradient and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL in complete RPMI 1640 (100 μL/mL gentamicin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 30 mM HEPES) containing 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Monocytes (CD14+) were isolated from PBMCs using magnetic beads (Monocyte Isolation Kit II human, MACS, Miltenyi Biotec) by negative selection, using anti-CD3, CD56, CD16, CD19, and Glycophorin A monoclonal antibodies. Lymphocytes re-sulting from monocyte separation by magnetic beads were stored at −70 °C in DMSO + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 7 days for further co-cultivation with MoDCs. Monocytes were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 7 days with 3 mL/well of complete RPMI containing 800IU/mL IL-4 (Peprotech) and 50 ng/mL GM-CSF (Peprotech) in 6-well plates where they were cultured at a concentration of 2 × 106 monocytes/mL (50 μL) for differentiation into dendritic cells. The purity of the monocytes was > 80%. Purity of the lymphocytes was > 90%. After 7 days of culture, the MoDCs (CD11c+) were collected by washing the wells 3x with RPMI medium. Then, the MoDCs were infected by promastigotes of L. braziliensis that were previously incubated with RPMI + 10% FBS medium, at a concentration of 1:5 for a period of 2 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After this time the cells were washed 3x with complete RPMI medium in order to remove those promastigotes that did not infect any cells. Lymphocytes were then thawed slowly in a water bath at 37 °C, washed with 1x PBS, and adjusted for co-cultivation with the dendritic cells for a ratio of 10 lymphocytes to one MoDC.

2.3. Evaluation of the phenotype and activation status of dendritic cells and lymphocytes after infection with Leishmania braziliensis

Expression of activation and regulation molecules by MoDCs and lymphocytes was evaluated by flow cytometry. The percentage of CD11c+ cells (MoDCs) for all experiments was ≥90% (data not shown). Briefly, MoDCs and lymphocytes were collected after 24 h of culture and labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to eval-uate cell surface molecules. MoDCs were collected by centrifugation at 1100 rpm for 10 min and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium con-taining 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, heat inactivated) (Gibco, Invitrogen). Dendritic cells (DCs) were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human monoclonal antibodies against the following cell surface molecules: CD11c-APC (clone 3.9), CD1a-FITC (clone HI149), IL-10Rα-PE (polyclonal), CD40-PerCP-e Fluor 710 (clone 5C3), CD80-PerCP-e Fluor 710 (clone 2D10.4), CD86-PE (clone IT2.2), CD83-PE-Cy7 (clone HB15e), and HLA-DR-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone LN3) (all from eBioscience, California). Lymphocytes were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human monoclonal antibodies against the following cell surface molecules: CD3-PE-Cy7 (clone UCHT1) or CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone SK7), CD4-APC (clone OKT4), CD8-FITC (clone RPA-T8), CTLA-4-PE (clone 14D3), CD40L-PE (clone 24–34), CD25-PE-Cy7 (clone BC96), and CD28-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone CD28.2) (all from eBioscience, California). They were then analyzed for 100,000 events per sample by flow cytometer (FACSCanto, Becton Dickinson). Limits for positive markers were defined based on negative populations and isotype con-trols (data not shown).

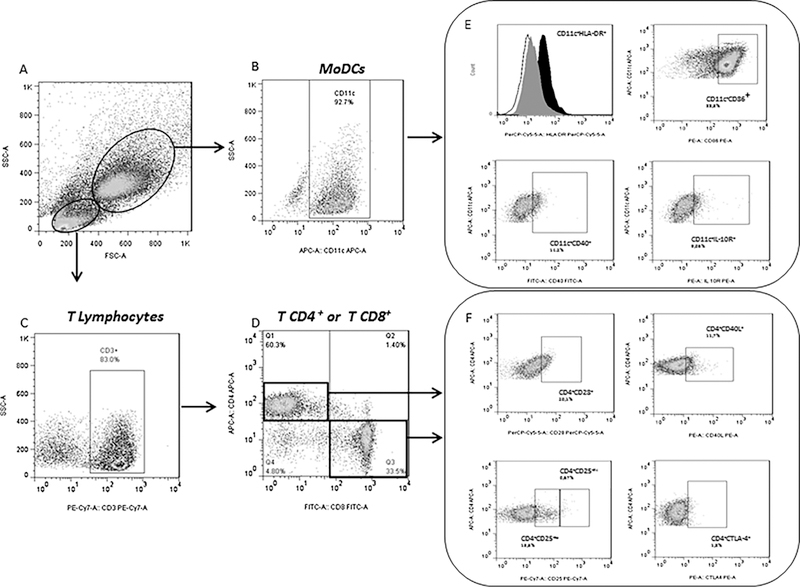

The frequency of positive cells was analyzed using the FlowJo™ program (Tree Star, USA). The region containing the population of MoDCs and lymphocytes was defined by non-specific fluorescence using forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) signal intensities, mea-suring cell size and granularity, respectively (Fig. 1A). Dendritic cells were defined based on their granularity and CD11c expression (Fig. 1B), whereas lymphocytes were defined based on their granularity and CD3 expression (Fig. 1C). CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocyte sub-populations evaluated within the lymphocyte population (Fig. 1D). A representative gating of surface cell markers on dendritic cells and lymphocytes of one experiment are shown in the same figure (Fig. 1E and F, respectively).

Fig. 1.

(A) Selection strategy via a non-specific fluorescence densitometry plot for size (FSC) and cell granularity (SSC) to identify populations of dendritic cells and lymphocytes; (B) The marker of MoDCs (CD11c+) evaluated within the MoDC population; (C) Total T cell populations. (D) The subpopulations CD4+ and CD8+ gated within the T lymphocytes; (E) A representative gating of cell surface markers at the dendritic cells (HLA-DR, CD86, CD40, and IL-10R); (F) A A representative gating of surface cell markers at TCD4+ lymphocytes (CD28, CD40L, CD25, CTLA-4).

2.4. Determination of cytokine levels

Levels of IL-10, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and TNF were evaluated in the supernatants of co-cultures of MoDCs and lymphocytes, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Briefly, plates (Nunc-Immuno Plate MaxiSorp Surface, Denmark) were sensitized for 4 h at 4 °C with 4 μg/mL of human anti-cytokine monoclonal antibody (anti-IL-10, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and TNF). The following day, after washing the plates with PBS/Tween 0.05%, blockade of non-specific binding was performed with PBS + 0.01% bovine albumin for 2 h at room temperature. Three washes were performed with PBS/ Tween 0.05% and then the samples, blanks, and standards were added which were incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The plate was washed again 3 times and biotinylated human anti-cytokine detection antibody (2 μg/mL) was added. After incubating for one hour at room temperature the plates were washed 4 times and the conjugate (streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase) was added. The plate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, the substrate (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine + H2O2 + dimethyl sulfoxide) was added and the plate was incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The reaction was interrupted by the addition of H2SO4 (8 M). Optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm (Spectramax, Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA) and the values were converted to pg/mL based on the standard curve (Soft Max Pro 5.0 Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the program GraphPadPrism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA USA). Differences between fre-quencies and infectivity of MoDCs, lymphocyte frequencies, and cyto-kine levels between groups were assessed by non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal Wallis test with Dunns post test). The frequencies of positive cells were expressed as a median (minimum and maximum) of the percentage or by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Cytokine con-centrations were expressed as a mean and standard deviation (pg/mL). Statistical significance was established in the 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

3.1. Profile of activation, maturation, co-stimulatory, and regulatory molecules in MoDCs from patients with schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and controls

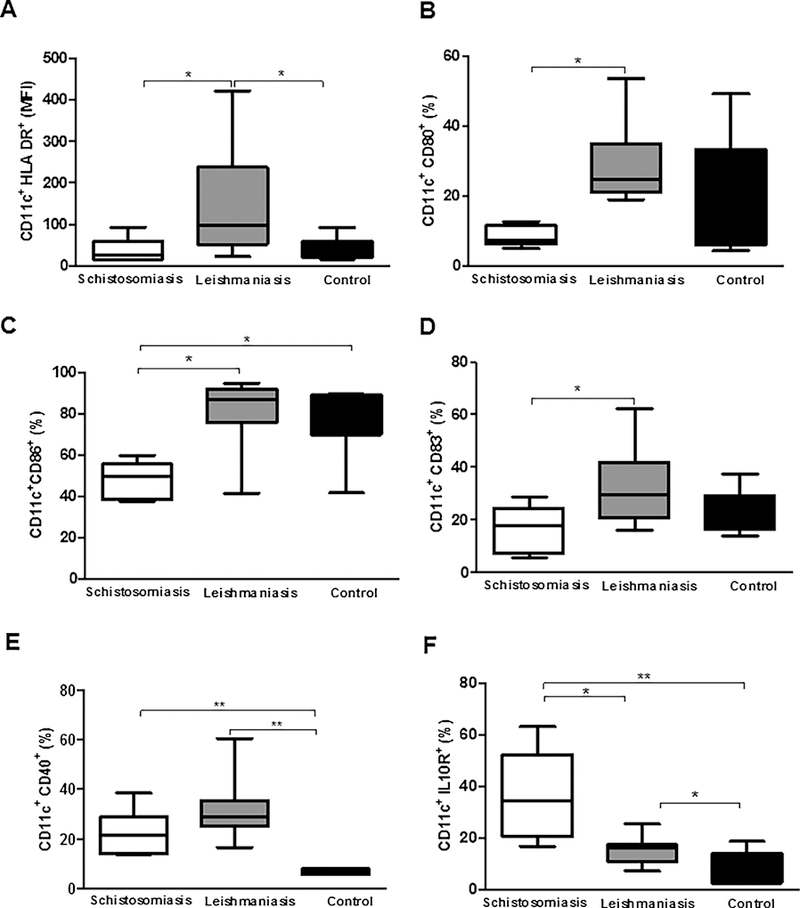

MoDCs from patients with schistosomiasis and control subjects infected with L. braziliensis had a lower mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the HLA-DR activation molecule [36.6 (9.04–64.30 MFI); 31.3 (16–93 MFI), respectively] compared to MoDCs from patients with leishmaniasis [46.7 (5.37–76.6 MFI); p < 0.05, Fig. 2A]. The frequency of MoDCs expressing CD80 co-stimulatory molecules was lower in patients with schistosomiasis [CD80: 7.29% (5.09–12.70)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis [CD80: 24.75% (19.00–53.60%); P < 0.05, Fig. 2B]. It was also observed that the frequency of MoDCs expressing CD86 co-stimulatory molecules was lower in patients with schistosomiasis [CD86: 49.45% (37.60–59.90%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis or healthy controls [CD86: 86.85% (41.40–97.805%); 75% (42–90%), respectively; p < 0.05, Fig. 2C]. When evaluating the maturation of MoDCs we observed that the frequency of cells expressing CD83 was lower in patients with schistosomiasis [CD83: 17.6% (5.73–28.60%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis [CD83: 29.60% (16.10–62.60%); p < 0.05, Fig. 2D]. The frequency of MoDCs expressing CD40 co-stimulatory molecules was higher in patients with schistosomiasis [CD40: 21% (14–39%)] and patients with leishmaniasis [CD40: 29% (17–60%)] compared to healthy controls [CD40: 7% (6–8%); p < 0.005, Fig. 2E]. Finally, in the phenotypic evaluation of MoDCs, we observed an increase in the frequency of these cells expressing the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) regulatory molecule in patients with schistosomiasis [34.45% (16.80–63.10%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis [16.15% (7.18–25.40%); p < 0.05, Fig. 2F]. The frequency of MoDCs expressing IL-10R was greater in patients with schistosomiasis and patients with leishmaniasis compared to healthy controls [9% (3–19%); P < 0.05, Fig. 2F]. There was no difference in the frequency of MoDCs expressing CD1a between the groups of patients evaluated (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of activation, co-stimulatory, maturation, and regulatory molecules in MoDCs from patients with schistosomiasis and leishmaniasis infected with L. braziliensis and co-cultured with autologous lymphocytes. (A) CD11c+HLA-DR+ (MFI), (B) CD11c+CD80+ (%), (C) CD11c+CD86+ (%), (D) CD11c+CD83+ (%), (E) CD11c+CD40+ (%), and (F) CD11c+IL-10R+ (%). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.005. Kruskal Wallis test.

3.2. Evaluation of the profile of activation and regulatory molecules in CD4+ helper T lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and controls

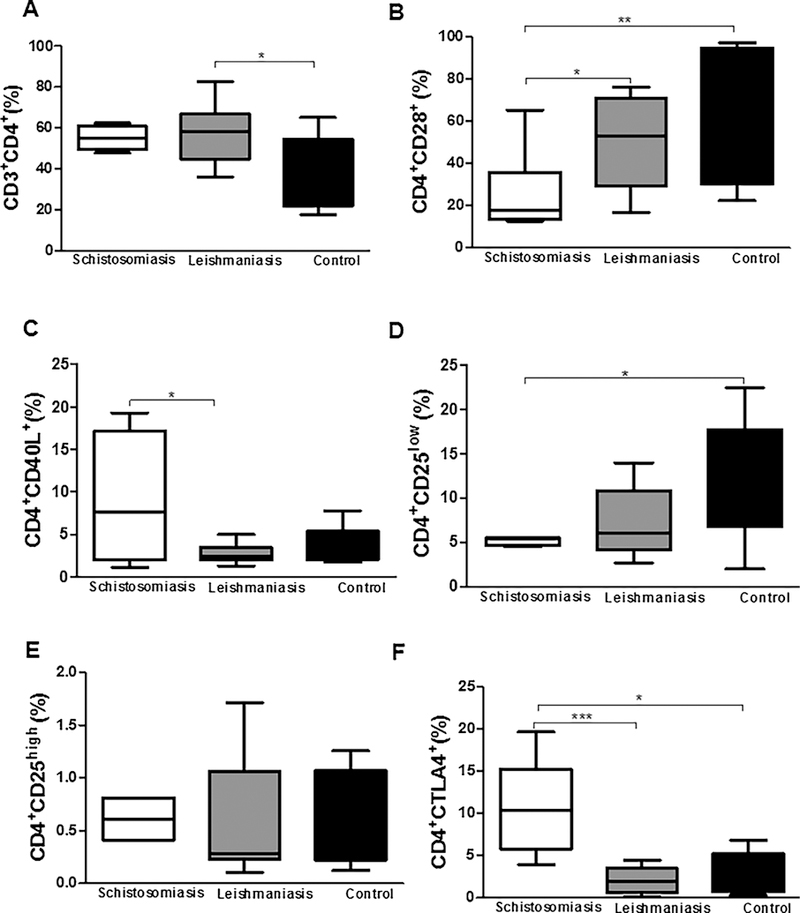

When evaluating T lymphocyte profiles between the groups, it was observed that patients with leishmaniasis presented a higher frequency of CD4+ T lymphocytes [58.00% (36.00–82.50%)] compared to healthy controls [45% (18–65%); p < 0.05, Fig. 3A]. Regarding the activation profile of these CD4+ T lymphocytes, we observed that patients with schistosomiasis presented a lower frequency of the CD28 activation molecule [17.80% (12.60–65.20%)] compared to leishmaniasis patients or healthy controls [52.70% (16.70–76.20%); 69% (22–97%); p < 0.05 and p < 0.005, respectively, Fig. 3B]. Regarding the frequencies of CD4+CD40L+ lymphocytes, patients with schistosomiasis had a higher frequency of these surface markers [7.59% (1.15–19.30%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis [2.40% (1.27–4.96%); p < 0.05, Fig. 3C]. Concerning CD4+CD25+ lymphocytes, it was observed that patients with schistosomiasis had a lower frequency of these surface markers [5.4% (4.6–5.5%)] compared to healthy controls [8.1% (2.0–22%); p < 0.05, Fig. 3D]. There was no difference between the three groups of patients regarding CD4+CD25high T lymphocyte frequency (Fig. 3E). Regarding CTLA-4, a molecule associated with regulation of the immune response, patients with schistosomiasis had a higher frequency of CD4+CTLA-4+ lymphocytes [7.72% (3.93–10.80)] when compared to patients with leishmaniasis or healthy controls [1.93% (0.10–4.50), 2.5% (0.4–6.8); p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 3F].

Fig. 3.

Frequency of CD3+CD4+ T lymphocytes (A) expressing CD4+CD28+ co-stimulatory molecules (B), CD4+CD40L+ (C), CD4+CD25low (D), CD4+CD25high (E), and CD4+CTLA-4+ (F) after 24 h of co-culture with MoDCs infected for 2 h by L. braziliensis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.001. Kruskal Wallis test.

3.3. Evaluation of the profile of activation and regulatory molecules in CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and controls

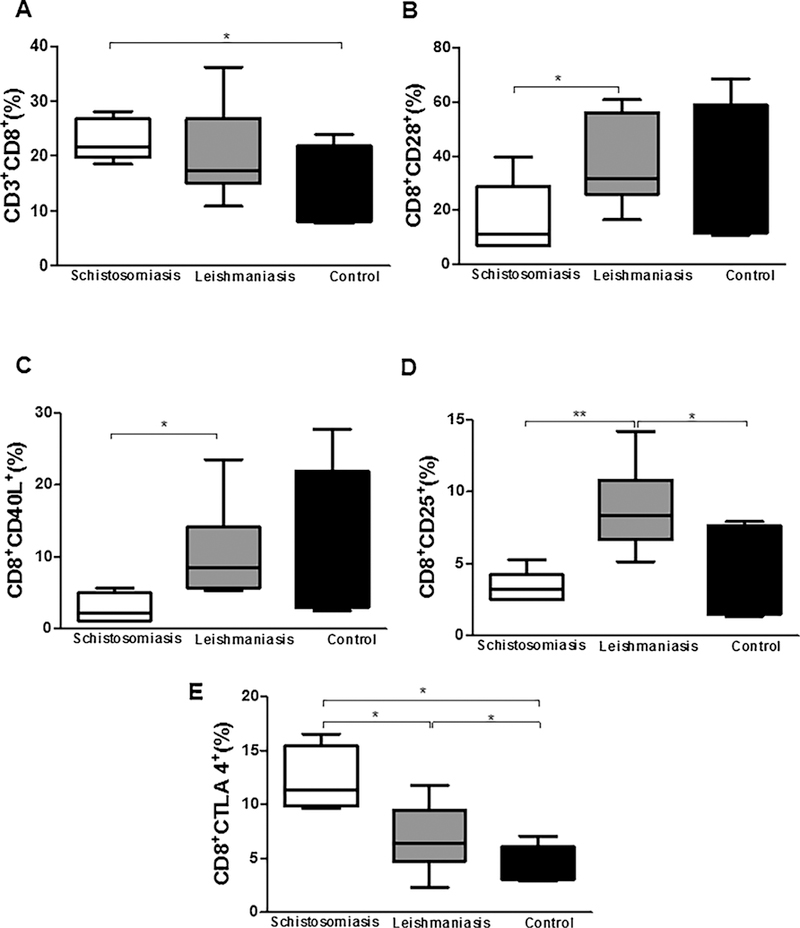

When we evaluated the profile of CD8+ T lymphocytes between groups, we observed that patients with schistosomiasis presented a higher frequency of these lymphocytes [22% (18–28%)] compared to healthy controls [14% (8–24%); p < 0.05, Fig. 4A]. Regarding the frequency of CD8+CD28+ T lymphocytes, we observed that patients with schistosomiasis presented a lower frequency of these cells [9.02% (6.81–17.70%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis [34.55% (23.70–60.90%); p < 0.05, Fig. 4B]. We also observed a lower frequency of CD40L in CD8+ T lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis [1.21% (1.12–3.01%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis [8.44% (5.30–23.50%); p < 0.05, Fig. 4C]. Concerning to CD8+CD25+ T lymphocytes, we observed a higher frequency of these cells in the group of patients with leishmaniasis [8.34% (5.13–14.20%)] compared to the group of patients with schistosomiasis or healthy controls [3.20% (2.52–5.31%), 2% (1–8%); p < 0.005 and p < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 4D]. In contrast, CD8+ T lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis presented a greater frequency of CTLA-4 expression [11.3% (9.61–16.5%)] compared to patients with leishmaniasis or healthy controls [6.45% (2.25–11.80%), 3% (3–7%), respectively; p < 0.05, Fig. 4F]. We observed a higher frequency of CD8+CTLA-4+ T lymphocytes in patients with leishmaniasis than in healthy controls (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Frequency of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes (A) expressing CD8+CD28+ co-stimulatory molecules (B), CD8+CD40L+ (C), CD8+CD25+ (D), and CD8+CTLA-4+ (E) after 24 h of co-culture with MoDCs infected for 2 h by L. braziliensis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.001. Kruskal Wallis test.

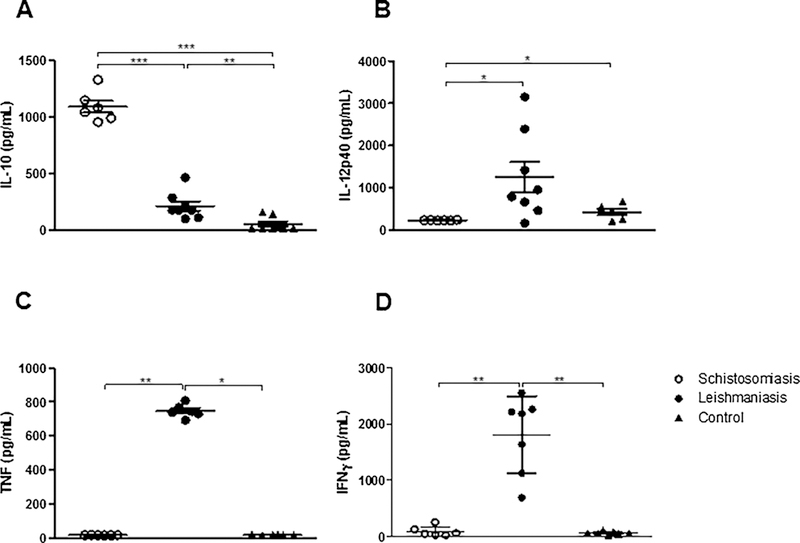

3.4. Evaluation of cytokine production in co-cultures of dendritic cells infected with L. braziliensis and autologous lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and healthy controls

When we evaluated the production of cytokines in the supernatants of co-cultures of MoDCs infected with Leishmania braziliensis and au-tologous lymphocytes, we observed that the cultures of patients with schistosomiasis presented higher levels of IL-10 (1090 ± 134.6 pg/mL) compared to patients with leishmaniasis or healthy controls [171 ± 134 pg/mL; 52 ± 59 pg/mL, respectively; p < 0.001, Fig. 5A). We observed that cultures from patients with leishmaniasis presented higher IL-10 levels compared to healthy controls (Fig. 5A). Concerning IL-12p40, TNF, and IFN-γ in supernatants from infected MoDCs and autologous lymphocyte co-cultures, we observed lower levels of IL-12p40 (235.9 ± 8.3 pg/mL), TNF (15.9 ± 0.83 pg/mL), and IFN-γ (92.7 ± 87.9 pg/mL) in cultures from the schistosomiasis patient group compared to cultures from patients with leishmaniasis (IL-12p40: 1405 ± 1003 pg/mL; TNF: 746.8 ± 38.67 pg/mL; IFN-γ: 1810 ± 684 pg/mL; p < 0.05 and p < 0.005; Fig. 5A, B, C, and D, respectively). We observed that cultures from patients with schistoso-miasis presented lower levels of IL-12p40 (235.9 ± 8.3 pg/mL) than healthy controls (426.2 ± 174.6 pg/mL; p < 0.05, Fig. 5B). We also observed that cultures from leishmaniasis patients had higher levels of TNF (746.8 ± 38.67 pg/mL) and IFN-γ (1810 ± 684 pg/mL) com-pared to healthy controls (TNF: 17 ± 3 pg/mL; IFN-γ: 63 ± 27 pg/mL; p < 0.05 and p < 0.005; Fig. 5C and D, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Production of cytokines from dendritic cell cultures infected by L. braziliensis for 2 h after 24 h of co-culture with autologous lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and controls. (A) IL-10, (B) IL-12p40, (C) TNF, and (D) INF-γ. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.001. Kruskal Wallis test.

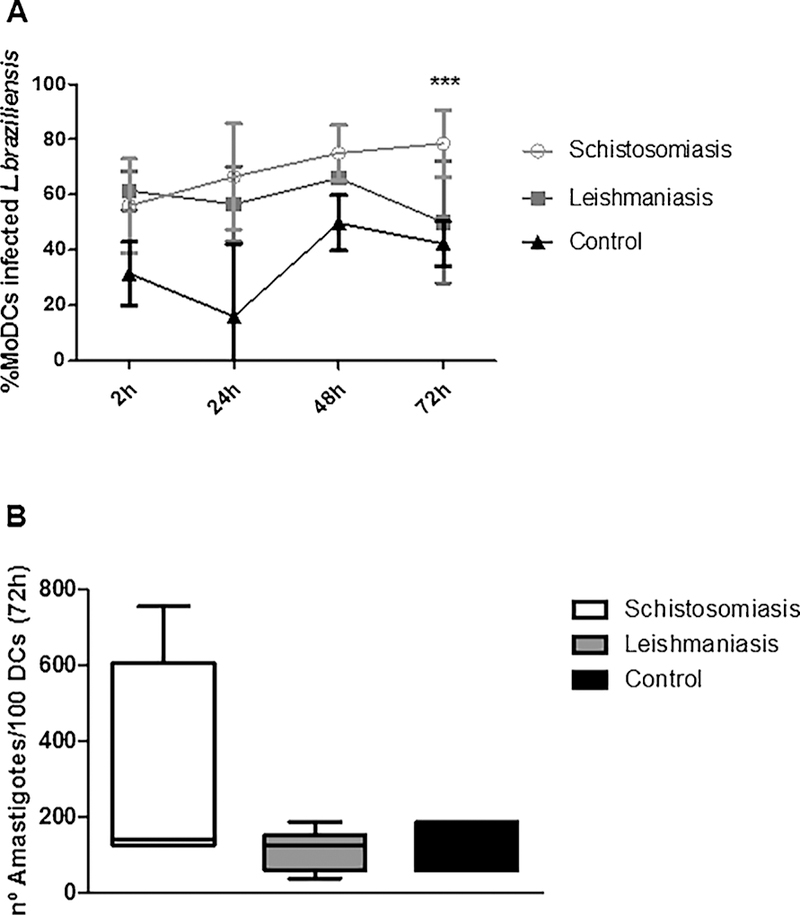

3.5. Evaluation of rate of infection of MoDCs from patients with schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and controls

Finally, we evaluated the frequency of MoDCs infected by L. braziliensis and the number of intracellular amastigotes in 100 cells surveyed. After 72 h of culture, we observed a higher frequency of L. braziliensis-infected MoDCs (78% ± 9) in the group of patients with schistosomiasis com-pared to the cells from patients with leishmaniasis or healthy controls [51% ± 20 and 42% ± 8, respectively; p < 0.001, Fig. 6A). There was no statistical difference in frequency of infected MoDCs between the three groups when cultures were evaluated at 2 h, 24 h, and 48 h post-infection. Regarding the numbers of Leishmania braziliensis amastigotes in 100 MoDCs evaluated 2 h, 24 h, 48 h (data not shown), and 72 h (Fig. 6B) post-infection, we observed that there was no statistical difference be-tween groups of patients with schistosomiasis compared to those with leishmaniasis. It was not possible to perform the evaluation after 96 h due to the low number of cells found.

Fig. 6.

Kinetics of the frequency of MoDCs infected for 2 h by L. braziliensis and co-cultured with autologous lymphocytes for 24h, 48h and 72h (A). Number of intracellular amastigotes in 100 cells evaluated (B) by light microscopy (100X). ***p < 0.001. Kruskal Wallis test.

4. Discussion

Few studies have evaluated the effect of co-endemicity of Schistosoma mansoni and Leishmania braziliensis. Some studies have shown that the helminth Schistosoma mansoni and protozoans of the Leishmania genus are sometimes co-endemic (Butterworth et al., 1996; O’Neal et al., 2007). Infections with Leishmania braziliensis result in localized skin lesions whose resolution depends on the development of a strong effector Th1 response (Carvalho et al., 1994). Infection with S. mansoni elicits a predominantly Th2-type immune response and during the chronic phase of infection causes an increase in the regulatory T response that is associated with parasitic control (Dunne et al., 2005). The interaction between these two pathogens in vitro was evaluated in this study by the infection of dendritic cells from patients with schistosomiasis by Leishmania braziliensis. The infection of dendritic cells from patients with schistosomiasis with L. braziliensis presented a regulatory phenotypic profile in both MoDCs and lymphocytes. We also observed that cultures from patients with schistosomiasis had a higher production of the regulatory cytokine IL-10 and a lower production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-12p40, TNF, and IFN-γ that are important for the intracellular elimination of protozoa. This less-active profile of dendritic cells along with a regulatory profile of lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis led to a higher rate of infection in these antigen-presenting cells compared to patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis.

The ability of a preexisting Th2 environment to modulate the Th1 response in vitro is important in understanding how modulation of the immune response can affect the development of the disease. The mechanism by which the immune response (Th2/Treg) induced by Schistosoma mansoni modulates the Th1 response is not fully defined. One factor that may contribute to the regulation of the Th1 response is the production of IL-10 and TGF-β (King et al., 1996). Both cytokines are produced at high levels during Schistosoma infection (Pearce et al., 1991) and may prevent the killing of Leishmania sp. by macrophages that are dependent on IFN-γ (Barral-Netto et al., 1992; Vouldoukis et al., 1997; Louzir, 1998). Our findings demonstrate that dendritic cells from patients with schistosomiasis are more readily infected by Leishmania braziliensis than those from patients with leishmaniasis. Other studies suggest the involvement of IL-10 in this susceptibility but more investigations are required to clarify these mechanisms. Reduced production of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-12 in cultures from patients with schistosomiasis may also be related to the higher rate of infection seen in dendritic cells from these patients.

Experiments have shown that previous infection by Schistosoma mansoni leads to a delay in the resolution of cutaneous lesions and parasitemia during infection with Leishmania major. This coinfection with S. mansoni resulted in a decrease in the production of IFN-γ, TNF, and NO produced by cells from draining lymph nodes after infection with L. major. On the other hand, these cells increased their production of IL-4 (La Flamme et al., 2002). In a study of coinfections with Schistosoma mansoni and hepatitis C virus, it has been shown that persistence of the virus and the development of chronic hepatitis are increased in coinfected patients (Elrefaei et al., 2003). The mechanism of helminths modulating the immune response may be related to induction of IL-10, altering the cellular immune response and contributing to the expansion of regulatory T cells (Araujo et al., 2004a,b; Taylor et al., 2005).

In this study, it was observed that MoDCs from patients with schistosomiasis that were subsequently infected by L. braziliensis presented lower HLA-DR expression compared to MoDCs from patients with leishmaniasis. There are studies showing that the dendritic cells from patients infected with S. haematobium present lower levels of HLA-DR expression compared to those not infected (Nausch et al., 2012; Everts et al., 2010). MoDCs from healthy individuals stimulated with soluble Schistosoma mansoni egg antigen (SEA) showed no difference in HLA-DR expression compared to non-stimulated cells (Reis et al., 2007). Data indicate that MoDCs stimulated with SEA in vitro exhibit a lower level of activation compared to that induced by conventional maturation stimuli, such as LPS (bacterial lipopolysaccharide) (Agrawal et al., 2003). In addition to SEA, other antigens that are part of different phases of the Schistosoma life cycle such as soluble schistosomulum stage antigen (SSA) and soluble adult worm antigen (SWA) are also unable to conventionally activate dendritic cells in an experimental model (Zaccone et al., 2003; Trottein et al., 2004). DCs from mice co-infected with S. japonicum and Plasmodium berghei show lower levels of expression of HLA-DR and CD86 than DCs from P. berghei-monoinfected mice (Wang et al., 2013). In our study, the frequencies of MoDCs ex-pressing CD80 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules and the CD83 maturation molecule were lower in patients with schistosomiasis compared to patients with leishmaniasis. Schistosoma antigens reduce the expression of MHC class II, CD80, and CD86 as well as decrease the production of IL-12 by DCs from mice stimulated with LPS (MacDonald et al., 2002a,b; Jankovic et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2012).

There was no difference between the two groups of patients regarding the frequency of MoDCs expressing CD1a and CD40. Activation of DCs by S. mansoni is promoted by the interaction CD40 and CD154 and inhibited by IL-10. DCs isolated from CD154-knockout mice infected by S. mansoni exhibited low levels of activation (Straw et al., 2003), whereas DCs isolated from IL-10-knockout mice showed a hyperactivated phenotype (McKee et al., 2004). Although DCs stimulated by SEA do not increase CD40 expression (MacDonald et al., 2001), a deficiency in this molecule or of CD154 prevents the development of a Th2 response in these mice (MacDonald et al., 2002a,b). It is known that IL-12 production and polarization of a Th1 response in DCs is mediated by CD40 (Cella et al., 1996) and its involvement may be re-lated to CD8+ T cell responses (Bennett et al., 1998; Ridge et al., 1998).

It has been demonstrated that immature dendritic cells are more efficient in inducing regulatory T cells (reviewed by Suciu-Foca et al., 2005) and that the co-cultivation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from mice with CD4+ T cells stimulated by recombinant Schistosoma japonicum rSj16 antigen interferes in the maturation of BMDCs, while inducing the polarization of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells (Sun et al., 2012).

Another study evaluating DCs from Schistosoma mansoni-infected mice showed a 2- to 3-fold increase in MHC class II, CD80, and CD40 expression compared to DCs from uninfected animals. However, IL-12 production was not noted to increase during S. mansoni infection (Straw et al., 2003). On the other hand, Toxoplasma gondii infection resulted in an increase in the expression of activation-associated molecules (MHC class II, CD80, CD86, and CD40) and promoted increased production of IL-12 by DCs (Straw et al., 2003). In this study by Straw et al., a greater activation of DCs was observed in mice infected with T. gondii com-pared to animals infected with S. mansoni (Straw et al., 2003).

Regarding the evaluation of IL-10R expression in antigen-presenting cells, an increase in the frequency of IL-10R+ MoDCs was observed in the group of patients with schistosomiasis when compared to patients with leishmaniasis. Data from our group showed that dendritic cells from patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis increased IL-10R+ expression after stimulation with Schistosoma mansoni tegument antigen (rSm29) and soluble Leishmania antigen (SLA) when compared to cultures stimulated with SLA alone (Lopes et al., 2014).

In our study, we observed that patients with schistosomiasis have a lower frequency of CD4+ T lymphocytes compared to healthy controls. Regarding the activation profile of these CD4+ T lymphocytes, we observed that patients with schistosomiasis presented a lower frequency of the CD28 activation molecule compared to CD4+ T lymphocytes from patients with leishmaniasis. There is evidence that B7:CD28 interaction may be important for the development of a Th2-type response during S. mansoni infection (Subramanian et al., 1997; Hernandez et al., 1999; Rutitzky et al., 2003). This lower expression of the marker of CD4+ T lymphocyte activation may be associated with a deficiency in the effector function required for the elimination of Leishmania.

As for the expression of CD40L in these CD4+ T lymphocytes, we observed that patients with schistosomiasis presented a higher frequency of this molecule compared to patients with leishmaniasis. In patients with schistosomiasis, we observed a higher frequency of CD4+ lymphocytes expressing CTLA-4 compared to CD4+ lymphocytes from patients with leishmaniasis. There was no difference between the two groups of patients regarding CD4+ lymphocytes expressing CD25low or CD25high. Bafica et al. showed an increase in CD4+ T lymphocytes expressing CTLA-4 in PBMCs from patients with CL when stimulated with Schistosoma mansoni antigens (Bafica et al., 2012).

Regarding the evaluation of surface molecules in CD8+ T lymphocytes, as was observed with the CD4+ T lymphocytes, a lower frequency of CD28-expressing cells was observed in the group of patients with schistosomiasis compared to the group of patients with leishmaniasis. We also observed a lower frequency of CD40L in CD8+ T lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis compared to patients with leishmaniasis. When we evaluated the expression of CD25 we observed a lower frequency of this molecule in CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis compared to patients with leishmaniasis. On the other hand, CD8+ T lymphocytes from patients with schistosomiasis presented a higher frequency of CTLA-4 than patients with leishmaniasis. In coinfections by the helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus and the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, the nematode-induced response sup-presses CD8+ T lymphocytes with decreased IFN-γ (Marple et al., 2017).

When we evaluated the production of cytokines in the supernatants of cultures of dendritic cells infected with Leishmania braziliensis and co-cultivated with autologous lymphocytes, we observed that in the group of patients with schistosomiasis there were higher levels of IL-10 and lower levels of IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and TNF compared to cultures from patients with leishmaniasis. Data from our group showed that cultured PBMCs from leishmaniasis patients after being stimulated with Schistosoma mansoni antigens were able to increase IL-10 production and decrease TNF and IFN-γ production (Bafica et al., 2011). IL-10 derived from DCs may limit Th1 expansion through the inhibition of IL-12 itself (Corinti et al., 2001) or through its ability to stimulate IL-10 production from T cells (McGuirk et al., 2002), thus reducing the pro-duction of TNF and IFN-γ. It is known that helminth infection induces IL-10 that is capable of modulating the immune response. However, a coinfection study by Yoshida et al. (1999) showed that infection of mice by S. mansoni did not affect the course of L. major infection. Cells from lymph nodes of these animals continued to produce IFN-γ, which is important for macrophage activation and elimination of intracellular parasites (Yoshida et al., 1999).

A higher frequency of L. braziliensis-infected MoDCs was observed in cultures of 72 h from patients with schistosomiasis compared to patients with leishmaniasis. There was no difference between the two groups of patients regarding the frequency of infected MoDCs after 2 h, 24 h, or 48 h nor in the number of Leishmania braziliensis amastigotes in 100 MoDCs evaluated at different times. Upon being stimulated with IFN-γ, macrophages isolated from S. mansoni-infected mice failed to eliminate L. major after infection in vitro (La Flamme et al., 2002). Despite the influence of helminth infection on the course of leishmaniasis, it has been observed in humans that early antihelminthic treatment neither improves the outcome of the lesion nor decreases the healing time of these lesions (Newlove et al., 2011).

Due to the regulation observed in dendritic cells infected by L. braziliensis and in lymphocytes of patients with schistosomiasis, this study suggests that coinfection may worsen clinical outcomes of leishmaniasis by preventing the induction of an effector Th1 response against the protozoan.

5. Conclusion

The MoDCs of individuals with schistosomiasis are more susceptible to L. braziliensis infection, possibly because they have a lower degree of activation and present a regulatory profile.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients of Corte de Pedra and Conde for participating in the study as well as all the teams of professionals who work in these endemic areas for their dedication to the clinical work of the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the CNPq/MST/INCT-DT, grant number 465229/2014-0 and National Institutes of Health, grant number: U01 AI136032.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Participants in this study do not present any conflicts of interest.

References

- Actor JK, Shirai M, Kullberg MC, Buller RM, Sher A, Berzofsky JA, 1993. Helminth infection results in decreased virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell and Th1 cytokine responses as well as delayed virus clearance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 90, 948–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal S, Agrawal A, Doughty B, Gerwitz A, Blenis J, Van Dyke T, Pulendran B, 2003. Cutting edge: different Toll-like receptor agonists instruct dendritic cells to induce distinct Th responses via differential modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos. J. Immunol 171, 4984–4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen M, 2010. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: advances in disease pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapeutics. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 35, 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli LR, Dutra WO, Almeida RP, Bacellar O, Carvalho EM, Gollob KJ, 2005. Activated inflammatory T cells correlate with lesion size in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Immunol. Lett 101, 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo MI, Hoppe B, Medeiros M Jr., Alcantara L, Almeida MC, Schriefer A, Oliveira RR, Kruschewsky R, Figueiredo JP, Cruz AA, Carvalho EM, 2004a. Impaired T helper 2 response to aeroallergen in helminth-infected patients with asthma. J. Infect. Dis 190, 1797–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo MI, Hoppe BS, Medeiros M Jr., Carvalho EM, 2004b. Schistosoma mansoni infection modulates the immune response against allergic and auto-immune diseases. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 99, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeredo-Coutinho RB, Pimentel MI, Zanini GM, Madeira MF, Cataldo JI, Schubach AO, Quintella LP, de Mello CX, Mendonça SC, 2016. Intestinal helminth coinfection is associated with mucosal lesions and poor response to therapy in American tegumentary leishmaniasis. Acta Trop 154, 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci A, Montagnoli C, Perruccio K, Bozza S, Gaziano R, Pitzurra L, Velardi A, d’Ostiani CF, Cutler JE, Romani L, 2002. Dendritic cells pulsed with fungal RNA induce protective immunity to Candida albicans in hematopoietic transplantation. J. Immunol 168, 2904–2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafica AM, Cardoso LS, Oliveira SC, Loukas A, Varela GT, Oliveira RR, Bacellar O, Carvalho EM, Araujo MI, 2011. Schistosoma mansoni antigens alter the cytokine response in vitro during cutaneous leishmaniasis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 106, 856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafica AM, Cardoso LS, Oliveira SC, Loukas A, Goes A, Oliveira RR, Carvalho EM, Araujo MI, 2012. Changes in T-cell and monocyte phenotypes In vitro by schistosoma mansoni antigens in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. J. Parasitol. Res 2012, 520308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baratta-Masini A, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Malaquias LC, Mayrink W, Martins-Filho OA, Correa-Oliveira R, 2007. Mixed cytokine profile during active cutaneous leishmaniasis and in natural resistance. Front. Biosci 12, 839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral-Netto M, Barral A, Brownell CE, Skeiky YA, Ellingsworth LR, Twardzik DR, Reed SG, 1992. Transforming growth factor-beta in leishmanial infection: a parasite escape mechanism. Science 257, 545–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR, 1998. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature 393, 478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth AE, Dunne DW, Fulford AJ, Ouma JH, Sturrock RF1, 1996. Immunity and morbidity in Schistosoma mansoni infection: quantitative aspects. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 55, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho EM, Barral A, Costa JM, Bittencourt A, Marsden P, 1994. Clinical and immunopathological aspects of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis. Acta Trop 56, 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho LP, Pearce EJ, Scott P, 2008. Functional dichotomy of dendritic cells following interaction with Leishmania braziliensis: infected cells produce high levels of TNF-alpha, whereas bystander dendritic cells are activated to promote T cell responses. J. Immunol 181, 6473–6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehmann K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, Alber G, 1996. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of in-terleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J. Exp. Med 184, 747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A, Tonks P, Jones FM, O’Shea H, Hutchings P, Fulford AJ, Dunne DW, 1999. Infection with Schistosoma mansoni prevents insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in non-obese diabetic mice. Parasite Immunol 21, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corinti S, Albanesi C, la Sala A, Pastore S, Girolomoni G, 2001. Regulatory activity of autocrine IL-10 on dendritic cell functions. J. Immunol 166, 4312–4318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da-Cruz AM, Bittar R, Mattos M, Oliveira-Neto MP, Nogueira R, Pinho-Ribeiro V, Azeredo-Coutinho RB, Coutinho SG, 2002. T-cell-mediated immune responses in patients with cutaneous or mucosal leishmaniasis: long-term evaluation after therapy. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol 9, 251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne DW, Cooke A, 2005. A worm’s eye view of the immune system: consequences for evolution of human autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol 5, 420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DE, Summers RW, Weinstock JV, 2007. Helminths as governors of immune-mediated inflammation. Int. J. Parasitol 37, 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrefaei M, El-Sheikh N, Kamal K, Cao H, 2003. HCV-specific CD27- CD28-memory T cells are depleted in hepatitis C virus and Schistosoma mansoni co-infection. Immunology 110, 513–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts B, Adegnika AA, Kruize YC, Smits HH, Kremsner PG, Yazdanbakhsh M, 2010. Functional impairment of human myeloid dendritic cells during Schistosoma haematobium infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 4, e667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez HJ, Sharpe AH, Stadecker MJ, 1999. Experimental murine schistosomiasis in the absence of B7 costimulatory molecules: reversal of elicited T cell cy-tokine profile and partial inhibition of egg granuloma formation. J. Immunol 162, 2884–2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Caspar P, Sher A, 2004. Parasite-induced Th2 polarization is associated with down-regulated dendritic cell responsiveness to Th1 stimuli and a transient delay in T lymphocyte cycling. J. Immunol 173, 2419–2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayeka-Wandabwa C, Kutima H, Nyambati VC, Ingonga J, Oyoo-Okoth E, Karani L, Jumba B, Githuku K, Anjili CO, 2013. Combination therapy using Pentostam and Praziquantel improves lesion healing and parasite resolution in BALB/c mice co-infected with Leishmania major and Schistosoma mansoni. Parasit Vector 6, 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CL, Medhat A, Malhotra I, Nafeh M, Helmy A, Khaudary J, Ibrahim S, El-Sherbiny M, Zaky S, Stupi RJ, Brustoski K, Shehata M, Shata MT, 1996. Cytokine control of parasite-specific anergy in human urinary schistosomiasis: IL-10 modulates lymphocyte reactivity. J. Immunol 156, 4715–4721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Flamme AC, Scott P, Pearce EJ, 2002. Schistosomiasis delays lesion resolution during Leishmania major infection by impairing parasite killing by macrophages. Parasite Immunol 24, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima LM, Santos SB, Oliveira RR, Cardoso LS, Oliveira SC, Goes AM, Loukas A, Carvalho EM, Araujo MI, 2013. Schistosoma antigens downmodulate the in vitro inflammatory response in individuals infected with human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1. Neuroimmunomodulation 20, 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes DM, Fernandes JS, Cardoso TM, Bafica AM, Oliveira SC, Carvalho EM, Araujo MI, Cardoso LS, 2014. Dendritic cell profile induced by Schistosoma mansoni antigen in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. BioMed Res. Int 743069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louzir H, 1998. Immunologic determinants of disease evolution in localized cutaneous leishmaniasis due to leishmania major. J. Infect. Dis 177, 1687–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AS, Straw AD, Bauman B, Pearce EJ, 2001. CD8-dendritic cell activation status plays an integral role in influencing Th2 response development. J. Immunol 167, 1982–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AS, Patton EA, La Flamme AC, Araujo MI, Huxtable CR, Bauman B, Pearce EJ1, 2002a. Impaired Th2 development and increased mortality during Schistosoma mansoni infection in the absence of CD40/CD154 interaction. J. Immunol 168, 4643–4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AS, Straw AD, Dalton NM, Pearce EJ, 2002b. Cutting edge: Th2 re-sponse induction by dendritic cells: a role for CD40. J. Immunol 168, 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marple A, Wu W, Shah S, Zhao Y, Du P, Gause WC, Yap GS, 2017. Cutting edge: helminth coinfection blocks effector differentiation of CD8T cells through alternate host Th2- and IL-10-Mediated responses. J. Immunol 198, 634–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos GI, Covas Cde J, Bittar Rde C, Gomes-Silva A, Marques F, Maniero VC, Amato VS, Oliveira-Neto MP, Mattos Mda S, Pirmez C, Sampaio EP, Moraes MO, Da-Cruz AM, 2007. IFNG +874T/A polymorphism is not associated with American tegumentary leishmaniasis susceptibility but can influence Leishmania induced IFN-gamma production. BMC Infect. Dis 7, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirk P, McCann C, Mills KH, 2002. Pathogen-specific T regulatory 1 cells induced in the respiratory tract by a bacterial molecule that stimulates interleukin 10 production by dendritic cells: a novel strategy for evasion of protective T helper type 1 responses by Bordetella pertussis. J. Exp. Med 195, 221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AS, Dzierszinski F, Boes M, Roos DS, Pearce EJ, 2004. Functional in-activation of immature dendritic cells by the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol 173, 2632–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros M Jr., Figueiredo JP, Almeida MC, Matos MA, Araujo MI, Cruz AA, Atta AM, Rego MA, de Jesus AR, Taketomi EA, Carvalho EM, 2003. Schistosoma mansoni infection is associated with a reduced course of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 111, 947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Murphy KM, 2000. Dendritic cell regulation of TH1-TH2 development. Nat. Immunol 1, 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nausch N, Louis D, Lantz O, Peguillet I, Trottein F, Chen IY, Appleby LJ, Bourke CD, Midzi N, Mduluza T, Mutapi F, 2012. Age-related patterns in human myeloid dendritic cell populations in people exposed to Schistosoma haematobium infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 6, e1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlove, Guimaraes LH, Alcântara L, Glesby MJ, Carvalho EM, Machado PR, 2011. Antihelminthic therapy and antimony in cutaneous leishmaniasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients co-infected with helminths and Leishmania braziliensis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 84, 551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal SE, Guimaraes LH, Machado PR, Alcantara L, Morgan DJ, Passos S, Glesby MJ, Carvalho EM, 2007. Influence of helminth infections on the clinical course of and immune response to Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis 195, 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS, 2002. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2, 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EJ, Caspar P, Grzych JM, Lewis FA, Sher A, 1991. Downregulation of Th1 cytokine production accompanies induction of Th2 responses by a parasitic helminth, Schistosoma mansoni. J. Exp. Med 173, 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto AF, Santos SB, Muniz AL, Basilio V, Rodrigues W Jr., Neva FA, Dutra WO, Gollob KJ, Jacobson S, Carvalho EM, 2005. Helminthic infection down-regulates type 1 immune responses in human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) carriers and is more prevalent in HTLV-1 carriers than in patients with HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. J. Infect. Dis 191, 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis EA, Azevedo TM, McBride AJ, Harn DA Jr., Reis MG, 2007. Naive donor responses to Schistosoma mansoni soluble egg antigens. Scand. J. Immunol 66, 662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-de-Jesus A, Almeida RP, Lessa H, Bacellar O, Carvalho EM, 1998. Cytokine profile and pathology in human leishmaniasis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 31, 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P, 1998. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature 393, 474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MT, 2005. Current understandings on the immunology of leishmaniasis and recent developments in prevention and treatment. Br. Med. Bull 75–76, 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutitzky LI, Ozkaynak E, Rottman JB, Stadecker MJ, 2003. Disruption of the ICOS-B7RP-1 costimulatory pathway leads to enhanced hepatic immunopathology and increased gamma interferon production by CD4T cells in murine schistosomiasis. Infect. Immun 71, 4040–4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin EA, Araujo MI, Carvalho EM, Pearce EJ, 1996. Impairment of tetanus toxoid-specific Th1-like immune responses in humans infected with Schistosoma mansoni. J. Infect. Dis 173, 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straw AD, MacDonald AS, Denkers EY, Pearce EJ, 2003. CD154 plays a central role in regulating dendritic cell activation during infections that induce Th1 or Th2 responses. J. Immunol 170, 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian G, Kazura JW, Pearlman E, Jia X, Malhotra I, King CL, 1997. B7–2 requirement for helminth-induced granuloma formation and CD4 type 2T helper cell cytokine expression. J. Immunol 158, 5914–5920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suciu-Foca N, Manavalan JS, Scotto L, Kim-Schulze S, Galluzzo S, Naiyer AJ, Fan J, Vlad G, Cortesini R, 2005. Molecular characterization of allospecific T suppressor and tolerogenic dendritic cells: review. Int. Immunopharmacol 5, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XJ, Li R, Sun X, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Liu XJ, Lu Q, Zhou CL, Wu ZD, 2012. Unique roles of Schistosoma japonicum protein Sj16 to induce IFN-gamma and IL-10 producing CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo. Parasite Immunol 34, 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MD, LeGoff L, Harris A, Malone E, Allen JE, Maizels RM, 2005. Removal of regulatory T cell activity reverses hyporesponsiveness and leads to filarial parasite clearance in vivo. J. Immunol 174, 4924–4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottein F, Pavelka N, Vizzardelli C, Angeli V, Zouain CS, Pelizzola M, Capozzoli M, Urbano M, Capron M, Belardelli F, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, 2004. A type I IFN-dependent pathway induced by Schistosoma mansoni eggs in mouse myeloid dendritic cells generates an inflammatory signature. J. Immunol 172, 3011–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vouldoukis I, Becherel PA, Riveros-Moreno V, Arock M, da Silva O, Debre P, Mazier D, Mossalayi MD, 1997. Interleukin-10 and interleukin-4 inhibit in-tracellular killing of Leishmania infantum and Leishmania major by human macro-phages by decreasing nitric oxide generation. Eur. J. Immunol 27, 860–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ML, Cao YM, Luo EJ, Zhang Y, Guo YJ, 2013. Pre-existing Schistosoma japonicum infection alters the immune response to Plasmodium berghei infection in C57BL/6 mice. Malar. J 12, 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S, Iyoda T, Tarbell K, Olson K, Velinzon K, Inaba K, Steinman RM, 2003. Direct expansion of functional CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells by antigen-processing dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med 198, 235–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yole Dorcas S., Shamala KT, Kithome Kiio, Gicheru Michael M., 2007. Studies on the interaction of Schistosoma mansoni and Leishmania major in experimentally infected Balb/c mice. Afr. J. Health Sci 14. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Maruyama H, Yabu Y, Amano T, Kobayakawa T, Ohta N, 1999. Immune response against protozoal and nematodal infection in mice with underlying Schistosoma mansoni infection. Parasitol. Int 48, 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone P, Fehervari Z, Jones FM, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Dunne DW, Cooke A, 2003. Schistosoma mansoni antigens modulate the activity of the innate immune response and prevent onset of type 1 diabetes. Eur. J. Immunol 33, 1439–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Ostiani CF, Del Sero G, Bacci A, Montagnoli C, Spreca A, Mencacci A, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Romani L1, 2000. Dendritic cells discriminate between yeasts and hyphae of the fungus Candida albicans. Implications for initiation of T helper cell immunity in vitro and in vivo. J. Exp. Med 191, 1661–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saint-Vis B, Fugier-Vivier I, Massacrier C, Gaillard C, Vanbervliet B, Ait-Yahia S, Banchereau J, Liu YJ, Lebecque S, Caux C, 1998. The cytokine profile ex-pressed by human dendritic cells is dependent on cell subtype and mode of activation. J. Immunol 160, 1666–1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]