Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the ability of the ratios of central venous to arterial carbon dioxide content and tension to arteriovenous oxygen content to predict an increase in oxygen consumption (VO2) upon fluid challenge (FC).

Methods and results

110 patients admitted to cardiothoracic ICU and in whom the physician had decided to perform an FC (with 500 ml of Ringer's lactate solution) were included. The arterial pressure, cardiac index (Ci), and arterial and venous blood gas levels were measured before and after FC. VO2 and CO2-O2 derived variables were calculated. VO2 responders were defined as patients showing more than a 15% increase in VO2. Of the 92 FC responders, 43 (46%) were VO2 responders. At baseline, pCO2 gap, C(a-v)O2 were lower in VO2 responders than in VO2 non-responders, and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) was higher in VO2 responders. FC was associated with an increase in MAP, SV, and CI in both groups. With regard to ScvO2, FC was associated with an increase in VO2 non-responders and a decrease in VO2 responders. FC was associated with a decrease in pvCO2 and pCO2 gap in VO2 non-responders only. The pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and C(a-v)CO2 content /C(a-v)O2 content ratio did not change with FC. The CO2 gap content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content /C(a-v)O2 content ratio did not predict fluid-induced VO2 changes (area under the curve (AUC) [95% confidence interval (CI)] = 0.52 [0.39‒0.64] and 0.53 [0.4–0.65], respectively; p = 0.757 and 0.71, respectively). ScvO2 predicted an increase of more than 15% in the VO2 (AUC [95%CI] = 0.67 [0.55‒0.78]; p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Our results showed that the ratios of central venous to arterial carbon dioxide content and tension to arteriovenous oxygen content were not predictive of VO2 changes following fluid challenge in postoperative cardiac surgery patients.

Introduction

Fluid challenge (FC) is the most frequently performed bedside haemodynamic intervention in perioperative care. This procedure is usually used to increase cardiac output (CO) so that oxygen delivery (DO2) matches oxygen consumption (VO2) [1, 2]. After FC, VO2 can either increase (if there is an oxygen debt) or remain unchanged [2]. In recent years, several studies have focused on parameters that are able to accurately track VO2/DO2 dependency [3–7]. Although the blood lactate concentration was initially described as a surrogate marker of VO2/DO2 dependency, an elevated lactate value may not necessarily reflect anaerobic metabolism [8]. Although ScvO2 might be indicative of DO2, its significance may be diminished during distributive shock with alteration of the oxygen extraction ratio (O2ER)—even after cardiac surgery [5, 9, 10]. It was recently suggested that the veno-arterial carbon dioxide tension gradient (pCO2 gap) and the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio are more sensitive indices of anaerobic metabolism and the VO2 increase upon FC [5, 11–14]. These parameters were developed and validated in ICU patients with sepsis, in whom they accurately predict an increase in VO2 with FC.

In clinical practice, the difficulty is to identify hemodynamic and/or oxygenation parameters that are clinically relevant to become endpoints for titration of interventions. Increasing DO2 is an accepted goal for optimization following cardiac surgery [15, 16] which is considered as a major surgery associated with high incidence of postoperative complications. Thus, predicting VO2 responsiveness can identify the patients for which DO2 increase is most beneficial [15, 16]. To date, these parameters have not been extensively studied in non-septic or post-operative patients. A few studies of postoperative cardiac surgery patients have shown that in contrary to the situation in patients with sepsis, pCO2 gap is poorly correlated with perfusion variables [17, 18].

The present study aims at investigating the ability of the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio to predict a VO2 increase upon FC in postoperative cardiac surgery patients.

Material and methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the independent ethics committee at Amiens University Hospital (Amiens, France). Because the protocol study is considered as observational and part of routine clinical practice, the French law did not require written consent. According to ethics committee, all patients received written information on the study. Oral consent was obtained from patient or subject’s next of kin. The capacity to consent was checked by excluding confusion in awake patient who were not sedated. Confusion was assessed by clinical examination based on confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit. In case of confusion, the consent was obtained from subject’s of kin. The consent was noted on study observation book. The present manuscript was drafted in compliance with the STROBE checklist for cohort studies [19].

Patients

This observational study was performed in the cardiothoracic ICU at Amiens University Hospital (Amiens, France) between 2014 and 2017. Some of the patients were previously included in a study that evaluate association between end tidal carbon dioxide pressure and oxygen extraction [7]. The main inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18 or over, controlled positive ventilation, and a clinical decision to perform FC for volume expansion. The indications for FC were arterial hypotension (a systolic arterial pressure (SAP) below 90 mmHg and/or a mean arterial pressure (MAP) below 65 mmHg), a stroke volume (SV) variation of more than 10% during a passive leg raising manoeuver and/or clinical signs of hypoperfusion (skin mottling, and a capillary refill time of more than 3 sec). The non-inclusion criteria were permanent arrhythmia, heart conduction block, a pacemaker, poor echogenicity, aortic regurgitation, spontaneous ventilation, ongoing haemorrhage, and right heart dysfunction.

Haemodynamic parameters

Transthoracic echocardiography (with the CX50 ultrasound system and an S5-1 Sector Array Transducer, Philips Medical System, Suresnes, France) was performed by a physician who was blinded to the study outcomes. The left ventricular ejection fraction was measured using Simpson’s biplane method with a four-chamber view. The aortic surface area (SAo, in cm2) was calculated as π×(diameter of the left ventricular outflow tract)2/4. The aortic velocity-time integral (VTIAo), was measured with pulsed Doppler at the LVOT on a five-chamber view. The SV (mL) was calculated as VTIAo×SAo. Cardiac output (CO) was calculated as SV×heart rate (HR) (ml min-1) and was expressed as an indexed CI, i.e. CO/body surface area (ml min-1 m2). Mean echocardiographic parameters were calculated from five measurements (regardless of the respiratory cycle) and analysed off lines.

Oxygenation parameters

We recorded the ventilator settings (tidal volume, plateau pressure and end-expiratory pressure) at baseline. All blood gas parameters were measured with arterial and central venous catheters. Arterial and venous blood gas levels, the blood lactate level, the blood haemoglobin (Hb) concentration and oxyhaemoglobin saturation were measured using an automated analyser (ABL800 FLEX, Radiometer, Bronshoj, Denmark). Arterial oxygen content (CaO2) and venous oxygen content (CvO2) were calculated as follows: CaO2 = 1.34 x Hb x SaO2 + 0.003 x PaO2; CvO2 = 1.34 x Hb x ScvO2 + 0.003 x PvO2, where Hb is the haemoglobin concentration (g.dl-1), PaO2 is the arterial oxygen pressure (mmHg), SaO2 is the arterial oxygen saturation (%), PvO2 is the venous oxygen pressure (mmHg), ScvO2 is the central venous oxygen saturation (in%), and 0.003 is the solubility coefficient of oxygen [14]. pCO2 gap was calculated as follows: pCO2 gap = PcvCO2 –PaCO2 (mmHg). C(a-v)O2 was calculated as CaO2 minus CvO2 (ml) [14]. DO2 and VO2 were calculated from arterial and central venous blood gas measurements as follows: DO2 (ml min-1 m-2) = (CaO2 x 10 x CO)/body surface area; VO2 (ml min-1 m-2) = the arteriovenous difference in oxygen content (C(a-v)O2 x CO x 10)/body surface area. Arterial and venous CO2 contents (CaCO2, CvCO2) were calculated according to the Douglas formula [14, 20]. The C(a-v)CO2 content was calculated as CvCO2 minus CaCO2 (ml).

Protocol

During the study period, the patients were mechanically ventilated in volume-controlled mode, with a tidal volume set to 7–9 ml kg-1 ideal body weight, and a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5–8 cmH2O. The patients were sedated with propofol, with a target Ramsay score >5. The ventilator settings (oxygen inspired fraction, tidal volume, respiratory rate, and end positive pressure) were not modified during the study period.

The following clinical parameters were recorded: age, gender, weight, ventilation parameters, and primary diagnosis. After an equilibration period, HR, SAP, MAP, diastolic arterial pressure, central venous pressure (CVP), SV, CO, and arterial/venous blood gas levels were measured at baseline. In the present study, FC always consisted of a 10-minute infusion of 500 ml of Ringer's lactate solution. Immediately after FC, a second set of measurements was made.

Statistical analysis

The variables' distribution was assessed using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were expressed as the number, proportion (in percent), mean ± standard deviation (SD) or the median [interquartile range (IQR)], as appropriate. Patients were classified as fluid responders or non-responders as a function of the effect of FC on the SV. An FC response was defined as an increase of more than 15% in the SV after FC [21]. Patients were classified as VO2 responders or non-responders as a function of the effect of FC on VO2. A VO2 response was defined as an increase of more than 15% in the VO2 after FC [7]. The non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test, Student’s paired t test, Student’s t test, and the Mann-Whitney test were used to assess statistical significance, as appropriate. Linear correlations were tested using Pearson's or Spearman's rank method. A receiver-operating characteristic curve was used to establish the ability of ScvO2, pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio or the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio to predict an increase of more than 15% in VO2 [7, 14]. Assuming that 60% of patients would be fluid responders and that 20 to 30% of fluid responders would be VO2 responders, we calculated that a sample of 105 patients was sufficient to demonstrate that the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio predict an increase in VO2 upon FC with an area under the curve (AUC) greater than 0.80, a power of 80%, and an alpha risk of 0.05. Taking the exclusion criteria and incomplete data in account, the sample size was set to 115 participants. The threshold for statistical significance was set to p<0.05. SPSS software (version 24, IBM, New York, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patients

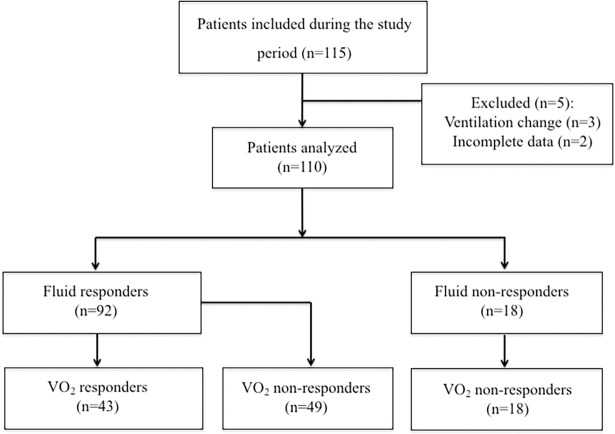

All patients had undergone cardiovascular surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass Table 1, Fig 1. Of the 115 included patients, five were excluded (Fig 1), and so the final analysis covered 110 patients. Of these, 92 (84%) were classified as FC responders, and 43 (47%) were classified as VO2 responders.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants on inclusion.

| Variables | Overall population (n = 110) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD), years) | 69 (11) |

| Gender (F/M) | 32 /78 |

| Surgery, n (%) | |

| Valvular | 55 (50) |

| CABG | 30 (27) |

| Combined surgery | 15 (14) |

| Other | 6 (9) |

| SAPS 2 | 40 (13) |

| Respiratory parameters | |

| Tidal volume (ml kg-1 of predicted body weight, mean (SD), | 7.8 (0.6) |

| Total PEEP (cmH2O, mean (SD)) | 6 (1) |

| Number of patients treated with norepinephrine (n, %) | 25 (25) |

| Median dose (gamma Kg-1 min-1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.4) |

| Number of patients treated with dobutamine (n, %) | 4 (5) |

| Median dose (gamma Kg-1 min-1) | 5 (5 to 7) |

| LVEF (%, mean (SD)) | 49 (11) |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD or the number (%). CABG: coronary artery bypass graft.

Fig 1. Flow chart diagram of the study.

Effect of FC on haemodynamic and oxygenation parameters in the population as a whole

FC was associated with increases in MAP, CVP, SV, CO, DO2, and VO2, and decreases in HR, and pCO2 gap Table 2. At baseline, the arterial lactate concentration was not correlated with ScvO2 (r = -0.044, p = 0.650), pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio (r = 0.052, p = 0.587), or C(a-v)CO2 content /C(a-v)O2 content ratio (r = 0.019, p = 0.841).

Table 2. Comparison of haemodynamic parameters according to response of VO2.

| Hemodynamic variables | VO2 responders (n = 43) |

VO2 non responders (n = 49) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory minute ventilation (l min-1) | 8.2 (1.3) | 8 (1) | 0.290 |

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.3 (1.7) | 36.6 (0.4) | 0.273 |

| Capillary refill time (sec) | |||

| Pre-FC | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.3) | 0.908 |

| Post-FC | 3.2 (1.2) a | 2.9 (1.4) a | 0.289 |

| Haemoglobin (g dl-1) | |||

| Pre-FC | 11.4 (1.6) | 11.2 (1.4) | 0.518 |

| Post-FC | 11.2 (1.7) a | 10.8 (1.4) a | 0.210 |

| HR (bpm) | |||

| Pre-FC | 82 (22) | 85 (19) | 0.574 |

| Post-FC | 78 (21) a | 81 (16) a | 0.404 |

| MAP (mmHg) | |||

| Pre-FC | 74 (14) | 70 (12) | 0.140 |

| Post-FC | 84 (16) a | 82 (12) a | 0.472 |

| SV (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 44 (15) | 42 (15) | 0.652 |

| Post-FC | 60 (18) a | 55 (21) a | 0.263 |

| CI (ml min-1 m-2) | |||

| Pre-FC | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.7) | 0.524 |

| Post-FC | 2.3 (0.7) a | 2.2 (0.9) a | 0.921 |

| DO2 (ml min-1 m-2) | |||

| Pre-FC | 269 (103) | 274 (95) | 0.811 |

| Post-FC | 339 (124) a | 319 (119) a | 0.428 |

| VO2 (ml min-1 m-2) | |||

| Pre-FC | 75 (34) | 100 (39) | 0.002 |

| Post-FC | 115 (37) a | 93 (31) | 0.007 |

Values are expressed as the mean (SD) or the median [interquartile range]. CI, indexed cardiac output; DO2, oxygen delivery; FC, fluid challenge; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SV, stroke volume; VO2, oxygen consumption

a: p<0.05 within groups (pre-/post-FC).

Differences between VO2 responders and VO2 non-responders among fluid responders

Of the 92 FC responders, 43 (46%) were VO2 responders (Fig 1). All VO2 responders were FC responders Table 2. FC increased MAP, SV, and CI in the two groups Table 2.

At baseline, pCO2 gap and C(a-v)O2 were lower in VO2 responders than in VO2 non-responders, and ScvO2 was higher Table 3. The arterial lactate concentration did not differ when comparing the two groups, and did not change upon FC. Furthermore, FC increased ScvO2 in VO2 non-responders and decreased ScvO2 in VO2 responders. FC decreased pvCO2 and pCO2 gap in VO2 non-responders only Table 3. The pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio did not change upon FC.

Table 3. Comparison of perfusion parameters according to response of VO2.

| Variables | VO2 responders (n = 43) |

VO2 non responders (n = 49) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial pH | |||

| Pre-FC | 7.35 (0.07) | 7.38 (0.2) | 0.447 |

| Post-FC | 7.38 (0.05) a | 7.39 (0.2) | 0.667 |

| Venous pH | |||

| Pre-FC | 7.32 (0.05) | 7.33 (0.2) | 0.751 |

| Post-FC | 7.32 (0.06) | 7.33 (0.2) | 0.728 |

| Oxygen arterial saturation (%) | |||

| Pre-FC | 97.6 (1.2) | 97.7 (1.7) | 0.679 |

| Post-FC | 97.4 (1.7) | 97.6 (1.4) | 0.628 |

| ScvO2 (%) | |||

| Pre-FC | 67.7 (12) | 60.8 (10) | 0.003 |

| Post-FC | 62.8 (9) a | 68.4 (10) a | 0.005 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | |||

| Pre-FC | 38.4 (5) | 36.4 (5) | 0.068 |

| Post-FC | 37.3 (4) | 36.7 (5) | 0.510 |

| PvCO2 (mmHg) | |||

| Pre-FC | 46.7 (6.1) | 46.6 (5.4) | 0.942 |

| Post-FC | 46.5 (5.4) | 44.7 (5.3) a | 0.104 |

| pCO2 gap (mmHg) | |||

| Pre-FC | 8.3 (3.7) | 10 (3.3) | 0.020 |

| Post-FC | 9.2 (3.8) | 8 (3.6) a | 0.143 |

| CaO2 (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 15.4 (2.2) | 15.1 (2) | 0.555 |

| Post-FC | 15 (2.2) a | 14.4 (1.9) a | 0.171 |

| CvO2 (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 10.8 (2.7) | 9.5 (2.1) | 0.009 |

| Post-FC | 9.7 (2.2) a | 10.2 (2.2) a | 0.285 |

| C(a-v)O2 (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 4.5 (1.8) | 5.6 (1.6) | 0.003 |

| Post-FC | 5.3 (1.2) a | 4.2 (1.9) a | 0.002 |

| CaCO2 (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 51.2 (7) | 48.3 (7.9) | 0.034 |

| Post-FC | 52.1 (5.9) | 49.8 (5.1) a | 0.052 |

| CvCO2 (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 57.3 (5.8) | 55.6 (5.4) | 0.052 |

| Post-FC | 56.9 (6.3) | 53.2 (5.9) a | 0.004 |

| C(a-v)CO2 content (ml) | |||

| Pre-FC | 5.8 (2.9–7.4) | 6.8 (4.5–7.4) | 0.239 |

| Post-FC | 5.3 (3.5–7.3) | 2.9 (1.6–6.1) a | 0.023 |

| pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 (mmHg ml-1) | |||

| Pre-FC | 1.93 (1.36–2.29) | 1.89 (1.42–2.) | 0.710 |

| Post-FC | 1.82 (1.39–2.21) | 1.86 (1.36–2.29) a | 0.863 |

| C(a-v)CO2 content /C(a-v)O2 content ratio | |||

| Pre-FC | 0.98 (0.43–2.06) | 1.1 (0.86–1.85) | 0.625 |

| Post-FC | 0.96 (0.59–1.39) | 0.81 (0.46–1.15) a | 0.109 |

| Arterial lactates (mmol l-1) | |||

| Pre-FC | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.9 (0.7) | 0.590 |

| Post-FC | 1.8 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0.251 |

Values are expressed as the mean (SD) or the median [interquartile range]. FC, fluid challenge; VO2, oxygen consumption

a: p<0.05 within groups (pre-/post-FC).

The FC-induced changes in the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio and the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio were associated (r = 0.499, p<0.0001), but neither was correlated with changes in VO2 (r = -0.092, p = 0.337 and r = -0.05, p = 0.957) or arterial lactates (r = 0.129, p = 0.18 and r = -0.10, p = 0.916). The FC-induced changes in VO2 and ScvO2 were associated (r = 0.61, p = 0.0001).

Ability of overall perfusion parameters to predict an increase in VO2

With an AUC [95% confidence interval (CI)] of 0.52 [0.39‒0.64] and 0.53 [0.4–0.65], respectively; p = 0.757 and 0.71, respectively, the C(a-v)CO2 content /C(a-v)O2 content ratio and the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio did not predict FC-associated changes in VO2. Baseline ScvO2 was poorly predictive of an increase of more than 15% in the VO2, with an AUC [95%CI] of 0.67 [0.55‒0.78] (p<0.0001).

Discussion

Our study produced several relevant results. The pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content /C(a-v)O2 content ratio did not predict increase in VO2 in postoperative cardiac surgery patients. ScvO2 was poorly predictive of an FC-associated increase in VO2. The arterial lactate level was not associated with VO2 changes. These results suggest that physician should take in account the population studied before analysing oxygen derivate parameters and predicting VO2 dependency.

The pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio are known to be associated with anaerobic metabolism, lactate clearance, and mortality in ICU patients with sepsis [11, 12, 14]. The present study is the first to have specifically focused on postoperative patients. Our present results did not suggest that the above-mentioned ratios are of value in non-septic patients. There are several possible explanations for our findings. Most of these are probably related to the difference between the various study populations (i.e. sepsis vs cardiac surgery), which may alter the significance of and relationships between systemic parameters related to oxygen and carbon dioxide [9, 22].

In the present study, the relationship between FC and changes in arterial and venous carbon dioxide content/tension differed to that observed in patients with sepsis [6, 12, 14]. Baseline pCO2 gap was higher after cardiac surgery in VO2 non-responders, and decreased only in VO2 non-responders. In the context of sepsis, pCO2 gap is higher in VO2 responder patients, and decreases only in VO2 responder patients. We did not demonstrate differences in FC-induced changes in O2-derived parameters, relative to those observed in patients with sepsis. C(a-v)O2 decreased in VO2 non-responders (due to an increase in CvO2) and increased in VO2 responders (due to a decrease in CvO2). The physiological relationships that allow the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio to be used as indicators of anaerobic metabolism are probably altered by the inability of pCO2 gap to adequately reflect tissue CO2 production and elimination [17]. Our group has already studied pCO2 gap as a prognostic factor for the postoperative course in cardiac surgery [17]. Even though pCO2 gap was poorly correlated with tissue perfusion parameters, we did not demonstrate an association between pCO2 gap and outcomes.

The divergence between sepsis and post-operative situations might be due to several factors. The extent of microcirculation alterations caused by sepsis or surgery/cardiopulmonary bypass may differ [23, 24]. It has been demonstrated that sepsis is systematically associated with the disruption of microcirculatory regulation, i.e. a decrease in the functional capillary index, absent/intermittent capillary flow, increased heterogeneity in the perfusion index, arteriovenous shunting, and cellular hypoxia [25]. Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with a wide range of microcirculatory alterations, including a decrease in microvascular perfusion, increased heterogeneity in the perfusion index and red blood cell velocity, and arteriovenous shunting [23, 26]. These changes are associated with alterations in the arteriovenous oxygen difference, systemic oxygen consumption, and CO2 and O2 diffusion [27]. Moreover, cardiac surgery microcirculatory alterations may be induced by (amongst other factors) cardiopulmonary bypass haemodilution and temperature changes during the operative period. Haemodilution was demonstrated to alter the relationship between CO2 pressures and CO2 contents, which do not alter pCO2 gap in the same way as haemorrhage [28]. It was also demonstrated that anaesthetic agents alter regional critical DO2 and microcirculation by changing the peripheral vascular resistance [29]. When considering the above-mentioned arguments and data as a whole, the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and the C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v) O2 content ratio do not reflect complex, inconsistent alterations in regional VO2, DO2 and the latter’s interrelationships after cardiac surgery.

Our results confirmed those report by Fischer et al., who demonstrated that only ScvO2 was associated with VO2 dependency in postoperative patients after maximization of the SV by FC [30]. Nevertheless, ScvO2 remains poorly predictive of VO2 changes [10]. Our results and those of Fischer et al. confirm previous demonstrations of ScvO2’s poor ability to track VO2 changes [10]. Likewise, arterial lactate was not associated with VO2 changes in Fischer et al.’s study and in the present study. Arterial lactate is known to be a complex variable that may be not always be associated with tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion and anaerobic metabolism [8]. At present, no clinical parameter has demonstrated its superiority to predict VO2 dependency. Only goal directed hemodynamic optimisation protocols have demonstrated a decrease of post-operative complications due to a maximisation of DO2. Further research is needed to identify and describe new indicators of VO2 dependency in non-septic patients. In this way, ventriculo-arterial coupling and mitochondrial PO2 may be of interest [31, 32].

The present studies had several limitations. The fact that pCO2 gap was measured in central venous blood (rather than mixed venous blood) might have underestimated CO2 exchange from splanchnic territories. However, other studies have used central venous blood to calculate VO2- and CO2-derived parameters [14]. The observed changes in O2- and CO2-derived parameter were small and reproducible [33]. We assessed VO2 using the Fick method, which may not be reliable in ICU patients. Nevertheless, previous studies have used the Fick method to calculate VO2 [6, 14]. The latter results were similar to those previously demonstrated to be predictive of VO2 changes. Lastly, we performed a single-centre study; however, our results are in line with those reported in Fischer et al.’s study [28].

Conclusions

Our present results did not demonstrate the ability of the pCO2 gap/C(a-v)O2 ratio and C(a-v)CO2 content/C(a-v)O2 content ratio to predict VO2 dependency in postoperative cardiac surgery patients. The present finding demonstrated that the population studied should be consider at bedside when assessing VO2 dependency with oxygen derivate parameters. The effect of cardiac surgery and/or cardiopulmonary bypass on the relationship between CO2 content and CO2 partial pressure may explain in part this finding.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper. Raw data are available after notification and authorization of the competent authorities. In France, all computer data (including databases, in Cover Letter particular patient data) are protected by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL), the national data protection authority for France. CNIL is an independent French administrative regulatory body whose mission is to ensure that data privacy law is applied to the collection, storage, and use of personal data. As the database of this study was authorized by the CNIL, we cannot make available data without prior agreement of the CNIL. Requests may be sent to: elisabeth.laillet@chu-dijon.fr.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Schumacker PT, Cain SM. The concept of a critical oxygen delivery. Intensive Care Med 1987;13:223–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Oxygen transport—the oxygen delivery controversy. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:1990–1996 10.1007/s00134-004-2384-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronco JJ, Fenwick JC, Tweeddale MG, Wiggs BR, Phang PT, Cooper DJ, et al. Identification of the critical oxygen delivery for anaerobic metabolism in critically ill septic and non septic humans. JAMA 1993;270:1724–1730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker J, Coffernils M, Leon M, Gris P,Vincent JL. Blood lactate levels are superior to oxygen derived variables in predicting outcome in human septick shock. Chest 1991;99:856–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Oxygen uptake/oxygen supply dependency: fact or fiction? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 1995;10:229–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monnet X, Julien F, Ait-Hamou, Leguoy, Gosset C, Jozwiak M, et al. Lactate and venoarterial carbon dioxyde difference/arterial-venous oxygen difference ratio but not central venous oxygen saturation predict increase in oxygen consumption in fluid responders. Crit care med 2013;41:1412–1420 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318275cece [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guinot PG, Guilbart M, Hchikat AH, Trujillo M, Huette P, Bar S, et al. Association Between End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide Pressure and Cardiac Output During Fluid Expansion in Operative Patients Depend on the Change of Oxygen Extraction. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen LW. Lactate Elevation During and After Major Cardiac Surgery in Adults: A Review of Etiology, Prognostic Value, and Management. Anesth Analg 2017;125:743–752 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komatsu T, Shibutani K, Okamoto K, Kumar V, Kubal K, Sanchala V, et al. Critical level of oxygen delivery after cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit Care Med 1987;15:194–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Squara P. Central venous oxygenation: when physiology explains apparent discrepancies Critical Care 2014, 18:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesquida J, Saludes P, Gruartmoner G, Espinal C, Torrents E, Baigorri F, et al. Central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide difference combined with arterial-to-venous oxygen content difference is associated with lactate evolution in the hemodynamic resuscitation process in early septic shock. Crit Care 2015. March 28;19:126 10.1186/s13054-015-0858-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallat J, Pepy F, Lemyze M, Gasan G, Vangrunderbeeck N, Tronchon L, et al. Central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure difference in early resuscitation from septic shock: a prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2014;31:371–80 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ospina-Tascón GA, Umaña M, Bermúdez W, Bautista-Rincón DF, Hernandez G, Bruhn A, et al. Combination of arterial lactate levels and venous-arterial CO2 to arterial-venous O2 content difference ratio as markers of resuscitation in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:796–805 10.1007/s00134-015-3720-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallat J, Lemyze M, Meddour M, Pepy F, Gasan G, Barrailler S, et al. Ratios of central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide content or tension to arteriovenous oxygen content are better markers of global anaerobic metabolism than lactate in septic shock patients. Ann Intensive Care 2016;6:10 10.1186/s13613-016-0110-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osawa EA, Rhodes A, Landoni G, Galas FR, Fukushima JT, Park CH, et al. Effect of Perioperative GoalDirected Hemodynamic Resuscitation Therapy on OutcomesFollowing Cardiac Surgery:A Randomized Clinical Trial and Systematic Review. Crit Care Med 2016;44:724–33 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Backer D. Detailing the cardiovascular profile in shock patients. Critical care 2017;21:311 10.1186/s13054-017-1908-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guinot PG, Badoux L, Bernard E, Abou-Arab O, Lorne E, Dupont H. Central Venous-to-Arterial Carbon Dioxide Partial Pressure Difference in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery is Not Related to Postoperative Outcomes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:1190–1196 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morel J, Grand N, Axiotis G, Bouchet JB, Faure M, Auboyer C, et al. High veno-arterial carbon dioxide gradient is not predictive of worst outcome after an elective cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Monit Comput 2016;30:783–789 10.1007/s10877-016-9855-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douglas AR, Jones NL, Reed JW. Calculation of whole blood CO2 content. J Appl Physiol 1985;65:473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guinot P-G, Urbina B, de Broca B, Bernard E, Dupont H, Lorne E. Predictability of the respiratory variation of stroke volume varies according to the definition of fluid responsiveness. Br J Anaesth 2014;112:580–581 10.1093/bja/aeu031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf YG, Cotev S, Perel A, Manny J. Dependence of oxygen consumption on cardiac output in sepsis. Crit Care Med 1987. March;15(3):198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kara A, Akin S, Ince C. The response of the microcirculation to cardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anesthesiol 2016, 29:85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Backer D, Cortes DO, Donadello K, Vincent JL. Pathophysiology of microcirculatory dysfunction and the pathogenesis of septic shock. Virulence 2014; 5: 73–79 10.4161/viru.26482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edul VS, Enrico C, Laviolle B, Vazquez AR, Ince C, Dubin A. Quantitative assessment of the microcirculation in healthy volunteers and in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1443–8 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823dae59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atasever B, Boer C, Goedhart P, Biervliet J, Seyffert J, Speekenbrink R, et al. Distinct alterations in sublingual microcirculatory blood flow and hemoglobin oxygenation in on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011;25:784–90 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koning NJ, Simon LE, Asfar P, Baufreton C, Boer C. Systemic microvascular shunting through hyperdynamic capillaries after acute physiological disturbances following cardiopulmonary bypass. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014;307:H967–75 10.1152/ajpheart.00397.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubin A, Ferrara G, Kanoore Edul VS, Martins E, Canales HS, Canullán C, et al. Venoarterial PCO2-to-arteriovenous oxygen content difference ratio is a poor surrogate for anaerobic metabolism in hemodilution: an experimental study. Ann Intensive Care 2017;7:65 10.1186/s13613-017-0288-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Linden P, Gilbart E, Engelman E, Schmartz D, Vincent JL. Effects of anesthetic agents on systemic critical O2 delivery. Journal of Applied Physiology 1991;71:83–9 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer MO, Bonnet V, Lorne E, Lefrant JY, Rebet O, Courteille B, et al. ; French Hemodynamic Team. Assessment of macro- and micro-oxygenation parameters during fractional fluid infusion: A pilot study. J Crit Care 2017;40:91–98 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harms FA, Bodmer SI, Raat NJ, Mik EG. Non-invasive monitoring of mitochondrial oxygenation and respiration in critical illness using a novel technique. Crit Care 2015. 22;19:343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guinot PG, Longrois D, Kamel S, Lorne E, Dupont H. Ventriculo-arterial coupling analysis predicts the hemodynamic response to norepinephrine in hypotensive postoperative patients: a prospective observationnal study. Crit care med 2018;46:e17–e25 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mallat J, Lazkani A, Lemyze M, Pepy F, Meddour M, Gasan G, et al. Repeatability of blood gas parameters, PCO2 gap, and PCO2 gap to arterial-to-venous oxygen content difference in critically ill adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper. Raw data are available after notification and authorization of the competent authorities. In France, all computer data (including databases, in Cover Letter particular patient data) are protected by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL), the national data protection authority for France. CNIL is an independent French administrative regulatory body whose mission is to ensure that data privacy law is applied to the collection, storage, and use of personal data. As the database of this study was authorized by the CNIL, we cannot make available data without prior agreement of the CNIL. Requests may be sent to: elisabeth.laillet@chu-dijon.fr.