Abstract

Cold atmospheric-pressure plasma (CAP) is a relatively new method used for bacterial inactivation. CAP is ionized gas that can be generated by applying an electric current to air or a feeding gas. It contains reactive species and emits UV radiation, which have antibacterial activity. Previous data suggests that CAP is effective in microbial inactivation and can decontaminate and sterilize surfaces, but its exact mode of action is still under debate. This study demonstrates the effect of CAP on the whole proteome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms, which is a dominant pathogen in cystic fibrosis and medical device-related infections. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to identify differentially regulated proteins of whole cell P. aeruginosa extracts. A total of 16 proteins were identified to be affected by plasma treatment compared to the control. Eight of the identified proteins have functions in transcription and translation and their expression changes are likely to be part of a general physiological response instead of a CAP-specific adaptation. However, CAP also affected bacterioferritin (Bfr), Isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh), Trigger factor (Tig) and a chemotaxis protein, which may be involved in P. aeruginosa’s specific response to CAP. We confirm that bacterioferritin B plays a role in the bacterial response to CAP because ΔbfrB mutants of both PAO1 and PA14 are more susceptible to plasma-induced cell-death than their corresponding wild-type strains. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing the effect of plasma on the whole proteome of a pathogenic microorganism. It will help our understanding of the mode of action of CAP-mediated bacterial inactivation and thus support a safe and effective routine use of CAP in clinical and industrial settings.

Introduction

Over the last century, the widespread use of antibiotics has quickly given rise to multi-drug resistant bacteria [1]. The Centre of Disease Control estimates 2 million people succumb each year to antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, resulting in 23,000 deaths, and has suggested inappropriate prescription and use of antibiotics are major contributors to the increase in resistance [2]. Frequent use of antibacterial treatments places bacteria under biological pressure, which results in genetic alterations that subsequently improve its survival against antibiotics.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen with an intrinsically high antibiotic resistance. Cystic fibrosis (CF) patients suffer from chronic bacterial pulmonary infections with P. aeruginosa as the predominant respiratory pathogen [3]. The recurring infections have been proven to be difficult to treat with current antibiotic regimens; this has been thought to be due to the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilms in the CF patient’s airways [3]. In addition to secretion of actin and extracellular DNA from the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), formation of biofilms in the airways produce an excess amount of mucous that coats the airway, creating a low oxygen environment ideal for enhanced bacterial growth [4].

Biofilm formation is a characteristic microbial development that was shown to increase antibiotic resistance in microorganisms [4, 5]. Biofilms are a group of microbial cells enclosed in a matrix of EPS that are attached to a surface [4]. This specific structure serves to cement the whole biofilm community, instead of individual cells, to a surface [5]. It was demonstrated that biofilm cells show a higher resistance to antimicrobial methods due to a range of differences from their planktonic counterparts, including the presence of the EPS, oxidative stress response, differential gene or protein expression, and the presence of persister cells [6–8]. A higher resistance means that biofilm killing often needs longer treatment times than killing of planktonic cell cultures of the same species in a direct comparison [9–11].

Cold atmospheric-pressure plasma (CAP) has been investigated for its anti-bacterial, -fungal and -viral properties in in vitro models [11–13]. CAP is partially ionized gas created by applying high voltage electricity to a gas at atmospheric pressure. The electrons are at high temperature, while the heavy species (molecules, atoms and ions) remain close to room temperature. CAP contains reactive species including excited molecules radicals and ions, and emits UV radiation [14, 15]. Depending on operating conditions and the choice of gas, a mixture of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) is produced that has antibacterial effects. Some studies have included high oxygen content gases in combination with atmospheric oxygen and nitrogen species, which introduces a higher diversity of RONS e.g. hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nitric oxide (NO) and peroxinitrate (O2NOO-) [14–16]. Along with the above plasma components, electrons and neutral atoms target cellular and metabolic processes in microorganisms that can cause oxidative stress resulting in cell damage [17, 18]. Bacteria have developed several mechanisms of regulating oxidative stress to increase cell survival under these conditions. This includes the increased expression of P. aeruginosa MexXY-OprM multidrug efflux system, which is commonly associated with aminoglycoside resistance in cystic fibrosis isolates, following increased peroxide exposure [19, 20].

Several CAP studies have been conducted on well-known human pathogens such as P. aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and several Staphylococcus spp. Application of plasma to bacterial cells has proven effective in microbial inactivation, decontamination and sterilization of surfaces and wound healing [11, 21–23]. However, only limited data regarding the mechanism of CAP-induced cell death is available and in particular the effects on bacterial genomes and/or proteomes remain to be elucidated.

In this study, we investigated the effect of CAP treatment on the proteome of P. aeruginosa biofilm cells. We identified 16 differentially regulated proteins following CAP treatment using LC-MS/MS. Eight proteins involved in ribosomal machinery were found to be upregulated following plasma treatment. Interestingly, bacterioferritin Bfr was also highly expressed after 3 min plasma exposure. Further studies into the role of Bfr in biofilm survival upon CAP treatment showed that a Δbfr transposon mutant strain was more susceptible to CAP treatment than its wild-type counterpart, suggesting a role for ferritin in CAP-induced cell death, possibly due to oxidative stress.

Experimental procedure

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PW6979 BfrB-C04:: ISlacZ/hah were obtained from PAO1 transposon mutant library [24] and strains P. aeruginosa PA14 wildtype and ΔbfrB mutant were obtained from http://pa14.mgh.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/pa14/home.cgi [25].

Bacteria were cultivated on nutrient agar (1g l-1 `Lab-Lemco’ powder, 2g l-1 170 yeast extract, 5g l-1 peptone, 5g l-1 sodium chloride, 15g l-1 agar, pH 7.4; Oxoid) using standard methods. Overnight cultures were inoculated into 10 ml nutrient broth and incubated at 37°C with 150 rpm shaking.

Biofilm formation

Biofilms were grown in a Centre for Disease Control Biofilm Reactor (CBR, Biosurface Technologies, Bozeman, MT, USA) according to the standard protocol [26]. Briefly, bacteria were inoculated with 10 ml of overnight culture in tryptic soya broth (20g l-1 ‘Tryptic Soya Broth’ powder; Oxoid; TSB) grown at 37°C in a shaking incubator. Samples were grown on stainless steel coupons in a bioreactor containing 500 ml of TSB (600 mg l-1), the bioreactor was then switched to continuous-flow (11.7 ml min-1) with fresh TSB (100 mg l-1) media once cells had attached to the coupons. After overnight growth, the coupons were aseptically removed from the encasing rods and placed into 24-well plates. Coupons were rinsed twice with 1 ml phosphate buffer saline (PBS) solution to remove non-adhered cells.

Cold atmospheric-pressure plasma (CAP) treatment

Plasma treatment was performed using the kINPen med (Neoplas tools GmbH, INP Greifswald, Germany) as previously described [11]. Briefly, coupons were placed 1 cm away from the plasma and the kINPen was operated with argon at 3.2 slm. Plasma treatment was conducted in triplicates for two time-points, 3 or 10 min, respectively. As a control, coupons were treated with non-ionized argon gas for 10 min at 2.8 slm; the plasma does not ignite for flow rates below 3.0 slm.

After treatment, coupons were submerged in 1 ml PBS solution to rehydrate surviving cells. Biofilms were scraped from the coupon surface using a flat-edge spatula. In addition, coupons and all liquids were sonicated for 5 min to dissolve possible cell clumps and encourage remaining biofilm to detach from coupon surface. The removal of cells from coupons was confirmed by microscopy and plate count (data not shown).

Preparation of whole cell samples

Samples derived from plasma-treated biofilms were processed at the Bioanalytical Mass Spectrometry Facility (BMSF) at the University of New South Wales. Biofilm samples for LC-MS/MS were stored as pellets pooled from 24 coupons. Samples were centrifuged in an Eppendorf MiniSpin centrifuge (12,000 × g, 3 min). The cell pellets were washed once in PBS and then frozen at -20°C. Cells were lysed using 40 μl of 2% sodium dooxycholate (SDC), 1 μl 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1 μl protease inhibitor (MMSAFE) followed by 30 min of sonication (Unisonics). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation in an Eppendorf MiniSpin centrifuge (12,100 x g, 5 min) and the supernatant discarded.

Quantification and in-solution digestion of proteins

The protein concentration in the lysates was measured using a 2-D quantification kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (GE Healthcare Life Science). Briefly, proteins were incubated at 37°C in reduction (1 μl 5mM DTT) and alkaline (2 μl 5mM iodoacetamide) buffers for 15 and 20 min, respectively. Residue SDC was removed by the addition of 10 μl 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 5 μl Millipore water and further extracted using 2.5 μl 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and centrifuged in an Eppendorf MiniSpin centrifuge (12,100 × g, 10 min). Finally, the peptides were desalted and concentrated using a StageTipsTM C18 microcolumn according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Two-point-five μl of reconstituted, digested peptides were separated by nanoLC using an Ultimate nanoRSLC UPLC and autosampler system (Dionex, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Peptides were eluted using a linear gradient of H2O:CH3CN (98:2 volume, 0.1% formic acid) to H2O:CH3CN (64:36 volume, 0.1% formic acid) at 500 nl min-1 over 30 min. High voltage (2000 V) was applied to a low-volume titanium union (Valco) with the column oven heated to 45°C (Sonation, Biberach, Germany) and the tip positioned ~0.5 cm from the heated capillary (T = 300°C) of a QExactive Plus (Thermo Electron, Bremen, Germany) Mass Spectrometer. Positive ions were generated by electrospray and the QExactive operated in data-dependent acquisition mode. A survey scan of mass-to-charge ratio 350–1750 was acquired (resolution = 70,000 at m/z 200, with an accumulation target value of 1,000,000 ions) and lockmass enabled (m/z 445.12003). Up to the 10 most abundant ions (> 80,000 counts, underfill ratio 10%) with charge states > +2 and < +7 were sequentially isolated (width m/z 2.5) and fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation (normalized collision energy = 30) with an automatic gain control target of 100,000 ions (resolution = 17,500 at m/z 200). M/z ratios selected for MS/MS were dynamically excluded for 30 seconds.

Initial data validation and analysis

Peak lists were generated using Mascot Daemon/Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science, London, England) using default parameters, and submitted to the database search program Mascot (version 2.5.1, Matrix Science). Search parameters: precursor tolerance 4 parts per million (ppm) and product ion tolerances ± 0.05 Da; Met(O) carboxyamidomethyl-Cys specified as variable modification, enzyme specificity was trypsin, 1 missed cleavage was possible and the non-redundant protein Pseudomonas database from NCBI (Jan 2015) searched. Peptide and protein identifications generated from the peaks were validating using Scaffold (version 4.6.1, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR). Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability using the Scaffold delta-mass correction. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99.0% probability and contained at least 2 identified peptides. Statistical analysis of proteins detected at each plasma time point was completed using the t-test (p < 0.1) in addition to significance in fold-change to compare changes in protein levels across samples. Functional information proteins of significance were gathered from the Pseudomonas Genome Database [27]. The basic alignment search tool (BLAST) was used to search for sequence similarities to hypothetical or unknown proteins using UniProt accession numbers and protein sequences database [28]. Protein–protein interaction networks were built using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING, v10) with a medium confidence level (0.4) and all available predication methods [29].

CAP treatment of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 ΔbfrB mutants

To further investigate upregulation of bacterioferritin following CAP treatment, the susceptibility to plasma treatment of PAO1 and PA14 wild-type strains and their respective ΔbfrB mutants was measured to examine potential differences between strains. Biofilms were allowed to form on stainless steel coupons placed in 24 well plates with nutrient broth for 48 h. Coupons were aseptically removed and washed twice with PBS before plasma treatment was performed and cells removed from the coupon as described above. Cells were serial diluted in PBS and plated onto nutrient agar. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C before counting colony forming units.

Results and discussion

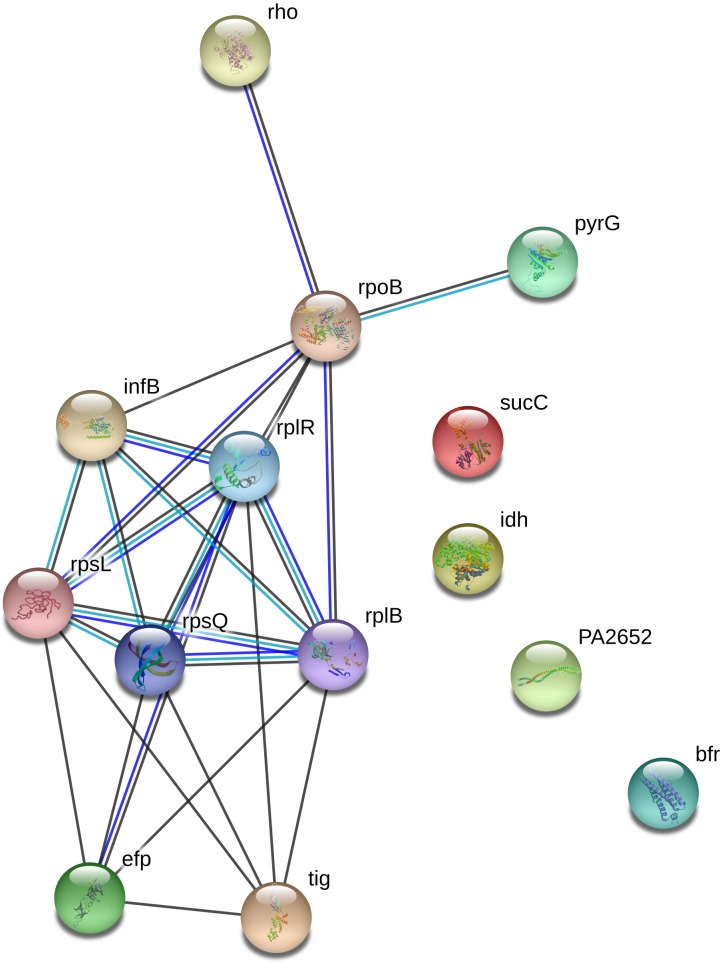

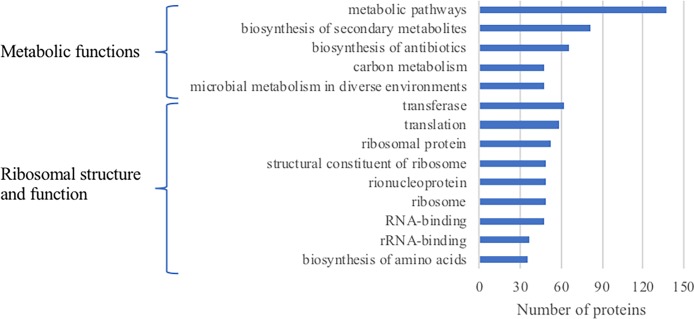

From Scaffold, a total of 16 proteins were identified to be of significance (p > 0.1) in total spectrum counts and fold change between plasma treatment duration (Table 1). Eight out of 16 of the identified proteins have functions in transcription and translation, including RplR, RplB, RpsL, Rho, Efp, RpsQ, RpoB and InfB. Two of the identified proteins (SucC, Idh) are involved in the energy metabolism of the cell, one protein is a chemotaxis protein and one protein (PyrG) is important for nucleotide biosynthesis. Interestingly, two proteins, trigger factor (Tig) and bacterioferritin (BfrB), are important for adaptation and protection of the cell. STRING was used to identify protein–protein interaction networks present in plasma-treated samples, as depicted in Fig 1. The protein interaction networks indicated extensive connections between proteins that were associated with genomic and metabolic processes, and in the removal of reactive species. Additionally, a functional annotation analysis using Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID v6.8) was also conducted (Fig 2) on all proteins identified (S1 Table). This shows that out of 317 identified proteins, 137 (42%) have roles in metabolic pathways. A table listing all 317 proteins identified from the LC-MS/MS data is provided in the supplementary material (S1 Table).

Table 1. Proteins found to be upregulated following plasma treatment; p < 0.1.

| Gene no. | Gene name | Function | Fold-change | Localization | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control vs 10 min CAP treatment | ||||||

| PA0859 | AruC/ArgD | N2-Succinylornithine 5-aminotransferase (SOAT) = N2-acetylornithine 5-Aminotransferase (ACOAT) | >4.3 | Unknown | Hypothetical | |

| PA4247 | RplR | 50S ribosomal protein L18 | 7.3 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

| PA4260 | RplB | 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 5.3 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

| PA4268 | RpsL | 30S ribosomal protein S12 | >4.3 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

| PA5239 | Rho | Transcription termination factor Rho | 2.6 | Cytoplasmic membrane, | Transcription, RNA processing & degradation | |

| Control vs 3 min CAP treatment | ||||||

| PA1588 | SucC | Succinyl-CoA synthetase beta chain | 6.5 | Cytoplasmic | Energy metabolism | |

| PA1800 | Tig | Trigger factor | >4.67 | Cytoplasmic, Outer Membrane Vesicle | Cell division, chaperones & heat shock | |

| PA2624 | Idh | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | >4.67 | Unknown (multiple localization sites) | Energy metabolism | |

| PA2652 | - | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 5.9 | Cytoplasmic Membrane | Chemotaxis | |

| PA2851 | Efp | Translation elongation factor P | >7.5 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

| PA3531 | Bfr | Bacterioferritin | >3.3 | Cytoplasmic, Outer Membrane Vesicle | Adaptation, protection, transport of small molecules | |

| PA3637 | PyrG | CTP synthase | >4 | Cytoplasmic | Nucleotide biosynthesis and metabolism | |

| PA4254 | RpsQ | 30S ribosomal protein S17 | >5.3 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

| PA4260 | RplB | 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 11 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

| PA4270 | RpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase beta chain | 3.5 | Cytoplasmic, Outer Membrane Vesicle | Transcription, RNA processing & degradation | |

| PA4744 | InfB | Translation initiation factor IF-2 | >7.7 | Cytoplasmic | Translation, post-translational modification, degradation | |

Fig 1. Protein interactions for unique and significantly increased proteins in plasma-treated P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Interactions were detected by STRING (29). Lines indicate known or predicted protein–protein interactions. Black lines indicate proteins that are co-expressed, green lines indicate proteins within the same gene neighbourhood, blue lines indicate proteins that may be functionally linked based on gene co-occurrence. These networks show the interactions between proteins associated with metabolic processing.

Fig 2. Functional annotation by DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 of proteins upregulated in plasma-treated biofilm samples.

Functional groups are listed if the proteins they contain exceed 10% of total number of identified proteins.

The highest number of proteins that were found to be upregulated after plasma treatment are involved in transcription and translation processes and are ribosomal proteins (Table 1). Changes in the expression level of these proteins are unlikely to be a specific response to CAP. Instead, the changes could be a reflection of general metabolic shift and changes in cell physiology due to stress. Additionally, the very high abundance of ribosomal proteins in the bacterial cell making a significant change in expression levels more likely due to higher change of random variations occurring for larger samples.

Two of the proteins upregulated after CAP treatment are succinyl-CoA synthetase (SucC) and isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh). Both proteins have functions in the energy metabolism in the cell. Changes in expression of proteins that are involved in energy metabolism have been observed as a response to antibiotic stress, in particular when a subpopulation of cells become persister cells [30]. In P. aeruginosa, SucC, as part of the sucCD operon, preferentially synthesizes ATP and GTP, but is also capable of generating UTP or CTP. It was shown that the resulting GTP can serve as an alternative source for alginate, an important exopolysaccharide for biofilm formation, as well as for the synthesis of other macromolecules requiring GTP such as RNA and protein [31]. It could be speculated that changes in energy metabolism protein levels after CAP treatment may indicate a response of the cell to ensure survival of a subpopulation of cells.

Interestingly, two of the upregulated proteins can be categorized as having adaptation and protection functionality. One of the proteins is trigger factor (Tig). The Tig protein, is together with DnaK, involved in folding of newly synthesized proteins, and it has been shown that cells without Tig and DnaK are not viable above 30°C [32]. The other protein is bacterioferritin (BfrB). The possible involvement in protection from CAP-induced oxidative stress regulation is discussed below.

Bacterioferritin is upregulated after CAP treatment

Bacterioferritin B (BfrB) was highly upregulated after CAP treatment (Table 1). This family of proteins has functions in adaptation, protection or transport of small molecules. Bacterioferritins are important for the regulation of the intracellular iron concentration and were shown to play a role in regulating an oxidative stress response via the iron metabolism.

In prokaryotes, iron is an important cofactor of many enzymatic reactions necessary for survival. Soluble iron (Fe2+) is moderately required for respiration but, due to incomplete O2 reduction under aerobic conditions, it produces a range of toxic reactive oxygen species [33, 34]. Ferritins and bacterioferritins (Bfr) are iron storage proteins that P. aeruginosa procures to store iron and regulate intracellular iron concentration. In P. aeruginosa, two different types of bacterioferritin exist: bacterioferritin-A (with α-subunit) and bacterioferritin-B (with a β-subunit) [35]. These molecules oxidize Fe2+ into Fe3+. The iron is stored in the form of ferrihydrite or ferric phosphate, depending on the presence of phosphate, and released under iron-limiting conditions. P. aeruginosa also makes use of DNA-binding proteins that protect the chromosome from iron-induced hydroxyl damage [36]. Bacterioferritins consists of a ferroxidase centre made up of histidine and glutamine acids that binds and oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+, which is then stored in the central cavity. Superoxides have been observed to mobilize the stored iron to its reactive Fe2+ state and cause oxidative damage. Other reports suggest that hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions may activate the iron regulator protein [37].

In murine models, cells treated with RONs-producing drugs have shown a 6-fold increase in ferritin production and cells exposed to iron-containing substances, e.g. haemin, were able to reduce cytotoxic responses to high doses of hydrogen peroxide [37]. Orino et al. showed that increased synthesis of ferritin occurs in HeLa cells exposed to oxidative stress and that an overexpression of ferritin reduced the accumulation of ROS in response to oxidant challenge [37]. These reports suggest the role of ferritin as a protection against reactive species. The oxidative stress response in bacteria is coordinated with iron homeostasis, as reviewed by [38]. In P. aeruginosa biofilms, the importance of exogenous iron plays a significant role in biofilm formation. This is shown by the use of the mammalian iron chelator lactoferritin, which induced continuous twitching motility and a reduced biofilm thickness [39].

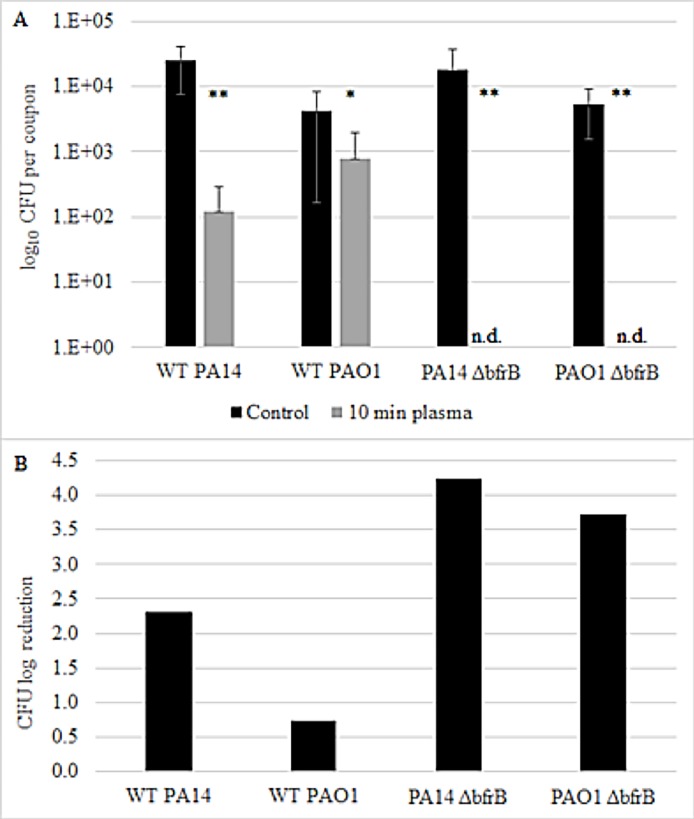

To show whether bacterioferritin plays a role in the bacterial response to cold plasma treatment, we investigated two P. aeruginosa strains (PAO1 and PA14) and their corresponding ΔbfrB mutants for survival after CAP treatment (Fig 3). We hypothesized that if the resulting oxidative stress from plasma treatment leads to an increase in ferritins as a protection, mutations in ferritin genes may result in lower survival of the strains upon CAP treatment. Indeed, our results show that both P. aeruginosa wild-type strains have a higher survival rate after 10 min CAP treatment compared to the ΔbfrB mutants (Fig 3). CAP treatment only led to a small (0.74) log reduction in CFU numbers in P. aeruginosa PAO1 wild-type (from 4.24 x 103 CFU control to 7.78 x 102 after plasma treatment) and 2.31 log reduction in P. aeruginosa PA14 wild-type, respectively (from 24.33 x 103 CFU control to 1.2 x 102 after plasma treatment). In contrast, for both P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 ΔbfrB mutants, 10 min CAP treatment completely eliminated the biofilms with no viable cells detected after treatment (Fig 3B). These results suggest that BfrB has a protective effect for the cells against CAP-induced oxidative damage in P. aeruginosa.

Fig 3. Effect of CAP treatment on cell numbers of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 wild-types and corresponding ΔbfrB mutants.

(A) Number of log10 CFU recovered from biofilm coupons of control (black bar) and after 10 min CAP treatment (grey bar) for all four strains; n. d. = not detected. Values represent average of three coupons per treatment and error bars show the standard deviation. Data is shown as significant with either p < 0.05 (95% confidence, *) or p < 0.01 (99% confidence, **), based on a Student’s t-test (2 tailed, homoscedastic). (B) CFU log reduction after 10 min CAP for all four strains.

Lack of functional bacterioferritins in P. aeruginosa will reduce the microorganism’s ability to provide iron required for respiration. In addition, the ability to regulate intracellular iron concentrations would be reduced in ΔbfrB mutants compared to the wild-type with fully functional bacterioferritin genes. Thus, it is likely that the higher cell death in the bfrB mutants may be due to the synergistic effects of the CAP-induced oxidative stress and the toxic compounds derived from reactive Fe2+.

Conclusions

Biofilms are increasingly being recognized by the public health community as an important determinant in persistent chronic microbial infections. Additionally, biofilms can be problematic for many industries by fouling surfaces and contaminating food. CAP has the potential to eliminate biofilms that are resistant to conventional antimicrobial methods in a fast and reliable way. Our results show that the mode of action of CAP is linked to oxidative stress regulation in P. aeruginosa. We identified bacterioferritin B as one of the proteins affected by CAP and further results suggest that BfrB gives protection to P. aeruginosa upon CAP exposure. This is consistent with observations of the role of bacterioferritins in the response to oxidative stress of other organisms Identifying the mode of action of CAP in treating bacteria is an important step towards the routine use of CAP in industry and healthcare settings.

Supporting information

Proteins identified are recognised based on number of unique peptides detected across 3 biological replicates (Rep.1, Rep. 2, Rep. 3) each from 3 different treatment conditions: 10 min gas treatment, 3 min plasma treatment and 10 min plasma treatment. Percentage of average sequence coverage refers to the percentage of all the amino acids in the protein sequence that were covered by identified peptides detected in the sample. Proteins identified to be of significance (p > 0.1) in total spectrum count and fold change based upon 10 min gas treatment vs. 10 min plasma treatment and 10 min gas treatment vs. 3 min plasma treatment are presented in Table 1.

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was partially funded by a CSIRO OCE postdoctoral fellowship to AM-P. The specific roles of this author are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Penesyan A, Gillings M, Paulsen I. Antibiotic Discovery: Combatting Bacterial Resistance in Cells and in Biofilm Communities. Molecules. 2015;20(4):5286–98. 10.3390/molecules20045286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frieden T. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Centre of Disease Control; 2013. Report No.: CS239559-B.

- 3.Shawar RM, MacLeod DL, Garber RL, Burns JL, Stapp JR, Clausen CR, et al. Activities of tobramycin and six other antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(12):2877–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bales PM, Renke EM, May SL, Shen Y, Nelson DC. Purification and Characterization of Biofilm-Associated EPS Exopolysaccharides from ESKAPE Organisms and Other Pathogens. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e67950–e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice SA, Tan CH, Mikkelsen PJ, Kung V, Woo J, Tay M, et al. The biofilm life cycle and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are dependent on a filamentous prophage. ISME J. 2009;3(3):271–82. 10.1038/ismej.2008.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4):999–1007. 10.1128/AAC.45.4.999-1007.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35(4):322–32. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seneviratne CJ, Wang Y, Jin L, Wong SS, Herath TD, Samaranayake LP. Unraveling the resistance of microbial biofilms: has proteomics been helpful? Proteomics. 2012;12(4–5):651–65. 10.1002/pmic.201100356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joaquin JC, Kwan C, Abramzon N, Vandervoort K, Brelles-Mariño G. Is gas-discharge plasma a new solution to the old problem of biofilm inactivation? Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 3):724–32. 10.1099/mic.0.021501-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahid IK, Ha S-D. The Paradox of Mixed-Species Biofilms in the Context of Food Safety. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2014;13(5):990–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mai-Prochnow A, Bradbury M, Ostrikov K, Murphy AB. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Response and Resistance to Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Is Linked to the Redox-Active Molecule Phenazine. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0130373–e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Liang Y, Wei K, Li W, Yao M, Zhang J, et al. MS2 Virus Inactivation by Atmospheric-Pressure Cold Plasma Using Different Gas Carriers and Power Levels. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2015;81(3):996–1002. 10.1128/AEM.03322-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itooka K, Takahashi K, Izawa S. Fluorescence microscopic analysis of antifungal effects of cold atmospheric pressure plasma in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100(21):9295–304. 10.1007/s00253-016-7783-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weltmann KD, Kindel E, Brandenburg R, Meyer C, Bussiahn R, Wilke C, et al. Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet for Medical Therapy: Plasma Parameters and Risk Estimation. Contributions to Plasma Physics. 2009;49(9):631–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laroussi M, Leipold F. Evaluation of the roles of reactive species, heat, and UV radiation in the inactivation of bacterial cells by air plasmas at atmospheric pressure. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2004;233(1–3):81–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frein D, Schildknecht S, Bachschmid M, Ullrich V. Redox regulation: A new challenge for pharmacology. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;70(6):811–23. 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi SG, Cooper M, Yost A, Paff M, Ercan UK, Fridman G, et al. Nonthermal Dielectric-Barrier Discharge Plasma-Induced Inactivation Involves Oxidative DNA Damage and Membrane Lipid Peroxidation in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(3):1053–62. 10.1128/AAC.01002-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabiscol E, Tamarit J, Ros J. Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. Int Microbiol. 2000;3(1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poole K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67(9):2069–89. 10.1093/jac/dks196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraud S, Poole K. Oxidative stress induction of the MexXY multidrug efflux genes and promotion of aminoglycoside resistance development in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(3):1068–74. 10.1128/AAC.01495-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ermolaeva SA, Varfolomeev AF, Chernukha MY, Yurov DS, Vasiliev MM, Kaminskaya AA, et al. Bactericidal effects of non-thermal argon plasma in vitro, in biofilms and in the animal model of infected wounds. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2011;60(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alkawareek MY, Algwari QT, Laverty G, Gorman SP, Graham WG, O'Connell D, et al. Eradication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms by Atmospheric Pressure Non-Thermal Plasma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e44289–e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zelaya AJ, Stough G, Rad N, Vandervoort K, Brelles-Mariño G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Inactivation: Decreased Cell Culturability, Adhesiveness to Surfaces, and Biofilm Thickness Upon High-Pressure Nonthermal Plasma Treatment. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 2010;38(12):3398–403. 10.1109/TPS.2010.2082570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(24):14339–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberati NT, Urbach JM, Miyata S, Lee DG, Drenkard E, Wu G, et al. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(8):2833–8. 10.1073/pnas.0511100103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goeres DM, Loetterle LR, Hamilton MA, Murga R, Kirby DW, Donlan RM. Statistical Assessment of a Laboratory Method for Growing Biofilms. Microbiology. 2005;151(3):757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winsor GL, Lam DK, Fleming L, Lo R, Whiteside MD, Yu NY, et al. Pseudomonas Genome Database: improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, et al. STRING 8—a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amato SM, Fazen CH, Henry TC, Mok WW, Orman MA, Sandvik EL, et al. The role of metabolism in bacterial persistence. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:70 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapatral V, Bina X, Chakrabarty AM. Succinyl Coenzyme A Synthetase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a Broad Specificity for Nucleoside Triphosphate (NTP) Synthesis Modulates Specificity for NTP Synthesis by the 12-Kilodalton Form of Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinase. Journal of Bacteriology. 2000;182(5):1333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bratlie MS, Johansen J, Drabløs F. Relationship between operon preference and functional properties of persistent genes in bacterial genomes. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wardman P, Candeias LP. Fenton chemistry: an introduction. Radiat Res. 1996;145(5):523–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haber F, Weiss J. The Catalytic Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide by Iron Salts. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 1934;147(861):332–51. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JL. The Physiological Role of Ferritin-Like Compounds in Bacteria. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2004;30(3):173–85. 10.1080/10408410490435151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberg ED. Iron and infection. Microbiol Rev. 1978;42(1):45–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orino K, Lehman L, Tsuji Y, Ayaki H, Torti SV, Torti FM. Ferritin and the response to oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2001;357(Pt 1):241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornelis P, Wei Q, Andrews SC, Vinckx T. Iron homeostasis and management of oxidative stress response in bacteria. Metallomics. 2011;3(6):540–9. 10.1039/c1mt00022e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh PK, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP, Welsh MJ. A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development. Nature. 2002;417(6888):552–5. 10.1038/417552a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proteins identified are recognised based on number of unique peptides detected across 3 biological replicates (Rep.1, Rep. 2, Rep. 3) each from 3 different treatment conditions: 10 min gas treatment, 3 min plasma treatment and 10 min plasma treatment. Percentage of average sequence coverage refers to the percentage of all the amino acids in the protein sequence that were covered by identified peptides detected in the sample. Proteins identified to be of significance (p > 0.1) in total spectrum count and fold change based upon 10 min gas treatment vs. 10 min plasma treatment and 10 min gas treatment vs. 3 min plasma treatment are presented in Table 1.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.